Abstract

The measurement of cervical dilation of a pregnant woman is used to monitor the progression of labor until 10 cm when pushing begins. There is anecdotal evidence that labor tracks across repeated pregnancies; moreover, no statistical methodology has been developed to address this important issue, which can help obstetricians make more informed clinical decisions about an individual woman’s progression. Motivated by the NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study (CPS), we propose new methodology for analyzing labor curves across consecutive pregnancies. Our focus is both on studying the correlation between repeated labor curves on the same woman and on using the cervical dilation data from prior pregnancies to predict subsequent labor curves. We propose a hierarchical random effects model with a random change point that characterizes repeated labor curves within and between women to address these issues. We employ Bayesian methodology for parameter estimation and prediction. Model diagnostics to examine the appropriateness of the hierarchical random effects structure for characterizing the dependence structure across consecutive pregnancies are also proposed. The methodology was used in analyzing the CPS data and in developing a predictor for labor progression that can be used in clinical practice.

Keywords: change point, consecutive pregnancies, individualized predictions, labor curves, Markov chain Monte Carlo

1 |. INTRODUCTION

During labor and delivery, a pregnant woman’s cervix, the opening to the uterus, dilates (opens). The measurement of cervical dilation is used to monitor the progression of labor (labor curve) until 10 cm when pushing begins. Thus, an understanding of each woman’s labor curve is very important in obstetric practice. These women enter the hospital at different centimeters of cervical dilation; hence, analyzing these data is difficult since there is no clearly defined time zero. Recent statistical methodology has been developed to address the analytical challenges for such data when only a single labor curve is observed on each woman.1 Although it has not been formally studied, there is anecdotal evidence that labor progression tracks across repeated pregnancies. If this is true, labor progression from previous pregnancies may help obstetricians make more informed clinical decisions about or predict future labor curves for an individual woman. New statistical methodology is required to address this important medical issue.

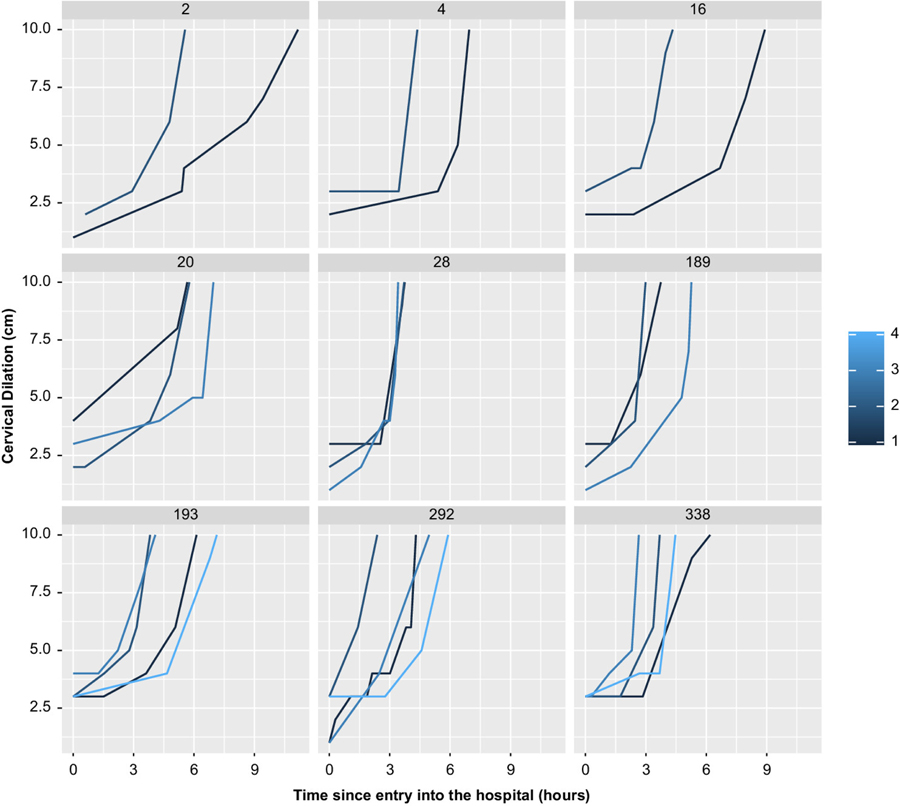

Motivated by the NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study (CPS), a unique cohort study that collected labor data on 51 086 women, we propose new methodology for analyzing labor curves across consecutive pregnancies. In the CPS study, the labor curve is measured on each women through her repeated pregnancies over a 9-year period. All women have at least two pregnancies by design (they were included in the retrospective study only if they had at least two pregnancies over this interval). Figure 1 shows the labor curves (the cervical dilation measurements in centimeters plotted against hours after arrival to the hospital) for a sample of nine women with two to four pregnancies each. It is unclear how similar these labor curves are across the same woman. More similar labor curves across a woman would suggest an increase in predictive ability by incorporating dilation measurements from previous pregnancies.

FIGURE 1.

Labor curves per pregnancy for a sample of nine women

Thus, the important scientific questions of interest along with the appropriate methodological development include: (i) how correlated are labor curves across individual women, and does this correlation persist after covariate adjustment? This is important for understanding the biology of labor progression; (ii) does using previous pregnancy labor measurements help obstetricians in predicting subsequent labor curves? Does it help in predicting the time to full dilation? Predicting a women’s progression through labor may be important for appropriately managing the final stages of her pregnancy.

Modeling labor progression in a single pregnancy has been studied by different authors, including but not limited to References 1–5. In modeling labor progression, the majority of authors have modeled time backward, where time zero is the time at delivery or full dilation (10 cm). However, not all women reach full dilation; hence, inferences may be biased given that those who do not reach full dilation are always excluded. In addition, using the backward time method cannot lead to meaningful predictions of future labor progression. In 2014, McLain and Albert proposed a more appropriate method for dealing with time zero. In their approach, the observed time from when a women arrives at the hospital is rescaled by some factors such that the time zero for all women is when they are expected to reach 2 cm of cervical dilation. The 2-cm criterion was based on the fact that women usually have a c-section after 2 cm. Thus, this method includes all women whose labor is terminated before full dilation of 10 cm. Moreover, predictions are more meaningful, given that the time is measured forward (from time zero when a woman reaches 2 cm through the last cervical dilation measurement).

Based on our knowledge, no work has been done on modeling labor across a woman’s consecutive pregnancies. In this article, we develop a model for labor progression in consecutive pregnancies. We propose a hierarchical random effects model with a random change point that characterizes repeated labor curves within and between women. A change point model was motived by early work of Friedman,6,7 who showed that labor in the first stage (from onset of labor to full cervical dilation) is divided into two main phases. The first phase, known as “latent,” is characterized by gradual or slower cervical change, while the second phase, known as “active,” is characterized by rapid or faster cervical change. In addition, we propose diagnostic measures to examine the appropriateness of the correlation structure for this model. We employ Bayesian methodology for parameter estimation and predictions. The Gaussian quadrature and the Monte Carlo EM algorithm methods employed, for instance, by McLain and Albert1 are computationally very intensive. This computational burden grows exponentially with the number of random effects in the model. In addition, the bootstrap method they employed to estimate the standard errors adds to the computational burden. The Bayesian methods, on the other hand, are less computational in that they do not use direct integration and standard error estimation is more easily done.

Section 2 presents the formulation of the random effects change point model, while the associated likelihood, priors, and posterior distribution are specified in Section 3. Section 4 shows the parameter estimation procedures from their full conditionals, diagnostics, and the model assessment tools, while Section 5 shows how individualized predictions are carried out. Section 6 describes the software used in this article. Section 7 presents an application of the proposed model (fitting and predictions) to the CPS data and predictions, and Section 8 shows the results of a simulation study. A discussion follows in Section 9.

2 |. MODEL DEVELOPMENT

Let denote the L-variate response vector for ith subject (i = 1, … , n), where yil, l = 1, … , L, is an nil × 1 vector of cervical dilation measurements for the lth pregnancy measured at time tilj, j = 1, … , nil, and where time is measured from when the woman enters the hospital at potentially different dilation values. To recalibrate the time variable so it can be interpreted in a sensible way, we rescale the time tilj by the factor Δil such that time zero is the time when a woman is expected to reach a dilation of K = 2 cm, which can happen before or after arriving at the hospital.1 Thus, the mean dilation is K = 2 cm when silj = tilj− Δil = 0, where silj is the rescaled time for the jth measurement of the lth pregnancy on the ith woman. Also, let cil be the change point reflecting the time in which the labor progresses from the first to second phase for the lth pregnancy on the ith woman.

Because we have repeated measures and each woman has multiple pregnancies, we propose a model that incorporates dependencies across and within women (Equation 1). In particular, we include woman- and fetus-within-woman- specific random effects to allow for heterogeneity between and within women, respectively. In this model, we assume that the outcome follows a normal distribution conditional on these random effects.

| (1) |

where , , , and cil = c + bic + bilc. The parameters β1, β2, Δ, and c represent the mean prechange point slope, postchange point slope, time-scaling factor, and change point, respectively. The random effects bi1, bi2, biΔ, and bic measure the between-woman variation (woman-specific) in the prechange point, postchange point, time-scaling factor, and change point, respectively, while bil1, bil2, bilΔ, and bilc in the same order reflect the within-woman variation (fetus-within-woman-specific). The correlation between labor parameters (slopes, change point, and time when entering the hospital) across a woman is for each component of the labor curve p. This hierarchical random effects’ structure imposes strong assumptions on the correlation between consecutive pregnancies. Specifically, this structure imposes an exchangeable correlation between repeated pregnancies on the same woman. An alternative correlation structure is one where the correlation is a function of the time between pregnancies. In Section 7.1.1, we propose model diagnostics to examine the adequacy of the nested random effects structure.

The random effects and the error term (ϵils) are assumed to follow Gaussian distributions, that is, , , and . Furthermore, bi and bil are assumed to be independent of each other and also independent from the error term, ϵils. Including woman- and fetus-within-woman-specific covariates in the model above is straightforward. For instance, if we define x and βx to be a set of covariates and their associated regression coefficients, respectively, then , , , and , where βx1, βx2, βxΔ, and βxc the effect of covariates x on the mean prechange point slope, postchange point slope, time-scaling factor, and change point, respectively. The fixed effect regression coefficients are subject-specific where the effect of a covariate is on individual level labor progression rather than on the population level.8

To estimate the parameters of interest using Bayesian methods, we specify the priors for the parameters and then the posterior inference is obtained by using the likelihood to convert prior uncertainty into posterior probability statements. In the next section, we give the likelihood, priors, and posterior distribution for the proposed methodology.

3 |. LIKELIHOOD, PRIOR, AND POSTERIOR DISTRIBUTION

3.1 |. Likelihood

Let be the parameters of interest and Σ = (Σ1, Σ2) denote the parameters associated with the random effects. Let y be the observed data and b be the combined random effects. Under the normal random effect model, the likelihood for the proposed model is

| (2) |

where .

3.2 |. Prior specification and posterior distribution

Let , , μΔ, μc and , , , denote the means and variances for β1, β2, Δ, and c, respectively. For the proposed model, we assumed normal proper priors for the fixed parameters , , ,. The variance-covariance matrices of the random effects (Σ1, Σ2) were assumed to follow inverse Wishart (IW) distributions: , , where ν1 and ν2 are the degrees of freedom and Λ1 and Λ2 are symmetric, positive-definite scale matrices, while for the error variance , an inverse gamma (IG) was assumed, that is, , where ζ and ω are the shape and scale hyperparameters, respectively. IW and IG distributions are conjugate priors for the variance-covariance matrix in the multivariate and univariate normal likelihoods, respectively.9 However, these assumptions may be difficult to verify or may not be suitable for the problem at hand. Thus, we performed prior sensitivity analysis employing nonconjugate priors (see Table 5 in Supplementary Material).

Given the prior distributions of all parameters and the observed data, the joint posterior distribution for the proposed model can be expressed as

| (3) |

where L(θ, Σ|b,y) is specified by Equation 0.

In Section 4, we show how each parameter or a block of parameters was estimated from the joint posterior distribution.

4 |. ESTIMATION, DIAGNOSTICS, AND MODEL ASSESSMENT

In this section, we show parameter estimation procedures, convergence diagnostics, and model adequacy assessment tools. The parameters of interest are estimated by drawing random variates from their full conditional posterior distributions, which are determined by averaging the posterior distribution (Equation 0) over or integrating out the remaining parameters (see Supplementary Material: Full Conditionals). Gibbs sampling10 with some Metropolis-Hasting (M-H)11,12 steps was used to draw samples from their conditional distributions. These Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are fully implemented in WinBUGS13 and JAGS14 software. Given the complexity of our proposed model, we employed a hierarchical centering method to improve convergence and the mixing of the chains.15,16 Thus, bil was centered at bi, while bi was centered at the fixed parameters or intercepts (β1, β2, Δ, c).

To determine whether the MCMC Markov chains converged to the stationary or target distribution(s) and to determine the burn-in, we examined the trace and density plots for proper mixing of the chains.17 In addition, the Gelman and Rubin multiple sequence test18 was used, where a value above 1.1 indicated nonconvergence.

To compare different models with different covariate effects, we employed the deviance information criterion (DIC).19 Let θ denote the vector of model parameters and y denote the observed data, then the deviance D(θ) is defined as

where f(y|θ) is the likelihood function and h(y) is a standardizing function of the data alone.9 The DIC is then computed using: , where is the posterior mean of θ and is the effective number of parameters that measure model complexity, with defined as the posterior mean deviance and is the deviance at the posterior mean. A model with a smaller value of DIC is better.19

The model adequacy or fit was assessed using posterior predictive checks.20 Let H be the assumed model and θ be the associated unknown model parameters. Also, T denotes a test statistic, a function from data space to the real numbers. Furthermore, let y and yrep be the observed and replicated data, respectively. Then the distribution of the future observation or replicated data yrep, known as the posterior predictive distribution, is given by

where P(θ) is the prior distribution of θ. The observed value of T, T(y) (standardized Pearson residuals), was then plotted against the distribution of T(yrep). The corresponding tail-area probability is

which is called the posterior predictive or Bayesian P-value.21 A P-value around 0.5 indicates a good fit.

5 |. INDIVIDUALIZED PREDICTIONS

In this section, we focus on estimating the expected labor curve for a woman based on her previous pregnancy information. In particular, based on our proposed model fit on a sample of consecutive pregnancy data for m women, we are interested in predicting the labor curve for a new woman who has provided a set of cervical dilation measurements on some parts of the pregnancies. Let Dm be full data collected on all pregnancies of m women. Now suppose we have a new (m + 1)th woman who has provided some measurements on previous pregnancies or the current pregnancy, all summarized as ym+1. Given these data, the predictive distribution for a new observation from this distribution with random effects and parameters is

| (4) |

Thus, given the random effects for a new woman, which are estimated from the partial data (testing set) provided by this woman and the parameters estimated from the full data (training set) of the m women, we are able to predict an individual woman’s future curve. The estimation was done using MCMC methods with help of cut () function in WinBUGS.22 The cut () function ensures that the parameters from one model do not feed back into the other model.

To assess the predictions made by our model, we used a training dataset of 500 women with at least two measurements in each pregnancy and a testing dataset of 500 randomly chosen women with two pregnancies and at least five measurements during the second pregnancy. The goal was not just to predict future dilation measurements but to predict time to reaching full 10 cm dilation during the second pregnancy from earlier measurements on these women. The time to reaching 10 cm was estimated by inverse regression using the predicted labor curve based on the proposed model (ie, using the predicted labor curve, we find the value of scaled time, where the curve first crosses 10 cm).

We had two scenarios to compare in our predictions. In the first scenario, we used only the second pregnancy information (ie, the first four, five, six, or seven measurements) to predict future dilation measurements (the fifth, sixth, seventh, or eighth through the last measurement of the second pregnancy) and time to full 10-cm dilation. In the second scenario, the predictions were done with the addition of the first pregnancy dilation data. We then computed the prediction mean-squared error (PMSE) and predictive median absolute deviation (MAD) for each of the scenarios as follows.

For future dilation measurements,

where n is the sample size of the testing dataset, yilj and are the observed and predicted dilation values for the ith subject on the lth pregnancy, respectively, and k = 4, 5, 6, or 7 is the number of observed measurements in the 2nd pregnancy.

For time to 10-cm dilation,

where Til and are the observed and predicted times in hours to full 10-cm dilation for the ith subject on the lth pregnancy, respectively. In the case of skewed data, MAD is preferred to PMSE; otherwise, they should lead to the same conclusions. A smaller PMSE or MAD indicates a better prediction model.

6 |. SOFTWARE

In this section, we describe the software employed to achieve the desired outputs. The Bayesian sofware employed includes WinBUGS, JAGS, and STAN. WinBUGS is one of the first statistical software for Bayesian analysis using MCMC methods. It is based on the Bayesian inference using Gibbs sampling (BUGS) project started in 1989 by a team of UK researchers at the MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, and Imperial College School of Medicine, London.13 WinBUGS can be used as a standalone application but can also be integrated with R statistical software using the R2WinBUGS package in R. It has built-in functions like the cut () function, which ensures that the parameters from one model do not feed back into the other model. The last version of WinBUGS was version 1.4.3, released in August 2007, and it remains available as a stable version for routine use but is no longer being developed.13 In this study, we used WinBUGS for predictions because of the cut () function.

Just another Gibbs sampler (JAGS) is also a program for simulation from Bayesian hierarchical models using MCMC, developed by Martyn Plummer.14,23 It is compatible with WinBUGS through the use of a dialect of the same modeling language, BUGS, and can be controlled from within another program like R via the rjags package. However, it does not have the cut () function. The advantage it has over WinBUGS is that it is used on Linux platforms like Biowulf (http://biowulf.nih.gov), which was used in this study for simulations and data analysis.

Finally, STAN24 software, which uses Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) methods, was employed in this study for prior sensitivity analysis. HMC is a MCMC method that uses the derivatives of the density function being sampled to generate efficient transitions spanning the posterior (see the work of Betancourt and Girolami25 for more details). The advantage of STAN over WinBUGS and JAGS is that it can work with nonconjugate priors.

7 |. DATA ANALYSIS AND PREDICTIONS

7.1 |. Data analysis

In this section, we present the analysis of the CPS data introduced in Section 1. Our goal is to determine the factors associated with labor progression as well as to predict individualized labor curves given previous pregnancy information. We considered a subset of consecutive pregnancy data, that is, for 1000 women with a total of 2084 pregnancies (see summary in Table 1). Although all subjects included had at least two pregnancies, not all subjects had labor data as shown by a minimum number of pregnancies per subject in Table 1. The covariates of interest were the number of live births before the current pregnancy (parity), time in years between consecutive pregnancies (gap time), and whether labor was induced or not. Parity was treated as ordinal or continuous, while gap time and induced labor were treated as categorical. Gap time had three levels (ie, no prior information or pregnancy, above median (baseline), and below median) and induced labor two [induced and not induced (baseline)] levels. The median gap time for this sample of women was 2.29 years (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics for the study sample

| Variable | Total | Mean | Minimum | Median | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 1000 | — | — | — | — |

| Number of pregnancies | 2084 | — | — | — | — |

| Pregnancies per woman | — | 1.59 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Parity | — | 1.60 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Age in years | — | 27.4 | 15 | 27 | 44 |

| Gap time in years | — | 2.50 | 0.75 | 2.29 | 7.06 |

| Labor induced | N | % | |||

| Induced | 1412 | 62.8 | |||

| Not induced | 672 | 32.3 | |||

| Mode of delivery | N | % | |||

| Spontaneous (vaginal) | 1843 | 88.4 | |||

| C-section | 241 | 11.6 |

We fit our proposed model (Equation 1) (with both woman-specific and fetus-within-woman-specific random effects) and a reduced model (without woman-specific random effects). The following priors were considered for the different parameters: intercepts (β1, β2, Δ, c) were assumed to follow normal distributions (ie, β1, β2, Δ, c ~ N (0, 106)), error variance was assumed to follow IG (ie,), variance-covariance matrices for the between and within random effects were assumed to follow , where Iq indicates an q × q identity matrix, , , and coefficients were each assumed to follow a normal distribution with mean zero and variance of 106.

The MCMC was run for 200 000 iterations with the first 50 000 discarded as burn-in. The models were fit in JAGS (version 3.4.0) and its R interfaces rjags and R2jags. The Gelman and Rubin multiple sequence test18 indicated that all parameters estimated converged. The diagnostic plots further indicated proper mixing of the chains and convergence to the stationary distributions (see Figures 1–4 in Supplementary Material).

The posterior estimates of the regression coefficients, standard errors (SD), and their 95% credible intervals (CI) using the reduced and proposed models are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Analysis of CPS data using the reduced and proposed models (1000 women)

| Reduced Model (Without

Between-Subject Random Effects) |

Proposed Model (With

Between-Subject Random Effects) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

| Intercept | ||||||

| β1 | 0.68 | 0.15 | (0.51, 1.03) | 0.58 | 0.05 | (0.47, 0.67) |

| β2 | 1.74 | 0.49 | (0.51, 2.32) | 2.52 | 0.19 | (2.18, 2.81) |

| Δ | −2.12 | 0.43 | (−2.89, −1.44) | −2.05 | 0.30 | (−2.52, −1.32) |

| c | 5.18 | 0.89 | (3.93, 7.20) | 3.32 | 0.61 | (1.97, 4.24) |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0.00 | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.00 | 0.01 | (−0.01, 0.03) | |

| 0.41 | 0.08 | (0.13, 0.51) | 0.40 | 0.04 | (0.31, 0.46) | |

| ΔParity | −0.23 | 0.05 | (−0.33, −0.14) | −0.26 | 0.07 | (−0.38, −0.12) |

| cParity | 0.04 | 0.11 | (−0.18, 0.26) | 0.29 | 0.08 | (0.10, 0.44) |

| Gaptime | ||||||

| −0.05 | 0.02 | (−0.09, −0.01) | −0.04 | 0.02 | (−0.09, 0.00) | |

| 0.00 | 0.02 | (−0.05, 0.05) | 0.01 | 0.02 | (−0.04, 0.05) | |

| −0.43 | 0.18 | (−0.89, −0.12) | −0.60 | 0.15 | (−0.86, −0.34) | |

| −0.42 | 0.25 | (−0.89, 0.04) | −0.32 | 0.14 | (−0.59, −0.03) | |

| ΔNo data | −0.11 | 0.20 | (−0.51, 0.24) | −0.31 | 0.25 | (−0.90, 0.15) |

| ΔBelow median | −0.61 | 0.25 | (−1.08, −0.13) | −0.70 | 0.24 | (−1.16, −0.22) |

| cNo data | 0.62 | 0.24 | (0.14, 1.09) | 0.95 | 0.36 | (0.31, 1.64) |

| cBelow median | 0.39 | 0.31 | (−0.18, 1.00) | 0.59 | 0.37 | (−0.08, 1.31) |

| Labor induced | ||||||

| −0.30 | 0.13 | (−0.58, −0.17) | −0.22 | 0.03 | (−0.28, −0.17) | |

| 0.93 | 0.45 | (0.43, 2.28) | 0.46 | 0.10 | (0.30, 0.64) | |

| ΔInduced labor | 0.94 | 0.26 | (0.47, 1.43) | 0.87 | 0.23 | (0.35, 1.25) |

| cInduced labor | 2.37 | 0.82 | (0.22, 3.51) | 3.59 | 0.46 | (2.89, 4.67) |

| Between variance | ||||||

| — | — | — | 0.02 | 0.00 | (0.01, 0.02) | |

| — | — | — | 0.13 | 0.04 | (0.07, 0.23) | |

| Σ1Δ | — | — | — | 0.30 | 0.16 | (0.10, 0.70) |

| Σ1c | — | — | — | 0.27 | 0.12 | (0.10, 0.57) |

| Within variance | ||||||

| 0.05 | 0.02 | (0.03, 0.09) | 0.03 | 0.00 | (0.03, 0.04) | |

| 2.54 | 0.45 | (2.08, 3.99) | 2.51 | 0.21 | (2.00, 2.87) | |

| Σ2Δ | 13.46 | 2.28 | (9.51, 17.05) | 15.98 | 1.16 | (13.82, 18.29) |

| Σ2c | 6.59 | 1.33 | (3.85, 9.03) | 6.70 | 1.05 | (3.48, 8.28) |

| Intracluster correlation | ||||||

| — | — | — | 0.31 | 0.03 | (0.25, 0.38) | |

| — | — | — | 0.05 | 0.02 | (0.03, 0.09) | |

| ρ12Δ | — | — | — | 0.02 | 0.01 | (0.01, 0.04) |

| ρ12c | — | — | — | 0.04 | 0.02 | (0.01, 0.08) |

| Error variance | ||||||

| 0.65 | 0.07 | (0.57, 0.80) | 0.59 | 0.03 | (0.56, 0.69) | |

| Goodness of fit | ||||||

| DIC | 656130.3 | 145326.9 | ||||

| Bayesian P-value | 0.499 | 0.500 | ||||

Note:, , Σ1Δ, Σ1c are the diagonal elements of matrix Σ1, , , Σ2Δ, Σ2c are the diagonal elements of matrix Σ2; , ,.

Based on DIC, our proposed model (right of Table 2) fits the data better than the reduced model without woman-specific random effects. The results in Table 2 from fitting the proposed model indicated that all the covariates (parity, gaptime, and induced labor) adjusted for had a significant effect on labor progression. A full model with covariances is in the Supplementary Material (Table 1).

Parity played a significant role in labor progression during the second phase (postchange point slope), the time of the change point, and the time scaling factor (Δ). Specifically, a woman’s labor progressed faster during the second phase (postchange point slope) for higher parity than lower parity . In addition, women with higher parity came to the hospital later in labor than women with lower parity (ΔParity = −0.26). Furthermore, women with higher parity experienced their change point later in labor (cParity = 0.29) than those with lower parity.

Gap time significantly influenced labor progression during the second phase (β2), through the time-scaling factor (Δ) and the change point (c). Women with no information on gap time and whose gap time was below the median had their labor progress slower during the second phase than those whose gap time was above the median. In addition, women with gap time below the median came to the hospital later in labor than those whose gap time was above the median (ΔBelow median = −0.70). Furthermore, women with no information on gap time experienced their change point later in labor than those above the median (cNo data = 0.95).

Induced labor had a significant effect on labor progression. A woman who had labor induced had her labor progress faster in the second phase than one whose labor was not induced, while in the first phase, a woman who had labor induced had slower labor progression than one with normal labor. Furthermore, a woman whose labor was induced came to the hospital earlier (ΔInduced labor = 0.87) and experienced her change point later (cInduced labor = 3.59) in labor than a woman who had normal labor.

With the exception of the prechange point slope, the between-woman variances were much smaller than the within-woman variances, which indicated little correlation (as shown by the intracluster correlations, ie, between-woman variation divided by the sum of the within-woman and between-woman variations) between repeated pregnancies even after adjusting for parity, gap time, and whether labor was induced or not. The high correlation in the prechange point slope across repeated pregnancies suggests that early labor may be more influenced by the individual woman than by the particular fetus, while the reverse may be true for later labor. This interesting and important observation would not have been possible without the proposed model.

The posterior predictive checks (Figure 5 in Supplementary Material) and the Bayesian P-values (Table 2) indicated that the proposed model fit the data well. Moreover, the prior sensitivity analysis indicated that the results from the proposed model are not sensitivity to the choice of priors (see Prior Sensitivity Analysis section in Supplementary Material, Table 5).

7.1.1 |. Further model diagnostics: Correlation structure and residuals

We used the variogram to examine whether the hierarchical random effects used in the proposed model were consistent with the data. Specifically, we examined whether the correlation changed with gap time between pregnancies. We fit separate random effects models for the first and second pregnancies. The squared difference between the estimated random effects for pregnancies 1 and 2 (variogram) was plotted against the time between the two pregnancies (gap time) in years. The results (Figures 6–9 in Supplementary Material) showed no evidence of temporal trend. Thus, the exchangeable correlation structure is consistent with the proposed exchangeable correlation model. Although there is a literature on characterizing the correlation between curves in the functional data analysis,26,27 our approach differs from these other approaches in that the correlation is characterized through random effects governing woman-specific and fetus-within-woman effects.

In addition, we performed residual analysis, and the results showed no pattern in the residuals suggesting that the proposed model fit well (see Figures 10 and 11 in Supplementary Material).

7.2 |. Individualized predictions

The summaries in Table 3 show the predictive accuracy of the proposed model across the 500 women in the validation or testing sample for predicting both future cervical dilation measurements in the second pregnancy (right panel) and the time to full dilation (10 cm) (left panel). The first pregnancy data improve accuracy most substantially when the second pregnancy has fewer measurements. For instance, with only four dilation measurements in the second pregnancy, there is about a 70% and 44% (using PMSE) gain in predictive accuracy when first pregnancy information is included when predicting time to 10 cm and future cervical dilation measurements, respectively. However, when the number of observed dilation measurements increases to 7, the predictive accuracy is only 3% and 0.2% for time to 10 cm and future cervical dilation measurements, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Evaluating prediction of time to reaching 10 cm and future cervical dilation measurements using the proposed model

| Given Data | Time to Reaching 10 cm |

Future Dilation

Measurements |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMSE | MAD | PMSE | MAD | |

| Four observations | 601.09 | 4.96 | 10.62 | 1.75 |

| Four observations + first pregnancy | 354.89 | 4.39 | 7.40 | 1.68 |

| Five observations | 398.14 | 3.70 | 6.10 | 1.71 |

| Five observations + first pregnancy | 348.48 | 3.28 | 6.09 | 1.67 |

| Six observations | 173.53 | 2.97 | 4.51 | 1.36 |

| Six observations + first pregnancy | 118.18 | 2.49 | 4.35 | 1.27 |

| Seven observations | 116.91 | 3.48 | 4.10 | 1.32 |

| Seven observations + first pregnancy | 113.15 | 3.47 | 4.09 | 1.29 |

Abbreviations: MAD, median absolute deviation; PMSE, prediction mean-squared error.

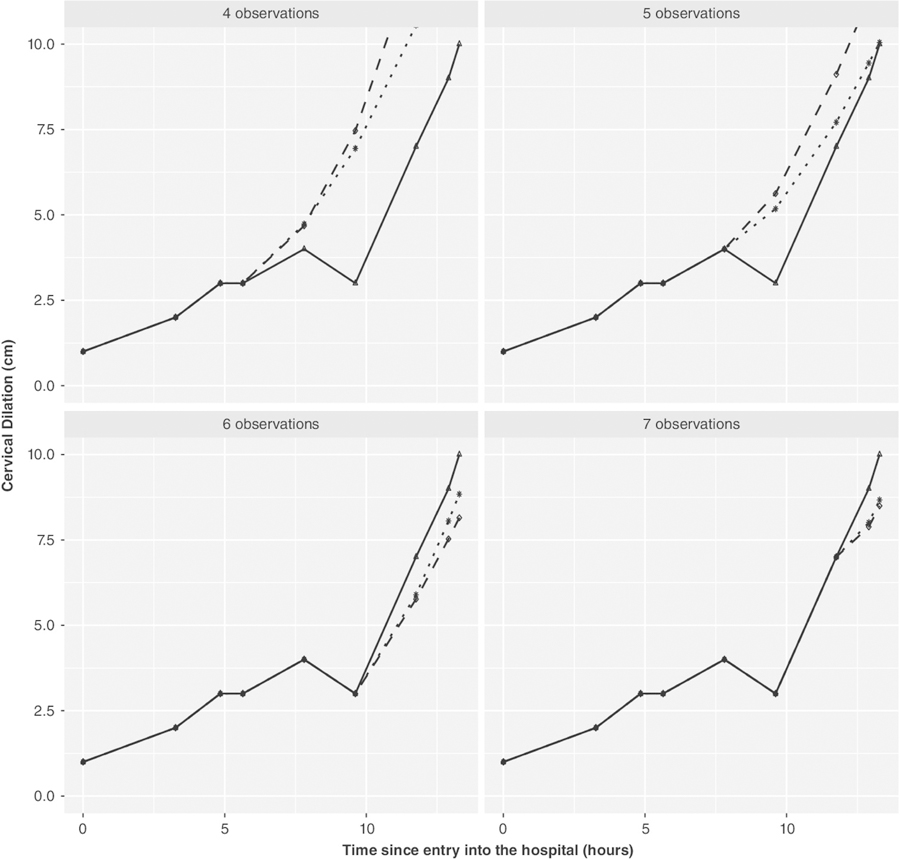

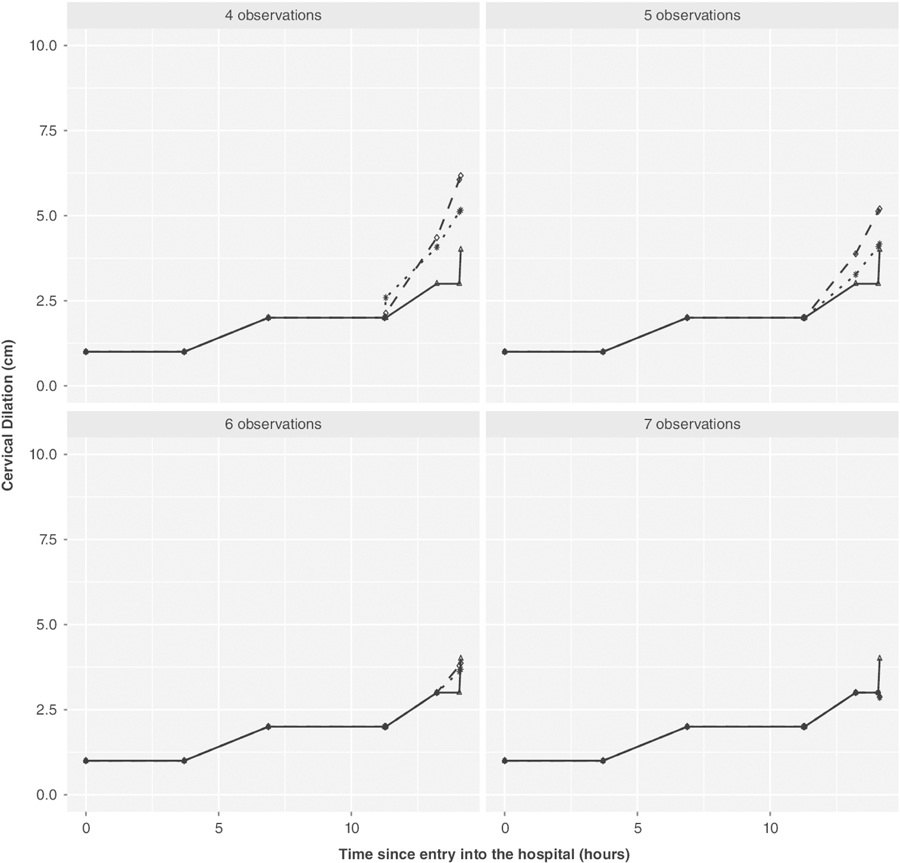

Figures 2 and 3 provide a visual demonstration on two women chosen at random from the 500 subjects (results for 18 other women are shown in the Supplementary Material: Figures 12–29). These plots demonstrate how the prediction varies as the number of measurements in the second pregnancy increases. These figures visually demonstrate what was seen in the full validation sample, namely, using prior pregnancy data is most useful in situations where the number of measurements in the current pregnancy is limited.

FIGURE 2.

First individual’s predicted labor curves given four to seven observations using the proposed model(adjusted for parity, induced labor, gaptime): the thick line with triangles indicates the observed labor curve for second pregnancy; the dotted line with stars and dashed line with circles indicate the predicted labor curve (future observations) when first pregnancy data are included and when not included, respectively

FIGURE 3.

Second individual’s predicted labor curves given four to seven observations using the proposed model (adjusted for parity, induced labor, and gaptime): the thick line with triangles indicates the observed labor curve for second pregnancy; the dotted line with stars and dashed line with circles indicate the predicted labor curve (future observations) when the first pregnancy data are included and when not included, respectively

8 |. SIMULATION STUDY

To evaluate our proposed methodology, we conducted a simulation study. We generated 1000 data sets of sample sizes n = 500 subjects. The examination times (tilj, j = 1, … , nil) for each pregnancy were those from the motivating data set. The random effects bi and bil were generated from multivariate normal distributions with mean vectors 0 and variance-covariance matrices Σ1 and Σ2, respectively. That is,

and

The error ϵil was simulated from with . In addition, we chose regression parameters as β1 = 0.388, β2 = 2.503, Δ = −1.404, and c = 6.385 for intercepts (prechange point, postchange point, time-scaling factor, an dchange point, respectively). The true values for all the variance and regression parameters were chosen based on fitting a simplified model (Supplementary Material in Table 2) without covariates to a subset (500 women) of the CPS data. Once the latent parameters b = (bi, bil) were generated from their respective distributions, we generated yil(t)|bi, bil using model (Equation 1) with K = 2. After generating the data, we fit our proposed model to each data set. For the MCMC sampling, we ran two chains of 150 000 iterations with 50 000 iterations of each chain used as burn-in period. For all parameters, we assumed priors similar to those used in the data analysis (Section 7).

The above simulation where we chose parameters that were similar to those in the motivating example resulted in nearly unbiased estimation (and reasonable coverage rates) for the fixed effect parameters but poorer performance for the random effect variance (Table 4). Additional simulations with a larger sample size (1000) and an increased number of repeat pregnancies per woman did not show substantial improvement in this performance. A closer examination showed that the resulting parameter estimate distributions were skewed for most of the variance components. Specifically, the histograms for the random effects estimates were skewed when the within-subject variation was larger than the between-subject variation, explaining the poor coverage rates in this case (data not shown). However, for the situation where the between-subject variation is larger than the within-subject variation (most often the case in practice), the performance of the random effect estimation was substantially improved (see Table 4 in Supplementary Material). In this later case, the parameter estimate distributions for the variance components obtained from the simulation were substantially less skewed (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Simulation results using 500 women

| Parameter | Truth | Estimate | MCSD | SD | CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepts | |||||

| β1 | 0.388 | 0.379 | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.95 |

| β2 | 2.503 | 2.496 | 0.114 | 0.094 | 0.95 |

| Δ | −1.404 | −1.291 | 0.232 | 0.240 | 0.91 |

| c | 6.385 | 6.236 | 0.249 | 0.248 | 0.92 |

| Between variance | |||||

| 0.019 | 0.046 | 0.021 | 0.224 | 0.99 | |

| 0.163 | 0.177 | 0.072 | 0.033 | 0.93 | |

| Σ1Δ | 0.336 | 0.287 | 0.161 | 0.076 | 0.97 |

| Σ1c | 0.596 | 0.349 | 0.223 | 0.132 | 0.38 |

| −0.002 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.99 | |

| −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.017 | 0.010 | 0.99 | |

| −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.025 | 0.093 | 0.99 | |

| 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.074 | 0.031 | 0.95 | |

| −0.008 | 0.027 | 0.086 | 0.038 | 0.89 | |

| 0.064 | −0.041 | 0.134 | 0.058 | 0.64 | |

| Within variance | |||||

| 0.024 | 0.071 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.01 | |

| 2.836 | 2.914 | 0.210 | 0.168 | 0.91 | |

| Σ2Δ | 12.258 | 12.681 | 1.190 | 1.093 | 0.93 |

| Σ2c | 7.992 | 8.752 | 1.283 | 1.483 | 0.92 |

| −0.059 | −0.082 | 0.045 | 0.041 | 0.92 | |

| −0.168 | −0.308 | 0.086 | 0.104 | 0.74 | |

| −0.172 | −0.159 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.94 | |

| 1.843 | 1.167 | 0.542 | 0.674 | 0.84 | |

| −0.787 | −0.059 | 0.554 | 0.696 | 0.83 | |

| −0.198 | −0.343 | 1.022 | 1.189 | 0.95 | |

| Error variance | |||||

| 0.531 | 0.541 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.95 |

Note:, , Σ1Δ, Σ1c, , , Σ2Δ, Σ2c, are defined as in Table 2; while , , , , ⵈ, are covariances.

Abbreviations: CP, coverage probability; MCSD, Monte Carlo standard deviation, SD, posterior standard deviation.

To determine the effect of the biased varaince component estiamtion on prediction, we simulated labor data from the proposed model with the true parameters given in Table 4. We simulated data for 500 women with two pregnanacies and with follow-up times resampled from the CPS data limited to pregnancies with at least two measurements in the first pregnancy and at least five measurements in the second pregnancy. We then compared predicted values for subsequent second pregnancy measurement values using the true and the mean estimated parameter values (obtained from Table 4). A Bland Altman plot28 was used to assess the agreement between the two sets of predicted dilation values (Figure 30 in Supplementary Material). The figure shows that the average predictions between the two approaches are near zero and that over 95% of predictions are within the interval of (−0.40 cm, 0.46 cm). A similar Bland Altman plot was used to assess agreement between the two predictions for the time to reaching 10 cm (Figure 31 in Supplementary Material). The plot demonstrates very good agreement between the two predictors [the mean difference is near zero and 95% of differences between predictors are within the interval of (−2.07 hours, 1.96 hours)]. These results illustrate that the small amounts of bias for the variance components in our model have little impact on prediction.

9 |. DISCUSSION

We proposed a Bayesian hierarchical change point model for modeling and predicting future labor curves in consecutive pregnancies. The use of a Bayesian approach that is fully implemented in BUGS software and computationally more flexible than maximum likelihood methods makes our methodology very user-friendly. In addition, standard errors and predictions are easy to obtain.

Data analysis results showed that induced labor had a significant effect on labor progression. Women who were induced had their labor progress faster than those who were not induced during the second phase. Parity also played a significant role in the second phase of labor, where women with higher parity had a faster labor progression than those with lower parity.

The simulation study results indicated that the Bayesian approach taken has good frequentist properties (nearly unbiased estimation). However, variance components were slightly biased. We redid simulations with more measurements and a larger number of women and found a similar degree of bias for the variance components. Furthermore, with additional simulation studies, we showed that the small amounts of bias for the variance components had only a small effect on individual predictions.

The model shows that dilation change in early labor is correlated across repeated pregnancies but that no other feature is. The fact that the first phase slope is the only feature of the labor curve that has sizable within-woman correlation has interesting biological implications. It suggests that woman-intrinsic factors may influence labor progression early in labor, while fetus-specific factors are influential later in labor.

Moreover, the predictions indicate that prior pregnancy information significantly increases accuracy of the prediction of the time to full- and future cervical-dilation for the current pregnancy. The gain in predictive accuracy is more prominent when fewer number of dilation measurements in the current or second pregnancy have been observed or during early stages of labor, a result that has important clinical implications since accurate prediction is most useful early in the labor process. However, we observed little gain in predictive power when more dilation measurements were obtained (after six or seven observed measurements).

The proposed model was compared with a reduced one without woman-specific random effects. Although this reduced model fits the data well based on Bayesian P-values, the DIC showed that the proposed model is better. In addition, we performed a sensitivity analysis, that is, fit our model to data without c-section and the results showed no meaningful differences (see Table 3 in Supplementary Material).

The effect of rounded dilation measurements was investigated in the earlier work of McClain and Albert.1 They did a simulation investigating the effect of round-off error in a similar model without repeated labor curves on the same individual. The results showed that there was little effect of rounding. Hence, there are no major effects on the estimates using the proposed model treating the dilation data as continuous.

Although Bayesian estimation provides a framework for incorporating monotonicity in the dilation measurements over time, incorporating this constraint is difficult since it would need to be placed on the individual level (random and fixed effects). There have been recent articles that have done this,29 but estimation would be difficult using publicly available software such as JAGS or STAN. Furthermore, we would not expect constrained estimation to provide much benefit since there is strong empirical evidence that the individual patterns are monotonically increasing (whereas constrained estimation would be most advantageous in situations where the monotonicity was more empirically ambiguous).

Our proposed methodology would be very useful in many other applications. For example, von Hippel-Lindau syndrome is a genetic disease in which affected individuals show multiple tumors that can be followed longitudinally to assess tumor progression. Symptomatic individuals will have multiple lesions, but the time of onset for many of the tumors is unknown. Also, tumor growth can often be represented with a change point model, where tumor progression is more rapid after an initial period of less rapid growth. In this application, it is of interest to predict future tumor growth from the same tumor as well as from more distant tumors. Another example would be the study of prostate specific antigen (PSA) among males who are siblings. It is well known that longitudinal biomarkers of PSA for predicting prostate cancer can be described using longitudinal random effects’ models with random change points. It may also be true that subjects who are accrued later in tumor progression may not have a time zero for tumor initiation. Interest may be on estimating the association of tumor progression across sibling pairs. Furthermore, researchers may be interested in using siblings to more efficiently predict an individual’s PSA trajectory.

The proposed methodology focused on a single labor outcome or biomarker (ie, cervical dilation). Future research will address incorporating additional labor outcomes, including c-section (multivariate), in the analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (http://biowulf.nih.gov). The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. We thank the referees for their constructive comments that led to an improved article.

This class file was developed by Sunrise Setting Ltd, Torquay, Devon, UK. Website: www.sunrise-setting.co.uk

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLain AC, Albert PS. Modeling longitudinal data with a random change point and no time-zero: applications to inference and prediction of labor curve. Biometrics. 2014;70:1052–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conell-Price J, Evans JB, Hong D, Shafer S, Flood P. The development and validation of a dynamic model to account for the progress of labor in the assessment of pain. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1509–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Landy HJ, Branch DW, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1281–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arunajadai SG. A nonlinear model for highly unbalanced repeated time-to-event data: application to labor progression. Stat Med. 2010;29:2709–2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmi A, Ratcliffe SJ, Parry S, Guo W. A B-Spline based semiparametric nonlinear mixed effects model. J Comput Graph Stat. 2011;20:492–509. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman EA. The graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1568–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:567–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(4):1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlin BP, Louis TA. Bayesian Methods for Data Analysis. Baco Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelfand AE, Smith AFM. Sampling based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J Am Stat Assoc. 1990;85:398–409. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys. 1953;21:1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hastings WK. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov Chains and their applications. Biometrika. 1970;57:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lunn D, Spiegelhalter D, Thomas A, Best N. The bugs project: evolution, critique and future directions (with discussion). Stat Med. 2009;28:3049–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martyn P. Jags Version 3.3.0 Manual. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Lyon, France; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gelfand AE, Sahu SK, Carlin BP. Effecient parametrizations for normal linear mixed models. Biometrika. 1995;82:479–488. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelfand AE, Sahu SK, Carlin BP. Effecient parametrizations for generalized linear mixed models. Bayesian Stat. 1996;5:165–180. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilks WR, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter DJ. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice. London: Chapman & Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelman A, Rubin DB. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat Sci. 1992;7:457–472. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegelhalter DJ, Best N, Carlin BP, van der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit (with discussion). J R Stat Soc: Ser B. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gelman A, Meng X, Stern HS. Posterior predictive assessment of model fitness via realized discrepancies. Stat Sin. 1996;6:733–807. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Bayesianly justifiable and relevant frequency calculations for the applied statistician. Ann Stat. 1984;12:1151–1172. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiegelhalter DJ, Thomas A, Best N, Gilks WR. BUGS Examples 0.30. Cambridge: MRC Biostatistics Unit; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plummer M. JAGS: a Program for analysis of Bayesian graphical models using Gibbs sampling. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Distributed Statistical Computing (DSC 2003); March 20–22, 2003; Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stan Development Team. Stan Modeling Language User’s Guide and Reference Manual. 2015.

- 25.Betancourt MJ, Girolami M. Current Trends in Bayesian Methodology with Applications. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2015. 10.1201/b18502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leurgans S, Moyeed R, Silverman B. Canonical correlation analysis when the data are curves. J R Stat Soc: Ser B. 1993;55:725–740. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dubin J, HG M Dynamical correlation for multivariate longitudinal data. J Am Stat Assoc. 2005;100:872–881. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measuements. Lancet. 1986;327(8476):307–310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danaher MR, Roy A, Chen Z, Mumford SL, Schisterman EF. Minkowski-Weyl priors for models with parameter constraints: an analysis of the BioCycle study. J Am Stat Assoc. 2012;107(500):1395–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.