Introduction to complement

Complement is a major element of the innate immune response and also serves to link innate and adaptive immunity. It is an ancient immunological defence system that is thought to have evolved over 700 million years ago and components have been identified in all vertebrate classes (Zarkadis et al., 2001). Complement comprises over 30 serum and membrane-bound proteins which, when activated, form a cascade of reactions contributing to the elimination of invading microorganisms. Three pathways of activation exist, the classical, lectin, and alternative pathways (outlined in Fig. 1A and reviewed in Walport, 2001), all of which invoke several responses capable of controlling or eliminating infection. This overview will focus on the interaction of viruses with complement, highlighting the protective role of complement against viral infection, the mechanisms used by viruses to evade the effects of complement and the ways in which some viruses can exploit complement to enhance infection. It does not aim to provide a comprehensive analysis but rather an overview of the interaction between viruses and complement. Our intention is to emphasise the growing recognition of the importance of complement to virus biology, revealed through the increasing number of viruses known to have either active or passive (or both) strategies of complement regulating activity.

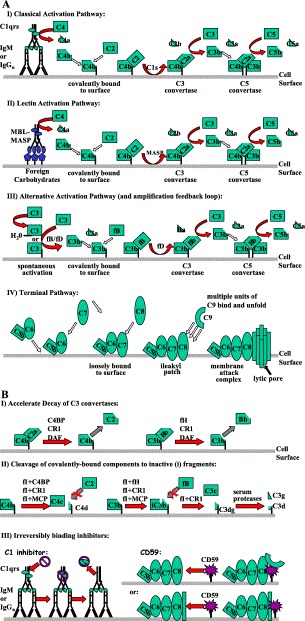

Fig. 1.

Activation pathways of complement (A) and their regulation (B). (A) Three separate routes of complement activation are depicted (I–III). Common to all three pathways is the formation of C3 and C5 convertase enzyme complexes. The C3 convertase (C4b2a or C3bBb) cleaves C3 into C3a (chemotaxin) and C3b. The latter protein forms the C5 convertase, which cleaves C5 to C5a (anaphylatoxin) and C5b. The production of C5b enables the formation of a lytic pore, known as the membrane attack complex (MAC). (I) Activation of the classical pathway results from the binding of C1q to two immunoglobulin Fc regions of antigen-bound IgG and IgM. This binding induces the autolytic cleavage of C1r and the subsequent cleavage of C1s to its active from. Activated C1s cleaves C4. The resulting C4b then binds covalently to the cell surface enabling C2 to bind. C1s then cleaves C2 complexed with C4b, generating the classical C3 convertase, C4b2a. (II) The lectin pathway is triggered in an identical manner except that it is recognized by the mannan-binding lectin (MBL) of foreign carbohydrate that activates the MBL-associated serine proteases (MASP), which are capable of cleaving C4 and C2 to create the C3 convertase, C4b2a. While three separate MASPs have been identified, only MASP-2 can form a C3 convertase (reviewed in Schwaeble et al., 2002). (III) The alternative pathway is continually active, but only amplifies on an activating surface because of insufficient regulation. It also serves as a C3 convertase amplification loop for the other two pathways. The alternative pathway is triggered by the constant low-level spontaneous cleavage of C3 that occurs by nonspecific release of the internal thioester bond. The resulting hydrolysed C3 (either fluid phase or cell-bound) then forms a complex with factor B (fB), which is itself cleaved by serum protease factor D (fD). This complex then generates more C3b and results in the formation of the alternative pathway C3 convertase (C3bBb), which is further stabilised by the association of the serum protein properdin (not shown). (IV) C5b, generated by any of the previous activation pathways, associates noncovalently with C6. This association enables a loose interaction with the membrane surface, which is strengthened by the subsequent noncovalent association of C7 and C8 that causes insertion of the complex into the membrane. The full membrane attack complex consists of a lytic pore formed by the further incorporation of 12–16 molecules of C9. (B) Complement is regulated by several mechanisms (see also Table 1): (I) surface-bound and serum proteins accelerate the decay of the C3 convertases, in many cases, (II) subsequently inducing factor I (fI) cleavage of the covalently attached components of the C3 convertase to fragments that can no longer bind C2 (see AI and AII) or fB (see AIII). (III) Conversely, other regulators act through “suicide” irreversible association with either the terminal complement components (CD59) or the initial C1qrs complex of the classical pathway (C1 inhibitor) resulting in subsequent removal of the C1rs protease complex.

Regulation of complement activity

Complement activation can be potentially damaging to host cells and must therefore be tightly regulated. For this reason, activated components have very short half-lives and are regulated by a large family of host plasma and membrane-bound proteins that are involved in the physiological control of many stages of the complement cascade. Examples of mammalian complement control proteins are given in Table 1 . Complement regulation is based upon three principle mechanisms: (i) accelerated dissociation of the enzymes that cleave C3 and C5, so-called convertase complexes, which mediate the cascade of complement activation; (ii) enzymatic cleavage to inactivate components; and (iii) inactivation following irreversible binding of inhibitors. Host proteins involved in regulating complement include C1 inhibitor, CD59, and a group of proteins known as regulators of complement activation (RCA) (reviewed in Morgan and Harris, 1999). RCA proteins contain structural motifs known as short consensus repeats (SCRs), with each SCR comprising 60–70 amino acids and a conserved motif of di-sulphide-linked cysteines and several hydrophobic residues. RCA proteins only regulate complement components C3b and C4b. Other resistance mechanisms adopted by nucleated cells include the expression of ecto-proteases on their surface that can inactivate complement components by cleavage. Nucleated mammalian cells can also avoid lysis by the terminal complement membrane attack complex (MAC; see below) through shedding or endocytosis of vesicles enriched in MAC components Carney et al., 1985, Carney et al., 1986, Scolding et al., 1989.

Table 1.

Mammalian complement control proteins

| Regulator | Distribution | Function |

|---|---|---|

| C1-inh | soluble | prevents spontaneous activation of C1 and inactivates C1 on surfaces |

| C4-bp* | soluble | accelerates decay of classical pathway C3/C5 convertase; factor I cofactor for degradation of C4b |

| Factor H* | soluble | accelerates decay of alternative pathway C3/C5 convertase; factor I cofactor for degradation of C3b |

| Factor I | soluble | cleaves C3b and C4b to inactive fragments when bound to a regulatory cofactor |

| CR1 (CD35)* | cell-bound | accelerates decay of classical and alternative C3/C5 convertase; factor I cofactor for degradation of C3b and C4b |

| MCP* (CD46) | cell-bound | cofactor for the cleavage of C3b and C4b by factor I |

| DAF* (CD55) | cell-bound | accelerates decay of C3/C5 convertases |

| CD59 | cell-bound | prevents MAC formation |

C1-inhibitor (C1-inh), C4 binding protein (C4-bp), factor H, and factor I are all soluble proteins that regulate the early stages of complement activation. Complement receptor 1 (CR1), membrane cofactor protein (MCP), and decay accelerating factor (DAF) are membrane-bound proteins that act at the level of C3, a central component of the complement cascade. CD59 is a cell surface protein that prevents formation of the terminal membrane attack complex (MAC) involved in membrane disruption and cell lysis. RCA proteins are indicated by an asterisk.

Complement activation during virus infection

Virus infection can activate all three pathways of the complement cascade (see Fig. 1). The classical pathway is activated by the binding of the complement component C1q to antibody–antigen complexes. This activation can also be achieved by C1q binding directly to the glycoproteins of some viruses, in the absence of specific antibodies. These viruses include human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (Spiller and Morgan, 1998) and certain retroviruses Cooper et al., 1976, Solder et al., 1989, such as human T cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV) (Ikeda et al., 1998). The lectin pathway is antibody-independent and is activated upon the interaction of mannan-binding lectin (MBL) with viral surface carbohydrates. This pathway has been implicated in the control of several viral infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV) (Wang, 2003) and influenza Hartshorn et al., 1993, Thielens et al., 2002. The third pathway, the alternative pathway, was originally defined as the antibody-independent activation pathway (as the lectin pathway was not discovered until some decades later). Activation of the alternative pathway is triggered by the continual low-level spontaneous release of the internal thioester bond of C3 to form a tightly regulated C3 convertase. This C3 convertase may either exist in the fluid phase or be attached to the cell surface, if the spontaneous events occur near cells. More importantly, further activation of the alternative pathway only occurs on a foreign or “activating” surface that is determined by a lack of factor H binding to the surface. Factor H binding and regulation of the alternative pathway depends on the addition of sialic acid to carbohydrates found on the cell surface, which can be decreased following infection by some viruses.

Complement activation by all three pathways results in several effector functions that contribute to virus inactivation and elimination. These functions include opsonisation of virions by complement components promoting phagocytosis, virolysis by the MAC, and enhancement of several arms of the immune response through the production of anaphylatoxins and chemotactic factors. Each of these effector functions is discussed below.

Virus opsonisation

Complement components C1q, C3b, and C4b can bind to the virion surface forming a protein coat. This opsonisation can neutralise viral infection in a variety of ways. Phagocytic cells have surface receptors that recognise and bind to C1q, C3b and C4b, promoting uptake and destruction of virions covered with these components (reviewed in Hannan et al., 2002, Krych-Goldberg and Atkinson, 2001, McGreal and Gasque, 2002). Covalent attachment of C3b and C4b to the virion surface may also prevent viral interaction with receptors, uncoating and entry into host cells. Indeed, coating of several viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with C3 has been shown to functionally inactivate the virus in vitro and in vivo (Sullivan et al., 1998). Aggregation of viral particles due to the binding of multivalent complement components, such as C1q and antibodies, can neutralise virus infectivity and also promote phagocytosis via Fc receptors.

Virolysis

Although opsonisation itself can inactivate infectious virions, enveloped viruses are also susceptible to lysis by the MAC. The amphipathic complement components from C5b to C9 combine and insert into the viral envelope to form a transmembrane channel. This channel results in a bidirectional flow of ions and macromolecules, which disrupts viral integrity and eventually leads to osmotic lysis and irreversible loss of viral activity. Alphaviruses, coronaviruses, herpesviruses, and retroviruses are some that are susceptible to killing by the MAC Mochizuki et al., 1990, Spear et al., 1993, Vasantha et al., 1988.

Anaphylatoxin and chemotaxin production

Enzymatic cleavage of complement components C3, C4, and C5 during complement activation results in the production of low molecular weight, biologically active peptides: the anaphylatoxins C3a, C4a, and C5a, respectively (see Fig. 1). Overall, these anaphylatoxins activate many cell types, concomitant with the wide range of cells on which their receptors are expressed (reviewed in Ember and Hugli, 1997, Kohl, 2001). They mediate many inflammatory responses including smooth muscle contraction, enhanced vascular permeability, release of vasoactive amines, and induction of lysosomal enzyme release. C5a is the most potent anaphylatoxin, functioning as a chemoattractant for leukocytes and neutrophils, recruiting them to the region of complement activation and inflammation. C3a may also act as a chemotactic factor for eosinophils and T cells.

Other effects of complement

Complement can play an important role in the induction of humoral immunity against viruses. C3b and iC3b (see Fig. 1B-II) opsonised virions can bind to follicular dendritic cells (FDC) in lymph nodes via the complement receptors CR1 and CR3, which serves to enhance viral antigen presentation to B cells. C3dg (see Fig. 1B-II) combined with viral antigen can also induce cross-linking of the B cell antigen receptor and CR2 on the B cell surface. Indeed, it has been shown that mice deficient in various complement components fail to develop normal memory responses to herpes simplex virus (HSV) (Da Costa et al., 1999). Furthermore, the antigenicity of the HIV envelope glycoproteins encoded by env (and other viral antigens) was augmented by creating a DNA vaccine for evaluation in mice, whereby env was fused to the human or murine genes encoding C3d (Green et al., 2001).

Viral infections associated with complement deficiencies

Hypocomplementaemia is the medical term used to define a condition where a component of complement is lacking or is reduced in concentration. Although deficiencies in components of complement are rare, patients with hypocomplementaemia have been shown to be more susceptible to infection and disease by certain viruses. For example, a positive correlation between hepatitis C virus (HCV) viraemia and hypocomplementaemia has been demonstrated. Furthermore, the severity and frequency of HSV reactivation and nonresponsiveness to HBV vaccination have been linked to C4 deficiency Hohler et al., 2002, Seppanen et al., 2001.

Viral evasion of complement

Viruses have evolved numerous mechanisms to evade the destructive effects of complement. They include passive strategies, for example, where cellular complement regulatory proteins may be incorporated into the envelope of viruses as they bud from the cell surface, and active strategies in which certain viruses encode their own complement regulatory proteins. Some of these mechanisms will be discussed (see also Favoreel et al., 2003, Lee et al., 2003).

Incorporation of host complement regulatory proteins into virus envelopes

The incorporation of host RCA proteins and CD59 during egress from the host cell is a mechanism utilised by some enveloped viruses to protect the cell-free virion from complement-mediated attack. The exact mechanism for this process is unknown but may involve viral budding from certain regions of the cell surface enriched with complement regulatory proteins, such as lipid rafts. Various isolates of HIV can be immunocaptured by anti-membrane cofactor protein (MCP), anti-decay accelerating factor (DAF), and anti-CD59 antibodies, and incorporation of all three proteins has been demonstrated to protect virions from complement-mediated lysis (Saifuddin et al., 1997). Vaccinia virus (VV), HTLV, and HCMV are other examples of viruses that can incorporate host complement regulatory proteins into their envelope, affording protection against complement (Spear et al., 1995).

Prevention of complement activation by antibody–antigen complexes and viral Fc receptors

Some viruses, including psuedorabies virus (PRV), a swine α-herpesvirus, can shed or internalise antibody–antigen complexes from their surface to prevent complement activation or phagocytosis (Van de Walle et al., 2003). Other viruses [HSV, varicella-zoster virus (VZV), HCMV] or virus-infected cells express Fc-like receptors that have been proposed to bind the Fc portion of nonspecific IgG in a conformation that sterically hinders access of specific antivirus antibody or prevents complement activation Antonsson and Johansson, 2001, Dowler and Veltri, 1984, Litwin and Grose, 1992. In this regard, binding of nonimmune IgG to HSV-1-infected cells has been shown to protect them against complement-mediated lysis and to protect HSV-1 virions from antibody neutralisation (Dowler and Veltri, 1984). HIV has been reported to impair complement-mediated phagocytosis of infected cells, possibly by interfering with downstream signalling events (Kedzierska et al., 2003).

Virus-encoded proteins

The larger DNA viruses have the genomic capacity to encode proteins that have complement regulatory activity and several of them have been characterised extensively. Many of the proteins have been identified based on their homology to cellular complement regulatory proteins, but some, including the HSV-1 and -2 gC glycoproteins, show no homology to cellular proteins, and thus may regulate complement by different mechanisms (see below).

i. Host complement control protein homologues

Many members of the herpesvirus and poxvirus families encode complement control protein homologues that are known to inhibit the antiviral effects of complement by different mechanisms. Three γ-herpesviruses, Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV), herpesvirus saimiri (HVS), and murine γ-herpesvirus 68 (MHV68), encode proteins (KCP, CCPH, and MHV68-RCA, respectively) with homology to DAF and MCP, all of which inhibit complement activation Fodor et al., 1995, Kapadia et al., 1999, Spiller et al., 2003b. KSHV KCP comprises three protein isoforms that are thought to be produced by alternative splicing and they all regulate complement activation (Spiller et al., 2003b). KCP can prevent cell surface deposition of C3b, enhance the decay of the classical pathway C3 convertase, and act as a cofactor in a factor I-mediated cleavage reaction (see Fig. 1B-II; Mullick et al., 2003, Spiller et al., 2003a, Spiller et al., 2003b). The HVS CCPH protein shows similar activity to KCP, in that it inhibits C3b deposition and C3 convertase activity (Fodor et al., 1995). A second, distinct complement regulatory protein encoded by HVS, HVS15, is thought to control complement activity by blocking formation of the terminal MAC (Albrecht et al., 1992).

The MHV68 RCA protein can inhibit complement activation by the classical and alternative pathways (Kapadia et al., 1999). Recently, an MHV68 RCA deletion mutant was created to evaluate the contribution of this complement control protein to viral pathogenesis in vivo (Kapadia et al., 2002). The results indicated that the MHV68 RCA protein is required for full virulence in acute and chronic infection and that the attenuated phenotype of the mutant could be reversed by deletion of host C3. Complement was also shown to have a role in regulating latency. Such findings demonstrate the potential importance of complement in γ-herpesvirus infection and that these viruses have evolved successful strategies for evading complement.

Some of the poxviruses such as cowpox, variola, and VV encode functional homologues of complement control proteins, of which the VV complement control protein (VCP) has been most extensively characterised. VCP can accelerate the decay of classical and alternative pathway convertases and acts as a cofactor for factor I-mediated cleavage of C3b and C4b McKenzie et al., 1992, Sahu et al., 1998. VCP is secreted from infected cells, contributes to virulence in animal models, and can prevent antibody-complement dependent neutralisation of VV (Isaacs et al., 1992).

ii. Complement control proteins lacking homology to cellular proteins

The gC glycoproteins of HSV-1 and -2 are the only characterised viral complement control proteins lacking any homology to host complement regulatory proteins. HSV-1gC was the first viral protein identified as binding complement Friedman et al., 1984, Fries et al., 1986. Although the gC glycoproteins of HSV-1 and -2 are highly homologous to one another, they demonstrate significant differences in their ability to regulate complement. HSV-1 gC can accelerate the decay of the alternative pathway convertase and protects HSV-1 against the complement activities of this pathway (Hung et al., 1994). An HSV-1 gC mutant incapable of binding complement has been shown to have reduced pathogenicity in an animal model of infection (Lubinski et al., 1998). HSV-2 gC does not accelerate the decay of the alternative pathway convertase but does provide protection against complement-mediated neutralisation. However, compared to the HSV-1 gC protein, HSV-2 gC demonstrates poor complement regulatory activity. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) also has complement regulatory activity (Mold et al., 1988), but does not encode for any proteins showing homology to host complement regulatory proteins, highlighting that much remains to be understood about these viral proteins.

Other mechanisms

Up-regulation of host RCA on the surface of infected cells has been demonstrated for HCMV, where MCP and DAF expression is up-regulated up to 8-fold (Spiller et al., 1996). Although the mechanism for this regulation has not been determined, up-regulation of DAF has been shown to increase resistance of these infected cells to complement mediated lysis. However, the mechanism of murine CMV up-regulation of MCP has been determined to depend on a cis-acting virus-responsive promoter element in the MCP promoter (Nomura et al., 2002).

Some viruses may recruit protective host complement components to their surface or to the surface of infected cells, in addition to incorporating RCA proteins in their envelope. HIV can bind factor H to its surface, through an interaction with the gp41 and gp120 glycoproteins (Stoiber et al., 1995). This binding has been shown to significantly protect virions from the effects of complement (Stoiber et al., 1996) and promotes the degradation of bound C3b to iC3b that enhances the ability of HIV to interact with FDC.

Sindbis virus is thought to incorporate host sialic acids into its envelope during budding. The amount of sialic acid on cells infected with this virus positively correlates with resistance to complement, presumably through the ability to recruit and bind factor H (Hirsch et al., 1981). Mimicking host surfaces in this way may help avoid complement activation by the alternative pathway.

Latency may also serve as a mechanism to evade complement by preventing the expression of viral antigens on the cell surface that could target the cell for complement-mediated destruction. However, viruses undergoing latent infection must have the ability to evade complement attack once reactivated, as certain herpesviruses seem to do (see above).

Viral exploitation of complement to enhance infection

Many viruses can exploit the complement system to promote infection, either by direct binding to complement receptors (CR) to gain entry to host cells or indirectly through complement-opsonised virus interactions.

Direct binding to complement receptors and regulators

CR are expressed on many tissues and cells, including neutrophils, FDC, B cells, and macrophages. They have an important role in clearing immune complexes, as well as in neutrophil function. It is well established that EBV gains entry to B cells and endothelial cells through interactions between the viral gp350/220 proteins and complement receptor CR2 (Fingeroth et al., 1984), although other receptors, such as certain integrins, have also been shown to be involved (Tugizov et al., 2003). Kinetic studies have indicated that gp350/220 has higher affinity for CR2 than host C3 fragments and would effectively surpass host CR2–C3dg binding (Moore et al., 1989). Complement regulators are also targets for viral binding. MCP has recently been identified as a receptor for group Badenoviruses, since non-permissive cells were rendered susceptible to viral infection by expression of MCP Gaggar et al., 2003, Segerman et al., 2003. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and measles virus (MV) both use MCP as a cellular receptor, although they utilise different domains of this receptor for binding (Greenstone et al., 2002). Identification of MCP as the receptor for MV has led to the development of a transgenic mouse model that has contributed to in vivo studies of viral pathogenesis Horvat et al., 1996, Rall et al., 1997. However, the primary MV receptor, signalling lymphocyte-activation molecule (SLAM) (Tatsuo et al., 2000), is not part of the complement system. Nevertheless, the lack of SLAM in the central nervous system (CNS) suggests that utilisation of MCP by MV may determine the development of the severe CNS complications (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis) sometimes associated with MV infections. Several other viruses, including many enteroviruses, such as echovirus 7 and certain coxsackie viruses, use DAF as a co-receptor Bergelson et al., 1994, Martino et al., 1998, Shafren, 1998, Spiller et al., 2000; binding may not be sufficient to enable viral entry, but rather serve to facilitate interactions with other accessory molecules, hence the use of the term co-receptor. Closely related picornaviruses that bind DAF have been shown to interact with different SCRs of the DAF protein (Powell et al., 1999).

Indirect interactions between viruses and host cells

Coating of viral surfaces with complement components may enhance infection for some viruses, including West Nile virus, HTLV-1, and HIV, via the interaction of virus-bound complement components with host CR Cardosa et al., 1983, Robinson et al., 1990, Saifuddin et al., 1995, Stoiber et al., 1997. HIV either opsonised by complement or immunocomplexed (complement fragments plus antibody) can associate efficiently with cells expressing CR, including FDC, macrophages, monocytes, and B cells. This association can facilitate infection of CD4-positive and -negative cells. For example, infection could be promoted of lymphocytes trafficking through lymphoid tissue by HIV trapped on high-density CR expressed on FDC (Moir et al., 2000). The anaphylatoxin C5a has also been shown to increase the susceptibility of monocyte-derived macrophages to HIV infection (Kacani et al., 2001). Clearly, the interactions between HIV and complement are complex and a fine balance must exist between viral neutralisation and enhancement of infection.

Complement as a therapeutic target

Complement is an important mediator of inflammation and inappropriate or prolonged activation can have undesirable effects. Complement activation may contribute to the pathology of many diseases, including ischaemia reperfusion injury, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and several autoimmune diseases (Makrides, 1998). For this reason, many of human complement inhibitors are currently being investigated as therapeutic agents, targeting various stages of the complement cascade. Several of these inhibitors are currently in clinical trials Holers, 2003, Smith and Smith, 2001 and many potential therapeutic agents have been identified to date. Indeed, the range of viral proteins exhibiting complement-regulatory activity at numerous stages of the complement cascade could also be exploited in the search for novel agents to target complement. Viral proteins may have higher affinity for complement components than host regulatory proteins, as is the case with EBV binding to CR2 via the viral gp350/220 glycoproteins (Moore et al., 1989). However, the immunogenicity of such viral proteins would require consideration.

Viral vectors and gene therapy: role of complement

Viruses are currently the most common vector being developed or being tested in gene therapy trials to correct defective genes. Oncolytic viruses may also be utilised in tumour therapy (Wakimoto et al., 2003). Viruses being exploited for these technologies include retroviruses, adenoviruses, and HSV, and many preliminary studies have reported encouraging results. However, the implementation of gene therapy was severely and tragically compromised by the death of a patient participating in a clinical trial for the correction of a congenic liver defect. Death was due to multiple organ failure, likely induced by a severe inflammatory response to the adenovirus vector. Indeed, it has since been demonstrated that treating isolated human plasma with the same adenovirus serotype, and at concentrations matching those reached during the trial, activates complement to levels that could result in a vigorous inflammatory response (Cichon et al., 2001). Hence, a comprehensive analysis of the host immune response to viral vectors before their use in clinical studies is needed. Such evaluation should consider the ability of the host to eliminate the vector, rendering therapy unsuccessful and the potential of the vector to induce a severe inflammatory response, in which complement may play a significant role.

Concluding remarks

The importance of complement in controlling viral infection is evident from the range of strategies utilised by viruses to evade complement-mediated attack and from the attenuated virulence of viruses with null mutations in complement-control proteins. This review has highlighted some of the interactions between viruses and complement. Many of these interactions are complex. This is the case with HIV, which can trigger all three pathways of complement activation and is susceptible to several of the resulting effects, yet it has also evolved a range of strategies to evade complement and can even utilise complement to enhance infection. Many viral proteins are now known to be capable of regulating complement activation and some may serve as novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of complement-mediated diseases. Most of these viral proteins have been identified based on their homology to known cellular regulators, but several have no known homology to cellular proteins. Hence, not only may viral proteins have mechanisms of complement regulation similar to those of cellular complement regulatory proteins, and provide potential tools for dissection of complement biology, but some may also represent classes of complement regulatory proteins yet to be discovered.

Acknowledgements

Our work is currently supported by grants from The Association for International Cancer Research (DJB: ref. 01-242) and Cancer Research UK (OBS and DJB: ref. C7934). OBS is also supported through a career development grant provided by the Wellcome Trust. We thank G.K. Paterson (University of Glasgow) and Dr. Claire Harris (University of Wales College of Medicine) for critical reading of the manuscript. We regret that the citation of many elegant studies contributing to this field and to the present review was omitted due to space constraints.

References

- Albrecht J.C., Nicholas J., Cameron K.R., Newman C., Fleckenstein B., Honess R.W. Herpesvirus saimiri has a gene specifying a homologue of the cellular membrane glycoprotein CD59. Virology. 1992;190(1):527–530. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91247-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson A., Johansson P.J. Binding of human and animal immunoglobulins to the IgG Fc receptor induced by human cytomegalovirus. J. Gen. Virol. 2001;82(Pt 5):1137–1145. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson J.M., Chan M., Solomon K.R., St. John N.F., Lin H., Finberg R.W. Decay-accelerating factor (CD55), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored complement regulatory protein, is a receptor for several echoviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91(13):6245–6249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardosa M.J., Porterfield J.S., Gordon S. Complement receptor mediates enhanced flavivirus replication in macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 1983;158(1):258–263. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney D.F., Koski C.L., Shin M.L. Elimination of terminal complement intermediates from the plasma membrane of nucleated cells: the rate of disappearance differs for cells carrying C5b-7 or C5b-8 or a mixture of C5b-8 with a limited number of C5b-9. J. Immunol. 1985;134(3):1804–1809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney D.F., Hammer C.H., Shin M.L. Elimination of terminal complement complexes in the plasma membrane of nucleated cells: influence of extracellular Ca2+ and association with cellular Ca2+ J. Immunol. 1986;137(1):263–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cichon G., Boeckh-Herwig S., Schmidt H.H., Wehnes E., Muller T., Pring-Akerblom P., Burger R. Complement activation by recombinant adenoviruses. Gene Ther. 2001;8(23):1794–1800. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper N.R., Jensen F.C., Welsh R.M., Jr., Oldstone M.B. Lysis of RNA tumor viruses by human serum: direct antibody-independent triggering of the classical complement pathway. J. Exp. Med. 1976;144(4):970–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.4.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa X.J., Brockman M.A., Alicot E., Ma M., Fischer M.B., Zhou X., Knipe D.M., Carroll M.C. Humoral response to herpes simplex virus is complement-dependent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96(22):12708–12712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowler K.W., Veltri R.W. In vitro neutralization of HSV-2: inhibition by binding of normal IgG and purified Fc to virion Fc receptor (FcR) J. Med. Virol. 1984;13(3):251–259. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890130307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ember J.A., Hugli T.E. Complement factors and their receptors. Immunopharmacology. 1997;38(1–2):3–15. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(97)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favoreel H.W., Van de Walle G.R., Nauwynck H.J., Pensaert M.B. Virus complement evasion strategies. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84(Pt 1):1–15. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingeroth J.D., Weis J.J., Tedder T.F., Strominger J.L., Biro P.A., Fearon D.T. Epstein–Barr virus receptor of human B lymphocytes is the C3d receptor CR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81(14):4510–4514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodor W.L., Rollins S.A., Bianco-Caron S., Rother R.P., Guilmette E.R., Burton W.V., Albrecht J.C., Fleckenstein B., Squinto S.P. The complement control protein homolog of herpesvirus saimiri regulates serum complement by inhibiting C3 convertase activity. J. Virol. 1995;69(6):3889–3892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3889-3892.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman H.M., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Seidel C.A., Cines D.B. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus 1 acts as a receptor for the C3b complement component on infected cells. Nature. 1984;309(5969):633–635. doi: 10.1038/309633a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries L.F., Friedman H.M., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Hammer C.H., Frank M.M. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus 1 is an inhibitor of the complement cascade. J. Immunol. 1986;137(5):1636–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggar A., Shayakhmetov D., Lieber A. CD46 is a cellular receptor for group B adenoviruses. Nat. Med. 2003;9(11):1408–1412. doi: 10.1038/nm952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green T.D., Newton B.R., Rota P.A., Xu Y., Robinson H.L., Ross T.M. C3d enhancement of neutralizing antibodies to measles hemagglutinin. Vaccine. 2001;20(1–2):242–248. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstone H.L., Santoro F., Lusso P., Berger E.A. Human herpesvirus 6 and measles virus employ distinct CD46 domains for receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(42):39112–39118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannan J., Young K., Szakonyi G., Overduin M.J., Perkins S.J., Chen X., Holers V.M. Structure of complement receptor (CR) 2 and CR2–C3d complexes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30(Pt 6):983–989. doi: 10.1042/bst0300983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorn K.L., Sastry K., White M.R., Anders E.M., Super M., Ezekowitz R.A., Tauber A.I. Human mannose-binding protein functions as an opsonin for influenza A viruses. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;91(4):1414–1420. doi: 10.1172/JCI116345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch R.L., Griffin D.E., Winkelstein J.A. Host modification of Sindbis virus sialic acid content influences alternative complement pathway activation and virus clearance. J. Immunol. 1981;127(5):1740–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohler T., Stradmann-Bellinghausen B., Starke R., Sanger R., Victor A., Rittner C., Schneider P.M. C4A deficiency and nonresponse to hepatitis B vaccination. J. Hepatol. 2002;37(3):387–392. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holers V.M. The complement system as a therapeutic target in autoimmunity. Clin. Immunol. 2003;107(3):140–151. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvat B., Rivailler P., Varior-Krishnan G., Cardoso A., Gerlier D., Rabourdin-Combe C. Transgenic mice expressing human measles virus (MV) receptor CD46 provide cells exhibiting different permissivities to MV infections. J. Virol. 1996;70(10):6673–6681. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6673-6681.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung S.L., Peng C., Kostavasili I., Friedman H.M., Lambris J.D., Eisenberg R.J., Cohen G.H. The interaction of glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 with the alternative complement pathway. Virology. 1994;203(2):299–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F., Haraguchi Y., Jinno A., Iino Y., Morishita Y., Shiraki H., Hoshino H. Human complement component C1q inhibits the infectivity of cell-free HTLV-I. J. Immunol. 1998;161(10):5712–5719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs S.N., Kotwal G.J., Moss B. Vaccinia virus complement-control protein prevents antibody-dependent complement-enhanced neutralization of infectivity and contributes to virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89(2):628–632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacani L., Banki Z., Zwirner J., Schennach H., Bajtay Z., Erdei A., Stoiber H., Dierich M.P. C5a and C5a(desArg) enhance the susceptibility of monocyte-derived macrophages to HIV infection. J. Immunol. 2001;166(5):3410–3415. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia S.B., Molina H., van Berkel V., Speck S.H., Virgin H.W.T. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 encodes a functional regulator of complement activation. J. Virol. 1999;73(9):7658–7670. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7658-7670.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia S.B., Levine B., Speck S.H., Virgin H.W.T. Critical role of complement and viral evasion of complement in acute, persistent, and latent gamma-herpesvirus infection. Immunity. 2002;17(2):143–155. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedzierska K., Azzam R., Ellery P., Mak J., Jaworowski A., Crowe S.M. Defective phagocytosis by human monocyte/macrophages following HIV-1 infection: underlying mechanisms and modulation by adjunctive cytokine therapy. J. Clin. Virol. 2003;26(2):247–263. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl J. Anaphylatoxins and infectious and non-infectious inflammatory diseases. Mol. Immunol. 2001;38(2–3):175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krych-Goldberg M., Atkinson J.P. Structure–function relationships of complement receptor type 1. Immunol. Rev. 2001;180:112–122. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1800110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Jung J.U., Means R.E. ‘Complementing’ viral infection: mechanisms for evading innate immunity. Trends Microbiol. 2003;11(10):449–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin V., Grose C. Herpesviral Fc receptors and their relationship to the human Fc receptors. Immunol. Res. 1992;11(3–4):226–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02919129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubinski J.M., Wang L., Soulika A.M., Burger R., Wetsel R.A., Colten H., Cohen G.H., Eisenberg R.J., Lambris J.D., Friedman H.M. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gC mediates immune evasion in vivo. J. Virol. 1998;72(10):8257–8263. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8257-8263.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides S.C. Therapeutic inhibition of the complement system. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50(1):59–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino T.A., Petric M., Brown M., Aitken K., Gauntt C.J., Richardson C.D., Chow L.H., Liu P.P. Cardiovirulent coxsackieviruses and the decay-accelerating factor (CD55) receptor. Virology. 1998;244(2):302–314. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGreal E., Gasque P. Structure–function studies of the receptors for complement C1q. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002;30(Pt 6):1010–1014. doi: 10.1042/bst0301010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie R., Kotwal G.J., Moss B., Hammer C.H., Frank M.M. Regulation of complement activity by vaccinia virus complement-control protein. J. Infect. Dis. 1992;166(6):1245–1250. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki Y., de Ming T., Hayashi T., Itoh M., Hotta H., Homma M. Protection of mice against Sendai virus pneumonia by non-neutralizing anti-F monoclonal antibodies. Microbiol. Immunol. 1990;34(2):171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moir S., Malaspina A., Li Y., Chun T.W., Lowe T., Adelsberger J., Baseler M., Ehler L.A., Liu S., Davey R.T., Jr., Mican J.A., Fauci A.S. B cells of HIV-1-infected patients bind virions through CD21–complement interactions and transmit infectious virus to activated T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192(5):637–646. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mold C., Bradt B.M., Nemerow G.R., Cooper N.R. Epstein–Barr virus regulates activation and processing of the third component of complement. J. Exp. Med. 1988;168(3):949–969. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore M.D., DiScipio R.G., Cooper N.R., Nemerow G.R. Hydrodynamic, electron microscopic, and ligand-binding analysis of the Epstein–Barr virus/C3dg receptor (CR2) J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264(34):20576–20582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B.P., Harris C.L. Academic Press; London: 1999. Complement Regulatory Proteins. [Google Scholar]

- Mullick J., Bernet J., Singh A.K., Lambris J.D., Sahu A. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) open reading frame 4 protein (kaposica) is a functional homolog of complement control proteins. J. Virol. 2003;77(6):3878–3881. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3878-3881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M., Kurita-Taniguchi M., Kondo K., Inoue N., Matsumoto M., Yamanishi K., Okabe M., Seya T. Mechanism of host cell protection from complement in murine cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection: identification of a CMV-responsive element in the CD46 promoter region. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32(10):2954–2964. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2002010)32:10<2954::AID-IMMU2954>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell R.M., Ward T., Goodfellow I., Almond J.W., Evans D.J. Mapping the binding domains on decay accelerating factor (DAF) for haemagglutinating enteroviruses: implications for the evolution of a DAF-binding phenotype. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80(Pt 12):3145–3152. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall G.F., Manchester M., Daniels L.R., Callahan E.M., Belman A.R., Oldstone M.B. A transgenic mouse model for measles virus infection of the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94(9):4659–4663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson W.E., Jr., Kawamura T., Gorny M.K., Lake D., Xu J.Y., Matsumoto Y., Sugano T., Masuho Y., Mitchell W.M., Hersh E. Human monoclonal antibodies to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 enhance HIV-1 infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1990;87(8):3185–3189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu A., Isaacs S.N., Soulika A.M., Lambris J.D. Interaction of vaccinia virus complement control protein with human complement proteins: factor I-mediated degradation of C3b to iC3b1 inactivates the alternative complement pathway. J. Immunol. 1998;160(11):5596–5604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifuddin M., Landay A.L., Ghassemi M., Patki C., Spear G.T. HTLV-I activates complement leading to increased binding to complement receptor-positive cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1995;11(9):1115–1122. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saifuddin M., Hedayati T., Atkinson J.P., Holguin M.H., Parker C.J., Spear G.T. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 incorporates both glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored CD55 and CD59 and integral membrane CD46 at levels that protect from complement-mediated destruction. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78(Pt 8):1907–1911. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaeble W., Dahl M.R., Thiel S., Stover C., Jensenius J.C. The mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases (MASPs) and MAp19: four components of the lectin pathway activation complex encoded by two genes. Immunobiology. 2002;205(4–5):455–466. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N.J., Morgan B.P., Houston W.A., Linington C., Campbell A.K., Compston D.A. Vesicular removal by oligodendrocytes of membrane attack complexes formed by activated complement. Nature. 1989;339(6226):620–622. doi: 10.1038/339620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerman A., Atkinson J.P., Marttila M., Dennerquist V., Wadell G., Arnberg N. Adenovirus type 11 uses CD46 as a cellular receptor. J. Virol. 2003;77(17):9183–9191. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9183-9191.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppanen M., Lokki M.L., Timonen T., Lappalainen M., Jarva H., Jarvinen A., Sarna S., Valtonen V., Meri S. Complement C4 deficiency and HLA homozygosity in patients with frequent intraoral herpes simplex virus type 1 infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;33(9):1604–1607. doi: 10.1086/323462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafren D.R. Viral cell entry induced by cross-linked decay-accelerating factor. J. Virol. 1998;72(11):9407–9412. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9407-9412.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G.P., Smith R.A. Membrane-targeted complement inhibitors. Mol. Immunol. 2001;38(2–3):249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solder B.M., Schulz T.F., Hengster P., Lower J., Larcher C., Bitterlich G., Kurth R., Wachter H., Dierich M.P. HIV and HIV-infected cells differentially activate the human complement system independent of antibody. Immunol. Lett. 1989;22(2):135–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(89)90180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear G.T., Takefman D.M., Sullivan B.L., Landay A.L., Jennings M.B., Carlson J.R. Anti-cellular antibodies in sera from vaccinated macaques can induce complement-mediated virolysis of human immunodeficiency virus and simian immunodeficiency virus. Virology. 1993;195(2):475–480. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear G.T., Lurain N.S., Parker C.J., Ghassemi M., Payne G.H., Saifuddin M. Host cell-derived complement control proteins CD55 and CD59 are incorporated into the virions of two unrelated enveloped viruses. Human T cell leukemia/lymphoma virus type I (HTLV-I) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) J. Immunol. 1995;155(9):4376–4381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller O.B., Morgan B.P. Antibody-independent activation of the classical complement pathway by cytomegalovirus-infected fibroblasts. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;178(6):1597–1603. doi: 10.1086/314499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller O.B., Morgan B.P., Tufaro F., Devine D.V. Altered expression of host-encoded complement regulators on human cytomegalovirus-infected cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996;26(7):1532–1538. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller O.B., Goodfellow I.G., Evans D.J., Almond J.W., Morgan B.P. Echoviruses and coxsackie B viruses that use human decay-accelerating factor (DAF) as a receptor do not bind the rodent analogues of DAF. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;181(1):340–343. doi: 10.1086/315210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller O.B., Blackbourn D.J., Mark L., Proctor D.G., Blom A.M. Functional activity of the complement regulator encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma associated herpesvirus. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(11):9283–9289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m211579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller O.B., Robinson M., O'Donnell E., Milligan S., Morgan B.P., Davison A.J., Blackbourn D.J. Complement regulation by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF4 protein. J. Virol. 2003;77(1):592–599. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.592-599.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber H., Ebenbichler C., Schneider R., Janatova J., Dierich M.P. Interaction of several complement proteins with gp120 and gp41, the two envelope glycoproteins of HIV-1. AIDS. 1995;9(1):19–26. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber H., Pinter C., Siccardi A.G., Clivio A., Dierich M.P. Efficient destruction of human immunodeficiency virus in human serum by inhibiting the protective action of complement factor H and decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) J. Exp. Med. 1996;183(1):307–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoiber H., Clivio A., Dierich M.P. Role of complement in HIV infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan B.L., Takefman D.M., Spear G.T. Complement canHIV-1 plasma virus by a C5-independent mechanism. Virology. 1998;248(2):173–181. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuo H., Ono N., Tanaka K., Yanagi Y. SLAM (CDw150) is a cellular receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2000;406(6798):893–897. doi: 10.1038/35022579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thielens N.M., Tacnet-Delorme P., Arlaud G.J. Interaction of C1q and mannan-binding lectin with viruses. Immunobiology. 2002;205(4–5):563–574. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugizov S.M., Berline J.W., Palefsky J.M. Epstein–Barr virus infection of polarized tongue and nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Nat. Med. 2003;9(3):307–314. doi: 10.1038/nm830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Walle G.R., Favoreel H.W., Nauwynck H.J., Pensaert M.B. Antibody-induced internalization of viral glycoproteins and gE-gI Fc receptor activity protect pseudorabies virus-infected monocytes from efficient complement-mediated lysis. J. Gen. Virol. 2003;84(Pt 4):939–948. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasantha S., Coelingh K.L., Murphy B.R., Dourmashkin R.R., Hammer C.H., Frank M.M., Fries L.F. Interactions of a nonneutralizing IgM antibody and complement in parainfluenza virus neutralization. Virology. 1988;167(2):433–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakimoto H., Johnson P.R., Knipe D.M., Chiocca E.A. Effects of innate immunity on herpes simplex virus and its ability to kill tumor cells. Gene Ther. 2003;10(11):983–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walport M.J. Complement. First of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(14):1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.S. Current status and prospects of studies on human genetic alleles associated with hepatitis B virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003;9(4):641–644. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkadis I.K., Mastellos D., Lambris J.D. Phylogenetic aspects of the complement system. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2001;25(8–9):745–762. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(01)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]