Abstract

A single chain fragment variable (scFv) antibody gene was isolated from hybridoma cell line secreting monoclonal antibody (MAb) 20E9 that recognises bluetongue virus (BTV) VP7. DNA fragments encoding variable regions of heavy and light chains were amplified by RT-PCR and library of scFv was constructed in phage vector. Two scFv clones that were selected showed specific reactivity with conformational epitope VP7. The N-terminal 22 amino acid residues of 20E9 light chain were identical to that deduced from scFv DNA sequence. An in-frame TAG stop codon was found in the coding sequence and its potential role in regulating the expression and stability of scFv in phage is discussed.

Keywords: ScFv, Filamentous phage, Coat protein, Bluetongue virus

Antibody engineering technology is a new area in the field of molecular immunology for production of large quantities of recombinant antibodies in bacteria and plants. They would be useful reagents for human and veterinary medicine, as well as agricultural industries for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of viral diseases.

Single chain fragment variable (scFv) antibodies are composed of variable heavy (VH) and variable light (VL) chains of antibody molecules connected by genetically encoded peptide linker (Bird et al., 1988, Huston et al., 1988). They are presented as fusion proteins at the tip of the minor coat protein of filamentous phages. These are the smallest units of soluble antibody produced in Escherichia coli and yet retain their function (McCafferty et al., 1990, Burton and Barbas, 1994, Winter et al., 1994). In the last 5 years, scFv have been made against animal, human and plant viruses for diagnosis and therapy. They include influenza viruses (Patterson et al., 1999), coronaviruses (Lamarre et al., 1997), hepatitis viruses (Chan et al., 1996, Yamamoto et al., 1999), HIV (Lilley et al., 1994), rabies virus (Muller et al., 1997) and also plant viruses (Tavladoraki et al., 1993, Franconi et al., 1999).

The orbivirus genus in the family Reoviridae contains three important viruses that cause animal diseases, bluetongue in sheep, African horse sickness and epizootic haemorrhagic disease in deer (Foster et al., 1980). They have ten double-stranded RNA segments encapsidated by two layers of proteins. The inner core consists of two major proteins, VP3 and VP7, and three minor proteins, VP1, VP4 and VP6. The VP7 is group-reactive antigen, hence it is used for BTV antibody detection (Huismans and Erasmus, 1981). A number of VP7-specific MAbs have been produced which recognise both linear and conformational epitopes. The MAb 20E9, which recognises conformational epitope (present on the virus surface) is used for BTV diagnosis (Lunt et al., 1988, Eaton et al., 1991). This study describes cloning, selection and characterisation of scFv fragments.

The PCR amplified coding regions of VH and VL chains from MAb20E9 were linked together by a flexible linker and cloned into vector pCANTAB5 at Sfi I and Not I sites. The ligation product was electroporated into TG1 cells (E. coli TG1 strain (supEhsdΔ5thiΔ(lac-proAB) F′ [traD36proAB+lacIqlacZΔM15], which neither modifies nor restricts transfected DNA (Maniatis et al., 1982) and grown overnight on LB plates with 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 2% glucose. Rescued recombinant phages were selected on antigens (either CLP or recombinant VP7) (Martyn et al., 1990, Zheng et al., 1999). After the third round of selection, 24 phages were tested in an ELISA and all the 24 clones reacted with anti-M13 antibody with mean OD450 2.78 (SD±0.02). However, only 2 of the 24 clones (4 and 5) reacted with BTV CLP and none reacted with BSA which served as a negative control.

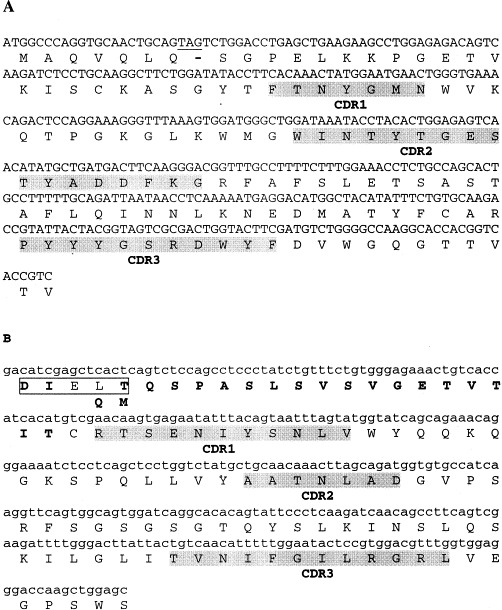

The scFv DNA inserts were sequenced using the primers fd-SEQ1 (5′-GAATTTTCTGTATGAGG-3′) and Rev (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′). The nucleotide sequences of VH and VL fragments have been deposited in the genBank (accession numbers, U89324 for VH and U89325 for VL). Nucleotide sequence results revealed that clones 4 and 5 have the same inserts. The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of VH and VL regions are shown in Fig. 1 . Both regions show homology with published sequences of mouse antibody genes and contain complementarity-determining regions (CDR). Nucleotide sequences revealed TAG stop codon in the VH coding sequence. From amino acid sequence determination, the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the light chain protein was found to be similar to deduced amino acid sequence from VL chain DNA fragment (Fig. 1). The N-terminus of heavy chain appeared to be blocked and no sequence was obtained.

Fig. 1.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the variable regions of heavy (A) and light chains (B) of scFv (from recombinant phage clone 4). For the light chain, primer-coded amino acid residues at the N-terminus were boxed, and the amino acid sequence determined by direct protein sequencing is given in boldface. The two residues given below the primer-coded sequence represent the primer-introduced difference between the original MAb 20E9 protein sequence and the deduced amino acid sequence of the cloned scFv. Residues corresponding to the complementarity-determining (CDR) regions are shaded and the in-frame TAG stop codon in the VH coding region is underlined. The 20E9 antibody gene fragments were assembled from about 106 hybridoma cells following manufacturer's instructions (Pharmacia, Uppsala).

In addition to CLP and BTV1 antigens, a group of non-related proteins were tested to validate the specificity of scFv. As shown in Table 1 , scFv reacted with CLP as expected. However, the reactivity was low with untreated BTV1 virus (OD450 in the range of 0.18–0.13) but this was significantly enhanced when the virus was treated with 1% SDS (OD450 increased to 0.88). There was no significant reactivity with any of the unrelated proteins. The specificity of the scFv was confirmed by competition ELISA. The scFv antibody binding was significantly inhibited (59%) by MAb 20E9 and there was no inhibition in the absence of MAb 20E9.

Table 1.

Binding of phage antibody to different proteinsa

| Antigen | OD450 |

|---|---|

| BSA | 0.08 |

| Lysozyme | 0.07 |

| VLP | 0.07 |

| CLP | 1.43 |

| BTV1 | 0.18 |

| BTV1(1%SDS treated) | 0.88 |

| Sf9 lysate | 0.06 |

Numbers indicate average OD450 readings of phage antibody binding to antigens in ELISA.

Genetically engineered antibodies have advantages over conventional antibodies. They could be produced in large quantities in bacteria with good quality control. They can also be engineered by affinity maturation and linked genetically to other protein molecules such as reporter enzymes or toxins for their use in diagnosis and treatment.

The scFv antibody showed similar binding specificity to its parental antibody when tested against VP7 and the binding was inhibited by MAb 20E9 indicating that the scFv still recognise the conformational epitope. It is also interesting to note that the reactivity of phage antibody was much stronger with SDS-treated BTV1 virus than the untreated virus. This is most likely due to “unmasking” of the 20E9 epitope by SDS treatment. Although it is known that the MAb 20E9 can access epitope in native virus (Eaton et al., 1991), exposure of the binding site is limited because VP7 is located beneath the outer capsid. After SDS treatment, the outer capsid may be partially damaged thus exposing the epitope binding site to scFv.

Nucleotide sequencing of both VH and VL revealed typical sequence features of mouse antibody molecules. Comparison of deduced scFv amino acid sequences with the corresponding N-terminal amino acids of 20E9 light chain confirmed its similarity with native MAb. The fact that the functional scFv was expressed indicated that host cell TG1 (which carries a suppresser gene and supports the growth of vectors with amber mutations) was able to read through stop codon found in the VH coding sequence (Maniatis et al., 1982). In-frame stop codons usually result in disruption of gene expression in other systems. However, in phage display system, detection limit is lower and low level of read-through activity can be detected. Suppression of TAG stop codon has been utilised in the design of many phage vectors, including pCANTAB5 since high levels of antibody is known to be toxic to E. coli (Parmley and Smith, 1988, Wilson and Finlay, 1998). Therefore, it may be an advantage to have clones with low levels of scFv on coat protein since such clones probably have growth advantage and could be easily selected. Recently, functional phage clones with in-frame stop codons or out-of-frame gene fusion have been reported (Jacobsson and Frykberg, 1995, Carcamo et al., 1998). This report describes that the in-frame stop codons are also tolerated in phage antibody expression.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Dr H. Westbury and Dr B. Eaton for their support. HSN was supported by Professor Frank Fenner fellowship.

References

- Bird R.E., Hardman K.D., Jacobson H.W., Johnson S., Kaufman B.M., Lee S.M., Lee T., Pope S.H., Riordan G.S., Whitlow M. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science. 1988;242:423–426. doi: 10.1126/science.3140379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton D.R., Barbas C.F. Human antibodies from combinatorial libraries. Adv. Immunol. 1994;57:191–280. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60674-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carcamo J., Ravera M.W., Brissette R., Dedova O., Beasley J.R., Alam-Moghe A., Wan C., Blume A., Mandecki W. Unexpected frameshifts from gene to expressed protein in a phage-displayed peptide library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:11146–11151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S.W., Bye J.M., Jackson P., Allain J.P. Human recombinant antibodies specific for hepatitis C virus core and envelope E2 peptides from an immune phage display library. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:2531–2539. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-10-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton B.T., Gould A.R., Hyatt A.D., Coupar B.E., Martyn J.C., White J.R. A bluetongue serogroup-reactive epitope in the amino terminal half of the major core protein VP7 is accessible on the surface of bluetongue virus particles. Virology. 1991;180:687–696. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90082-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster N.M., Metcalf H.E., Barber T.L., Jones R.H., Luedke A.J. Bluetongue and epizootic hemorrhagic disease virus isolation from vertebrate and invertebrate hosts at a common geographic site. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1980;176:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franconi R., Roggero P., Pirazzi P., Arias F.J., Desiderio A., Bitti O., Pashkoulov D., Mattei B., Bracci L., Masenga V., Milne R.G., Benvenuto E. Functional expression in bacteria and plants of an scFv antibody fragment against tospoviruses. Immunotechnology. 1999;4:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s1380-2933(98)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huismans H., Erasmus B.J. Identification of serotype-specific and group-specific antigens of bluetongue virus. Onderstpoort J. Vet. Res. 1981;48:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston J.S., Levinson D., Mudgett-Hunter M., Tai M.S., Novonty J.S., Margolies M.N., Ridge R.J., Bruccoleri R.E., Haber E., Crea R., Opperman H. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5879–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson K., Frykberg L. Phage display shot-gun cloning of ligand-binding domains of prokaryotic receptors approaches 100% correct clones. BioTechniques. 1995;20:1070–1081. doi: 10.2144/96206rr04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre A., Yu M.W., Chagon F., Talbot P.J. A recombinant single chain antibody neutralizes coronavirus infectivity but only slightly delays lethal infection of mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:3447–3455. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley G.G., Dolezal O., Hillyard C.J., Bernard C., Hudson P.J. Recombinant single-chain antibody peptide conjugates expressed in Escherichia coli for the rapid diagnosis of HIV. J. Immunol. Methods. 1994;171:211–226. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt R.A., White J.R., Blacksell S.D. Evaluation of a monoclonal antibody blocking ELISA for the detection of group-specific antibodies to bluetongue virus in experimental and field sera. J. Gen. Virol. 1988;69:2729–2740. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-11-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis T., Fritz E.F., Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn J.C., Gould A.R., Eaton B.T. High level expression of the major core protein VP7 and the non-structural protein NS3 of bluetongue virus in yeast: use of expressed VP7 as a diagnostic, group-reactive antigen in a blocking ELISA. Virus Res. 1990;18:165–178. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(91)90016-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCafferty J., Griffiths A.D., Winter G., Chiswell D.J. Phage antibodies: filamentous phage displaying antibody variable domains. Nature. 1990;348:552–554. doi: 10.1038/348552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller B.H., Lafay F., Demangel C., Perrin P., Tordo N., Flamand A., Lafaye P., Guesdon J.L. Phage-displayed and soluble mouse scFv fragments neutralize rabies virus. J. Virol. Methods. 1997;67:221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmely S.F., Smith G.P. Antibody-selectable filamentous fd phage vectors: affinity purificaion of target genes. Gene. 1988;73:305–318. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson S.M., Swainsbury R., Routledge E.G. Antigen-specific membrane fusion mediated by the haemagglutinin protein of influenza A virus: separation of attachment and fusion functions on different molecules. Gene Ther. 1999;6:694–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavladoraki P., Benvenuto E., Trinca S., De Martinis D., Cattaneo A., Galeffi P. Transgenic plants expressing a functional single-chain Fv antibody are specifically protected from virus attack. Nature. 1993;366:469–472. doi: 10.1038/366469a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.R., Finlay B.B. Phage display: applications, innovations, and issues in phage and host biology. Can. J. Microbiol. 1998;44:313–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter G., Griffiths A.D., Hawkins R.E., Hoogenboom H.R. Making antibodies by phage display technology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994;12:433–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Hayashi N., Takehara T., Ueda K., Mita E., Tatsumi T., Sasaki Y., Kasahara A., Hori M. Intracellular single-chain antibody against hepatitis B virus core protein inhibits the replication of hepatitis B virus in cultured cells. Hepatology. 1999;30:300–307. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y.Z., Hyatt A., Wang L.F., Eaton B.T., Greenfield P.F., Reid S. Quantification of recombinant core-like particles of bluetongue virus using immunosorbent electron microscopy. J. Virol. Methods. 1999;80:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0166-0934(98)00170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]