Abstract

Statement of problem.

Despite the high prevalence of posterior cracked teeth, questions remain regarding the best course of action for managing these teeth.

Purpose.

The purpose of this clinical study was to identify and quantify the characteristics of visible cracks in posterior teeth and their association with treatment recommendations among patients in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network.

Material and methods.

Network dentists enrolled patients with a single, vital posterior tooth with at least 1 observable external crack. Data were collected at the patient-, tooth- and crack-level, including the presence and type of pain and treatment recommendations for subject teeth. Frequencies according to treatment recommendation were obtained, and odds ratios (OR) comparing recommendations for the tooth to be restored versus monitored were calculated. Stepwise regressions were performed using generalized models to adjust for clustering; characteristics with P<.05 were retained.

Results.

A total of 209 dentists enrolled 2858 patients with a posterior tooth with at least 1 crack. Mean ±standard deviation patient age was 54 ±12 years; 1813 (63%) were female, 2394 (85%) were non-Hispanic white, 2213 (77%) had some dental insurance, and 2432 (86%) had some college education. Overall, 1297 (46%) teeth caused 1 or more of the following types of pain: 1055 sensitivity to cold, 459 biting, 367 spontaneous. A total of 1040 teeth were recommended for 1 or more treatments: restoration (1018; 98%), endodontics (n=29; 3%), endodontic treatment and restoration (20; 2%), extraction (n=2; 0.2%), and noninvasive treatment (for example, occlusal device, desensitizing (n=11; 1%). The presence of caries (OR=67.3), biting pain (OR=7.3), and evidence of a crack on radiographs (OR=5.0) were associated with over 5-fold odds of recommending restoration. Spontaneous pain was associated with nearly 3-fold odds; pain to cold, having dental insurance, a crack that was detectable with an explorer or blocked trans-illuminated light, or connected with a restoration were each weakly associated with increased odds of recommending a restoration (OR<2.0).

Conclusions.

Approximately one-third of cracked teeth were recommended for restoration. The presence of caries, biting pain, and evidence of a crack on a radiograph were strong predictors of recommending a restoration, although the last only accounted for a 3% absolute difference (4% recommended treatment versus 1% recommended monitoring).

INTRODUCTION

Teeth with cracks are a common occurrence in adults, with prevalence rates of up to 70%, depending on tooth type and location.1 The diagnosis and treatment of cracked teeth have been challenging for dentists and patients, and the outcomes can be consequential, with the need for a major restoration, root canal therapy, or extraction.2 As a result, finding the best treatment option for cracked teeth is a priority. Various procedures have been suggested either to aid in the diagnosis or treatment of a cracked tooth, including occlusal adjustment, sedative interim restorations, placement of orthodontic bands, interim crowns, direct or indirect composite restorations, complex and bonded amalgam restorations, and partial and complete indirect crowns.3–12

In a practice-based study in which 1777 dentists were presented with various clinical scenarios, the presence of a crack or fracture was the factor most likely to result in the dentist recommending a crown.11 Another study presented 95 dentists (generalists, prosthodontists, and endodontists) with 4 different clinical cracked tooth scenarios and asked what treatment they would recommend. Treatment suggestions were wide-ranging and were not related to the practitioners’ specialty. A variety of factors contribute to the decision to restore versus monitor a tooth, including caries, the quality of remaining tooth structure, presence of a visible fracture line, sealing the tooth against bacterial ingress, protecting cusps against flexure under function, presence of an existing restoration and whether or not the patient has dental insurance.12–21 Evidence-based guidelines are needed for the treatment of cracked teeth. The purpose of this clinical study was to contribute to this evidential foundation by identifying and quantifying characteristics at the patient-, tooth- and crack-level and their association with treating posterior teeth with visible cracks among patients enrolled in the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

A detailed report of the study procedures, including enrollment and data collection, has been provided in a previous publication.22 In brief, the study used a convenience sample of participants between 19 and 85 years old enrolled by dentists in the National Dental Practice-based Research Network.23 To be eligible, participants were required to have at least 1 single, vital posterior tooth with at least 1 observable external crack. Participating dentists were asked to select 1 of these teeth in each patient and to characterize this tooth for 20 eligible participants, or as many as they could enroll in 8 weeks, whichever came first. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the lead investigators (T.H., J.F.), as well as by the various IRBs that oversee the 6 regions of the network. Informed consent was obtained for all participants entered into the study. There were 2 phases to enrollment: a pilot phase with 183 patients from 12 practices from April through July 2014, and a main launch phase that occurred from October 2014 through April 2015. The study instruments were evaluated in the pilot phase to address understandability, coverage, and ease of form completion and were revised for full study implementation based on feedback from pilot practitioners.

Dentists and their designated practice personnel were trained in data collection using a training manual developed and approved by the study PIs. Data were collected at the patient-, tooth-, and crack-level, including presence and type of pain, as well as data on treatment recommendations for participant teeth. Data forms are publicly available at http://nationaldentalpbrn.org/study-results/cracked-tooth-registry.php. Confirmation of tooth vitality of enrolled teeth was with cold24 (for example, refrigerant, ice), although other methods were used such as air, air/water spray, or electric pulp testing. Spontaneous pain information was obtained by patient report, sensitivity to cold was ascertained using refrigerant, ice, or air/water spray, and pain upon biting was verified by having the patient occlude on a device or instrument placed on the occlusal surface of the cracked tooth. To help patients discriminate between pain (an increased response to the cold or bite assessment) and an ordinary response, dentists were asked to also perform these tests on an unaffected (for example, the contralateral) tooth. Practitioners indicated reason(s) they recommended the study teeth for treatment from a list of 9 options (with the instruction to check all that apply, plus the option to write in an additional reason). If a practitioner recommended a tooth for restoration, they were asked to specify restoration type (intracoronal, partial crown, or complete crown), placement technique (direct or indirect), and adhesive bonding (yes or no).

Frequencies according to treatment recommendation were obtained and odds ratios (ORs) calculated for recommendations of treatment versus monitoring. As the validity of a statistical test depends on independent observations and the model and the test must reflect the correlation structure of the data in order to yield valid estimates of variance and valid statistical tests, patients within a practice represent clusters that are often correlated to the outcome being studied.25 Clustering typically reduces precision of estimation, yielding lower statistical power and wider confidence intervals compared with studies of equal sample size but without clusters. In a univariable fashion, each patient-, tooth-, and crack-level characteristic was entered into a logistic regression model that used generalized estimating equations (GEE) adjusted for clustering of patients within the practice and implemented using PROC GENMOD in SAS with CORR=EXCH option. This approach specified a model in which observations on individual patients within practitioners are allowed to be correlated, while those from different practitioners are assumed to be independent. This approach removed variability caused by differences among practitioners from the tests for association between the predictor variables and the outcome variable, and so uses the appropriate estimate of standard error for the statistical tests.

To identify independent associations for recommending that a study tooth be restored versus monitored, all characteristics with P<.05 after adjusting only for clustering of patients within the practice were entered into a full model, followed by backwards elimination to remove all variables for which P was >= .05, using GEE to adjust for clustering. After fitting the final model, all interaction terms were tested for significance at the 5% level. To assess robustness of findings, regressions were repeated comparing all definitive treatment recommendations (extraction, endodontics, and restorations) to monitoring only. All odds ratios and P values were adjusted for clustering of patients treated by the same practitioner with GEE. All analyses were performed using statistical software (SAS v9.4; SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

A total of 2858 patients with a posterior cracked tooth were enrolled by 209 practitioners. The mean/median was 14.8/15 patients per practice and a range of 1 to 20. The distribution of the characteristics that study dentists took into consideration when deciding whether to restore versus monitor a cracked tooth are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of factors in dentists’ decision to restore or monitor cracked teeth (N=2836).

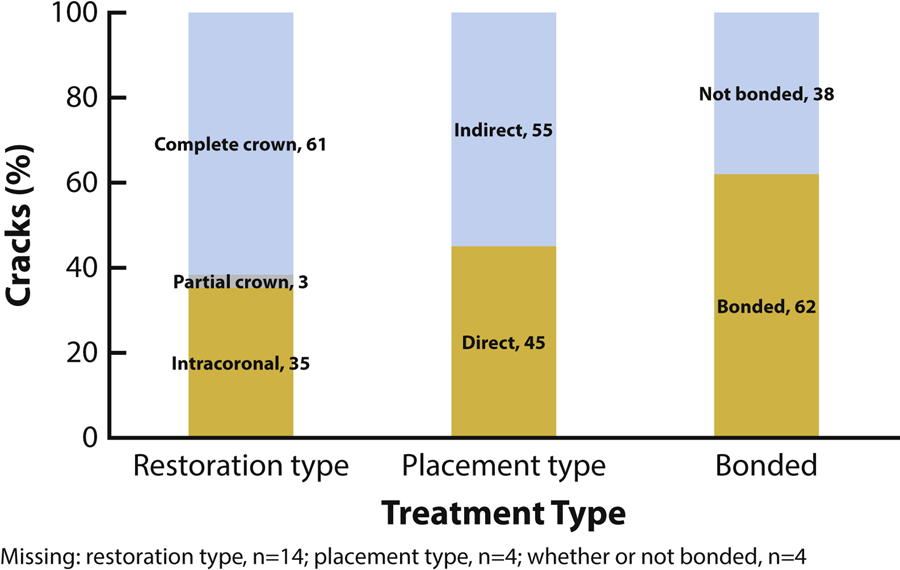

A total of 1040 teeth (36%) were recommended for the following treatments: restoration only (998; 96%), endodontic treatment only (9; 0.1%), endodontic treatment and restoration (20; 2%), extraction (2; 0.2%), or noninvasive treatment (for example, occlusal device, desensitizing; 11; 1%). The following is the disposition of the 1018 cracked teeth recommended for restoration: type of restoration: 357 (35%) intracoronal, 34 (3%) partial crown, 623 (61%) complete crown; type of placement: direct 452 (45%), indirect 562 (55%); bonded: yes 624 (62%), no 380 (38%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Restorative treatment recommendations by restoration type, placement type, bonding. (N=1018)

Virtually all of those teeth recommended for indirect placement were to receive complete crowns (N=534; 95%), and the majority of those teeth recommended for direct placement were to receive an intracoronal restoration (N=355; 79%). Similarly, the majority of restorations not recommended for bonding were complete crowns (N=315; 83%). Approximately equal numbers of intracoronal restorations and complete crowns were recommended as bonded restorations.

Practitioner-level characteristics

The mean age ±standard deviation (SD) of the practitioners was 53 ±10; the median age (interquartile range) was 56 (45 to 60) years, with a range from 27 to 73 years. Of the 209 dentists participating in the study, 153 (73%) practitioners were male, 173 (83%) were non-Hispanic white. Two practitioners were periodontists, the other 207 were general practitioners. Over half (N=118; 56%) were solo, private practitioners, with almost another third being either owners of non-solo private practices (N=46; 22%) or associates in private practices (N=17, 8%). Thirteen (6%) were in large group practices offering preferred care (HealthPartners or Permanente Dental Associates) and 6 (3%) were in academic centers.

Patient-level characteristics

The age range of patients was 19 to 85 years, with a mean age ±SD of 54 ±12, and a median age (interquartile range) of 55 (46 to 62) years. Of the 2858 patients enrolled in the study, 63% (N=1813, were female, 83% were non-Hispanic white (N=2394), 77% had some dental insurance (N=2213), and 85% had some college education (N=2432). Two-thirds of the patients (N=1900, 66%) reported clenching, grinding, or pressing their teeth together, and 2190 of 2690 main launch participants (81%) reported feeling at least some stress, with over one-third reporting feeling stress at least weekly (N=1048, 39%). Data on stress were not obtained in the pilot phase. A total of 1297 (45%) of the teeth were symptomatic. Pain was noted from cold stimuli (N=1055; 81%), biting (N=459; 35%); spontaneous pain was also reported (N=367; 28%); 409 (35%) had more than 1 type of symptom.

Age was inversely associated with a tooth being recommended for restoration (OR=0.86 per 10 years, P<.001). A patient who had dental insurance (OR=1.4, P<.001), cold pain (OR=2.8, P<.001), biting pain (OR=9.0, P<.001), and spontaneous pain (OR=5.6, P<.001) were likely to be recommended to receive a restoration rather than monitoring.

Tooth-level characteristics

Most cracked teeth were molars (N=2332; 82%), more than half of which were in the mandibular arch (N=1675, 59%). The vast majority of external cracks, N=2640 (92%), were on a tooth with a restoration: N=2041 (71%) of cracked teeth had 1 restoration, N=547 (19%) had 2 restorations and N=52 (2%) had 3 or 4 restorations. Slightly more than one-third (N=1018; 36%) of the teeth had 1 external crack, 759 (27%) had 2, 507 (18%) had 3, and 574 (20%) had 4 or more. Of the total, 638 (22%) had some root exposure, 676 (24%) presented with at least 1 wear facet through enamel, and 254 (9%) had a noncarious cervical lesion (NCCL). Only 53 (2%) had evidence of a crack on a radiograph. Of 302 (11%) teeth with caries present, only 6 (<1%) were on a tooth that practitioners recommended for monitoring.

The presence of caries was strongly associated with a tooth being recommended for restoration rather than monitoring (OR=54.8, P<.001). Evidence of a crack on a radiograph was also strongly associated with a restoration recommendation (OR=4.9, P<.001), while a crack on a molar (OR=1.6, P<.001), multiple external cracks (OR=1.3, P=.006), and the presence of a wear facet through the enamel (OR=1.4, P<.001) were each modestly associated with a recommendation for restoration. Cracked teeth with exposed roots were inversely associated (OR=0.8, P=.018) with a restoration recommendation. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Analysis of tooth-level characteristics according to treatment versus monitor recommendation at baseline

| Tooth-level characteristic1 | Monitor (N=1818) | Restore (N=1018) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Col3 % | N | Row4 % | |

| Molar | 1436 | 79% | 877 | 38% |

| Premolar | 382 | 21% | 141 | 27% |

| cluster adjusted OR5 | OR=1.6 | |||

| cluster adjusted P6 | P<.001 | |||

| 2 or more external cracks | 680 | 37% | 691 | 50% |

| 1 external crack | 1138 | 63% | 327 | 22% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.3 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P=.006 | |||

| Wear facet through enamel | 385 | 21% | 286 | 43% |

| No wear facet through enamel | 1433 | 79% | 732 | 34% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.4 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

| Exposed roots | 427 | 23% | 206 | 33% |

| No exposed roots | 1391 | 77% | 812 | 37% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=0.8 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P=.018 | |||

| Caries present | 6 | <1% | 295 | 98% |

| No caries present | 1812 | 100% | 723 | 29% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=54.8 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

| NCCL present | 169 | 9% | 83 | 33% |

| No NCCL present | 1649 | 91% | 935 | 36% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=.8 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P=.122 | |||

| Evidence of crack(s) on radiograph | 12 | 1% | 41 | 77% |

| No evidence of crack(s) on radiograph | 1806 | 99% | 977 | 35% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=4.9 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

NCCL: Noncarious cervical lesion

Column Ns not summing to column total N above due to missing data

Column percentages not summing to 100 due to rounding.

Percentage recommended for restoration within level of tooth-level characteristic: (# with recommend restore/(# recommend restore + # recommend monitor)

OR: Odds ratio adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using generalized estimating equations. Typically, cluster adjusted OR is similar to crude OR, for example, molar crude OR=(877)(382)/(1,436)(141)=1.6, same as cluster-adjusted OR. In contrast, for multiple cracks crude OR=(691)(1,138)/(680)(327)=3.5 while adjusted OR lower at 1.3, For caries, crude OR=(295)(1,812)/(6)(723)=123 with adjusted OR=54.8. Difference between crude OR and adjusted OR happens when patients of few practitioners different from patients of majority. Large difference for caries partly due to small number (6) of patients with caries monitored and not restored.

Significance of differences in proportions recommended to restore adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using generalized estimating equations.

Crack-level characteristics

Overall, study teeth exhibited the following crack-level characteristics: stained (N=2319; 81%), connected with a restoration (N=2095 73%), detectable with an explorer (N=1980; 69%), or blocked transilluminated light (N=1862; 65%). Fewer teeth presented with the crack extending to the root (N=297; 10%) or connected with another crack (N=121; 4%). Tooth surfaces with cracks varied over a narrow range, from 44% (N=1267) involving the occlusal surface to 51% (N=1463) involving the lingual surface; 1028 (36%) had a crack that involved 2 or more surfaces.

Having a crack that stained (OR=1.3, P=.006), that was detectable with an explorer (OR=1.8, P<.001), that blocked transilluminated light (OR=1.6, P<.001), that connected with a restoration (OR=1.4, P<.001), or that connected with another crack (OR=1.5, P=.023) were each modestly associated with an increased likelihood of the tooth being recommended for restoration. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Analysis of crack-level characteristics according to treatment versus monitor recommendation at baseline

| Crack-level characteristics | Monitor (N=1818) | Restore (N=1018) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Col%2 | N | Row%3 | |

| At least 1 crack stained | 1464 | 81 | 843 | 37% |

| No cracks were stained | 354 | 19 | 175 | 33% |

| cluster adjusted OR4 | OR=1.3 | |||

| cluster adjusted P5 | P=.006 | |||

| At least 1 crack detectable with an explorer | 1192 | 66 | 773 | 39% |

| No cracks detectable with an explorer | 626 | 34 | 245 | 28% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.8 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

| At least 1 crack blocked transilluminated light | 1126 | 62 | 726 | 39% |

| No cracks blocked transilluminated light | 692 | 38 | 292 | 30% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.6 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

| At least 1 crack connected with a restoration | 1285 | 71 | 794 | 38% |

| No cracks connected with a restoration | 533 | 29 | 224 | 30% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.4 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P<.001 | |||

| At least 1 crack connected with another crack | 106 | 6 | 97 | 48% |

| No cracks connected with another crack | 1712 | 94 | 921 | 35% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.5 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P=.023 | |||

| At least 1 crack extended to root | 308 | 17 | 219 | 42% |

| No cracks extended to root | 1510 | 83 | 799 | 35% |

| cluster adjusted OR | OR=1.0 | |||

| cluster adjusted P | P=.771 | |||

Column Ns not summing to column total N above due to missing data

Column percentages not summing to 100 due to rounding.

Percentage recommended for restoration within level of crack-level characteristic: (# with recommend restore/(# recommend restore + # recommend monitor)

OR: Odds ratio adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using generalized estimating equations.

Significance of differences in proportions recommended to restore adjusted only for clustering of patients within practitioner using generalized estimating equations.

Independent associations

All possible 2-way interactions were evaluated and none were found significant, indicating that an additive model is sufficient. The independent associations with a tooth being recommended for restoration versus monitoring in the final models are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Independent associations with cracked tooth being recommended for restoration versus monitoring1

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caries present | 67.9 | 37.6 to 122.6 | <.001 |

| Biting pain | 7.3 | 5.2 to 10.2 | <.001 |

| Evidence on radiograph | 4.8 | 2.6 to 8.8 | <.001 |

| Spontaneous pain | 2.9 | 2.0 to 4.0 | <.001 |

| Cold pain | 1.7 | 1.4 to 2.2 | <.001 |

| Dental insurance | 1.3 | 1.1 to 1.6 | .006 |

| Has a crack that: | |||

| Is detectable with explorer | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.0 | <.001 |

| Blocks trans-illuminated light | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.8 | .019 |

| Connects with restoration | 1.4 | 1.1 to 1.8 | .005 |

| Horizontal direction | 1.3 | 1.0 to 1.6 | .024 |

Teeth recommended for nonsurgical treatments (n=11), endodontics only (n=9) or extraction (n=2) are excluded

From generalize estimating equations adjusting for clustering within practice using stepwise regression, retaining if P<.05

The presence of caries (OR=67.3; P<.001), biting pain (OR=7.3; P<.001), and evidence of a crack on radiographs (OR=4.8; P<.001) were each strongly associated with recommending restoration. Spontaneous pain was associated with a nearly 3-fold increase in the odds of the tooth being recommended for treatment (OR=2.9; P<.001). Pain to cold (OR=1.7; P<.001), having a crack that was detectable with an explorer (OR= 1.6; P<.001), that blocked transilluminated light (OR= 1.4; P=.019), that connected with a restoration (OR=1.4; P=.005),and that extended in a horizontal direction (OR=1.3; P=.024) or a patient with dental insurance (OR=1.3; P=.006) were each weakly associated with an increased odds of a recommendation for restoration (OR<2.0).

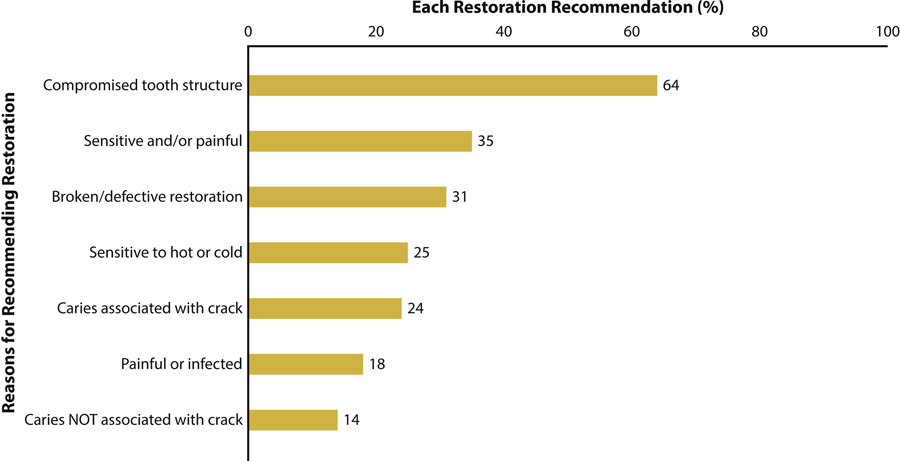

Analysis including all invasive treatment recommendations, namely, extraction, endodontic treatment, and restoration, compared with monitoring did not differ from the final model presented in Table 3 comparing restoration to monitoring excluding extraction and endodontic treatment. Numbers were insufficient to analyze extraction (n=2) separately. When modeling endodontic treatment either with or without restoration, only spontaneous pain (OR=13.0, 95% CI: 4.2 to 40.5, P<.001), biting pain (OR=7.0, 95% CI: 2.8 to 17.6, P=.001), and cold pain (OR=5.5, 95% CI: 1.99–16.0, P=.006) were independently significantly associated with increased odds of recommending restoration. The most common reason noted for recommending restoration was compromised tooth structure (64%), followed by painful or sensitive teeth (35%), broken or defective restorations (31%), caries associated with a crack (24%), and caries not associated with a crack (14%). (Fig. 3)

Figure 3:

Reasons for recommendation of restorative treatment (N=1018).

DISCUSSION

This study showed that if active intervention for a posterior cracked tooth (versus monitoring) is chosen, almost always (98%), the management of choice is restorative treatment. Several factors go into the decision to restore versus monitor a cracked tooth. In this study, those that were most important in deciding to restore a cracked tooth were the presence of caries, pain, or radiographic evidence of a crack. Previous studies have reported a significant correlation between caries and radiographic evidence of a crack and pain in cracked teeth.12,13 A strong correlation was found between radiographic evidence of a crack and the practitioner’s decision to restore the tooth (OR=4.8), although the occurrence of radiographic evidence of a crack was low and the risk difference was only 3%. However, when present, an evident crack on a radiograph strongly correlated with pain, and often resulted in a recommendation from the practitioner to restore the tooth. Pain would dictate that a practitioner take definitive action to relieve discomfort. Likewise, caries is the most prevalent disease in both children and adults14 and as such mandates that therapy be instituted to address it. When caries was detected in conjunction with a cracked tooth, the practitioners in this study typically and predictably selected restorative treatment.

Other factors were more equivocal in their impact on a dentist’s decision to restore or monitor a cracked tooth, with similar numbers of dentists weighing factors such as the crack being detectable with an explorer, blocking transilluminated light, connecting with a restoration, as well as whether the patient had dental insurance as justification for both restoring and monitoring a cracked tooth. This confirms previous data that there is a low level of concurrence among dentists regarding the best way to manage a cracked tooth. A survey of 959 dentists asking them to rate the importance of 8 factors in cusp fracture found that, with the exception of dentinal support, no other factor was rated as very important by a majority of respondents, and only 1 factor (wear facets) was rated as important by more than one-third or those participating.15 However, our study also agreed with the survey regarding the importance of dentists’ assessment of the quality of remaining tooth structure. The most common rationale for recommending restorative treatment was the dentist’s judgement that tooth structure was compromised. This was cited almost twice as often as the next most common reason, a sensitive or painful tooth (64% versus 35%). Bader et al16 determined in a case control study that the 2 leading risk indicators for cusp fracture were the presence of a fracture line and an increase in the proportional volume of the natural tooth crown replaced with a restoration, both of which could be considered as contributing to compromising the integrity of the tooth.

When the decision was made to restore a cracked tooth, a most of the time (61%) the restoration of choice was a complete crown. A previous National Dental PBRN study found that the most common reason for treatment planning a crown was a tooth with a crack or fracture.11 Many treatments have been suggested for cracked teeth, ranging from short-term treatment directed at pain relief and aiding in diagnosis such as occlusal adjustment, sedative restoration, placement of an orthodontic band or interim crown,6–9 or a direct composite onlay splint,3 to definitive restorations including direct resin composite,6 indirect resin composites,4 and crowns.5 The clear preference found in this study was a crown. The primary rationales for restorative treatment for a cracked tooth are biological, that is sealing an avenue of bacterial contamination and toxic element ingress,4,7,8,17 and mechanical, that is splinting the fractured elements of the tooth to prevent tooth flexure causing pain and allowing crack progression.7,18 A complete crown accomplishes both of these functions.

Although associated with lesser odds ratios, several factors were found to be associated with a recommendation for restoring a cracked tooth, including having a crack that was detectable with an explorer, connected with a restoration, or blocked transilluminated light and a patient with dental insurance. A crack that is detectable with an explorer may be considered to represent a more definitive break in tooth structure and is potentially more ominous in terms of adverse events and therefore recommended for restorative treatment, particularly when associated with an adjacent restoration.19 A recent study20 reported that an external crack that connected with a restoration was more likely to have an internal crack in that tooth. Although supported by minimal evidence, the blocking of transilluminated light through a tooth is often recommended as a method of determining that a crack penetrates to dentin.2 Cracks that penetrate to dentin are suggestive of more extensive damage that would prompt a clinician to plan treatment to protect against more unfavorable outcomes, such as tooth fracture or a crack impinging on the pulp. A review found that individuals with dental insurance were more likely to use dental services than the uninsured; it is therefore understandable that this would be a factor in recommending treatment for cracked teeth.21

This study has several limitations. For practical reasons, the study population was not randomly selected. This allowed participating practitioners to select patients who both met the inclusion criteria and were most likely to return for recall visits. Such nonrandom selection could introduce bias, for example, if study patients are not representative of individuals who do not enter the dental care system. However, the long-term goal of the study is to develop guidelines for those dentists and patients who do participate in regular dental care. Another potential weakness was the subjective nature of specific measures used in the study. Although all participating personnel underwent training prior to participating, the fact that some of the assessments do not lend themselves to purely objective measurement could allow for variation in recorded data among the participants. Several clinical measures were used, and these could have been subject to errors in classification. However, misclassifications were probably random, and therefore associations reported are likely underestimated.

The study strengths include a high number of participants from a large variety of dental practices across the U.S. These practices collected a large amount of data in a systematic, controlled manner. Importantly, these patients will be followed for several years, hopefully allowing the assessment of the effectiveness of various management alternatives for the treatment of cracked teeth.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the findings of this clinical study, the following conclusions were drawn:

Caries and pain are most likely to result in practitioners recommending treatment of a cracked tooth.

Most of the time, the treatment of choice for a cracked tooth is placement of a restoration, and the restoration of choice is a complete crown.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS.

Various posterior tooth characteristics affect the clinician’s decision to monitor versus treat a cracked tooth. When the decision is made to treat the tooth, most commonly because of the practitioner’s concern about the integrity of the tooth or because the patient experienced pain, dentists and patients will usually opt for restorative treatment. The restorative treatment of choice for posterior cracked teeth is a complete crown.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the network’s regional coordinators who worked with network practitioners to conduct the study. Midwest region: Sarah Verville Basile, RDH, MPH, Christopher Enstad, BS; Western region: Camille Baltuck, RDH, BS, Lisa Waiwaiole, MS, Natalia Tommasi, MA, LPC; Northeast region: Patricia Ragusa, BA; South Atlantic region: Deborah McEdward, RDH, BS, CCRP, Brenda Thacker, AS, RDH, CCRP; South Central region: Claudia Carcelén, MPH, Shermetria Massengale, MPH, CHES, Ellen Sowell, BA; Southwest region: Stephanie Reyes, BA, Meredith Buchberg, MPH, Colleen Stewart, MA. The authors are also grateful to the 12 network practitioners who participated in this study as pilot study practitioners. Midwest: David Louis, DDS, Timothy Langguth, DDS; Western: William Reed Lytle, DDS, Don Marshall, DDS; South Atlantic: Stanley Asensio, DMD, Solomon Brotman, DDS; South Central Region: Jocelyn McClelland, DMD, James L. Sanderson Jr, DMD; Southwest: Robbie Henwood, DDS, PhD, Michael Bates, DDS; Northeast: Julie Ann Barna, DMD, MAGD; Sidney Chonowski, DMD, FAGD.

Supported by NIDCR, Grant U19-DE-22516.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hilton T, Mancl L, Coley Y, Baltuck C, Ferracane J, Peterson J, NW PRECEDENT. Initial treatment recommendations for cracked teeth in Northwest PRECEDENT. J Dent Res 91(A) 2011;abst 2387. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubisich E, Hilton T, Ferracane J. Cracked teeth: a review of the literature. J Esthet Restor Dent 2010;22;158–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerji S, Mehta S, Kamran T, Kalakonda M, Millar B. A multi-centred clinical audit to describe the efficacy of direct supra-coronal splinting – A minimally invasive approach to the management of cracked tooth syndrome. J Dent 2014;42:862–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Signore A, Benedicenti S, Covani U, Ravera G. A 4- to 6-year retrospective clinical study of cracked teeth restored with bonded indirect resin composite inlays. Int J Prosthodont 2007;20:609–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krell K, Rivera E. A six-year evaluation of cracked teeth diagnosed with reversible pulpitis: treatment and prognosis. J Endod 2007;33:1405–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Opdam N, Roeters J, Loomans B, Bronkhorst M. Seven-year clinical evaluation of painful cracked teeth restored with a direct composite restoration. J Endod 2008;34:808–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox K, Youngson C. Diagnosis and treatment of the cracked tooth. Prim Dent Care 1997;4:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbot P, Leow N. Predictable management of cracked teeth with reversible pulpitis. Aust Dent J 2009;54:306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banerji S, Mehta S, Millar B. Cracked tooth syndrome. Part 2: restorative options for the management of cracked tooth syndrome. Br Dent J 2010;208:503–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, Kim S, Cho S, Lee G, Yang S. Different treatment protocols for different pulpal and periapical diagnoses of 72 cracked teeth. J. Endod 2013;39:449–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCracken M, Louis D, Litaker M, Minye H, Mungia R, Gordan V, et al. Treatment recommendations for single-unit crowns. Findings from the national dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc 2016;147:882–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkhalifah S, Alkandari H, Sharma P, Moule A. Treatment of cracked teeth. J Endod 2017;43:1579–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gordan VV, Huff KD, Barna J, et al. Associates of types of pain with crack-level, tooth-level, and patient-level characteristics in posterior teeth with visible cracks: Findings from the National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. J Dent 2018;70:67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIDCR. Dental Caries. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/dental-caries. Accessed 7 May 2018.

- 15.Bader J, Shugars D, Roberson T. Using crowns to prevent tooth fracture. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996;24:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bader J, Shugars D, Martin J. Risk indicators for posterior tooth fracture. J Am Dent Assoc 2004;135:883–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahler B, Moule A, Stenzel D. Bacterial contamination of cracks in symptomatic vital teeth. Aust Endod J 2000;26:115–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seo D, Yi Y, Shin S, Park J. Analysis of factors associated with cracked teeth. J Endod 2012;38:288–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark D, Sheets C, Paquette J. Definitive diagnosis of early enamel and dentin cracks based on microscopic evaluation. J Esthet Restor Dent 2003;15:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferracane J, Funkhouser E, Hilton T, Gordan V, Graves C, Giese K, et al. Observable Characteristics Coincident with Internal Cracks in Teeth: Findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. 2018: in press, J Am Dent Assoc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Eklund S The impact of insurance on oral health. J Am Coll Dent 2001;68:8–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilton TJ, Funkhouser E, Ferracane JL, Gilbert GH, Baltuck C, Benjamin P, et al. Correlation between symptoms and external cracked tooth characteristics: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc 2017;148:246–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, Fellows JL, Gordan VV, Makhija SK, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Dent 2013;41:1051–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pigg M, Nixdorf D, Nguyen R, Law A. Validity of preoperative clinical findings to identify dental pulp status: a National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Study. J Endod 2016;42:935–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Litaker M, Gordan V, Rindal D, Fellows J, Gilbert G, National Dental PBRN Collaborative Group. Cluster Effects in a National Dental PBRN Restorative Study. J Dent Res 2013;92:782–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]