By Max Bingham, PhD

Medicaid Expansion Has Resulted in Improvements in Diabetes Outcomes in the U.S.

The expansion of Medicaid health insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act in the U.S. has led to improvements in diabetes management and health outcomes in individuals with diabetes, according to Lee et al. (p. 1094). In particular, in states where diabetes rates are considered higher—the “diabetes belt”—there were substantial improvements in care and health outcomes in patients with diabetes. The findings, the authors suggest, will likely have implications for policy, not least because they also show that in states where expansion did not occur, care and health outcomes did not improve over the same implementation period. The study looked at self-reported outcomes of thousands of individuals with diabetes included in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Using a quasi-experimental approach, they looked at scores for self-reported measures of access to health care, diabetes management, and health status in states where there was or was not Medicaid expansion. In particular, they compared scores before and after expansion and also compared outcomes between states with higher and lower rates of diabetes. The study covers the period 2011–2016 and therefore the implementation of Medicaid expansion that started in 2014. The authors found that, after adjusting for a series of factors, Medicaid expansion did result in statistically significant improvements in the scoring for access to care (estimated score change 0.09, P = 0.023), diabetes management (1.91, P = 0.001), and health status (0.10, P = 0.026). In contrast, in states that did not expand Medicaid coverage, scores remained flat. Commenting more widely, author Jusung Lee told us: “Our study reveals the positive effects of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act on diabetes management. The findings also point out the salience of emerging health disparities and challenges in diabetes care among non–Medicaid expansion states with high diabetes rates. We believe our study will have important implications for policy makers and the diabetes care community in their efforts to control diabetes.”

States with (dark gray) and without (light gray) Medicaid expansion included in the study. States in white were not included in the study. Asterisks indicates states with high diabetes rates.

Lee et al. The impact of Medicaid expansion on diabetes management. Diabetes Care 2020;43:1094–1101

Weight Loss With Liraglutide in Individuals With Increased Weight and Type 2 Diabetes Treated With Insulin

Liraglutide treatment for 56 weeks resulted in greater weight loss compared with placebo in individuals with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin who were also overweight or obese, according to Garvey et al. (p. 1085). Specifically, the extra weight loss was achieved on top of both groups receiving intensive lifestyle interventions. In addition, they also found evidence for improved glycemic control with liraglutide despite lower insulin doses at the end of the intervention. The observations come from the SCALE Insulin trial, which was a 56-week, randomized controlled trial designed to prospectively investigate the effects of liraglutide 3.0 mg versus placebo as an adjunct to intensive lifestyle intervention. Approximately 200 individuals were randomized to each group with coprimary outcomes of weight change and HbA1c change over the intervention period. A series of secondary outcomes were also included. The authors found that after 56 weeks of intervention, weight loss with liraglutide was 5.8%, while placebo resulted in a drop of 1.5%. The estimated treatment difference was –4.3%, which did reach statistical significance (P < 0.0001). Just over half of individuals in the liraglutide group managed a clinically significant weight loss of ≥5%, while only a quarter reached the same target in the placebo group. Greater reductions in HbA1c and daytime glucose levels were also seen with liraglutide as well as a reduced need for insulin compared with placebo. In terms of safety, the authors report higher rates of hypoglycemia with placebo but conversely more incidents of gastrointestinal issues with liraglutide. However, they report that overall no new safety signals were detected and the overall safety profile of liraglutide in the trial was in line with previous studies. Based on the findings, they conclude that liraglutide treatment on top of intensive lifestyle intervention was superior to placebo in terms of weight loss, improved glycemic control despite lower requirements for insulin, and reduced rates of hypoglycemia in the population they studied.

Hyperglycemia Crisis Events Increased in the U.S. in the Period 2009–2015

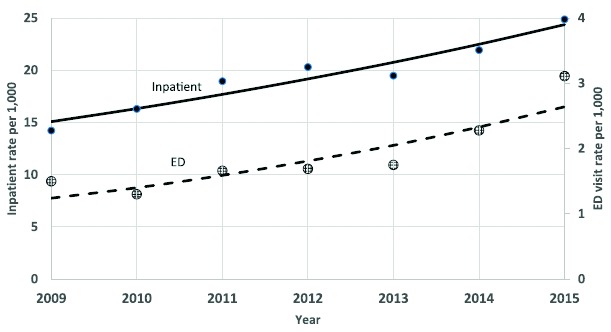

Rates of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS) increased in the U.S. in the period 2009–2015, according to Benoit et al. (p. 1057). Specifically, this increase occurred in both emergency department and inpatient settings and included adults of both sexes in all age-groups in all regions of the country. The conclusions come from an analysis of data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample and the National Inpatient Sample that covered the period 2006 through the end of September 2015. The authors found that from 2009 onward event rates for DKA increased at an annual percentage change of 13.5% for emergency department visits, while inpatient admissions increased by 8.3%. For HHS, there was a similar trend with emergency department visits increasing by 16.5% and inpatient admissions increasing by 6.3%. Over time, the majority of DKA events were in younger adults and in adults with type 1 diabetes. Meanwhile, HHS events occurred more frequently in middle-aged adults and in adults with type 2 diabetes. In terms of possible explanatory factors, they point toward higher rates of hyperglycemic events in lower-income individuals with public health insurance and also geographical variations. However, they stress that further studies will be needed to definitively uncover what might have caused the increases. They do discuss some possible reasons, including rates of infectious and noninfectious disease, drug abuse, side effects of prescription diabetes drugs, and the increasing price of insulin over the same period. Commenting further, author Stephen Benoit told us: “To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive report to assess U.S. national trends of diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state in both emergency department and inpatient settings. Although these data do not provide an etiology of the increased rates of hyperglycemic crisis, we have identified some subpopulations at higher risk. More detailed data with clinical, economic, and community characteristics may help determine specific factors leading to these trends, which could help identify preventive strategies.”

Age-adjusted DKA emergency department (ED) and inpatient hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults with diagnosed diabetes, 2009–2015.

Dietary Saturated Fat Compared to Free Sugars for Liver, Metabolic Risks

The effects of changing the relative proportion of total energy intake provided by dietary fat or dietary sugar are described by Parry et al. (p. 1134). They suggest that increased saturated fat intake might increase intrahepatic triacylglycerol, an indicator of steatosis, and also increase postprandial plasma glucose and insulin compared with a diet enriched in free sugars. Based on the findings, they label a diet enriched in saturated fat as “more harmful to metabolic health than a diet enriched in free sugars.” The findings come from a randomized crossover study of 16 overweight men without diabetes who consumed diets enriched in either saturated fat or free sugars for 4 weeks and then after a washout period swapped onto the corresponding alternate diet. Various imaging and tracer techniques were used to determine outcomes. The authors found that the diet enriched in saturated fat resulted in a 39% increase in intrahepatic triacylglycerol, while the diet enriched in sugar resulted in no increase. They also found no difference in levels of fasting plasma glucose or insulin concentrations following the diets. However, using a mixed meal test after the dietary periods, they found that the diet with increased saturated fat content resulted in higher and more prolonged peaks in postprandial glucose and insulin levels than those seen with the diet enriched in sugar. They also note that there were significant decreases in various measures of cholesterol (including HDL cholesterol) with the diet enriched in sugar. In terms of limitations, participants did experience a greater increase in caloric intake during the high-fat diet (∼476 calories) compared to the diet with increased sugar (∼108 calories). This means it is (still) unclear whether the increase in intrahepatic triacylglycerol seen with the diet with added saturated fat was due specifically to the added fat or the general increase in calories.