The intracellular lifestyle of bacteria is widely acknowledged to be an important mechanism in chronic and recurring infection. Among the Staphylococcus genus, only Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius have been clearly identified as intracellular in nonprofessional phagocytic cells (NPPCs), for which the mechanism is mainly fibronectin-binding dependent. Here, we used bioinformatics tools to search for possible new fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBP-like) in other Staphylococcus species.

KEYWORDS: fibronectin, fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs), integrin α5β1, nonprofessional phagocytic cells, Staphylococcus, host cell invasion

ABSTRACT

The intracellular lifestyle of bacteria is widely acknowledged to be an important mechanism in chronic and recurring infection. Among the Staphylococcus genus, only Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius have been clearly identified as intracellular in nonprofessional phagocytic cells (NPPCs), for which the mechanism is mainly fibronectin-binding dependent. Here, we used bioinformatics tools to search for possible new fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBP-like) in other Staphylococcus species. We found a protein in Staphylococcus delphini called Staphylococcus delphini surface protein Y (SdsY). This protein shares 68% identity with the Staphylococcus pseudintermedius surface protein D (SpsD), 36% identity with S. aureus FnBPA, and 39% identity with S. aureus FnBPB. The SdsY protein possesses the typical structure of FnBP-like proteins, including an N-terminal signal sequence, an A domain, a characteristic repeated pattern, and an LPXTG cell wall anchor motif. The level of adhesion to immobilized fibronectin was significantly higher in all S. delphini strains tested than in the fibronectin-binding-deficient S. aureus DU5883 strain. By using a model of human osteoblast infection, the level of internalization of all strains tested was significantly higher than with the invasive-incompetent S. aureus DU5883. These findings were confirmed by phenotype restoration after transformation of DU5883 by a plasmid expression vector encoding the SdsY repeats. Additionally, using fibronectin-depleted serum and murine osteoblast cell lines deficient for the β1 integrin, the involvement of fibronectin and β1 integrin was demonstrated in S. delphini internalization. The present study demonstrates that additional staphylococcal species are able to invade NPPCs and proposes a method to identify FnBP-like proteins.

INTRODUCTION

Bacteria belonging to the genus Staphylococcus, which comprises more than 50 species, are responsible for a variety of diseases from benign to serious infections originating from both community-acquired and nosocomial sources (1, 2). Staphylococcal infections are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality, and the latter reaches 30% in cases of bacteremia and up to 66% in cases of endocarditis (3, 4). Within the Staphylococcus genus, although Staphylococcus aureus is the most prevalent and virulent pathogen, Staphylococcus non-aureus (SNA) species, classically considered less virulent, opportunistic pathogens that are primarily responsible for chronic infections, have become major nosocomial pathogens (1, 5, 6). This could be explained by the increased numbers of immunocompromised patients, as well as by the use of inserted foreign bodies (7–9). However, the physiopathology of SNA-related infections remains far from being understood.

Conversely, various pathophysiological mechanisms have been identified to explain the development of chronic S. aureus infections, including the formation of biofilm, the secretion of specific virulence factors, and internalization into nonprofessional phagocytic cells (NPPCs) (7–13). The latter mechanism allows the bacteria to evade the host innate immune system and antibiotics and thus survive inside a wide variety of mammalian cells, which leads to chronic and recurring infection (14, 15). A plethora of studies have described this mechanism for S. aureus, showing that this bacterium can invade and persist within various NPPCs, such as epithelial cells (16), osteoblasts (17), and fibroblasts (18). The internalization of S. aureus into host cells is an active phenomenon from the cell side, controlled by the actin cytoskeleton, but is a passive phenomenon from the bacterial side. The integrin α5β1 binds to fibronectin of the extracellular matrix via the Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) motif (19). Bacterial surface fibronectin-binding proteins (FnBPs), belonging to microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs), bind the fibronectin to trigger bacterial internalization (20–23). Although alternative invasion mechanisms involving other MSCRAMMs have been proposed in the literature, the FnBP-fibronectin-α5β1 integrin pathway is predominant (24). FnBPs are characterized by a Sec-dependent secretory signal sequence at the N terminus, an N-terminal A domain comprising three separately folded subdomains (N1, N2, and N3), a variable fibronectin-binding repeat region, and a C-terminal sorting signal allowing covalent anchorage to the cell wall peptidoglycan by sortase. Two homologous FnBPs have been described for S. aureus, FnBPA and FnBPB, encoded, respectively, by the fnbA and fnbB loci, with very similar domain organizations and sequences (25). Although there is no doubt as to the capacity of S. aureus to be internalized in NPPCs and the pathophysiological consequences of this mechanism for infections, the question of whether SNA can also act as facultative intracellular pathogens in NPPCs is still debated. For instance, only a few MSCRAMMs involved in cellular internalization have been identified for the SNA species. We and others have described SpsD and SpsL, two FnBP-like proteins, as being sufficient for internalization of S. pseudintermedius in bone and epithelial cells via an interaction with fibronectin (22, 26). In addition to having strong homology with S. aureus FnBPs, SpsD and SpsL share the same characteristic motifs. For the other SNA species, the little data available are contradictory; for instance, while Hussain et al. suggested the involvement of the autolysin AtlL in the internalization process of Staphylococcus lugdunensis (27), other authors highlighted the incapacity of S. lugdunensis to be internalized in NPPCs using a panel of clinical and reference strains (26, 28).

To identify other species that can be internalized into NPPCs, we sought to identify FnBP-like proteins involved in the invasion process of NPPCs. Using in silico analysis and in vitro cellular models, we identified a new protein homologous to S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius fibronectin-binding proteins, named Staphylococcus delphini surface protein Y (SdsY), that is expressed by strains belonging to the species S. delphini that are responsible for human and animal infections (29–31).

RESULTS

In silico analysis and identification of new fnb gene homologs among clinical isolates.

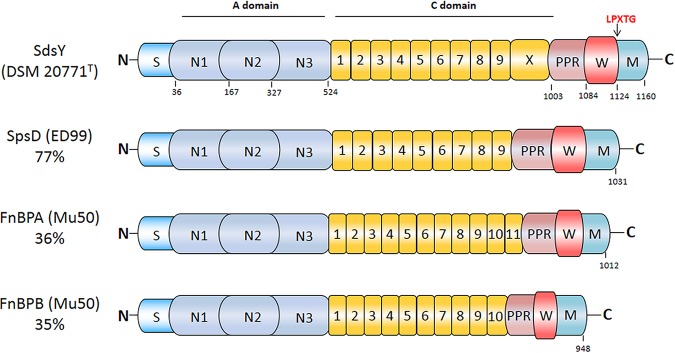

In silico searches allowed us to identify the hypothetical protein WP_019165356.1, which is encoded by the S. delphini strain 8086. This hypothetical protein, called Staphylococcus delphini surface protein Y (SdsY), presented 68% identity with the SpsD protein from the S. pseudintermedius strain ED99. Furthermore, this protein also had 36% identity with FnBPA and 39% identity with FnBPB from S. aureus Mu50. The SdsY protein encoded by S. delphini DSM 20771T has 77% identity with the SpsD protein of the S. pseudintermedius strain ED99 and possesses the typical motifs of MSCRAMM proteins, including an N-terminal signal sequence, an A domain, a characteristic repeat region, and an LPXTG cell wall anchor motif (Fig. 1). PCR amplification targeting sdsY revealed the presence of the gene in all S. delphini isolates (n = 7).

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of SdsY from S. delphini DSM 20771T. The SdsY protein includes a signal sequence (dark blue; S) at the N terminus, followed by an A domain spanning residues 37 to 524 (light blue; N1, N2, N3), a connecting domain in yellow containing nine tandem repeats with an immunoglobulin-like domain X (C; residues 525 to 1003), a proline-rich repeat spanning residues 1004 to 1084 (light red; PPR), and the wall (red; W) and membrane (cyan; M) spanning domains at the extreme C terminus residues 1085 to 1160 (22). The A domain of SdsY has 70% identity with SpsD, 38% identity with FnBPA, and 43% identity with FnBPB. The putative fibronectin binding region of SdsY has 73% identity with SpsD, 43% identity with FnBPA, and 41% identity with FnBPB.

Capacity to bind human fibronectin and to invade osteoblasts.

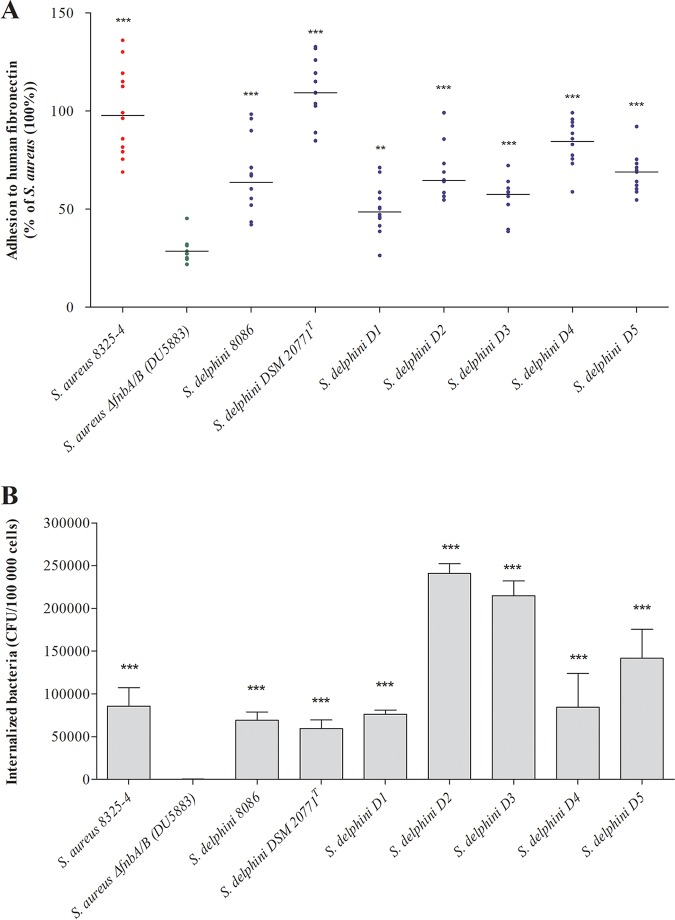

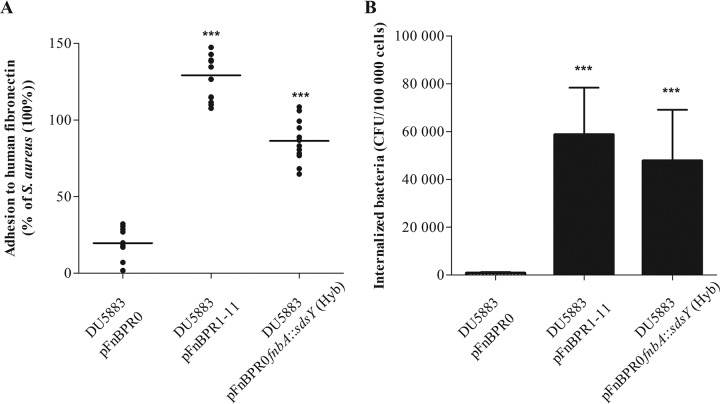

In vitro fibronectin binding assays found that all S. delphini strains tested adhered significantly more (mean ± standard deviation [SD], 50.0% ± 12.4% to 110.5% ± 15.3% relative to S. aureus 8325-4) than the negative-control S. aureus DU5883 lacking the fnbA and fnbB genes (29.4% ± 6.0%; all P < 0.001; Fig. 2A). In addition, the internalization levels in MG63 osteoblasts for all S. delphini strains were similar to or higher than that for S. aureus 8325-4 (Fig. 2B). In order to confirm the key role of the SdsY repeats for fibronectin binding and host cell invasion, we expressed in the invasive-incompetent S. aureus DU5883 strain a chimeric protein composed of the backbone (N-terminal A domain and C-terminal domain) of FnBPA of S. aureus with the predicted repeats of SdsY. The S. aureus DU5883 strain transformed with the pFnBPR0fnbA::sdsY (Hyb) showed significantly higher fibronectin adhesion and MG63 internalization than the S. aureus DU5883 strain carrying the empty plasmid pFnBPR0 (Fig. 3A and B). The expression of the SdsY repeats in the S. aureus DU5883 strain enabled recovery of adhesiveness and invasiveness similar to that of S. delphini DSM 20771.

FIG 2.

Determination of the capacity of S. delphini to adhere to human fibronectin in vitro and to be internalized in MG63 cells. (A) Quantification of the fibronectin adhesion capacity of seven S. delphini strains. All results are expressed as the proportion of the values obtained for the S. aureus 8325-4 strain. The horizontal bars indicate the mean derived from three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate, and statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using S. aureus ΔfnbA/B as a control with an α risk of 0.05 (**, P ≤ 0.001; ***, P ≤ 0.0001). (B) Quantification of S. delphini internalization in osteoblast MG63 cells. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation derived from three experiments performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as internalized bacterial CFU/100,000 cells. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using S. aureus ΔfnbA/B as a control with an α risk of 0.05 (***, P ≤ 0.0001).

FIG 3.

Determination of the capacity of the DU5883 strain complemented with pFnBR0, pFnBR1-11, or pFnBR0fnbA::sdsY (Hyb) to adhere to human fibronectin in vitro and to be internalized in MG63 cells. (A) Quantification of the fibronectin adhesion capacity of S. aureus DU5883 expressing pFnBR1-11 or pFnBR0fnbA::sdsY (Hyb). All results are expressed as the proportion of the values obtained for the S. aureus 8325-4 strain. The horizontal bars indicate the mean derived from three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using DU5883 pFnBPR0 as a control with an α risk of 0.05 (***, P ≤ 0.0001). (B) MG63 invasion by S. aureus DU5883 expressing pFnBR1-11 or pFnBR0fnbA::sdsY (Hyb). Internalized bacteria were measured as indicated above. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation from three independent experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using DU5883 pFnBPR0 as a control with an α risk of 0.05 (***, P ≤ 0.0001).

Characterization of the cellular pathways involved in the internalization process of S. delphini.

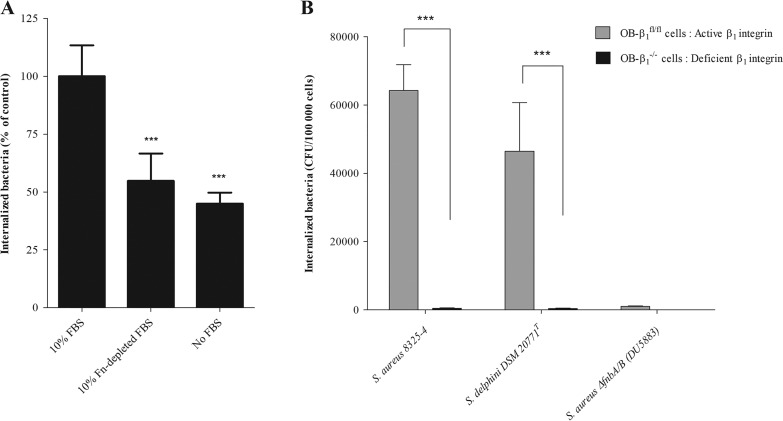

To determine whether internalization of S. delphini in osteoblasts involves the soluble plasma-derived fibronectin, fetal bovine serum (FBS) was fibronectin-depleted using gelatin-Sepharose affinity chromatography. The depletion of fibronectin (Fn-depleted FBS) reduced the invasion level by 45% (P < 0.0001) compared with control conditions (FBS; Fig. 4A). These observations suggest that S. delphini DSM 20771 uses soluble plasma-derived Fn in the internalization process. Of note, we observed that the capacity of S. delphini to invade osteoblasts was not totally abolished without plasma-derived Fn. We suggest that it could be explained by the presence of fibronectin produced by osteoblasts. To investigate the role of cellular integrin α5β1 in the internalization mechanism of S. delphini in osteoblasts, an in vitro model comparing two murine osteoblast cell lines, floxed OB-β1 (OB-β1fl/fl) and OB-β1−/−, was used. We investigated the internalization capacity of S. aureus 8325-4 (positive control), S. aureus DU5883 (negative control), and S. delphini DSM 20771T (reference strain). As expected, a complete loss of internalization of S. aureus 8325-4 was observed for OB-β1−/− cells compared to OB-β1fl/fl cells (P < 0.0001). A similar abolition was obtained for the S. delphini DSM 20771T strain comparing the two cell lines (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4B), which suggests that the S. delphini internalization process was widely mediated by the β1 integrin.

FIG 4.

Characterization of the cellular pathways involved in the internalization process of S. delphini. (A) Role of soluble fibronectin in invasion of S. delphini. The invasion assay was performed in the presence of 10% FBS (control condition), in the presence of 10% fibronectin-depleted FBS, and in the absence of FBS. Invasion is expressed as a percentage of that observed in the presence of 10% FBS. The horizontal bars indicate the mean derived from three independent experiments performed in quadruplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test using 10% FBS as a control with an α risk of 0.05 (***, P ≤ 0.0001). (B) Evaluation of the involvement of the β1 integrin in the S. delphini internalization process using murine osteoblast cell lines (OB-β1fl/fl and OB-β1−/−) with functional and nonfunctional β1 subunits, respectively. The internalization capacity of S. aureus 8325-4 (positive control), DU5883 S. aureus ΔfnbA/B (negative control), and the reference strain S. delphini DSM 20771T in OB-β1fl/fl and OB-β1−/− osteoblasts was measured 3 hours postinfection from three experiments performed in triplicate. The two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare the data obtained for the OB-β1fl/fl and OB-β1−/− osteoblasts with an α risk of 0.05 (***, P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The intracellular lifestyle provides various advantages for bacterial pathogens. After internalization in NPPCs, bacteria become inaccessible to humoral and complement-mediated attack; they avoid shear stress-induced clearance, and they evade antibiotic activities. Thus, bacterial intracellular location allows persistence of bacteria leading to chronic and recurrent infection (32). Host cell entry is the key step of the invasion process. Identifying the Staphylococcus species able to be internalized in host cells is crucial to better characterize a contributing pathophysiological mechanism related to SNA infections but also to provide new approaches for avoiding or preventing cellular invasion.

The in silico screening approach allowed us to identify a hypothetical protein, called SdsY, within the S. delphini genomes, which has identity with staphylococcal FnBPs/FnBP-like proteins. This protein has a high homology with the SpsD protein of S. pseudintermedius and shares all the characteristic domains of the FnBP type, including a secretory signal sequence at the N terminus, an N-terminal A domain, a C-terminal repeat region, and a C-terminal peptidoglycan-binding motif (LPXTG) (33). The analysis also found the presence of similar proteins already defined as FnBPs in the Staphylococcus argenteus and Staphylococcus schweitzeri genomes; both species have been recently described and belong to a complex closely related to S. aureus (34).

The screening approach used to detect FnBP-like protein may present some limitations. The results of this in silico screening method depend entirely on the sequences available in public databases, which are constantly evolving. For several staphylococcal species, only unassembled genomes are available, and as a consequence, the genes of interest can be truncated if they are located at the beginning or the end of a contig. Moreover, the identity and coverage thresholds, from which a protein may be considered FnBP-like, were set relatively high, and therefore it cannot be excluded that other proteins of interest have been missed using this approach. This is illustrated by the study reported by Ben Zakour et al., who used a different approach (BlastP with a minimum identity of 40% and minimum sequence coverage of 80%) to screen the distribution of virulence factors, including FnBP-like protein in eight staphylococcal species, including S. delphini, S. intermedius, S. epidermidis, and S. haemolyticus; they found no orthologous protein-coding sequences for FnBPA/B or for SpsD/L in the various genomes analyzed (35). However, high thresholds were chosen owing to the high functional redundancy of MSCRAMMs that have evolved to play multiple roles and so contain similar motifs that are, in fact, able to recognize variable and different proteins of the extracellular matrix (33, 36).

Using a panel of seven S. delphini isolates, we confirmed by PCR that all of the tested isolates were positive for the sdsY gene. Investigation of the capacity of S. delphini to be internalized into NPPCs found homogeneous behavior among the seven tested strains. In line with in silico findings, the in vitro results revealed that all strains were able to be internalized in the intracellular compartment of human osteoblasts. Currently, among staphylococci, only S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius are reported as intracellular pathogens; in both, fibronectin is involved in the internalization process by forming a bridge between the α5β1 integrin on the cellular side and FnBP-like protein (FnBPA/B and SpsD/L) on the bacteria (22, 26). Additionally, using fibronectin-depleted serum and murine osteoblast cell lines deficient for β1 integrin, the involvement of fibronectin and β1 integrin was demonstrated in S. delphini internalization. Especially described in animal infections such as Equidae and Mustilidae, a recent study demonstrates the involvement of S. delphini in human infections (29–31). Considering the complexity of identifying Staphylococcus intermedius group (SIG) species in a routine diagnostic laboratory, the prevalence of S. delphini-related infections is likely to be underestimated (37). Like S. aureus and S. pseudintermedius, S. delphini has the ability to invade NPPCs using an FnBP-fibronectin-α5β1 integrin pathway. The results of the present study suggest that these 3 species that belong to the coagulase-positive staphylococcus (CoPS) group share a pathophysiological mechanism that can explain the genesis of infections. The results also prompt further studies of the various species belonging to the Staphylococcus genus to accurately investigate the ability of these species to be internalized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In silico analysis of fibronectin-binding protein homologs.

The search for FnBP homologs was performed using the BlastX search algorithm (translated nucleotide protein query against protein database; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and NCBI’s nonredundant (nr) protein database (38). We used as query sequences the fnb genes currently characterized in the literature, fnbA and fnbB of S. aureus Mu50 and spsD and spsL of S. pseudintermedius ED99 (39, 40). The search was restricted to the Staphylococcus group (taxid: 90964); the S. aureus (taxid: 1280) and S. pseudintermedius (taxid: 283734) species were excluded from the search. All results with a minimum identity of ≥ 50% and a minimum sequence coverage of ≥ 80% were considered positive. The identification of a hypothetical SdsY in the genome of S. delphini strain 8086 (GenBank accession number NZ_CAIA01000117.1) led us to sequence the genome of the reference strain, S. delphini DSM20771T (ATCC 49171), and deposit it in the GenBank database under the BioProject number PRJNA389509. The predicted FnBP-like proteins were further characterized by searching for functional domains using EMBL-EBI InterPro Scan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro) (41).

Bacterial strains and culture media.

Seven S. delphini isolates were included in the study: five clinical strains isolated from camelids (42), the strain S. delphini 8086 isolated from Equidae (35), and the reference strain S. delphini DSM 20771T, isolated from a dolphin (43) (Table 1). As described by Gharsa et al., the identification was carried out using PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the pta gene with the MboI enzyme (supplemental material S1) (31, 44). The strain S. aureus 8325-4, a strain well characterized for its ability to bind fibronectin and to invade osteoblasts, was used as a positive control in each experiment. Its isogenic mutant, DU5883 ΔfnbA/B (inactivated for the fnbAB genes and therefore unable to adhere to or invade osteoblasts), was used as a negative control (Table 1). Prior to the assays, strains were incubated overnight in brain heart infusion medium (BHI; bioMérieux, Marcyl’Etoile, France) aerobically at 36°C for 18 hours.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in the present study

| Species | Strain code | Origin | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | 8325-4 | Human | 54 |

| S. aureus ΔfnbA/B | DU 5883 | Human | 55 |

| S. aureus ΔfnbA/B | DU 5883 (pFnBPR1-11) | Human | 51 |

| S. aureus ΔfnbA/B | DU 5883 (pFnBPR0) | Human | 51 |

| S. aureus ΔfnbA/B | DU 5883 (pFnBPR0fnbA::sdsY [Hyb]) | Human | This study |

| S. delphini | 8086 | Horse | 35 |

| S. delphini | DSM 20771T | Dolphin | 43 |

| S. delphini | HT 20030674 (D1) | Camel | 42 |

| S. delphini | HT 20030676 (D2) | Camel | 42 |

| S. delphini | HT 20030677 (D3) | Camel | 42 |

| S. delphini | HT 20030679 (D4) | Camel | 42 |

| S. delphini | HT 20030680 (D5) | Camel | 42 |

Illumina sequencing and de novo assembly.

S. delphini DSM 20771T genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAcube extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The Nextera XT DNA preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to generate sequencing libraries from 1 ng of DNA. Whole-genome sequencing was done using an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer to generate 150-bp paired-end reads. The raw paired-end reads were cleaned of potential contamination by the adapters during the Nextera XT protocol using Trimmomatic v0.36 (45). After being quality filtered, the reads were assembled with SPAdes v3.9.0 using the “careful” option and with the SPAdes error correction (BayesHammer module) turned on (46).

Detection of target genes in S. delphini isolates.

The consensus sequence for the sdsY gene was obtained using Seaview software v4.5.4 after aligning the sequences obtained from the two public whole-genome sequences (WGS) of S. delphini strains (strains 8086 [GenBank accession number NZ_CAIA01000117.1] and DSM 20771T [BioProject number PRJNA389509]) (47). Specific primers selected from the consensus sequence of the gene of interest (sdsY) were designed using Primer 3 software and are listed in Table S1 (48). The reaction mixture and the PCR program used for amplification are available in Tables S2 and S3.

Expression of the SdsY repeats into S. aureus lacking fnbAB genes.

The plasmids pFnBR0 (which expresses an FnBPA variant containing no fibronectin-binding repeats) and pFnBR1-11 (which expresses the full length of FnBPA) were kindly provided by Ruth Massey (49). We inserted the putative binding domain of SdsY (residues 525 to 1003) into the plasmid pFnBPR0 using a prolonged overlap extension-PCR (POE-PCR) strategy (50, 51). Briefly, the insert corresponding to the repeats of SdsY was amplified from the genomic DNA of the S. delphini strain DSM20771, using Q5 HotSart polymerase (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) with the primers Rfor (5′-GCGAACGGAAATGAGAAAAATACTTATTCTCCTGTAATGACTTTCCA-3′) and Rrev (5′-GGCGTTGGTGGCACGATTGGTTCG/ATTTTCTTTAGGATCTTTTGGCT-3′). The pFnBR1-11 plasmid was opened with inverse PCR using primers that were designed to delete the repeats of FnBPA (5′-TGGAAAGTCATTACAGGAGAATAAGTATTTTTCTCATTTCCGTTCGC-3′) (Nrev) and (5′-AGCCAAAAGATCCTAAAGAAAATGAACCAATCGTGCCACCAACGCC-3′) (Cfor) to obtain the open plasmid pFnBPR0. After being cleaned up using the MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen), the products of each PCR were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio at a concentration of 2 ng/μl for the insert (repeats of SdsY), and the POE-PCR was run as previously described (50). Then, Escherichia coli DH5α was transformed with 5 μl of the POE-PCR product, and positive clones containing pFnBR0fnbA::sdsY (Hyb) were selected on LB plus ampicillin (100 μg/ml). After plasmid purification from E. coli using a miniprep kit (Qiagen), the S. aureus RN4220 strain was transformed by electroporation, and positive clones were selected on Trypticase soy agar (TSA; bioMérieux) plus chloramphenicol (10 μg/ml) as previously described (51). Plasmids were recovered using a combination of lysostaphin and the Qiagen miniprep kit and retransformed into the invasive-incompetent S. aureus DU5883 strain.

Microplate adhesion to fibronectin assay.

The fibronectin adhesion assay was performed in vitro in 96-well flat-bottom plates as previously described (52). Briefly, the wells were coated with 200 μl of human fibronectin (Dutscher SAS, Brumath, France) at 50 μg/ml (18 h, 4°C). They were then washed three times (20 min, 37°C) with PBS supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Meanwhile, after an overnight broth culture in BHI at 36°C, bacterial suspensions were adjusted to an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 1 ± 0.05, corresponding to approximately 1 × 109 cells/ml. Then, 1 ml of each suspension was centrifuged (12,000 × g, 2 min), and pellets were washed and suspended in PBS. Next, 100 μl of each bacterial suspension was incubated in the fibronectin-coated plate for 30 min at 37°C with mild shaking. Wells were then washed 3 times with PBS to remove nonadherent bacteria. Adherent bacteria were fixed with glutaraldehyde (2.5% vol/vol in 0.1 M PBS for 2 h at 4°C) and stained with crystal violet (0.1% mass/vol) for 30 min at room temperature. After 3 PBS washes, the total remaining stain impregnating the adherent bacteria was solubilized using 100 μl Triton X-100 solution (0.2% vol/vol H2O; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for 30 min. Quantification of adherent bacteria to fibronectin was assessed by measuring the OD620 for each well using a spectrophotometer (Auto Reader model 680; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The results were expressed as the mean of OD620 in 3 experiments performed in quadruplicate. The values were normalized to the reference strain, S. aureus 8325-4.

Cell culture.

All cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco (Paisley, UK). Human MG63 osteoblastic cells (LGC Standards, Teddington, UK) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 2 mM l-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES, supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin (“growth medium with antibiotics”). Two murine osteoblastic cell lines were used for the quantification of the internalization process: the OB-β1fl/fl cell line, expressing the functional integrin β1 subunit, and the OB-β1−/− cell line, deficient in the expression of the β1 integrin subunit after the conditional deletion of the itgb1 gene. As previously described, both cell lines were derived from calvaria of transgenic mice bearing itgb1-floxed alleles. OB-β1fl/fl cells were then immortalized via retroviral infection with the SV40 large T-antigen; OB-β1−/− cells were obtained from the parental OB-β1fl/fl cell line after expressing Cre recombinase (53). All cells were maintained at 1 passage per week.

Determination of the invasion capacity of S. delphini strains.

Osteoblasts were seeded at 80,000 cells per well into 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon, Le Pont-de-Claix, France) in 1 ml of growth medium with antibiotics. One day later, cells were washed twice with 1 ml of DMEM before the addition of bacteria. Bacterial suspensions in growth medium without antibiotics or in growth medium fibronectin-depleted (Fn-depleted FBS) were added to the cell culture wells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 as previously described (17) (see supplemental material S1). After 2 h of coculture of bacteria and osteoblasts in a 37°C/5% CO2 incubator, the wells were washed twice with 1 ml of DMEM. They were then incubated for 1 h in medium containing 200 μg/ml gentamicin to specifically kill the extracellular bacteria. To evaluate the internalization rate, osteoblasts were then lysed by osmotic shock using water, and dilutions of cell lysates were plated using the easySpiral instrument (Interscience, Saint Nom, France) in duplicate on Trypticase soy agar (TSA; bioMérieux) plates before being incubated at 36°C to quantify the number of colonies corresponding to intracellular bacteria.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons were made using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test for multiple comparison and Student’s t test for two-group comparison; P values below 5% were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM) and Allocations de Recherche du Ministère de la Recherche. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We thank the Reference National Center of Staphylococci for the strain collection. We thank Ruth Massey (Bristol, UK), who kindly provided the plasmids pFnBR0 and pFnBR1-11. We thank Philip Robinson for language editing and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. 2014. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev 27:870–926. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00109-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster AP. 2012. Staphylococcal skin disease in livestock. Vet Dermatol 23:342–351.e63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2012.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG Jr. 2015. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Hal SJ, Jensen SO, Vaska VL, Espedido BA, Paterson DL, Gosbell IB. 2012. Predictors of mortality in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev 25:362–386. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05022-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beca N, Bessa LJ, Mendes A, Santos J, Leite-Martins L, Matos AJ, da Costa PM. 2015. Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus: prevalence and antimicrobial resistance. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 51:365–371. doi: 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-6255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman JC, Bauman SE, Daniel CR III. 2013. Coagulase positive staphylococcal infection: a major cause of eczema exacerbations. J Miss State Med Assoc 54:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hira V, Kornelisse RF, Sluijter M, Kamerbeek A, Goessens WH, de Groot R, Hermans PW. 2013. Colonization dynamics of antibiotic-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in neonates. J Clin Microbiol 51:595–597. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02935-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A, Kallen A, Limbago B, Fridkin S, National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Team and Participating NHSN Facilities. 2013. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 34:1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Eiff C, Peters G, Heilmann C. 2002. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infect Dis 2:677–685. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otto M. 2008. Staphylococcal biofilms. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 322:207–228. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bui LM, Conlon BP, Kidd SP. 2017. Antibiotic tolerance and the alternative lifestyles of Staphylococcus aureus. Essays Biochem 61:71–79. doi: 10.1042/EBC20160061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seilie ES, Wardenburg JB. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus pore-forming toxins: the interface of pathogen and host complexity. Semin Cell Dev Biol 72:101–116. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill PB, Imai A. 2016. The immunopathogenesis of staphylococcal skin infections: a review. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 49:8–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rollin G, Tan X, Tros F, Dupuis M, Nassif X, Charbit A, Coureuil M. 2017. Intracellular survival of Staphylococcus aureus in endothelial cells: a matter of growth or persistence. Front Microbiol 8:1354. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamza T, Dietz M, Pham D, Clovis N, Danley S, Li B. 2013. Intra-cellular Staphylococcus aureus alone causes infection in vivo. Eur Cell Mater 25:341–350. 10.22203/ecm.v025a24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JH, Zhang K, Wang N, Qiu XM, Wang YB, He P. 2013. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway in beta1 integrin-mediated internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by alveolar epithelial cells. J Microbiol 51:644–650. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trouillet S, Rasigade JP, Lhoste Y, Ferry T, Vandenesch F, Etienne J, Laurent F. 2011. A novel flow cytometry-based assay for the quantification of Staphylococcus aureus adhesion to and invasion of eukaryotic cells. J Microbiol Methods 86:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haggar A, Hussain M, Lonnies H, Herrmann M, Norrby-Teglund A, Flock JI. 2003. Extracellular adherence protein from Staphylococcus aureus enhances internalization into eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun 71:2310–2317. doi: 10.1128/iai.71.5.2310-2317.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huveneers S, Truong H, Fassler R, Sonnenberg A, Danen EH. 2008. Binding of soluble fibronectin to integrin alpha5 beta1: link to focal adhesion redistribution and contractile shape. J Cell Sci 121:2452–2462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.033001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmed S, Meghji S, Williams RJ, Henderson B, Brock JH, Nair SP. 2001. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin binding proteins are essential for internalization by osteoblasts but do not account for differences in intracellular levels of bacteria. Infect Immun 69:2872–2877. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2872-2877.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha B, Francois P, Que YA, Hussain M, Heilmann C, Moreillon P, Lew D, Krause KH, Peters G, Herrmann M. 2000. Heterologously expressed Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding proteins are sufficient for invasion of host cells. Infect Immun 68:6871–6878. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.6871-6878.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pietrocola G, Gianotti V, Richards A, Nobile G, Geoghegan JA, Rindi S, Monk IR, Bordt AS, Foster TJ, Fitzgerald JR, Speziale P. 2015. Fibronectin binding proteins SpsD and SpsL both support invasion of canine epithelial cells by Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Infect Immun 83:4093–4102. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00542-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster TJ, Hook M. 1998. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol 6:484–488. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josse J, Laurent F, Diot A. 2017. Staphylococcal adhesion and host cell invasion: fibronectin-binding and other mechanisms. Front Microbiol 8:2433. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jonsson K, Signas C, Muller HP, Lindberg M. 1991. Two different genes encode fibronectin binding proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. The complete nucleotide sequence and characterization of the second gene. Eur J Biochem 202:1041–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maali Y, Martins-Simoes P, Valour F, Bouvard D, Rasigade JP, Bes M, Haenni M, Ferry T, Laurent F, Trouillet-Assant S. 2016. Pathophysiological mechanisms of Staphylococcus non-aureus bone and joint infection: interspecies homogeneity and specific behavior of S. pseudintermedius. Front Microbiol 7:1063. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussain M, Steinbacher T, Peters G, Heilmann C, Becker K. 2015. The adhesive properties of the Staphylococcus lugdunensis multifunctional autolysin AtlL and its role in biofilm formation and internalization. Int J Med Microbiol 305:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campoccia D, Testoni F, Ravaioli S, Cangini I, Maso A, Speziale P, Montanaro L, Visai L, Arciola CR. 2016. Orthopedic implant infections: incompetence of Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus lugdunensis and Enterococcus faecalis to invade osteoblasts. J Biomed Mater Res A 104:788–801. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magleby R, Bemis DA, Kim D, Carroll KC, Castanheira M, Kania SA, Jenkins SG, Westblade LF. 2019. First reported human isolation of Staphylococcus delphini. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 94:274–276. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guardabassi L, Schmidt KR, Petersen TS, Espinosa-Gongora C, Moodley A, Agersø Y, Olsen JE. 2012. Mustelidae are natural hosts of Staphylococcus delphini group A. Vet Microbiol 159:351–353. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gharsa H, Slama KB, Gomez-Sanz E, Gomez P, Klibi N, Zarazaga M, Boudabous A, Torres C. 2015. Characterisation of nasal Staphylococcus delphini and Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from healthy donkeys in Tunisia. Equine Vet J 47:463–466. doi: 10.1111/evj.12305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ray K, Marteyn B, Sansonetti PJ, Tang CM. 2009. Life on the inside: the intracellular lifestyle of cytosolic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster TJ, Geoghegan JA, Ganesh VK, Hook M. 2014. Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tong SY, Schaumburg F, Ellington MJ, Corander J, Pichon B, Leendertz F, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Holt DC, Peters G, Giffard PM. 2015. Novel staphylococcal species that form part of a Staphylococcus aureus-related complex: the non-pigmented Staphylococcus argenteus sp. nov. and the non-human primate-associated Staphylococcus schweitzeri sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 65:15–22. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.062752-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben Zakour NL, Beatson SA, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR. 2012. Comparative genomics of the Staphylococcus intermedius group of animal pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:44. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keane FM, Loughman A, Valtulina V, Brennan M, Speziale P, Foster TJ. 2007. Fibrinogen and elastin bind to the same region within the A domain of fibronectin binding protein A, an MSCRAMM of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 63:711–723. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee J, Murray A, Bendall R, Gaze W, Zhang L, Vos M. 2015. Improved detection of Staphylococcus intermedius group in a routine diagnostic laboratory. J Clin Microbiol 53:961–963. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02474-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben Zakour NL, Bannoehr J, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR. 2011. Complete genome sequence of the canine pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Bacteriol 193:2363–2364. doi: 10.1128/JB.00137-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuroda M, Ohta T, Uchiyama I, Baba T, Yuzawa H, Kobayashi I, Cui L, Oguchi A, Aoki K, Nagai Y, Lian J, Ito T, Kanamori M, Matsumaru H, Maruyama A, Murakami H, Hosoyama A, Mizutani-Ui Y, Takahashi NK, Sawano T, Inoue R, Kaito C, Sekimizu K, Hirakawa H, Kuhara S, Goto S, Yabuzaki J, Kanehisa M, Yamashita A, Oshima K, Furuya K, Yoshino C, Shiba T, Hattori M, Ogasawara N, Hayashi H, Hiramatsu K. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225–1240. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bannoehr J, Ben Zakour NL, Reglinski M, Inglis NF, Prabhakaran S, Fossum E, Smith DG, Wilson GJ, Cartwright RA, Haas J, Hook M, van den Broek AH, Thoday KL, Fitzgerald JR. 2011. Genomic and surface proteomic analysis of the canine pathogen Staphylococcus pseudintermedius reveals proteins that mediate adherence to the extracellular matrix. Infect Immun 79:3074–3086. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00137-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bannoehr J, Ben Zakour NL, Waller AS, Guardabassi L, Thoday KL, van den Broek AH, Fitzgerald JR. 2007. Population genetic structure of the Staphylococcus intermedius group: insights into agr diversification and the emergence of methicillin-resistant strains. J Bacteriol 189:8685–8692. doi: 10.1128/JB.01150-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Varaldo PE, Kilpper-Bälz R, Biavasco F, Satta G, Schleifer KH. 1988. Staphylococcus delphini sp. nov., a coagulase-positive species isolated from dolphins. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 38:436–439. doi: 10.1099/00207713-38-4-436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannoehr J, Franco A, Iurescia M, Battisti A, Fitzgerald JR. 2009. Molecular diagnostic identification of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J Clin Microbiol 47:469–471. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01915-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. 2010. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol 27:221–224. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Untergasser A, Cutcutache I, Koressaar T, Ye J, Faircloth BC, Remm M, Rozen SG. 2012. Primer3: new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edwards AM, Potter U, Meenan NA, Potts JR, Massey RC. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus keratinocyte invasion is dependent upon multiple high-affinity fibronectin-binding repeats within FnBPA. PLoS One 6:e18899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.You C, Zhang XZ, Zhang YH. 2012. Simple cloning via direct transformation of PCR product (DNA multimer) to Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1593–1595. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07105-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards AM, Potts JR, Josefsson E, Massey RC. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus host cell invasion and virulence in sepsis is facilitated by the multiple repeats within FnBPA. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000964. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rasigade JP, Moulay A, Lhoste Y, Tristan A, Bes M, Vandenesch F, Etienne J, Lina G, Laurent F, Dumitrescu O. 2011. Impact of sub-inhibitory antibiotics on fibronectin-mediated host cell adhesion and invasion by Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol 11:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brunner M, Millon-Frémillon A, Chevalier G, Nakchbandi IA, Mosher D, Block MR, Albigès-Rizo C, Bouvard D. 2011. Osteoblast mineralization requires beta1 integrin/ICAP-1-dependent fibronectin deposition. J Cell Biol 194:307–322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novick R. 1967. Properties of a cryptic high-frequency transducing phage in Staphylococcus aureus. Virology 33:155–166. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greene C, McDevitt D, Francois P, Vaudaux PE, Lew DP, Foster TJ. 1995. Adhesion properties of mutants of Staphylococcus aureus defective in fibronectin-binding proteins and studies on the expression of fnb genes. Mol Microbiol 17:1143–1152. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17061143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.