Abstract

Purpose:

To define the clinical characteristics of patients with variants in TCF20, we describe 27 patients, 26 of whom were identified via exome sequencing. We compare detailed clinical data with 17 previously reported patients.

Methods:

Patients were ascertained through molecular testing laboratories performing exome sequencing (and other testing) with orthogonal confirmation; collaborating referring clinicians provided detailed clinical information.

Results:

The cohort of 27 patients all had novel variants, and ranged in age from two to 68 years. All had developmental delay/intellectual disability. Autism spectrum disorders/autistic features were reported in 69%, attention disorders or hyperactivity in 67%, craniofacial features (no recognizable facial gestalt) in 67%, structural brain anomalies in 24%, and seizures in 12%. Additional features affecting various organ systems were described in 93%. In a majority of patients, we did not observe previously reported findings of postnatal overgrowth or craniosynostosis, in comparison to earlier reports.

Conclusion:

We provide valuable data regarding the prognosis and clinical manifestations of patients with variants in TCF20.

Keywords: Autism, Developmental delay, Exome, Intellectual disability, TCF20

(a). INTRODUCTION

Neurodevelopmental disorders are relatively common, estimated to affect approximately 1–3% of the population1. The causes are diverse, and include both genetic and non-genetic etiologies. Among the known genetic causes, pathogenic variants in thousands of genes have been implicated in syndromic and nonsyndromic monogenic forms of neurodevelopmental disorders; more complex causes are also areas of active investigation2.

Genomic approaches to diagnosis, including exome sequencing, which can identify both single nucleotide variants (SNVs) as well as certain structural variants (SVs), have emerged as powerful tools to help provide molecular diagnoses for affected patients with many types of genetic and suspected genetic conditions. Previous exome studies have described a diagnostic rate of up to 33% in cohorts of patients with neurodevelopmental disorders3–8. Importantly, these technologies can efficiently identify known as well as novel causes of disease. The latter are accumulating rapidly, with a recent rate of over 14 new disease genes published per month, 78% of which were identified by exome sequencing9.

Among the many causes of neurodevelopmental disorders, variants in TCF20 gene have been implicated in neurodevelopmental conditions with associated features. TCF20 encodes a transcriptional co-regulator10, initially identified by its ability to bind the stromelysin-1 PDGF-responsive element (SPRE), an element of the stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3/MMP3) promoter11. TCF20 (also termed AR1, SPBP, SPRE-binding protein) is localized to the nucleus. The nuclear factor TCF20 is highly expressed in brain12, especially in the hippocampus and cerebellum13, and probably acts as a coactivator of various structurally and functionally disparate transcription factors binding to target sequences in promoters or enhancers, such as c-Jun, Ets, Sp1 and Pax614,15. TCF20 is paralogous to RAI114, the causative gene in Potocki–Lupski syndrome (duplication of 17p11.2), which is associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in ~90% of cases16,17; and Smith–Magenis syndrome (deletion of 17p11.2), characterized by severe intellectual disability and neurobehavioural problems, including ASD18,19. A yeast two-hybrid screen with the ZNF2 domain of TCF20 as bait identified RAI-1 as a binding partner, showing that these proteins are able to interact and therefore may also be functionally related14. Functionally essential regions of the transcriptional co-regulator TCF20 include an N-terminal transactivation domain; three nuclear localization signals; and several C-terminal DNA- and chromatin-binding domains – including a zinc finger domain – as well as three PEST domains10,20. To date, at least 17 individuals with molecularly-identified disease causing variants in TCF20 have been described in peer-reviewed publications20–24. Both de novo and inherited variants, including SNVs and SVs, have been reported. Described clinical features in these patients have included mild-to-moderate intellectual disability with or without ASD and accompanying features such as proportionate overgrowth and muscular hypotonia20–23. However, no clearly-recognizable syndromic phenotype has been described, and robust clinical data has not been available for some patients.

To help provide more clinically-relevant information for clinicians and researchers and for the families of affected individuals, we describe 27 additional individuals from 24 families with variants in TCF20 that were unique to each family. Our observations include both neurologic and non-neurologic features that have not been previously documented.

(b). MATERIALS AND METHODS

Individuals identified with novel variants in TCF20 were enrolled in this study based on genotype results. All cases that GeneDx has reported with loss-of-function variants in TCF20, whether de novo, inherited, or of unknown inheritance, as well as de novo missense variants were offered participation in this study (n=23). Referring providers for 15 cases (Patients 1–5, 7–9, 10a-b, 13, 14, 18, 20, 24) opted to participate. Additional cases (Patients 6, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17a-c, 19, 21–23) were ascertained via GeneMatcher25. Patient 23 has been previously reported24, though without detailed phenotypic information and therefore we have included this patient as one of our cohort. Clinical information was obtained via provider completion of an open-ended questionnaire; therefore, we were unable to uniformly determine if every feature was assessed in each patient. This study was conducted under GeneDx’s research protocol “Research to Expand the Understanding of Genetic Variants: Clinical and Genetic Correlations”, approved by the Western IRB (protocol #20171030). All research subjects provided written consent to participate, either through GeneDx’s research protocol or as required by their clinical institution. Written informed consent was obtained for the use of photographs (where applicable). All probands, with the exception of Patient 16 who was diagnosed by a 450-gene sequencing panel, were diagnosed by exome-based platforms and all results were subsequently confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Family member analyses were completed as part of trio-based exome sequencing approach or via targeted sequencing. All testing was performed in a diagnostic setting with the exception of the initial exome sequencing for Family 17, which was performed in a research study.

(c). RESULTS

We describe 27 individuals from 24 families with novel variants in TCF20. Common features include developmental delay/intellectual disability (DD/ID) (100%), ASD or autistic features (69%), attention disorders or hyperactivity (67%), additional neurobehavioral concerns (85%), hypotonia (63%), other neurologic or muscular concerns (85%), and minor anomalies noted on physical examination (74%). Additional features affecting various organ systems were reported in 93% of patients (see Table 1 and Table S1 for details).

Table 1.

Summary of our cohort and previously published patients with variants in TCF20

| Our cohort (n=27) | Babbs et al., 2014 (n=4)a | Schäfgen et al., 2016 (n=2) | DDD, 2017 (n=7) | Lelieveld et al., 2016 (n=4) | Total (n=44) | Total % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurocognitive Features | |||||||

| DD/ID | 27/27 | 3/4 | 2/2 | 7/7 | 4/4 | 43/44 | 97 |

| ASD/autistic features | 18/26 | 4/4 | 1/2 | 2/7 | NR | 25/39 | 64 |

| Attention disorder/hyperactivity | 18/27 | NR | NR | 2/7 | NR | 20/34 | 59 |

| Other neurobehavioral diagnoses or concerns | 23/27 | NR | 2/2 | NR | 1/4 | 26/33 | 79 |

| Hypotonia | 17/27 | NR | 2/2 | NR | 1/4 | 20/33 | 61 |

| Seizures | 3/26 | NR | 1/2 | NR | 0/4 | 4/32 | 13 |

| Other neurologic presentations | 22/27 | NR | 1/2 | NR | NR | 23/29 | 79 |

| Normal brain MRI | 16/21 | NR | 2/2 | 0/2 | NR | 18/25 | 72 |

| Additional Features | |||||||

| Dysmorphic craniofacial features | 18/27 | NR | 0/2 | NR | 3/4 | 21/33 | 64 |

| Other minor malformations | 10/27 | NR | 2/2 | NR | 0/4 | 12/33 | 36 |

| Birth defect | 3/27 | NR | 0/2 | NR | NR | 3/29 | 10 |

| Gastrointestinal | 15/27 | NR | NR | NR | 1/4 | 16/31 | 52 |

| Skeletal | 14/27 | NR | 2/2 | NR | 0/4 | 16/33 | 48 |

| Ophthalmologic | 14/27 | NR | NR | 2/7 | 0/4 | 16/38 | 42 |

| Dermatologic | 7/27 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7/27 | 26 |

| Cardiovascular | 4/27 | NR | NR | NR | 0/4 | 4/27 | 15 |

| Genitourinary | 2/27 | NR | NR | NR | 0/4 | 2/31 | 6 |

| Immunologic | 2/27 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2/27 | 7 |

| Overgrowth | 2/24 | NR | 2/2 | NR | 0/4 | 4/26 | 15 |

| Macrocephaly | 2/22 | NR | 2/2 | 2/7 | 0 | 6/31 | 19 |

| Craniosynostosis | 0/27 | 2/4 | NR | NR | NR | 2/31 | 6 |

Patients with translocations disrupting TCF20 and de novo variants (Family 1, Individuals II-4 and II-2; Family 2; Family 6)

DDD, Deciphering Developmental Disorders. DD/ID, developmental delay/intellectual disability. ASD, autism spectrum disorder. NR, not reported.

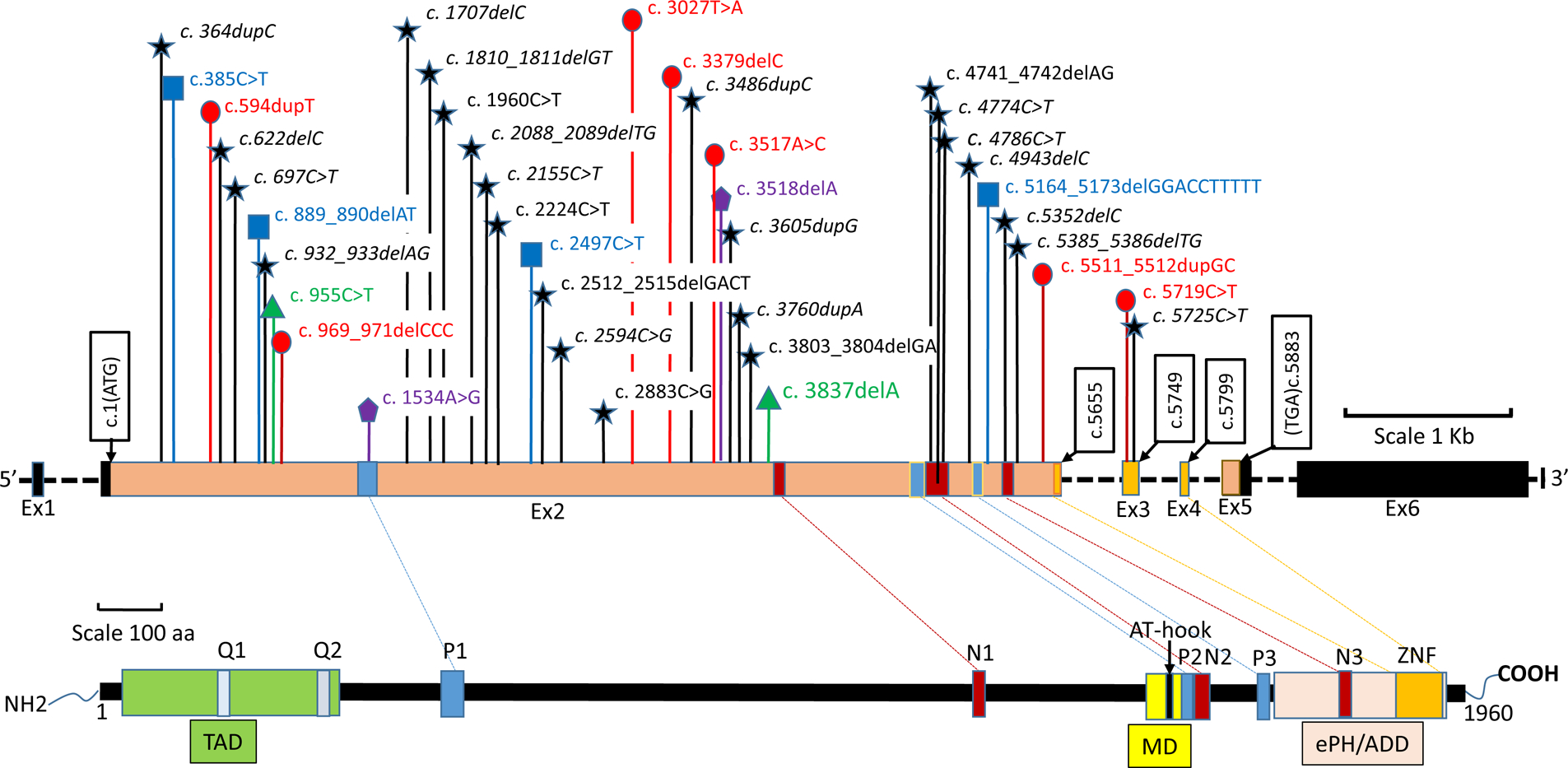

Our cohort includes 15 males and 12 females. Proband ages at the time of data collection ranged from two to 68 years (mean: 18 years, median: 10 years). Twenty-three novel frameshift and nonsense variants as well as one missense variant were observed, with no recurrent variants (Figure 1). None of the variants were present in large population cohorts26 or GeneDx internal data. The single de novo missense variant (p.H1909Y) is a non-conservative amino acid substitution that occurs at a position that is conserved across species and in silico analysis supports a deleterious effect. While most loss-of-function variants were either proven (n=17) or expected de novo based on family history, two cases were familial. In siblings 10a and 10b, the variant was not detected in the blood cells of the unaffected parents, likely due to germline mosaicism. In siblings 17a, 17b, and 17c, the variant was not identified in samples from the unaffected mother or unaffected brothers, but a DNA sample was not available from the deceased unaffected father.

Figure 1: TCF20 variants.

Upper panel: Genomic structure of the TCF20 gene. Exons are shown to scale with the coding sequence in color and untranslated regions in black. The position of the first coding nucleotide is shown in exon 2, and numbers in other black boxes indicate cDNA numbering of the last nucleotides of exon boundaries or last nucleotide of stop codons. Introns are depicted by black horizontal dashed line and sizes are not indicated. Novel variants are represented in black stars, and previously reported variants are represented in red circles23, blue squares21, green triangles22, and purple pentagons20. De novo novel variants are italicized. Lower panel: Diagram representing the TCF20 protein with previously annotated domains20. TAD, trans activation domain. Q1/Q2, glutamine-rich stretches. P1-P3, PEST domains. N1-N3, nuclear localisation signals. MD, minimal DNA binding domain. ZNF, zinc finger domain. ePHD/ADD, extended plant homeodomain/ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L.

Consistent with the current literature20–23, all individuals in our cohort have variable degrees of DD/ID. Reported full-scale IQ scores (n=7) range from the high-50s to normal with mean and median at 69. Developmental delay was reported in all patients, with an average age of sitting at 10 months (n=17), walking at 20 months (n=22), and talking at 23 months (n=19), similar to the milestones previously reported23. There were no speech concerns noted for 11 patients, but significant speech problems including apraxia or articulation difficulties were reported in eight patients. Most patients receive or have received developmental interventions and/or special education, and some teenagers and adults require assistance for self-care (n=18).

The presence of additional neurobehavorial issues was frequently described in this cohort. The majority of individuals are reported to have a diagnosis or concern for ASD (n=18/26; 69%) and/or attention disorders (n=18/27, 67%). Additional diagnoses or concerns affecting learning, behavior, and psychiatric health were reported in the majority of individuals (n=23/27, 85%); concerns reported in multiple individuals are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Neurobehavioral diagnoses and concerns reported in multiple patients.

| Diagnosis/Concern | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Attention disorder/hyperactivity | 18 |

| ASD/autistic features | 18 |

| Anxiety | 10 |

| Learning disabilities | 6 |

| Sensory integration/processing disorder | 5 |

| Fine motor issues | 4 |

| Depression | 4 |

| Obsessive/perseverating | 4 |

| Poor eye contact | 4 |

| Stereotypic behaviors | 4 |

| Aggression | 3 |

| Developmental coordination disorder/dyspraxia | 3 |

| Social delays | 3 |

| Tantrums/meltdowns | 3 |

ASD, autism spectrum disorder.

Other neurologic and related manifestations were also prevalent in the cohort. Hypotonia was reported in 17 individuals (63%). Hypertonia was reported in a minority (n=3) and was limited to the lower extremities in two of these three cases. At least one other neurologic concern was reported in 23/27 (85%) individuals, the most common of which was ataxia, gait disturbance, balance issues, or poor coordination (n=15). Additional neurologic manifestations reported in multiple individuals include tremor (n=6), muscular weakness (n=4), brisk reflexes (n=4), migraine headaches (n=3), fatigue (n=3), and concern for myopathy (n=2). Seizures were only diagnosed in three individuals, all of which were childhood-onset. Patient 5 was diagnosed with focal epilepsy at age 11 but has been seizure-free for a year and is currently being weaned off medication. Patient 8 had seizures while sleeping and is treated with medication. Since the age of five, Patient 24 has had multiple types of seizures and a diagnosis of refractory epilepsy/intractable generalized epilepsy.

Despite the frequency of neurologic symptoms, brain MRI was normal in most individuals who underwent brain imaging (n=16/21, 76%). Two individuals were noted to have thickening of the corpus callosum, and findings reported in single cases included mild prominence of the atria and occipital horns with mild pitting of adjacent white matter, subependymal neuronal heterotopias, and nonspecific gliosis in the left frontal lobe with mild white matter volume loss. As cerebellar hypoplasia is the only brain malformation that has been reported previously23, there do not appear to be consistent neuroimaging findings to date.

In regards to non-neurologic findings, craniofacial features were reported in 18/27 (67%) and other minor malformations in 10/27 (37%), but did not appear to constitute a single recognizable or distinct phenotype (Figure 2). Three patients were reported to have a congenital malformation, specifically pyloric stenosis (n=2) and hypospadias with chordee (n=1). Gastrointestinal (GI) problems were reported in 15 patients, the most common of which was constipation (n=9). Other GI abnormalities reported in a single patient include possible Crohn’s disease due to multiple polyps on colonoscopy, diverticular disease, gastroparesis, gastroesophageal reflux, inflammatory bowel disease, incontinence, and lactose intolerance. Skeletal problems were reported in 14 patients including scoliosis (n=4), pectus deformities (n=2), pes planus (n=9), and valgus deformities of the feet (n=3). Eye or vision problems were also reported in 14 patients, including strabismus (n=4), myopia (n=3), or kerataconus (n=3). Genitourinary problems were rare, with a single patient having chronic hematuria and crystals in the urine, and another with enuresis and recurrent urinary tract infections. Cardiovascular abnormalities were also infrequent, with mitral valve prolapse, branch bundle block and WPW syndrome reported in one patient each and borderline hypertension reported in only Family 10. Six individuals were reported to have eczema, keratosis pilaris, or ichthyosis, four of whom were also found to have at least one heterozygous pathogenic variant in FLG, which has been associated with these dermatologic findings. Both individuals with biallelic pathogenic variants in FLG were also reported to have asthma, as were two additional patients. Two individuals were reported to have immune problems, specifically autoimmune hepatitis and hyper IgE syndrome in one patient each.

Figure 2: Facial appearance of individuals with variants in TCF20.

While minor craniofacial anomalies are noted in the majority of patients, a specific gestalt has not emerged. A, Patient 2. B, Patient 11. C, Patient 21. D, Patients 17a-c.

The majority of patients (20/27) reported normal growth parameters. Two patients were reported to have macrocephaly. Four patients’ heights were at least two standard deviations above the mean (>+2 SD), but midparental heights were not provided. In two of these four patients, birth length was also >+2 SD. Also in two of these patients, weight was >+2 SD. Patient 21 had short stature (<−2SD) with obesity (>+2SD) of unknown etiology after endocrine workup and treatment with growth hormone therapy. An additional patient was noted to have weight >+2SD with normal height.

Seven of the patients were adults, ranging in age from 19 to 68 years. Health issues reported exclusively in the adults include the above-mentioned concerns for Crohn’s disease (n=1) and diverticular disease (n=1), cataracts (n=1), mitral valve prolapse and branch bundle block (n=1), and borderline hypertension (n=2, siblings). In addition, one adult in his 60s is being evaluated for possible cognitive decline. The adult brothers (Patients 17a, 17b, and 17c) live in supported accommodation and work in supported employment.

Lastly, five individuals harbored a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in at least one other gene that may be contributing to the patient’s phenotype (Tables S1 and S2). These included pathogenic variants in FLG (as discussed above), TNFRSF13B, and DNM2. Three individuals from two families also harbored variants in ACMG Secondary Findings genes (LDLR or BRCA2) that were not expected to be contributing to the patient’s phenotype27.

(d). DISCUSSION

This is the largest cohort of patients with variants in TCF20. Based on the data from our cohort and previously reported patients, several conclusions can be drawn. First, patients with TCF20-related disorders universally have DD/ID and exhibit high prevalence of features such as ASD, attention disorders (each reported in over half of patients), and other neurobehavioral diagnoses. Despite the prominent neurologic component, frank structural brain abnormalities and seizures were not frequently reported. Features affecting other organ systems, such as gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, skeletal, and craniofacial, were also described, though a specific gestalt was not evident.

Second, certain previously described features, such as proportionate postnatal overgrowth22 or craniosynostosis20, were not observed in our cohort. Our data supports TCF20-related disorders being a non-syndromic neurodevelopmental condition. Therefore it is possible that such features are rare or possibly coincidental features. As some of our patients had other reported variants in addition to those in TCF20, it is possible that some of the clinical features in the previously reported cohorts were modified by additional genetic variants.

Third, our cohort includes at least one family with germline mosaicism. To our knowledge, germline mosaicism has not yet been reported in association with TCF20-related disorders. The documentation of germline mosaicism is essential for recurrence risk counseling.

Lastly, we anticipate that molecular diagnosis of additional patients with TCF20-related disorders will continue via testing using panels or whole exome/genome platforms. The patients described in this cohort had a variety of clinical tests prior to exome testing; conducting exome testing may be considered in order to arrive at a diagnosis more efficiently and affordably. The ability to detect small, clinically relevant copy number variants via exome testing, as well as the higher yield of the latter versus microarray may also be taken into consideration when selecting genetic tests28. There is increasing evidence that, in many clinical situations in which a genetic etiology is suspected, broad testing provides a more efficient and cost-effective strategy than a more targeted approach29,30.

While more study is necessary, our findings support the frequency of neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioral manifestations in these patients, and early recognition of these issues may allow prompt diagnosis and management of these sequelae, which may benefit patients and families. Similarly, the frequency of gastrointestinal issues – at least some of may be related to the neurological findings – warrants awareness that these findings may arise and require interventions. Awareness of the possibility relatively infrequent but clinically important manifestations such as seizures may also be helpful. As with patients with other genetic conditions, who may have a variety of other organ systems affected, clinicians should be aware of other medical sequelae that may impact medical management. As more patients are diagnosed with TCF20-related disorders, phenotypic expansion may occur. In addition, genotype-phenotype correlations may become apparent. While to date all variants in TCF20 are unique, future studies may investigate the clinical and molecular impacts of variant type or position.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

E.T., A.C., G.D., J.J., K.G.M., R.E.P., R.W., B.D.S., and Z.Z. are employees of GeneDx, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of OPKO Health, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mefford HC, Batshaw ML, Hoffman EP. Genomics, intellectual disability, and autism. N Engl J Med 2012;366(8):733–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissers LE, Gilissen C, Veltman JA. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nat Rev Genet 2016;17(1):9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee H, Deignan JL, Dorrani N, et al. Clinical exome sequencing for genetic identification of rare Mendelian disorders. JAMA 2014;312(18):1880–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farwell KD, Shahmirzadi L, El-Khechen D, et al. Enhanced utility of family-centered diagnostic exome sequencing with inheritance model-based analysis: results from 500 unselected families with undiagnosed genetic conditions. Genet Med 2015;17(7):578–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald TW, Gerety SS, Jones WD, et al. Large-scale discovery of novel genetic causes of developmental disorders. Nature 2015;519(7542):223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright CF, Fitzgerald TW, Jones WD, et al. Genetic diagnosis of developmental disorders in the DDD study: a scalable analysis of genome-wide research data. Lancet 2015;385(9975):1305–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posey JE, Rosenfeld JA, James RA, et al. Molecular diagnostic experience of whole-exome sequencing in adult patients. Genet Med 2016;18(7):678–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, et al. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet Med 2016;18(7):696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon BD, Lee T, Nguyen AD, Wolfsberg TG. A 2.5-year snapshot of Mendelian discovery. Mol Genet Genomic Med 2016;4(4):392–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darvekar S, Johnsen SS, Eriksen AB, Johansen T, Sjøttem E. Identification of two independent nucleosome-binding domains in the transcriptional co-activator SPBP. Biochem J 2012;442:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz L, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. Molecular characterization of a novel transcription factor that controls stromelysin expression. Mol Cell Biol 1995;15:3164–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray PA, Fu H, Luo P, et al. Mouse brain organization revealed through direct genome-scale Tf expression analysis. Science 2004;306:2255–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, et al. : Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature 2007;445:168–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rekdal C, Sjottem E, Johansen T. The nuclear factor SPBP contains different functional domains and stimulates the activity of various transcriptional activators. J Biol Chem 2000;275(51):40288–40300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gburcik V, Bot N, Maggiolini M, Picard D. SPBP is a phosphoserine-specific repressor of estrogen receptor alpha. Mol Cell Biol 2005; 25(9):3421–3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walz K, Paylor R, Yan J, Bi W, Lupski JR. Rai1 duplication causes physical and behavioural phenotypes in a mouse model of dup(17)(p11.2p11.2). J Clin Invest 2006;116:3035–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potocki L, Bi W, Treadwell-Deering D, Carvalho CM, Eifert A, Friedman EM, Glaze D, Krull K, Lee JA, Lewis RA, Mendoza-Londono R, Robbins-Furman P, Shaw C, Shi X, Weissenberger G, Withers M, Yatsenko SA, Zackai EH, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Characterization of Potocki-Lupski syndrome (dup(17)(p11.2p11.2)) and delineation of a dosage-sensitive critical interval that can convey an autism phenotype. Am J Hum Genet 2007;80:633–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slager RE, Newton TL, Vlangos CN, Finucane B, Elsea SH. Mutations in RAI1 associated with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Nat Genet 2003;33:466–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laje G, Morse R, Richter W, Ball J, Pao M, Smith AC. Autism spectrum features in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2010;154C:456–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babbs C, Lloyd D, Pagnamenta AT, et al. De novo and rare inherited mutations implicate the transcriptional coregulatory TCF20/SPBP in autism spectrum disorder. J Med Genet 2014;51(11):737–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lelieveld SH, Reijnders MR, Pfundt R, et al. Meta-analysis of 2,104 trios provides support for 10 new genes for intellectual disability. Nat Neurosci 2016;19(9):1194–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schäfgen J, Cremer K, Becker J, et al. De novo nonsense and frameshift variants of TCF20 in individuals with intellectual disability and postnatal overgrowth. Eur J Hum Genet 2016;24(12):1739–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study. Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature 2017; 542(7642):433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling KM, Thompson ML, Amaral MD, et al. Genomic diagnosis for children with intellectual disability and/or developmental delay. Genome Med 2017;9(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, et al. GeneMatcher: A Matching Tool for Connecting Investigators with an Interest in the Same Gene. Hum Mutat 2015;36(10):928–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016; 536(7616):285–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalia SS, Adelman K, Bale SJ, et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2017;19(2):249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark MM, Stark Z, Farnaes L, et al. Meta-analysis of the diagnostic and clinical utility of genome and exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in children with suspected genetic diseases. NPJ Genom Med 2018;3:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monroe GR, Frederix GW, Savelberg SMC, et al. Effectiveness of whole-exome sequencing and costs of the traditional diagnostic trajectory in children with intellectual disability. Genet Med 2016;18(9):949–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan YT, Dillon OJ, Stark Z, et al. Diagnostic Impact and Cost-effectiveness of Whole-Exome Sequencing for Ambulant Children with Suspected Monogenic Conditions. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(9):855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.