Abstract

Calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide were added to sugarcane juice to investigate their effect on color, pH, antioxidant activity, reducing sugar, acrylamide and HMF mitigation in dark brown sugar production. Results showed that the content of 52–67% acrylamide in the dark brown sugar was mitigated with 0.1–1.0% chitosan addition and the reducing power of dark brown sugar increased with 0.5–1.0% chitosan addition. Furthermore, the addition of 0.5–1.0% chitosan or chitooligosaccharide increased HMF formation. Only the pH of dark brown sugar with chitosan addition was lower than that of other dark brown sugars. This is due to the low pH condition in dark brown sugar mitigating Maillard reaction and acrylamide formation. When the pH of sugarcane juice with chitosan adjusted back to pH 7 again, the acrylamide content of dark brown sugars significant increased (p < 0.05). Acrylamide and HMF are both produced through the Maillard reaction, the lower pH will cause the hydrolysis of sucrose to produce more HMF and reducing sugar. The L values and white index of dark brown sugar with 0.5–1.0% added chitosan were lower than those of control dark brown sugar (p < 0.05). High negative correlation was observed between HMF and acrylamide in the present study.

Keywords: Dark brown sugar, Calcium citrate, Acrylamide, 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural, Chitooligosaccharide, Chitosan

Introduction

Dark brown sugar is a popular solidified form of sugar derived from sugar cane juice in Taiwan and many other countries (Asikin et al. 2016). Although it is not a major table sugar or snack, nor a major raw material for the production of confectionary, beverage and bakery products (Centre for Food Safety 2015), it is used as a form of souvenir candy or coffee/tea sweetener. Dark brown sugar is mainly composed of sucrose, glucose and fructose along with minor components such as proteins, insoluble solids, phenolics, minerals and natural asparagines, all of which contribute to it biological and nutritional values (Jaffe 2015). To make it, raw sugar cane juice is limed, clarified and repeatedly evaporated by open pan drying without removing the molasses components. Its brown appearance and flavor come from the Maillard reaction, caramelization and the phenolic compounds in sugar cane juice (Asikin et al. 2014). Acrylamide and 5-hydroxylmethylfurfural (HMF) also form during the process of concentrating the dark brown sugar (Centre for Food Safety 2015). Acrylamide is a cancinogenic neurotoxic compound formed in heat-processed starchy food products (Lineback et al. 2012). Tareke et al. (2000) proposed that food heated to a high temperature is the major source of acrylamide consumed by humans. Acrylamide from brown sugar contributes less than 1% of the total acrylamide intake of adults in Hong Kong (28 to 860 μg/kg; Centre for Food Safety 2015). The acrylamide content of baked and fried starchy foods can be in range of 150–4000 μg/kg (Tareke et al. 2000) and the development of effective ways to mitigate the formation of acrylamide in baked and fried snack foods is an urgent issue faced by the food industry. HMF, which is suspected to have mutagenic and genotoxic effects (Surh and Tannenbaum 1994), is also generated by the Maillard reaction or generated by caramelization of reducing sugars in heated foods (Quarta and Anese 2010). Dark brown sugar is becoming popular in the production of beverage and bakery products in Taiwan, and high acrylamide content has been found in some dark brown sugar used in food (Cheng et al. 2009).

Calcium is recognized for its ability to prevent osteoporosis, and the calcium ions in heated food products interfere with acrylamide formation (Acar et al. 2012). Therefore, fortifying dark brown sugar with calcium citrate might be expected to reduce the formation of acrylamide during the dark brown sugar process. Laboratory experiments have shown that low molecular weight chitosan (50–190 kDa) can be used to reduce the formation of acrylamide in a food model system (Chang et al. 2016; Sung et al. 2018), although this has not yet been tested at an industrial level.

Several practices have been claimed to inhibit acrylamide formation in heated foods: the addition of divalent cations, such as calcium salts (Gokmen and Senyuva 2007; Lindsay and Jang 2005); replacement of reducing sugars like glucose and fructose with non-reducing sugars like sucrose (Amrein et al. 2004; Gokmen et al. 2007a, b); substituting ammonium salts with baking powder (Biedermann and Grob 2003); adding acidulants to lower the pH of the food system (Jung et al. 2003); diluting asparagine by adding glycine (Brathen et al. 2005); and adding asparaginase to reduce free asparagine (Ciesarova et al. 2006; Pedreschi et al. 2008).

No reports exist concerning possible mitigating effects of chitooligosccharide on the formation of acrylamide and HMF, nor on its effects on the functional properties of the Maillard reaction and caramelization products generated from dark brown sugar. HMF, acrylamide content, pH, antioxidant activity and color change were compared between dark brown sugar made with sugarcane juice and test sugarcane juice with added calcium citrate, chitosans or chitooligosaccharide.

Materials and methods

Raw materials and chemicals

13C3-labelled acrylamide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Acrylamide standard (99.9%) was obtained from J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Acetonitrile and formic acid were supplied by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Oasis MCX (3 mL, 60 mg) and Oasis HLB (6 mL, 200 mg) solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridges were obtained from Waters (Milford, MA, USA). Chemical reagents used in this study were analytical grade.

Preparation of dark brown sugar

Sugarcane juice of the ROC 16 sugarcane cultivar (Saccharum officinarum) harvesting at maturity stage was obtained from the Research Center of Taiwan Sugar Corporation (Tainan, Taiwan) during the February 2017 harvesting period. The preparation process of dark brown sugar was followed the method of Takahashi et al. (2016) with some modification. The juices were adjusted to pH 7.5 ± 0.2 using Ca(OH)2 solution and centrifugation at 11827 g for 20 min. Calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide at 0.1%, 0.5% and 1.0% levels of sugarcane juice were added. The clarified juice was concentrated in a 130 °C oven until the sugar content of juice reached 50°Brix. The syrup was heated and stirred at 130 °C and 25 rpm using a magnetic stirrer (PC-420D, Corning, New York, USA). Then, it was heated at 140 °C with continuous stirring at 200 rpm. The semi-solid product was cooled down and kept in a desiccator for 48 h to facilitate drying and stored in a desiccator at room temperature until use. The pH of the dark brown sugar and sugar cane juice was measured by a pH meter (pH 510, Eutech Instruments Pte Ltd, Ayer Pajah Cresent, Singapore) that was standardized with solutions at pH 4.0 and 7.0 buffers by the method of Navarro and Morales (2017).

Assay for reducing sugars and asparagine content of dark brown sugar

Reducing sugars were quantitatively measured using a dinitrosalicylic acid-reducing sugar assay following the method of James (1995). Standard glucose solution (100–1000 μg/mL) and dark brown sugar (0.1 g) added to 5 mL of deionized, distilled were prepared in the assay for reducing sugars.

Free amino acids in dark brown sugar were extracted as described by Bartolomeo and Maisano (2006). Dark brown sugar (0.5 g) was weighted into a 50 mL centrifuge tube and 20 mL of 0.1 N HCl was added. The centrifuge tube was placed in an ultrasonic water bath for 10 min and topped up to 25 mL with 0.1 N HCl. The solution was filtered through filter paper. An aliquot (20 μL) of filtrate was transferred into a glass vial and 100 μL of 0.4 M borate buffer (pH 10.2) was added and shaken vigorously. An aliquot (20 μL) of the mixture was transferred into a glass vial and 100 μL of 0.4 M borate buffer (pH 10.2) was added and vortexed again. The mixture was transferred into a glass vial and 20 μL of o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) was added and vortexed for 60 s. Then, 20 μL of 9-fluroemenylmethyl chloroformate (FMOC-Cl) was added and vortexed for 30 s. The mixture was reconstituted with 1280 μL of deionized, distilled water and then samples were subjected to derivatization. Chromatographic separation was performed on a Capcell Pak C18 AQS5 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan) in accordance with the method of Bartolomeo and Maisano (2006) at 40 °C, with detection at λ = 338 nm. Mobile phase A was 40 mM NaH2PO4 adjusted to pH 7.8 with NaOH, while mobile phase B followed by a 5 min step that raised eluent B to 28% in a total analysis time of 15 min.

Chromaticity testing

Dark brown sugar color was examined using a spectrocolorimeter (TC-1800 MK II, Tokyo, Japan) measuring the L value (lightness), a value (redness/greenness) and b value (yellowness/blueness) following the method of Dinç et al. (2014). Both a black cup and a white tile were examined before the test to standardize the spectrocolorimeter. The colour of the dark brown sugar was recorded after taking three measurements for each sample and triplicate determinations were recorded for each treatment. Color difference ΔE was calculated using the following equation:

| 1 |

where ΔL = Lsample − Lcontrol; Δa = asample − acontrol; Δb = bsample − bcontrol. The brown index (BI) was calculated using the following equation:

| 2 |

where x = (a sample + 1.75 L sample)/(5.645Lsample + asample − 3.012bsample). The white index (WI) was calculated using the following equation:

| 3 |

Method for extracting and measuring acrylamide and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in dark brown sugar

Acrylamide extraction from dark brown sugar and was measured by the HPLC method according to the method of Chen et al. (2016). Dark brown sugar sample (1 g) was placed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Fifteen mL of deionized distilled water was added. The solution was mixed in a reciprocal shaker for 60 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 7741 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (3 mL) was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter. The MCX/HLB cartridge was conditioned with 3 mL and 5 mL of methanol followed by 3 mL and 5 mL of deionized distilled water, respectively. The filtrate (3.0 mL) was passed through the Oasis HLB/MCX cartridge to absorb acrylamide, and then it was discarded. The cartridge was washed with 3.5 mL of de-ionized distilled water; the first 0.5 mL of filtrate was discarded, while the remaining 3.0 mL of eluent was collected in an amber glass vial. The eluent was concentrated under vacuum for HPLC and MS analysis.

The HPLC system (D2000) consisted of an L-2130 pump, L-2400 detector, L-2300 column oven and an L-2200 autosampler (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Chromatographic separation was performed on a Capcell Pak C18 AQ S5 column (5 μm, 4.6 mm × 250 mm) (Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan) using 25 °C deionized distilled water at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min (mobile phase: 100% double distilled water; injection volume: 20 μL). The 400 μL sample was spiked with 100 μL of 13C3-labeled acrylamide with 0.5 mL of double distilled water. The acrylamide eluate (2 μL) of HPLC was injected into an MS detector (mobile phase: (1) 0.1% (v/v) formic acid/water; (2) 0.1% (v/v) formic acid/methanol; source temperature: 600 °C; electrospray capillary voltage: 5.5 kV; collision energy: 30 V). Data acquisition was performed using the selected ion monitoring mode. The ions monitored in the sample were m/z 72.04 for acrylamide and m/z 75.04 for 13C3-labeled acrylamide. Full scan analyses were performed in the mass range 50–200. The acrylamide calibration curve was built in the range of 250–50,000 ng/mL.

HMF levels of the dark brown sugar were also determined using the HPLC method (Oral et al. 2014). A 1 g sample was placed into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Nine mL of deionized distilled water and 1 mL of hexane was added. The solution was mixed in a reciprocal shaker for 60 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 1482 g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (3 mL) was filtered through a 0.45 μm nylon filter. The Oasis® HLB/MCX cartridge was conditioned with 5 mL and 3 mL of methanol followed by 5 mL and 3 mL of deionized distilled water, respectively. The filtrate (3.0 mL) was passed through the Oasis HLB/MCX cartridge to absorb HMF, and then it was discarded. The cartridge was washed with 3.5 mL of de-ionized distilled water; the first 0.5 mL of filtrate was discarded, while the remaining 3.0 mL of eluent was collected in an amber glass vial. The eluent was concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C (RV 10 digital, IKA, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany) for HPLC analysis.

The HPLC system (D2000) and column were mentioned as the acrylamide analysis and using 25 °C de-ionized, distilled water at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile. A 20 μL filtered concentrated eludate was injected by autosampler at 10 °C. The HMF calibration curve was built in the range of 250–25,000 ng/mL at UV detector at 284 nm.

Extract preparation for assays of antioxidant activity

The antioxidant activity of the dark brown sugar was assayed according to the methods of Kim et al. (2015). Dark brown sugar (5 g) was extracted with 45.0 mL of methanol using a reciprocal shaker (MS-NOR30, Major Science, CA, USA) at 100 rpm for 24 h. The extracts were centrifuged (994 g) at 4 °C for 20 min. All extracted solutions were filtered and stored in the dark at − 20 °C. The antiradical ability of the methanol each extract with respect to 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl hydrate (DPPH) was assayed by the method of Shimada et al. (1992). Chelating of ferrous ions was determined by the methods of Shimada et al. (1992). Reducing power was determined spectrophotometrically using the ferricyanide method of Oyaizu (1988).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance using the SPSS statistics program for Windows Version 12 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Duncan’s multiple range test was used to identify the difference between treatments at a 5% significance level (p < 0.05). Principal components analysis (PCA) of physicochemical analysis data for dark brown sugar with different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide was carried out to visualize the similarities among different observations using the XLSTAT-Pro software (Addinsoft, Inc., New York, USA).

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of dark brown sugar

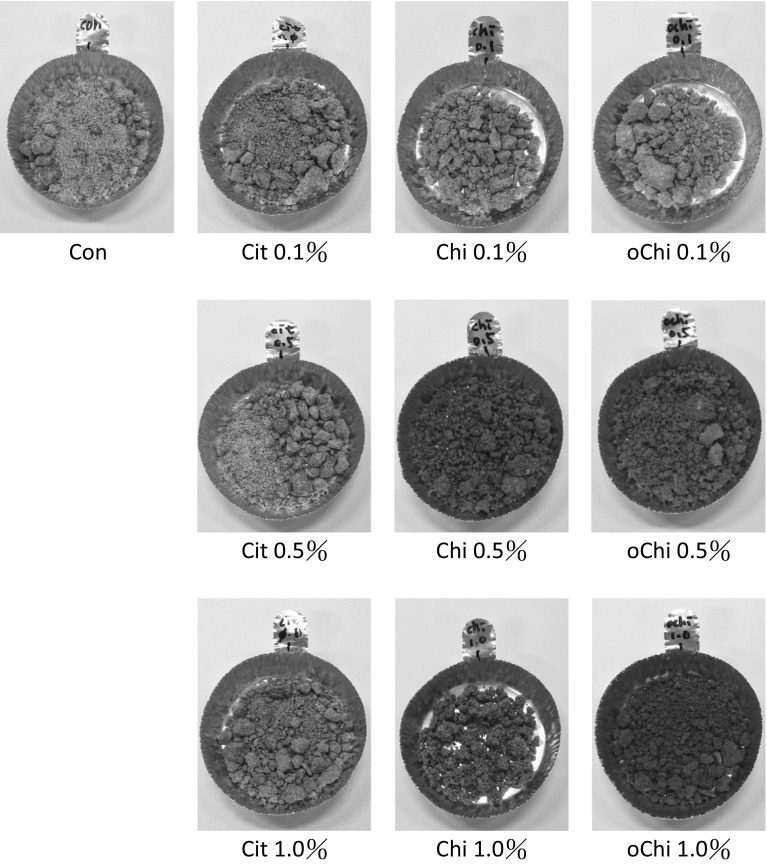

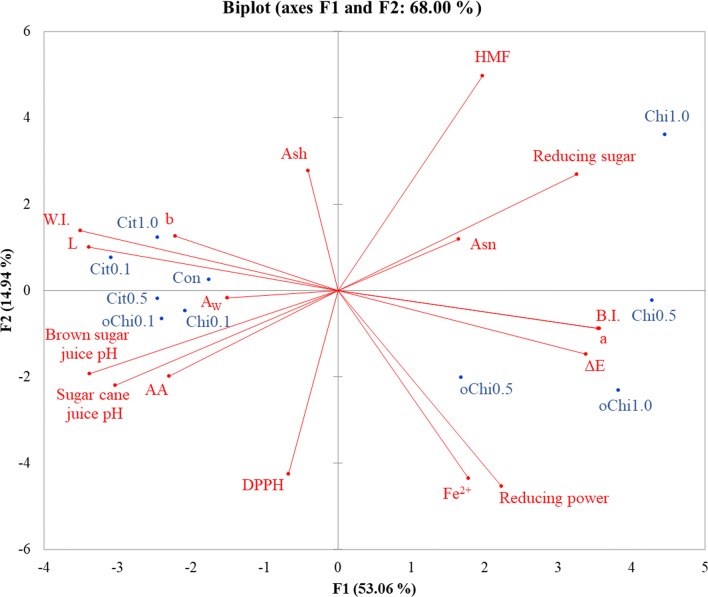

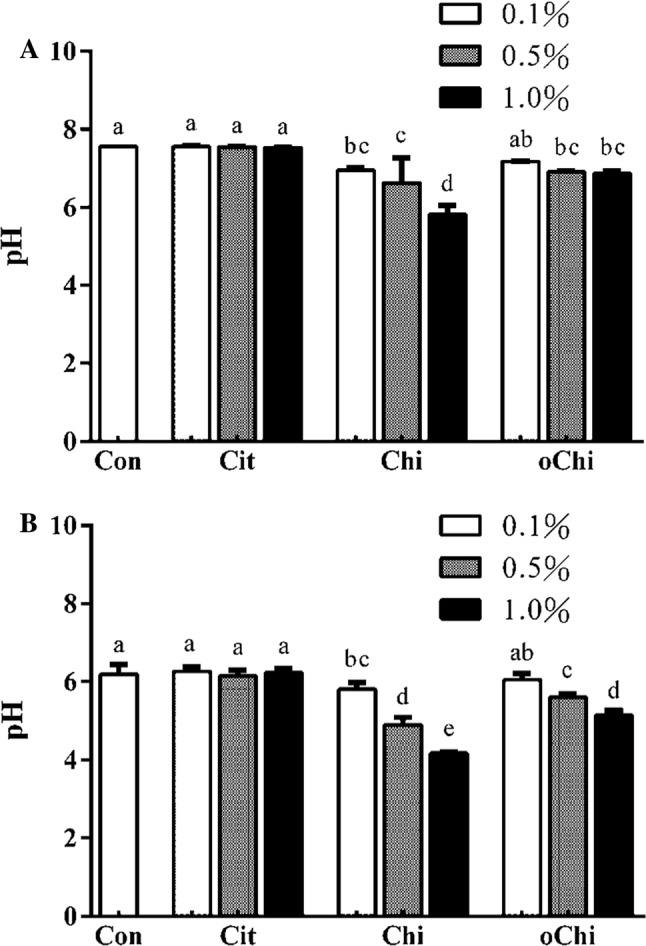

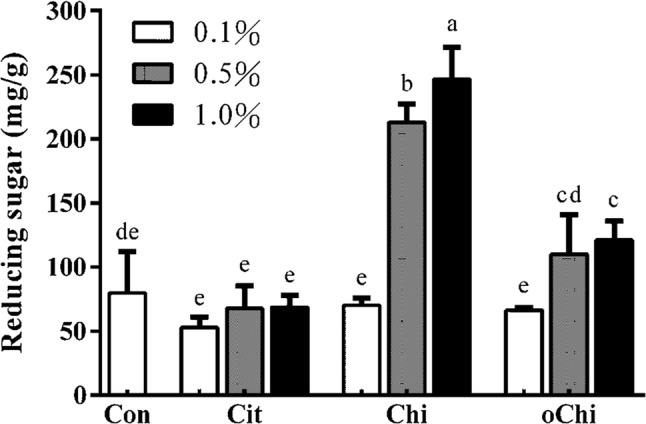

According to Table 1, there were no statistical differences found in L value and WI with the addition of chitosan or chitooligosaccharide at relative low concentration of 0.1%, although the L value and WI showed slight increments. As the addition level elevated to 0.5% and 1%, the L value and WI significantly decreased (p < 0.05), while no differences were found between 0.5% and 1% addition. By contrast, the a value and BI significantly increased with 0.5% and 1% addition of chitosan or chitooligosaccharide (p < 0.05), while the same no differences were found between 0.5% and 1% addition. As a result, the addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide increased the a value and brown index of the dark brown sugar appearance (Fig. 1), perhaps because more reducing sugar and melanoidins were generated which resulted in lightness and white index of dark brown sugar decreased and redness increased. ΔE and brown index of dark brown sugar increased. pH values of dark brown sugar decreased after the making process (Fig. 2). The pH values of sugarcane juice decreased with the addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide (Fig. 2). Addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide at 0.5 and 1.0% levels significantly decreased the pH value of sugarcane juice, the pH values of dark brown sugar decreased significantly (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). The addition of 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan and 1.0% chitooligosaccharide had increased the reducing sugar content of dark brown sugar (Fig. 3), however, they did not significantly dilute the asparagine content of dark brown sugar (Fig. 4). Although more reducing sugar was formed at lower pH during dark brown sugar making process, less acryamide and Maillard reaction would be generated at lower pH condition. The pH of sugar cane juice with chitooligosaccharide did not significantly decrease. We explain these results as follows. The pH decreased as the water present in brown sugar juice was evaporated during heating. Also, amino groups of proteins or chitosans reacted with a carbonyl source in the reducing sugar and initiated the Maillard reaction during heating, resulting in the elimination of water (Ostrowska-Czubenko et al. 2011). Hydrogen ions were released by the Amadori rearrangement, thus decreasing the pH of dark brown sugar (Fig. 2b). And the addition of 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan significantly increased the moisture content of dark brown sugar from 2.1 to 7.8% and 15.4%, respectively. The addition of calcium citrate and chitooligosaccharide did not change the moisture content of dark brown sugar significantly as comparing to the control (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Color of dark brown sugar with different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide

| L | A | B | ΔE1 | W.I.2 | B.I.3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | 72.93 ± 1.00ab | − 3.29 ± 1.44c | 33.48 ± 1.46ab | 0.00 | 56.82 | 55.46 |

| 0.1% Cit | 73.51 ± 4.38ab | − 4.73 ± 1.29c | 31.43 ± 1.98ab | 2.57 | 58.63 | 48.62 |

| 0.5% Cit | 71.80 ± 3.80ab | − 4.67 ± 0.21c | 31.93 ± 2.40ab | 2.37 | 57.15 | 51.37 |

| 1.0% Cit | 67.54 ± 2.56abcd | − 4.76 ± 1.24c | 29.25 ± 0.94b | 7.01 | 56.05 | 48.99 |

| 0.1% Chi | 74.19 ± 2.88ab | − 4.00 ± 1.35c | 32.97 ± 0.89ab | 1.53 | 57.94 | 52.25 |

| 0.5% Chi | 52.86 ± 8.17ef | 6.62 ± 1.68a | 29.45 ± 3.89b | 22.75 | 44.02 | 87.22 |

| 1.0% Chi | 56.78 ± 3.24def | 5.21 ± 1.21ab | 30.55 ± 0.73ab | 18.48 | 46.82 | 80.82 |

| 0.1% oChi | 77.33 ± 6.47a | − 4.17 ± 1.64c | 35.57 ± 2.66a | 4.95 | 57.61 | 54.88 |

| 0.5% oChi | 59.35 ± 11.52cdef | 4.86 ± 3.74ab | 31.24 ± 3.37ab | 15.99 | 48.51 | 77.82 |

| 1.0% oChi | 47.52 ± 11.21f | 5.35 ± 2.92ab | 24.38 ± 4.41c | 28.34 | 41.89 | 77.76 |

Expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Values followed by the different letter within each row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide

1

2

3,

Fig. 1.

Appearance of dark brown sugar with different kinds and amounts of additives. Con, control, Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide

Fig. 2.

The pH value of a sugarcane juices and b dark brown sugar juices with different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide.a–eIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 3.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on reducing sugar content in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a–eIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on asparagine content in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a–eIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Divalent calcium ion has been shown to induce a pH decrease in cookie dough, leading to a reduction in acrylamide formation (Levin and Ryan 2009), possibly due to competitive displacement of protons from sulfur atoms, ionizable oxygen or nitrogen, which share electrons with hydrogen atoms. When the pH is not very high, most protons would be removed prior to the addition of calcium ions; when the pH is high enough, competition would occur between calcium ions and protons (Clydesdale 1988). Despite these expectations, the addition of calcium citrate had no effect on the pH of the dark brown sugars in the present study (Fig. 2).

Reducing sugar in dark brown sugars

No reducing sugars were detected in the sucrose, whereas the experimental lots of dark brown sugar was basically composed of sucrose, glucose and fructose (Dos Santos et al. 2018). Chitosan (0.5% and 1.0%) or chitooligosaccharide (1.0%) addition had significantly increased the amount of reducing sugar in dark brown sugar (Fig. 3). This is because the acidic pH of the chitosan (pH 3.87) and chitooligosaccharide (pH 6.2) will decrease the pH of sugarcane juice, thereby increasing hydrolysis of sucrose to glucose and fructose and generating more reducing sugar after heating process. However, the reducing sugar content of dark brown sugar in the present study was no different between the calcium citrate added groups and control (Fig. 3). Gokmen and Senyuva (2007) reported that when the concentration of calcium cations was increased, the amount of reducing sugar and glucose decreased in a glucose-asparagine model system. No significant decrease in the amount of reducing sugar in dark brown sugar fortified with 0.1–1.0% calcium citrate was observed in this study, indicating this is not always the case in a real sugar system. Calcium influences the rate of decomposition of reaction precursors (Gokmen and Senyuva 2007), and the presence of calcium citrate in the dark brown sugar test did not influence the reaction during heating.

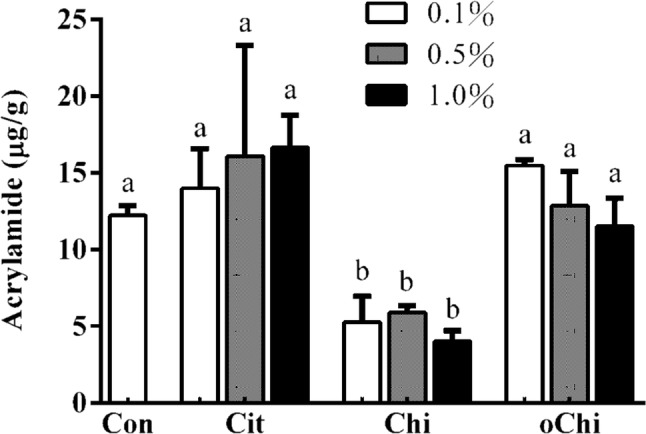

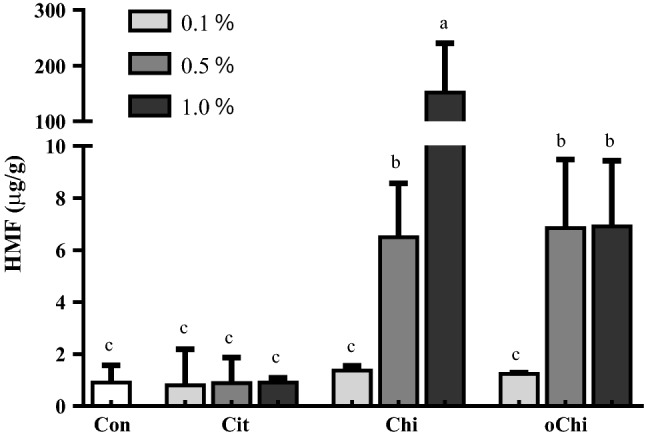

Effects of the addition of calcium citrate, chitosan and chioligosaccharide on the formation of acrylamide and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in dark brown sugars

The presence of calcium cations reduced acrylamide concentrations by increasing hydroxymethylfurfural and furfural concentrations (Gokmen and Senyuva 2007). Gokmen et al. (2007a) postulated that the key intermediate for acrylamide formation, the Schiff base, was inhibited and shifted to another reaction pathway, with the dehydration of glucose leading to hydroxylmethylfurfural and furfural. The reaction proceeded in this way when the concentration of calcium was increased. Nevertheless, the presence of calcium ions was not associated with either a reduction in acrylamide formation or an increase the amount of HMF in the present study (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 5.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on acrylamide formation in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a–bIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 6.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitoligosaccharide on hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) formation in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a, bIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

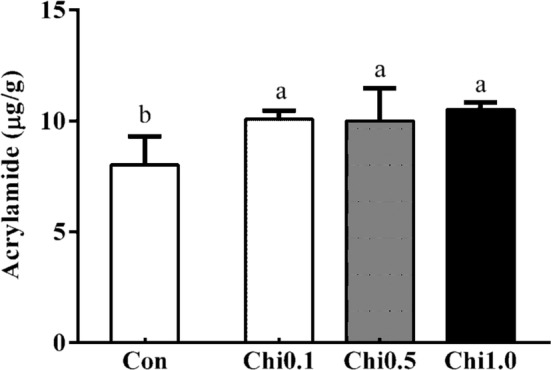

Figure 5 showed that the content of 52–67% acrylamide in the dark brown sugar was mitigated with 0.1–1.0% chitosan addition. The addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide decreased the pH of sugarcane juice (Fig. 2a) and it made the pH of dark brown sugars with chitosan and chitooligosaccharide was lower than that of control (Fig. 2b). The reducing power of dark brown sugar was also increased with 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan addition (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the addition of 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan or chitooligosaccharide increased HMF formation (Fig. 6). Only the pH of dark brown sugar with chitosan and chitooligosaccharide addition was lower than that of other dark brown sugars (Fig. 2). This is due to the low pH condition in dark brown sugar mitigating Maillard reaction and acrylamide formation. When the pH of sugarcane juice adjusted back to pH 7 again, the acrylamide content of dark brown sugars with chitosan addition significant increased (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7). The HMF content (6500–151,643 ppb) of the dark brown sugar with 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan or chitooligosaccharide was significantly higher than that of the control (912 ppb) (Fig. 6). White sugar itself is free of HMF (Polovková and Šimko 2017) because it only contains sucrose. HMF levels in light and dark brown sugar were in the range 11.9–16.4 ppm and 12.3–23.3 ppm, respectively, reported by Risner et al. (2006). The dehydration of reducing sugar via beta-elimination is central in thermally induced sugar degradation under almost anhydrous conditions (Kroh 1994). Therefore, high concentrations of HMF can be measured after thermal and/or acid-catalysed caramelization of d-glucose at 200 °C for 2 h (Kroh 1994). The corresponding reaction of d-fructose leads to significantly increased concentrations of HMF (Telegdy Kovats and Orsi 1973). In a biscuit model (Navarro and Morales 2017), HMF was generated after 1,2-enolization, dehydration and cyclization reactions from Amadori product degradation at an advanced stage of the Maillard reaction and from sugar caramelization. The addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide have induced HMF formation (Fig. 6). This indicates that in the present study, HMF mainly came from chitosan and chitooligosaccharide with much amino groups, which led to more Maillard reaction products during heating (Fig. 6) because asparagines concentration was no different in these groups (Fig. 4). In this scenario, heating of reducing sugars and amino groups would generate significant amounts of HMF and the reducing sugars would react with chitosan and chitooligosaccharide to form more HMF (Fig. 6). The carbonyl group of the reducing sugars fructose or glucose would react with the amino group of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide to form HMF and chitosan-sugar or chitooligosaccharide-sugar conjugates of Maillard reaction products, and the conjugates would also generate HMF during the heating process. In a glucose-asparagine model system (Gokmen and Senyuva 2007), the addition of calcium ion prior to thermal processing increased the formation of HMF and furfural and reduced acryalamide formation. High negative correlation was observed between HMF and acrylamide in the present study (Fig. 8). Labeling studies have shown that sucrose decomposes to release a fructofuranosyl cation and free glucose as a reactive intermediate, which can be dehydrated to release HMF and H+ (Locas and Yaylayan 2008); however, the decomposed sucrose pathway with lower pH was the main reaction generating acryalmide and HMF in our dark brown sugars (Figs. 5, 6).

Fig. 7.

Effect of different amounts of chitosan (pH = 7) on acrylamide formation in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Chi 0.1, 0.1% chitosan; Chi 0.5, 0.5% chitosan; Chi 1.0, 1.0% chitosan. a, bIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 8.

Principal component analysis of physicochemical analysis data for dark brown sugar with different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide; AA, acrylamide; HMF, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural

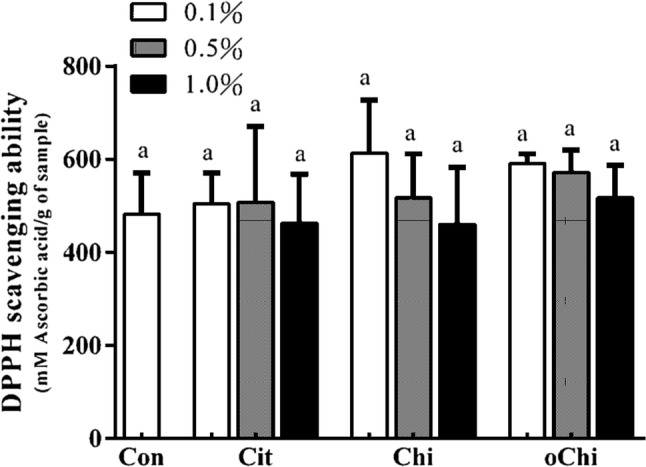

Radical scavenging activity of dark brown sugars

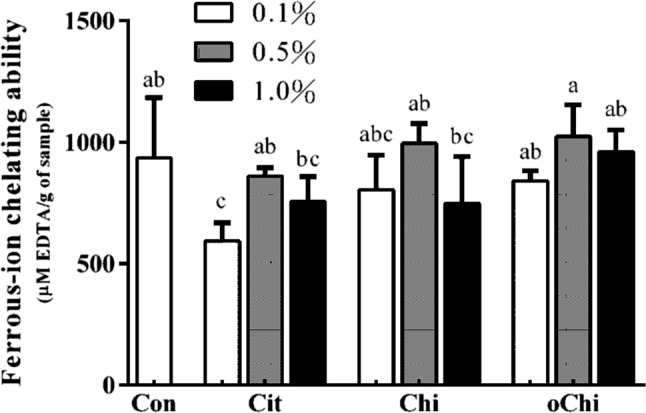

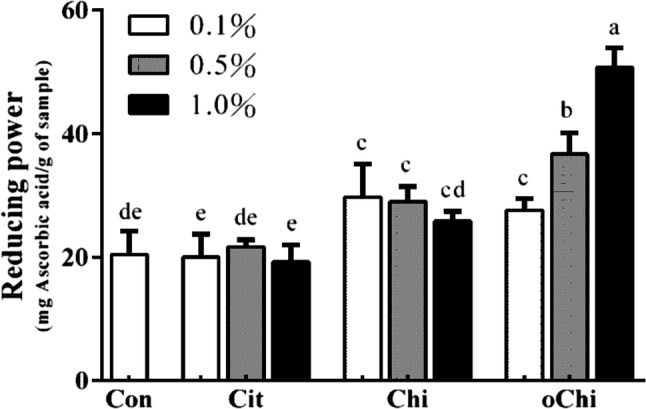

Although chitosan with a high degree of deacetylation showed high radical-scavenging effects (Park et al. 2004) and low molecular weight chitosan also exhibits strong DPPH-scavenging activity (Chien et al. 2007). Dark brown sugar with chitosan, chitooligosaccharide and calcium citrate addition did not change significantly the DPPH scavenging ability and ferrous-ion chelating activity (Figs. 9, 10). This indicates the DPPH scavenging ability and ferrous-ion chelating activity of dark brown sugar might be mainly coming from the phenolic compounds and Maillard reaction products in the dark brown sugar itself. Brown sugar aqueous solutions showed higher antioxidant activity in the ABTS assay at relatively high concentration and weak free radical scavenging activity in the DPPH assay (Payet et al. 2005). Brown sugar may display antioxidant properties arising from polyphenols and Maillard reaction products (Payet et al. 2005). Yen et al. (2008) reported that chitosan from shiitake mushroom stems and crab shells is not an effective scavenger for the DPPH radical. However, the reducing power of dark brown sugars with the presence of 0.1–0.5% chitosan or 0.1–1.0% chitooligosaccharide was higher (p > 0.05) than that of control (Fig. 11). It was reported the reducing power of chitooligosaccharide at the concentration of 2.4 mg/mL was high (0.41–0.46) (Sun et al. 2011). Dark brown sugar with 0.5 and 1.0% chitooligosaccharide displayed higher (p < 0.05) reducing power than control (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on DPPH radical scavenging ability in dark brown sugar. Con: control; Cit: calcium citrate; Chi: chitosan; oChi: chitooligosaccharide. a, bIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 10.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on ferrous-ion chelating ability in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a–c Indicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Fig. 11.

Effect of different amounts of calcium citrate, chitosan, and chitooligosaccharide on reducing power in dark brown sugar. Con, control; Cit, calcium citrate; Chi, chitosan; oChi, chitooligosaccharide. a–eIndicate significant difference between different samples (n = 3; p < 0.05)

Conclusion

Dark brown sugar with chitosan addition generated less acryalmide. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) content in the dark brown sugar with 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan and chitooligosaccharide addition increased significantly. Chitosan addition increased the acrylamide formation when the pH of sugarcane juice was adjusted back to pH 7.0 in dark brown sugar production. Dark brown sugar with 0.5 and 1.0% chitosan and chitooligosaccharide addition appeared more charred. The addition of chitosan and chitooligosaccharide apparently hydrolysis of sucrose in dark brown sugar due to lower pH condition during heating. In order to accommodate consumer groups who like the dark brown sugar flavor, dark brown sugar manufacturers in general should choose sugarcane variety with a lower content of asparagines and reducing sugar as a raw material in order to prevent the final product from containing too much acrylamide. They should generally avoid dark brown sugar containing high levels of acrylamide with 0.5% chitosan addition without pH adjusting.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Taiwan Ocean University and Taipei Medical University through University System of Taipei Joint Research Program (USTP-NTOU-TMU-108-03). The authors thank the edition of this manuscript by Dr. Mark J. Grygier, Center of Excellence for the Oceans at National Taiwan Ocean University.

Complinace with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by all the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acar OC, Pollio M, Di Monaco R, Fogliano V, Gokmen V. Effect of calcium on acrylamide level and sensory properties of cookies. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2012;5:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s11947-009-0317-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amrein TM, Schonbachler B, Escher F, Amado R. Acrylamide in gingerbread: critical factors for formation and possible ways for reduction. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:4282–4288. doi: 10.1021/jf049648b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asikin Y, Kamiya A, Mizu M, Takara K, Tamaki H, Wada K. Changes in the physicochemical characteristics including flavor components and Maillard reaction products of non-centrifugal cane brown sugar during storage. Food Chem. 2014;149:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asikin Y, Hirose N, Tamaki H, Ito S, Oku H. Effects of different drying-solidification processes on physical properties, volatile fraction, and antioxidant activity of non-centrifugal cane brown sugar. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2016;66:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.10.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolomeo MP, Maisano F. Validation of a reversed-phase HPLC method for quantitative amino acid analysis. J Biomol Tech. 2006;17:131–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann M, Grob K. Model studies on acrylamide formation in potato, wheat flour and corn starch; ways to reduce acrylamide contents in bakery ware. Mitt Lebensmittelunters Hyg. 2003;94:406–422. [Google Scholar]

- Brathen E, Kita A, Knutsen SH, Wicklund T. Addition of glycine reduces the content of acrylamide in cereal and potato products. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:3259–3264. doi: 10.1021/jf048082o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Food Safety (2015) Acrylamide in dark brown sugar. Food Safety Focus 2015 Food incident highlight. https://www.cfs.gov.hk/english/multimedia/multimedia_pub/multimedia_pub_fsf_111_03.html. Accessed 23 June 2019

- Chang YW, Sung WC, Chen JY. Effect of different molecular weight chitosans on the mitigation of acrylamide formation and the functional properties of the resultant Maillard reaction products. Food Chem. 2016;199:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TY, Luo HM, Hsu PH, Sung WC. Effects of calcium supplements on the quality and acrylamide content of puffed shrimp chips. J Food Drug Anal. 2016;24:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng WC, Kao YM, Shih DYC, Chou SS, Yeh AI. Validation of an improved LC/MS/MS method for acrylamide analysis in food. J Food Drug Anal. 2009;17:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- Chien PJ, Sheu F, Huang WT, Su MS. Effect of molecular weight of chitosans on their antioxidative activities in apple juice. Food Chem. 2007;102:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesarova Z, Kiss E, Boegl P. Impact of L-asparaginase on acrylamide content in potato products. J Food Nutr Res. 2006;45:141–146. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-802832-2.00021-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clydesdale FM. Minerals: their chemistry and fate in food. In: Smith K, editor. Trace minerals in food. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1988. pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dinç S, Javidipour I, Özbas Ö, Tekin A. Utilization of zero-trans non-interesterified and interesterified shortenings in cookie production. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51:365–370. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0506-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos JM, Quináia SP, Felsner ML. Fast and direct analysis of Cr, Cd and Pb in brown sugar by GF AAS. Food Chem. 2018;260:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokmen V, Senyuva HZ. Acrylamide formation is prevented by diavalent cations during the Maillard reaction. Food Chem. 2007;103:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gokmen V, Acar OC, Koksel H, Acar J. Effects of dough formula and baking conditions on acrylamide and hydroxymethylfurfural formation in cookies. Food Chem. 2007;104:1136–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gokmen V, Akbudak B, Serpen A, Acar J, Turan ZM, Eris A. Effects of controlled atmosphere storage and low-dose irradiation on potato tuber components affecting acrylamide and color formations upon frying. Eur Food Res Technol. 2007;224:681–687. doi: 10.1007/s00217-006-0357-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe WR. Nutritional and functional components of non centrifugal cane sugar: a compilation of the data from the analytical literature. J Food Compos Anal. 2015;43:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James CS. Analytical chemistry of foods. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jung MY, Choi DS, Ju JW. A novel technique for limitation of acrylamide formation in fried and baked corn chips and in French fries. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1287–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2003.tb09641.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Lee JM, Do JS, Bang WS. Antioxidant activities and quality characteristics of omija (Schizandra chinesis Baillon) cookies. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2015;24:931–937. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0120-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroh LW. Caramelisation in food and beverages. Food Chem. 1994;51:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(94)90188-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levin RA, Ryan SM. Determining the effect of calcium cations on acrylamide formation in cooked wheat products using a model system. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:6823–6829. doi: 10.1021/jf901120m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RC, Jang S. Chemical intervention strategies for substantial suppression of acrylamide formation in fried potato products. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;561:393–404. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24980-X_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lineback DR, Coughlin JR, Stadler RH. Acrylamide in foods: a review of the science and future considerations. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2012;3:15–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locas CP, Yaylayan VA. Isotope labelling studies on the formation of 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde (HMF) from sucrose by pyrolysis-GC/MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:6717–6723. doi: 10.1021/jf8010245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M, Morales FJ. Effect of hydroxytyrosol and olive leaf extract on 1, 2-dicarbonyl compounds, hydroxymethylfurfural and advanced glycation endproducts in a biscuit model. Food Chem. 2017;217:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral RA, Mortas M, Dogan M, Sarioglu K, Yazici F. New approaches to determination of HMF. Food Chem. 2014;143:367–370. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.07.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowska-Czubenko J, Pieróg M, Gierszewska-Drużyńska M. State of water in noncrosslinked and crosslinked hydrogel chitosan membranes–DSC studies. Prog Chem Appl Chitin Deriv. 2011;16:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu M. Antioxidative activities of browning products of glucosamine fractionated by organic solvent and thin-layer chromatography. Nippon Shokuhin Kogyo Gakkaishi. 1988;35:771–775. doi: 10.3136/nskkk1962.35.11_771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park PJ, Je JY, Kim SK. Free radical scavenging activities of differently deacetylated chitosans using an ESR spectrometer. Carbohydr Polym. 2004;55:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2003.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payet B, Shum Cheong Sing A, Smadja J. Assessment of antioxidant activity of cane brown sugars by ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays: determination of their polyphenolic and volatile constitutents. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:10074–10079. doi: 10.1021/jf0517703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreschi F, Kaack K, Granby K. The effect of asparaginase on acrylamide formation in French fries. Food Chem. 2008;109:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polovková M, Šimko P. Determination and occurrence of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde in white and brown sugar by high performance liquid chromatography. Food Control. 2017;78:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.02.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta B, Anese M. The effect of salts on acrylamide and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural formation in glucose-asparagine model solutions and biscuits. J Food Nutr Res. 2010;49:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Risner CH, Kiser MJ, Dube MF. An aqueous high-performance liquid chromatographic procedure for the determination of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in honey and other sugar-containing materials. J Food Sci. 2006;71:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.tb15614.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Fujikawa K, Yahara K, Nakamura T. Antioxidative properties of xanthan on the antioxidation of soybean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:945–948. doi: 10.1021/jf00018a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Zhu Y, Xie J, Yin X. Antioxidant activity of N-acyl chitosan oligosaccharide with same substituting degree. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:798–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung WC, Chang YW, Chou YH, Hsiao HI. The functional properties of chitosan-glucose-asparagine Maillard reaction products and mitigation of acrylamide formation by chitosans. Food Chem. 2018;243:141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surh YJ, Tannenbaum SR. Activation of the Maillard reaction product 5-(hydroxmethyl)furfural to strong mutagens via allylic sulfonation and chlorination. Chem Res Toxicol. 1994;7:313–318. doi: 10.1021/tx00039a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Ishmael M, Asikin Y, Hirose N, Mizu M, Shikanai T, Tamaki H, Wada K. Composition, taste, aroma, and antioxidant activity of solidified noncentrifugal brown sugars prepared from whole stalk and separated pith of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) J Food Sci. 2016;81:C2647–C2655. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.13531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tareke E, Rydberg P, Karlsson P, Eriksson S, Tornqvist M. Acrylamide: a cooking carcinogen? Chem Res Toxicol. 2000;13:517–522. doi: 10.1021/tx9901938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telegdy Kovats L, Orsi F. Some observations on caramelisation. Period Polytech. 1973;17:373–385. [Google Scholar]

- Yen MT, Yang JH, Mau JL. Antoxidant properties of chitosan from crab shells. Carbohydr Polym. 2008;74:840–844. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]