Abstract

Introduction

Prevalence estimates of electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use may underestimate actual use in youth. Confusion resulting from the fact that a multitude of devices (eg, vape pens, JUULs) fall under the umbrella term “e-cigarettes,” the use of different names to refer to e-cigarettes (eg, vapes, electronic vaping devices), and the use of different terminology to refer to e-cigarette use (eg, “vaping,” “JUULing”), may lead some young e-cigarette users to incorrectly indicate nonuse. Therefore, we compared rates of endorsing lifetime e-cigarette use when adolescents were asked about lifetime e-cigarette use in two different ways.

Methods

In May to June 2018, a total of 1960 students from two high schools in Connecticut completed a computerized, school-based survey. Participants first reported on lifetime “e-cigarette” use and, subsequently, on lifetime use of five different e-cigarette devices: disposables, cig-a-likes, or E-hookahs; vape pens or Egos; JUULs; pod systems other than JUULs such as PHIX or Suorin; and advanced personal vaporizers or mods.

Results

In total, 35.8% of students endorsed lifetime “e-cigarette” use, whereas 51.3% endorsed lifetime use of at least one e-cigarette device. The kappa statistic indicated only 66.6% agreement between the methods of assessing e-cigarette use. Overall, 31.5% of adolescents who endorsed lifetime device use did not endorse lifetime “e-cigarette” use, although rates of discordant responding varied across subgroups of interest (eg, sex, race).

Conclusions

Assessing adolescents’ use of specific e-cigarette devices likely yields more accurate results than assessing the use of “e-cigarettes.” If these findings are replicated in a nationally representative sample, regulatory efforts requiring all e-cigarette devices to be clearly labeled as “e-cigarettes” may help to reduce confusion.

Implications

Different prevalence estimates of lifetime e-cigarette use were obtained depending on the way that prevalence was assessed. Specifically, fewer adolescents (35.8%) endorsed lifetime e-cigarette use when they were asked “Have you ever tried an e-cigarette, even one or two puffs?” than when they were queried about lifetime use of five different e-cigarette devices (51.3%). Among those who endorsed lifetime use of at least one specific e-cigarette device, 31.5% did not endorse lifetime “e-cigarette” use. These findings suggest that when assessing adolescents’ lifetime e-cigarette use, using of terms referring to specific devices likely produces more accurate prevalence estimates than using the term “e-cigarettes.”

Introduction

In 2016, the Surgeon General highlighted youth electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use as a major public health concern.1 Since 2014, e-cigarettes have been the most commonly used tobacco product among adolescents,2 with recent estimates suggesting that 34% of high school seniors and 21% of eighth grade students have tried an e-cigarette.3 However, there is reason to believe that current estimates of youth e-cigarette use may underestimate the actual prevalence of use. For example, many studies assess e-cigarette use using variants of the following question: “Have you ever used an e-cigarette, even once or twice?”.4 Typically, only participants who indicate lifetime use are asked subsequent questions related to e-cigarette use, meaning that all additional information that is collected about e-cigarette use hinges on an affirmative answer to the initial question. However, it is possible that there is confusion about what exactly constitutes e-cigarette use and that some participants who actually use e-cigarettes incorrectly indicate that they do not (ie, are misclassified). This confusion may arise from the fact that the term “e-cigarette” is used to describe a wide range of devices including cig-a-likes; mid-size e-cigarettes such as vape pens, advanced personal vaporizers (APVs), and mods; and pod-based systems such as the JUUL. Potential confusion may also be linked to the fact that e-cigarettes are known by many different names (eg, e-cigs, vapes, electronic nicotine delivery systems, electronic vaping devices) and that terms that make no direct reference to e-cigarette use, such as “vaping,” or, in the case of JUUL use, “JUULing,” often are used to refer to e-cigarette use.5 In sum, the wide variety of e-cigarette devices and the various terms that are used to describe them and their use may lead to misperceptions in endorsing use.

Thus, in this study, we compared rates of endorsing lifetime e-cigarette use when adolescents were asked “Have you ever tried an e-cigarette, even one or two puffs?” (accompanied by a picture of multiple exemplar e-cigarette devices) versus when they were asked to indicate lifetime use of five different e-cigarette devices. We anticipated that the rate of lifetime e-cigarette use calculated based on the endorsement of using at least one of the five e-cigarette devices (referred to as lifetime vaping) would exceed the rate of lifetime e-cigarette use based on the broader question assessing “e-cigarette” use (referred to as lifetime e-cigarette use). If our hypothesis were supported, this would indicate that adolescents may be confused about what constitutes an e-cigarette and that querying about the use of specific e-cigarette devices may be needed to yield a more accurate estimate of e-cigarette use prevalence among youth. We also examined whether rates of misclassification differed by sex, race, lifetime use of traditional tobacco products, and lifetime use of each e-cigarette device.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

In May to June 2018, a total of1960 students from two high schools in Connecticut completed an anonymous, 25-minute, computerized, school-based survey (51.5% female, 49% non-Hispanic white, mean age of 16.12 [SD = 1.28] years). All participants used handheld tablets provided by the study staff to complete the survey, which was hosted on Qualtrics. Once a participant answered a question, he or she was unable to use the “back” function to view or change responses to previously answered questions.

Measures

Participants first answered the following question: “Have you ever tried an e-cigarette, even one or two puffs?” (no or yes). Irrespective of the answer provided to the first question, on the next page, all participants were then asked about lifetime use of each the following devices: (1) disposables, cig-a-likes, or E-hookah; (2) vape pens or Egos; (3) JUULs; (4) any pod system other than a JUUL, such as a PHIX or Suorin; and (5) mods or APVs. Adolescents were asked about lifetime use of each device separately (no/yes) and were provided with example pictures of each device and a brief description based on previous research suggesting that assessing tobacco product use using forced choice response options (no/yes) accompanied by product pictures likely yields more reliable use estimates compared to alternative approaches (eg, a “check all that apply” response format6 and/or one that does not include product pictures7). Adolescents also reported on lifetime use of traditional tobacco products including cigarettes, cigarillos, cigars, hookah, blunts, and smokeless tobacco (no/yes for each product).

Data Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were run for lifetime e-cigarette use, lifetime use of each device, and lifetime vaping. A binary logistic regression was then run to examine potential predictors of misclassification as a never “e-cigarette” user (ie, endorsing lifetime vaping but not lifetime e-cigarette use). Independent variables included sex (female/male), race (non-Hispanic white vs. other), age, lifetime use of any traditional tobacco product (no/yes), and lifetime use of each of the five e-cigarette devices (no/yes). We subsequently examined rates of concordant and discordant responding and calculated kappa coefficients (as applicable) to evaluate the level of agreement between lifetime e-cigarette use and lifetime vaping within the total sample and for the subgroups of interest.

Results

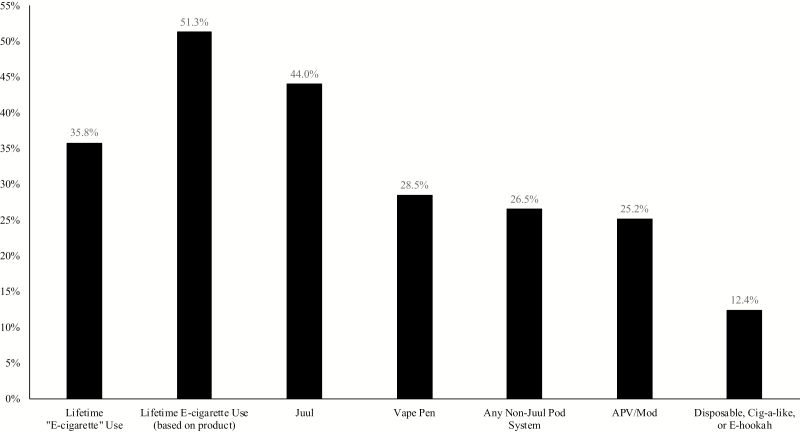

Missing data were minimal (0 for all product use variables, 1 for sex, 1 for age, and 3 for race). In total, 35.8% of students endorsed lifetime e-cigarette use whereas 51.3% endorsed lifetime vaping. When rates of individual device use were assessed, JUULs were used most commonly (44.0%), followed by vape pens or Egos (28.5%), pod systems other than JUULs (26.5%), mods or APVs (25.2%), and disposables, cig-a-likes, or E-hookahs (12.4%; Figure 1). Lifetime use of any traditional tobacco product(s) was 39.1%.

Figure 1.

Rates of lifetime electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use, use of any e-cigarette device, and use of specific e-cigarette devices. APV = advanced personal vaporizers.

The binary logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(9) = 189.75, p < .001 (see Table 1). The model explained 24.1% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in misclassification as being a never “e-cigarette” user and correctly classified 72.6% of cases. Misclassification was associated with being female (OR = 1.63, p = .001), reporting a racial background other than non-Hispanic white (OR = 2.73, p < .001), and never using traditional tobacco products (OR = 1.50, p = .028), disposables, cig-a-likes, or E-hookahs (OR = 3.55, p < .001); vape pens or Egos (OR = 1.76, p = .001); JUULs (OR = 2.01, p = .001); and other pod-based systems (OR = 1.93, p < .001). Age (OR = 1.07, p = .289) and Mod or APV use (OR = 1.01, p = .944) were not significantly associated with misclassification.

Table 1.

Predictors of Underreporting Lifetime E-Cigarette Use Among Students Endorsing Lifetime Electronic Cigarette (E-Cigarette) Device Use

| Independent variables | Unstandardized coefficients | Adjusted odds ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ||

| Female | 0.49 | 0.15 | 1.63** |

| Nonwhite | 1.00 | 0.16 | 2.73*** |

| Age | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.07 |

| Lifetime product use | |||

| No traditional tobacco products | 0.40 | 0.18 | 1.50* |

| No disposable, cig-a-like, or E-hookah | 1.27 | 0.23 | 3.55*** |

| No vape pen or Ego | 0.56 | 0.17 | 1.76** |

| No JUUL | 0.70 | 0.22 | 2.01** |

| No other pod-based system | 0.66 | 0.17 | 1.93*** |

| No mod or APV | 0.01 | 0.17 | 1.01 |

APV = advanced personal vaporizers, SE = standard error. Nagelkerke R2 = 0.24.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Within the total sample, lifetime vaping (51.3%) was endorsed by significantly more adolescents than lifetime e-cigarette use (35.8%), χ2(1) = 959.58. In total, 83.2% of all students provided concordant responses for the two definitions of e-cigarette use (ie, endorsed both lifetime e-cigarette use and lifetime vaping or did not endorse both lifetime e-cigarette use and vaping), with an overall kappa statistic of 0.67 (see Table 2). Importantly, among students who endorsed lifetime vaping, 68.5% provided concordant responses whereas 31.5% provided discordant responses (ie, did not endorse lifetime e-cigarette use). Rates of discordant responding also varied within the other subgroups of interest. A greater percentage of discordant responses were observed among females (36.8%) compared to males (25.6%) and among non-white students (41.5%) compared to non-Hispanic white students (22.7%). Among individuals who reported lifetime tobacco product use and/or specific e-cigarette device use, rates of discordant responses ranged from 14.4% (disposable, cig-a-like, or E-hookah) to 28.4% (JUUL). In general, higher rates of discordant responses were observed among never product users, ranging from 37.0% (never disposable, cig-a-like, or E-hookah) to 50.3% (never JUUL use). Across subgroups for which kappa statistics could be calculated, values ranged from 0.39 (lifetime tobacco product use) to 0.74 (non-Hispanic, white students).

Table 2.

Percent of Concordant and Discordant Responses to the Questions Assessing Lifetime Electronic Cigarette (E-Cigarette) Use and Lifetime Use of One or More E-Cigarette Devices

| Concordant | Discordant | Kappa | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 83.2 | 16.8 | 0.67 | (0.63–0.70) |

| Lifetime vapers | 68.5 | 31.5 | — | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 63.2 | 36.8 | 0.61 | (0.56–0.66) |

| Male | 74.4 | 25.6 | 0.73 | (0.69–0.77) |

| Race | ||||

| Nonwhite | 58.5 | 41.5 | 0.58 | (0.53–0.63) |

| White | 77.3 | 22.7 | 0.74 | (0.70–0.78) |

| Lifetime product use | ||||

| Traditional tobacco products | ||||

| No | 57.2 | 42.8 | 0.64 | (0.58–0.69) |

| Yes | 73.9 | 26.1 | 0.39 | (0.31–0.47) |

| Disposable, cig-a-like, or E-hookah | ||||

| No | 63.0 | 37.0 | 0.64 | (0.60–0.68) |

| Yes | 85.6 | 14.4 | — | |

| Vape pen or Ego | ||||

| No | 58.4 | 41.6 | 0.64 | (0.59-0.68) |

| Yes | 76.5 | 23.5 | — | |

| JUUL | ||||

| No | 49.7 | 50.3 | 0.59 | (0.50–0.67) |

| Yes | 71.6 | 28.4 | — | |

| Other pod-based system | ||||

| No | 55.5 | 44.5 | 0.60 | (0.56–0.65) |

| Yes | 80.6 | 19.4 | — | |

| Mods or APVs | ||||

| No | 62.0 | 38.0 | 0.66 | (0.62–0.70) |

| Yes | 75.1 | 24.9 | — | |

APV = advanced personal vaporizers, CI = confidence interval.

Discussion

When asked about e-cigarette use using the question “Have you ever tried an e-cigarette, even one or two puffs?”, 35.8% of the sample endorsed lifetime use. However, when the use of specific e-cigarette devices was assessed, an additional 15.5% endorsed lifetime e-cigarette use (51.3% of the total sample). In total, there was only 66.6% agreement between the two operational definitions of e-cigarette use. Importantly, 31.5% of lifetime vapers did not endorse lifetime “e-cigarette” use.

With regard to user characteristics associated with misclassification, females, those identifying as a race other than non-Hispanic white, and those lacking experience using traditional tobacco products, Disposable e-cigarettes, cig-a-likes, or E-hookahs; vape pens; JUULs; or other pod-based systems were more likely to endorse lifetime vaping but not lifetime e-cigarette use. As anticipated, rates of providing discordant responses ranged across these subgroups of interest. Discordant responses were lowest among users of disposable, cig-a-like, and E-hookah devices (14.4%), suggesting that youth are more likely to consider these types of devices to be e-cigarettes. Discordant responses were highest among JUUL users (28.4%), suggesting that JUULs are less likely to be viewed as e-cigarettes. This finding is especially noteworthy given that JUULs were the most commonly used device in our sample.

Overall, the study findings suggest that asking about e-cigarette use, broadly defined, leads to an underestimation of actual use compared to assessing lifetime use of a range of different e-cigarette devices. Conversely, assessing the use of specific e-cigarette devices may yield more accurate rates of use.

The study findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, the study relied on self-report data, which can be susceptible to biased reporting, and focused on two high schools in Connecticut, which may limit generalizability. Second, although the question assessing lifetime “e-cigarette” use was accompanied by a picture of all of the e-cigarette devices assessed in the study, no definition of e-cigarette use was provided. Although a clear definition may help to clarify for participants what exactly constitutes a device being classified as an “e-cigarette” (especially in combination with a picture[s]), additional research is needed to determine how best to construct and present such a definition; no standard definition exists in the field. Of note, some common definitions may add to participants’ confusion rather than resolve it. For example, referring to e-cigarettes as “electronic nicotine products8” may lead to underestimates in prevalence rates among adolescents who do not use nicotine e-liquid, incorrectly believe that they do not use nicotine (although they do), or who are uncertain.9 Further, using definitions that provide example devices (eg, vape pens, mods) or brands (eg, NJOY, Blu)4 may lead to underestimates of use among adolescents who do not see the device or brand that they use listed. This may be especially problematic when popular devices or brands are not included in the exemplar list. For example, the 2017 National Youth Tobacco Survey4 omitted the most popular e-cigarette brand in America at the time (JUUL10) from their list of examples. Fourth, when assessing lifetime e-cigarette and device use, participants were forced to choose between response options of “no” and “yes.” Future research is needed to evaluate how allowing adolescents to indicate uncertainty about product use (eg, a response option of “I don’t know”) affects prevalence estimates. Finally, the majority of youth (73.7%) endorsed using more than one e-cigarette device in the current study. As such, we were not able to directly compare rates of underreporting e-cigarette use by device type due to restricted statistical power; rates of endorsing lifetime use of one device were less than 4.0% for all devices except JUUL (18.3%). Future research could address this issue by examining misclassification among a larger sample of single-device users or among users who prefer a single device.

In summary, this study suggests that assessing adolescents’ use of specific e-cigarette devices in surveys likely yields more accurate results than assessing the use of e-cigarettes, broadly defined. Although the study findings need to be replicated in a nationally representative sample, researchers are encouraged to consider assessing the use of specific types of e-cigarettes to obtain more reliable use estimates. In addition, regulatory efforts that require all e-cigarette devices to be clearly labeled as “e-cigarettes” may help ensure that adolescents, especially those who were more likely to underreport lifetime e-cigarette use (eg, females, non-white students), recognize what devices constitute e-cigarettes.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number P50DA036151 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the FDA.

Declaration of Interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the current study.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all participants who contributed to this work.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/2016_SGR_Full_Report_non-508.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 20112016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(23):597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miech R, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. What are kids vaping? Results from a national survey of US adolescents. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):386–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Historical National Youth Tobacco Survey Data and Documentation; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/data/index.html. Accessed July 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2018. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018–054382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Delnevo CD, Gundersen DA, Manderski MTB, Giovenco DP, Giovino GA. Importance of survey design for studying the epidemiology of emerging tobacco product use among youth. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson AL, Villanti AC, Glasser AM, Pearson JL, Delnevo CD. Impact of question type and question order on tobacco prevalence estimates in US young adults: a randomized experiment. Nic Tob Res. 2018;1:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. United States Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Tobacco Products. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files, Wave 4 Questionnaire; 2017. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/files/NAHDAP/PATH_Study_Wave4_Data_Collection_Instruments_English_and_Spanish.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2018.

- 9. Morean ME, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S. Nicotine concentration of e-cigarettes used by adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:224–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carver R. Juul exceeds 60 percent market share for e-cigs. Winston-Salem Journal; 2018. https://www.journalnow.com/business/juul-exceeds-percent-market-share-for-e-cigs/article_1fd229f1-df7d-5436-ac90-9263c418dc1c.html. Accessed July 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]