Abstract

Background

To explore experiences of parents of children with disabilities using the WWW, roadmap, a tool to support them in exploring needs, finding information, and asking questions of professionals and to explore differences between parents who had used the WWW‐roadmap to prepare for consultation with their rehabilitation physician and parents who had not.

Methods

In a sequential cohort study, we included 128 parents; 54 used the WWW‐roadmap prior to consultation and 74 received care‐as‐usual. Both groups completed questionnaires after consultation, assessing empowerment, self‐efficacy, parent and physician satisfaction, family centredness of care, and experiences using the tool. Additionally, 13 parents were interviewed.

Results

Parents who used the WWW‐roadmap looked up more information on the Internet. No other differences between parents and physicians were found. In the interviews, parents said that the WWW‐roadmap was a useful tool for looking up information, exploring and asking questions, and maintaining a comprehensive picture.

Conclusion

Using the WWW‐roadmap prior to consultation did not improve self‐efficacy, satisfaction, or family centredness of care. Findings suggest positive experiences regarding factors determining empowerment, creating conditions for a more equal parent–physician relationship.

The WWW‐roadmap is useful for parents to explore their needs and find information, but more is needed to support empowerment in consultations.

Keywords: consultation; family, centred care; family empowerment; information; paediatric rehabilitation

Key messages.

Parents and families are unique in their needs regarding the care for their child.

The WWW‐roadmap is a tool that can be used by parents to explore their needs and search for information.

Using only the tool does not change parental empowerment or the way a consultation is experienced.

Supporting empowerment requires more than providing information.

1. INTRODUCTION

Parents of children with disabilities play a major role in the way their child functions. They are the experts on the way their child and family function and should thus be seen as partners in the care process. In paediatric rehabilitation, these family‐centred principles have been around for several decades now, but professionals as well as parents still struggle to shift focus towards real family‐centred services (Bailey, Raspa, & Fox, 2012; Darrah, Wiart, Magill‐Evans, Ray, & Andersen, 2012; MacKean, Thurston, & Scott, 2005). Acknowledging the uniqueness of families, assessing their individual and current family needs is key to addressing these needs (Bailey & Simeonsson, 1988; G. King, Williams, & Hahn Goldberg, 2017; Terwiel et al., 2017). Parents should be empowered to express their needs and the focus should be shifted towards the family as a whole. Parental empowerment is defined as “[…] the acquisition of motivation […] and ability […] that patients might use to be involved or participate in decision‐making, thus creating an opportunity for higher levels of power in their relationship with professionals” (Fumagalli et al., 2015).

Although parents value initiatives that support their empowerment (van der Pal et al., 2014), few tools, methods, and interventions to support empowerment and family‐centred services are available (Anderson & Funnell, 2010; G. King et al., 2017).

Important determinants in the process of empowerment are being sufficiently informed and having the skills that make them feel more able to be involved in decision making (Fumagalli et al., 2015). Previous research showed that parents generally experience a lack of information (Alsem, Ausems, et al., 2017; Cunningham & Rosenbaum, 2013). Because of the variety of family needs and information needs and the changes in such needs over time, it is a challenge to provide targeted information in daily rehabilitation practice.

In cocreation with parents, professionals, IT specialists, and researchers, we have created a digital tool that aims to help parents explore their needs, find information, and put their questions to the appropriate professionals. This tool is called the WWW‐roadmap (WWW‐wijzer in Dutch). The Ws stand for “What do I want to know?,” “Where can I find information?,” and “Who can help me further to answer my questions?” Parents can use the tool as a means to prepare for consultations with a rehabilitation professional but also in their daily lives as a source of information. The process of developing the tool has been described elsewhere (Alsem, van Meeteren, et al., 2017).

The present study explored parental and physicians' experiences with the WWW‐roadmap, as well as differences between parents who had used the WWW‐roadmap to prepare for a consultation with their rehabilitation physician and parents who had not, in terms of empowerment and self‐efficacy, parental and professional satisfaction with the consultation and family centredness of care.

2. METHOD

The study was conducted in 15 Dutch rehabilitation practices in different settings. Settings included rehabilitation centres, university hospitals, and schools for children with special needs. Inclusion started in April 2016 and was completed in June 2017. In all phases of the project, there was close collaboration between researchers and parents (Alsem, van Meeteren, et al., 2017). The study protocol was evaluated by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht, the Netherlands (Study ID: 15/585), and approved by all local ethical committees of the participating centres.

2.1. Procedures

We used a posttest only sequential cohort design. All successive parents with an upcoming appointment with their rehabilitation physician were approached by telephone by the researcher or the secretary of the rehabilitation physician. After permission, parents were contacted to provide them with additional information on the study and to ask for written informed consent. In each team, the first 10 parents were allocated to the control group, and the next 10 parents to the intervention group. Before their consultation with the rehabilitation physician, parents in the intervention group received written information about the WWW‐roadmap, including instructions for its use and a login code for the WWW‐roadmap whereas parents in the control group did not receive this information. In both groups, the consultation itself was “as‐usual,” meaning that neither the rehabilitation physician nor the parents received specific instructions. After the consultation, the parents as well as the physician were asked to fill in a questionnaire regarding the consultation (see outcome parameters). Furthermore, a random sample of parents from the intervention group were asked to participate in a semistructured interview in order to assess their experiences with the tool and the possible effects on the consultation. Because empowerment is a very individually determined process, we decided that further qualitative exploration was necessary.

2.2. Participants

The 15 rehabilitation physicians that helped including parents were asked for their experiences. Parents were included as follows.

Inclusion criteria:

Parents of children (0–21 years) with a disability

Having a face‐to‐face appointment with a physician during the inclusion period

Exclusion criteria:

Parents with insufficient understanding of the Dutch language and thus not being able to use the WWW‐roadmap

Parents unable to use a computer (or tablet/smartphone) with Internet connection

2.3. Sample size

At the time of development of the study, no similar studies using the Family Empowerment Scale (FES) as the primary outcome measure were known, so it was not possible to perform a reliable power calculation. We calculated that within the time frame of our study, we would be able to include two groups of 75 parents, which we anticipated to be sufficient to explore differences between parents who used the tool and those who did not. For the qualitative study, interviews were continued until data saturation was reached.

2.4. Intervention

Parents were asked to use the WWW‐roadmap prior to their consultation with their rehabilitation physician. Parents can use the WWW‐roadmap to identify possible family needs, find reliable information on these topics, both in the tool and through references to Internet resources, and place unmet needs on a question prompt list. Moreover, the tool provides tips on how to prepare for a consultation with a physician. Parents were asked to use the WWW‐roadmap as much as they wanted. They decided for themselves when and how they wanted to use it.

2.5. Outcome parameters

To explore differences between parents who used the WWW‐roadmap and parents who did not, we used different questionnaires:

2.5.1. Primary outcome

The primary outcome was family empowerment, which was assessed using the Dutch adaptation of the FES (Koren, DeChillo, & Friesen, 1992). The FES is a 34‐item questionnaire designed to measure empowerment in families of children with emotional, behavioural, or mental disorders and has been used before in paediatric rehabilitation research (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016). It consists of three domains: the family (FES‐F; 12 items), children's services (FES‐S; 12 items), and parental involvement in the community (FES‐C; 10 items) and refers to three expressions of empowerment: attitudes, knowledge, and behaviours. It has good psychometrical properties (Singh et al., 1995). The FES has been translated into Dutch. With the consent of the developers, the domain of “parental involvement in the community” was removed from the Dutch version, because this domain was considered too culturally determined and not applicable to the Dutch situation (Kruijsen‐Terpstra et al., 2016). To gain a deeper understanding of parental experiences of empowerment in the intervention group, it was further explored in the interviews.

2.5.2. Secondary outcomes

Self‐efficacy in the consultation

Parental self‐efficacy was measured using the Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interactions (PEPPI‐5) scale (Maly, Frank, Marshall, DiMatteo, & Reuben, 1998). The PEPPI‐5 assesses parental confidence for five items, using a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from not confident at all to very confident. The Dutch PEPPI‐5 has demonstrated adequate validity and reliability in patients with osteoarthritis (ten Klooster et al., 2012).

Patient and physician satisfaction with the consultation

Patient and physician satisfaction were measured using the seven‐question Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ; Zandbelt, Smets, Oort, Godfried, & Haes, 2004). Following Albada et al., we added an item on satisfaction with shared decision making and overall satisfaction (Albada, van Dulmen, Spreeuwenberg, & Ausems, 2015). The PSQ has a patient and a professional version, asking the same questions from a patient's and professional's perspective. The original PSQ uses a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scale, but we decided to use a 7‐point Likert scale from not at all satisfied to extremely satisfied. The means of all seven items were computed.

Family‐centred services

The family centredness of the rehabilitation services as perceived by the parents was assessed using the Measure of Processes of Care (MPOC‐56; S. M. King, Rosenbaum, & King, 1996; S. King, Rosenbaum, & King, 1995). The MPOC measures the extent to which certain family‐centred behaviour or action takes place. For our study, we modified the Dutch version of the MPOC‐56 (van Schie, Siebes, Ketelaar, & Vermeer, 2004) in order to assess family centredness of the most recent consultation with the rehabilitation physician, instead of the past year. The original MPOC and the Dutch version have sound psychometric properties (S. M. King et al., 1996; van Schie et al., 2004).

Experiences with the consultation and WWW‐roadmap

A short questionnaire on the parents' experiences with the consultation was designed to assess possible differences between the two cohorts of parents. It consists of eight questions about asking for and receiving information and about asking questions. The rehabilitation physicians were also asked about their experiences with the consultation.

In order to assess general experiences with the WWW‐roadmap, we developed a 20‐item questionnaire for the parents. The questions focus on practical experiences (e.g., “The WWW‐roadmap helped me prepare for the consultation”) and the use of the WWW‐roadmap (e.g., “The WWW‐roadmap is easy to use”). Parents could answer these questions using a 7‐point Likert scale from 0 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). We aggregated the answers in three groups: “Agree,” “Neutral,” and “Disagree.”

Interview

The interview involved open‐ended questions based on predefined topics (see Appendix A) in which parents were asked about their experiences with the tool, the possible effects of using the tool, and about their views on involvement and empowerment during the consultation.

2.6. Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23. The similarity of the two groups at baseline was checked by means of independent t tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, and χ2 tests. Because most data were skewed, χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to describe differences between the two groups and in subgroups. In view of the multiple testing, α was set at ≤.01.

Parental experiences were explored qualitatively using a theoretic thematic analysis approach for the interview data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The data were imported into the NVIVO 10 software program to facilitate data analysis. Data were coded and analysed independently by two researchers (M. A. and J. B.), using open coding, followed by axial coding using a constant comparative approach. Discrepancies were discussed between M. A. and J. B. Codes and themes were identified by M. A. and J. B. and discussed with all authors. Member checking was performed by asking parents their opinion of the interpretation of the qualitative results.

3. RESULTS

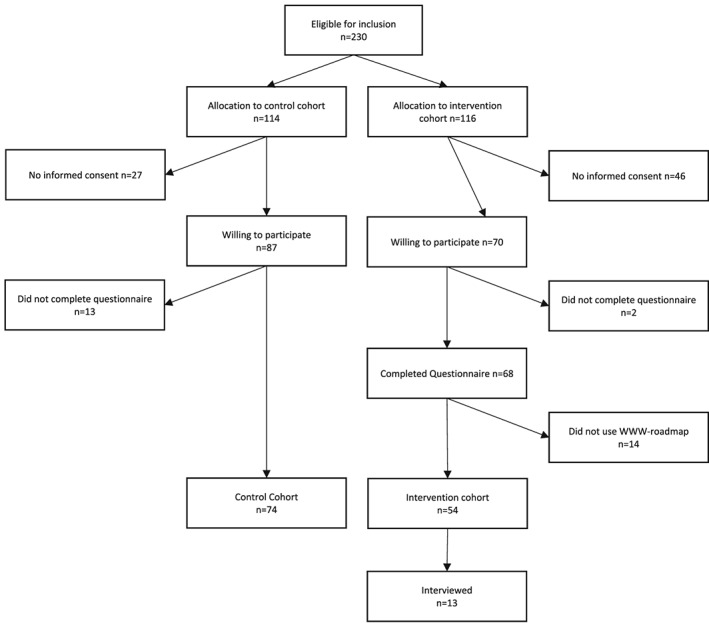

A total of 230 parents were asked to take part in the study (114 for the control group and 116 for the intervention group); 142 parents filled in the questionnaires. In the intervention cohort, 14 parents did not use the WWW‐roadmap and were excluded, leaving 128 questionnaires for analysis. Thirteen parents from the intervention group were asked to take part in a semistructured interview (Figure 1: flowchart).

Figure 1.

Flowchart

Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographics and patient characteristics between the groups.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| Characteristics | Control group | Intervention group | Qualitative study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | N | Mean | Diffa | N | Mean | |

| % | % | % | |||||

| Total N = 128 | 74 | 54 | 13 | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| In years (SD) | 7.7 (4.3) | 7.6 (4.3) | NS$ | 8.1 (4.3) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Boy | 50 | 67.6 | 32 | 59.3 | NS# | 7 | 53.8 |

| Girl | 24 | 32.4 | 22 | 40.7 | 6 | 46.2 | |

| Diagnosis | |||||||

| CP | 17 | 23.0 | 14 | 25.9 | NS# | 3 | 23.1 |

| Neuromuscular | 6 | 8.1 | 1 | 1.9 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Metabolic disorder | 3 | 4.1 | 3 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Genetic disorder | 7 | 9.5 | 2 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Spina bifida | 5 | 6.8 | 6 | 11.1 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Various syndromes (e.g., Down) | 11 | 14.9 | 6 | 11.1 | 3 | 23.1 | |

| Movement disorder | 7 | 9.5 | 5 | 9.3 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 8.1 | 10 | 18.5 | 3 | 23.1 | |

| Other | 12 | 16.2 | 7 | 13.0 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Mobility | |||||||

| Walks without limitations | 27 | 36.5 | 26 | 48.1 | NS# | 7 | 53.8 |

| Walks but unable to climb stairs | 24 | 32.4 | 13 | 24.1 | 4 | 30.8 | |

| Walks short distances with walking aid | 4 | 5.4 | 2 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Uses wheelchair | 12 | 16.2 | 5 | 9.3 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| No means of independent movement | 7 | 9.5 | 8 | 14.8 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Regular toddler group | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | NS# | 0 | 0.0 |

| Therapeutic toddler group | 14 | 18.9 | 5 | 9.3 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Regular daycare centre | 4 | 5.4 | 2 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Regular school | 19 | 25.7 | 18 | 33.3 | 5 | 38.5 | |

| Special needs education | 26 | 35.1 | 19 | 35.2 | 6 | 46.2 | |

| Special daycare centre | 7 | 9.5 | 4 | 7.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 3 | 4.1 | 6 | 11.1 | 1 | 7.7 | |

| Parental characteristics | |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| In years (SD) | 40.3 (6.0) | 39.0 (5.8) | NS$ | 39.0 (6.3) | |||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 7 | 9.5 | 6 | 11.1 | NS# | 1 | 8.0 |

| Female | 67 | 90.5 | 48 | 88.9 | 12 | 92.0 | |

| Nationality | |||||||

| Dutch | 74 | 100.0 | 52 | 96.3 | NS# | 13 | 100.0 |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single parent | 7 | 9.5 | 5 | 9.3 | NS# | 0 | 0.0 |

| Partner, not living together | 1 | 1.4 | 4 | 7.4 | 2 | 15.0 | |

| Married | 66 | 89.2 | 45 | 83.3 | 11 | 85.0 | |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than secondary school | 2 | 2.7 | 2 | 3.7 | NS# | 7 | 54.0 |

| Secondary school | 14 | 18.9 | 4 | 7.4 | 1 | 8.0 | |

| More than secondary school | 58 | 78.4 | 48 | 88.9 | 5 | 38.0 | |

| Family characteristics | |||||||

| Mean number of siblings (SD) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.4 (0.9) | NS$ | 1.3 (1) | |||

| Child is first child | 25 | 33.8 | 23 | 42.6 | 7 | 53.9 | |

| Consultation characteristics | |||||||

| First consultation | 18 | 24.3 | 5 | 9.3 | NS# | 0 | 0.0 |

| Follow‐up consultation | 56 | 75.7 | 44 | 81.5 | 13 | 100.0 | |

| Duration of the consultation | |||||||

| Estimated by physician, in minutes | 45.2 (12.3) | 44.4 (11.2) | NS$ | 43 (11) | |||

Abbreviation: NS, not significant, using $: t tests and #: χ2.

Differences between control and intervention cohort.

3.1. Using the WWW‐roadmap

Parents in the intervention group used the WWW‐roadmap 1–5 times before the consultation (mean 1.4, SD 0.75). Fourteen parents did not use the WWW‐roadmap at all. The time spent using the WWW‐roadmap ranged from 5 to 60 min (mean 18, SD 11).

3.2. Primary outcome

Scores on the FES were high in both groups, with large interquartile ranges. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups for either of the domains. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Differences between parents that used the WWW‐roadmap and parents who did not

| Measure | Possible range | Control group | Intervention group | P valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 25% | 75% | Median | 25% | 75% | |||

| Parents | ||||||||

| FES‐family | 0–5 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 4.3 | .1 |

| FES‐care | 0–5 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.5 | .9 |

| PEPPI‐5 | 0–25 | 22.0 | 19.0 | 25.0 | 21.0 | 20.0 | 25.0 | .93 |

| PSQ‐parents | 1–7 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 7.0 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 6.9 | .33 |

| MPOC enabling and partnership | 1–7 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 5.8 | .06 |

| MPOC providing general information | 1–7 | 4.2 | 3.0 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 5.0 | .48 |

| MPOC providing specific information about the child | 1–7 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 5.8 | .02 |

| MPOC comprehensive and coordinated care | 1–7 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 5.7 | .02 |

| MPOC respectful and supportive care | 1–7 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 6.1 | .15 |

| Before I visited the doctor, I had a clear question in mind. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 6.75 | .31 |

| I prefer to get all the information at an early stage. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .25 |

| I was given enough time to ask questions about matters that related to my child. | 1–7 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | .65 |

| Before going to see the doctor, I looked up information on the Internet. | 1–7 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 7.0 | .01 |

| During the consultation, the doctor answered all my questions or referred me to someone who could. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.25 | 7.0 | .02 |

| The topics that were important to me were discussed during the consultation with the doctor. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | .11 |

| I know to which professional I can turn with my questions. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.25 | 7.0 | .14 |

| I know where to find information if I have a question. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 | .30 |

| Physicians | ||||||||

| PSQ‐professionals | 1–7 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6.0 | .59 |

| These parents had a clear question in mind about the help they were seeking before they came to see the doctor. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .094 |

| I got the idea that these parents had looked up information on the Internet before the consultation. | 1–7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | .254 |

| The information that these parents had found appears to be reliable. | 1–7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | .147 |

| I know what information I have to give to these parents. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .452 |

| As these parents had many questions, I needed much time to explain. | 1–7 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 5.0 | .766 |

| These parents found it difficult to distinguish between major and minor aspects. | 1–7 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | .553 |

| I have been able to discuss all the matters that I thought were important during the consultation. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .168 |

| I was able to give these parents targeted information. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .480 |

| I have been able to satisfactorily answer all the questions these parents had. | 1–7 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | .993 |

Note. Significant results are bold.

Abbreviations: FES, Family Empowerment Scale; MPOC, Measure of Processes of Care; PEPPI‐5, Perceived Efficacy of the Patient–Physician Interaction; PSQ, Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Using Mann–Whitney U tests.

3.3. Secondary outcomes

3.3.1. Parents

Parents who used the WWW‐roadmap were more likely to say that they had looked up information on the Internet prior to the consultation (P = .01). We found no differences between the control and intervention groups regarding the scores for the other questions, nor for the PEPPI‐5, PSQ, and the MPOC.

3.3.2. Rehabilitation physicians

There were no differences between the intervention and control groups regarding the physicians' experiences or satisfaction with the consultation (see Table 2). Moreover, there was no difference between the two cohorts in mean duration of the consultation as estimated by the physician.

3.3.3. Parental opinions of the WWW‐roadmap

Table 3 shows parents' opinions about the WWW‐roadmap. Although most parents said that they had already had questions for the rehabilitation physician, 40.8% of the parents felt that the WWW‐roadmap had helped them come up with questions. The information provided in the WWW‐roadmap was considered reliable, and most parents found the WWW‐roadmap easy to use.

Table 3.

Parental opinions about the WWW‐roadmap

| Questions for parents about the use of the WWW‐roadmap | Agreea | % | Neutrala | % | Disagreea | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‐ The WWW‐roadmap is easy to use. | 33 | 67.3 | 5 | 10.2 | 11 | 22.4 |

| ‐ After I had read the user instructions for the WWW‐roadmap, I had enough information to be able to get started with the WWW‐roadmap. | 36 | 73.5 | 8 | 16.3 | 5 | 10.2 |

| ‐ The layout of WWW‐roadmap is attractive. | 30 | 61.2 | 9 | 18.4 | 10 | 20.4 |

| ‐ Before I used the WWW‐roadmap, I already had a clear question to ask the doctor. | 33 | 67.3 | 8 | 16.3 | 8 | 16.3 |

| ‐ The WWW‐roadmap has helped me think of other topics about which I wanted wore information. | 20 | 40.8 | 15 | 30.6 | 14 | 28.6 |

| ‐ The WWW‐roadmap gave me new ideas for questions I had not thought of before. | 20 | 40.8 | 13 | 26.5 | 16 | 32.7 |

| ‐ Using the WWW‐roadmap made it clearer to me what questions I wanted to ask the doctor. | 12 | 24.5 | 17 | 34.7 | 20 | 40.8 |

| ‐ Some questions in the WWW‐roadmap are too confrontational. | 2 | 4.1 | 14 | 28.6 | 33 | 67.3 |

| ‐ The WWW‐roadmap provided me with a comprehensive idea of the topics that might be discussed during a consultation with the doctor. | 31 | 63.3 | 9 | 18.4 | 9 | 18.4 |

| ‐ The use of the WWW‐roadmap yields too many questions for me. | 9 | 18.4 | 8 | 16.3 | 32 | 65.3 |

| ‐ As a result of my using the WWW‐roadmap, more attention was given to our family as a whole during the consultation with the doctor. | 5 | 10.2 | 19 | 38.8 | 25 | 51.0 |

| ‐ The explanations provided with the questions were generally clear. | 37 | 75.5 | 9 | 18.4 | 3 | 6.1 |

| ‐ The explanations provided with the questions were generally complete. | 33 | 67.3 | 11 | 22.4 | 5 | 10.2 |

| ‐ I trust the information provided in the WWW‐roadmap. | 40 | 81.6 | 9 | 18.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ‐ The information in the WWW‐roadmap is difficult to understand. | 2 | 4.1 | 12 | 24.5 | 35 | 71.4 |

| ‐ The WWW‐roadmap helped me prepare for the appointment with the doctor. | 19 | 38.8 | 14 | 28.6 | 16 | 32.7 |

| ‐ I feel that using the WWW‐roadmap makes it easier for me to ask the doctor questions. | 10 | 20.4 | 11 | 22.4 | 28 | 57.1 |

| ‐ The “shopping list” in the WWW‐roadmap provides an easy way to take my questions along when we go see the doctor. | 14 | 28.6 | 22 | 44.9 | 13 | 26.5 |

| ‐ As a result of the tips in the WWW‐roadmap, I have looked for answers to my questions in other sources. | 6 | 12.2 | 12 | 24.5 | 31 | 63.3 |

| ‐ I will use the WWW‐roadmap again in the future to prepare for the consultations with the doctor. | 16 | 32.7 | 16 | 32.7 | 17 | 34.7 |

Values add up to 49 due to missing values.

3.4. Post hoc analyses

To see whether specific subgroups of parents might have experienced additional benefit of the WWW‐roadmap, we explored differences between the cohorts in various subgroups: parents of older children (>4 years) versus parents of younger children and parents of children with and without an older sibling. We did not find significant differences between the subgroups on any of the measures.

3.5. Qualitative results

We used qualitative interviews in order to further explore parental experiences with and opinions on using the WWW‐roadmap as a preparation for the consultation and the process of empowerment. Parental quotes are presented in Table 4. The codes in brackets in the text refer to the quotes in Table 4.

Table 4.

Parental quotes

| Theme | No | Quote | Parent no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empowerment | E1 | Yeah, if it's about the nature of the conversation, I think, erm, that if I'm in control, that I then, sort of, decide where the conversation goes. That I very much control the conversation, like, this is what we are going to discuss. | 6 |

| E2 | I'm all for the idea of teamwork. If as a parent you are very much in control, you might miss things, as the rehabilitation physician sees these things every day. That goes for me too, but from a totally different perspective, with only the one child. | 1 | |

| Information | I1 | And then it's good if it all comes together in one place. As it's really a jungle, like how does this all work. With all these aids and play therapy and other therapies what not. | 4 |

| I2 | It's nice the way it's put on paper, but things often do not work that way in practice. And that's what I've come across most in recent years. | 7 | |

| I3 | Like having a sort of safety net available; if I come across something I can have a look. | 12 | |

| Asking questions | A1 | So, in that sense I think it's really convenient to have a list of questions. It's very pleasant, to sort of have both sides remained concentrated. I always recommend people who ask me questions, like, well you know so much about it now, just make a list. Cos people are nervous at that moment and they forget question number two. And then I'll go back and say doctor I still have one or two questions. Can I ask them? | 11 |

| A2 | What I found amusing is that you could make a shopping list. That you actually write down questions. I always get, that I'm with the doctor, and then I think what was it again. And then I just happen to have forgotten my note. | 6 | |

| A3 | Well, it does help you to check “Have I covered all topics?” that you want to discuss. As it does inspire you about the topics you could discuss with the rehabilitation physician. | 4 | |

| A4 | I'm sometimes a bit unsure whether I'm not asking too many questions. But that does not stop me from asking those questions anyway. So, it does sort of tell me, like, OK, I'm not the only one, and there are so many parents like me and it's good that I ask them. | 6 | |

| A5 | It could be that questions are already answered in the WWW‐roadmap, so that I have fewer questions. Or it could indeed function as a source of inspiration to think of some more questions than you had. | 13 | |

| Roles in the consultation | R1 | We discussed that with the physiotherapist and we'll be seeing the paediatrician on Monday. And she said “talk about it there too” and then I think … in my view she just deals with organs. | 4 |

| R2 | In a way it's because of the WWW‐roadmap that I thought, like, I can just ask my questions. The doctor is just another person, and he is not necessarily placed above me. And that's something that became very clear in the WWW‐roadmap. Like, the doctor's place is beside you, not above you. | 6 | |

| R3 | I think that if you go there unprepared, so not the kind of conversation we are having now, that you'll get stuck. And then you know, if you are not prepared, you'll have no questions. So that means that the doctor will automatically more or less take control. So, I think that if you have the WWW‐roadmap at hand at that moment, and so you have some questions of your own, you then also do certain things. | 13 | |

| Having a comprehensive picture | C1 | I now perhaps felt a bit more secure about my shopping list as I had checked all these areas once again. | 9 |

| C2 | I want to be involved in the choices that are made. To be taken seriously, for my own experiences. I do get the feeling that that's happening, by the way. But I do not have to be the doctor, or the medical expert | 9 | |

| Efficacy of the WWW‐roadmap | W1 | Answering the question whether “being in control” has changed after using the WWW‐roadmap: Well, not this time, but that's to some extent because I've gradually taken more control over the past 17 years and I know where to find everything. | 5 |

| W2 | I'm sure that if I'd had it at the start of the whole process, the WWW‐roadmap would have given me a lot of control, cos if I, like, look back on the past, and what I had to do to find everything out. […] And then if you look at this WWW‐roadmap, it's all much more available. Yeah, the things you want to find out you'll find in the end. That would have given me more control at the start, and also, like, have made me feel more at ease. | 5 |

3.5.1. Empowerment and involvement in the consultation

Parents described that the process of empowerment was a process they all went through, but they had different conceptions of what constitutes empowerment and involvement. Parents described this process as getting more control over their situation, at home as well as in the care process and during the consultation. Parents regarded an equal relationship with their physicians as important but at the same time reported that the (desired) degree of involvement changed all the time, especially at times of transition, for example, from preschool to primary school. Other factors that parents mentioned as determining the degree of control and thus the role taken during the consultation were information, involvement, and the attitude of the physician. Preparing for the consultation by determining their needs and looking for information helped the parents follow their own agenda during the consultation [E1].

At a more relational level, the parents described trust, reciprocity, and openness as conditions for their involvement in the consultation. In order to feel more empowered, parents needed to know that someone had a comprehensive picture of the situation. Knowing that no aspects are overlooked helped them feel more empowered [E2].

3.5.2. The WWW‐roadmap and the consultation

In the interviews, we identified themes relating to possible mechanisms by which the WWW‐roadmap could play a role in enhancing parental empowerment. The four themes that were identified were information, asking questions, roles in the consultation, and maintaining a comprehensive picture of the situation.

3.6. Information

Being informed was very important for parents. The WWW‐roadmap provided parents with information on the topics of interest to them. Although the parents had different opinions regarding the required level of detail of the information, the information in the WWW‐roadmap was considered reliable and relevant [I1]. Parents made a distinction between types of information. They reported that general information was provided in the WWW‐roadmap, but many of them wanted more specific information about the situation of their child [I2]. Because the parents' needs changed, especially during periods of transition, they found it important to be referred to sources where they could look up information [I3].

3.7. Asking questions

Parents found it hard to ask questions and were unsure which questions to ask. The WWW‐roadmap helped them formulate their questions. Most of the parents used a list of questions they made up beforehand [A1]. The WWW‐roadmap helped the parents complete their question prompt list [A2]. Parents felt supported by the themes and questions presented in the WWW‐roadmap [A3]. Using the WWW‐roadmap also helped to reassure the parents that they were asking all their questions [A4]. One parent mentioned that using the WWW‐roadmap could increase the number of questions but could also solve certain questions so they did not have to ask them [A5].

Traditionally, it is the physician who asks questions during the consultation, but by preparing their own agenda and topic list, the parents felt that more equal roles were created in the consultation. One parent suggested that both parents and physician could prepare for the consultation more effectively if they knew what the other was going to ask.

3.8. Roles in the consultation

Parents used the WWW‐roadmap to determine which professional to put their questions to, as they did not always know the expertise of all disciplines involved [R1]. The parents described different roles that they could adopt during the consultation. Using the WWW‐roadmap helped them in becoming aware of these possible roles [R2]. The parents also described that preparing for the consultation is a good way to become more involved, as they then knew which questions to ask [R3].

3.9. Maintaining a comprehensive picture

Preparing for the consultation helped parents take a more active role in the consultation. Because the questions included in the WWW‐roadmap cover many topics, parents were less afraid to forget to address a specific topic [C1].

Maintaining a comprehensive picture of their situation helped parents become more involved. On the other hand, one mother said that the level of involvement was limited by their knowledge and experience. Although most parents wanted to be involved in decision making, they differed in the degree of involvement they desired [C2].

3.9.1. Experiences using the WWW‐roadmap

Although different positive aspects of the WWW‐roadmap were mentioned, the parents also described barriers to using the tool. The barrier mentioned most was time. Parents are very busy managing their family and caring for their child, and using an extra tool was experienced by some as too time consuming.

Using the tool helped the parents prepare for the consultation and made them feel reassured. However, their perception was that it did not change the consultation or their roles during the consultation [W1]. Several parents mentioned that the WWW‐roadmap would have helped them at an earlier stage, when their child was younger, and they had less knowledge about the development of their child and the health care system [W2].

4. DISCUSSION

We explored differences between parents who used the WWW‐roadmap prior to a consultation with a rehabilitation physician and parents who did not. Parents in both groups had relatively high average scores on all outcome measures. Parents who had used the WWW‐roadmap reported that they had looked up more information on the Internet prior to the consultation. We did not find differences in outcome measures in terms of empowerment, self‐efficacy, parents' and physicians' satisfaction, and perceived family centredness of services. However, the results of the interviews showed that parents were positive about their experiences with the WWW‐roadmap and about various aspects of empowerment, giving an overall impression that using the tool might help them prepare for a consultation. The WWW‐roadmap seems to support parents in finding information, formulating questions, and determining the degree of involvement in consultations with their physicians. Influencing the process of empowerment and involving parents in the consultation apparently requires more than needs assessment, informing, and helping parents ask questions.

4.1. Influencing parental empowerment

Much has been written on parents' requirements for being more empowered and thus possibly involved in the care process of their child (Joseph‐Williams, Elwyn, & Edwards, 2014). It is not only knowledge and skills but also motivation and opportunities to truly participate in care which play major roles (Fumagalli et al., 2015). In this respect, it is not only parental preferences but also the preferences, motivation, and skills of the professionals that play a role in empowerment and the degree of parental involvement in consultations.

The main aim of our study was to explore the degree of support by the WWW‐roadmap that parents experience in making them feel more empowered in their relationship with professionals. However, parents' and professionals' assumptions about the expected “normal” roles are not always similar and could form an important barrier for empowerment (Joseph‐Williams et al., 2014). In other words, it is not only the parents' preparation for the consultation in terms of needs assessment and information provision that is important but personal and interactional factors and the perception of influence from the perspectives of both parents and professionals also play a role in determining the actual involvement.

Because parents vary considerably in the way they would like to access information (Gilson, Bethune, Carter, & McMillan, 2017), and not all parents can use a computer and connect to the Internet, we acknowledge that a digital tool is not useful for all parents.

The time spent and the frequency of using the WWW‐roadmap varied between parents. It is possible that the parents who spent more time using the WWW‐roadmap felt more supported by its functionalities (dose‐effect relation). We did not find this relation in our exploration of subgroups, but most parents used the WWW‐roadmap only once or twice.

In addition to personal factors and preferences, linguistic aspects also play a role. There is a substantial group of parents who do not have sufficient command of Dutch and can thus not benefit from the WWW‐roadmap. In other words, “one size does not fit all.” However, as part of a “toolbox” of different interventions and instruments that could support parental empowerment and involvement, the WWW‐roadmap can be used in a targeted manner by professionals in specific cases. The goals of using the tool and the instructions for its use could be introduced more explicitly to parents, to create better and more tailored opportunities for involvement in consultations.

4.2. Empowerment: It takes two to tango

We invited parents to use the WWW‐roadmap with little further explanation, and we did not ask the professionals to change their consultations. If parents are to become more involved in their child's care process, health care professionals should have the skills and motivation to involve them in the process. We therefore suggest that professionals should be motivated to explicitly discuss the use of the WWW‐roadmap if the parents are capable of doing so.

Although parents need both substantive knowledge and knowledge of their own preferences to participate in shared decision making (Joseph‐Williams et al., 2014; G. King et al., 2017), the perceived influence and desired role of parents should be explicitly established in order to enhance parental empowerment. This means that professionals should assess the best way to help parents in this process and in taking control of their situation.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

We analysed the responses of 128 parents of children with different disabilities, at different ages and in different health care settings, regarding their consultations with their physicians. Given the naturalistic setting of the study, its external validity seems acceptable. However, the sample size limited the possibilities for subgroup analysis.

Establishing a causal effect of the WWW‐roadmap would require a randomized, blinded longitudinal study. This would not be possible in our setting, because of possible contamination. Physicians could be triggered by parents who had used the WWW‐roadmap to give extra attention to their information search, family needs, and empowerment. Hence, we decided to perform a posttest only sequential cohort study. This provided us with the opportunity to explore differences between the groups, but not causality.

Only 10% of the respondents in our study sample were fathers. Possibly, fathers and mothers of children with disabilities have different needs and modes of engagement and empowerment (Hartley & Schultz, 2015; Pelchat, Levert, & Bourgeois‐Guérin, 2009). Future studies should further assess these differences and take them into account.

4.4. Improving the tool

Despite the above limitations, we know from the experiences of parents in the qualitative study and earlier feedback from parents (Alsem, van Meeteren, et al., 2017) that the tool could serve a purpose for a specific subgroup of parents. Our qualitative study and earlier feedback have revealed several aspects that might be improved. Parents not only need “objective” information but also like to share and find experience‐based knowledge (Alsem, Ausems, et al., 2017). Offering the opportunity to find and share this type of information would enhance the tool's efficacy. Parents also mentioned that it would be useful to add the option of sending their questions to the professional before the consultation, so that the professional could also prepare for the consultation. Besides improving the tool, greater attention for the process of implementation and use in daily practice could also enhance its effects. Better implementation in the care process, including an introduction to and coaching on the use of the tool, could enhance its effect. Having the WWW‐roadmap available at a moment that suits them most, instead of this being dictated by a study, would also be more in line with the principles of family‐centred care.

5. CONCLUSION

Using the WWW‐roadmap to prepare for consultations did not result in quantitatively measurable differences in parental empowerment, self‐efficacy, satisfaction, or family centredness of care. However, our qualitative study did reveal some of the perceptions and experiences of parents and the possible effects on different aspects of involvement and empowerment before and during the consultation.

In view of these findings, and the feedback we had received in earlier stages (Alsem, van Meeteren, et al., 2017), we conclude that the WWW‐roadmap is able to support parents in formulating their needs and finding information irrespective of whether they are preparing for consultations with professionals. Implementation should be further investigated to optimize the tool's clinical efficacy.

5.1. Practice implications

Parents who have access to the Internet, a sufficient command of the Dutch language, and time to prepare for consultations with their physician could use the WWW‐roadmap to explore their needs and find information. Professionals could consider recommending the WWW‐roadmap to eligible parents for these purposes. Instruments to enhance parent involvement and empowerment should not only focus on information provision but also address issues at a more interactional level between parents and professionals.

5.2. Informed consent and patient details

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. We confirm that all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the AGIS Zorginnovatiefonds, Revalidatiefonds, Johanna Kinderfonds, and the Stichting Rotterdams Kinderrevalidatie Fonds Adriaanstichting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First, we would like to thank all parents who took part in our study. We want to thank Emmeke Faas for her help in interviewing the parents, as well as Monique van Groenestijn and Nicole Romijn for their work in typing out the interviews. We would also like to thank Sandra van Dulmen for her feedback on and suggestions for the design of the study. We wish to thank the Dutch Association of People with Disabilities and their Parents (BOSK) for their input in all phases of the study. Finally, we would like to thank all physicians and their secretaries for helping to recruit parents and their assistance in other aspects of the study.

APPENDIX A. TOPIC LIST INTERVIEWS WITH PARENTS

Introduction (5 min)

Explain who you are and what we are studying

Tell about the goal of this interview

Explanation about the goal of the interview

-

‐

Study on the use of the www‐roadmap in practice, and what the consequences are for the visit to the doctor.

-

‐

You have already completed the questionnaire. Sometimes questions will look alike, but now there is opportunity to explain answers.

-

‐

These interviews are also aimed at further exploring a few issues from the questionnaire.

Confidentiality

-

‐

The results of the interview will be processed in coded form. Your doctor and the treatment team do not know what you have told. The statements therefore have no influence on the treatment of your child.

-

‐

The results are used to gain insight into the experiences with the www‐roadmap. Possibly an article can be written about it, whereby the statements can not be traced to the person.

Explanation of the interview

-

‐

The interview will last about an hour.

-

‐

If you have questions, you can always ask them directly.

-

‐

We are especially curious about your experiences.

-

‐

We will start the interview by checking a number of data, then I have some questions in advance, but it is not a questionnaire as you may be used to. It is the intention that you mention all experiences and tell all the ideas. All input is welcome!

Permission recording equipment

-

‐

We would like to include the interview on this sound recorder. So that I can better listen to you and do not have to write everything down. Are you okay with that?

-

‐

Get the device and switch it on if this permission has been obtained.‐ If there are no further questions, I would like to start the interview.

The interview (30–40 min).

The following list of questions is intended as a guide or at the end as a checklist, not to be asked literally.

Preparation of the consultation: Information seeking, preparation, and asking questions.

Extent of questions: How did you use the WWW‐roadmap, did the WWW‐roadmap help you prepare for the consultation?

How do you normally prepare a consultation with the doctor (without using the WWW‐roadmap)?

How did you prepare the last consultation (using the WWW‐roadmap)?

Were there differences? What was different?

Which part of the WWW‐roadmap did you mainly use?

What part/aspects of the WWW‐roadmap did it help the most?

Do you feel that you are better informed because you have used the WWW‐roadmap?

Have there been any questions that were resolved before you went to the doctor?

- Is the WWW‐roadmap an added value in preparation for the consultation?

- If yes, what added value?

Have you come to a “shopping list” in preparation for the consultation?

Has the WWW‐roadmap played a role in this?

What were barriers to using the WWW‐roadmap?

In future consultations, would you use the WWW‐roadmap again?

Do you have the confidence that you can get good information yourself? Has the WWW‐roadmap helped in this? Or can the WWW‐roadmap help with this?

During the consultation: Asking questions, involvement in the consultation, empowerment

What do you mean by involvement in the consultation?

What role do you want to have in this?

(In the longer term in the rehabilitation process) Has your role changed over time?

Who was in charge of the conversation?/Did you feel like you were in control?

- Do you need more control?

- Could the WWW‐roadmap influence the need for control?

- How? Should the WWW‐roadmap be changed to be able to help this?

- Did you feel that you had more control with the use of the WWW‐roadmap?

- How did the WWW‐roadmap help you with this?

- What in the WWW‐roadmap can/should be changed (or should be added) to have help you get involved in the consultation?

- Do you feel that you have enough opportunities to be involved in the consultation?

- Did the WWW‐roadmap help with this?

- What could help as a supplement or change in the WWW‐pointer to get more space to take control?

What do you need to get more control in the care process?

Did you use your shopping list? How?

Have you been able to ask everything you wanted to ask?

Has the doctor asked what you wanted to know?

Was there enough time?

Was it referred to someone else if the doctor could not answer the question?

If several consultations have taken place in one day: Has the WWW‐roadmap helped to split questions, did it help to ask questions to the right person?

Are you now asking other questions? Are you able to better formulate your questions?

Contents of the WWW‐roadmap

Are you missing information in the WWW‐roadmap?

What should be changed in the WWW‐roadmap?

Is the information in the WWW‐roadmap clear?

- What could help you to get information easier

- Specifically on the internet?

- During the consultation with the doctor?

Completion

These were the questions I wanted to ask you. Do you have any comments or would you like to mention other things?

-

‐

Thank you for participating in this study.

-

‐

Switch off the recording equipment and leave some room for comments.

-

‐

Make notes if necessary.

Alsem MW, Verhoef M, Braakman J, et al. Parental empowerment in paediatric rehabilitation: Exploring the role of a digital tool to help parents prepare for consultation with a physician. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45:623–636. 10.1111/cch.12700

REFERENCES

- Albada, A. , van Dulmen, S. , Spreeuwenberg, P. , & Ausems, M. G. (2015). Follow‐up effects of a tailored pre‐counseling website with question prompt in breast cancer genetic counseling. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(1), 69–76. 10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsem, M. W. , Ausems, F. , Verhoef, M. , Jongmans, M. J. , Meily‐Visser, J. M. A. , & Ketelaar, M. (2017). Information seeking by parents of children with physical disabilities: An exploratory qualitative study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 60, 125–134. 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsem, M. W. , van Meeteren, K. M. , Verhoef, M. , Schmitz, M. J. W. M. , Jongmans, M. J. , Meily‐Visser, J. M. A. , & Ketelaar, M. (2017). Co‐creation of a digital tool for the empowerment of parents of children with physical disabilities. Research Involvement and Engagement, 3(1), 26 10.1186/s40900-017-0079-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R. M. , & Funnell, M. M. (2010). Patient empowerment: Myths and misconceptions. Patient Education and Counseling, 79(3), 277–282. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D. B. , Raspa, M. , & Fox, L. C. (2012). What is the future of family outcomes and family‐centered services? Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 216–223. 10.1177/0271121411427077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D. B. , & Simeonsson, R. J. (1988). Assessing needs of families with handicapped infants. The Journal of Special Education, 22(1), 117–127. Retrieved from. http://sed.sagepub.com/content/22/1/117.abstract, 10.1177/002246698802200113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, B. J. , & Rosenbaum, P. L. (2013). Measure of processes of care: A review of 20 years of research. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 56(5):445–52 10.1111/dmcn.12347; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrah, J. , Wiart, L. , Magill‐Evans, J. , Ray, L. , & Andersen, J. (2012). Are family‐centred principles, functional goal setting and transition planning evident in therapy services for children with cerebral palsy? Child Care Health and Development, 38(1), 41–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, L. P. , Radaelli, G. , Lettieri, E. , Bertele, P. , Masella, C. , Bertele, P. , & Masella, C. (2015). Patient empowerment and its neighbours: Clarifying the boundaries and their mutual relationships. Health Policy, 119(3), 384–394. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, C. B. , Bethune, L. K. , Carter, E. W. , & McMillan, E. D. (2017). Informing and equipping parents of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 55(5), 347–360. 10.1352/1934-9556-55.5.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, S. L. , & Schultz, H. M. (2015). Support needs of fathers and mothers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1636–1648. 10.1007/s10803-014-2318-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph‐Williams, N. , Elwyn, G. , & Edwards, A. (2014, March). Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient‐reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling, 94, 291–309. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, G. , Williams, L. , & Hahn Goldberg, S. (2017). Family‐oriented services in pediatric rehabilitation: A scoping review and framework to promote parent and family wellness. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(3), 334–347. 10.1111/cch.12435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, S. , Rosenbaum, P. , & King, G. (1995). The measure of processes of care: A means to assess family‐centred behaviours of health care providers. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, Neurodevelopmental Clinical Research Unit. [Google Scholar]

- King, S. M. , Rosenbaum, P. L. , & King, G. A. (1996). Parents' perceptions of caregiving: Development and validation of a measure of processes. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 38(9), 757–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, P. E. , DeChillo, N. , & Friesen, B. J. (1992). Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37(4), 305–321. 10.1037/h0079106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruijsen‐Terpstra, A. J. A. , Ketelaar, M. , Verschuren, O. , Gorter, J. W. , Vos, R. C. , Verheijden, J. , … Visser‐Meily, A. (2016). Efficacy of three therapy approaches in preschool children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 58(7), 758–766. 10.1111/dmcn.12966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKean, G. L. , Thurston, W. E. , & Scott, C. M. (2005). Bridging the divide between families and health professionals' perspectives on family‐centred care. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 8(1), 74–85. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2005.00319.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly, R. C. , Frank, J. C. , Marshall, G. N. , DiMatteo, M. R. , & Reuben, D. B. (1998). Perceived efficacy in patient‐physician interactions (PEPPI): Validation of an instrument in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 46(7), 889–894. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat, D. , Levert, M.‐J. , & Bourgeois‐Guérin, V. (2009). How do mothers and fathers who have a child with a disability describe their adaptation/transformation process? Journal of Child Health Care, 13(3), 239–259. 10.1177/1367493509336684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N. N. , Curtis, W. J. , Ellis, C. R. , Nicholson, M. W. , Villani, T. M. , & Wechsler, H. A. (1995). Psychometric analysis of the family empowerment scale. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 3(2), 85–91. 10.1177/106342669500300203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ten Klooster, P. M. , Oostveen, J. C. M. , Zandbelt, L. C. , Taal, E. , Drossaert, C. H. C. , Harmsen, E. J. , & van de Laar, M. A. F. J. (2012). Further validation of the 5‐item Perceived Efficacy in Patient‐Physician Interactions (PEPPI‐5) scale in patients with osteoarthritis. Patient Education and Counseling, 87(1), 125–130. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwiel, M. , Alsem, M. W. , Siebes, R. C. , Bieleman, K. , Verhoef, M. , & Ketelaar, M. (2017). Family‐centred service: Differences in what parents of children with cerebral palsy rate important. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43(5), 663–669. 10.1111/cch.12460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pal, S. M. , Alpay, L. L. , van Steenbrugge, G. J. , Detmar, S. B. , van, d. P. , Alpay, L. L. , … Detmar, S. B. (2014). An exploration of parents' experiences and empowerment in the care for preterm born children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(6), 1081–1089. 10.1007/s10826-013-9765-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Schie, P. E. , Siebes, R. C. , Ketelaar, M. , & Vermeer, A. (2004). The measure of processes of care (MPOC): Validation of the Dutch translation. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30(5), 529–539. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00451.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandbelt, L. C. , Smets, E. M. , Oort, F. J. , Godfried, M. H. , & de Haes, H. C. (2004). Satisfaction with the outpatient encounter: A comparison of patients' and physicians' views. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 19(11), 1088–1095. https://doi.org/JGI30420 [pii], 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30420.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]