Abstract

Background

Like other epidemics, the current heroin epidemic in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic is a largely invisible and devastating social problem linked to numerous structural and social determinants of health.

Methods

In this article, we connect a community-based participatory research methodology – “PhotoVoice” – with the theoretical orientation of critical medical anthropology to identify local interpretations of complex social and structural factors that are most salient to the well-being of local Dominican populations affected by drug addiction.

Results

Specifically, we describe Proyecto Lentes (Lens Project), a PhotoVoice initiative launched in 2014, which brought together active drug users to visually unveil and critically analyze the micro- and macro-factors shaping the marginalized and stigmatized drug addiction epidemic in Santo Domingo.

Conclusions

While the synthesis of PhotoVoice and critical medical anthropology provides a powerful political analysis tool, this fusion is particularly apt in its ability to capture the “invisible voices” of marginalized communities, potentially contributing to future policy reform and social empowerment.

Keywords: PhotoVoice, critical medical anthropology, injecting drug users, drug policy reform, Dominican Republic

Introduction

Participatory photographic methods have been used in the social sciences and public health sciences to assess the social context of various health concerns (Bourgois, 2009; Graham et al., 2013; Harley, 2015; Helm et al., 2015; Mmari et al., 2014). PhotoVoice, a participatory photography methodology (Wang, 1999; Wang & Burris, 1997), aims to combine critical reflection on social conditions with photographic images that are analyzed and captioned collectively through a series of workshops. PhotoVoice methodology is intended to facilitate collective awareness of broader social, political, cultural, and interpersonal factors that shape everyday experience (Wang, 1999).

The critical and structural orientation of PhotoVoice – consistent with Freirian and other approaches to community pedagogy and “praxis” that inform such approaches (Freire, 1993) – is resonant with the conceptual orientation of “critical medical anthropology” (CMA), a theoretical and activist-driven anthropological approach drawing upon critical theory and ethnography to reframe health issues as fundamentally problems of social inequality and marginalization (Singer, 1995). This ontological orientation of CMA requires holistic approaches to public health and community activism, emphasizing change in the structures of institutional, legal, political-economic and social systems that are viewed as the primary drivers of health inequalities. This perspective has been used to understand the problematic clinical and social consequences of drug addiction (Bourgois, 1998; Rhodes, Singer, Bourgois, Friedman, & Strathdee, 2005). Due to the affinities of PhotoVoice as a participatory methodology and the theoretical orientation of CMA, our research was inspired by the synthesis of these approaches in addressing the growing heroin epidemic in the Dominican Republic – a Caribbean nation generally considered to have a relatively minor heroin epidemic, but which recent evidence suggests may be growing at an alarming rate (Day, 2012; OEA, CICAD, & CND, 2013).

As we aim to show through our team’s gallery of photographs produced by seven community collaborators and activist-artists, not only is heroin a growing, largely invisible and devastating social problem, but it can also be linked to numerous structural and social factors that community members poignantly documented in their daily lives. There are three primary goals of our analysis. First, we hope to demonstrate how a CMA approach to community ethnography can work in conjunction with PhotoVoice to identify and translate into local vernaculars the complex social and structural factors most salient to the health and rights of local populations affected by drug addiction. The ethnographic methods of participant observation and anthropology’s experience-near approach to fieldwork are particularly ripe for incorporating PhotoVoice, with important synergies that benefit each approach. Second, we illustrate how PhotoVoice can be adapted to active drug using populations for whom daily survival is a struggle, complicating the commitment of time and energy that comes with the development of a long-term photographic exhibit. For the men and women on our team who were struggling with addiction, there were also challenges related to withdrawal symptoms, confliict, violence, other health conditions, and the ethics of taking pictures in drug use areas. Thus, we summarize the lessons learned in successfully adapting PhotoVoice to active street-based drug users in Santo Domingo. Finally, we briefly illustrate the critical structural analyses of the “causes” of community suffering and ill-health by considering several photographs from the gallery and the ways these reframe individual health as the product of social, political, or economic ills. This is a useful application of theories of “social ills” – the notion that patterns of illness in societies are often rooted in social inequalities and power hierarchies – as described by medical anthropologists conducting ethnographic analyses similar to our own (e.g. Biehl, 2013). At the end of this paper, we return to this point to describe intersections between these theoretical considerations and discussions in visual culture regarding the impact of visual representations and their potential to both express and transform relations of power and inequality (Rose, 2012).

Background on Proyecto Lentes (Lens Project)

Proyecto Lentes was launched in 2014 and continues in its exhibition phase at the time of this writing; it began as a supplement to a larger ethnographic study of the social and structural context of HIV and drug abuse in the Dominican Republic, called the Syndemics Project. Through this larger study, the research team was engaged in an institutional ethnography of HIV/AIDS and drug service organizations in the Dominican Republic. The team’s ethnographers (the first four authors of this paper) came upon and began observing community volunteers at a local non-governmental organization, Fundación Dominicana de Reducción de Daños (Dominican Foundation for Harm Reduction), or FUNDOREDA, which was conducting harm reduction activities for drug users in Capotillo, a lower class barrio in Santo Domingo known to have a thriving street-based drug economy and violent clashes with the police. Harm reduction approaches to injecting drug use involve programs and services such as needle exchanges (programs that facilitate the exchange of a used needle for a free clean needle), education about cleaning injection equipment to prevent blood-borne infections such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C, and the use of opiate replacement therapies (ORT), like methadone or suboxone, to assist addicts in tapering safely off opiates.

Seven of the volunteers at FUNDOREDA – all current or former drug users – requested support from our team to document their experiences and struggles with addiction, and to tell their stories in a way that might positively impact public dialog on the severe problems with current drug policies. With financial support from the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center at Florida International University (FIU, Miami, Florida, USA), PhotoVoice workshops were held with seven street-based drug users from summer, 2014 through fall, 2015.

Two factors are critically important for understanding the social context in which we implemented Proyecto Lentes. First, under the current Dominican drug law (Law 50–88), which focuses primarily on the harsh criminalization of drug use, clinical treatments like methadone for ORT are defined as illegal drugs equivalent to heroin or cocaine (Agozino, 2014). Law 50–88 was modeled on zero-tolerance approaches promulgated by the United States under Ronald Reagan’s Presidency (Brotherton & Barrios, 2011), and represents the cornerstone of the DR’s response to illicit substance use. According to Article 7 of the law, anyone found in possession of small amounts of illegal drugs may be classified as a “narcotraficante” (narco-trafficker), and may be sentenced to years of incarceration. Relatedly, drug treatment programs are severely under-funded in the country, rarely incorporate evidence-based approaches to drug prevention and treatment and have been criticized by international human rights organizations for violating the rights of residents in treatment (Upegui-Hernández & Torruella, 2015).

Second, drug users face intense social stigmatization in the Dominican Republic, and are generally viewed as “damaged” persons who have given into bad habits or “vices” that are often seen as imported from abroad. The latter stereotype is further entrenched by the rapid growth in the deportation of Dominicans from the United States, most often resulting from drug convictions (Brotherton & Barrios, 2011). The combination of stigmatization and intense criminalization contributes to the high rates of arrest among drug users and their frequent abuse by the police, who have been known to plant drugs on residents of poor neighborhoods like Capotillo. Dominican scholars have emphasized Capotillo’s unique history of clashes with the police, due in part to settlement by members of international drug cartels in this neighborhood, which has increased drug-related violence and extrajudicial killings (Bobea, 2012). Dominican sociologist Lilian Bobea summarizes the situation of violence in Capotillo as follows:

Capotillo ranks among the barrios with the highest rates of victimization and homicide in the National District, which include Santo Domingo (a terrifying 64 deaths per 100,000 for the zone that includes the barrio). Those who die are mostly poor young males, gunned down either by rival gangs or by the police. (Bobea, 2012, p. 56)

Male deportees we interviewed for the larger study often reported engaging in the sale of drugs due in part to their intense stigmatization for their deportee status, resulting in virtual exclusion from formal labor (Padilla, Colon-Burgos, Varas-Diaz, Matiz-Reyes, & Parker, in press). Indeed, several of the activist-artists who participated in Proyecto Lentes were deportees, and had experienced extreme stigmatization and abuse by the public and the police.

Participants, methods, and procedures

The seven activist-artists we originally recruited in 2014 were living on the street or in “shooting galleries” – abandoned houses where heroin or crack is obtained and consumed. Including four men and three women, the participants were volunteers at FUNDOREDA and beneficiaries of the services provided there, including needle exchange, donations of clean injection kits, food aid, HIV testing and psychological counseling. Based on our additional ethnographic research on drug users in the broader metropolitan area of Santo Domingo, we believe that these participants were relatively typical of street-based heroin users in lower class barrios such as Capotillo. Their status as existing clients of this non-governmental organization assisted us in maintaining contacts with these individuals over the course of the project. These seven activist-artists participated in PhotoVoice workshops at FUNDOREDA’s offices led by Dr. Matiz-Reyes – a researcher on our FIU-based team with many years of experience working with vulnerable populations in the Dominican Republic and a skilled community facilitator who had conducted a prior PhotoVoice project in Detroit, Michigan, USA (Graham et al., 2013).

Through 12 months of regular meetings and participatory co-learning discussions, activist-artists met with our team to learn about photographic techniques, ethical procedures, captioning, policy mapping, the selection of images to create a story, and the logistics of developing an exhibit. Approximately 800 pictures were taken of a wide range of scenarios, following analytic, ethical, policy and artistic criteria that the group thoroughly discussed. Importantly, the group decided to select images and create interpretations for them collectively, prioritizing the group’s mission of social and policy change over the original intentions of the individual photographer. While the artist’s intentions were thoroughly discussed in collective discussions, selection of images for the final exhibition and captioning was done collectively and based on a process of consensus-building. For this reason, our analysis in this paper highlights the collective decisions of the larger group, rather than the motives or intentions of individual artists.

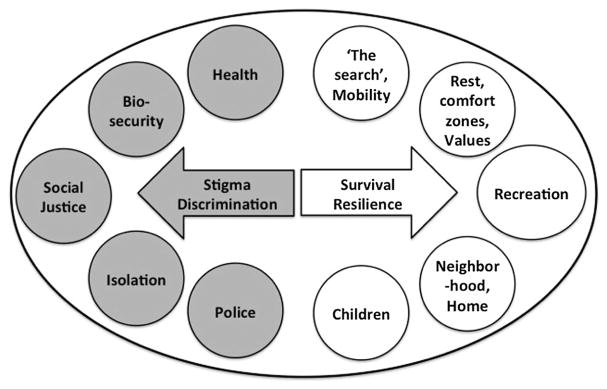

For example, because Law 50–88, the highly punitive Dominican drug law, was determined through initial discussions to be a priority for critical commentary, the selection of images involved discussion of the best visual representations and potential captions to build an effective critique of this law. Ultimately, the consensus-building process led to the selection of forty (40) images for the exhibit, and captions were refined through detailed discussions of each. Captions for each picture were intended to guide the viewer through specific framings of a community problem or challenge. In addition, the group decided to include “alternatives” to each problem within the captions; by alternatives, they intended to highlight the assets, resources or resilience with which people might confront each challenge. Finally, as summarized in Figure 1, the team developed a conceptual organization of 10 themes they wished to represent through the exhibit, which again were divided into two contrasting processes: Stigma /Discrimination and Survival /Resilience.

Figure 1.

Thematic organization of photographs, Proyecto Lentes.

The Proyecto Lentes unfolded in the context of a larger ethnography of Dominicans who are vulnerable to HIV/AIDS and problematic drug use. The ethnographic project was informed by syndemic theory, focusing on the structural and social determinants of the syndemic of HIV and drug use. While this article’s primary goal is not to present ethnographic data from our study, we will draw upon ethnographic findings in our analysis in subsequent sections when they foster a broader context for understanding the images and the captions produced by the activist-artists. One of the primary goals of our study was to describe the political and institutional structure of drug policies and programs in the Dominican Republic. To achieve this, we conducted key informant interviews and participant observation at 15 public and private substance use service organizations in Santo Domingo and Boca Chica (the two cities upon which our study focuses). We visited and observed approximately 45% (15 of 33) of the drug service organizations in this area, as listed in an official registry of such organizations provided to our team by the Dominican Consejo Nacional de Control de Drogas (National Council on Drug Control). After each visit, investigators took detailed ethnographic notes. All participants in the key informant interviews (N = 64) were mid-to-high-level representatives of these organizations – such as directors, program managers or program outreach staff – or other persons associated with the organization that provided our team a perspective on its institutional culture or functioning. These individuals also were experts in the overall structure of drug laws and policies and the ways these policies affect drug users. Below, we draw upon their insights in our interpretations of the PhotoVoice images and captions.

Next, we describe our adaptation of the PhotoVoice methodology to the daily realities and struggles for survival of people who are addicted to drugs in Santo Domingo.

Adaptation of PhotoVoice to ethnographic research on heroin use

PhotoVoice is a community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodology focused on empowerment and stakeholder engagement through visual representation. Feminist and critical theories underpin the process and empower community participants to think critically about their own communities. In one of the methodology’s seminal articles, Wang and Burris (1997) described the three main goals of the process as “(1) to enable people to record and reflect their community’s strengths and concerns, (2) to promote critical dialog and knowledge about important community issues through large and small group discussion of photographs and (3) to reach policymakers” (p. 370). PhotoVoice is beneficial to ethnographic research because it allows people to express their daily life-worlds in a language that is beyond the purely verbal, and to think critically about their worlds in the process of uncovering their hidden or implicit patterns and logics. The main approach to PhotoVoice facilitation involves a series of thought questions that foster reflection on the structures shaping specific scenarios or challenges. This process is also consistent with the theoretical orientation of CMA, emphasizing ethnographic analysis of broader social conditions of health. PhotoVoice also facilitates access to social settings that might be considered “hard-to-reach” or potentially dangerous to observe ethnographically, using the camera as a lens onto realities typically beyond the view of the researcher (e.g. private moments of drug injection).

PhotoVoice methodology has been used in a few studies aimed at observing, describing and analyzing drug using contexts or communities (e.g. Harley, 2015; Helm et al., 2015; Mmari et al., 2014). However, few PhotoVoice projects have centered on active adult drug users (Cordova et al., 2015; Pindera, 2003). Ours is a unique example of the adaptation of PhotoVoice methodology to situations of active injecting drug use under circumstances of systematic state abuse, intense social stigmatization and the virtual absence of effective drug programs. The extremely precarious conditions faced by the Proyecto Lentes team were therefore ironically both the object of analysis for the project and the principle barriers to its successful implementation. The seven activist-artists who originally committed to the project in 2014 often faced life-endangering health conditions such as overdose, hepatitis C infection, injection-site abscesses, chronic stress, physical and sexual violence (sometimes perpetrated by the police), and chronic diseases. Two of the original seven artists died of overdose during the first year of the project – an outcome that was virtually guaranteed by their inability to access clinical services due to discrimination of drug users in most medical facilities and the lack of services aimed at serving people with drug abuse problems. This resulted in the need to mourn the loss of our team members as well as to cope with inevitable delays in project implementation while we recruited and trained two additional participants. Ultimately, nine artist-activists contributed to the project.

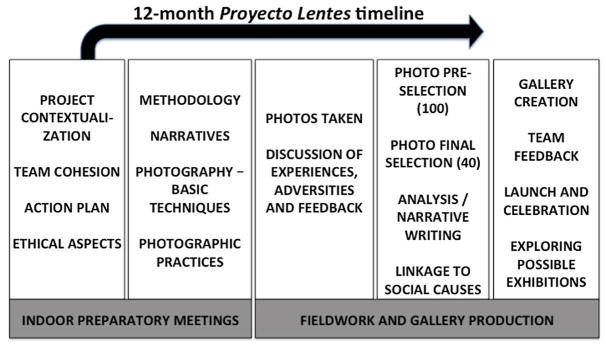

To create the PhotoVoice exhibit, formal meetings were held over the course of 12 months, following a sequence of steps that began with workshops and discussions indoors in preparation for the fieldwork, followed by photographic outings, analysis and gallery production. Figure 2 summarizes this process of training. Each step involved a minimum of two workshops, although at certain steps more meetings were required to thoroughly cover the topic, or to update individuals who had missed a session. Each meeting involved approximately two hours of discussion, during which the team shared a snack or a meal. It should be noted that between formal workshops, our investigative team maintained continual contact with the activist-artists through regular visits to the neighborhood, FUNDOREDA, and individual homes.

Figure 2.

Training phases of Proyecto Lentes.

During the workshops, it was common for team members to arrive under the influence, to report traumatic events that overwhelmed their capacity to participate, or to be too desperate to obtain their daily “curita” (literally cure or band-aid) – the term used by many heroin addicts to describe the first daily hit of heroin that temporarily staves off the pain of withdrawal symptoms. These conditions resulted in challenges in focusing the team and several open conflicts among participants that disrupted some training sessions. Further, sheer poverty and a street-based existence severely compromised their overall health, nutrition, and ability to meet basic needs.

To adapt the PhotoVoice methodology to these challenging circumstances, our team took several steps. First, and perhaps most importantly, we strove to encourage the conceptualization of the team as a family, referring to the group as “la familia FotoVoz” (the PhotoVoice family) to promote team cohesion and create a personal context for communication and conflict resolution. This was significant for the participants because many of them were estranged from their own families or forcibly separated from them due to their deportation, making the PhotoVoice family a critical resource for social support. The family environment also reduced feelings that the project was a job and, instead, helped participants become more emotionally involved through sharing their own feelings and holding each other accountable. The family mindset was developed through constant interaction, including frequent dinners at the meeting site and surrounding area restaurants. Moreover, Proyecto Lentes participants met bi-weekly to discuss their photos and community endeavors, leading to a context of consistency and trust.

Second, we established a donation-based food and clothing bank for street-based drug users that operated out of FUNDOREDA, allowing us to provide for some basic needs, involving family-style meals before or after each meeting. This helped address immediate concerns rather than expecting individuals to commit exclusively to the longer term goals of policy change. Third, we encouraged each member to watch over the others, to remind them of our meetings and to support one another in arriving to our meeting location. Fourth, as the project evolved and the photographic gallery was traveling to various exhibition locations, we incorporated professionalization opportunities by arranging events in which the artists could speak publicly, such as those we held at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo – the largest public university in the Dominican Republic and an institutional partner for our NIDA-funded project – or at public health conferences. This allowed participants to be validated for their work in venues where they would typically be excluded.

Finally, the anthropological approach of the larger project allowed us to be particularly responsive to local conditions and realities, and to use our ethnography to inform PhotoVoice. This group of community activists became both a source of ethnographic “data” on community experiences with drug addiction as well as a means to contribute directly to grassroots community organizing aimed at improving the policy environment for persons struggling with drug addiction. Since our institutional ethnography was intended to identify how policies, laws and institutions affect people who are addicted to drugs, the collaboration with the PhotoVoice family was an ideal opportunity to witness a grassroots effort by street-based drug users to express their voices in a public forum.

Analysis of photographs

In this section, we present six of the forty (40) images selected by the Proyecto Lentes team to represent the themes and messages determined as central to the social analysis accompanying PhotoVoice (see Figure 1). Here, our focus is on how the images and captions illustrate the themes of interest to the activist-artists, as well as the ways that they link individual experiences to the larger social conditions that frame them. For brevity, we include only the English translations of the Spanish captions written by the artists, but titles are given in both languages.

Images of the effects of medical abandonment

In representing their struggles with addiction, the artists chose several images that coalesced around the bodily wounds and scars that embody the effects of the broad social conditions that drug users face, in particular, the abandonment of these individuals by the medical establishment and the state. In Figure 3, entitled “Mi vida sobre el espejo” (My life on the mirror), the abscesses and wounds resulting from injection using unsanitary equipment (e.g. re-used needles or “cookers”) are linked metaphorically to what we might call “social pathologies” – the deficiencies and injustices that diminish the life chances of heroin addicts by denying them the clinical services that might mitigate the worst manifestations of addiction and its resulting physical damage. Here, the mirror serves multiple functions, representing the centrality of drugs – often cut or prepared on a small mirror such as the one shown balanced precariously on the man’s knee – to the life of the addict, but also the reflection (and reflexivity) of the photographer, who then invites us to examine the deficiencies in health services that are the fundamental causes of these prominent, festering wounds. The tiny pellet of heroin shown on the mirror is glossed as “my life,” highlighting the ways in which the incessant search for the substance overwhelms the addict’s daily life, becoming the predominant concern. The difficult-to-look-at quality of this photograph combined with the critical caption re-directs our disgust toward the larger context of a generalized lack of health services designed for persons suffering from addiction. Taken in this context, then, the wounds are social as much as they are physical.

Figure 3.

Mi vida sobre el espejo/My life on the mirror.

Analysis: Drug consumption is the main priority for some people, simply because it relieves the pain, overcomes the lack of health services and makes you forget the lack of opportunities. Alternatives: Specialized health services for people who have their lives in the hands of inopportunity and drugs.

Our ethnographic research documented many stories of the systematic denial of access to clinical services to persons suffering from drug addiction. Hospitals and clinics in the Dominican Republic are notorious for refusing treatment to drug users or those presumed to be addicts, including calling the police to encourage arrest when patients present with drug-related symptoms or overdose. Thus, individuals with abscesses like those shown in Figure 3 are also displaying stigmatizing signs of addiction, marks that further marginalize these individuals and make them more likely to be identified and targeted for violence or arrest. By proposing “specialized health services” for drug-addicted individuals, the activist-artists are therefore underlining the need to develop tailored clinical services designed for this abandoned community.

Figure 4 shows a similar reframing of injection, entitled “Grima” (Terror), which makes explicit connections between the injection equipment shown in the photograph and the policies and legal frameworks that criminalize users rather than support their survival and access to effective services. The call to “support the modification of Law 50–88” refers to ongoing debates in the DR regarding the reform of this highly punitive law, and to the need to enact harm reduction strategies that treat individuals as suffering from an illness rather than being criminals or expendable. During our institutional ethnography, we heard repeated stories of the hyper-criminalization of drug users resulting in repeated cycles of incarceration, and of the arrest of drug users who would present at hospitals in need of medical care. One individual told us a detailed story of being handcuffed to a gurney at a local clinic when the nurse identified him as a drug user, resulting in the individual being arrested even though he was not in the possession of drugs and was merely seeking care. Most of the key informants with whom we spoke recognized the importance of reforming the law in order to more fully support the public health needs and the rights of drug users. This image thus draws links between the daily practices of injection and the policies and legal protections that would support their health and well-being through harm reduction initiatives.

Figure 4.

Grima/Terror.

Analysis: Perfect team for the destruction of life. Pleasure and false calm, without norms or restrictions on the preparation of substances. Alternatives: Prevent this ghost for future generations. Reinforce harm reduction strategies for users. Support the modification of Law 50–88 for the protection of persons with addictions.

Images that humanize the suffering addict

One of the activist-artists who participated in the first phase of Proyecto Lentes but who tragically passed away from overdose in 2015, produced a photo that illustrates another theme of the exhibition: the humanity of the heroin addict, presented as a challenge to stereotypes of drug users. In Figure 5,“La ternura de Jesus” (The tenderness of Jesus), a picture of the photographer’s bed in a hidden corner of the shooting gallery where he slept is deeply moving in its juxtaposition of the filthy mattress with a clean, white teddy bear that defies the viewer’s attempt to relegate this place to oblivion and inhumanity. The use of the phrase “comfort zone” in referring to this scene further challenges the viewer’s potential responses that might be based on stigmatizing attitudes about addicts, and opens the possibility of reading this place as a sanctuary.

Figure 5.

La ternura de Jesús/The tenderness of Jesus.

Analysis: Amidst poverty feelings remain. There is a parallel world that we don’t know, a comfort zone where tenderness lives. Alternatives: Support programs with neighborhood groups, the church, and the state with more effective community services. Make this reality known for those who are unaware.

Similarly, Figure 6, “Dignidad que se mantiene” (Dignity remains), intentionally creates a rupture between the emotional valence that the image of a homeless addict might invoke in a viewer unfamiliar with such scenes, on the one hand, and the dignified attention to cleanliness and self-protection that the artist sees in this individual. The phrase “poverty is not only economic” reinforces this interpretation, suggesting that while this individual is poor, he is not without certain resources or a desire to live a humane and respectable existence. In the context of the highly stigmatizing attitudes that tend to circulate around drug users in the Dominican Republic, such messages are a direct challenge – an appeal to the viewer to look more carefully – and underscore the resilience of these individuals despite their conditions of homelessness and addiction.

Figure 6.

Dignidad que se mantiene/Dignity remains.

Analysis: Those who don’t fit within social constructions are seen as bad people. The pillow, quilt and sheet show there is a bit of dignity and that hope remains. Alternatives: Early interventions beginning in school to talk about addictions. Fight poverty that exists and understand that poverty is not only economic.

Interestingly, both images construct notions of safe space and “home” that force us to consider critically the nature of “homelessness”; as ethnographic research on homeless populations have demonstrated, the very idea of these individuals as being detached from or expelled from “home” reinforces their isolation and abandonment. The artists’ depictions re-appropriate this notion of home, making space for their symbolic reincorporation into humanity, and thereby provoking critical reflection by the viewer regarding society’s collective responsibility for these invisible beings.

Images challenging police abuse and corruption

Several of the photographs chosen by the team for the exhibition included references to the victimization of drug users by the police and the authorities, which is one of the primary reasons that heroin use is hidden from public view and occurs in areas that do not support the effective use of harm reduction techniques. As shown by other ethnographic research on injecting drug users (Bourgois, 2009), the criminalization of drug use and the constant threat of arrest or mistreatment by the police are the primary reasons that street-based drug users often remain hidden within plain sight – injecting under a bridge, for example – and this, in turn, ensures injection occurs quickly and without necessary precautions, ultimately leading to greater health risks such as HIV infection or abscesses. In the Dominican Republic, and particularly in the neighborhood of Capotillo, abuses by the authorities are commonplace, and street-based drug users are the most frequent victims.

In Figure 7,“Cacería de culpables” (Hunting the guilty ones), the photographer uses graffti from Capotillo to illustrate public protest against police abuse, which often accompanies an accusation of using illegal substances. Pictured on the wall in the upper-right corner of the image is the clearly written phrase, “Policia no me ponga droga” (police don’t plant drugs on me), echoing comments we have heard routinely in our ethnographic research that the police often plant drugs on individuals to justify arrest. The lower photograph reinforces this message of protest through the depiction of a defiant community member, using an image from the US invasion of 1965 as a metaphor for oppression.

Figure 7.

Cacería de culpables/Hunting the guilty ones.

Analysis: The community raises its voice against corruption. Many protests against the mistreatment and abuse of authority demonstrate an evil that continues growing. Alternatives: Sensitizing the police corps. Better pay and treatment of the police to improve their work. Empowerment and citizen oversight to fight injustice.

These images express the outrage we often heard from drug users which is particularly acute among addicts who are the most likely to experiences such abuses. In our ethnographic research in Capotillo, we also heard stories of police violence and corruption that are consistent with these depictions. Importantly, many of the addicts described pervasive violence perpetrated by other community members, demonstrating that such abuses extend beyond the police. In one case occurring early in our fieldwork, a street-based drug user arrived to seek emergency attention from the head of a local harm reduction organization we were interviewing, and was bleeding profusely from his ear, which a community member had severed in retaliation against the man’s alleged theft to support his habit. Shocking stories of brutal beatings, stabbings and extrajudicial killings of homeless drug users in Capotillo circulate in these communities, demonstrating a logic of social cleansing behind such crimes, many of which remain uninvestigated and unresolved.

Figure 8, “Barvarismo e intolerancia” (Barbarism and intolerance), dramatically presents an example of this kind of abuse, presenting the burned face and torso of an addict who was burned by community members. The caption connects such barbarous acts to the routinized “social violence” and dehumanization that provides the symbolic justification for their enactment. Here, as with cases of injection wounds, the burned body becomes a site for the inscription of social wounds inflicted by the moral indignation with which drug users are typically received, and the embodied suffering that is reproduced through such social violence.

Figure 8.

Barvarismo e intolerencia/Barbarism and intolerance.

Analysis: The results of addiction can be rejection and social violence. The community commits inhuman acts like burning people as punishment. Alternatives: Community education to reduce collective violence. Don’t take justice into your own hands.

Conclusion

Proyecto Lentes allowed us to tie our goal of documenting the narratives and experiences of vulnerable groups to applied outcomes by incorporating a methodology of group reflection and analysis into an ethnographic project. PhotoVoice permitted the Proyecto Lentes team to amplify the voices of persons struggling with addiction in an experience-near format that provoked critical reflection and, perhaps, has the potential to contribute to a shift in Dominican drug policy from a purely punitive model to one emphasizing harm reduction approaches. As illustrated through the example images and captions presented above, the activist-artists selected images and constructed narratives intended to address specific policy gaps and needs. Indeed, the project has been effective at translating community voices of drug users into a format capable of reaching policy audiences. As Proyecto Lentes has moved into the exhibition phase, we have shown the work at numerous sites in the Dominican Republic such as the Consejo Nacional de Control de Drogas (The National Council for Drug Control), the School of Public Health at the Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, several local high schools, in the lobby of the Sixth Latin American Conference on Drug Policy, and various community organizations. Exhibits continue at the time of this writing, including several exhibitions in Miami, Florida, USA.

As described in the introduction, part of our scientific goal is to identify best practices for incorporating PhotoVoice into an ethnographic project informed by CMA. PhotoVoice and CMA are complementary in that they both provide frameworks for drawing connections between local experiences or vernaculars, such as the “curita” (little cure) that motivates drug-seeking among the heroin users we studied, and the complex social and structural factors that are most salient to the health and rights of populations, such as the punitive Dominican drug law 50–88. The PhotoVoice approach also complements CMA in that it incorporates a form of critical pedagogy, fostering reflection on the causes of social ills and identifying means of addressing them. The ethnographic methods of participant observation and the flexible approach to fleldwork typical of anthropology are also apt for combination with PhotoVoice methodology, allowing the ethnographer to ground the analysis in the perspectives and words of community members. In addition, we found that the institutional ethnography of drug treatment policies and programs was highly synergistic with the PhotoVoice analysis, since both of these described similar social processes using slightly different language and media, allowing us to triangulate perspectives and contribute to more grounded ethnographic representations.

Our project also speaks to central debates in the study of “visual culture”, in particular the capacity of visual representations to express and, in turn, shape the contours of social inequalities. Cultural studies theorists such as Paul Gilroy (1987) have examined the social work that visual images can do, for example, in perpetuating racial stereotypes or drawing upon and reinscribing difference. Gillian Rose, in her discussion of the critical visual culture approach, has remarked on the capacity of visual representations to provoke critical understandings that might rupture or disrupt societal hierarchies or inequalities (Rose, 2012). Such approaches to visual methods have strong synergies with the social justice impetus of PhotoVoice as it was used in this project, as a means of representing pathogenic “social ills” and tracing their immediate consequences for individual bodies and communities. The captions created by the artists further reinforce the images with reflections on these social ills, leveraging the power of the images to capture audiences affectively while canalizing particular critical interpretations. We believe this illustrates perfectly the potential role of visual methods such as PhotoVoice in applied medical anthropological projects such as ours.

An additional goal of our project was to demonstrate the ways that PhotoVoice can be adapted to active drug using populations for whom daily survival is a struggle, not to mention the obligations that come with the collaborative development of a long-term photographic exhibit or the potential hazards and challenges of using cameras in drug use spaces. We described several techniques we used to adapt the method to this context, including: the creation of a familial social environment that transcended the purely practical and became a source of support and conflict resolution; the linkages of the project to a harm reduction organization (FUNDOREDA) that provided a central location for contacting this hard-to-reach population; the provision of clothes and food as a part of a community-led initiative; and the use of the project to provide professionalization opportunities for drug users. We believe the Proyecto Lentes provides a useful example for the adaptation of PhotoVoice to active drug using populations.

In this context, we would like to end with a mention of the unexpected effects on the seven participants who completed the project over two years of implementation. In addition to participating in regular trainings that required a sense of commitment and provided a certain structure to what are often the chaotic realities of addiction, these individuals have subsequently led numerous exhibitions and told their stories at conferences, and more recently the group has proposed to conduct a school-based program using the exhibition as part of an educational curriculum on drug policy and harm reduction. At the time of this writing, they are finalizing a brochure to describe their exhibition to local teachers. Some of the team members have sought drug rehabilitation or decided to pursue educational training. While we did not set out to formally evaluate the impact of Proyecto Lentes on the activist-artists themselves, our observations support the use of participatory photography and pedagogical methods such as PhotoVoice as both a means of political analysis and as an empowerment intervention for street-based drug users.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following members of the ‘Familia FotoVoz’: Amancio Vidal Agramonte, Ruby Cornielle, Isidro Guzmán, Leika Rondón Lara, Carlos Martínez, Mabel Mercedes Mejía, Álvaro Vásquez, Albarelis Caraballo Mota and Sherlo Otniel Canela. We thank Federico Mercado, Director of Fundoreda, for his support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA 1 R01 DA031581-01A1; PI: Mark Padilla], a K02 award for Nelson Varas-Díaz [1K02DA035122], and a Supplement to Support Diversity in Health-Related Research for Jose Colón-Burgos [3R01DA031581-03S1]. Also, the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center at Florida International University provided support for non-personnel expenses.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the funders.

References

- Agozino B. Drug and alcohol consumption and trade and HIV in the Caribbean: A review of the literature. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Diseases. 2014 January;:1–12. doi: 10.17303/jaid.2014.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biehl J. Vita: Life in a zone of social abandonment. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bobea L. Organized and disorganized crime: Muertos legales and ilegales in the Caribbean. ReVista: Harvard Review of Latin America. 2012;XI:56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. The moral economies of homeless heroin addicts: Confronting ethnography, HIV risk, and everyday violence in San Francisco shooting encampments. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:2323–2351. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgois P. Righteous dopefiend. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brotherton D, Barrios L. Banished to the homeland: Dominican deportees and their stories of exile. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova D, Parra-Cardona R, Blow A, Johnson DJ, Prado G, Fitzgerald HE. ‘They don’t look at what affects us’: The role of ecodevelopmental factors on alcohol and drug use among Latinos with physical disabilities. Ethnicity & Health. 2015;20:66–86. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2014.890173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day M. A situational assessment of responses to HIV and drug use from a harm reduction and rights-based perspective in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, Kingston, Jamaica, and Port of Spain, Trinidad. National HIV/AIDS Commission Barbados; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.hivgateway.com/files/3b915779c120ae65bca97dd2cac4eaa6/Harm_Reduction_Assessment_with_technical_revisions_mpd.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum Publishing Company; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy P. ‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack’: The cultural politics of race and nation. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Graham LF, Matiz A, Lopez W, Gracey A, Snow RC, Padilla M. Addressing economic devastation and built environment degradation to prevent violence: A photovoice project of Detroit Youth Passages. Community Literacy Journal. 2013;8:41–52. doi: 10.1353/clj.2013.0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harley D. Perceptions of hopelessness among low-income African-American adolescents through the lens of photovoice. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2015;24:18–38. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2014.915780. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helm S, Lee W, Hanakahi V, Gleason K, McCarthy K, Haumana Using photovoice with youth to develop a drug prevention program in a rural Hawaiian community. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2015;22:1–26. doi: 10.5820/aian.2201.2015.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mmari K, Blum R, Sonenstein F, Marshall B, Brahmbhatt H, Venables E, … Sangowawa A. Adolescents’ perceptions of health from disadvantaged urban communities: Findings from the WAVE study. Social Science and Medicine. 2014;104:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Organización de los Estados Americanos (OEA), Comisión Interamericana para el Control del Abuso de Drogas (CICAD), & Consejo Nacional de Drogas de la República Dominicana (CND) Proyecto sobre el estado del problema de deroína en la República Dominicana. Project about the state of the heroin problem in the Dominican Republic. 2013. Retrieved from the Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission http://www.cicad.oas.org/oid/pubs/ProyectoHeroina_Informe_RepublicaDominicana.pdf.

- Padilla M, Colon-Burgos J, Varas-Diaz N, Matiz-Reyes A, Parker C. Tourism labor, embodied suffering, and the deportation regime in the Dominican Republic. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. doi: 10.1111/maq.12447. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pindera C. Unpublished master’s thesis. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba; 2003. Through the eye of a needle: Women injection drug users in Winnipeg. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Singer M, Bourgois P, Friedman SR, Strathdee SA. The social structural production of HIV risk among injecting drug users. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1026–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. London: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. Beyond the ivory tower: Critical praxis in medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1995;9:80–106. doi: 10.1525/maq.1995.9.1.02a00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upegui-Hernández D, Torruella RA. Humillaciones y abusos en centros de “tratamiento” para uso de drogas en Puerto Rico [Humiliation and abuse in drug treatment centers in Puerto Rico] Puerto Rico: Intercambio Puerto Rico; 2015. May, [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC. Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women’s health. Journal of Women’s Health. 1999;8:185–192. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior. 1997;24:369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]