Abstract

The restricted availability, expense and toxicity of precious metal catalysts such as rhodium and palladium challenge the sustainability of synthetic chemistry. As such, nickel catalysts have garnered increasing attention as replacements for enyne cyclization reactions. On the other hand, bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes are found as core structures in many biologically active natural products; however, the synthesis of such frameworks with high functionalities from readily available precursors remains a significant challenge. Herein, we report a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric domino cyclization reaction of enynones, providing rapid and modular synthesis of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane skeletons with three quaternary stereocenters in good yields and remarkable high levels of regio- and enantioselectivities (92–99% ee).

Subject terms: Asymmetric catalysis, Homogeneous catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes are often found in bioactive natural products; however, their synthesis poses significant challenges. Here, the authors report a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric domino cyclization of enynones, providing a rapid and modular synthesis of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane skeletons.

Introduction

With the growing concerns about environmental sustainability, the development of elegant methodologies for efficient and concise synthesis of complex bioactive natural and pharmaceutical products in a step-, atom- and redox-economic manner has received widespread attention. One of the most effective approaches to achieve such a goal is to develop catalytic asymmetric domino reactions in which multiple bond-making events occur in one-pot, and complex chiral compounds with multi-stereogenic centers are generated from easily accessible precursors1,2. Consequently, significant efforts have been directed towards the development of asymmetric domino reactions, where the focus has been on the efficient synthesis of biologically important and highly functionalized chiral carbo- and heterocyclic compounds. In this context, the bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes are found as core structures in many bioactive natural products, including Schincalide A3 and Illisimonin A4 (Fig. 1). Despite their importance, the bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane remain an elusive skeleton, and the development of which has been clearly underexploited5–7. Only recently, Rychnovsky’s group reported the first total synthesis of Illisimonin A, in which the key tricyclic core was constructed by Diels-Alder reaction, and enantioselective control of this transformation has not yet been achieved8. The limited output for these challenging molecules may be due to the difficulty in asymmetric synthesis of the bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane core9–12, which hinders any further study on their potential bioactive properties. Therefore, a general approach that enables the modular and enantioselective synthesis of this key skeleton is highly desired and sought-after.

Fig. 1. Representative examples of bioactive compounds.

Bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane scaffolds are structural cores in many natural products.

Transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric domino cyclization of 1,n-enynes represents a powerful synthetic tool to rapidly assemble chiral carbo- and heterocyclic compounds. Traditionally used precious metal catalysts based on Rh, Ir, and Pd, etc., have been widely used in such transformations13–25. However, they are very expensive and their reserves are declining, thus limiting their wide-scale industrial applications. As such, increasing attention has been focused on the development and use of earth-abundant and sustainable element, especially nickel catalysts, to replace these highly expensive and scarce metals in 1,n-enyne cyclization. However, the reaction is typically restricted to the use of activated alkenes, and the regioselectivity is controlled by the formation of a five-membered ring nickelacyclic intermediate26,27 (Fig. 2a). Recently, Lam et al. developed Ni-catalyzed asymmetric coupling cyclization of aryl-substituted alkynes with ketones28 (Fig. 2b). We envisioned that the introduction of a 1,3-cyclopentanedione functionality on the 1,6-enyne moiety might facilitate a domino arylnickelation of alkyne/Heck cyclization with alkene/nucleophilic addition to ketone sequence, and therefore provides an expedient access to biologically important bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5] decanes (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2. Reaction design.

a Ni-catalyzed coupling cyclization of an alkyne and an activated alkene; b Ni-catalyzed asymmetric coupling cyclization of an alkyne and a ketone; c Working hypothesis for bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes synthesis via coupling cyclization of an alkyne, an alkene and a ketone.

However, to realize the above conceptually simple yet attractive reaction, many challenging problems need to be addressed. The first is to control the regioselectivity of the 1,2-addition of the arylnickel species to the alkyne moiety29–33. since the regioselectivity we expected is contrary to that reported by Lam28. The second is to control the enantioselectivity of the Heck-cyclization process. Another challenge is that ketones are more electrophilic than unactivated alkenes, the direct cyclization of alkynes and ketones may take place preferentially, while unactivated alkenes do not participate in the cyclization process34–50.

Herein, we report catalytic enantioselective construction of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes with multiple quaternary stereocenters by Ni-catalyzed domino coupling cyclization of an alkyne, an alkene and a ketone in a highly regio- and enantioselective fashion. This domino strategy not only has the advantage of being efficient, simple and starting from easily accessible precursors, but also provides the desired targets with two additional functional sites (a ketone and a fully substituted double bond), which could be easily used for diversity-oriented synthesis. This work documents a practical, catalytic enantioselective (92–99% ee) approach to the most diverse set of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes reported to-date.

Results

Reaction development

According to the reaction design shown in Fig. 2c, we began with an investigation of the model reaction for the construction of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes using the 1,3-cyclopentanedione tethered 1,6-enyne 1a as substrate, which can be easily prepared by a two-step sequence consisting of the reductive Knoevenagel condensation of commercially available cyclopentane-1,3-dione with alkynals51,52 followed by allylation with allyl halides. The reaction was first conducted with 10 mol % of Ni(OAc)2.4H2O and 12 mol % of (S)-phenyl-Phox (L1) as catalyst in MeCN. As anticipated, the cyclization of 1a to 4aa (60%) was the major product of the reaction28, in which unactivated alkene was not involved, and only trace amount of the desired 3aa could be observed (Table 1, entry 1). The formation of 4aa could not be mitigated and remained the main reaction pathway by using MeOH, DMF or toluene as solvent (Table 1, entries 2–4), which reinforces the notion that the domino cyclization of 1a to bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane 3aa would be far from trivial.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditionsa.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Solvent | Yield of 4aa (%)b | Yield of 3aa (%)b | ee of 3aa (%)c |

| 1 | L1 | MeCN | 60 | Trace | – |

| 2 | L1 | MeOH | 54 | Trace | – |

| 3 | L1 | DMF | 12 | Trace | – |

| 4 | L1 | Toluene | 5 | Trace | – |

| 5 | L1 | TFE | 12 | 33 | 71 |

| 6 | L2 | TFE | Trace | 41 | 65 |

| 7 | L3 | TFE | 12 | 42 | 76 |

| 8 | L4 | TFE | 9 | 46 | 75 |

| 9 | L5 | TFE | 24 | 26 | 60 |

| 10 | L6 | TFE | 20 | Trace | – |

| 11 | L7 | TFE | Trace | 12 | 25 |

| 12 | L8 | TFE | Trace | Trace | – |

| 13 | L9 | TFE | 37 | Trace | – |

| 14 | L10 | TFE | <1 | 77 | 98 |

TFE 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol.

aReaction condition: 1a (0.1 mmol), 2a (2 equiv), Ni(OAc)2.4H2O (0.1 equiv), ligand (0.12 equiv), TFE (1 mL) at 100 °C for 48 h.

byields of isolated products.

cDetermined by HPLC on a chiral stationary phase.

To suppress the formation of undesired 4aa, it is necessary to activate the double bond. Interestingly, the desired product 3aa was afforded in 33% yield and 71% ee when the reaction was performed in TFE as solvent (Table 1, entry 5). Subsequently, different chiral Phox-type ligands L2-L4 were screened, the yields and ee values of 3aa remained moderate (Table 1, entries 6–8). To further improve the yield and enantioselectivity, various bidentate phosphine ligands such as (S)-BINAP (L5), (S)-SegPhos (L6), (S,S)-Me-DuPhos (L7), (S,S)-Ph-BPE (L8) and (R,S)-Ming-Phos (L9) were investigated. Unfortunately, neither the yields nor the enantioselectivities were improved (Table 1, entries 9–13). Excitingly, 3aa was obtained in 77% yield and 98% ee when a conformationally rigid P-stereogenic bis(phospholane) ligand L10 (1 R,1’R,2 S,2’S-Duanphos)53 was used (Table 1, entry 14).

The E/Z configuration of the double bond and the absolute configuration of three newly formed quaternary stereocenters in 3aa were unambiguously assigned by X-ray crystal crystallography (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Absolute configuration.

ORTEP representation of the product 3aa.

Substrate scope

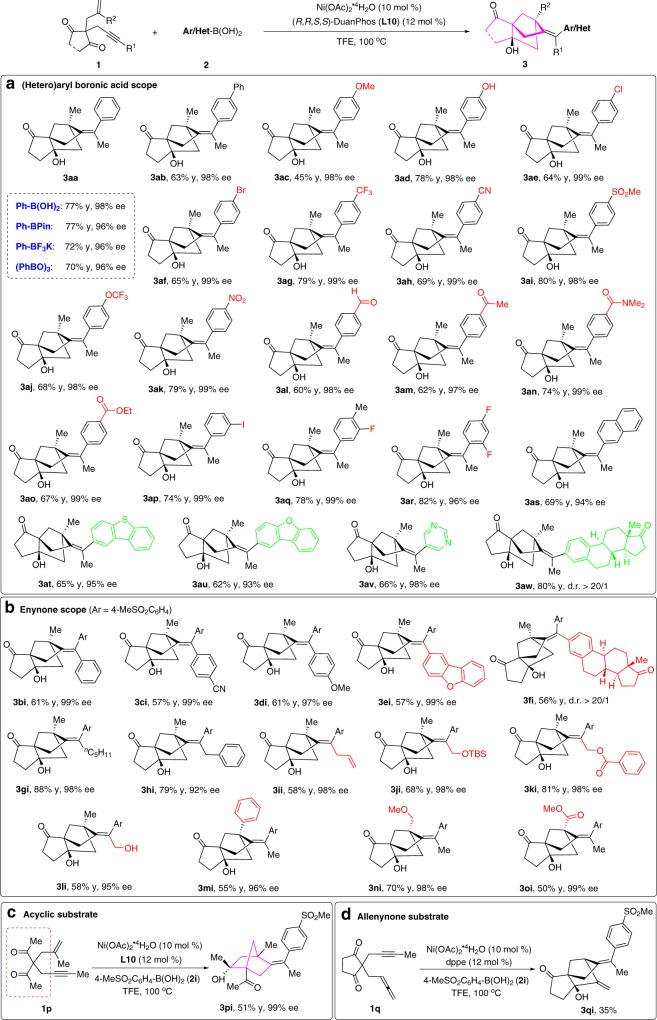

With optimal reaction conditions in hand, we first investigated the effect of various aryl-boron reagents, such as PhB(OH)2, PhBPin (phenylboronic acid pinacol ester), PhBF3K and (PhBO)3 (phenylboroxine) (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, all these aryl-boron reagents are compatible. Among them, the Ph-B(OH)2 performed best comprehensively. The compatibility of the transformation with various (hetero)arylboronic acids was then evaluated in a robustness screening. A variety of para-substituted arylboronic acids could undergo tandem cyclization to provide the target bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes 3aa-3ao in 45–80% yields and 97–99% ee. All of these meta- and ortho-substituted arylboronic acids proceeded smoothly, providing the corresponding products 3ap-3ar in 74–82% yields and 96–99% ee. Notably, a series of synthetic valuable functional groups such as ether (3ac), free hydroxyl (3ad), chloride (3ae), bromide (3af), trifluoromethyl (3ag), cyano (3ah), sulfonyl (3ai), trifluoromethoxyl (3aj), nitro (3ak), aldehyde (3al), ketone (3am), amide (3an), ester (3ao), iodide (3ap) and fluoride (3aq and 3ar) were all well-tolerated. In addition, various (hetero)arylboronic acids was also investigated. Naphthalene (3as), dibenzothiophene (3at) and dibenzofuran (3au) were successfully incorporated into the desired products in 62–69% yields and 93–95% ee. Remarkably, pyrimidine was perfectly accommodated to furnish 3av in 66% yield with 98% ee, which exhibits a wide variety of biological activities54. Another interesting feature is that estrone could also be engaged in this route to afford the desired product 3aw in good yield and high diastereoselectivity (80% yield, >20/1 d.r.), thus demonstrating the robustness and generality of this methodology for the modification of complex biologically active molecules. However, no reaction was observed using an alkyl or alkenyl boronic acids.

Fig. 4. Substrate scope.

a (Hetero)arylboronic acid scope. b Enynone scope. c Acyclic substrate. d Allenynone substrate.

Next, the substrate scope of enynone 1 was explored in reactions with (4-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl)boronic acid 2i, which furnished products 3bi-3oi in synthetic useful yields and 92–99% ee (Fig. 4b). We first studied the influence of the substituents at the alkyne terminus (R1). The aryl group having an electron-donating or electron-withdrawing group at the alkyne terminus was found to be compatible, leading to the corresponding products 3bi-3di in 57-61% yields and 97–99% ee. A dibenzofuran substituent which is very useful structural unit in organofunctional materials, could be successfully incorporated into the product 3ei (57% yield, 99% ee). Moreover, estrone substituted substrate could also be employed in this type of reaction sequence to provide the desired 3fi in high diastereoselectivity (>20/1 d.r.). The reaction is not limited to aryl group at the alkyne terminus, and alkyl-substituted alkynes such as n-pentyl, benzyl, allyl and those functionalized with CH2OTBS and CH2OBz were also suitable substrates. It is noteworthy that 1 l bearing a free hydroxyl group could be efficiently converted to 3li in 58% yield with 95% ee. However, terminal alkyne provides complex mixtures of unidentified products. Then, we investigated the influence of substituents on the alkene moiety (R2). The introduction of a phenyl group at C2 of the propene moiety did not preclude the transformation, producing 3 mi in 55% yield with 96% ee. A methoxymethyl group was performed uniformly to give 3ni in 70% yield and 98% ee at this position. Interestingly, substrate 1o bearing an ester group on the double bond was also amenable to this transformation, giving the desired 3oi in outstanding enantioselectivity (99% ee).

This transformation is not restricted to cyclic 1,3-diketone tethers, as substrate 1p containing acyclic 1,3-diketone tethered 1,6-enyne is also highly effective. As shown in Fig. 4c, the highly functionalized bicyclo[2,2,1]heptane derivative 3pi bearing three quaternary stereocenters could also be efficiently constructed in 99% ee. It is worth noting that this bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane ring system is also a very important skeleton found in many pharmacologically active molecules55–57.

We further prepared 1,3-cyclopentanedione tethered 1,6-diene substrate, however, the expected product was not obtained. Interestingly, substrate 1q possessing allenyne tether could undergo an analogous cyclization reaction to afford the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane 3qi (Fig. 4d).

Synthetic applications

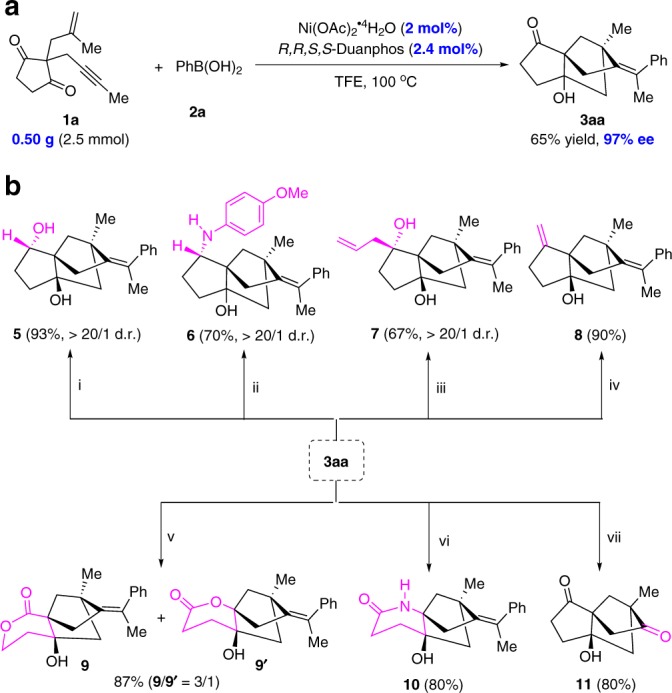

We carried out a 0.5 g scale reaction of 1a and found that the chiral Ni-catalyst loading as low as 2.0 mol % was sufficient to provide 3aa in 65% yield with 97% ee, thus revealing the practical applicability of this Ni-catalyzed domino reaction (Fig. 5). To further demonstrate the synthetic benefit of our domino cyclization, Post-modifications on the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane skeleton were performed (Fig. 5). Compound 3aa could undergo a diastereoselective reduction by NaBH4 to form the corresponding alcohol 5 in 93% yield. Under reductive amination conditions with NaBH(OAc)3 and 4-methoxyaniline, 3aa was converted into amine 6 in 70% yield with >20/1 diastereoselectivity. A further diastereoselective 1,2-addition of allylMgBr to 3aa afforded the allyl alcohol 7 in 67% yield. Moreover, olefination of the ketone moiety of 3aa with PPh3MeBr via the Wittig reaction gave a new alkene 8 in 90% yield. We further took advantage of the ketone moiety to generate the bridged tricyclic lactones 9 and 9’ with a ratio of 3:1 through the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation in the presence of m-CPBA. Interestingly, bridged tricyclic lactam 10 could also be selectively obtained in 80% yield via the Schmidt reaction with NaN3. Finally, the tetrasubstituted double bond was cleaved by ozonolysis with O3 to give optically pure tricyclic diketone 11 in 80% yield.

Fig. 5. Half-gram scale reaction and synthetic manipulations.

a Half-gram scale reaction. b Synthetic applications. (i) NaBH4, EtOH, 0 °C~ rt; (ii) 4-methoxyaniline (3 equiv), NaBH3CN, MeOH, rt; (iii) allylMgBr, THF, −78 °C-rt; (iv) PPh3MeBr, tBuOK, THF, 0 °C-rt; (v) m-CPBA, NaHCO3, DCM, rt; (vi) NaN3, TFA/H2O = 4/1, 70 °C; (vii) O3/PPh3, DCM, −78 °C-rt. m-CPBA m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid, TFA trifluoroacetic acid.

Mechanistic investigation

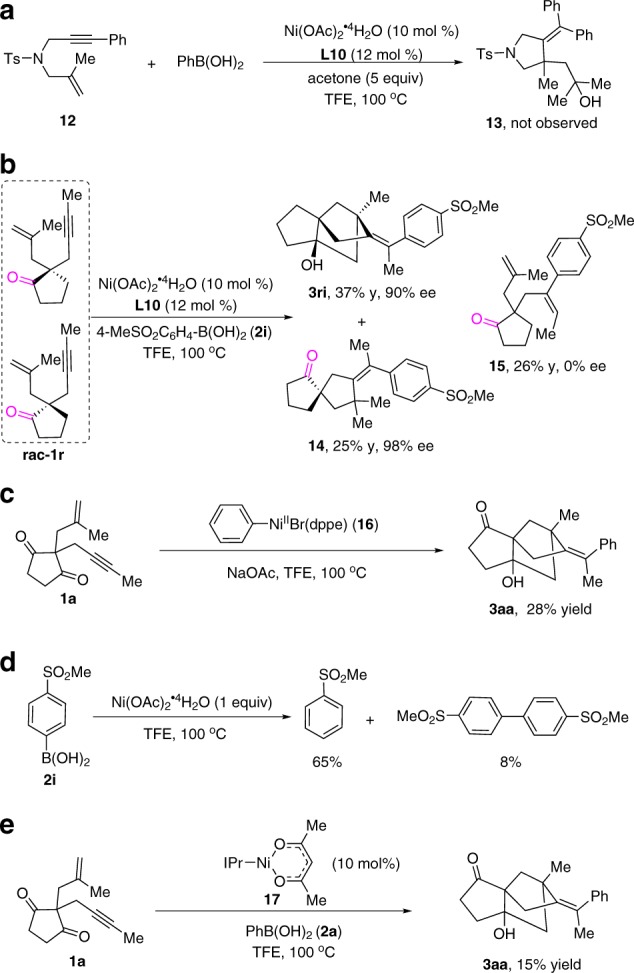

We conducted preliminary mechanistic experiments to provide insight about the reaction mechanism. The reaction of enyne 12 with PhB(OH)2 in the presence of acetone resulted in a complex of mixture, the expected product 13 formed through enyne cyclization/intermolecular nucleophilic addition to acetone, was not observed (Fig. 6a). In addition, the reaction of mono-carbonyl enyne 1r under our standard reaction conditions led to the formation of significant amount of the regioisomeric arylation product 15 (26% yield, Fig. 6b). These results indicate that these two ketone carbonyl groups on the substrate are very crucial. No enantiomeric excess was detected for product 15, suggesting that the 1,2-addition of arylnickel species to alkyne might not be the turnover-limiting step. The formation of product 3ri and 14 was likely a kinetic resolution process, where one of the enantiomer of racemic 1r was transformed to the 3ri in 37% yield with 90% ee, while the other was converted to 14 in 25% yield with 98% ee. These results clearly demonstrate that the Heck-cyclization process is the enantioselective-determining step of this transformation.

Fig. 6. Mechanistic studies.

a Three-component reaction with acetone. b The domino reaction used mono-carbonyl enyne substrate. c The use of stoichiometric aryl-Ni(II) complex in the reaction. d The stoichiometric reaction of Ni(OAc)2.4H2O with boronic acid. e The use of Ni(I) complex in the reaction.

In order to further understand the reaction mechanism and catalytically active species of this transformation, aryl-Ni(II) complex 16 was prepared6,58,59, and the stoichiometric reaction of 16 with 1a afforded 3aa in 28% yield (Fig. 6c), implying that aryl-Ni(II) species is involved in the catalytic cycle. We performed a stoichiometric reaction of Ni(OAc)2.4H2O (1 equiv) and 2i (1 equiv) in TFE, it was found that in addition to a deboronated product (65%), a biaryl product was also detected (Fig. 6d). This result indicates that Ni(II) was reduced to Ni(0) by reductive elimination of the corresponding diarylnickel(II) intermediate. Therefore, Ni(I) species may be generated by the disproportionation reaction between Ni(II) and Ni(0) species. IPrNi(acac) 17 was synthesized following the previously reported procedure60. This Ni(I) complex was also found to catalyze the domino cyclization of 1a with PhB(OH)2 to afford 3aa (Fig. 6e), thus indicating that an alternative mechanism involving aryl-Ni(I) species cannot be ruled out.

Proposed reaction mechanism

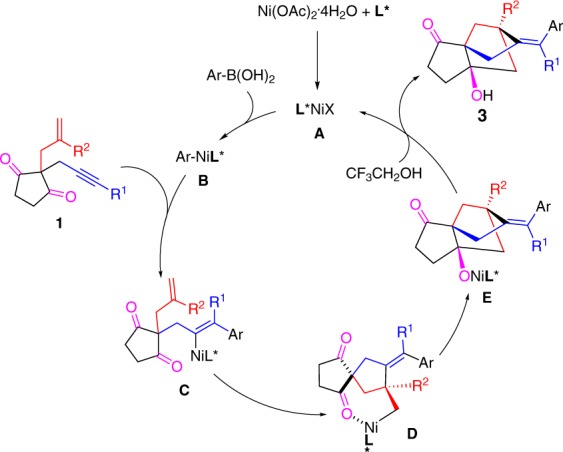

On the basis of the above results, a possible catalytic cycle for this transformation is proposed in Fig. 7. Transmetallation of arylboronic acid with the chiral nickel species A (X could be acetate, hydroxide or 2,2,2-trifluoroethoxide) gives the arylnickel complex B. The 1,2-addition of arylnickel species to the triple bond to form an alkenylnickel intermediate C. An intramolecular migratory insertion of alkenylnickel C into double bond affords the σ-alkylnickel intermediate D61–64. A subsequent nucleophilic cyclization of the resulting σ-alkylnickel species D onto one of the ketones leads to nickel alkoxide species E, followed by protonolysis to regenerate the catalytical active nickel catalyst and release the desired tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane product 3. The oxidation state of nickel catalyst is still unclear, both Ni(I) and Ni(II) are possible.

Fig. 7. Reaction mechanism.

Proposed catalytic cycle.

Discussion

In summary, a nickel-catalyzed asymmetric domino cyclization of 1,3-diketone tethered 1,6-enynes has been successfully developed, providing a general synthesis of optically pure bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes with three quaternary stereocenters in good yields and remarkable high levels of enantioselectivities (92–99% ee). This reaction is initiated by a regioselective 1,2-addition of arylboronic acid to the alkyne, followed by an enantioselective Heck-cyclization with unactivated alkene and nucleophilic cyclization of the resulting σ-alkylnickel species to the ketone group. Preliminary mechanistic studies indicate that either Ni(I) or Ni(II) species may be involved in the catalytic cycle.

Methods

Procedure for enantioselective synthesis of bridged tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decanes

To an oven-dried sealed tube equipped with a PTFE-coated stir bar was charged with Ni(OAc)2.4H2O (0.01 mmol, 10 mol %), 1 R,1’R,2 S,2’S-Duanphos (0.012 mmol, 12 mol %) and TFE (1 mL). This reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 minutes in an argon-filled glovebox. Enynone 1 (0.1 mmol) and (hetero)arylboronic acid 2 (0.2 mmol, 2 equiv) was then added. The sealed tube was sealed and removed from the glovebox. Then the mixture was stirred at 100 °C until the reaction was complete (monitored by TLC). The resulting mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified by column chromatography on silica gel, eluting with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 5/1~1/1 (v/v) to afford the corresponding product 3.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank to Prof. J. Zhu (Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne) for their helpful discussion. This work was supported by NSFC (21702149), “1000-Youth Talents Plan”, Wuhan University and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042018kf0012).

Author contributions

W.K. conceived and designed the project. W.K. and J.C. designed the experiments. J.C., Z.D., and Y.W. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. W.K. prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this work are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1963288 (3aa). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Rambabu Chegondi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-15837-1.

References

- 1.Xu, P. F. & Wang, W. Catalytic Cascade Reactions (Wiley-VCH, 2013).

- 2.Tietze, L. F. Multicomponent Domino Process: Rational Design and Serendipity (Wiley-VCH, 2014).

- 3.Zhou M, Liu Y, Song J, Peng X, Cheng Q, Cao H, Xiang M, Ruan H-L, Schincalide A. a schinortriterpenoid with a tricyclo[5.2.1.01,6]decane-bridged system from the stems and leaves of Schisandra incarnate. Org. Lett. 2016;18:4558–4561. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma S, Li M, Lin M, Li L, Liu Y, Qu J, Li Y, Wang X, Wang R, Xu S, Hou Q, Yu S, Illisimonin A. a caged sesquiterpenoid with a tricyclo[5.2.1.01,6]decane skeleton from the Fruits of Illicium simonsii. Org. Lett. 2019;19:6160–6163. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ihara M, Fukumoto K. Syntheses of polycyclic natural products employing the intramolecular double michael reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1993;32:1010–1022. doi: 10.1002/anie.199310101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ihara M, Makita K, Takasu K. Facile construction of the tricyclo[5.2.1.01,5]decane ring system by intramolecular double michael Reaction: highly stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-8,14-cedranediol and (±)-8,14-cedranoxide. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1259–1264. doi: 10.1021/jo981996n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takasu K, Mizutani S, Noguchi M, Makita K, Ihara M. Stereocontrolled total synthesis of (±)-culmorin via the intramolecular double michael Addition. Org. Lett. 1999;1:391–394. doi: 10.1021/ol9900562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns AS, Rychnovsky SD. Total synthesis and structure revision of (-)-illisimonin A, a neuroprotective sesquiterpenoid from the fruits of Illicium simonsii. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13295–13330. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b05065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamison TF, Shambayati S, Crowe WE, Schreiber SL. Cobalt-mediated total synthesis of (+)-epoxydictymene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5505–5506. doi: 10.1021/ja00091a079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seiple IB, Su S, Young IS, Lewis CA, Yamaguchi J, Baran PS. Total synthesis of palau’amine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:1095–1098. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pronin SV, Shenvi RA. Synthesis of highly strained terpenes by non-stop tail-to-head polycyclization. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:915–920. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu P, Snyder SA. Enantiospecific total synthesis of the highly strained (−)-presilphiperfolan-8-ol via a Pd-catalyzed tandem cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5007–5010. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen W-W, Xu M-H. Recent advances in rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of heterocycles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:1029–1050. doi: 10.1039/C6OB02021F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao P, Zhang X. The first highly enantioselective Rh-catalyzed enyne cycloisomerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:4104–4106. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4104::AID-ANIE4104>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei A, He M, Zhang X. Highly enantioselective syntheses of functionalized α-methylene-γ-butyrolactones via Rh(I)-catalyzed intramolecular alder ene reaction: application to formal synthesis of (+)-pilocarpine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8198–8199. doi: 10.1021/ja020052j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JH, Kim SM, Chung YK. Rh-catalyzed reductive cyclization of enynes using ethanol as a source of hydrogen. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:10852–10856. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen K, Han X, Lu X. Cationic Pd(II)-catalyzed highly enantioselective arylative cyclization of alkyne-tethered enals or enones initiated by carbopalladation of alkynes with arylboronic acids. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1756–1759. doi: 10.1021/ol3003546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Z, Tian B, Fukui Y, Tong X, Tian P, Lin G-Q. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric arylative cyclization of meso-1,6-dienynes leading to enantioenriched cis-hydrobenzofurans. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:5314–5318. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keilitz J, Newman SG, Lautens M. Enantioselective Rh-catalyzed domino transformations of alkynylcyclohexadienones with organoboron reagents.Org. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1148–1151. doi: 10.1021/ol400363f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masutomi K, Noguchi K, Tanaka K. Enantioselective cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes to bicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes catalyzed by rhodium and benzoic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:7627–7630. doi: 10.1021/ja504048u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trost BM, Ryan MC, Rao M, Markovic TZ. Construction of enantioenriched [3.1.0] bicycles via a ruthenium-catalyzed asymmetric redox bicycloisomerization reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17422–17425. doi: 10.1021/ja510968h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serpier F, Flamme B, Brayer J, Folleas B, Darses S. Chiral pyrrolidines and piperidines from enantioselective rhodium-catalyzed cascade arylative cyclization. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1720–1723. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng X, Ni S, Han Z, Guan Y, Lv H, Dang L, Zhang X-M. Enantioselective rhodium-catalyzed cycloisomerization of (E)-1,6-enynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:6295–6299. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oonishi Y, Masusaki S, Sakamoto S, Sato Y. Rhodium(I)-catalyzed enantioselective cyclization of enynes by intramolecular cleavage of the Rh-C bond by a tethered hydroxy group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:8736–8379. doi: 10.1002/anie.201902832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selmani A, Darses S. Access to chiral cyano-containing five-membered rings through enantioconvergent rhodium-catalyzed cascade cyclization of a diastereoisomeric E/Z mixture of 1,6-enynes. Org. Chem. Front. 2019;6:3978–3982. doi: 10.1039/C9QO01264H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery J. Nickel-catalyzed cyclizations, couplings, and cycloadditions involving three reactive components. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:467–473. doi: 10.1021/ar990095d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montgomery J. Nickel-catalyzed reductive cyclizations and couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3890–3908. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke C, Incerti-Pradillos CA, Lam HW. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed anti-carbometallative cyclizations of alkynyl electrophiles enabled by reversible alkenylnickel E/Z isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8068–8071. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lautens M, Mancuso J. Formation of homoallyl stannanes via palladium-catalyzed stannylative cyclization of enynes. Org. Lett. 2000;2:671–673. doi: 10.1021/ol005508l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marco-Martínez J, López-Carrillo V, Buñuel E, Simancas R, Cárdenas DJ. Pd-catalyzed borylative cyclization of 1,6-enynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1874–1875. doi: 10.1021/ja0685598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C, Mannathan S, Cheng C-H. Nickel-catalyzed chemo- and stereoselective alkenylative cyclization of 1,6-enynes with alkenyl boronic acids. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:12212–12216. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabrera-Lobera N, Rodríguez-Salamanca P, Nieto-Carmona JC, Buñuel E, Cárdenas DJ. Iron-catalyzed hydroborylative cyclization of 1,6-enynes. Chem. Eur. J. 2018;24:784–788. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh J-C, Hong Y-C, Yang C-M, Mannathan S, Cheng C-H. Nickel-catalyzed highly chemo- and stereoselective borylative cyclization of 1,6-enynes with bis(pinacolato)diboron. Org. Chem. Front. 2017;4:1615–1619. doi: 10.1039/C7QO00321H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moslin RM, Miller-Moslin K, Jamison TF. Regioselectivity and enantioselectivity in nickel-catalysed reductive coupling reactions of alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2007;2007:4441–4449. doi: 10.1039/b707737h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miura T, Murakami M. Formation of carbocycles through sequential carborhodation triggered by addition of organoborons. Chem. Commun. 2007;2007:217–224. doi: 10.1039/B609991B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iida H, Krische MJ. Catalytic reductive coupling of alkenes and alkynes to carbonyl compounds and imines mediated by hydrogen. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007;279:77–104. doi: 10.1007/128_2007_122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skucas E, Ngai M-Y, Komanduri V, Krische MJ. Enantiomerically enriched allylic alcohols and allylic amines via C–C bond-forming hydrogenation: asymmetric carbonyl and imine vinylation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1394–1401. doi: 10.1021/ar7001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeganmohan M, Cheng C-H. Cobalt- and nickel-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective reductive coupling of alkynes, allenes, and alkenes with alkenes. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:10876–10886. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malik, H. A., Baxter, R. D. & Montgomery, J. in Catalysis Without Precious Metals (ed. Bullock, R. M.) 181 (Wiley-VCH, 2010).

- 40.Tian P, Dong H, Lin G-Q. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric arylation. ACS Catal. 2012;2:95–119. doi: 10.1021/cs200562n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson EP, et al. Mechanistic basis for regioselection and regiodivergence in nickel-catalyzed reductive couplings. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1736–1745. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Standley EA, Tasker SZ, Jensen KL, Jamison TF. Nickel catalysis: synergy between method development and total synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1503–1514. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song J, Shen Q, Xu F, Lu X. Cationic Pd(II)-catalyzed enantioselective cyclization of aroylmethyl 2-alkynoates initiated by carbopalladation of alkynes with arylboronic acids. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2947–2950. doi: 10.1021/ol0711772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han X, Lu X. Control of chemoselectivity by counteranions of cationic palladium complexes: a convenient enantioselective synthesis of dihydrocoumarins. Org. Lett. 2010;12:108–111. doi: 10.1021/ol902538n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, Xu M-H. Rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric tandem cyclization for efficient and rapid access to underexplored heterocyclic tertiary allylic alcohols containing a tetrasubstituted olefin. Org. Lett. 2014;16:2712–2715. doi: 10.1021/ol500993h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson T, Choo K-L, Lautens M. Rhodium-catalyzed arylative cyclization for the enantioselective synthesis of (trifluoromethyl) cyclobutanols. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:14194–14197. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu W, Nie M, Wang A, Cao Z, Tang W. Highly enantioselective nickel-catalyzed intramolecular reductive cyclization of alkynones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:2520–2524. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan J, Yoshikai N. Cobalt-catalyzed arylative cyclization of acetylenic esters and ketones with arylzinc reagents through 1,4-cobalt migration. ACS Catal. 2016;6:3738–3742. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.6b01039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karad SN, Panchal H, Clarke C, Lewis W, Lam HW. Enantioselective synthesis of chiral cyclopent-2-enones by nickel-catalyzed desymmetrization of malonate esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:9122–9125. doi: 10.1002/anie.201805578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selmani A, Darses S. Enantioenriched 1-tetralones via rhodium-catalyzed arylative cascade desymmetrization/acylation of alkynylmalonates. Org. Lett. 2019;21:8122–8126. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramachary DB, Kishor M. Direct amino acid-catalyzed cascade biomimetic reductive alkylations: application to the asymmetric synthesis of Hajos-Parrish ketone analogues.Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:4176–4187. doi: 10.1039/b807999d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cuadros S, Dell’Amico L, Melchiorre P. Forging fluorine-containing quaternary stereocenters by a light-driven organocatalytic aldol desymmetrization process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:11875–11879. doi: 10.1002/anie.201706763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu D, Zhang X. Practical P-chiral phosphane ligand for Rh-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005;2005:646–649. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200400690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu, X.-F. & Wang, Z.-C. Transition Metal Catalyzed Pyrimidine, Pyrazine, Pyridazine and Triazine Synthesis 1st edn (Elsevier, 2017).

- 55.Tsuri T, et al. Bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane and 6,6-dimethylbicyclo[3.1.1]heptane derivatives: orally active, potent, and selective prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:3504–3507. doi: 10.1021/jm970343g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mitsumori S. Synthesis and biological activity of various derivatives of a novel class of potent, selective, and orally active prostaglandin D2 receptor antagonists. 1. bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:2436–2445. doi: 10.1021/jm020517g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohno M. Nucleotide analogues containing 2-oxa-bicyclo[2.2.1]heptane and l-α-threofuranosyl ring systems: interactions with P2Y receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:5619–5630. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Traina CA, Bakus RC, Bazan GC. Rhodium-catalyzed anti-markovnikov intermolecular hydroalkoxylation of terminal acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:32–34. doi: 10.1021/ja202877q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Senkovskyy V. “hairy” poly(3-hexylthiophene) particles prepared via surface-initiated kumada catalyst-transfer polycondensation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16445–16453. doi: 10.1021/ja904885w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X, Xie X, Liu Y. Nickel-catalyzed cyclization of alkyne-nitriles with organoboronic acids involving anti-carbometalation of alkynes. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:5815–5820. doi: 10.1039/C6SC01191H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ping Y, Li Y, Zhu J, Kong W. Construction of quaternary stereocenters by palladium-catalyzed carbopalladation-initiated cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:1562–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.201806088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang K, Ding Z, Zhou Z, Kong W. Ni-catalyzed enantioselective reductive diarylation of activated alkenes by domino cyclization/cross-couplin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:12364–12368. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b08190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ping Y. Ni-catalyzed regio- and enantioselective domino reductive cyclization: one-pot synthesis of 2,3-fused cyclopentannulated indolinesg. ACS Catal. 2019;9:7335–7342. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b02081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qin X, Lee MWY, Zhou JS. Nickel-catalyzed asymmetric reductive Heck cyclization of aryl halides to afford indolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:12723–12726. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this work are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding author upon request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1963288 (3aa). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.