Abstract

Yam soluble protein (YSP) has been reported to have many physiological activities, such as scavenging free radicals, immune activation, and anti-hypertensive activities. Protein solubility and emulsifying activity are important protein-associated functional properties for the application of proteins in food systems. During this study, the factors of protein concentration, pH, temperature and salt concentration that influenced the solubility of YSP were investigated. As a result, the solubility was minimal near its isoelectric point (pH 3.5) and was highest at 45 °C in a temperature range of 40–60 °C. With an increase of protein concentration, the solubility decreased. According to the results of response surface methodology analysis, the interaction between pH and temperature on the solubility of YSP was significant, and the maximum solubility (87.5%) was obtained when the temperature was close to 40 °C, the pH was approximately 7 and the NaCl concentration approached 0.5 mol/L. As the protein concentration increased, the average particle size of the YSP emulsion decreased, and the particle size distribution gradually became balanced. Additionally, the microphotograph of the YSP emulsion reflected its distribution. The results of this study will provide data and a theoretical basis for the understanding of YSP’s physicochemical properties and its application in the food industry.

Keywords: Yam, Protein, Solubility, RSM, Emulsifying properties

Introduction

Yams belong to the genus Dioscorea (family Dioscoreaceae), and they are planted in parts of Asia, Africa, South America, and the Caribbean and South Pacific islands (Asiedu and Sartie 2010). Since ancient days, yam has been used for its various therapeutic effects (Wang et al. 2006). Additionally, the whole yam has been demonstrated to be effective in the prevention and treatment of diabetes and digestive diseases, and it has been used for promoting immune function, nourishing the liver and kidneys, invigorating the lung and tonifying the spleen (Zhang et al. 2011). It has been reported that the general yam components (dry-weight basis) are 75–84% starch, 6–8% crude protein and 1.2–1.8% crude fiber (Liu and Lin 2010).

With the increase in market demand for protein ingredients, proteins have been isolated from various sources (Henchion et al. 2017). Plant proteins, among a variety of non-animal protein sources, have been widely used as food ingredients due to their prominent and various functional properties and abundant supply (Amarowicz 2015; Glusac et al. 2017). Many studies have shown that tuber storage proteins have many physiological activities: patatin (from potato) has lipid acyl hydrolase and acyl transferase activities (Andrews et al. 1988); sporamin (from sweet potato) has trypsin inhibitor, dehydroascorbate reductase and monodehydroascorbate reductase activities (Hou et al. 1999); and tarin (from taro) has lectin activity (Bezerra et al. 1995). Regarding yam, some studies have shown that the yam storage protein (YSP) dioscorin has many physiological activities, such as carbonic anhydrase (CA), dehydroascorbate (DHA) reductase, respiratory epithelial cell protection, immune activation and anti-hypertension activities (Xue et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2015; Xue et al. 2015).

Protein solubility and emulsifying activity are important protein-associated functional properties (Hu et al. 2018). Many studies have shown that the functionalities, such as emulsifying, foaming, viscosity and sensory properties, are closely linked to the solubility of proteins (Wang et al. 2013), and with the increase of protein solubility, these properties have been correspondingly improved (Wang et al. 2008; Tsumura et al. 2005). Therefore, it is of great significance to study the solubility of proteins. Emulsification refers to the properties of water and oil mixed together to form an emulsion, which can change the original taste of foods and cover the undesired flavors. Many traditional foods along with many new processed foods are emulsions or multiphase systems with emulsion (Håkansson 2016). Thus, the emulsifying properties of proteins are of great significance in food processing.

The protein content of yams (6–8% dry-weight basis) is low, but yams are a notably rich resource in Asia. In a previous study, we have carried out preliminary experiments on the solubility, emulsification, foaming and gelation properties of YSP (Hu et al. 2018). In this study, the solubility and emulsifying activity of YSP were investigated by different experimental systems.

Materials and methods

Materials

The rhizoma of yams (Dioscorea opposita Thumb.) used in this study were purchased from a local market (Shenyang, China). Upon arrival to the laboratory, the yams were stored under room temperature until use. All of the reagents used in this study were of reagent grade unless otherwise stated.

Preparation of YSP

Yams were washed, cut into small pieces, added to a 0.1% (w/v) sodium bisulfite solution (1 L/kg of yam) to reduce oxidative browning, ground and centrifuged at 5000g for 20 min. The supernatant was then filtered through a double-layer cheese-cloth, and the pH of the filtrate was adjusted to near 3.5, using 1 mol/L HCl. The slurry was then magnetically stirred for 1 h and centrifuged for 20 min. The precipitate was resolubilized in distilled water and was then adjusted to pH 7 using 1.0 mol/L NaOH; then, it was magnetically stirred for another hour, ultrafiltered and lyophilized. Then, the protein powder was stored in a desiccator until use (Hu et al. 2018).

Protein solubility

Protein solubility of YSP was measured according to the method described by Casella and Whitaker (1990). The YSP was solubilized in distilled water, 1.0 mol/L NaCl or 1.0 mol/L CaCl2 solutions (1% YSP, w/v) by vortexing. After the pH of the solutions was adjusted from 1 to 10 using 0.5 mol/L HCl or 0.5 mol/L NaCl, the YSP solutions were magnetically stirred for 1 h and centrifuged at 5000 g for 20 min. The protein concentrations of the supernatants were measured according to Feist and Hummon (2015) using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The formula, (protein content in the supernatant)/(protein content in the YSP solution) × 100%, was used to calculate the protein solubility (Hu et al. 2018).

To better clarify the effect of the interactions of temperature, pH and NaCl concentrations on protein solubility, the response surface methodology (RSM) was used in this study. YSP solutions (1%, w/v) were prepared by dissolving YSP powder (from the same batch) in distilled water or NaCl solutions with different concentrations (0.00, 0.05, 0.10, 0.25 and 0.50 mol/L), that were adjusted to pH of 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8 and were then heated in a water bath at 40, 45, 50, 55 or 60 °C for 15 min. After the solutions were centrifuged, the absorbance of the supernatant was evaluated at 595 nm using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (722, Shanghai Precision Instrument Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). Using the Design-Expert 8.0.6 software, the protein solubility was designed as a response to optimize the three factors—temperature, pH and NaCl concentration—by central composite, then the optimal condition of these three factors were selected, and the correlation of these three factors to protein solubility was simulated.

Emulsifying activity index

The emulsifying activity index (EAI) of each YSP emulsion was determined according to the method of Liu et al. (2012) with some modifications. YSP solutions of different concentrations (0.1, 0.3 and 0.5%, w/v) were prepared by dissolving YSP powder in distilled water and stirring with a magnetic stirrer for 1 h at room temperature. All of these solutions were adjusted to pH 7.0 using 1.0 mol/L HCl or 1.0 mol/L NaOH. The YSP emulsions (12 mL) were prepared by adding 3 mL peanut oil to 9 mL YSP solutions, and then the mixtures were homogenized using an XHF-DF high-speed homogenizer (TG16G, Changsha, China) for 1 min at 10,000 rpm. An aliquot of emulsion (20 µL) was taken from the bottom of the homogenized emulsion immediately after homogenization, and it was diluted in 3 mL of a 0.1% SDS solution. After mixing the diluted emulsion with a vortex, the absorbance of dilute emulsions was evaluated at 500 nm using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (722, Shanghai Precision Instrument Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). The following equation was used to calculate the EAI:

where D is the dilution factor, A is the absorbance of the diluted emulsions, C is the initial protein concentration of the YSP solution (g/mL), φ is the optical path (0.01 m), and θ is the oil volume fraction used to form the emulsion.

Emulsion particle size distribution

YSP was dissolved in distilled water, and the pH of the solution was adjusted. The solution was then centrifuged at 5000 g for 20 min. After centrifugation, 12 mL of supernatant of the protein solution mixed with 4 mL of peanut oil was homogenized by a high-speed disperser (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) for 1 min at a rotation rate of 10,000g. Immediately after the homogenization, the emulsion (0.1 mL) was added to 4 mL of a 0.1% SDS solution (w/v). The particle size distribution of the YSP emulsion was measured with a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Nano ZS90 nanoparticle size and zeta potential meter, Malvern Corporation, UK). The particle size distribution of YSP emulsions at seven different protein concentrations (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0% and 3.0% w/v, at pH 7), three different pH values (3, 7 and 10) and four different NaCl concentrations (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5% and 1.0% w/v, at pH 7) were determined.

Optical microscopy

YSP solutions of different concentrations (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0% and 3.0%, w/v) were prepared by dissolving YSP powder in distilled water. All of these solutions were adjusted the pH to 7.0 with 1.0 mol/L HCl or 1.0 mol/L NaOH. After that step, 12 mL supernatant of protein solution mixed with 4 mL of peanut oil was homogenized by a high-speed disperser at a rotation rate of 10000 g for 2 min. A drop of emulsion was placed between a microscope slide and a cover slip. Then, the microscopic image of YSP was observed by using an optical microscope (UB202i, Chongqing Aopu Guangdian Technology Co. Ltd, Chongqing, China). The images of the emulsions were captured using a camera connected to digital image processing software (S-Viewer) installed on a computer. The images of the fresh emulsion and the emulsion after standing for 1 h were recorded, since the emulsion droplets were still unstable after half an hour.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The collected data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). The Duncan’s multiple range test was used to analyze differences between treatments (P < 0.05).

Results and discussion

Solubility of YSP

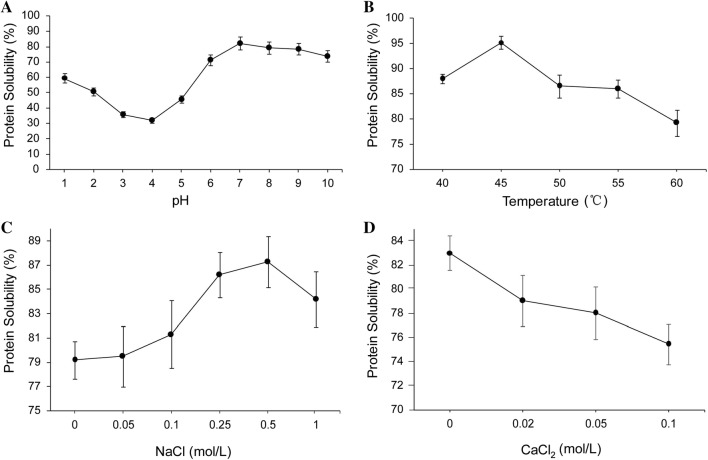

In our previous study, alkali-extraction and acid-precipitation method was optimized using response surface methodology and the experimental yield of YSP reached 57.7% with a 65.3% protein concentration (Zhao et al. 2015; Hu et al. 2018). Solubility is very critical among the functional properties of proteins because their ability to hydrate and dissolve in water determines many functional performances of proteins (Yuliana et al. 2014). The solubility curves of YSP plotted as a function of pH, temperature and NaCl concentrations, respectively, are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Effect of pH (a), temperature (b), NaCl (c) and CaCl2 (d) concentrations on the solubility of YSP

Effects of pH on the solubility of YSP

The solubility behavior of YSP as a function of pH can be deduced from Fig. 1a. A minimum solubility was detected at about pH 3.5, which corresponded to its protein isoelectric point (Zhao et al. 2015). The electrostatic repulsion was reduced due to the balance of positive and negative charges, which limited the solubility of YSP at pH 3.5. The maximum solubility was observed at pH 7. At lower or higher pH than the isoelectric point, a protein has either net positive or net negative charges, which causes the protein molecule to be separated by an electrostatic repulsive force, and the native structure of the protein is disrupted, shifting the equilibrium towards an unfolded form and subsequently exposing the buried functional groups in protein molecule, thereby leading to an increase in protein solubility (Yuliana et al. 2014). The assumption was further verified by the maximum fluorescence intensity (Fmax) of YSP at different pH, illustrating more internal hydrophobic groups were exposed within an alkaline pH range (Hu et al. 2018).

Effects of temperature on the solubility of YSP

The influence of temperature on the solubility of YSP is presented between 40 and 60 °C in Fig. 1b. Between the temperatures of 40 and 45 °C, the solubility increased with the temperature, which indicated that there was no protein aggregation or coagulation in this temperature range. With temperature increased up to 45 °C, the increased kinetic energy of the solution caused a slight increase in protein solubility. At the higher temperatures (45–60 °C), excessive protein denaturation with some coagulation may have occurred, which reduced the solubility of the protein.

Effects of NaCl and CaCl2 on the solubility of YSP

The conformational stability and solubility of proteins are sensitive functions of solvent composition. The effect of salts on the solubility of proteins in aqueous solution is a strong function of the ionic species presented (Ettoumi et al. 2015). It has been reported for a series of Na+ salts that the observed preferential hydration is mainly due to the perturbation of surface free energy change at the protein-solvent interface caused by the addition of salts (Biedermann and Schneider 2016).

As shown in Fig. 1c, the solubility of YSP increased with the NaCl concentration up to 0.5 mol/L but decreased when the NaCl concentration was more than 0.5 mol/L. Salts can stabilize proteins at low concentrations, depending on the ionic strength of the medium. The addition of a small amount of neutral salt ions increased the surface charge of the protein molecules and enhanced the role of the protein molecules and water molecules such that the solubility of the protein in aqueous solution increased (the NaCl concentration increased from 0 to 0.5 mol/L, while the solubility increased from 79.2 to 87.3%). At high concentrations, however, salts can exert specific effects on proteins, resulting in the denaturation or salting out of proteins (either precipitation or crystallization). Thus, a further increase in NaCl concentration resulted in decreased solubility.

In contrast, from previous studies, such salts as CaCl2, BaCl2, and MgCl2 were known as protein destabilizers and salting-in salts (Zhao 2016), which showed little preferential hydration. As shown in Fig. 1d, the protein solubility decreased as the CaCl2 concentration increased because CaCl2 could induce protein unfolding, promote hydrophobic interactions among protein molecules, reduce the ability of combining protein and water (Ma et al. 2012), and ultimately reduce the solubility of YSP.

Effects of pairwise interactions of temperature, pH and NaCl concentrations on the solubility of YSP

The study of the effects of pairwise interactions of temperature, pH and NaCl concentrations on the solubility of YSP was based on RSM. The center composite design is shown in Table 1. According to Fig. 2 and Table 2, the response surface model was very significant (P < 0.0001). The effects of pH and temperature on the solubility of YSP were significant, whereas the interaction between pH and NaCl concentration, as well as the interaction between temperature and NaCl concentration, were not. The descending order in which the three factors affect solubility is temperature, pH and NaCl concentration. According to RSM, the maximum solubility (87.5%) was obtained when the temperature was close to 40 °C, the pH was approximately 7 and the NaCl concentration approached 0.5 mol/L, which was largely consistent with the actual test results.

Table 1.

Design approach and experimental results of response surface methodology

| Run | Factor 1 A:pH |

Factor 2 B:Temperature (°C) |

Factor 3 C:NaCl (mol/L) |

Response 1 Solubility (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 86.1 |

| 2 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.00 | 72.5 |

| 3 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 78.8 |

| 4 | 5.00 | 55.00 | 0.10 | 52.6 |

| 5 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 77.6 |

| 6 | 5.00 | 55.00 | 0.50 | 56.3 |

| 7 | 6.00 | 60.00 | 0.25 | 47.8 |

| 8 | 7.00 | 40.00 | 0.50 | 87.5 |

| 9 | 4.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 49.8 |

| 10 | 7.00 | 45.00 | 0.10 | 73.1 |

| 11 | 5.00 | 45.00 | 0.50 | 80.1 |

| 12 | 7.00 | 55.00 | 0.10 | 66.2 |

| 13 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 1.00 | 69.5 |

| 14 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 79.7 |

| 15 | 5.00 | 45.00 | 0.10 | 75.4 |

| 16 | 6.00 | 40.00 | 0.25 | 80.7 |

| 17 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 81.2 |

| 18 | 7.00 | 55.00 | 0.50 | 74.1 |

| 19 | 6.00 | 50.00 | 0.25 | 76.1 |

Fig. 2.

Contour map (a) and surface map (b) of the effect of pH, temperature and their reciprocal interactions on the solubility of YSP

Table 2.

ANOVA of solubility tests

| Source | Sum of squares | Degree of freedom | Mean square | F-value | P value; Prob > F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2458.63 | 9 | 273.18 | 20.79 | < 0.0001 | ** |

| A-pH | 343.70 | 1 | 343.70 | 26.15 | 0.0006 | ** |

| B-Temperature | 630.37 | 1 | 630.37 | 47.97 | < 0.0001 | ** |

| C-NaCl | 0.076 | 1 | 0.076 | 0.0058 | 0.9409 | |

| AB | 73.61 | 1 | 73.61 | 5.60 | 0.0421 | * |

| AC | 21.81 | 1 | 21.81 | 1.66 | 0.2298 | |

| BC | 20.77 | 1 | 20.77 | 1.58 | 0.2403 | |

| A2 | 189.08 | 1 | 189.08 | 14.39 | 0.0043 | ** |

| B2 | 354.02 | 1 | 354.02 | 26.94 | 0.0006 | ** |

| C2 | 208.39 | 1 | 208.39 | 15.86 | 0.0032 | ** |

| Residual | 118.27 | 9 | 13.14 | |||

| Lack of fit | 103.05 | 5 | 20.61 | 5.41 | 0.0634 | Not significant |

| Pure error | 15.23 | 4 | 3.81 | |||

| Cor total | 2576.91 | 18 |

**Means significant differences (P < 0.01)

*Means significant differences (P < 0.05)

In addition, the minimum solubility values at all temperatures were at pH 4, which was close to the isoelectric point of YSP, and the interaction between pH and NaCl concentration was the weakest near the isoelectric point. Furthermore, at pH 4, 5 and 6, the solubility decreased with increasing temperature, which indicated that the protein was denatured as the temperature rose. In the case of pH 4, increases in temperature will break the secondary and tertiary structures of a protein, in which the expanded bonds were beneficial to the interaction among the hydrophobic groups such that the initial solubility declined as the temperature increased (Dhg and Gasparetto 2005). At pH 4, the solubility was very low; in fact, the change in solubility with the temperature rise was not obvious; it only decreased slightly, and as shown by this model, the significance of temperature is slightly higher than that of pH. At pH 7 and 8, the solubility increased with temperature between 40 °C and 45 °C, indicating that the protein did not aggregate or solidify in this case.

Emulsifying activity of YSP

Emulsifying activity index (EAI) of YSP

Effects of interactions of different concentrations and pH on the EAI of YSP

Since the emulsifying activity depends on the formation of a stable interfacial protein film, emulsion formation should increase with the concentration of soluble protein (Shilpashree et al. 2015). In this study, EAI progressively increased with the YSP concentration (Fig. 3a). The increase in protein concentration promoted enhanced interaction between the oil phase and the aqueous phase. Before the isoelectric point (pH 3.5), the emulsifying activity of YSP increased with the pH. However, there was a transition around the isoelectric point, and the emulsifying activity of YSP decreased between pH 3.5 and 6. The electrostatic repulsion between molecules increased with the increasing hydroxide ions. Therefore, an increasing pH can enhance the repulsion among the protein molecules, and the emulsifying activity increased with the pH under the neutral or alkaline conditions. Based on these results, it is reasonable that the solubility of the protein should influence its emulsifying properties.

Fig. 3.

a EAI determined in 0.1% YSP (w/v, filled triangle), 0.3% YSP (w/v, filled rectangle), 0.5% YSP (w/v, filled diamond); b EAI determined in YSP solubilized in distilled water (filled diamond), 0.1% NaCl (w/v, filled rectangle), 0.3% NaCl (w/v, filled triangle), 0.5% NaCl (w/v, filled fork) (1%YSP, w/v); and c microphotographs for 25% v/v o/w emulsions at varying protein concentrations (left–right): (left) fresh emulsions (0 h), (right) emulsions stored for 1 h

Effects of interactions of different NaCl concentrations and pH on the EAI of YSP

As shown in Fig. 3b, after adding NaCl, the pH-EAI curve became gentler with the increasing pH. NaCl (0.1%, 0.3% and 0.5%) increased EAI compared to the samples without it at the initial stage (pH < 4), but afterwards, the EAI decreased as pH increased. At high pH and concentration, the EAI decreased. Because of the reduction in electrostatic repulsion between the proteins near their isoelectric point, aggregation was the highest at pH 3.5. It was speculated that larger aggregates would require a longer time to migrate and cannot be aligned very well with the oil–water interface, which would reduce EAI (Hosseini-Parvar et al. 2016). The high salt concentration and pH remarkably reduced the EAI (pH > 6) compared to the salt-free control. Since the increase in NaCl concentration and pH improved the solubility, and this increase in protein solubility reduced the rate of YSP transferring to the oil–water interface, the emulsifying activity of YSP was thereby reduced (Hosseini-Parvar et al. 2016).

Emulsion particle size distribution

Effects of concentration on the emulsion particle size distribution of YSP

The average particle size measurement (Z-Ave, at pH 7) of YSP emulsions decreased with increasing protein concentration (Table 3) because the high interfacial protein concentration encouraged emulsion droplet destruction and prevented its aggregation. According to the data processing system (DPS), the average particle sizes at the concentrations of 0.3% and 0.5% were insignificantly different from that at the concentration of 0.1%, whereas the rest of the concentrations were different at the significance level of 5%. The large average particle size of the emulsion containing 0.1% protein indicated that protein content may not be sufficient to cover the oil droplets and fully form a dense adsorption layer (Sánchez and Patino 2005). Consequently, the proteins acted as bridges among the oil droplets and led to droplet aggregation. In addition, the polydispersity index (PDI) increased as the protein concentration increased, and the distribution became more inhomogeneous (Table 3).

Table 3.

Z-Ave and polydispersity index (PDI) values at different protein concentrations, emulsion pH and NaCl concentrations

| Z-Ave (d.nm) | PDI | |

|---|---|---|

| Protein concentration (%) | ||

| 0.1 | 1674 ± 2.028a | 0.166 |

| 0.3 | 1662 ± 0.577ab | 0.256 |

| 0.5 | 1650 ± 0.577ab | 0.260 |

| 1.0 | 1629 ± 3.480b | 0.320 |

| 1.5 | 1556 ± 2.081c | 1.000 |

| 2.0 | 1495 ± 1.453d | 0.867 |

| 3.0 | 1082 ± 1.455e | 1.000 |

| Emulsion pH | ||

| 3 | 1778 ± 2.40a | 0.255 |

| 7 | 1342 ± 2.33b | 0.167 |

| 10 | 1235 ± 3.05c | 0.134 |

| NaCl concentration (%) | ||

| 0.0 | 1035 ± 1.73e | 0.065 |

| 0.1 | 1204 ± 2.88d | 0.142 |

| 0.3 | 1396 ± 2.08c | 0.157 |

| 0.5 | 1486 ± 1.53b | 0.257 |

| 1.0 | 1565 ± 1.20a | 1.000 |

All values are means of triplicate determinations ± SD. Means within columns with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Effects of different pH on the emulsion particle size distribution of YSP

When the protein concentration was 0.1%, the PDI value was the minimum, indicating that the protein distribution was the most uniform in this concentration (Table 3). Therefore, 0.1% protein concentration was set as the testing concentration. The average particle size and PDI of the emulsions at three different pH values (pH 3, 7 and 10) are shown in Table 3. The average droplet size was clearly reduced with the increasing pH (3–10) of the YSP emulsions. As the isoelectric point (pH 3.5) of YSP was approached, the emulsification of YSP was weaker, and many little droplets kept gathering to form large ones. Therefore, the average particle size value of YSP emulsion (Z-Ave) was largest at pH 3. Under alkaline conditions, due to the increase in hydroxide ions, the YSP emulsification was better; thus, the average particle size was smaller than the sizes in acidic and neutral solutions. Generally, the smaller the particle sizes of the emulsion were, the better the emulsifying ability of the protein was (Shen and Tang 2014). The PDI value was the maximum at pH 3, as its protein emulsification was poor, which caused its uneven distribution. In contrast, the PDI value was at its minimum at pH 10, which indicated that at this pH, the emulsifying property of the protein was better, and the distribution was uniform.

Effects of different NaCl concentrations on the emulsion particle size distribution of YSP

The emulsifying activity of YSP was sensitive to salt, as well, according to the particle size distribution. The particle size distribution of the emulsion was thoroughly changed by the addition of salt. To better elucidate the effects of NaCl concentration on the particle size distribution of YSP, the PDI values and Z-Aves at pH 7 were investigated (Table 3). The Z-Ave and PDI value significantly increased with the NaCl concentration, indicating that salt addition encouraged droplet aggregation. In addition, the increasing ionic strength reduced the net charge on the droplets and made the proteins tend to aggregate (solubility decrease); therefore, the emulsion was destabilized by flocculation. According to difference analysis, the Z-Aves of yam emulsions at different NaCl concentrations (0.0%, 0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5% and 1.0%) were significantly different at the 5% level.

Optical microscopy

The droplet size of YSP emulsions significantly decreased as protein concentration increased (Fig. 3c). Similar observations have been reported with stabilized emulsions of other kinds of proteins, such as whey protein isolates (Lizarraga et al. 2008). The average droplet size decreased as protein concentration increased, the main reason was that during the emulsification process, the average diameter of dispersed oil phase droplets was usually determined by the balance between the droplet rupture and coalescence. High interfacial protein concentrations promoted a drop rupture and prevented droplet coalescence, which led to smaller droplet size. The image results shown by microscope were consistent with those of the particle size analyzer (Table 3).

Conclusion

The protein concentration significantly influenced the solubility of YSP. According to the univariate analysis, the maximum solubility was obtained at pH 7, at 45 °C, and at 0.5 mol/L NaCl concentration, as well. In addition, the protein solubility decreased as the CaCl2 concentration increased. As the result of RSM, the solubility was affected by temperature, pH, and salt concentration individually and interactively. The interaction between pH and temperature on the solubility of YSP was highly significant. High NaCl concentration reduced the effect of pH on the emulsifying activity of YSP. As the pH increased, the average particle size of the YSP emulsion decreased, and the PDI value decreased, as well. The optimum conditions (the maximum solubility) were pH 7, temperature 40 °C and NaCl concentration 0.5 mol/L. In addition, the image analysis results of the emulsions were consistent with the results of the particle size analyzer. For the comprehensive utilization of yam resources, more targeted research studies should be conducted on the application of YSP in various food systems, such as beverage, bakery and sausage.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201285), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M611752), the Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program (XLYC1807270), the Serving Local Project of the Education Department of Liaoning Province, China (LFW201704) and the Science and Technology Support Program from Shenyang City (17136800).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Amarowicz R. Achievements and challenges in improving the nutritional quality of food legumes. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2015;34(1–3):105–143. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DL, Beames B, Summers MD, Park WD. Characterization of the lipid acyl hydrolase activity of the major potato (Solanum tuberosum) tuber protein, patatin, by cloning and abundant expression in a baculovirus vector. Biochem J. 1988;252(1):199–206. doi: 10.1042/bj2520199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu R, Sartie A. Crops that feed the World 1 Yams. Food Secur. 2010;2(4):305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra IC, Castro LAB, Neshich G, Almeida ERPD, Sá MFGD, Mello LV, Monte-Neshich DC. A corm-specific gene encodes tarin, a major globulin of taro (Colocasia esculenta L. Schott) Plant Mol Biol. 1995;28(1):137–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00042045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedermann F, Schneider H. Experimental binding energies in supramolecular complexes. Chem Rev. 2016;116(9):5216. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casella MLA, Whitaker JR. Stabilization of proteins by solvents. J Food Biochem. 1990;14:453–475. [Google Scholar]

- Dhg P, Gasparetto CA. Whey proteins solubility as function of temperature and pH. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2005;38(1):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ettoumi YL, Chibane M, Romero A. Emulsifying properties of legume proteins at acidic conditions: effect of protein concentration and ionic strength. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2015;66:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Feist P, Hummon AB. Proteomic challenges: sample preparation techniques for microgram-quantity protein analysis from biological samples. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):3537–3563. doi: 10.3390/ijms16023537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Wang XW, Jia YF, Zhang JW, Yu TY, Xue YL. Recent progress in yam storage protein dioscorin. Food Sci. 2014;35(11):299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Glusac J, Isascharovdat S, Kukavica B, Fishman A. Oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by tyrosinase-crosslinked potato protein. Food Res Int. 2017;100(1):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson A. Experimental methods for measuring coalescence during emulsification—a critical review. J Food Eng. 2016;178:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Henchion M, Hayes M, Mullen AM, Fenelon M, Tiwari B. Future protein supply and demand: strategies and factors influencing a sustainable equilibrium. Foods. 2017;6(7):53. doi: 10.3390/foods6070053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini-Parvar SH, Osano JP, Matia-Merino L. Emulsifying properties of basil seed gum: effect of ph and ionic strength. Food Hydrocolloids. 2016;52:838–847. [Google Scholar]

- Hou WC, Liu JS, Chen HJ, Chen TE, Chungfang Chang A, Lin YH. Dioscorin, the major tuber storage protein of yam (Dioscorea batatas decne) with carbonic anhydrase and trypsin inhibitor activities. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47(5):2168–2172. doi: 10.1021/jf980738o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu GJ, Zhao Y, Gao Q, Wang XW, Zhang JW, Peng X, Tanokura M. Functional properties of chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita, thunb. cv. baiyu) soluble protein. J Food Sci Technol. 2018;55(1):381–388. doi: 10.1007/s13197-017-2948-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YM, Lin KW. Antioxidative ability, dioscorin stability, and the quality of yam chips from various yam species as affected by processing method. J Food Sci. 2010;74(2):C118–C125. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Ru Q, Ding Y. Glycation a promising method for food protein modification: physicochemical properties and structure, a review. Food Res Int. 2012;49(1):170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lizarraga MS, Pan LG, AñOn MC, Santiago LG. Stability of concentrated emulsions measured by optical and rheological methods. Effect of processing conditions-I. Whey protein concentrate. Food Hydrocolloids. 2008;22(5):868–878. [Google Scholar]

- Ma F, Chen C, Sun G, Wang W, Fang H, Han Z. Effects of high pressure and CaCl2, on properties of salt-soluble meat protein gels containing locust bean gum. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2012;14(2):31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez CC, Patino JMR. Interfacial, foaming and emulsifying characteristics of sodium caseinate as influenced by protein concentration in solution. Food Hydrocolloids. 2005;19(3):407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Tang CH. Emulsifying properties of vicilins: dependence on the protein type and concentration. Food Hydrocolloids. 2014;36(2):278–286. [Google Scholar]

- Shilpashree BG, Arora S, Chawla P, Tomar SK. Effect of succinylation on physicochemical and functional properties of milk protein concentrate. Food Res Int. 2015;72(2):223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tsumura K, Saito T, Tsuge K, Ashida H, Kugimiya W, Inouye K. Functional properties of soy protein hydrolysates obtained by selective proteolysis. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2005;38(3):255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yu J, Gao W, Liu H, Xiao P. New starches from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)—Chinese yam (Dioscorea opposita, Thunb.) cultivars. Carbohyd Res. 2006;341(2):289–293. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Tang CH, Li BS, Yang XQ, Li L, Ma CY. Effects of high-pressure treatment on some physicochemical and functional properties of soy protein isolates. Food Hydrocolloids. 2008;22(4):560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZC, Tian WH, Cui SW, Zhao XW, Zheng JQ, Chang W, Yuan DQ. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on the solubility and molecular structure of rice protein. Chin J High Press Phys. 2013;27(4):609–615. [Google Scholar]

- Xue YL, Miyakawa T, Sawanoa Y, Tanokura M. Cloning of genes and enzymatic characterizations of novel dioscorin isoforms from Dioscorea japonica. Plant Sci. 2012;183(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue YL, Miyakawa T, Nakamura A, Hatano KI, Sawano Y, Tanokura M. Yam tuber storage protein reduces plant oxidants using the coupled reactions as carbonic anhydrase and dehydroascorbate reductase. Mol Plant. 2015;8(7):1115–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuliana M, Chi TT, Huynh LH, Ho QP, Ju YH. Isolation and characterization of protein isolated from defatted cashew nut shell: influence of pH and NaCl on solubility and functional properties. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2014;55(2):621–626. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Liu P, Wang Y, Gao W. Study on physico-chemical properties of dialdehyde yam starch with different aldehyde group contents. Thermochim Acta. 2011;512(1–2):196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. Protein stabilization and enzyme activation in ionic liquids: specific ion effects. J Chem Technol Biotechnol. 2016;91(1):25. doi: 10.1002/jctb.4837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Gao Q, Wang XW, Jia YF, Zhang JW, Ai XZ, Xue YL. Response surface test optimization of alkali soluble acid precipitation method for extraction of yam storage protein. Food Sci. 2015;36(16):7–11. [Google Scholar]