Abstract

To characterize current evidence and current foci of perioperative clinical trials, we systematically reviewed Medline and identified perioperative trials involving 100 or more adult patients undergoing surgery and reporting renal endpoints that were published in high impact journals since 2004. We categorized the101 trials identified based on the nature of the intervention and summarized major trial findings from the five categories most applicable to perioperative management of patients.

Trials that target ischemia suggest that increasing perioperative renal oxygen delivery with inotropes or blood transfusion does not reliably mitigate AKI, although goal-directed therapy with hemodynamic monitors appears beneficial in some trials. Trials that have targeted inflammation or oxidative stress, including studies of NSAIDS, steroids, N-acetylcysteine, and sodium bicarbonate have not demonstrated renal benefits, and high-dose perioperative statin treatment increased AKI in some patient groups in the two largest trials to date. Balanced crystalloid intravenous fluids appear safer than saline, and crystalloids appear safer than colloids. Liberal compared to restrictive fluid administration reduced AKI in a recent large trial in open abdominal surgery. Remote ischemic preconditioning, although effective in several smaller trials, failed to reduce AKI in two larger trials.

The translation of promising pre-clinical therapies to patients undergoing surgery remains poor, and most interventions that reduced perioperative AKI compared novel surgical management techniques or existing processes of care rather than novel pharmacologic interventions.

Keywords: kidney injury, trials, surgery, perioperative, treatment

Introduction

Postoperative AKI is common, estimated to affect 13% of patients undergoing open abdominal surgery and 25% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery.1 Postoperative AKI is associated with increased perioperative morbidity, including infection, lung injury, and delirium, and AKI is an independent predictor of a five-fold increase in perioperative mortality.2 Postoperative AKI is also associated with an increased risk for repeat AKI and the development of chronic kidney disease (CKD).3 Even when creatinine concentration return to baseline after AKI in these patients the increased renal and mortality risk remains.

Clinicians and scientists design clinical trials of both prophylactic and therapeutic strategies to limit the burden of AKI in patients undergoing surgery, to elucidate mechanisms of postoperative AKI, and to compare rates of AKI as a safety measure in studies of surgical or anesthetic techniques. Compared to non-surgical populations perioperative cohorts offer several unique benefits to trial design and execution. For example, cardiac surgery is common and provides adequate numbers of relatively homogenous patients to recruit, a relatively consistent renal insult with known timing, opportunities for adequate baseline measurements and prophylactic intervention, and opportunities to follow patients closely in the postoperative period.4

We therefore sought to examine the available literature to characterize the interventions reporting renal outcomes in perioperative clinical trials, summarize key findings from these trials, and offer conclusions about potential therapeutic opportunities for subsequent investigation.

Systematic Review

We conducted a systematic review of the literature seeking to identify all major perioperative clinical trials conducted in patients undergoing surgery that reported renal outcomes. The search strategy replicated that used in the recently published Standardized Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine (StEP) initiative that summarized existing renal endpoints used in published clinical trials and provided recommendations to standardize reporting of such endpoints.5 A Medline search was executed on August 20, 2019 to identify additional eligible randomized trials published since the June 16, 2016 search reported in the initial StEPs review. The initial StEPs review included studies published from January 1, 2004. We employed the same search logic and the same criteria for inclusion and exclusion of trials as previously described. In brief, we excluded trials not conducted in adults; where a surgical incision was not performed (e.g. endoscopic procedures); where the surgical procedure was renal transplantation, surgery to facilitate renal replacement therapy (RRT), or where a primary characteristic of the study cohort was preexisting end stage renal failure or RRT; specifically comparing a surgical intervention with a non-surgical intervention (e.g. percutaneous coronary intervention vs. coronary artery bypass); or including fewer than 100 patients. Consistent with the original StEPs methodology, studies including patients undergoing TAVR or EVAR were eligible for inclusion and additional analyses of previously published randomized trials were also considered eligible where the secondary analysis focused specifically on renal outcomes. As previously described, the search was restricted to the five journals with the highest impact factors from each of the following six International Web of Science™ categories, providing the impact factor of each of these journals was greater than three: Anesthesiology (Anesthesiology, British Journal of Anaesthesia, Anesthesia & Analgesia, Anaesthesia); Cardiac and Cardiovascular Systems (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Circulation, Circulation Research, Journal of the American College of Cardiology Cardiovascular Interventions); Critical Care Medicine (American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Chest, Intensive Care Medicine, Critical Care Med, Critical Care); General and Internal Medicine (New England Journal of Medicine, European Journal of Medicine, Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association, Annals of Internal Medicine, British Medical Journal); Surgery (Annals of Surgery, British Journal of Surgery, Journal of the American College of Surgery, Archives of Surgery, JAMA Surgery); and Nephrology (Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Kidney International (and Supplements), American Journal of Kidney Disease, Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation).5 Manuscripts retrieved from the updated search of these 30 journals were screened and included if they met inclusion criteria. Authors were also able to include additional trials not identified by the Medline search but meeting eligibility criteria and mutually agreed as appropriate for inclusion.

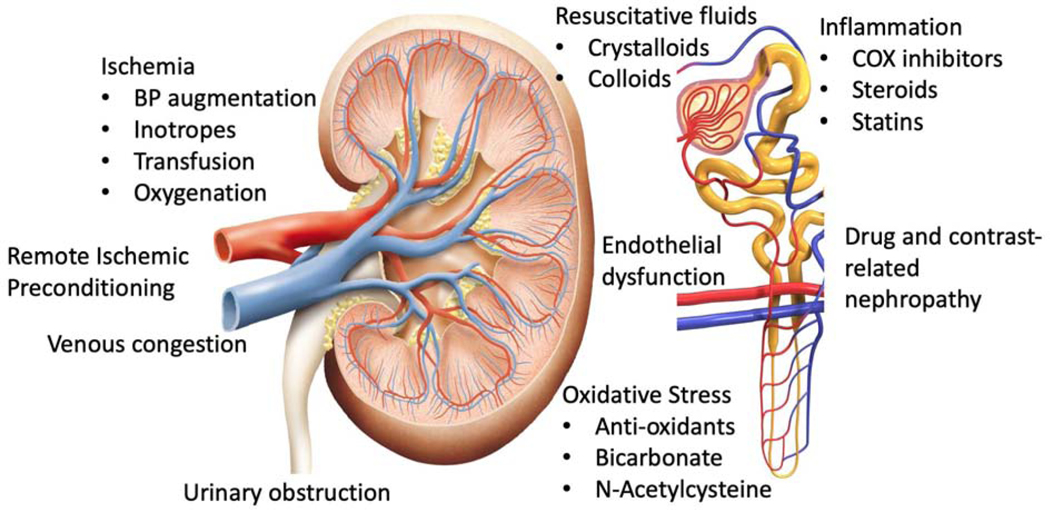

An additional 38 clinical trials were identified and added to the previously identified 63 trials (Table 1). One completed trial published in a journal not pre-specified in the search protocol6 was substituted in place of a pilot trial of the same study7 included in the previously reported StEPs review. To assess common themes, mechanisms of perioperative AKI and interventions to affect these mechanisms were considered (Figure 1). We then created eleven categories based on similarities of therapeutic interventions, and we assigned each study to one of these categories based on the intervention tested. For trials that could be included in more than one category, we chose one category.

Table 1.

Perioperative acute kidney injury clinical trials published in major journals, categorized by intervention

| Year | First author | Abbreviated title/topic | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | De Hert62 | Volatile vs. total intravenous anesthetic | Anesthetic technique |

| 2009 | Rohm63 | Sevoflurane vs. propofol | Anesthetic technique |

| 2010 | Song64 | Sevoflurane vs. propofol | Anesthetic technique |

| 2011 | Svircevic65 | Thoracic epidural anesthesia | Anesthetic technique |

| 2014 | Probst66 | Fast-track PACU vs. ICU postoperative management | Anesthetic technique |

| 2014 | Yoo67 | Sevoflurane vs. propofol | Anesthetic technique |

| 2016 | McGuinness69 | Hyperoxia vs. normoxia during CPB, SO-COOL | Anesthetic technique |

| 2016 | Smit70 | Moderate hyperoxic vs. physiologic oxygen targets | Anesthetic technique |

| 2016 | Cho68 | Dexmedetomidine | Anesthetic technique |

| 2018 | Canty71 | Cardiac ultrasound, ECHONOF-2 pilot | Anesthetic technique |

| 2005 | Burns87 | N-acetylcysteine in cardiac surgery | Antioxidants |

| 2008 | Sisillo88 | N-acetylcysteine in cardiac surgery | Antioxidants |

| 2010 | Hilmi89 | N-acetylcysteine in orthotopic liver transplantation | Antioxidants |

| 2013 | Haase6 | Sodium bicarbonate | Antioxidants |

| 2013 | McGuinness90 | Sodium bicarbonate | Antioxidants |

| 2016 | Soh91 | Sodium bicarbonate | Antioxidants |

| 2015 | Dangas105 | Bivalirudin vs. heparin in transcatheter AVR: BRAVO-3 | Coagulation |

| 2017 | Bilecen106 | Fibrinogen Concentrate | Coagulation |

| 2017 | Myles107 | Tranexamic acid, ATACAS | Coagulation |

| 2007 | Mentzer92 | Nesiritide, NAPA | Diuretic |

| 2010 | Sezai93 | Human atrial natriuretic peptide, NU-HIT | Diuretic |

| 2011 | Sezai94 | Human atrial natriuretic peptide, NU-HIT CKD | Diuretic |

| 2014 | Bove95 | Fenoldopam, FENO-HSR | Diuretic |

| 2017 | Barba-Navarro96 | Spironolactone | Diuretic |

| 2007 | Gandhi97 | Tight vs. loose glucose management | Endocrine |

| 2008 | Schetz98 | Tight vs. loose glucose management | Endocrine |

| 2009 | Subramaniam99 | Insulin infusion vs. boluses | Endocrine |

| 2012 | Pretorius100 | ACE-inhibitor vs. mineralocorticoid blocker vs. placebo | Endocrine |

| 2017 | Besch101 | Exenatide, ExSTRESS | Endocrine |

| 2014 | Skhirtladze81 | Albumin vs. 6% HES (130/0.4) vs. LR | Fluid |

| 2015 | Young82 | Buffered crystalloid vs saline, SPLIT | Fluid |

| 2016 | Lee83 | Albumin | Fluid |

| 2018 | Kammerer84 | 6% Hydroxyethyl Starch (130/0.4) vs. 5% Albumin | Fluid |

| 2018 | Myles85 | Liberal vs. restricted fluid, RELIEF | Fluid |

| 2018 | Semler86 | Balanced crystalloids vs. saline in ICU, SMART | Fluid |

| 2010 | Magder80 | Colloids vs. crystalloids | Fluid |

| 2005 | Nussmeier51 | COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib | Inflammation |

| 2012 | Dieleman52 | Dexamethasone, DECS | Inflammation |

| 2014 | Devereaux53 | Aspirin, POISE-2 | Inflammation |

| 2014 | Devereaux54 | Clonidine, POISE-2 | Inflammation |

| 2014 | Garg55 | POISE-2 AKI sub study | Inflammation |

| 2015 | Jacob56 | Dexamethasone, DECS AKI sub study | Inflammation |

| 2015 | Whitlock57 | Methylprednisolone, SIRS | Inflammation |

| 2016 | Billings58 | Atorvastatin, Statin AKI cardiac surgery RCT | Inflammation |

| 2016 | Zheng61 | Rosuvastatin, STICS | Inflammation |

| 2016 | Myles59 | Aspirin, ATACAS | Inflammation |

| 2016 | Park60 | Atorvastatin | Inflammation |

| 2004 | Sanders9 | Normovolemic hemodilution | Ischemia |

| 2004 | McKendry8 | Esophageal doppler flowmetry goal-directed therapy | Ischemia |

| 2005 | Wakeling10 | Esophageal doppler flowmetry goal-directed therapy | Ischemia |

| 2007 | Donati11 | Oxygen extraction goal-directed therapy | Ischemia |

| 2010 | Jhanji14 | Stroke volume vs. CVP goal-directed therapy | Ischemia |

| 2010 | Benes12 | FloTrac stroke volume goal-directed therapy | Ischemia |

| 2010 | Hajjar13 | Restrictive vs. liberal transfusion, TRACS | Ischemia |

| 2011 | van der Linden15 | MP4OX hemoglobin analogue in hip arthroplasty | Ischemia |

| 2012 | Challand16 | Intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in colorectal surgery | Ischemia |

| 2014 | Pearse17 | Goal-directed therapy in gastrointestinal surgery, OPTIMISE | Ischemia |

| 2015 | Murphy18 | Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery, TITRe2 | Ischemia |

| 2016 | Schmid19 | Intraoperative goal-directed therapy in abdominal surgery | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Landoni23 | Levosimendan, CHEETAH | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Futier21 | Individualized vs. standard blood pressure, INPRESS | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Mehta26 | Levosimendan, LEVO-CTS | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Hajjar22 | Vasopressin vs. norepinephrine, VANCS | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Meersch25 | KDIGO bundle in cardiac surgery, PrevAKI | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Cholley20 | Levosimendan, LICORN | Ischemia |

| 2017 | Mazer24 | Restrictive vs. liberal transfusion, TRICS III | Ischemia |

| 2018 | Gocze27 | KDIGO bundle in non-cardiac surgery, BigpAK | Ischemia |

| 2018 | Mazer28 | Restrictive vs. liberal transfusion, TRICS III at 6 months | Ischemia |

| 2019 | Garg29 | Restrictive vs. liberal transfusion, TRICS III AKI sub study | Ischemia |

| 2018 | Ederoth102 | Cyclosporine, CiPRICS | Novel therapeutic |

| 2018 | Himmelfarb103 | THR-184, a bone morphogenic protein-7, THRASOS | Novel therapeutic |

| 2018 | Swaminathan104 | Mesenchymal stem cells, ACT-AKI | Novel therapeutic |

| 2010 | Rahman72 | Remote ischemic preconditioning | RIPC |

| 2011 | Zimmerman73 | Remote ischemic preconditioning | RIPC |

| 2015 | Zarbock76 | Remote ischemic preconditioning, RenalRIP | RIPC |

| 2015 | Meybohm75 | Remote ischemic preconditioning, RIPHeart | RIPC |

| 2015 | Hausenloy74 | Remote ischemic preconditioning, ERICCA | RIPC |

| 2017 | Zarbock77 | Remote ischemic preconditioning, 90 day RenalRIP results | RIPC |

| 2018 | Song78 | Remote ischemic POSTconditioning | RIPC |

| 2019 | Zhou79 | Remote ischemic preconditioning | RIPC |

| 2004 | Prinssen30 | Open vs. endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, DREAM | Surgical technique |

| 2009 | Shroyer31 | Off- vs. on-pump coronary-artery bypass, ROOBY | Surgical technique |

| 2010 | Brown32 | Open vs. endovascular aortic aneurysm repair, EVAR 1 and 2 | Surgical technique |

| 2011 | Smith33 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, PARTNER trial | Surgical technique |

| 2012 | Zhu36 | Infrahepatic inferior vena cava clamping vs. low CVP | Surgical technique |

| 2012 | Budera34 | Atrial surgical ablation and atrial fibrillation, PRAGUE-12 | Surgical technique |

| 2012 | Lamy35 | Off- vs. on-pump coronary-artery bypass CORONARY at 30d | Surgical technique |

| 2013 | de Bruin37 | Open vs. endovascular aortic aneurysm repair DREAM at 5 yr | Surgical technique |

| 2013 | Ranucci40 | Intraortic balloon pump in coronary artery bypass, SCORE | Surgical technique |

| 2013 | Diegeler38 | Off- vs. on-pump coronary artery bypass, GOPCABE | Surgical technique |

| 2013 | Lamy39 | Off- vs. on-pump coronary artery bypass, CORONARY at 1yr | Surgical technique |

| 2014 | Garg41 | CORONARY renal function sub study at 1 year | Surgical technique |

| 2015 | Thyregod42 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, NOTION at 1 year | Surgical technique |

| 2016 | Leon46 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, PARTNER at 2 years | Surgical technique |

| 2016 | Deeb43 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, CoreValve at 3 years | Surgical technique |

| 2016 | Haussig44 | Cerebral device during transcatheter AVR, CLEAN-TAVI | Surgical technique |

| 2016 | Lamy45 | Off- vs. on-pump coronary artery bypass, CORONARY 5 yr | Surgical technique |

| 2017 | Mack47 | Cerebral device during surgical AVR | Surgical technique |

| 2017 | Reardon48 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, SURTAVI | Surgical technique |

| 2018 | Feldman49 | Mechanical vs. transcatheter AVR REPRISE III | Surgical technique |

| 2019 | Popma50 | Transcatheter vs. surgical AVR, Evolut low risk | Surgical technique |

CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; AVR, aortic valve replacement; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ICU, intensive care unit; RCT, randomized clinical trial; COX, cyclooxygenase; RIPC, remote ischemic preconditioning; CVP, central venous pressure.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms and related therapies for perioperative AKI. BP, blood pressure; COX, cyclooxygenase.

Twenty-two of the 101 trials targeted reduction of renal ischemia through techniques to increase oxygen delivery or alter hemodynamics.8–29 Twenty-one trials compared the effect of different surgical techniques on postoperative AKI.30–50 Eleven trials administered anti-inflammatory medications, for example aspirin or glucocorticoids, to affect perioperative inflammation.51–61 We included trials of statins in the anti-inflammatory category, even though statins are also reported to decrease oxidative stress and improve endothelial function. Ten trials compared different anesthetic techniques.62–71 Eight trials investigated the effects of remote ischemic preconditioning.72–79 Seven trials compared the effects of different intravenous fluids regimens.80–86 Six trials examined the effects of anti-oxidant therapies, including sodium bicarbonate.6,87–91 Five trials examined the effect of diuretics.92–96 Five trials examined endocrine modulation, such as insulin therapy or mineralocorticoid antoganism.97–101 There were three trials of novel therapeutics,102–104 and three trials of coagulation techniques (Figure 2).105–107

Figure 2.

Intervention categories and the number of trials in each of those categories, from the 101 perioperative clinical trials of AKI published in high-impact journals since 2004. RIPC, remote ischemic preconditioning.

We selected the most definitive trials in several categories, based on expert opinion, to summarize current evidence for reducing the burden of AKI in patients undergoing surgery. We did not pool the data from the studies in each category due to a high degree of heterogeneity among studies. We chose the categories of ischemia, inflammation, fluids, antioxidants, and remote ischemic preconditioning for this purpose. Some clinical conclusions of this review are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of best current evidence for prevention or treatment of perioperative AKI from trials targeting ischemia, inflammation, fluid management, oxidative stress, and remote ischemic preconditioning

| Intervention | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Ischemia | • Inotropes do not decrease AKI. • A lower threshold for transfusion (7.5 g/dl) does not increase AKI risk and limits exposure to allogenic blood and associated costs. • Individualized goal-directed therapy to maintain or augment oxygen delivery may decrease AKI in high-risk patients. |

| Inflammation | • NSAIDs/aspirin do not reduce AKI. • Corticosteroids do not routinely reduce risk for AKI although dexamethasone may have some benefits in patients with advanced CKD. • Statins do not reduce AKI and may increase AKI in patients with CKD. |

| Fluids | • A restricted fluid administration increased AKI in open abdominal surgery. • Chloride-limited fluid may decrease AKI compared to chloride rich fluid. • Synthetic starches increase risk of AKI compared to crystalloids in critically ill patient populations. |

| Oxidative stress | • N-acetylcysteine does not decrease AKI. • Sodium bicarbonate does not decrease AKI. |

| RIPC | • RIPC does not reliably decrease AKI, but additional studies in patients not receiving propofol are needed |

AKI, acute kidney injury; NSAIDS, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NAC, n-acetylcysteine; RIPC, remote ischemic preconditioning.

Ischemia

Perioperative renal ischemia is frequently implicated as a contributor to postoperative AKI, and manipulation of renal perfusion and oxygen delivery remains the most common intervention to reduce postoperative AKI. Maintenance of adequate oxygen tension throughout the kidney during the perioperative period is complex. Renal parenchymal oxygen tension is dictated by renal blood flow, the oxygen carrying capacity of blood, intrarenal vascular shunting, and parenchymal oxygen consumption. Even when renal oxygen delivery is maintained or augmented, portions of the kidney may be ischemic due to differential perfusion of the renal cortex and medulla. Most of the blood that perfuses the renal cortex is filtered at the glomeruli and does not perfuse the renal medulla. In addition, oxygen consumption is largely dictated by the energy requirements of tubular sodium chloride reabsorption, and increased renal blood flow increases glomerular filtration, sodium chloride reabsorption, and oxygen consumption. This may paradoxically increase renal ischemia.108 This physiology may explain in part why therapies that increase renal perfusion do not necessarily decrease ischemia throughout the kidney or reduce AKI. Nonetheless, hemodynamic indicators of poor systemic perfusion and oxygen delivery, including low blood pressure, low cardiac output, high central venous pressure, and anemia are all associated with increased risk of AKI. For these reasons, many studies for AKI prevention have been designed to limit renal ischemia by supporting or increasing blood pressure, augmenting cardiac output, transfusing packed red blood cells, and providing “goal-directed therapy.”

Blood pressure

Systemic blood pressure affects renal perfusion pressure, and intraoperative hypotension is an independent risk factor for the development and severity of AKI.109 Blood pressure in the perioperative period may be augmented by the administration of intravenous sympathomimetic vasopressors such as phenylephrine, ephedrine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and vasopressin. Based on recommendations to select a target intraoperative blood pressure according to a patient’s baseline pressure, Futier et al randomly assigned 298 patients undergoing major surgery lasting two or more hours to an individualized or standard intraoperative blood pressure management strategy.21 Patients assigned to the individualized strategy received a norepinephrine infusion to maintain systolic blood pressure within 10% of baseline, and patients assigned to the standard strategy received 6mg ephedrine boluses for any decrease in systolic blood pressure below 80 mmHg or 60% of baseline. The individualized blood pressure management group had higher intraoperative blood pressure and a lower rate of the organ injury composite outcome compared to the standard management group (38.1% vs. 51.7%, p=0.02), but rates of mild, moderate, and severe AKI were similar between groups.

Since different vasopressors have variable affinities for specific vasoactive receptors, vasopressors have differential effects on vascular tone, cardiac output, endocrine function, and renal function. For example, norepinephrine increases blood pressure by binding and activating alpha1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle and to a lesser extent beta1 receptors in the heart, while vasopressin increases blood pressure by binding and activating V1 receptors in vascular smooth muscle, but the pulmonary vasculature is relatively void of V1 receptors. Vasopressin also exerts antidiuretic effects, mediated by V2 receptors in the renal collecting system. Consequently, as compared to norepinephrine, vasopressin may increase systemic vascular resistance with less increase in pulmonary vascular resistance. This may have beneficial effects on cardiac function. The VANCS trial randomly assigned 330 patients with vasoplegic shock after cardiac surgery to norepinephrine or vasopressin treatment to maintain a mean arterial pressure of at least 65 mmHg.22 Vasopressin treated patients had a 10.3% rate of acute renal failure, defined using Society of Thoracic Surgery criteria,110 compared to a 35.8% rate among norepinephrine treated patients (p<0.001). Additional trials of perioperative vasopressin are needed.

Cardiac output

The kidneys receive approximately 20% of cardiac output and increasing cardiac output increases renal perfusion. Increased renal perfusion increases oxygen delivery to the kidneys and may reduce renal ischemia. Trials published in high impact journals have focused on the levosimendan, a calcium-sensitizing inotrope that increases cardiac output and promotes vasodilation. Levosimendan, however, is not currently approved by the FDA.

The CHEETAH trial randomly assigned 506 cardiac surgery patients with perioperative heart failure, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction less than 25%, intra-aortic balloon pump support, or high-dose inotrope support to a postoperative levosimendan infusion or placebo for 48 hours or until discharge from the ICU.23 Thirty-day mortality was not different between groups, nor were rates of mild, moderate, and severe AKI or renal-replacement therapy. The LEVO-CTS trial randomly assigned 849 cardiac surgery patients with baseline heart failure, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction less the 35% to an intraoperative levosimendan infusion that continued for a total of 24 hours or placebo.26 This treatment had no effect on the composite of 30-day mortality, renal-replacement therapy at 30-days, myocardial infarction at 5 days, or use of a mechanical cardiac assist device at 5 days nor any of the individual components of this composite endpoint. Similar to LEVO-CTS, the LICORN trial randomly assigned 335 cardiac surgery patients with baseline heart failure, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction less the 40% to an intraoperative levosimendan infusion that continued for a total of 24 hours or placebo and compared rates of persistent use of catecholamines postoperatively, need for mechanical assist device, and need for renal-replacement therapy during ICU stay.20 Fifteen levosimendan patients (9%) and ten placebo patients (6%) required postoperative renal-replacement therapy (p=0.16).

These trials of demonstrate that increasing renal perfusion does not decrease perioperative AKI or that any renal benefits of levosimendan-supported cardiac output are obviated by simultaneous deleterious effects.

Blood transfusion

Increasing the oxygen carrying capacity of blood remains an attractive technique to reduce perioperative renal ischemia and AKI. If blood flow to the corticomedullary junction, a site prone to injury, is limited, increased oxygen in the blood perfusing this site could have beneficial effects. The bulk of oxygen in blood is carried by hemoglobin, and scientists have experimented with increasing hemoglobin by transfusion of red blood cells and administering erythropoietin and iron. Blood transfusion, however, is not without risk. Transfusion can lead to lung injury, hemolysis, volume overload, immune modulation, and infection.111 Indeed, both anemia and intraoperative blood transfusion are established risk factor for postoperative AKI.112 For these reasons’ trials have focused on establishing safety thresholds for balancing the risks of anemia and transfusion.

Murphy and the TITRe2 Investigators randomly assigned 2007 patients immediately following cardiac surgery to packed red blood cells transfusion threshold of 9 g/dl (liberal) or 7.5 g/dl (restrictive).18 The liberal transfusion group received more blood transfusions and had higher hemoglobin during the postoperative period than the restrictive group. Clinical outcomes, including AKI, were similar between treatment groups. One hundred forty patients (14.2%) in the restrictive group and 122 patients (12.3%) in the liberal group suffered postoperative AKI (p=NS). Hajjar and the TRACS Investigators performed a similar study. They randomized 502 cardiac surgery patients to hematocrit thresholds of 30% vs. 24% for transfusion of packed red blood cells throughout the intraoperative and postoperative period.13 Mortality and renal failure requiring dialysis were not different between groups. Mazer and the TRICS investigators performed the largest perioperative trial of transfusion to date. They randomized 4860 cardiac surgery patients at moderate to high risk of death to intraoperative and postoperative transfusion thresholds of 9.5 g/dl and 7.5 g/dl.24 Once again, patients randomly assigned to the liberal transfusion group received more transfusions and had higher perioperative hemoglobin concentrations, but the rates of death (3.3%), stroke (2.0%), myocardial infarction (5.9%), and new-onset renal failure requiring dialysis (2.8%) were not different between groups. In the TRICS III kidney sub study, investigators compared the restrictive vs. liberal transfusion threshold intervention to mild, moderate, and severe AKI and confirmed that these two transfusion thresholds did not affect rates of postoperative AKI.29

These studies confirm that among patients undergoing cardiac surgery, a restrictive transfusion threshold of 7.5 g/dl results in fewer red blood cell transfusions than a liberal transfusion threshold of 9.5 g/dl without increasing risk of AKI.

Goal-directed therapy

Goal-directed therapy incorporates specific monitoring techniques to guide intravenous fluid and vasoactive agent administration to achieve specific hemodynamic goals. During and following surgery, anesthesia, fluid shifts, hemorrhage, positive pressure ventilation, or surgical manipulation of the cardiovascular system induce hemodynamic disequilibrium, and goal-directed therapy provides a logical and systematic means to manage patients based on real-time patient-specific data. Goal-directed therapy algorithms attempt to protocolize patient management techniques for perioperative physicians to use in routine practice. Common goals are maintenance of oxygen delivery through manipulation of blood pressure, cardiac output, and transfusion. Perioperative trials have largely focused on patients receiving intraabdominal surgery and, more recently, cardiac surgery.

Donati et al randomized 135 patients across nine hospitals scheduled for major abdominal surgery to maintain an oxygen extraction ratio (arterial hemoglobin oxygen saturation [SaO2] – central venous oxygen saturation [ScvO2]) less than 27% using fluid challenges, packed red blood cell transfusions, and a dobutamine infusion (treatment group), in addition to maintenance of mean arterial blood pressure > 80 mmHg, urine output > 0.5 ml/kg/min, and central venous pressure between 8–12 mmHg (control group) from induction of anesthesia to postoperative day 1.11 Central venous pressure, oxygen extraction ratio, and serum lactate were lower in the treatment group. Although seven of the 67 patients in the control group (10.4%) developed AKI, defined as a doubling of serum creatinine or initiation of renal-replacement therapy, compared to two of the 68 patients (2.9%) in the treatment group, this difference was not significant. In another trial of patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery Jhanji et al reported a 7.8% rate of AKI, defined by AKIN criteria, in 90 patients randomized to receive fluid boluses intended to maximize stroke volume (n=45) and in addition, a dopexamine infusion (n=45), compared to a 22% rate of AKI in 45 patients randomized to receive fluid boluses to maintain central venous pressure (p=0.03).14 These clinical effects were accompanied by improved sublingual and cutaneous microvascular blood flow, measured by sublingual microscopy and laser Doppler flowmetry.

Subsequent trials have not consistently demonstrated benefits of goal-directed therapy in patients undergoing surgery. Challand et al randomly assigned 179 patients undergoing colorectal surgery to intraoperative fluid administration guided by esophageal doppler to maximize stroke volume or to a “standard” fluid management strategy.16 Patients receiving this goal-directed therapy received a similar volume of fluid as patients receiving standard management but had increased stroke volume and cardiac index at the end of surgery. Outcomes between groups, including renal complications were similar between groups. The OPTIMIZE trial randomly assigned 734 high-risk patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery to a cardiac output–guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm for intravenous fluid administration and a dopexamine infusion or to usual care intraoperatively and for the first six hours postoperatively.17 A composite of major morbidity and death was not different between groups, and the rate of AKI was 4.6% in both groups. Schmid et al used a transpulmonary thermodilution PiCCO2® monitor to guide fluid, inotrope (dobutamine), and vasopressor (norepinephrine) management to maintain cardiac output and blood pressure.19 They randomized 180 patients receiving major abdominal surgery to an algorithm utilizing goal-directed therapy or to usual care intraoperatively and for the first 72 hours postoperatively. All patients received the PiCCO2® monitor. The total amount of fluids and vasopressors administered did not differ between treatment groups, although more dobutamine was used intraoperatively in the goal-directed therapy group. Treatment did not affect change in serum creatinine, creatinine clearance, or AKI defined using RIFLE or KDIGO criteria, which was approximately 50% in both groups. The authors attributed the lack of benefit of goal-directed therapy to the high achievement of hemodynamic goals in control group patients.

In patients undergoing cardiac surgery there is some evidence that postoperative goal-directed therapy may reduce the risk of AKI. Meersch et al implemented the KDIGO bundle for prevention of AKI in patients suffering renal stress post cardiac surgery, quantified by the product of urinary insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7 and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 2 (IGFBP7•TIMP-2 – NephroCheck® test) four hours after termination of cardiopulmonary bypass.25 Four hundred ninety-five of the 771 enrolled patients had a postoperative urinary IGFBP7•TIMP-2 concentration < 0.3 four hours after surgery and were excluded. Two hundred seventy-six patients had a postoperative urinary IGFBP7•TIMP-2 concentration > 0.3 and were randomly assigned to care based on the KDIGO bundle of nephroprotective recommendations or to usual care. Usual care specified maintaining mean arterial pressure >65 mmHg, central venous pressure between 8 and 10 mmHg, and initiation of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) once hemodynamically stable and hypertension occurred. The KDIGO bundle consists of avoiding ACEi, ARBs, nephrotoxins, and hyperglycemia for 72 hours and initiating a PICCO catheter-guided fluid management, inotrope, and vasopressor algorithm.113 The AKI enrichment strategy resulted in an overall KDIGO AKI rate of 63.4%, although most patients only met urine output criteria for AKI. Seventy-six of the 138 patients (55.1%) assigned to the KDIGO bundle developed AKI compared to 99 of the 138 patients (71.7%) assigned to usual care (p=0.004). Rates of moderate-severe AKI were also reduced in patients assigned to the KDIGO bundle (29.7%) compared to patients in the control group (44.9%, p=0.009). Rates of renal replacement therapy were not different between groups.

There is also some evidence that a goal-directed therapy may reduce postoperative AKI in non-cardiac surgery patients when a similar AKI-enrichment strategy is used. Gocze et al measured urinary IGFBP7•TIMP-2 in 237 high-risk patients following intrabdominal surgery at ICU admission and randomized the 135 patients who had IGFBP7•TIMP-2 values greater than 0.3 to postoperative management with the KDIGO bundle or usual care.27 Nineteen of the 60 patients (31.7%) assigned the KDIGO bundle developed AKI compared to 29 of the 61 patients (47.5%) assigned usual care (p=0.08). Differences between groups were more pronounced and statistically significant when comparing patients who had IGFBP7•TIMP-2 levels between 0.3 and 2.0 and when examining moderate or severe AKI.

Taking these trials together, the effect of perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy on AKI is inconclusive. Specific goals of goal-directed therapy and the methods used to achieve them vary between studies, and it is unclear whether or not efficacy may vary with the selection of goals and/or the methods used to achieve them. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the use of goal-directed therapy reduces postoperative AKI,114 most of the included trials were relatively small, and one of the largest included study, OPTIMIZE, found no effect on AKI. Results of the ongoing OPTIMZE II trial (ISRCTN39653756) are expected to significantly inform debate on this issue. The recent studies that showed benefits of the KDIGO bundle when applied to patients experiencing renal stress are promising. Larger studies are needed, however, and the significance of preventing AKI defined by oliguria alone remains unclear. It should be highlighted that no studies of goal-directed therapy have found harm in targeted hemodynamic management to optimize perfusion, and individualized patient management remains a key responsibility of perioperative physicians. The “usual care” that is provided in these trials for patients assigned to control groups also contains hemodynamic management guidelines individualized to patients – i.e., all patients receive some degree of goal-directed therapy. Physicians should continue to monitor and treat every patient to maintain renal perfusion and oxygenation, and formal goal-directed treatment algorithms may be beneficial.

Inflammation

Surgical trauma, ischemia-reperfusion, and pathogen exposure may all activate inflammation in perioperative patients, and this adaptive response facilitates repair of injured tissues and elimination of pathogens. Proinflammatory cytokines recruit neutrophils and macrophages to injured or infected tissue, and the magnitude of this response can elicit additional tissue and organ injury.115 Because inflammation is associated with AKI,116 inflammatory modulators including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), corticosteroids, and hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) have been investigated as potential therapies to prevent and decrease perioperative AKI.

NSAIDS

NSAIDS reduce inflammation by inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX) 1 or 2 and decreasing prostaglandin production. Although NSAIDS can contribute to AKI by dilating glomerular afferent arterioles, reducing glomerular filtration, or initiating interstitial nephritis, their anti-inflammatory effects have been explored as a potential therapy to reduce perioperative AKI. The Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE)-2 trial examined effects of aspirin or placebo and clonidine or placebo in 10,010 patients noncardiac surgery patients using a 2-by-2 factorial design.53,54 While the focus was on the antiplatelet effects of aspirin, acute kidney injury with dialysis was examined as a tertiary outcome and was marginally more likely in the aspirin group (OR, 1.75 vs. placebo [95% CI, 1.00–3.09]; p=0.05) but was not different in the clonidine group (OR, 1.26 vs. placebo [0.73–2.18]; p=0.41). A sub study of patients in this trial similarly found that neither aspirin nor clonidine increased risk of KDIGO stage 3 AKI nor receipt of dialysis.55 A key limitation of this trial was that creatinine was not measured per protocol, and measurements came only from routine care. The Aspirin and Tranexamic Acid for Coronary Artery Surgery (ATACAS) trial randomly assigned 2100 patients to continuation vs. discontinuation of aspirin before coronary artery bypass grafting. Renal failure was not different between aspirin and placebo treatment groups (OR, 1.20 [0.80–1.80]; p=0.81).59

Nussmeier et al randomized 1671 CABG patients randomized to the COX-2 inhibitor valdecoxib, its intravenous prodrug parecoxib, or placebo.51 Neither the incidence of dialysis nor the incidence of a serum creatinine concentration above 2.0 mg/dl with an increase of at 0.7 mg/dl differed between groups. Thus, there is no evidence from recent perioperative trials that NSAIDS or aspirin reduce AKI.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids reduce the production of inflammatory cytokines by suppressing eicosanoid production and inhibiting immune activation. Perioperative trials of corticosteroids have largely focused on patients receiving cardiopulmonary bypass because of the inflammatory response it elicits and the relatively high rate of AKI in this population. In the Dexamethasone for Cardiac Surgery (DECS) trial, 4494 on-pump cardiac surgery patients were randomized to high dose dexamethasone vs. placebo.52 Renal failure, defined using RIFLE criteria, was similar between treatment groups (RR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.44–1.14]). Interestingly, a post-hoc analysis of severe AKI in these patients found that dexamethasone reduced the risk of kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy (RR, 0.44 [95% CI, 0.19–0.96]; p=0.02).56 A limitation of this study was that 9 of the 28 patients that eventually required RRT suffered from preoperative AKI. The Steroids in Cardiac Surgery (SIRS) RCT randomized 7507 on-pump cardiac surgery patients to methylprednisolone or placebo and stratified randomization by pre-operative renal function. Methylprednisolone did not affect the primary composite outcome or renal failure in isolation (RR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.69–1.08]; p=0.2).57 Thus, there is not strong evidence that corticosteroids reduce AKI.

Statins

Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, commonly known as statins, affect several mechanisms underlying postoperative AKI including inflammation. These medications decrease circulating C-reactive protein117 and decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine levels.118 In the Statin AKI Cardiac Surgery RCT, 615 patients undergoing cardiac surgery were randomized to high dose atorvastatin vs. placebo, with randomization stratified by chronic kidney disease and diabetes.58 There was no difference in the rate of AKI in the 416 statin-using patients assigned atorvastatin vs. placebo (20.8% vs. 19.5%, respectively, p=0.75), nor among the statin-using CKD subgroup. Among the 199 statin-naïve patients, 21.6% of patients assigned atorvastatin suffered AKI compared to 13.4% of patients assigned placebo (p=0.15), and in statin-naïve patients with CKD, this effect was stronger (52.9% vs.15.6%, p=0.03). The Statin Therapy in Cardiac Surgery (STICS) trial randomized 1922 cardiac surgery patients to perioperative rosuvastatin and examined AKI at 48 hours as a secondary outcome. Rosuvastatin treatment did not affect the primary outcomes of atrial fibrillation or myocardial injury, but rosuvastatin increased the rate of AKI (24.7%), compared to placebo (19.3%, p=0.005).61 In another randomized trial of two hundred statin-naïve patients undergoing valvular heart surgery, atorvastatin treatment did not affect the rates of AKI or the blood concentrations of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) or interleukin-18 compared to placebo.60 In summary, perioperative statin administration does not prevent AKI and, in fact, may increase AKI in patients with preexisting CKD.

Fluids

The administration of intravenous fluid is ubiquitous in patients undergoing all but the most minor of surgical procedures. Several aspects of perioperative intravenous fluid administration have been implicated in the pathophysiology of perioperative AKI including volume of fluid administered (liberal vs. restrictive), electrolyte content of fluid (chloride-rich vs. chloride limited), and whether or not the administered fluid includes a molecule intended to increase oncotic pressure (crystalloid vs. colloid).

Liberal vs. restrictive fluid

Fluid depletion secondary to preoperative fasting, evaporative and other insensible perioperative fluid losses, vasoactive effects of anesthesia, inflammatory upregulation with increased capillary permeability and perioperative blood loss may all contribute to a disequilibrium of fluid homeostasis in the perioperative period, and administration of intravenous fluid has long been the centerpiece for maintaining adequate circulating blood volume to support stable hemodynamics and appropriate end-organ perfusion throughout this time. Insufficient fluid replacement may be associated with an increased likelihood for adverse perioperative outcomes such as AKI, likely a consequence of increased hemodynamic instability and decreased end-organ perfusion.119 Conversely, excess fluid replacement has also been considered a potential contributor to adverse outcomes such as AKI through increased venous pressure, disruption of the endothelial glycocalyx, and interstitial tissue edema.120 The non-compliant renal capsule may render the kidney susceptible to impaired perfusion in the setting of increased hydrostatic venous pressure, increased capillary leakage, and systemic hypotension.

Within this context numerous studies have attempted to address the issue of a liberal vs. restrictive perioperative fluid administration strategy.121 Although renal outcomes were not typically the focus of such trials, limited available evidence tended to support the overall benefits of a restrictive approach to fluid therapy. The majority of these studies were small, however, and interpretation was further complicated by a lack of standardization for definitions of liberal and restrictive. Recently, Myles et al published the RELIEF trial, a pragmatic, multi-center, international trial that randomized 3000 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery to either a liberal perioperative fluid strategy (approximately 3L of a balanced crystalloid during a 4 hour surgery and then 1.5 ml/kg/hr for at least 24 hours postoperatively) or a restrictive fluid strategy designed to provide ‘zero balance’ fluid status (approximately 1.5L of a balanced crystalloid during a 4 hour surgery and then 0.8 ml/kg/hr for at least 24 hours postoperatively).85 Results confirmed the expected inter-group separation in terms of volume of fluid administered but there was no difference in the primary endpoint of disability-free survival at 1 year postoperatively. Pre-specified secondary analyses identified a >70% increase in incidence of AKI in the those assigned to a restrictive fluid regimen as the only significant outcome difference between treatment groups. Importantly, this effect was consistently observed across all stages of AKI and was robust to multiple sensitivity analyses. However, measurement of renal function was restricted to the in-hospital period after index surgery and a follow-up study is ongoing to determine whether the short-term changes in renal function noted between groups translates into long-term changes in renal function and development of chronic kidney disease.

Chloride-rich vs. chloride-limited fluid

The chloride content of 0.9% saline and some colloid solutions is markedly greater than the normal physiological range of serum chloride in humans. The administration of these chloride-rich intravenous fluids is associated with hyperchloremia and a metabolic acidosis,122 but 0.9% saline remains a commonly administered perioperative intravenous fluid.123 Over the last decade, observational studies have consistently demonstrated an association between various metrics of an acute increase in serum chloride and adverse outcomes including AKI.124 Laboratory studies demonstrating that hyperchloremia produces renal vasoconstriction and reduces glomerular filtration provide a plausible mechanism by which chloride-rich intravenous fluid administration may exert a nephrotoxic effect.125 Despite these data, clinical trials limiting administration of chloride-rich fluids have produced conflicting results. The SPLIT trial, a cluster randomized, cluster cross-over, blinded trial in approximately 2200 patients (half of which were surgical) admitted to four ICUs, randomized patients to receive 0.9% saline (chloride concentration 150 mmol/L) or Plasmalyte-148 (chloride concentration 98 mmol/L).82 Saline vs. Plasmalyte treatment did not affect renal outcomes. However, the median volume of study fluid administered to participants was only 2000 ml, and significant amounts of fluid corresponding to the alternate study arm may have been administered in the 24 hours prior to study enrolment. No data were provided on observed differences in serum electrolytes or other biochemical parameters between groups to demonstrate that the study intervention impacted serum chloride levels. A subsequent open-label study in which perioperative fluid strategy alternated according to four pre-specified calendar cycles each of five months duration assigned more than 1100 patients undergoing cardiac surgery to receive either chloride-rich or chloride-limited fluid throughout their entire intraoperative and postoperative ICU course.122 Despite a median of almost five liters of fluid being administered to participants before the end of the first postoperative day and a clear difference in serum chloride levels and other biochemical parameters, there was no difference in renal outcomes between the two groups. However, the assignment of participants to fluid strategy was not randomized and there were some potentially important imbalances in prognostic factors between groups at baseline, limiting the strength of the results. More recently, Semler et al reported results of a pragmatic, cluster-randomized, multiple-crossover trial conducted in five ICUs (four of which were surgical ICUs) within a single academic center.86 ICUs were randomized to an alternating monthly administration of either 0.9% saline or a balanced salt solution. More than 15,000 participants were enrolled with a median volume of study fluid administration of approximately 1000 ml within 30 days of randomization. Serum chloride was approximately 1 mmol/L higher in the 0.9% saline group than the balanced salt solution group within the first 7 days after ICU admission. Assignment to receive a balanced salt solution compared to saline reduced the primary composite outcome of any major adverse kidney event within 30 days (MAKE30) from 15.4 to 14.3 percent (OR, 0.90 [95% CI 0.82–0.99]; p=0.04). Three large ongoing or unreported clinical trials addressing the impact of chloride-rich or chloride-limited intravenous fluid administration in approximately 28,000 patients (NCT02721654; NCT02875873; NCT02565420) will provide additional evidence.

Crystalloid vs. colloid fluid

Isotonic crystalloid fluids distribute throughout the extracellular fluid space (approximately 75% of which is extravascular). Colloid containing fluids, in contrast, contain macromolecules that limit their free movement across capillary membranes, potentially allowing for increased capillary oncotic pressure and a proportionately greater expansion of intravascular volume. Available colloid solutions consist of varying concentrations of human albumin (4%, 5%, 20%) or synthetic colloids (e.g., starch solutions). Long standing concerns regarding potential nephrotoxicity associated with starch solutions are supported by large randomized controlled trials such as the Crystalloid vs. Hydroxyethyl Starch Trial (CHEST)126 and Scandinavian Starch for Severe Sepsis/Septic Shock (6S) trial.127 Despite using modern tetrastarches with lower molecular size, lower concentration, and reduced molar substitution, CHEST reported an increase in RRT, and 6S reported an increase in both mortality and RRT in patients assigned to receive tetrastarch, as compared to patients assigned to receive crystalloid solutions. Both of these large studies, however, were conducted in critical care cohorts, and the generalizability of results to a perioperative population has been questioned. Small trials testing and reporting varying aspects of nephrotoxicity or nephroprotection associated with different types of colloids continue to emerge in the perioperative literature.81,83,84 However, the increased cost of synthetic starch solutions, together with a consistent failure to demonstrate a marked clinical outcome benefit from their administration, make it difficult to advocate for their continued perioperative use.

Oxidative Stress

Perioperative oxidative stress is independently associated with an increased risk of AKI.128 Antioxidant therapies tested include N-acetylcysteine and sodium bicarbonate.

To determine if the glutathione precursor and direct antioxidant N-acetylcysteine preserves renal function compared to placebo, 295 patients at high risk of kidney injury undergoing on-pump coronary bypass procedures were randomized to N-acetylcysteine vs. placebo. N-acetylcysteine did not affect renal dysfunction, defined as a 0.5 mg/dL or 25% serum creatinine increase from baseline within five days of surgery (RR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.72–1.46]; p=0.26).87 In a similar trial, 254 patients with CKD undergoing cardiac surgery were randomized to N-acetylcysteine or placebo, and 52% of patients receiving NAC vs. 40% of patients receiving placebo developed acute renal failure, defined as a 25% increase in serum creatinine from baseline (p=0.06).88 In 100 patients undergoing liver transplantation, randomization to perioperative NAC did not affect the rate of RIFLE-defined AKI (36% vs. 31% p=0.83).89 Taken as a whole, the evidence does not support NAC administration to reduce perioperative AKI.

Sodium bicarbonate is postulated to reduce oxidative stress in the nephron and thus renal injury by alkalinizing urine and slowing iron-dependent reactive oxygen species generation via the Haber-Weiss reaction129 or by directly scavenging reactive oxygen species from blood.130 These postulated mechanisms are supported by a meta-analysis indicating that administration of sodium bicarbonate decreases contrast-induced nephropathy.131 In a multicenter randomized trial, 350 patients undergoing cardiac surgery were randomized to receive a 24-hour infusion of sodium bicarbonate or 0.9% saline to determine if sodium bicarbonate reduces kidney injury or acute tubular damage quantified by measuring urinary concentrations of NGAL.6 Eighty three of the 174 patients receiving bicarbonate (47.7%) developed AKI, compared to 44 of the 176 patients receiving saline (25%)(OR 1.60 [95%CI, 1.04–2.45]; p=0.032). Postoperative NGAL concentrations also increased more in patients assigned to receive bicarbonate (p=0.011). The study was stopped early because interim analysis suggested lack of efficacy and possible harm among patients assigned bicarbonate. In a separate multicenter trial, McGuinness et al randomized 427 patients undergoing cardiac surgery to receive bicarbonate or sodium chloride infusions starting at induction of anesthesia and continued for 24-hours. Kidney injury was measured as a 25% or 0.5 mg/dL increase from baseline to peak within 5 postoperative days.90 One hundred of the 215 patients (47%) who received sodium bicarbonate and 93 of the 212 patients (44%) who received sodium chloride developed kidney injury (=0.58). In a similar study of 162 patients undergoing cardiac surgery and with risk factors for AKI, randomization to one hour of bicarbonate infusion vs. 0.9% saline at the start of surgery did not affect the rate of AKI (21 vs. 26%, =0.46) or postoperative serum cystatin C concentration (=0.85).91

In summary, perioperative trials to date do not support the use of NAC or sodium bicarbonate to decrease oxidative stress or AKI.

Remote Ischemic Preconditioning (RIPC)

RIPC is an adaptative response to brief ischemic episodes at a remote site that leads to some degree of protection for a target organ from a subsequent and more prolonged ischemia/reperfusion event.132 RIPC has been reported to attenuate ischemia-reperfusion injury in both animal (myocardium) and human (contralateral limb endothelial function) models.133 In the clinical context, a common technique uses a non-invasive blood pressure cuff to produce repeated cycles of short-term limb ischemia, with the aim of producing myocardial and renal protection. Recent perioperative clinical trials have produced conflicting results.

Zarbock et al applied three cycles of 5-minute arm ischemia with 5 minutes of reperfusion or sham to 240 patients at high risk for perioperative AKI undergoing cardiac surgery.72,73 RIPC treated patients had significantly less AKI within three postoperative days compared to sham patients (37.5% vs. 52.5%, p=0.02; RR, 0.71 [95% CI 0.54–0.95]). Assessment of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1) and biomarkers of renal stress (IGFBP7•TIMP-2) in the urine revealed that RIPC may elicit release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that induce renal stress and cell-cycle arrest and that these changes may lead to protection from subsequent renal injury. Indeed, elevated HMGB-1 and IGFBP7•TIMP-2 after RIPC correlated with reduced AKI, and RIPC reduced postoperative concentrations of IGFBP7•TIMP-2. In addition, 90-day follow up of this trial cohort demonstrated continued renal benefits among patients assigned to RIPC, including reduced MAKE90, reduced persistent renal dysfunction, and reduced RRT.77

These promising results were not replicated in two subsequent larger trials. Meybohm et al conducted a double-blind, multi-center randomized controlled trial of RIPC in 1403 patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.75 They employed four cycles of RIPC to an upper limb and found no difference in primary composite outcome of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or acute renal failure (defined as moderate to severe AKI) up to hospital discharge, nor any difference in moderate to severe AKI, as a secondary endpoint. Hausenloy et al also reported results of a double-blind, multi-center randomized trial of RIPC. They randomized 1612 high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass to four cycles of RIPC or sham and found no differences between RIPC and sham treatment groups in the primary cardiovascular outcome nor the secondary outcomes of AKI by postoperative day three, 24-hour plasma NGAL, or serum creatinine at 6-weeks or 1-year postoperatively.74 An important difference between the Zarbock study and the Meybohm and Hausenloy studies is that the Zarbock study mandated volatile anesthesia for maintenance of anesthesia while the Meybohm and Hausenloy studies were performed on patients receiving propofol anesthesia, and propofol attenuates the benefits of RIPC.

Additional clinical studies to better understand the impact of RIPC on perioperative AKI are currently underway (NCT02997748). RIPC has yet to translate into a routinely applicable clinical strategy for perioperative organ protection.

Summary

Perioperative clinical trials of AKI have largely focused on therapies that address factors known to be associated with AKI, such as hemodynamic markers of impaired perfusion and oxygen delivery, inflammation, oxidative damage, reperfusion injury, and acidosis. A large number of trials also compared novel anesthetic or surgical techniques to existing practices, reflecting continued evolution of perioperative patient management. Many of the trials targeting established or presumed mechanisms of AKI have failed. Nevertheless, several strategies can be reasonably advocated based on the available evidence, while acknowledging a degree of ongoing uncertainty (Table 2). In addition, novel therapeutics developed in preclinical models have either not advanced to clinical trials or failed to translate into effective patient management strategies. It should be noted that our study represents a subjective and qualitative evaluation of evidence identified through a systematic review process. As a result, the focus on and interpretation of specific studies discussed in the review will have been influenced by the authors’ own biases in interpretation. Future work will continue to develop our understanding of AKI pathophysiology, so that we may identify and clinically evaluate preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by the NIH (Bethesda, MD, USA) grants K23GM129662 to MGL and R01GM112871 to FTB.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

David R. McIlroy, Division of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology, Department of Anesthesiology; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA

Marcos G. Lopez, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Frederic T. Billings, IV, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Anesthesiology; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA; Division of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology, Department of Anesthesiology; Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

References

- 1.Meersch M, Schmidt C & Zarbock A. Perioperative Acute Kidney Injury: An Under-Recognized Problem. Anesthesia and analgesia 125, 1223–1232, doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002369 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle JF & Forni LG Acute kidney injury: short-term and long-term effects. Crit Care 20, 188, doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1353-y (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chawla LS, Eggers PW, Star RA & Kimmel PL Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. The New England journal of medicine 371, 58–66, doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billings FT t. Acute Kidney Injury following Cardiac Surgery: A Clinical Model. Nephron, 1–5, doi: 10.1159/000501559 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIlroy DR et al. Systematic review and consensus definitions for the Standardised Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine (StEP) initiative: renal endpoints. British journal of anaesthesia 121, 1013–1024, doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.08.010 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haase M. et al. Prophylactic perioperative sodium bicarbonate to prevent acute kidney injury following open heart surgery: a multicenter double-blinded randomized controlled trial. PLoS medicine 10, e1001426, doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001426 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase M. et al. Sodium bicarbonate to prevent increases in serum creatinine after cardiac surgery: a pilot double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Critical care medicine 37, 39–47 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKendry M. et al. Randomised controlled trial assessing the impact of a nurse delivered, flow monitored protocol for optimisation of circulatory status after cardiac surgery. BMJ 329, 258, doi: 10.1136/bmj.38156.767118.7C (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders G. et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial of acute normovolaemic haemodilution in major gastrointestinal surgery. British journal of anaesthesia 93, 775–781 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakeling HG et al. Intraoperative oesophageal Doppler guided fluid management shortens postoperative hospital stay after major bowel surgery. British journal of anaesthesia 95, 634–642, doi: 10.1093/bja/aei223 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donati A. et al. Goal-directed intraoperative therapy reduces morbidity and length of hospital stay in high-risk surgical patients. Chest 132, 1817–1824, doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0621 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benes J. et al. Intraoperative fluid optimization using stroke volume variation in high risk surgical patients: results of prospective randomized study. Crit Care 14, R118, doi: 10.1186/cc9070 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajjar LA et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 304, 1559–1567 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jhanji S. et al. Haemodynamic optimisation improves tissue microvascular flow and oxygenation after major surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Critical Care (London, England) 14, R151 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Linden P. et al. A double-blind, randomized, multicenter study of MP4OX for treatment of perioperative hypotension in patients undergoing primary hip arthroplasty under spinal anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia 112, 759–773 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Challand C. et al. Randomized controlled trial of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy in aerobically fit and unfit patients having major colorectal surgery. British journal of anaesthesia 108, 53–62, doi: 10.1093/bja/aer273 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearse RM et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 311, 2181–2190, doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5305 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy GJ et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery.[Erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2015 Jun 4;372(23):2274; PMID: 26039619]. New England Journal of Medicine 372, 997–1008 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid S. et al. Algorithm-guided goal-directed haemodynamic therapy does not improve renal function after major abdominal surgery compared to good standard clinical care: a prospective randomised trial. Crit Care 20, 50, doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1237-1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cholley B. et al. Effect of Levosimendan on Low Cardiac Output Syndrome in Patients With Low Ejection Fraction Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting With Cardiopulmonary Bypass: The LICORN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 318, 548–556, doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9973 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Futier E. et al. Effect of Individualized vs Standard Blood Pressure Management Strategies on Postoperative Organ Dysfunction Among High-Risk Patients Undergoing Major Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 318, 1346–1357, doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hajjar LA et al. Vasopressin versus Norepinephrine in Patients with Vasoplegic Shock after Cardiac Surgery: The VANCS Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 126, 85–93, doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001434 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landoni G. et al. Levosimendan for Hemodynamic Support after Cardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine 376, 2021–2031, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616325 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mazer CD et al. Restrictive or Liberal Red-Cell Transfusion for Cardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine 377, 2133–2144, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711818 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meersch M. et al. Prevention of cardiac surgery-associated AKI by implementing the KDIGO guidelines in high risk patients identified by biomarkers: the PrevAKI randomized controlled trial. Intensive care medicine 43, 1551–1561, doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4670-3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta RH et al. Levosimendan in Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine 376, 2032–2042, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616218 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gocze I. et al. Biomarker-guided Intervention to Prevent Acute Kidney Injury After Major Surgery: The Prospective Randomized BigpAK Study. Annals of surgery 267, 1013–1020, doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002485 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazer CD et al. Six-Month Outcomes after Restrictive or Liberal Transfusion for Cardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine 379, 1224–1233, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garg AX et al. Safety of a Restrictive versus Liberal Approach to Red Blood Cell Transfusion on the Outcome of AKI in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN 30, 1294–1304, doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019010004 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prinssen M. et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. The New England journal of medicine 351, 1607–1618, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042002 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shroyer AL et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. New England Journal of Medicine 361, 1827–1837 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown LC et al. Renal function and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA): the impact of different management strategies on long-term renal function in the UK EndoVascular Aneurysm Repair (EVAR) Trials. Annals of Surgery 251, 966–975 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith CR et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. The New England journal of medicine 364, 2187–2198, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Budera P. et al. Comparison of cardiac surgery with left atrial surgical ablation vs. cardiac surgery without atrial ablation in patients with coronary and/or valvular heart disease plus atrial fibrillation: final results of the PRAGUE-12 randomized multicentre study. European heart journal 33, 2644–2652 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lamy A. et al. Off-pump or on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 30 days. New England Journal of Medicine 366, 1489–1497 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu P. et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing infrahepatic inferior vena cava clamping with low central venous pressure in complex liver resections involving the Pringle manoeuvre. British Journal of Surgery 99, 781–788 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Bruin JL et al. Renal function 5 years after open and endovascular aortic aneurysm repair from a randomized trial. British Journal of Surgery 100, 1465–1470 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diegeler A. et al. Off-pump versus on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting in elderly patients. New England Journal of Medicine 368, 1189–1198 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamy A. et al. Effects of off-pump and on-pump coronary-artery bypass grafting at 1 year. New England Journal of Medicine 368, 1179–1188 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ranucci M. et al. A randomized controlled trial of preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump in coronary patients with poor left ventricular function undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Critical care medicine 41, 2476–2483 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garg AX et al. Kidney function after off-pump or on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a randomized clinical trial.[Erratum appears in JAMA. 2014 Jul 2;312(1):97]. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 311, 2191–2198 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thyregod HG et al. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis: 1-Year Results From the All-Comers NOTION Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 65, 2184–2194 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deeb GM et al. 3-Year Outcomes in High-Risk Patients Who Underwent Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 67, 2565–2574, doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.506 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haussig S. et al. Effect of a Cerebral Protection Device on Brain Lesions Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis: The CLEAN-TAVI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 316, 592–601, doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10302 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamy A. et al. Five-Year Outcomes after Off-Pump or On-Pump Coronary-Artery Bypass Grafting. The New England journal of medicine 375, 2359–2368, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601564 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leon MB et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. New England Journal of Medicine 374, 1609–1620 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mack MJ et al. Effect of Cerebral Embolic Protection Devices on CNS Infarction in Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 318, 536–547, doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9479 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reardon MJ et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. The New England journal of medicine 376, 1321–1331, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700456 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feldman TE et al. Effect of Mechanically Expanded vs Self-Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement on Mortality and Major Adverse Clinical Events in High-Risk Patients With Aortic Stenosis: The REPRISE III Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 319, 27–37, doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Popma JJ et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients. The New England journal of medicine 380, 1706–1715, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1816885 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nussmeier NA et al. Complications of the COX-2 inhibitors parecoxib and valdecoxib after cardiac surgery. New England Journal of Medicine 352, 1081–1091 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dieleman JM et al. Intraoperative high-dose dexamethasone for cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 308, 1761–1767 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Devereaux PJ et al. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. The New England journal of medicine 370, 1494–1503, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401105 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Devereaux PJ et al. Clonidine in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. The New England journal of medicine 370, 1504–1513, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401106 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg AX et al. Perioperative aspirin and clonidine and risk of acute kidney injury: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 312, 2254–2264 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacob KA et al. Intraoperative High-Dose Dexamethasone and Severe AKI after Cardiac Surgery. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 26, 2947–2951 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitlock RP et al. Methylprednisolone in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass (SIRS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 386, 1243–1253 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billings F. T. t. et al. High-Dose Perioperative Atorvastatin and Acute Kidney Injury Following Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 315, 877–888 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myles PS et al. Stopping vs. Continuing Aspirin before Coronary Artery Surgery. New England Journal of Medicine 374, 728–737 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park JH, Shim JK, Song JW, Soh S & Kwak YL Effect of atorvastatin on the incidence of acute kidney injury following valvular heart surgery: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive care medicine 42, 1398–1407, doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4358-8 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng Z. et al. Perioperative Rosuvastatin in Cardiac Surgery. New England Journal of Medicine 374, 1744–1753 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Hert SG et al. Choice of primary anesthetic regimen can influence intensive care unit length of stay after coronary surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology 101, 9–20 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rohm KD et al. Renal integrity in sevoflurane sedation in the intensive care unit with the anesthetic-conserving device: a comparison with intravenous propofol sedation. Anesthesia & Analgesia 108, 1848–1854 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song JC et al. A comparison of liver function after hepatectomy with inflow occlusion between sevoflurane and propofol anesthesia. Anesthesia & Analgesia 111, 1036–1041 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Svircevic V. et al. Thoracic epidural anesthesia for cardiac surgery: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology 114, 262–270 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Probst S, Cech C, Haentschel D, Scholz M & Ender J. A specialized post anaesthetic care unit improves fast-track management in cardiac surgery: a prospective randomized trial. Critical Care (London, England) 18, 468 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoo YC, Shim JK, Song Y, Yang SY & Kwak YL Anesthetics influence the incidence of acute kidney injury following valvular heart surgery. Kidney international 86, 414–422 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cho JS, Shim JK, Soh S, Kim MK & Kwak YL Perioperative dexmedetomidine reduces the incidence and severity of acute kidney injury following valvular heart surgery. Kidney international 89, 693–700, doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.306 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGuinness SP et al. A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Phase IIb Trial of Avoidance of Hyperoxemia during Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Anesthesiology 125, 465–473, doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001226 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smit B. et al. Moderate hyperoxic versus near-physiological oxygen targets during and after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Crit Care 20, 55, doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1240-6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Canty DJ et al. Pilot multi-centre randomised trial of the impact of pre-operative focused cardiac ultrasound on mortality and morbidity in patients having surgery for femoral neck fractures (ECHONOF-2 pilot). Anaesthesia 73, 428–437, doi: 10.1111/anae.14130 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]