Abstract

Heparin is one of the main pharmaceutical products manufactured from raw animal material. In order to describe the viral burden associated with this raw material, we performed high-throughput sequencing (HTS) on mucus samples destined for heparin manufacturing, which were collected from European pigs. We identified Circoviridae and Parvoviridae members as the most prevalent contaminating viruses, together with viruses from the Picornaviridae, Astroviridae, Reoviridae, Caliciviridae, Adenoviridae, Birnaviridae, and Anelloviridae families. Putative new viral species were also identified. The load of several known or novel small non-enveloped viruses, which are particularly difficult to inactivate or eliminate during heparin processing, was quantified by qPCR. Analysis of the combined HTS and specific qPCR results will influence the refining and validation of inactivation procedures, as well as aiding in risk analysis of viral heparin contamination.

Keywords: Virus, Heparin, Gut, Pig, Metagenomics, High-throughput sequencing

Abbreviations: Gc/mL, genome copies/mL; HTS, high-throughput sequencing; PAV A, porcine adenovirus A; PAV B, porcine adenovirus B; PBoV, porcine bocavirus; PCV, porcine circovirus; PCV1, porcine circovirus type 1; PCV2, porcine circovirus type 2; PPV1-6, porcine parvovirus 1 to 6; PPV7, putative porcine parvovirus 7; PRV-A, porcine group A rotavirus

1. Introduction

Heparin sodium is the purified sodium salt of heparin, a high molecular weight polysaccharide derived from porcine intestinal mucosa. Heparin sodium, or more frequently its derivative, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), is used as a class of anticoagulant medications [1]. Porcine heparin is prepared either from porcine intestinal mucosa or from whole minced gut. One pig is necessary to manufacture three doses of purified heparin or one dose of LMWH, and around 100 tons of heparin are manufactured every year [2]. The worldwide demand for both heparin sodium and LMWH has increased over the last few years, and currently, more than 20 million pigs worldwide are used for its manufacture each year. The raw material is likely to be rich in enteric viruses which are generally excreted at high titers, and which are often resistant to many physical and chemical treatments, therefore any recipient human patients could theoretically be exposed to porcine viruses. Moreover, increasing knowledge of the porcine enteric virome has so far uncovered greater viral diversity than previously thought [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [22]. The heparin manufacturing process involves numerous steps [1], each of which must undergo verification for their efficacy in either inactivating or removing viruses, according to current regulations. To help build contamination risk analyses, and to establish which viruses should be monitored, investigations must be undertaken to determine those viruses likely to contaminate the raw material, and their respective viral loads.

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) techniques efficiently detects viruses present in biological fluids (reviewed in Ref. [8]) and are increasingly being used in medical diagnosis [9], [10] or for screening biological materials [11], [12]. We have developed a pipeline, from sample preparation to bioinformatics [13], able to identify known, as well as new viruses [14], [15] and have recently demonstrated its use in evaluating the viral burden of fetal calf serum and trypsin used in cell culture [16]. Here we describe the analysis of viruses present upstream of the heparin manufacturing process. We show that a diverse range of both known and unknown viruses are present in this raw material, and discuss the impact of these results on establishing requirements for future viral validations.

2. Methods

2.1. Samples and preparation

A total of 10 mucus pool samples were collected in Europe, reflecting the diversity of the slaughterhouses utilized by a single manufacturer over several months. Each pool represented several hundreds of pigs and corresponded to the raw material used for pure heparin sodium manufacturing. 1 mL of each mucus sample was mixed with 9 mL of N-acetyl cysteine (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) at a concentration of 100 mg/mL, vortexed, centrifuged for 20 min at 4000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatants were filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and the virus particles of each pool were independently concentrated by ultracentrifugation for 2 h at 100,000 g through a cushion of 30% w/v sucrose. The pellet was resuspended in 150 μL of water and treated with a cocktail of nucleases adapted from metagenomic study of gut contents to digest non particle-protected nucleic acids (Turbo DNase (final concentration, 20 U/ml; Ambion) and RNase A (final concentration, 0.1 mg/ml; Fermentas) at 37 °C for 30 min) [17]. Enzymes were inactivated with a final concentration of 3 mM EDTA and heating at 10 min at 65 °C. The virus particles-associated genomes contained in 80 μL of each mucus pool sample were extracted with the Cador Qiagen Pathogen minikit (Hilden) and then amplified by the bacteriophage phi29 polymerase based multiple displacement amplification (MDA) assay using random primers. This technique allows DNA synthesis from DNA samples, and also from cDNA fragments from viral genomes previously colligated prior to Phi29 polymerase-MDA [18]. A mix with 4 μl of nucleic acids, 0.5 μl of primer (50 μM) and 0.5 μl of dNTPs (10 mM) was incubated at 75 °C for 5 min and cooled on ice for 5 min. Then, 5 μl of enzyme mix were added. This enzyme mix was composed of 2 μl of 10× RT Buffer for SSIII (Invitrogen Inc. Saint Aubin, France), 4 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 2 μl of 0.1 M DTT, 1 μl of 40 U/μl RNaseOUT (Invitrogen Inc., Saint Aubin, France), 1 μl of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Inc.). The final mix was incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, then at 45 °C for 90 min and finally at 95 °C for 5 min. The two following steps (ligation and MDA) were performed with the QuantiTect® Whole Transcriptome kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each of the ten samples provided concatemers of high molecular weight DNA at a concentration close to 1 μg/μL that were pooled before sequencing. Sample extraction and random amplification procedures were carefully performed to prevent cross-contamination, using the best precautionary PCR standards.

2.2. HTS and bioinformatic analysis

Reads were generated on an Illumina® HiSeq-2000 sequencer (DNAVision, Gosselies, Belgium) with a sequencing depth of 2.4 × 108 paired-end reads of 101 nt in length. Sequences were trimmed and filtered according to their quality score. Sequencing library preparation may introduce residual sample cross-contamination. After porcine genome sequence subtraction (susScr3, SGSC Sscrofa10.2 – NCBI project 13421, GCA_000003025.4, WGS AEMK01) with Cushaw2 and BlastN, reads were assembled in contigs using CLC Genomics Assembly Workbench (Cambridge, USA), and contigs and singletons were assigned a given taxonomy using the Blast algorithm. Criteria for taxonomic assignation have been described previously [16]. Sequences of the main contigs are available upon request.

2.3. PCR

Quantitative PCR was used to quantify virus loads for the known or candidate non-enveloped viruses identified in this study. SYBR green qPCR amplification was carried out in 20-μl reaction volumes that contained 2 μl of DNA, 1X Master Mix, and 500 nM each of the forward and reverse primers respectively (Table 2 ) (LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master, Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). qPCR analyses of all samples were performed in duplicate, and were conducted as indicated in Table 2 using the following primers: generic primers for known viruses (PCV1/2 and porcine bocavirus), or specifically designed primers based on a major contig, for unknown viruses (PPV7). Calibration curves were generated using a purified amplicon at known concentrations as control standards.

Table 2.

Conditions for real time PCR.

| Virus | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon size (nt) | Cycling conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circovirus 1 et 2 | Forward | TGGCCCGCAGTATTTTGATT | 72 | 45 cycles 95 °C: 10 s 58 °C: 5 s 72 °C: 10 s |

[34] |

| Reverse | CAGCTGGGACAGCAGTTGAG | ||||

| Bocavirus | Forward | GTACCGATCTATGATGTATCAC | 231 | 45 cycles 95 °C: 10 s 47 °C: 5 s 72 °C: 10 s |

[25] |

| Reverse | AAAGGACCCAARTAATTAT | ||||

| PPV7 | Forward | TGGTCGTGATGATGATGGG | 104 | 45 cycles 95 °C: 10 s 56 °C: 5 s 72 °C: 10 s |

|

| Reverse | CGCAGAGAAAGCCAAACAAG |

2.4. Role of the funding source

The study sponsors were not involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the viruses present in pig mucus

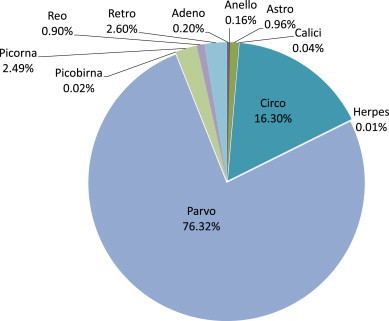

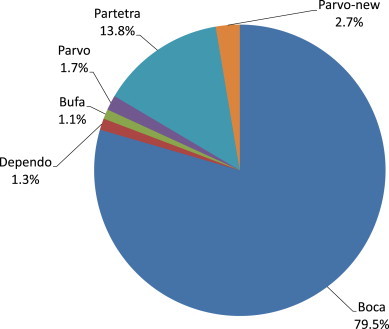

Fig. 1 depicts the proportion of reads corresponding to sequences that closely match known porcine viruses. The vast majority of viruses were found to be non-enveloped viruses, except for a few reads related to the Herpesviridae family, and reads from endogenous retroviruses that were likely to originate from contaminating porcine DNA. Members of the Parvoviridae family represented 76.3% of total viral reads, and within this group members of the bocavirus genus represented 79.5% of these Parvoviridae reads, followed by Partetravirus genus members (13.8%), as shown in Fig. 2 . Members of the Circoviridae family represented 16.3% of the total viral reads, which were mostly composed of PCV2 viruses (98.6%), while the remaining reads mapped to PCV1 and Po-Circolike virus 22 (data not shown) [6]. Sequences of the NIH-CQV virus, a known contaminant of Qiagen extraction columns [19], [20] were also identified and discarded. Other frequent reads (2.49%) were from Picornaviridae viruses, and more specifically from the newly described genus proposed as Pasivirus [3] (accounting for 78% of these reads, data not shown). Other viral families such as Picobirnaviridae, Reoviridae (mainly rotavirus A to C), Adenoviridae (mainly PAV A and B), Astroviridae, and Caliciviridae (mainly porcine sapovirus), were also represented, but at much lower frequencies.

Fig. 1.

Viral reads derived from pig mucus corresponding to known viruses Ratio of viral reads for each virus family to the total number of unique (non-duplicated) viral reads closest to a known virus species derived from the sample (456,437 reads).

Fig. 2.

Viral reads derived from pig mucus matching to known members of the Parvoviridae. Ratio of viral reads for each genus to the total number of unique (non-duplicated) viral reads closest to a known virus species from the Parvoviridae family (348,363 reads).

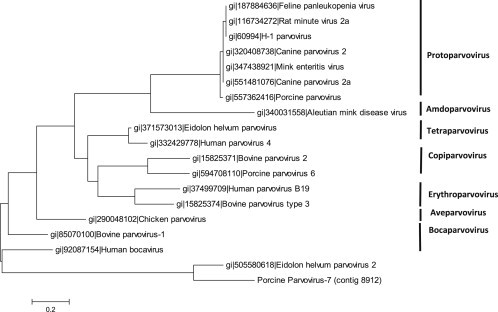

Putative new viral species were also identified. To address the study aim, we focused on those viruses that could be challenging to remove during the manufacturing process, because they belong to families known for either their physical resistance, their small size, or both (Table 1). Detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table S1. We identified potential novel viral species in the Astroviridae, Caliciviridae, Circoviridae, Parvoviridae, and Reoviridae families. The most frequent reads corresponded to members of the Parvoviridae family, and were distantly related (around 64% amino acid identity) to known parvoviruses. The most closely related was the Eidolon helvum parvovirus 2, an unclassified member of the partetravirus genus found in frugivore bats of Africa [21]. This suggests the presence of at least one new porcine parvovirus species that we have tentatively named porcine parvovirus 7. Fig. 3 shows that PPV7 clusters with Eidolon helvum parvovirus 2, which together might define a new genus in the Parvoviridae family.

Table 1.

Identification of putative new viral species within small resistant non-enveloped virus families.

| Family | Main species (# contigs) | Main GIa (# contigs with best hit for this GI) | # contigsb with best hit to this species | Number of reads in contigs | Average contig nucleotidic identity (%) | Average contig length | Average contig match length | Longest contig datac (length/match/nucleotidic identity) | Longest match datad (length/match/nucleotidic identity) | # singletonse | Average singleton nucleotidic identity (%) | Total number of readsf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astroviridae | Porcine astrovirus 5 (16) | 354682131 (9) | 34 | 308 | 82.78 | 178 | 105 | 338/95/92.63 | 291/240/78.33 | 24 | 82.13 | 332 |

| Caliciviridae | California sea lion sapovirus 1 (1) | 557357608 (1) | 3 | 30 | 79.42 | 247 | 139 | 350/206/84.95 | 350/206/84.95 | 5 | 83.09 | 35 |

| Circoviridae | Po-Circo-like virus 41 (40) | 354682166 (40) | 64 | 3047 | 49.42 | 291 | 201 | 944/297/39.39 | 516/543/34.81 | 22 | 82.91 | 3069 |

| Parvoviridae | Eidolon helvum parvovirus 2 (34) | 505580618 (32) | 182 | 51432 | 64.47 | 202 | 141 | 733/392/58.67 | 392/392/82.91 | 728 | 80.77 | 52160 |

| Reoviridae | Rotavirus F (46) | 388542459 (10) | 69 | 784 | 69.58 | 227 | 161 | 549/384/31.25 | 549/384/31.25 | 131 | 78.01 | 915 |

Unique identifiers for the sequence data in the NCBI database.

A sequence derived from a set of single overlapping reads.

Length of the longest contig, length of the match with the target sequence and % of identity of the match.

Length of the contig that includes the longest match, length of the match with the target sequence and % of identity of the match.

Reads that cannot be assembled in contigs.

Total number of reads singletons or assembled in contigs.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the putative new porcine parvovirus (PPV7) The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model [35]. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−1514.4280) is shown. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 19 partial amino acid sequences of the putative protein NS1. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 66 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA6 [36]. The tree is labeled according to the proposed new genus names within the Parvoviridae family [37].

We also identified new viruses related to the Circoviridae family, distant from both the enteric viruses previously described as Porcine Circovirus-like (Po-Circo-like 41 and 51) [6], as well as columbid and duck circoviruses (data not shown). Novel astroviruses and rotaviruses were also identified. In addition, we also identified sequences mapping to a virus of the Birnaviridae family, similar to that of the chicken infectious bursal disease, which might represent the first reported incidence of a birnavirus found in mammals or might derived from partially digested avian food.

3.2. Viral load of major non-enveloped viruses in pig mucus

To assess the frequency and load of non-enveloped viruses which corresponded to the highest viral read counts, we tested each of the ten mucus pools, using qPCR specifically targeted to the relevant PCV1-2 viruses, and the porcine bocavirus from the Parvoviridae family. In addition, to estimate the challenge an unknown virus might bring to the production process, we also tested for the newly discovered PPV7 (Table 3 ). We determined that all batches of mucus contained very high loads of non-enveloped viruses: the highest loads were recorded for PCV1/2 (7.6–8.7 log gc/mL), followed by Parvoviridae members (6.9–8.4 log gc/mL). On average, mucus batches contained 8.1 log gc/mL of PCV1/2, bocavirus, and PPV7.

Table 3.

qPCR analysis of different batches of mucus for different non-enveloped viruses.

| Mucus lot | PCV1-2 | Bocavirus | PPV7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.3a | 8.4 | 8.4 |

| 2 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| 3 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.2 |

| 4 | 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.3 |

| 5 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 8.2 |

| 6 | 8.4 | 8.2 | 8.2 |

| 7 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| 8 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.4 |

| 9 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 6.9 |

| 10 | 8.5 | 8.0 | Neg |

Log genome copies per mL mucus, average of two replicates.

4. Discussion

We describe here the viral burden of pig intestinal mucus, the most frequently used raw animal material for the manufacture of a biological product, heparin. To our knowledge, this is the first broad viral analysis of such material. We show here that numerous viral sequences are present in the raw pig intestinal mucus, as expected for samples directly derived from gut contents. As the material utilized for high-throughput sequencing were nuclease-treated pellets resulting from ultracentrifugation, it is likely that sequences obtained correspond to whole virus particles, even if we cannot totally exclude that non-encapsidated nucleic acids protected within aggregates might have also influenced results.

Total viral content was dominated by non-enveloped viruses, typical of enteric viruses. We identified members of the Circoviridae and Parvoviridae families as the major mucus-contaminating viruses. The fecal pig virome, which in theory should be similar to the mucosal virome, was examined recently via HTS and our findings were similar in relation to the main virus families identified. Nevertheless, the proportion of each virus family generally differed, which could perhaps be due to variation between animals, where studies were conducted on individual pigs from one or a limited number of herds [5], [6]. It should be emphasized that most of the identified viruses were not porcine pathogens. For example, whilst PCV2 (the main detected species) is responsible for the post-weaning multisystemic wasting syndrome [23], PCV1 seems to be non-pathogenic. Porcine bocaviruses are diverse and have not yet been associated with disease [24], [25]. These are interesting findings, as most testing guidelines for the viral safety of biological products are dominated by the search for porcine pathogens. This is evidently due to bias as veterinary virology is dominated by research on animal diseases. Indeed, most of the zoonotic viruses infecting humans are either weakly, or not at all pathogenic in their animal reservoir. Therefore we should remain cautious about predicting the impact of such “non-pathogenic” animal viruses on human health. Moreover, we mainly detected positive-ssRNA or -ssDNA viruses, which are known to harbor marked capabilities in adapting to new hosts following successful initial cross-transmission events. On the other hand, we did not detect viruses known to be transmissible to humans, such as influenza [26], HEV [27] and EMCV [28], while the zoonotic status of some of the identified viruses (rotavirus [29] and norovirus [30]) are still the subject of fierce debate.

The level of sensitivity of our pipeline is close to that of PCR for known viruses as shown previously for a depth of sequencing close to 8 million reads per sample [13] and confirmed recently for a higher depth of sequencing similar to that used in this study, which in addition allows for a better genome coverage [31]. So, it seems unlikely that a high load of a virus able to challenge the drastic manufacturing process of heparin could escape detection. The pipeline has also been shown to detect viruses very distant from known species (this paper and [3]), but it remains indeed possible that a virus very far from those already present in databases might escape such detection.

The number of NGS reads is not proportional to the relative abundance of viral genomes, as the different genome types (single/double stranded DNA/RNA) are amplified differently. Also, the coverage of the viral genomes is generally not uniform [13]. So, it is currently impossible to estimate virus loads from NGS results. Due to the study's objective and the resultant viral diversity, we decided to focus quantitative analysis on a subset of those viruses which may be especially resilient to removal or inactivation during the manufacturing process i.e. Circoviridae and Parvoviridae. Both are very resistant to physical and chemical inactivation, and in addition, are the smallest of vertebrate viruses (17–24 nm and 18–26 nm respectively), and thus are the most difficult to clear by nanofiltration. Among the Parvoviridae, we chose two species: porcine bocavirus, representing 79.5% of Parvoviridae reads, and the new PPV7 virus, to model unknown viruses which would not have been detected using current PCR methods. Circoviruses and the two parvoviruses were present in 9/10 batches (PPV7 was not detected in batch 10). Viral loads were high and remarkably similar between batches, which is probably a consequence of frequent shedding and the large size of the tested pools (several hundred pigs), which probably averages out viral loads. The ten mucus batches contained between 7.6 and 8.5 log gc/mL of several non-enveloped small DNA viruses, which represents severe challenges for downstream purification processes.

Animals are sourced worldwide for heparin purification, including animals from North America and China. Consequently, as these mucus samples were collected from European herds, results may not be representative of all mucus sources. Nevertheless, it is likely that certain resident viruses represent a viral profile characteristic of this animal species. This analysis did not take into account geographical sources of variation, which are further complicated by the multiplicity of pig strains. Neither did it examine the impact that any enteric viral diseases could have on viral excretion. Coronaviruses, such as the porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV), and rotaviruses (PRV-A), are major porcine viruses causing enteric disease [32], [33]. Even so, the Reoviridae members (including rotaviruses) were poorly represented in the viral count (0.9%), and no coronaviruses were identified. Inclusion of a herd with acute viral diarrhea would have most likely have modified the mucosal viral composition.

Our results should help to define guidelines for the appropriate validation of procedures for the inactivation of pertinent resistant viruses, like parvoviruses and circoviruses, the two main adventitious viruses revealed here. To validate these inactivation processes, Porcine parvovirus (PPV) or any other Parvoviridae member would represent a relevant reference virus. Use of circovirus would also aid in the validation of the more challenging nanofiltration steps. The choice of enveloped viruses classically used in the validation of manufacturing processes appears to be of lower interest compared to the risks of raw material contamination assessed here.

Evaluation of the probability of survival of viruses in the final product would necessitate to subtract the reduction factor of validated steps of the process from the load of viruses upstream of the process. This is outline the scope of the paper as this would necessitate to know not only the viral titers in the mucus (this study), but also the amount of mucus used for the manufacture of each dose, and the validated reduction factors of the manufacturing process.

Currently, mucus samples do not undergo viral testing prior to processing. In any case, the assays would have been uninformative, as all mucus samples contain viruses, and moreover, there are neither bio- nor molecular assays available for several virus types. Heparin safety thus relies on efficient inactivation and/or removal capabilities during processing. Using a combination of NGS analysis and quantitative PCR techniques, it is now feasible to characterize the viral burden of such raw materials. The resulting in-depth data of viral species and loads would then guide the selection of viruses used to validate inactivation processes, and could also be used to build risk analyses needed for the release of biological products on the market.

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from the BioSecure Foundation, Paris, Virus-Biol-HTS and the Labex IBEID. We thank Rachel Pert for the English correction of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.10.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Linhardt R.J., Gunay N.S. Production and chemical processing of low molecular weight heparins. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1999;25(Suppl. 3):5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H., Zhang Z., Linhardt R.J. Lessons learned from the contamination of heparin. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:313–321. doi: 10.1039/b819896a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sauvage V., Ar Gouilh M., Cheval J., Muth E., Pariente K., Burguiere A. A member of a new picornaviridae genus is shed in pig feces. J Virol. 2012;86:10036–10046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00046-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung A.K., Ng T.F., Lager K.M., Bayles D.O., Alt D.P., Delwart E.L. A divergent clade of circular single-stranded DNA viruses from pig feces. Arch Virol. 2013;158:2157–2162. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1701-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lager K.M., Ng T.F., Bayles D.O., Alt D.P., Delwart E.L., Cheung A.K. Diversity of viruses detected by deep sequencing in pigs from a common background. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2012;24:1177–1179. doi: 10.1177/1040638712463212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shan T., Li L., Simmonds P., Wang C., Moeser A., Delwart E. The fecal virome of pigs on a high-density farm. J Virol. 2011;85:11697–11708. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05217-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L., Kapoor A., Slikas B., Bamidele O.S., Wang C., Shaukat S. Multiple diverse circoviruses infect farm animals and are commonly found in human and chimpanzee feces. J Virol. 2010;84:1674–1682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mokili J.L., Rohwer F., Dutilh B.E. Metagenomics and future perspectives in virus discovery. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lecuit M., Eloit M. The diagnosis of infectious diseases by whole genome next generation sequencing: a new era is opening. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:25. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodemer C., Sauvage V., Mahlaoui N., Cheval J., Couderc T., Leclerc-Mercier S. Live rubella virus vaccine long-term persistence as an antigenic trigger of cutaneous granulomas in patients with primary immunodeficiency. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014 doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capobianchi M.R., Giombini E., Rozera G. Next-generation sequencing technology in clinical virology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:15–22. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClenahan S.D., Uhlenhaut C., Krause P.R. Optimization of virus detection in cells using massively parallel sequencing. Biologicals. 2014;42:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheval J., Sauvage V., Frangeul L., Dacheux L., Guigon G., Dumey N. Evaluation of high-throughput sequencing for identifying known and unknown viruses in biological samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3268–3275. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00850-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauvage V., Foulongne V., Cheval J., Ar Gouilh M., Pariente K., Dereure O. Human polyomavirus related to African green monkey lymphotropic polyomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1364–1370. doi: 10.3201/eid1708.110278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sauvage V., Cheval J., Foulongne V., Gouilh M.A., Pariente K., Manuguerra J.C. Identification of the first human gyrovirus, a virus related to chicken anemia virus. J Virol. 2011;85:7948–7950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00639-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gagnieur L, Cheval J, Gratigny M, Hébert C, Muth E, Dumarest M, et al. Unbiased analysis by high throughput sequencing of the viral diversity in fetal bovine serum and trypsin used in cell culture. Biologicals. 10.1016/j.biologicals.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Phan T.G., Kapusinszky B., Wang C., Rose R.K., Lipton H.L., Delwart E.L. The fecal viral Flora of Wild Rodents. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002218. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berthet N., Reinhardt A.K., Leclercq I., van Ooyen S., Batéjat C., Dickinson P. Phi29 polymerase based random amplification of viral RNA as an alternative to random RT-PCR. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naccache S.N., Greninger A.L., Lee D., Coffey L.L., Phan T., Rein-Weston A. The perils of pathogen discovery: origin of a novel parvovirus-like hybrid genome traced to nucleic acid extraction spin columns. J Virol. 2013;87:11966–11977. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02323-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smuts H., Kew M., Khan A., Korsman S. Novel hybrid parvovirus-like virus, NIH-CQV/PHV, contaminants in silica column-based nucleic acid extraction kits. J Virol. 2014;88:1398. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03206-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baker K.S., Leggett R.M., Bexfield N.H., Alston M., Daly G., Todd S. Metagenomic study of the viruses of African straw-coloured fruit bats: detection of a chiropteran poxvirus and isolation of a novel adenovirus. Virology. 2013;441:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheung A.K., Ng T.F.-F., Lager K.M., Alt D.P., Delwart E.L., Pogranichniy R.M. Unique circovirus-like genome detected in pig feces. Genome Announc. 2014:2. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00251-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allan G.M., McNeilly F., Kennedy S., Daft B., Clarke E.G., Ellis J.A. Isolation of porcine circovirus-like viruses from pigs with a wasting disease in the USA and Europe. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1998;10:3–10. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shan T., Lan D., Li L., Wang C., Cui L., Zhang W. Genomic characterization and high prevalence of bocaviruses in swine. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Y.-H., Xiao C.-T., Yin S.-H., Gerber P.F., Halbur P.G., Opriessnig T. High prevalence and genetic diversity of porcine bocaviruses in pigs in the USA, and identification of multiple novel porcine bocaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2014;95:453–465. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.057042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zell R., Scholtissek C., Ludwig S. Genetics, evolution, and the zoonotic capacity of European Swine influenza viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2013;370:29–55. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christou L., Kosmidou M. Hepatitis E virus in the Western world–a pork-related zoonosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:600–604. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rivera-Benitez J.F., Rosas-Estrada K., Pulido-Camarillo E., de la Peña-Moctezuma A., Castillo-Juárez H., Ramírez-Mendoza H. Serological survey of veterinarians to assess the zoonotic potential of three emerging swine diseases in Mexico. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014;61:131–137. doi: 10.1111/zph.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Midgley S.E., Bányai K., Buesa J., Halaihel N., Hjulsager C.K., Jakab F. Diversity and zoonotic potential of rotaviruses in swine and cattle across Europe. Vet Microbiol. 2012;156:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bank-Wolf B.R., König M., Thiel H.-J. Zoonotic aspects of infections with noroviruses and sapoviruses. Vet Microbiol. 2010;140:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabannes E., Hebert C., Eloit M. Whole genome- next generation sequencing as a virus safety test for biotechnological products. 2014. Proceedings from the 2013 PDA/FDA advanced technologies for virus detection Conference – Special Issue of the PDA Journal. [In Press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ben Salem A.N., Chupin Sergei A., Bjadovskaya Olga P., Andreeva Olga G., Mahjoub A., Prokhvatilova Larissa B. Multiplex nested RT-PCR for the detection of porcine enteric viruses. J Virol Methods. 2010;165:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halaihel N., Masía R.M., Fernández-Jiménez M., Ribes J.M., Montava R., De Blas I. Enteric calicivirus and rotavirus infections in domestic pigs. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:542–548. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puvanendiran S., Stone S., Yu W., Johnson C.R., Abrahante J., Jimenez L.G. Absence of porcine circovirus type 1 (PCV1) and high prevalence of PCV 2 exposure and infection in swine finisher herds. Virus Res. 2011;157:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cotmore S.F., Agbandje-McKenna M., Chiorini J.A., Mukha D.V., Pintel D.J., Qiu J. The family parvoviridae. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.