Abstract

The aim of the present study was to determine the chemical composition (organic acids—acetic, tartaric, citric; sugars—sucrose, glucose, fructose; total acidity, alcohol content, pH—with FTIR instrument; content of selected mineral compounds—AAS instrument), antioxidant activity, antimicrobial activity and sensory profiles of prepared kombucha tea beverage. Black tea with white sugar as a substrate for kombucha beverage was used as a control sample. The dominant organic acid in kombucha tea beverage was acetic acid (1.55 g/L), followed by tartaric and citric acids. The sucrose (17.81 g/L) was the dominant sugar from detected sugars. Antioxidant activity of beverage tested by reducing power method (1318.56 mg TEAC/L) was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in comparison with black tea (345.59 mg TEAC/L). The same tendency was observed for total polyphenol content which was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in kombucha beverage (412.25 mg GAE/L) than in black tea (180.17 mg GAE/L). Among mineral compounds, the amount of manganese (1.57 mg/L) and zinc (0.53 mg/L) was the highest in kombucha tea beverage. Results of antimicrobial activity of kombucha tea beverage showed strong inhibition of Candida krusei CCM 8271 (15.81 mm), C. glabrata CCM 8270 (16 mm), C. albicans CCM 8186 (12 mm), C. tropicalis CCM 8223 (14 mm), Haemophilus influenzae CCM 4454 (10 mm) and Escherichia coli CCM 3954 (4 mm). Sensory properties of prepared beverage were evaluated overall as good with the best score in a taste (pleasant fruity-sour taste). The consumption of kombucha tea beverage as a part of drinking mode of consumers due to health benefits is recommended.

Keywords: Mineral composition, Black tea, Organic acids, Antioxidant activity, Polyphenols

Introduction

Kombucha tea is a beverage obtained using fermentation of sweet medium, commonly black or green tea, by symbiotic culture of acetic acid bacteria (Gluconobacter, Acetobacter species), lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus, Lactococcus species) and yeasts (Saccharomycodes ludwiga, Zygosaccharomyces bailii etc.) (Villarreal-Soto et al. 2018). This homemade product is usually fermented for 8–10 days with production of acetic acid, small quantities of ethanol and CO2 (Filippis et al. 2018) and slightly acidic, carbonated and sweet taste of product (Vitas et al. 2018).

The products of microbiological activity in kombucha beverage play a vital role in biochemical reactions in the human body. It has been reported that kombucha may prevent chronic diseases and posed antihyperglicemic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic and antihyperlipidemic effects in models (Neffe-Skocińska et al. 2017). Kombucha was proved to exert an antimicrobial activity against pathogens (Reva et al. 2015).

The presence of a variety of chemical compounds in kombucha beverage has been identified, including organic acids (mainly acetic, gluconic, glucuronic acid, citric, L-lactic, malic, tartaric, malonic, oxalic, succinic, pyruvic, and usnic); sugars (sucrose, glucose, and fructose), water-soluble vitamins, amino acids, biogenic amines, purines, pigments, lipids, proteins, hydrolytic enzymes, ethanol, carbon dioxide, polyphenols, minerals (manganese, iron, nickel, copper, zinc, plumb, cobalt, chromium, and cadmium), anions (fluoride, chloride, bromide, iodide, nitrate, phosphate, and sulphate), D-saccharic acid-1,4-lactone, and metabolic products of yeasts and bacteria (Leal et al. 2018). Nowadays, the significance of functional food is growing as people became more concerned about the obesity and prevention of chronic diseases. The probiotics and synbiotics comprise an important sector within the functional food market, however, a majority of probiotic drinks are from dairy and products thereof. The tendency to veganism with consumption of non-dairy nutraceuticals and increased role of lactose intolerance in individuals called for design of new, safe, non-dairy probiotic product, which may become an essential healthy eating food group. Thus, the kombucha and other fermented functional foods like kvass, fermented herb drinks, etc., may substitute functional dairy products for people with lactose intolerance (Prado et al. 2008; Reva et al. 2015).

The main objective of the present study was to investigate chemical composition (organic acids, sugars, antioxidant activity, total polyhenol content, mineral compounds), antimicrobial activity and sensory profiles of kombucha tea beverage prepared in laboratory conditions.

Materials and methods

Preparation of kombucha tea beverage

Kombucha culture was obtained from the local inhabitants of Liešťany village in Slovakia and was maintained in sugared black tea. The tea medium was prepared traditionally by boiling 1 L of distilled water with 30 g of white sugar and 5 g of black tea leaves (Darjeeling, India) for 5 min and allowing to steep for 15 min. The sweetened tea was strained to remove the leaves during transfer to a sterile glass jar (2 L). After cooling to 22 °C, the tea was inoculated with the kombucha culture (pellicle). The jar was covered with a paper towel. Fermentation was conducted at 22 °C for up to 7 days. Black tea whit white sugar was used as a control sample (1 L of distilled water with 30 g of white sugar and 5 g of black tea leaves—Darjeeling, India for 5 min and allowing to steep for 15 min.). All procedures (control sample and kombucha tea beverage) were carried out in triplicate.

Chemicals

All the chemicals used were of analytical grade and were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and CentralChem (Slovakia).

FTIR instrument

The quantification of organic acids (acetic acid, tartaric and citric acid), sugars (sucrose, glucose and fructose), total acidity, alcohol and pH was done with analyzer Alpha P™ (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany). The initial calibration was assembled by the accredited (DAkkS) Institute Heidger (Kesten, Germany). FTIR analysis is based on the use of infra-red light properties (each chemical has its own infra-red signature similar to a fingerprint). Reflected light energy serves to evaluate the results of the analysis using the calibration equations within the equipment’s memory (total acidity—from 0.0 to 13.5 g/L, acetic acid from 0.1 to 1.5 g/L, tartaric acid from 0.0 to 5.4 g/L, citric acid from 0.0 to 6.5 g/L, sucrose from 0.5 to 178.4 g/L, glucose from 0.2 to 125.6 g/L, fructose from 0.1 to 111.5 g/L, alcohol from 0.12 to 20.48%, pH from 2.75 to 4.05). Spectra were recorded in a range from 375 to 4000 cm−1 and the spectral resolution was set to 8 cm−1. Measurements were carried out in single-bounce attenuated total reflectance (SB-ATR) on a diamond ATR-crystal. Spectra were recorded at 40 °C (sample temperature) with background measurements against ultra-pure water. The ATR crystal is covered with a flow-through cell, facilitating sample injection. Injection of 5 ml of sample was performed with a syringe.

Determination of the content of mineral compounds

The analysis of mineral compounds was performed on Varian model AA 240 FS equipped with a D2 lamp background correction system using an air-acetylene flame (air 13.5 L/min, acetylene 2.0 L/min, Varian, Ltd., Mulgrave, Australia). The measured results were compared with multielemental standard for GF AAS (CertiPUR®, Merck, Germany). A 1 g of sample was digested with mixture of HNO3: redistilled water (1:1). Samples were digested in a closed vessel, high-pressure microwave digester (MARS X-press, USA) for 55 min. After cooling to room temperature, the suspension was filtered through Munktell filter paper (grade 390.84 g/m2, Germany) and diluted to 50 ml with distilled water. Thn, the samples extracts were subsequently analyzed for Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn, Co, Cr, Ni, Mn and Fe, using fast sequential atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Varian model AA 240 FS). The wavelengths at which the heavy metals were tested following the calibration process: Cd—228.8 nm, Pb—217.0 nm, Cu—324.8 nm, Zn—213.9 nm, Co—240.7 nm, Cr—357.9 nm, Ni—232.0 nm, Mn—279.5 nm, Fe—241.8 nm.

Antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity was determined by reducing power method according to Oyaizu (1986) with some modification. An amount of 1 mL of sample was mixed with 5 mL of PBS (phosphate buffer, pH 6.6) and 5 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide (w/v) in the test tube. A mixture was stirred thoroughly and heated in water bath at 50 °C for 20 min. After cooling, 5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added. A 5 mL of mixture was pipetted into the test tube and mixed with 5 mL of distilled water and 1 mL of 0.1% (w/v) ferric chloride solution. Absorbance at 700 nm was measured using the spectrophotometer Jenway (6405 UV/Vis, England). Trolox (10–100 mg/L; R2 = 0.99) was used as a standard and the results were expressed in mg/L of Trolox equivalents.

Total polyphenol content

Total polyphenol content was measured in accordance to Singleton and Rossi (1965) using Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. A 0.1 mL of sample was mixed with 0.1 mL of the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 1 mL of 20% (w/v) sodium carbonate and 8.8 mL of distilled water, and left in darkness for 30 min. The absorbance at 700 nm was measured using the spectrophotometer Jenway (6405 UV/Vis, England). Gallic acid (25–300 mg/L; R2 = 0.998) was used as a standard and the results were expressed in mg/L of gallic acid equivalent.

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial activity was tested by the disc diffusion method. Altogether six strains of microorganisms were used in experiment, including four yeasts (Candida krusei CCM 8271, Candida glabrata CCM 8270, Candida albicans CCM 8186, Candida tropicalis CCM 8223) and two Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli CCM 3954, Haemophilus influenzae CCM 4454). All tested strains were from the Czech Collection of Microorganisms. The bacterial and yeast suspensions were cultured in the nutrient broth (Imuna, Slovakia) at 37 °C for 24 h before testing.

A suspension of 0.1 mL of the tested microorganism with density of 105 cfu/mL was spread on the Mueller–Hinton Agar (MHA, Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). Filter paper discs of 6 mm in diameter were impregnated with 15 µL of the tea extract and placed on the inoculated agars. Agars were left at 4 °C for 2 h and then incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. The diameters of the inhibition zones were measured in millimetres after incubation.

Sensory evaluation

The organoleptic properties of kombucha tea beverage were determined by a taste panel consisting of 60 evaluators (from 25 to 65 years of age; 30 women and 30 men). The panelists were asked to evaluate the overall appearance, flavour (overall), flavour (intensity), taste (overall), aftertaste and overall acceptability. All parameters were compared with control sample—sweetened black tea. The ratings were on the 9-point hedonic scale ranging from 9 (like extremely) to 1 (dislike extremely) for each characteristic.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate and the mean of replications with standard deviations were reported. Correlation coefficients were calculated by CORR analysis (P ≤ 0.05). The experimental data were subjected to analysis of variance (Duncan’s test) at the significance level of 0.05 (software SAS 2009.

Results and discussion

Chemical evaluation

The results from quantification (Table 1) of organic acids showed that the dominant was acetic acid (1.55 g/L) followed by tartaric (0.23 g/L) and citric acid (0.05 g/L) in tested kombucha tea beverage. Total acidity of prepared beverage was 2.5 g/L and 3.2 pH. The acetic acid is the chemical compound responsible for acidic smell and taste of kombucha beverages. The acetic acid bacteria produce the acetic acid in kombucha by conversion of sucrose to ethanol and glucose and fructose (Spedding 2015). Amount the acetic acid is strongly influenced by a day of fermentation. In study of Jayabalan et al., (2007), the value of acetic acid in black tea kombucha beverage ranged from 0.22 (3th fermentation day) to 9.51 g/L (15th fermentation day). The content of acetic acid on 6th day of fermentation (1.5 g/L) was comparable with our results after 7th day of fermentation. The determined amount of citric acid (CA) was 0.05 g/L while Jayabalan et al. (2007) detected the citric acid in amount of 0.11 g/L only on third day of fermentation. Citric acid can be synthesized by yeasts and catabolised by cells (Ye et al. 2014). Only 0.04 g/L of citric acid in kombucha beverage prepared with yarrow was found by Vitas et al., (2018). Our results were in agreement with Neffe-Skocińska et al., (2017) who determined the amount of 1.26 g/L (acetic acid) and 0.067 g/L (citric acid) in kombucha beverage fermented 7th day at 25 °C.

Table 1.

Results on quantification of organic acids, sugars, alcohol and pH in prepared kombucha tea

| Parameter | Kombucha tea beverage |

|---|---|

| Total acidity (g/L) | 2.5 ± 0.17 |

| Acetic acid (g/L) | 1.55 ± 0.12 |

| Tartaric acid (g/L) | 0.23 ± 0.05 |

| Citric acid (g/L) | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| Sucrose (g/L) | 17.81 ± 1.22 |

| Glucose (g/L) | 9.35 ± 0.98 |

| Fructose (g/L) | 1.41 ± 0.25 |

| Alcohol (%) | 0.4 ± 0.03 |

| pH | 3.2 ± 0.14 |

Mean ± SD

Oxalic, malic, formic, lactic, tartaric and glucuronic acid could be present in kombucha beverages. Glucuronic acid is considered to be one of the key components found in kombucha tea due to its detoxifying action through conjugation (Jayabalan et al. 2007). Content of alcohol (ethanol) was 0.4% in our beverage that allow to include the kombucha in non-alcoholic drinks group. Content of alcohol is strongly influenced by sugars addition and fermentation time. The concentration of ethanol in kombucha increases with fermentation time until achieves an approximate maximum value of 5.5 g/L on the 20th day of fermentation followed by a slow reduction (Chen and Liu 2000). Another study showed the concentration of ethanol of 0.78% on 7th day with the maximum value of 1.10% on the 10th day of fermentation (Neffe-Skocińska et al. 2017). Higher values of ethanol were achieved due to an addition of sucrose as an initial ingredient. The amount of sucrose of 100 g/L were used for preparing kombucha beverage (Chen and Liu 2000; Neffe-Skocińska et al. 2017) while an amount as low as 30 g/L of sucrose in our study to prepare non-alcoholic beverage. Quantification of sugar content showed that the sucrose (17.81 g/L) was dominant in our kombucha tea beverage, followed by glucose (9.35 g/L) and fructose (1.41 g/L). Sucrose is one of the most commonly applied sugars in kombucha tea production. The content of sucrose is decreasing during the fermentation content as a result of conversion into glucose and fructose by yeast cells. Generally, the content of fructose is lower than glucose during fermentation that suggests that fructose is preferred as the source of carbon by yeast cells (Jayabalan et al. 2014; Neffe-Skocińska et al. 2017).

The analysis of mineral compounds showed (Table 2) that an amount of elements essential for the human body—Fe, Mn, Zn and Ni significantly increased (p < 0.05; r = 0.991) during the fermenting process. Cadmium was not found (decrease from 0.06 mg/L) and the amount of lead (Pb) was less than 0.82 mg/L in kombucha tea beverage in comparison with sweet black tea. Decreased Ca and Pb concentration in the drink indicates that the kombucha culture can detoxify beverage that was an interesting finding. This is due to the fact that kombucha culture is biosorbent. This means that it has certain metal-sequestering properties that allow it to accumulate and bind heavy metal contaminants onto its cellular structure. Results from Mamisahebei et al., (2007) have shown that kombucha culture used in the brewing is very effective in cleaning up heavy metals such as arsenic, chromium, and copper from beverages as well as wastewater. It is worth noting that, according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR 2007), the toxic blood Pb level is 0.2 mg/L for an adult that is higher than the concentration of Pb in kombucha tea in the present study. Thus, our results reveal that the kombucha beverage does not represent a potential health risk regarding the content of toxic elements. Cr was not found in the investigated samples. The Co content did not increase in kombucha tea beverage probably of its incorporation in vitamin B12 because the B-group vitamins (mainly B1, B6 and B12) are mainly produced during fermentation process (Leal et al. 2018). Our results are comparable with Bauer-Petrovska and Petrushevska-Tori (2000), who described the similar trend of the content of Fe, Mn, Ni and Cu increasing due to metabolic activity of kombucha.

Table 2.

Results on quantification of mineral compounds in black tea and kombucha tea beverage

| Mineral compounds (mg/L) | Sweet black tea | Kombucha tea beverage |

|---|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) | 0.25 ± 0.02b | 0.31 ± 0.02a |

| Manganese (Mn) | 1.22 ± 0.11b | 1.57 ± 0.13a |

| Zinc (Zn) | 0.31 ± 0.07b | 0.53 ± 0.06a |

| Copper (Cu) | 0.03 ± 0.01b | 0.14 ± 0.02a |

| Cobalt (Co) | 0.24 ± 0.11b | 0.23 ± 0.02a |

| Nickel (Ni) | 0.36 ± 0.08b | 0.42 ± 0.05a |

| Chrome (Cr) | n.d. | n.d. |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 0.06 ± 0a | n.d. |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.82 ± 0.11a | 0.12 ± 0.03b |

Mean ± SD

n.d. not detected; different letters in row denote mean values that statistically (p < 0.05) differ one from another

Antioxidant activity and total polyphenol content evaluation

Antioxidant activity of kombucha tea beverage tested by reducing power was compared with the activity of sweet black tea. Results showed that the activity of fermented kombucha tea was several times higher (Table 3). Fu et al. (2017) found the highest antioxidant activity of kombucha tea in low-cost green tea in comparison with black low-cost tea tested by DPPH and reducing power method. In study of Amarasinghe et al., (2018) the increase of activity of fermented black tea in comparison with non-fermented determined by ORAC and DPPH methods was not identified. Also Pure and Pure, (2016) confirmed that the fermented black tea shared higher antioxidant activity (15.65%) by DPPH method than non-fermented black tea (26.16%). According to Essawet et al., (2015), the main antioxidants in fermented kombucha tea beverages were polyphones and tea fungus metabolites such as vitamins and organic acids. For this reason, the fermented kombucha tea usually expresses the higher antioxidant potential in comparison with non-fermented tea.

Table 3.

Antioxidant activity and total polyphenol content in sweet black tea and kombucha

| Parameter | Sweet black tea | Kombucha tea beverage |

|---|---|---|

| Reducing power (mg TAEC/L) | 345.59 ± 3.58b | 1318.56 ± 5.02a |

| Total polyphenols (mg GAE/L) | 180.17 ± 2.41b | 412.25 ± 3.86a |

Mean ± SD

TEAC trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity, GAE gallic acid equivalent; different letters in row denote mean values that statistically (p < 0.05) differ one from another

Total polyphenol content of 412 mg GAE/L in kombucha tea was higher than 180.17 mg GAE/L in sweet black tea (Table 3). In Aidoo (2015) study the kombucha tea shared 2.4-fold and 7.3-fold higher phenolic content at concentrations of 2.5 and 5.0 mg/mL, that was significantly higher (p < 0.05, r = 0.898) than in non-fermented tea. Significant regression coefficient (p < 0.05, r = 0.999) was observed in our study between the amount of total polyphenols and antioxidant activity (reducing power).

Antimicrobial activity evaluation

Kombucha tea beverage showed antimicrobial activity against four tested Candida and two gram-negative bacteria species (Table 4). The best antimicrobial activity was determined against Candida glabrata CCM 8270 of 16.02 mm, followed by Candida krusei CCM 8271 of 15.81 mm. Kombucha tea beverage is known to show a remarkable antimicrobial activity against a broad range of microorganisms responsible for infectious diseases. The antimicrobial activity is attributed to the low pH value, especially in the presence of acetic acid. Acetic acid in concentration of 1 g/L can inhibit pathogenic and spore-forming bacteria (Tu and Xia 2018). Acetic and other organic acids can influence the antimicrobial activity by cytoplasmic acidification and accumulation of dissociated acid anion to toxic levels (Veličanski et al. 2014).

Table 4.

Results of antimicrobial activity (mm)

| Sample | Candida krusei CCM 8271 | Candida glabrata CCM 8270 | Candida albicans CCM 8186 | Candida tropicalis CCM 8223 | Escherichia coli CCM 3954 | Haemophilus influenzae CCM 4454 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet black tea | 6 ± 0.21b | 6.5 ± 0.35b | 6 ± 0.17b | 5.2 ± 0.58b | 3.5 ± 1.1b | 1.1 ± 0.05b |

| Kombucha tea beverage | 15.81 ± 1.1a | 16 ± 1.25a | 12 ± 1.47a | 14 ± 0.98a | 10 ± 0.46a | 4 ± 0.11a |

Mean ± SD; different letters in row denote mean values that statistically (p < 0.05) differ one from another

Kombucha may contain the antibiotic substances with antimicrobial activity (Watawana et al. 2015). Our results on inhibition of Candida albicans CCM 8186 growth (12 mm) are comparable with Yuniarto et al., (2016), who identified the strong activity (after 6 days of kombucha fermentation) against Candida albicans (15.36 mm). Kombucha tea beverage showed the antimicrobial activity against Haemophilus influenzae CCM 4454 of 10 mm and Escherichia coli CCM 3954 of 4 mm. In study of Battikh et al., (2013), the antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 was detected but the inhibition zone was larger (10.5 mm) than in our study. Veličanski et al., (2014) determined the antimicrobial activity of lemon balm kombucha beverage for Escherichia coli of 11.3 mm. In our mind, the kombucha tea beverage showed good antimicrobial activity in the present study and this product has a potential to be used as an antimicrobial agent.

Evaluation of sensory properties

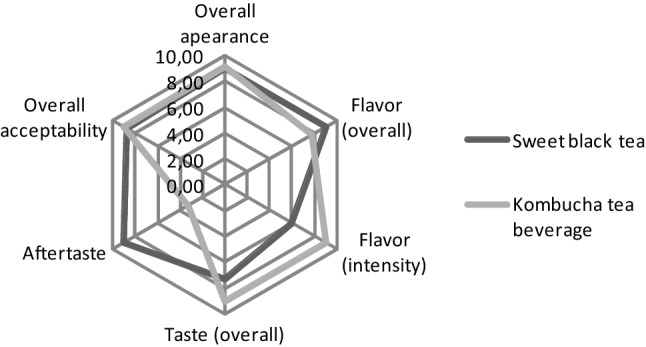

The results of overall appearance and overall acceptability of sweet black tea and kombucha beverage were not differ significantly (Fig. 1). The flavor (overall), flavor (intensity) and taste of kombucha tea received better evaluation. The prepared kombucha tea attracted evaluators with pleasant fresh sour-fruity taste. Some evaluators felt the „vinegar taste“, while other—pleasant fruity and sour aftertaste. Generally, the kombucha tea beverage was evaluated as harmonic and pleasant. In study of Vitas et al., (2018), the prepared yarrow kombucha beverages had acidic and pleasant taste and odour characteristic for the used extracts. Our results are comparable also with high sensory evaluation of kombucha beverages in study of Neffe-Skocińska et al. (2017). In their study the general quality was average, examinators detected mainly tea, lemon and sour smell, while the acetic, yeast and other smells were barely detectible. In terms of sensory discriminants that describe the taste profile of the beverages, the lemon, tea and sour tastes were barely noticeable with the highest intensity. High clarity and similar colour tone were typical for analyzed beverages.

Fig. 1.

Results of sensory evaluation (sum of all evaluators)

Conclusion

Sweetened black tea is a good medium for kombucha fermentation. In our study, the kombucha tea beverage showed a higher amount of mineral compounds like iron, zinc, manganese, antioxidant activity as well as total amount of polyphenols in comparison with non-fermented black tea. Results of chemical evaluation showed the acetic acid was dominant, which is responsible for sour taste of beverage and maintain the low pH of product. The antimicrobial activity was the highest for Candida species (average ~ 14.45 mm). Strong antimicrobial activity was determined for Haemophilus influenzae species (10 mm). The antimicrobial activity could be attributable to low pH and the content of acetic acid in the product. From the sensory evaluation point of view, the prepared beverage was pleasant with positive fresh sour-fruity taste. The results of our study reveal that the kombucha beverage can be a source of good alternative medicine showing the health benefits to the human body.

Acknowledgements

This work was co-funded by the European Community project no 26220220180: Building the Research Centre “AgroBioTech” (50%) and VEGA 1/0411/17 (50%).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2007) Public health statement lead. U.S. Departament of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Retrieved June 11, 2017, from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp13-c1-b.pdf

- Aidoo E (2015) Studies on the cytotoxicity and antioxidant activity of tea kombucha. Dissertation work, University of Ghana. 2015. 65 pp

- Amarasinghe H, Weerakkody NS, Waisundaza VY. Evaluation of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of kombucha “tea fungus”. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6:659–665. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battikh H, Chaieb K, Bakhrouf A, Ammar E. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of black and green kombucha teas. J Food Biochem. 2013;37:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2011.00629.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer-Petrovska B, Petrushevska-Tori L. Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2000;36:201–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00342.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Liu BY. Changes in major components of tea fungus metabolites during prolonged fermentation. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;89:834–839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essawet NA, Cvetkovic D, Velicanski A, Čanadanovič-Brunet J, Vulic J, Maksimovic V, Markov S. Polyphenols and antioxidant activities of kombucha beverage enriched with coffeeberry extract. Chem Ind Chem Eng Q. 2015;21:399–409. doi: 10.2298/CICEQ140528042E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filippis F, Troise AD, Vitaglione P, Ercolini D. Different temperatures select distinctive acetic acid bacteria species and promotes organic acids production during kombucha tea fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2018;73:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu C, Yan F, Cao Z, Xie F, Lin J. Antioxidant activities of kombucha prepared from three different substrates and changes in content of prebiotics during storage. Food Sci Technol. 2017;34:123–126. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612014005000012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan R, Marimuthu S, Swaminathan K. Changes in content of organics acids and tea polyphenols during Kombucha tea fermentation. Food Chem. 2007;102:392–398. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayabalan R, Malbaša RV, Lončar ES, Vitas J, Sathishkumar M. A review on Kombucha tea—microbiology, composition, fermentation, beneficial effects, toxicity, and tea fungus. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2014;13:538–550. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal JM, Suaréz LV, Jayabalan R, Oros JH, Escalante-Aburto A. A review on health benefits of kombucha nutritional compounds and metabolites. CYTA: J Food. 2018;16:390–399. [Google Scholar]

- Mamisahebei S, Khaniki GRJ, Torabian A, Nasseri S, Naddafi K. Removal of arsenic from an aqueous solution by pretreated waste tea fungal biomass. Iran J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2007;4:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Neffe-Skocińska K, Sionek B, Šcibiszi I, Kolozyn-Krajewska D. Acid contents and the effect of fermentation condition of kombucha tea beverage on physicochemical, microbiological and sensory properties. CYTA: J Food. 2017;15:601–607. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2017.1321588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browning reaction-antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr. 1986;44:307–314. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prado FC, Parada J, Pandey A, Soccol CR. Trends in non-dairy probiotic beverages. Food Res Int. 2008;4:111–112. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pure AE, Pure ME. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of kombucha beverages prepared using banana peel, common nettles and black tea infusions. Appl Food Biotechnol. 2016;3:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Reva ON, Zaets IE, Ovcharenko LP, Kukharenko OE, Shpylova SP, Podolich OV, Vera JP, Kozyrousa NO. Metabarcoding of the kombucha microbial community grown in different microenvironments. AMB Express. 2015;5:2–8. doi: 10.1186/s13568-015-0124-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS . Users guide version 9.2 SAS/STAT (r) Cary: SAS Institute Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic. 1965;6:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Spedding G (2015) So what is kombucha? An alcoholic or a non-alcoholic beverage? A brief selected literature review and personal reflection. BDAS, LLC http://alcbevtesting.com/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/WhatIsKombucha_BDASLLC_WPSPNo2_Oct-4-2015.pdf

- Tu YY, Xia HL. Antimicrobial activity of fermented green tea liquid. Int J Tea Sci. 2018;6:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Veličanski A, Cvetkovič D, Markov SL, Šaponjac VTT, Vulič JJ. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of the beverage obtained by fermentation of sweetened lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) tea with symbiotic consortium of bacteria and yeast. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2014;52:420–429. doi: 10.17113/ftb.52.04.14.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal-Soto SA, Beaufort S, Bouajila J, Souchard JP, Taillandier P. Understanding kombucha tea fermentation. A review. J Food Sci. 2018;83:580–588. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitas JS, Cvetanovic AD, Maškovič PZ, Švarc-Gajič JV, Malbaša RV. Chemical composition and biological activity of novel types kombucha beverages with yarrow. J Funct Foods. 2018;44:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watawana MI, Jayawardena N, Gunawardhana CB, Waisundara VY (2015) Health, wellness, and safety aspects of the consumption of kombucha. J Chem, 1–11

- Ye M, Yue T, Yuan Y. Evaluation of polyphenols and organic acids during the fermentation of apple cider. J Food Agric. 2014;94:2954–2957. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuniarto A, Anggadiredja K, Aqidah RAN. Antifungal activity of kombucha tea against human pathogenic fungi. J Pharm Clin Res. 2016;9:253–255. [Google Scholar]