Klebsiella quasipneumoniae is an emerging pathogen in human medicine. We report draft genome sequences of NDM-1- and KPC-2-producing K. quasipneumoniae strains from inpatients in Brazil. K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae harbored broad resistomes. These data could contribute to a better understanding of acquired resistance in K. quasipneumoniae.

ABSTRACT

Klebsiella quasipneumoniae is an emerging pathogen in human medicine. We report draft genome sequences of NDM-1- and KPC-2-producing K. quasipneumoniae strains from inpatients in Brazil. K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae harbored broad resistomes. These data could contribute to a better understanding of acquired resistance in K. quasipneumoniae.

ANNOUNCEMENT

Klebsiella pneumoniae strains of phylogenetic groups Kp1 to Kp7 have been classified as K. pneumoniae sensu stricto, K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae, K. variicola subsp. variicola, K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae, K. variicola subsp. tropicalensis, K. quasivariicola, and K. africanensis, respectively (1). Specifically, K. quasipneumoniae has been recognized as an opportunistic pathogen that can acquire clinically relevant antibiotic resistance genes (2–5). Here, we report draft genome sequences of two Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strains producing KPC-2 and NDM-1 carbapenemases, which confer resistance to all clinically relevant β-lactam antibiotics.

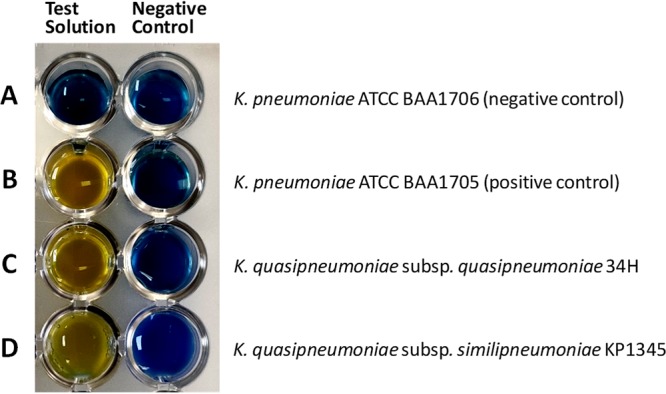

Carbapenem-resistant K. quasipneumoniae strains 34H and Kp1345 were isolated in 2014 from perfusion fluid (6) and in 2017 from a rectal swab for surveillance culture (7), respectively, from patients hospitalized in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Species identification was performed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (8), and antimicrobial susceptibility was determined with the Vitek 2 system (bioMérieux, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Carbapenemase production was detected by the Blue-Carba test (9) (Fig. 1) and modified Hodge test (10), whereas carbapenemase activity of NDM-1 and KPC-2 β-lactamases was confirmed by EDTA and dipicolinic acid inhibition assays, respectively (11–13). Additionally, blaNDM-1 and blaKPC-2 genes were identified by PCR amplification and direct DNA sequencing of PCR products (14).

FIG 1.

Representative results of the Blue-Carba test for carbapenemase-producing (B, C, and D) and non-carbapenemase-producing (A) bacteria, with test solutions (left) and negative-control solutions (right). (A) K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA1706 (carbapenemase-negative control); (B) K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA1705 (carbapenemase [KPC]-positive control); (C) K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae 34H (this study) (carbapenemase [KPC-2] positive); (D) K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae Kp1345 (this study) (carbapenemase [NDM-1] positive). The images were obtained after 2 h of incubation. Carbapenemase production was assessed by the Blue-Carba test method (9), which relies on the detection, in a bacterial extract, of hydrolysis of the carbapenem β-lactam ring through the acidification of a bromothymol blue test solution, used as a color indicator. The test solution consists of an aqueous solution of 0.04% bromothymol blue adjusted to pH 6.0, 0.1 mM ZnSO4, and 3 mg/ml imipenem, with a final pH of 7.0. A negative-control solution (0.04% bromothymol blue solution [pH 7.0]) is used to control for the influence of bacterial components or products on the pH of the solution. A loop (approximately 5 μl) of a pure bacterial culture recovered from Mueller-Hinton agar was directly suspended in 100 μl of both test and negative-control solutions in a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated for 2 h at 37°C with agitation (150 rpm). Carbapenemase activity was revealed when the test solution and negative-control wells were yellow and blue, respectively. The non-carbapenemase-producing strain (negative control) remained blue or green with both solutions.

For whole-genome sequencing (WGS) analyses, the strains were streaked to single colonies on MacConkey agar plates and then grown for 18 h at 37°C in 3 ml of lysogeny broth. Total genomic DNA was extracted using a PureLink quick gel extraction kit (Life Technologies, CA) and used for library preparation with a Nextera XT kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). In addition, the DNA was quantified with a double-stranded DNA high-sensitivity assay using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq PE instrument using a paired-end (150-bp) library. The short reads were handled using FastQC v.0.11.3 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) and Trimmomatic v.0.32 (15). De novo assembly was performed using SPAdes v.3.9 (16), and draft genome annotations were made using NCBI PGAP v.3.2 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/annotation_prok). Contamination levels were checked using CheckM v.1.0.3 with default settings (17). WGS data were analyzed using PlasmidFinder v.2.0 (18), ResFinder v.3.2 (19), and SpeciesFinder v.2.0 (20) tools (http://www.genomicepidemiology.org). Default parameters were used for all software.

Genome sequence analysis identified K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae (strain 34H) and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae (strain Kp1345), presenting a total of 16,501,776 and 10,695,728 paired-end reads assembled into 183 and 487 contigs, with 247.0× and 320.0× coverage, respectively. The N50 values obtained for strains 34H and Kp1345 were 84,397 and 122,604 bp, with GC contents of 57.6% and 56.8%, respectively. In brief, strain 34H presented a genome size calculated as 5,666,228 bp, with 5,134 protein-coding sequences, 82 tRNAs, 22 rRNAs, 12 noncoding RNAs, and 49 pseudogenes, whereas Kp1345 presented a genome size of 5,921,292 bp, with 5,134 protein-coding sequences, 82 tRNAs, 22 rRNAs, 12 noncoding RNAs, and 49 pseudogenes. CheckM results showed 99.99% and 99.938% completeness and 0.952% and 1.061% contamination for the 34H and KPC1345 genomes, respectively.

In summary, we present the draft genome sequences of two carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella quasipneumoniae strains displaying broad resistomes for β-lactams (i.e., blaKPC-2, blaOKP-A-6, blaOKP-B-2, blaNDM-1, and blaCTX-M-15) and other medically important antibiotics. These data could contribute to a better understanding of acquired resistance in K. quasipneumoniae.

Data availability.

The genome sequences of K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae strain 34H and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae strain Kp1345 have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers NZ_VDFT00000000 (SRA number SRR9950479) and NZ_VDFZ00000000 (SRA number SRR9942580), respectively. For a spreadsheet containing details of antibiotic resistance genes, plasmid incompatibility groups, and CheckM and Qubit results, see Table S1 at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11675805.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Explorations Brazil–New approaches to characterize the global burden of antimicrobial resistance (grant OPP1193112), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (grants AMR 443819/2018-1, 433128/2018-6, and 312249/2017-9), and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (grants 88887.358057/2019-00 and 1794306). N.L. is a research fellow of CNPq (grant 312249/2017-9), and L.C. is a former research fellow of CNPq (grant 443819/2018-1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Rodrigues C, Passet V, Rakotondrasoa A, Diallo TA, Criscuolo A, Brisse S. 2019. Description of Klebsiella africanensis sp. nov., Klebsiella variicola subsp. tropicalensis subsp. nov. and Klebsiella variicola subsp. variicola subsp. nov. Res Microbiol 170:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers AJ, Crook D, Vaughan A, Barry KE, Vegesana K, Stoesser N, Parikh HI, Sebra R, Kotay S, Walker AS, Sheppard AE. 2019. Klebsiella quasipneumoniae provides a window into carbapenemase gene transfer, plasmid rearrangements, and patient interactions with the hospital environment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 6:e02513-18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02513-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankar C, Karunasree S, Manesh A, Veeraraghavan B. 2019. First report of whole-genome sequence of colistin-resistant Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae producing KPC-9 in India. Microb Drug Resist 4:489–493. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolas MF, Ramos PIP, Marques de Carvalho F, Camargo DRA, de Fatima Morais Alves C, Loss de Morais G, Almeida LGP, Souza RC, Ciapina LP, Vicente ACP, Coimbra RS, Ribeiro de Vasconcelos AT. 2018. Comparative genomic analysis of a clinical isolate of Klebsiella quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae, a KPC-2 and OKP-B-6 beta-lactamases producer harboring two drug-resistance plasmids from southeast Brazil. Front Microbiol 9:220. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkac LM, White R, D’Souza R, Nguyen K, Obaro SK, Fouts DE. 2019. Emergence of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-5) in Klebsiella quasipneumoniae from neonates in a Nigerian hospital. mSphere 4:e00685-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00685-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salehi S, Tran K, Grayson WL. 2018. Advances in perfusion systems for solid organ preservation. Yale J Biol Med 91:301–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bansal S, Nguyen JP, Leligdowicz A, Zhang Y, Kain KC, Ricciuto DR, Coburn B. 2018. Rectal and naris swabs: practical and informative samples for analyzing the microbiota of critically ill patients. mSphere 3:e00219-18. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00219-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singhal N, Kumar M, Kanaujia PK, Virdi JS. 2015. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry: an emerging technology for microbial identification and diagnosis. Front Microbiol 6:791. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pires J, Novais A, Peixe L. 2013. Blue-Carba, an easy biochemical test for detection of diverse carbapenemase producers directly from bacterial cultures. J Clin Microbiol 51:4281–4283. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01634-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee K, Chong Y, Shin HB, Kim YA, Yong D, Yum JH. 2001. Modified Hodge and EDTA-disk synergy tests to screen metallo-β-lactamase-producing strains of Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter species. Clin Microbiol Infect 7:88–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2001.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimura S, Ishii Y, Yamaguchi K. 2005. Evaluation of dipicolinic acid for detection of IMP- or VIM-type metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 53:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoang CQ, Nguyen HD, Vu HQ, Nguyen AT, Pham BT, Tran TL, Nguyen HTH, Dao YM, Nguyen TSM, Nguyen DA, Tran HTT, Phan LT. 2019. Emergence of New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM) and Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) production by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Southern Vietnam and appropriate methods of detection: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int 2019:9757625. doi: 10.1155/2019/9757625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bou G, Vila J, Seral C, Castillo FJ. 2014. Detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in various scenarios and health settings. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 4:24–32. doi: 10.1016/S0213-005X(14)70171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poirel L, Walsh TR, Cuvillier V, Nordmann P. 2011. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemase genes. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 70:119–123. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Aarestrup FM, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV. 2012. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Lukjancenko O, Saputra D, Rasmussen S, Hasman H, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Aarestrup FM, Ussery DW, Lund O. 2014. Benchmarking of methods for genomic taxonomy. J Clin Microbiol 52:1529–1539. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02981-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences of K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae strain 34H and K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae strain Kp1345 have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers NZ_VDFT00000000 (SRA number SRR9950479) and NZ_VDFZ00000000 (SRA number SRR9942580), respectively. For a spreadsheet containing details of antibiotic resistance genes, plasmid incompatibility groups, and CheckM and Qubit results, see Table S1 at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11675805.