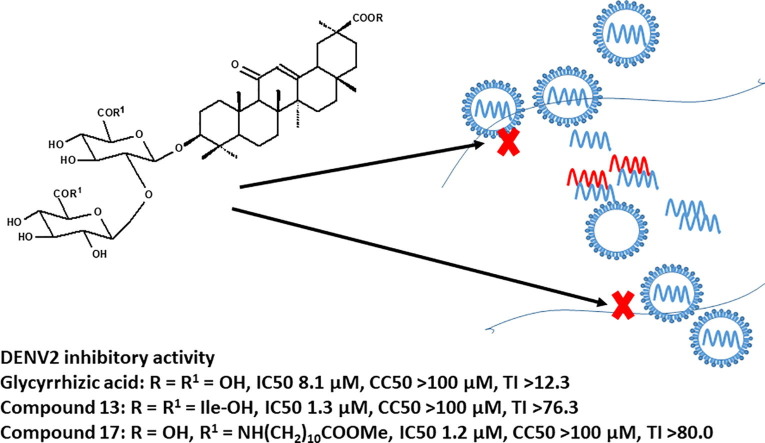

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Glycyrrhizic acid, Derivatives, Dengue virus, Antiviral activity

Highlights

-

•

It is the first report to display structure-anti-DENV activity relationships of Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) derivatives.

-

•

GL conjugates with isoleucine 13 and 11-aminoundecanoic acid 17 have been identified as potent DENV2 inhibitors.

-

•

GL derivatives 13 and 17 showed lower IC50 values (1.2–1.3 μM) against DENV2 infectivity in Vero E6 cells than GL (IC50 8.1 μM).

Abstract

Dengue virus (DENV) is one of the most geographically distributed pathogenic flaviviruses transmitted by mosquitoes Aedes sps. In this study, the structure-antiviral activity relationships of Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) derivatives was evaluated by the inhibitory assays on the cytopathic effect (CPE) and viral infectivity of DENV type 2 (DENV2) in Vero E6 cells. GL (96% purity) had a low cytotoxicity to Vero E6 cells, inhibited DENV2-induced CPE, and reduced the DENV-2 infectivity with the IC50 of 8.1 μM. Conjugation of GL with amino acids or their methyl esters and the introduction of aromatic acylhydrazide residues into the carbohydrate part strongly influenced on the antiviral activity. Among compounds tested GL conjugates with isoleucine 13 and 11-aminoundecanoic acid 17 were found as potent anti-DENV2 inhibitors (IC50 1.2–1.3 μM). Therefore, modification of GL is a perspective way in the search of new antivirals against DENV2 infection.

Dengue virus (DENV) is one of the most geographically distributed pathogenic flaviviruses transmitted by mosquitoes Aedes sps. DENV re-emerges in recent years and poses a threat to the health of the population of more than 100 countries around the world, as considered one of the greatest virus threats to mankind.1, 2 Over the past 50 years, the incidence of Dengue fever has increased 30-fold as a result of its expansion into new countries. The number of cases of infection with DENV in the world is 50–100 million people annually, including 250,000–500,000 cases of Dengue hemorrhagic fever and 24,000 deaths. The Dengue fever epidemic is a serious public health problem in Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Cambodia, the Philippines, Laos, Vietnam, and India, where DENV infection is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death in children.3, 4, 5

Due to the expanding geographic expansion of DENV and the mosquitoes carrying Aedes sps., an increase in the frequency of epidemics, and the emergence of Dengue fever in new areas, WHO declares DENV the main virus threat to humanity.6 According to the antigenic structure, DENV is close to the yellow fever virus and is divided into four serotypes (DENV1–DENV4) that cause Dengue fever, Dengue hemorrhagic fever and Dengue shock syndrome, which leads to death. Infection with a one serotype of the virus provides long-term resistance to this serotype, but does not lead to the development of immunity from other serotypes.7 DENV2 infection manifests itself as a hemorrhagic fever, which is characterized by increased viremia, vascular permeability and is characterized by high blood plasma levels of TNF, TNFR1, TNFR2, IFN, CXCL8, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL5, VEGFA and IL-10.8, 9 Despite the increasing number of outbreaks of Dengue fever in the last decade, there are currently no licensed vaccines and specific chemotherapy against this infection.10 Thus, the search of new antiviral agents against DENV is one of urgent problems of medicinal chemistry and virology.

One of the priority areas in the development of antiviral drugs is the use as scaffolds plant’s derived natural compounds with established antiviral activity and a new mechanism of antiviral action.11, 12 The chemical modification of available plant metabolites, the screening of antiviral activity of modifiers, the study of the structure-activity relationships and the choice of lead compounds are a necessary stage and scientific basis for the creation of new effective antiviral agents for the treatment and prevention of viral infections caused by pathogenic viruses.

Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) (1) is the leading natural triterpene glycoside, promising as a basis for the development of new antiviral agents.13, 14 GL inhibits a number of DNA and RNA viruses (Vaccinia, New Castle, Vesicular stomatitis, varicella-zoster, Herpes simplex type 1, Herpes B), influenza viruses, cytomegaloviruses, hepatitis B and C. GL is used clinically for the treatment of chronic viral hepatitis B and C in Japan and China (SNMC preparations, Compound Glycyrrhizin Ingecpion Injection, Compound Glycyrrhizin Ingecpion Tablets).15, 16 GL inhibits the reproduction of HIV-1 in the culture of MT-4 cells and is suggested for long-term therapy for HIV-infected patients in combination with other anti-HIV drugs.14, 17 GL also affects other cellular factors, such as protein kinase II, casein kinase II and transcription factors (activating protein I and nuclear factor kB).17

Chemical modification of GL is a promising way of obtaining new immune modulators and antiviral agents. Early we synthesized a series of amides, amino acid and dipeptide conjugates, which exceed the natural glycoside by anti-HIV activity.18, 19 GL and its derivatives constitute the first group of substances that inhibit the Marburg virus, which causes acute hemorrhagic fever with a high level of lethality.20 The inhibitory effect has been found for GL derivatives in vitro against SARS-associated coronaviruses.21 Among GL derivatives inhibitors of the Epstein-Barr virus were found.22 Most recently, we detected inhibitory effects of GL derivatives in vitro against influenza A/H1N1 virus.23, 24

GL is also of interest as a scaffold for the preparation of potential inhibitors of pathogenic flaviviruses like DENV, since it is reported about the GL ability to inhibit DENV and yellow fever viruses at high non-toxic concentrations.25. The antiviral activity of GL and its derivatives is associated with the ability to potentiate ϒ-interferon production in vitro and in vivo. The stimulating effect of GL was noted on the secretion of IL-2, inducing the production of interferon by peripheral lymphocytes.13, 14 The antiviral activity of GL derivatives against DENV was not studied else.

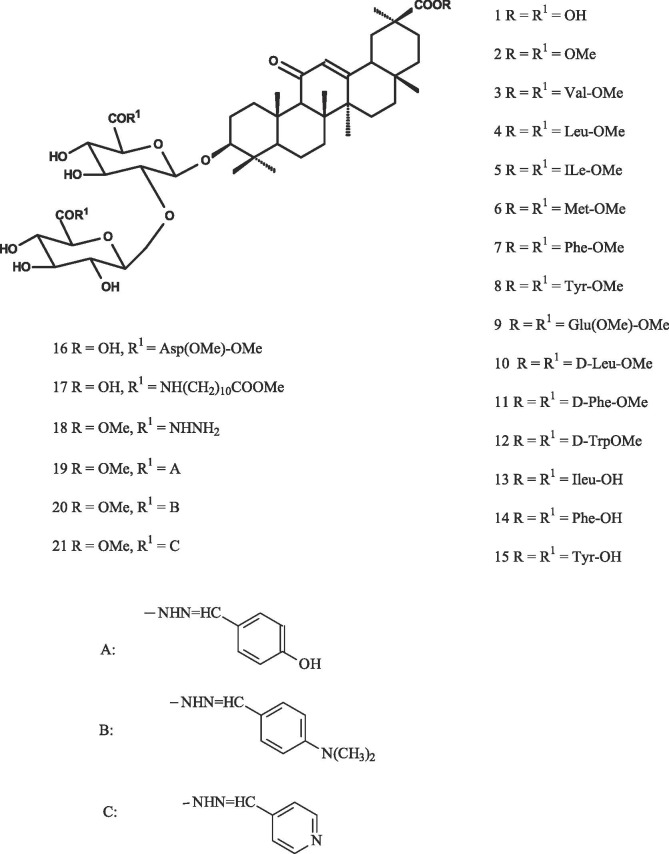

In this study, we report firstly about the antiviral activity of GL derivatives (2–21) (Fig. 1 ) to be conjugates with l- and d-amino acids and their methyl esters and aromatic acylhydrizides against DENV2 and the structure-antiviral activity regularities for those compounds.

Fig. 1.

Structure of GL and it’s derivatives (Compounds 2–21).

GL derivatives used in the study were divided into 3 groups. Group I (compounds 3–15) are GL conjugates containing three free amino acids or their methyl esters residues. Group II (compounds 16, 17) is presented by GL conjugates containing amino components in the carbohydrate part of glycoside. Group III includes acyl hydrazide (18–21) with C30-methyl ester at the R position and residues at the R′ position in GL derivatives.

GL was produced from its mono ammonium salt according to Refs.26, 27 and had a purity 96.0 ± 1.0% (HPLC). Trimethyl ester (2) was produced from GL by using diazometane.28 GL conjugates with amino acids esters (3–12) were prepared by using N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt), N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) or 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (DEC) as we described previously.29, 30, 31 GL conjugates (10–12), containing d-amino acids methyl esters, were synthesized according to Ref.24, conjugates (13–14) with free amino acids according to Refs.32, 33. Compounds (16, 17) containing the residues of aspartic and 11-amino undecanoic acid methyl esters in the carbohydrate part of GL were produced by using N-hydroxysuccinimide (HOSu) and DCC.34, 35 The analytical and spectral data of GL derivatives 2–17 were identical to the literature data, the purity of compounds was monitored by thin layer chromatography and high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (˃95% of purity) (in the Supplementary Material, Supplemental Figs. 1-3).

To expand the library of GL derivatives for testing GL derivatives 18–21 were produced by the modification of GL with the introduction of aromatic acyl hydrazide residues in the carbohydrate part. General experimental details, analytical and spectral data (IR and 13C) for new compounds (18–21) are given in the Supplemental data. Bis-hydrazide of GL 18 was obtained from GL trimethyl ester 2 by reflux with hydrazine hydrate in methanol with 77% yield. The ester methyl group in the aglycone of compound 18 is retained, it was confirmed by the presence of C-30 and OCH3 shifts at 177.1 and 51.9 ppm in the 13C NMR spectrum. Aromatic acyl-hydrazides (19–21) were produced by the reaction of 18 with aromatic aldehydes in ethanol at reflux for 3 h and target compounds were isolated by column chromatography (CC) on silica gel (SG) with 72–74% yields. The structures of compounds 18–21 were confirmed by IR and 13C NMR spectrum. In the 13C NMR spectrum of compounds 18–21 the carbon atoms of the new CH N bonds are detected at 146.2–148.6 ppm, and a set of signals of aromatic carbon atoms appears in the weak field region (131.9–115.5 ppm). 13C NMR spectrum of bis-(pyridine-4-carbal)-hydrazide 21 contains shifts of carbon atoms of pyridine residues in the weak field region (142.7–121.4 ppm). The elemental analysis of all compounds corresponded to the calculated data (see the Supplementary material).

The primary screening of cytotoxicity and antiviral activity of GL and a number of its derivatives (compounds 3–21) was performed in vitro against DENV2 (the strain 16681). Cytotoxicity and antiviral activity were investigated in Vero E6 cell culture in supporting Dulbecco modified medium (DMEM). An MTT cytotoxicity test for each compound was performed in a Vero E6 cell culture in 96-well plates, as described in our previous report.36 The cytotoxic (50%) concentration (CC50) was calculated according to cell survival rate of treated cells compared to mock cells using a computer program (John Spouge, NCBI, NIH). GL (96% purity) was used in the study of antiviral activity as a reference sample. It was established that for GL and its derivatives, the CC50 exceeded 100 μM (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Antiviral activity of GL derivatives against DENV2 in Vero E6 cells.

| Compounds | CPE reduction at 10 μM | Inhibition of NS4B-positive cells (%) at 10 μMa | Cytotoxicity to Vero cells (CC50, μM)b | Reduction in virus-infected cells (IC50, μM)c | TI (CC50/IC50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ++ | 70.5 | ˃100 | 8.1 | ˃12.3 |

| 3 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 4 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 5 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | ++ | 66.3 | ˃100 | 4.5 | ˃22.2 |

| 7 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 8 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 9 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 10 | + | 53.1 | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 13 | +++ | 95.7 | ˃100 | 1.3 | ˃76.3 |

| 14 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | ++ | 68.5 | ˃100 | 2.2 | ˃46.5 |

| 16 | + | 35.8 | ND | ND | ND |

| 17 | +++ | 79.5 | ˃100 | 1.2 | ˃80 |

| 18 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 19 | + | 32.5 | ND | ND | ND |

| 20 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

| 21 | − | – | ND | ND | ND |

ND – not detected.

Inhibitory rate = (1 − NS4B positive percentage in treated infected cells/NS4B positive percentage in mock-treated infected cells) * 100.

CC50, 50% cytototoxic concentration determined by the survival rate of treated cells at different concentrations of each compound.

IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration calculated according to NS4B positive percentage in the presence of different concentrations of each compound.

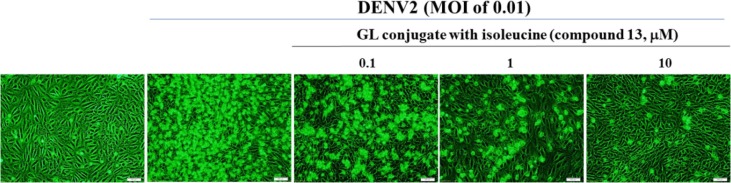

To determine the antiviral activity, a screening study of the cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction was initially conducted in Vero E6 cells infected with the DENV2 virus (MOI of 0.01) in the presence of 10 μM of the test compound. After 96 h of incubation, infected cells were photographed using reverse phase contrast microscopy. Microscopic photographs showed that GL and some of its derivatives at a concentration of 10 μM significantly reduce CPE in cells infected with DENV2. GL had low cytotoxicity to Vero E6 cells,1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 concentration-dependently inhibited CPE and NS4B positive cells (70.5% inhibition) post DENV-2 infection. The most active GL conjugates 6, 13, 15, and 17 (Table 1) proved the significant CPE reduction in the infected cells, representing greater than 50% inhibition on the ratio of DENV2 NS4B-positive cells of infected cells treated with 10 μM indicated derivatives. The antiviral activity of GL and its active derivatives to reduce DENV2 CPE and infectivity was studied in a concentration-dependent manner (0, 0.1, 1, 10 μM). GL and its active derivatives dose-dependently inhibited DENV2-induced CPE in Vero E6 cells. GL conjugate with isoleucine (compound 13) showed the highest inhibitory activity on DENV2-induced CPE at the concentration of 10 μM (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of DENV2-induced cytopathic effects by GL conjugate with isoleucine (Compound 13). Vero E6 cells were infected with DENV2 at a MOI of 0.01 and immediately treated with the indicated concentrations of compound 13. Images of DENV2-induced cytopathic effect were photographed 96 h post infection by phase-contrast microscopy.

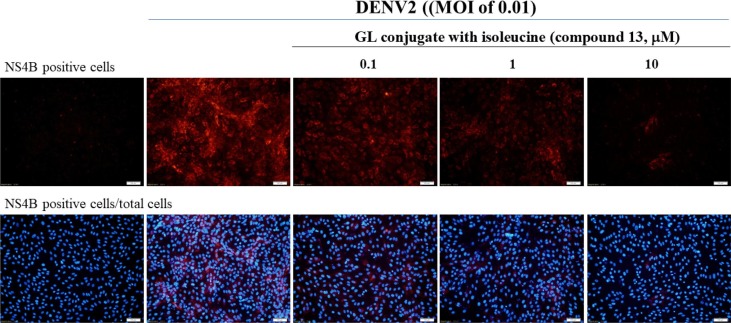

To assess the values of 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50), a quantitative analysis of the inhibitory effect of GL and its active derivatives on the infectivity of DENV2 was carried out in vitro by the immunofluorescence method.36 The infectivity of virus was determined as the ratio of NS4B-positive cells to the total number of cells stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). This analysis has demonstrated that GL and its active derivatives (6, 13, 15, and 17) reduced the number of infected DENV-2 cells (viral NS4B-positive cells) in a dose-dependent form. For example, the rates of NS4B-positive cells were 36.9%, 37.2%, 29.4%, and 1.6% in 0.1, 1 and 10 μM compound 13-treated infected cells, respectively (Fig. 3 ). Meanwhile, the inhibitory rate on DENV2 was 20.2%, and 95.7% by 1 and 10 μM compound 13, respectively. In addition, human lung epithelial A549 cells were used to examine the antiviral activity of GL derivative 13 against DENV2 (Supplemental Fig. 4), in which GL derivative 13 exhibited the potent anti-DENV2 activity in a cell-type independent manner. GL derivatives 13 and 15, containing free amino acids residues (Ile-OH) and (Tyr-OH), and 17 with two long chain amino acid fragments, were found as highly active against anti-DENV2 (IC50 values of 1.3–2.2 μM), as significantly more potent than GL (IC50 of 8.1 μM) (Table 1). In addition, compounds 13 and 17 exhibited the higher therapeutic index (TI, TI = CC50/IC50) than 70, which was 6-fold greater than that of GL. Tyrosine containing conjugate 15 was less active than 13 and 17.

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of DENV2 infectivity by GL conjugate with isoleucine (Compound 13). Vero E6 cells infected with DENV2 (MOI of 0.01) were analyzed using immunofluorescence staining with anti-DENV2 NS4B antibodies after a 96-h treatment with the indicated concentrations of compound 13. ZENV2 infectivity was discovered by the ratio of DENV2 NS4B positive cells (top) to total cells stained with DAPI.

Among group I GL derivatives, conjugates 3–5 and 7–12 with amino acid methyl esters at the R and R′ positions were less active than GL against DENV2. Only conjugate 6 containing Met-OMe fragments showed a significant inhibition on the in vitro replication of DENV2 and its IC50 (4.5 μM) was less than for GL. The anti-DENV activity of conjugate 6 could be linked with the introduction of Met-OMe at the R position of triterpene part, in which an S-methyl thioether side chain of methionine might form NH⋯S H-bonds with the residues of DENV2 target protein. Conjugates 13 and 15 containing Ile-OH and Tyr-OH at the R and R’ positions refined anti-DENV activity (IC50 of 1.3–2.2 μM), but conjugate 14 with Phe-OH dropped the anti-DENV activity. The finding inferred that the –OH group of tyrosine plays the important role in donating or accepting a hydrogen bond with the residues of viral target protein. A weak inhibitory activity on CPE test and NS4B-positive cells was found for compound 16 with a free triterpene COOH group and Asp(OMe)-OMe in the carbohydrate portion of GL. However, compound 17 containing 11-amino undecanoic acid methyl ester exhibited the potent efficacy on inhibiting the DENV2 replication (IC50 of 1.2 μM). Those results indicated that 11-amino undecanoic acid methyl ester at the R′ position in the carbohydrate part of GL had a more effective interaction with the antiviral target(s) than conjugate 16. GL derivatives of group III (18–21) lost the antiviral activity against DENV2. A weak inhibition (32.5%) of NS4B in DENV2-infected cells was found for compound 19 containing aromatic hydroxyl group. Therefore, the structure–antiviral activity study indicated that GL conjugates with three free amino acids (compounds 13, 15) and long chain amino acid residue in the carbohydrate part (compound 15) exhibited higher anti-DENV activity compared to group III derivatives. Thus, the presence of hydroxyl group at the R position of triterpene part or free carboxyl groups of amino acids are important for interacting with antiviral target(s). Meanwhile, GL derivatives 13, 15, and 17 are compounds with the significantly improved antiviral activity against DENV2 infection, suggesting that isoleucine, tyrosine, or 11-amino undecanoic acid methyl ester at the R′ position of the carbohydrate part also interconnected with the other part of active side of antiviral target(s).

We concluded that this study was the first report to display structure-anti-DENV activity relationships of GL derivatives, revealing that the modification of GL by the conjugation with amino acids and the introduction of aromatic acyl hydrazide residues into the carbohydrate part strongly influenced on the antiviral activity of GL against DENV2. Among GL derivatives tested, GL compounds 13 32 and 17 35 have been identified as potent DENV2 inhibitors. Thus, the conjugation of GL derivatives with amino acids is a perspective way to produce potent DENV2 inhibitors. The second way to potentiate GL activity is its modification with the introducing of long chain amino acids in the carbohydrate part of the molecule keeping triterpene COOH group free. Highly active GL derivatives will be the subject of extensive research on antiviral activity and the study of the mechanisms of antiviral action against DENV2 by using docking studies and their interaction with DENV2 targets like NS2B-NS3 protease, NS3 helicase, and NS5 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant 18-53-52004_MNT_a), the state assignment AAAA-A18-118020590121-6 and by China Medical University under the Aim for Top University Plan of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (CHM106-6-2, CMU106-BC-1, CMU106-ASIA-06, and CMU107-ASIA-12) and funded by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST107-2923-B-039-001-MY3).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126645.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kyle J.L., Harris E. Global spread and persistence of dengue. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.163005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guzman M.G., Halstead S.B., Artsob H., et al. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;12:S7–S16. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gubler D.J. Dengue, urbanization and globalization: the unholy trinity of the 21st century. Trop Med Health. 2011;39:3–11. doi: 10.2149/tmh.2011-S05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilder-Smith A., Ooi E.-E., Vasudevan S.G., Gubler D.J. Update on Dengue: epidemiology, virus evolution, antiviral drugs, and vaccine development. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons C.P., Farrar J.J., Chau N., Wills B. Dengue. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1423–1432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1110265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dengue: Guedelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed]

- 7.Avirutnan P., Fuchs A., Hauhart R.E., et al. Antagonism of the complement component C4 by flavivirus nonstructural protein NS1. J Exp Med. 2010;207:793–806. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond M.S., Pierson T.C. Molecular insight into Dengue virus pathogenesis and its implications for disease control. Cell. 2015;162:488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens A.J., Gahan M.E., Mahalingam S., Keller P.A. The medicinal chemistry of dengue fever. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7911–7926. doi: 10.1021/jm900652e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halstead S.B. Dengue vaccine development: a 75% solution? Lancet. 2012;380:1535–1536. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61510-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez J.P., Sasse F., Bronstrup M., Diez J., Meyerhans A. Antiviral drug discovery: broad-spectrum drugs from nature. Nat Prod Rep. 2015;32:29–48. doi: 10.1039/c4np00085d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes E.C., Kumar R., Davis R.A. The use of isolated natural products as scaffolds for the generation of chemically diverse screening libraries for drug discovery. Nat Prod Rep. 2016;33:372–381. doi: 10.1039/c5np00121h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pompei R., Laconi S., Ingianni A. Antiviral properties of Glycyrrhizic acid and its semisynthetic derivatives. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:996–1001. doi: 10.2174/138955709788681636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baltina L.A., Kondratenko R.M., Baltina L.A., Jr., Plyasunova O.A., Pokrovskyi A.G., Tolstikov G.A. Prospects for the creation of new antiviral drugs based on Glycyrrhizic acid and its derivatives. Pharm Chem J. 2009;43:539–548. doi: 10.1007/s11094-010-0348-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato H., Goto W., Yamamura J., et al. Therapeutic basis of glycyrrhizin in chronic hepatitis B. Antiviral Res. 1996;30:171–177. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(96)00942-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsumoto Y., Matsuura T., Aoyagi H., et al. Antiviral activity of Glycyrrhizin against hepatitis C virus in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Clerq E. Current lead natural products for the chemotherapy of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Med Res Rev. 2000;20:323–349. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200009)20:5<323::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondratenko R.M., Baltina L.A., Baltina L.A., Jr., Plyasunova O.A., Pokrovskyi A.G., Tolstikov G.A. Synthesis of new hetero- and carbocyclic aromatic amides of Glycyrrhizic acid as potential anti-HIV agents. Pharm Chem J. 2009;43:383–388. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baltina L. Chemical modification of Glycyrrhizic acid as a route to new bioactive compounds for medicine. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:155–171. doi: 10.2174/0929867033368538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pokrovskyi A.G., Belanov E.F., Volkov G.N., Plyasunova O.A., Tolstikov G.A. Inhibition of Marburg virus reproduction by Glycyrrhizic acid and its derivatives. Reports RAS. 1995;344:709–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoever G., Baltina L.A., Michaelis M., Kondratenko R., Baltina L.A., Jr., Tolstikov G.A. Antiviral activity of Glycyrrhizic acid derivatives against SARS-Coronavirus. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1256–1259. doi: 10.1021/jm0493008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin J.C., Cherng J.M., Hung M.S., Baltina L.A., Baltina L.A., Kondratenko R.M. Inhibitory effects of some derivatives of Glycyrrhizic acid against Epstein-Barr virus infection: structure-activity relationships. Antiviral Res. 2008;79:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.01.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baltina L.A., Zarubaev V.V., Baltina L.A., et al. Glycyrrhizic acid derivatives as influenza A/H1N1 virus inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:1742–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.02.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayrushina A.I., Baltina L.A., Jr., Baltina L.A., Konovalova N.I., Petrova P.A., Eropkin M.Y. Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel Glycyrrhizic acid conjugates with d-aminoacids. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2017;43:456–462. doi: 10.1134/S1068162017040045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crance J.M., Scaramozzino N., Jouan A., Garin D. Interferon, ribavirin, 6-azauridine and glycyrrhizin: antiviral compounds active against pathogenic flaviviruses. Antiviral Res. 2003;58:73–77. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kondratenko R.M., Baltina L.A., Mustafina S.R., Makarova N.V., Nasyrov K.M., Tolstikov G.A. Crystalline Glycyrrhizic acid synthesized from commercial Glycyrrham. Immunomodulant properties of high-purity Glycyrrhizic acid. Pharm Chem J. 2001;35:101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolstikov G.A., Baltina L.A., Grankina V.P., Kondratenko R.M., Tolstikova T.G. Academic Publishing House “Geo”; Novosibirsk: 2007. Licorice: Biodiversity, Chemistry, Application in Medicine; p. 311. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baltina L.A., Kunert O., Fatykhov A.A., et al. High-resolution 1H and 13C NMr of Glycyrrhizic acid and its esters. Chem Nat Compd. 2005;41:432–435. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baltina L.A., Jr., Fairushina A.I., Baltina L.A., et al. Synthesis and antiviral activity of Glycyrrhizic acid conjugates with aromatic amino acids. Chem Nat Compd. 2017;53:1096–1100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baltina L.A., Jr., Fairushina A.I., Baltina L.A. New methods of preparation of carboxy-protected amino acid conjugates of Glycyrrhizic acid. Russ J Gen Chem. 2016;86:826–829. doi: 10.1134/S1070363216040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kondratenko R.M., Baltina L.A., Jr., Baltina L.A., Baschenko N.Z., Tolstikov G.A. Synthesis and immunomodulating activity of new glycopeptides of Glycyrrhizic acid containing residues of l-glutamic acid. Russ J Bioorg Chem. 2006;32:595–601. doi: 10.1134/s1068162006060136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baltina L.A., Jr., Fairushina A.I., Baltina L.A. Synthesis of amino acid conjugates of Glycyrrhizic acid using N-hydroxyphthalimide and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide. Russ J Gen Chem. 2015;85:2735–2738. doi: 10.1134/S1070363215120129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryzhova S.A., Baltina L.A., Tolstikov G.A. Transformations of Glycyrrhizic acid. XI. Synthesis of free glycopeptides. Russ J Gen Chem. 1996;66:157–159. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baltina L.A., Jr., Chistoedova E.S., Baltina L.A., Kondratenko R.M., Plyasunova O.A. Synthesis and anti-HIV-1 activity of new conjugates of 18β- and 18α-Glycyrrhizic acids with aspartic acid esters. Chem Nat Compd. 2012;48:262–266. doi: 10.1007/s10600-012-0217-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baltina L.A., Jr., Stolyarova O.V., Baltina L.A., et al. New amino-acid conjugates of Glycyrrhizic acid. Chem Nat Compd. 2014;50:317–320. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lien J.C., Wang C.Y., Lai H.C., et al. Structure analysis and antiviral activity of CW-33 analogues against Japanese encephalitis virus. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16595. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34932-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.