Highlights

-

•

We review PRRSV infectious clones and their applications.

-

•

14 infectious clones are available so far for genotypes I and II.

-

•

Genomic mutations, insertions, deletions, and replacements are successful.

-

•

We discuss advances and utilization of PRRSV reverse genetics and future potential.

Keywords: Arterivirus, PRRSV, Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, Infectious clones, Reverse genetics, Genetic manipulation

Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is endemic in most pig producing countries worldwide and causes enormous economic losses to the pork industry. Infectious clones for PRRSV have been constructed, and so far at least 14 different infectious clones are available representing both genotypes I and II. Two strategies have been taken for progeny reconstitution: RNA transfection and DNA transfection. Mutations, insertions, deletions, and replacements of the viral genome have been employed to study the structure function relationship, foreign gene expression, functional complementation, and virulence determinants. Essential regions and non-essential regions for viral replication have been identified in both the coding regions and non-encoding regions. Foreign sequences have successfully been inserted into the nsp2 and N regions and in the space between ORF1b and ORF2a. Chimeras between member viruses in the family Arteriviridae have also been constructed and utilized to study cell tropism and functional complementation. This review discusses the advances and utilization of PRRSV reverse genetics and its potential for future research.

1. Introduction

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) was first reported in the United States in 1987 and subsequently in Europe in 1990 and quickly became endemic in most pig producing countries worldwide (Benfield et al., 1992, Chand et al., 2012, Murakami et al., 1994, Shimizu et al., 1994, Wensvoort et al., 1991). The clinical manifestation of PRRS is complicated but is characterized by severe reproductive losses including abortions, mummified fetuses, weak born and stillborn young, post-weaning pneumonia, increased mortality, and growth retardation of young pigs. The etiological agent is PRRS virus (PRRSV). PRRSV belongs to the family Arteriviridae together with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) of mice, equine arteritis virus (EAV), and simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV). By comparative genome sequence analysis, PRRSV isolates are divided into two distinct genotypes: the European type (genotype I) and North American type (genotype II), represented by Lelystad virus (LV) and VR-2332 as the prototype virus for each genotype, respectively (Benfield et al., 1992, Wensvoort et al., 1991). The sequence similarities between two genotypes are approximately 60% (Allende et al., 1999, Nelsen et al., 1999, Wootton et al., 2000). Amino acid (aa) sequence alignments indicate that the major differences between two genotypes exist in the open reading frame (ORF) 1a region and the structural protein region (Kapur et al., 1996, Murtaugh et al., 1995, Nelsen et al., 1999). Natural deletions and insertions are observed in some isolates, especially in the ORF1a region (Fang et al., 2004, Gao et al., 2004, Shen et al., 2000, Tian et al., 2007).

The reverse genetics system has been developed for many RNA viruses, and infectious clones have been utilized for the study of biology and the vaccinology of viruses. The availability of such a powerful molecular tool has revolutionized the structure function studies for viral genome and proteins and has facilitated the studies for virulence, pathogenesis, immune responses, and vaccine development. The first full-length genomic cDNA clone was constructed for poliovirus more than three decades ago and its infectivity was demonstrated (Racaniello and Baltimore, 1981). Infectious clones have since been constructed for picornaviruses, caliciviruses, flaviviruses, togaviruses, influenza viruses, paramyxoviruses, rhabdoviruses, and coronaviruses to name a few (Almazan et al., 2000, Boyer and Haenni, 1994, Pu et al., 2011, Scobey et al., 2013, Sosnovtsev and Green, 1995, Yount et al., 2003). For arteriviruses, EAV and PRRSV are the first for which the reverse genetics system has been developed (Meulenberg et al., 1998, van Dinten et al., 1997). This review will summarize our current knowledge on the principles of PRRSV infectious clones and the application to the study of arteriviruses.

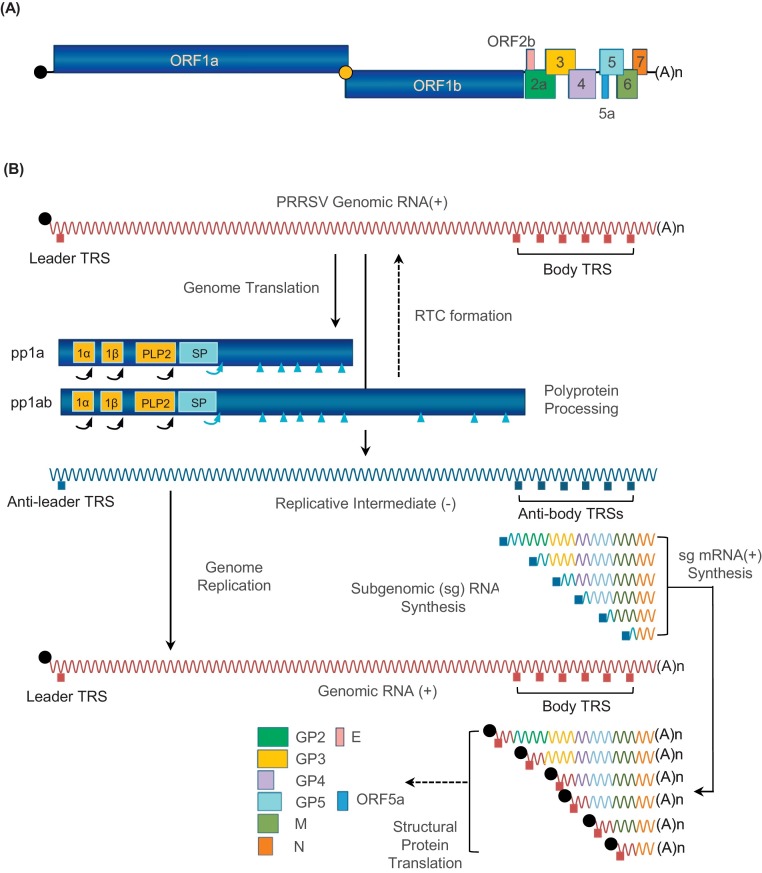

2. Genome structure of PRRSV and subgenomic mRNA production

The PRRSV genome is a single-strand positive-sense RNA of 15 Kb in length with a 5′ cap and 3′-polyadenylated tail (Fig. 1 A) (Meulenberg et al., 1993, Murtaugh et al., 1995, Nelsen et al., 1999, Wootton et al., 2000). The PRRSV genome is polycistronic and harbors two large open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, followed by ORF2a, ORF2b, and ORFs 3 through 7, plus ORF5a within ORF5 (Firth et al., 2011, Johnson et al., 2011, Meulenberg et al., 1993, Murtaugh et al., 1995, Nelsen et al., 1999, Wootton et al., 2000). A -2 ribosomal frame-shifting has recently been identified for expression of nsp2TF in the nsp2-coding region. The nsp2TF coding sequence is conserved in PRRSV, LDV, and SHFV but absent in EAV (Fang et al., 2012). The coding sequences in the viral genome are flanked by the 5′ and 3′ un-translated regions (UTRs) involved in translation, replication, and transcription (see review in Snijder et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Transcription and translation of PRRSV genome. (A) PRRSV genome organization. PRRSV possesses a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome of 15 kb in length with a 3′-polyadenylated tail and the 5′-cap (gray). The viral genome is polycistronic, harboring ORF1a and ORF1b, and structural genes of ORF2a, ORF2b, and ORFs 3 through 7, plus ORF5a within ORF5. (B) Viral gene expression. Non-structural proteins (black) are produced from pp1a and pp1ab after proteolytic processing. The PRRSV replicase-processing scheme involves the rapid auto-proteolytic release of nsp1α, nsp1β, and nsp2 (yellow boxes), mediated by papain-like proteinase (PLP) domains residing in each of them. The remaining polyproteins are processed by nsp4, resulting in a set of 14 individual nsps. The cleavage sites by PLPs and nsp4 are annotated by curved arrows and blue triangles, respectively. Structural proteins (color-coded) are expressed from the subset of sg mRNA. The 3′-co-terminal nested set of minus-strand RNAs is produced as a template for plus-strand sg mRNA synthesis. TRS, transcription regulatory sequence. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

ORF1a and ORF1b code for two large polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, with the expression of the latter mediated by the -1 frame-shifting in the ORF1a/ORF1b overlapping region (Fig. 1B; den Boon et al., 1991, Snijder and Meulenberg, 1998). Thus, the pp1b portion is expressed always as a fusion with pp1a. The pp1a and pp1ab proteins are further processed to generate 14 non-structural proteins (nsps). The polyprotein processing scheme involves the rapid auto-proteolytic release of three N-terminal nsps, nsp1α, nsp1β, and nsp2, mediated by papain like proteinase (PLP) residing in each of them. The subsequent processing for the remaining portion of polyproteins is mediated by the serine protease in nsp4 resulting in 14 individual nsps (den Boon et al., 1995, van Aken et al., 2006, Ziebuhr et al., 2000). The proteolytic cleavages for individual nsps were initially predicted by sequence comparisons in combination with some experimental data from EAV, the prototype virus of the family Arteriviridae (Fang and Snijder, 2010, Ziebuhr et al., 2000). The exact cleavage sites for PRRSV nsp1α↓nsp1β and nsp1β↓nsp2 have recently been confirmed to be M180↓A181 and G383↓A384 mediated by PRRSV-PLP1α and PRRSV-PLP1β, respectively (Chen et al., 2010a, Sun et al., 2009, Xue et al., 2010).

A set of 3′-coterminal nested subgenomic (sg) mRNAs, from which structural proteins are translated, is produced during infection (Fig. 1B). Each mRNA contains a common 5′-end leader sequence identical to the 5′-proximal part of the genome and this sequence is referred to as transcription-regulatory sequence (TRS). The fusion of the common 5′ sequence (leader TRS) to the different 3′-body segments of sg mRNAs is mediated by discontinuous transcription which is a common strategy of nidoviruses (Sawicki et al., 2007, Snijder et al., 2013, Sola et al., 2011). During the negative-strand sg RNA synthesis, transcription is attenuated at different body TRS regions of the genomic template. The nascent subgenome-length minus-strand RNA, having an anti-body TRS at its 3′ end, will then move and base-pair with the leader TRS and completes the extension of sg RNA. Minus-strand sg RNAs subsequently serve as a template for plus-strand sg mRNA which is subsequently translated for structural protein (Music and Gagnon, 2010, Sawicki et al., 2007, Snijder et al., 2013).

3. Construction of PRRSV infectious clones

The genome of negative-strand RNA viruses is non-infectious, and its replication in permissive cells requires the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex as the infectious unit. In contrast, the genome from positive-strand RNA viruses is fully infectious, and thus the assemly of full-length cDNA clones corresponding to the RNA genome is the kernel to the construction of infectious clones (Boyer and Haenni, 1994, Meyers et al., 1997, Moormann et al., 1996, Sosnovtsev and Green, 1995, van Dinten et al., 1997). Non-retroviral RNA viruses do not undergo a DNA intermediate step in their replication cycle. To obtain a template which can be manipulated by molecular techniques, a full-length cDNA clone is first generated using the reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase. Once generated, two strategies have been established to generate virus progeny from the full-length copy of viral genome: RNA transfection and DNA transfection. In the RNA transfection strategy, viral RNA is synthesized by in vitro transcription using T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase coupled with the respective promoter located immediately upstream of the viral genome. The synthesized RNA genome is then introduced into cells to initiate an infection cycle. In the DNA launch strategy, a full-length genomic clone is placed under a eukaryotic promoter such as a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and the entire plasmid is introduced to cells for transcription by exploiting the nuclear function of the cell. The transcribed viral genome in the nucleus is exported to the cytoplasm where viral genome translation and replication occur. This strategy omits the steps of in vitro synthesis of genomic RNA and RNA transfection, thus the risk of RNA degradation during transfection is reduced and transfection efficiency becomes consistent (Yoo et al., 2004).

An arterivirus infectious clone was first made for EAV. The pEAV030 full-length clone containing the 12.7 kb cDNA copy of the EAV genome was infectious (van Dinten et al., 1997), and the first PRRSV infectious clone pABV437 was developed for the genotype I PRRSV Lelystad virus (Meulenberg et al., 1998). Subsequently, infectious clones for VR-2332 which is the genotype II PRRSV, and the European-like genotype I PRRSV SD01-08 circulating in the US was developed (Fang et al., 2006a, Fang et al., 2006b, Nielsen et al., 2003). Numerous clones have additionally been developed including the highly-pathogenic PRRSV that emerged in China in 2006 (Guo et al., 2013, Lv et al., 2008, Zhou et al., 2009). To date, at least 14 different infectious clones are available for PRRSV (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Construction of PRRSV infectious clone.

| Name | Yeara | Genotypeb | Isolate | GenBank # | Cell type for |

Vector | Promoter | Genetic markerd | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfection | Passage | |||||||||

| pABV414e | 1998 | I | Ter Huurne (TH) | N/A | BHK-21 | PAM/CL2621 | pOK12 | T7 | N/A | Meulenberg et al. (1998) |

| pABV416e | 1998 | I | Ter Huurne (TH) | N/A | BHK-21 | PAM/CL2621 | pOK12 | T7 | N/A | Meulenberg et al. (1998) |

| pABV437 | 1998 | I | Ter Huurne (TH) | N/A | BHK-21 | PAM/CL2621 | pOK12 | T7 | pacI(3′UTR) | Meulenberg et al. (1998) |

| N/A | 2003 | II | VR-2332 | AY150564 | BHK-21C | PAM/MARC-145 | pOK12 | T7 | BstZ17I (ORF1a)/HpaI(3′UTR) | Nielsen et al. (2003) |

| pFL12 | 2004 | II | NVSL#97-7895 | AY545985 | MARC-145 | PAM/MARC-145 | pBR322 | T7 | BsrGI(ORF1a) | Truong et al. (2004) |

| pT7-P129 | 2005 | II | P129 | AF494042 | MARC-145 | MARC-145 | pCR2.1 | T7 | C1559T/A12622G | Lee et al. (2005) |

| pCMV-S-P129 | 2005 | II | P129 | AF494042 | MARC-145 | MARC-145 | pCMV | hCMV | C1559T/A12622G | Lee et al. (2005) |

| pSD01-08 | 2006 | NA If | SD 01-08 (P34) | DQ489311 | BHK-21 | PAM/MARC-145 | pACYC177 | T7 | ScaI(ORF7) | Fang et al., 2006a, Fang et al., 2006b |

| pPP18 | 2006 | II | Prime Pac (PP) | DQ779791 | MARC-145 | PAM/MARC-145 | pOK12 | T7 | SpeI(ORF1a) | Kwon et al. (2006) |

| pVR-V7 | 2007 | II | VR2332 | DQ217415 | MA-104/MARC-145 | MA-104/MARC-145 | pOK12HDV-PacI | T7 | G7329A/T7554C | Han et al. (2007) |

| pWSK-DCBA | 2007 | II | BJ-4 | EU360128 | MARC-145 | PAM/MARC-145 | pWSK29 | SP6 | VspI(ORF1b) | Ran et al. (2008) |

| pAPRRS | 2008 | II | APRRS | N/A | MA-104 | MA-104 | pBluescript SK(+) | T7 | N/A | Yuan and Wei (2008) |

| pORF5M | 2008 | II | APRRS | N/A | MA-104 | MA-104 | pBluescript SK(+) | T7 | MluI (ORF5) | Yuan and Wei (2008) |

| pJX143 | 2008 | II | JX143 | EF488048 | MA-104 | MA-104 | pBlueScript II SK (+) | T7 | N/A | Lv et al. (2008) |

| pJX143M | 2008 | II | JX143 | N/A | MA-104 | MA-104 | pBlueScript II SK (+) | T7 | MluI (ORF6) | Lv et al. (2008) |

| pWSK-JXwn | 2009 | II | JXwn06 | N/A | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pWSK29 | SP6 | BstBI(ORF1a) | Zhou et al. (2009) |

| pWSKHB-1/3.9 | 2009 | II | HB-1/3.9 | N/A | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pWSK29M | SP6 | MluI (ORF1a) SifI (ORF1b) |

Zhou et al. (2009) |

| pHuN4-F112 | 2011 | II | HuN4-F112 | N/A | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pBlueScript II SK (+) | SP6 | MluI (ORF6) | Zhang et al. (2011) |

| pACYC-VR2385-CA | 2011 | II | VR2385-CA | N/A | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pACYC177 | T7 | Sph I(ORF1a) | Ni et al. (2011) |

| pIR-VR2385-CA | 2011 | II | VR2385-CA | N/A | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pIRES-EGFP2 | CMV | Sph I(ORF1a) | Ni et al. (2011) |

| pSHE | 2013 | I | SHE(AMER-VAC-PRRS/A3) | GQ461593 | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pB-ZJS | CMV | N/A | Gao et al. (2013) |

| pCMV-SD95-21 | 2013 | II | SD95-21 | KC469618 | BHK-21 | MARC-145 | pACYC177 | CMV | N/A | Li et al. (2013) |

N/A, not application.

The individual time of PRRSV infectious clones construction referred to the date of each publication.

Genotype I and II PRRSV represents European and North America strains, respectively.

c Sequences of full-genome cDNA clone rather than complete genome sequences of parental virus are listed.

The genome area in which the restricted enzyme sites are introduced is indicated with brackets. The position where single mutations are introduced is given.

Genome-length cDNA clones of pABV414 and pABV416 encode identical viral protein sequences except for one amino acid at position 1084 in ORF1a, which are a Pro in pABV414 and a Leu in pABV416.

The abbreviation, NA I, in the genotype column represents genotype I PRRSV isolated in North America.

PRRSV infectious clones have mostly been developed based on the RNA launch strategy. BHK-21, MA-104, and MARC-145 cells are cells of choice for transfection and progeny production. Although BHK-21 cells are non-permissive for PRRSV infection, they provide a high efficiency of transfection and a good production of progeny (Meulenberg et al., 1998). To eliminate the need for in vitro transcription and consistency associated with RNA transfection, the CMV promoter has been used for construction of the P129 infectious clone. The P129 virus is an isolate recovered from an outbreak of highly virulent atypical PRRS in the mid-Western USA in 1995 (Lee et al., 2005, Yoo et al., 2004). The CMV promoter-based infectious clone is convenient and simple to use and provides a consistency of transfection and recovery of progeny virus (Lee et al., 2005).

An infectious clone should genetically be identical to the parental virus. However, non-viral nucleotides are occasionally added to the viral genome at the 5′ or 3′ end to meet the engineering needs without impeding the infectivity of the clones (Meulenberg et al., 1998, Truong et al., 2004). To differentiate the reconstituted progeny virus from the parental virus, genetic markers of either restricted enzyme recognition sequences or certain nucleotide mutations have been introduced to infectious clones, and such modifications should be non-lethal and stable. To assure the starting position of the RNA polymerase II-mediated transcription, 24 nucleotides are placed between the TATA box and the genome start when constructing pCMV-S-P129 (Lee et al., 2005). The PRRSV genome is usually divided to several fragments flanked by restriction sites for subsequent assembly (Meulenberg et al., 1998, Nielsen et al., 2003). As a cloning vector, a low-copy-number plasmid is generally preferred as suggested in some studies (Meulenberg et al., 1998, Sumiyoshi et al., 1992, Nielsen et al., 2003) but has appeared unnecessary. Progeny virus generated from an infectious clone should ideally retain the biological properties of the parental virus, such as growth rate, virulence, and transmissibility (Kwon et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2005, Meulenberg et al., 1998, Nielsen et al., 2003, Truong et al., 2004, Yuan and Wei, 2008).

4. Engineering PRRSV infectious clones

Like most RNA viruses, PRRSV genome has evolved to optimal fitness, and most of the genetic information seems to be essential (Verheije et al., 2001). Notably, the 3′-proximal portion of the genome is compact and organized to contain eight genes, most of which overlap with neighboring genes (Snijder et al., 2013). The PRRSV genome is complex and the engineering of such a compact viral genome is a challenge. In addition, minor alternations in conserved regions or functional domains in the genome almost inevitably lead to non-viable consequences (Ansari et al., 2006, Kroese et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2005). Despite such difficulties, some genetic manipulations for PRRSV have been successful.

4.1. Strategies for infectious clone engineering

Mutation, deletion, insertion, and substitution are major approaches to viral genome manipulation. Due to the large genome of PRRSV, shuttle plasmids have been used as an intermediate platform to contain the target viral genomic sequence with a pair of unique enzyme sites at each end. Mutations are introduced to target sites or sequences in the shuttle plasmid. The biological functions of PLP1α and PLP1β in nsp1, conserved cysteine residues at C49 and C54 in the E protein, N-linked glycosylation sites in GP3 at N131 and GP5 at N34, N44, and N51, cysteines at C23, C75, and C90 for homo-dimerization of N protein, and the motif for nuclear localization signal (NLS) of N have been mutated to produce PRRSV mutants (Ansari et al., 2006, Kroese et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2006, Lee and Yoo, 2005, Pei et al., 2009, Vu et al., 2011). Alanine scanning and protein surface accessibility predictions were conducted for identification of residues for type I IFNs or TNF-α antagonism of nsp1, and specific residues have been mutated in the infectious clones (Beura et al., 2012, Li et al., 2013, Subramaniam et al., 2012). Mutations have also been introduced to knockout genes by changing the translation initiation codon, and this approach destroys the expression of nsp1 and E protein (Lee and Yoo, 2006, Tijms et al., 2001).

Deletion of genomic sequences has been applied to identifying non-essential regions for PRRSV replication or to obtaining attenuated live vaccine candidates (Verheije et al., 2001). Inter-genotypic sequence alignments between genotype 1 and genotype 2 reveal the regions of sequence heterogeneity suggesting the potential to tolerate the deletions, and non-essential regions in the N gene and 3′-UTR (Table 2 ; Sun et al., 2010b, Tan et al., 2011). The hypervariable regions have been observed in the nsp2 gene (Fang et al., 2004, Gao et al., 2004, Ni et al., 2013, Shen et al., 2000, Tian et al., 2007), suggesting the existence of a non-essential region in nsp2 (Chen et al., 2010b, Han et al., 2007, Ran et al., 2008, Xu et al., 2012b). Deletion of ORF2 or ORF4 results in the absence of infectivity, suggesting the requirement of GP2 and GP4 proteins for PRRSV infectivity (Welch et al., 2004).

Table 2.

Identification of non-essential regions of PRRSV genome.

| Genotype and gene | Mutation/deletion (nts or aa) | Motif | Infectious clone | Growthd | GenBank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II | 5′UTR | 1–3 nts | N/A | pAPRRS | N/A | GQ330474.2 |

| II | nsp2 | 13–35 aa | hypervariable | pVR-V7 | ↓ | DQ217415 |

| II | nsp2 | 324–726 aa | hypervariable | pVR-V7 | ↓ | DQ217415 |

| II | nsp2 | 727–813 aa | hypervariable | pVR-V7 | ↓ | DQ217415 |

| II | nsp2 | 480–667 aa | hypervariable | pHuN4-F112 | N/A | EF635006 |

| I | nsp2 | 691–722 aa | ES3a | pSD01-08 | ↑ | DQ489311 |

| I | nsp2 | 736–790 aa | ES4a | pSD01-08 | nc | DQ489311 |

| I | nsp2 | 1015–1040 aa | ES7a | pSD01-08 | ↓ | DQ489311 |

| II | ORF7 | 5–13 aa | N/A | pAPRRS | ↓ | GQ330474.2 |

| II | ORF7 | 39–42 aa | N/A | pAPRRS | ↓ | GQ330474.2 |

| II | ORF7 | 48–52 aa | N/A | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 |

| II | ORF7 | 120–123 aa | N/A | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 |

| II | ORF7 | 43,44 aa | NLSb | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 |

| II | ORF7 | 43,44,46 aa | NLSb | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 |

| II | ORF7 | 46,47 aa | NLSb | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 |

| I | ORF7 | 123–128 aa | N/A | pABV437 | nc | N/A |

| I | 3′UTR | 14989–14995 nts | N/A | pABV437 | nc | N/A |

| II | 3′UTR | 15370–15409 nts | N/A | pAPRRS | N/A | GQ330474.2 |

N/A, not application. “nc” stands for no change.

The abbreviation, ES, stands for the immunodominant B-cell epitopes identified in type I PRRSV.ES2-ES7 are identified in nsp2 encoding regions (Oleksiewicz et al., 2001).

NLS stands for the nuclear localization signal which mediates the nuclear localization of PRRSV N protein.

c Ref. Seq. is the abbreviation of reference sequence, and GenBank accession numbers for each construct are provided.

Symbols “↑” and “↓” indicate increased or reduced virus growth respectively.

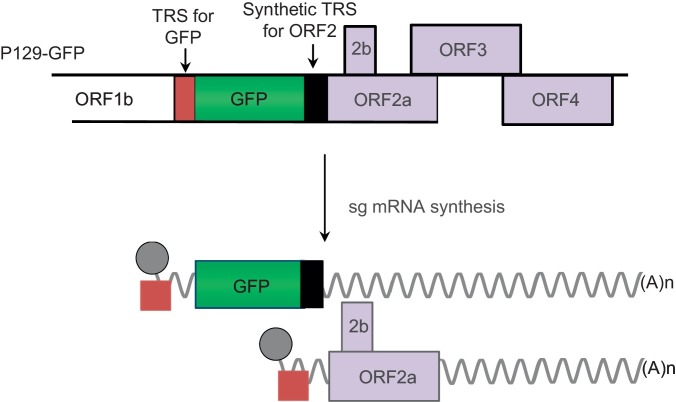

Insertion of additional nucleotides to the viral genome expands the scope of modifications. An attempt was made to separate overlapping regions of PRRSV structural protein genes, and three restriction enzyme sites were inserted between ORFs 5/6 and ORFs 6/7 (Yu et al., 2009), which produced viable viruses. The possibility of expressing foreign genes using PRRSV has been explored; the nsp2 gene was utilized as an insertion site for expressions of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and FLAG tag (Fang et al., 2006b, Kim et al., 2007). An alternate approach was taken to insert foreign genes within a structural gene; for example, a small portion of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) gene into the 5′ or 3′ end of ORF7 of PRRSV (Bramel-Verheije et al., 2000). However, the insertion of HA to N gene resulted in a nonviable virus. A strategy utilizing the mechanism of transcription of PRRSV for foreign gene expression is of particular interest. Using an infectious clone, two unique enzyme sites have been introduced between ORF1b and ORF2, and a copy of the TRS6 sequence was inserted to replace the TRS designed to synthesize the mRNA for foreign gene expression (Fig. 4) (Lee et al., 2005, Pei et al., 2009, Yoo et al., 2004). The foreign genes including GFP, capsid protein of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2), Discosoma sp. (sea anemone) red fluorescent protein (DsRED), Renilla luciferase (Rluc), IFN-α1, IFN-β, IFN-δ3, and IFN-ω5 have all been expressed as an independent transcript using this approach (Table 3 ; Pei et al., 2009, Sang et al., 2012).

Fig. 4.

PRRSV infectious clone for foreign gene expression. A copy of TRS (Black bar) is inserted between ORF1b and ORF2. Two kinds of sg mRNAs are produced from this construction. The GFP or other foreign genes is inserted between the synthetic TRS (Black bar) and the original TRS (Brown bar), and the original TRS leads to generation of mRNA for GFP expression. The inserted TRS drives the synthesis of sg mRNA for ORF2 expression. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Table 3.

Insertion tolerable regions in PRRSV genome.

| Genotype | Genomic region | Position |

Foreign sequence | Infectious clone | Growth ratea | GenBank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nt | aa | |||||||

| II | ORF1a | nsp2 | 3219/3220 | N/A | GFP | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 |

| II | ORF1a | nsp2 | 3219/3220 | N/A | FLAG-tag | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 |

| II | ORF1a | nsp2 | 3614/3615 | N/A | GFP | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 |

| I | ORF1a | nsp2 | N/A | 348/349 | GFP | pSD01-08 | ↓ | DQ489311 |

| II | ORF1a | nsp2 | N/A | 507/508 | B-cell epitope in NDV NP | pSK-F112-D508–532 | nc | N/A |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | TRS6 + GFP | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | TRS6 + PCV2 C | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | TRS6 + DsRED | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | TRS6 + Rluc | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | IFNα1 | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | IFNβ | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | IFNδ3 | pCMV-S-P129 | nc | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | IFNω5 | pCMV-S-P129 | ↓ | AF494042 | |

| II | ORF1b/ORF2 | N/A | N/A | AscI,SwaI, PacI | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 | |

| II | ORF4/ORF5 | N/A | N/A | NdeI | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 | |

| II | ORF5/ORF6 | N/A | N/A | AscI,SwaI, PacI | pAPRRS | ↓ | GQ330474.2 | |

| II | ORF6/ORF7 | N/A | N/A | AscI,SwaI, PacI | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 | |

| II | ORF7/3′UTR | N/A | N/A | NdeI | pAPRRS | nc | GQ330474.2 | |

N/A, not application; nc, no change.

Symbols “↑” and “↓” indicate increased or reduced virus growth respectively.

Multiple genes, a single gene, or partial sequence of the viral genome have been substituted with corresponding sequences from other arteriviruses for chimeric arterivirus construction. The first chimeric arterivirus was generated using an EAV infectious clone as a backbone, and ectodomains of two membrane proteins, GP5 and M, were substituted with the corresponding sequences from PRRSV or LDV (Dobbe et al., 2001). These chimeric viruses were viable, and additional chimeric arteriviruses have been constructed (Table 4 ). The construction of intra- or inter-genotypic PRRSV chimeras is maneuverable, and the regions of 5′-UTR, non-structural genes, and structural genes have been replaced (Gao et al., 2013, Lu et al., 2012, Tian et al., 2011, Tian et al., 2012, Vu et al., 2011, Zhou et al., 2009). To facilitate the intra-genotypic substitution, a gene-swapping mutagenesis technique has been used to substitute the structural genes (Kim and Yoon, 2008). Using this technique, individual replacement of ORF2a and ORF2 through ORF6 of VR-2332 was successfully carried out with corresponding ORFs from other strains of PRRSV including JA142, SDSU73, PRRS124, and 2M11715 (Kim and Yoon, 2008).

Table 4.

Constructions of chimeric viruses.

| Swapped regiona |

Substituentb |

Viability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | Strain | Infectious clonec | Genome region | Position aa | Virus | Strain | Genome region | Position aa | |

| EAV | Bucyrus | pA45 | ORF5 | 1–114 | LDV | P | GP5 | 1–64 | + |

| PRRSV | IAF-Klop | GP5 | 1–64 | + | |||||

| SHFV | LVR 42–0/M6941 | GP7 | 1–138 | − | |||||

| SinV | San Juan | E1 | 1–428 | − | |||||

| VSV | HR | G | 1–402 | − | |||||

| Whole | EAV | A45-80.4 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||

| 5rUCD | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5r6D10 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rVAC | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rKY84 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rIL93 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rCA95 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rWA97 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5rATCC | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 5r10B4 | GP5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| ORF6 | 17–162 | PRRSV | IAF-Klop | M | 1–16 | − | |||

| LDV | P | M | 1–14 | − | |||||

| ARVAC | prMLVB4/5 | ORF5 | 115–255 | PRRSV | IA-1107 | ORF5 | 1–64 | + | |

| prMLVB4/5 | ORF5 | N/Ad | PRRSV | IA-1107 | ORF5 | Whole | − | ||

| prMLVB5/6 | ORF6 | N/Ad | PRRSV | IA-1107 | ORF6 | Whole | − | ||

| prMLVB4/5/6 | ORF6 | 17–162 | PRRSV | IA-1107 | ORF6 | 1–17 | + | ||

| PRRSV | LV | pABV437 | ORF6 | 1–16 | PRRSV | V2332 | M | 1–16 | − |

| LDV | P | M | 1–14 | + | |||||

| EAV | Bucyrus | M | 1–17 | − | |||||

| pABV871 | ORF6 | 1–16 | PRRSV | V2332 | M | 1–16 | + | ||

| EAV | Bucyrus | M | 1–17 | + | |||||

| VR2332 | N/A | ORF2 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF2 | Whole | + | |

| ORF3 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF3 | Whole | + | |||

| 1–194 | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF3 | 1–194 | + | ||||

| 183–255 | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF3 | 183–255 | + | ||||

| ORF4 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF4 | Whole | + | |||

| ORF5 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF5 | Whole | + | |||

| SDSU73 | ORF5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| 2M11715 | ORF5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| PRRS124 | ORF5 | Whole | + | ||||||

| ORF6 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORF6 | Whole | + | |||

| ORFs5-6 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORFs5-6 | Whole | + | |||

| ORFs4-6 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORFs4-6 | Whole | + | |||

| ORFs3-6 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORFs3-6 | Whole | + | |||

| ORFs2-6 | Whole | PRRSV | JA142 | ORFs2-6 | Whole | + | |||

| APRRS | pAPRRS asc |

ORFs2a-4 | Whole | PRRSV | SHE | ORFs2a-4 | Whole | + | |

| EAV | vEAV030 | ORFs2a-4 | Whole | + | |||||

| ORFs2a-5 | Whole | PRRSV | SHE | ORFs2a-5 | Whole | + | |||

| ORF5 | Whole | PRRSV | SHE | ORF5 | Whole | + | |||

| NVSL# 97–7895 | FL12 | ORFs2a-7 | Whole | PRRSV | PRRSV01 | ORFs2a-7 | Whole | + | |

N/A, not application. Whole represents the full sequence of a specific region.

This section provides information of the regions replaced by the counterparts, including the virus, virus strains, the infectious clone used for swapping, and the exact position in which region is changed.

The substituent section indicates the sequences used for substitutions.

Infectious clone construct provided here includes both prototypes and modified constructs.

4.2. Identification of modification-limited genomic regions

4.2.1. nsp2

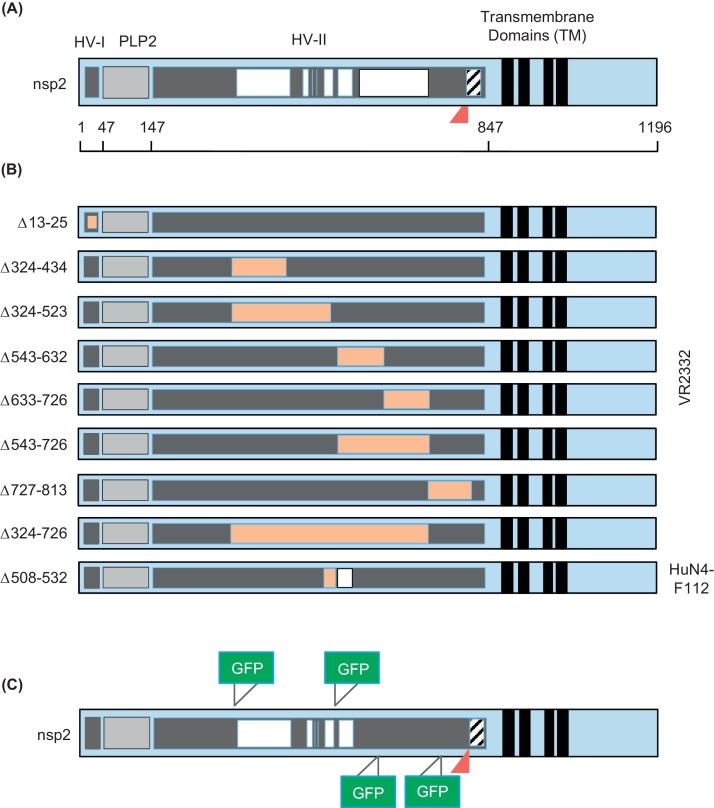

PRRSV nsp2 is a multifunctional protein that undergoes remarkable genetic variations. The nsp2 protein consists of five regions: hypervariable region I (HV-I), PLP2 cysteine protease core, hypervariable region II (HV-II), transmembrane regions, and a C-terminal tail (Fig. 2 A; Han et al., 2009). The PLP2 cysteine protease domain possesses cis-acting and trans-acting cleavage activities and mediates its rapid release from pp1a and pp1ab (Han et al., 2009, Snijder et al., 1995). Two sites were initially predicted for nsp2/nsp3 cleavage at 981G/982G and somewhere at 1196G/1197G/1198G, and recent studies showed the actual cleavage occurs at 1196G/1197G for VR-2332 (Allende et al., 1999, Han et al., 2009, Nelsen et al., 1999). The corresponding cleavage for EuroPRRSV SD01-08 likely occurs at 1445GG/1447A (Fang and Snijder, 2010). PLP2 is as a member of the ovarian tumor domain (OTU) family of deubiquitinating enzymes, and has shown to deconjugate ubiquitin (Ub) and IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) 15 from cellular targets. This is an important viral strategy inhibiting the Ub-dependent and ISG15-dependent host innate immune responses (Frias-Staheli et al., 2007, Sun et al., 2010a, Sun et al., 2012b, van Kasteren et al., 2012)

Fig. 2.

Engineering of infectious clones for nsp2 region. (A) Schematic presentation of the nsp2 protein. The nsp2 protein consists of five regions: hypervariable region I (HV-I), PLP2 cysteine protease core, hypervariable region II (HV-II), transmembrane regions, and the C-terminal tail. White areas indicate natural deletions. A triangle indicates the position of natural insertion. (B) Location of experimental sequence deletions (Orange). (C) Foreign gene insertion sites. Triangles indicate the position of insertion. GFP, green fluorescent protein; HV, hypervariable region; PLP, papain-like proteinase. Numbers indicate amino acid positions of nsp2. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Besides the proteinase and deubiquitinase functions, nsp2 contributes to the major genetic differences between genotypes I and II, sharing only less than 40% similarity at the amino acid level (Allende et al., 1999, Nelsen et al., 1999). The nsp2 gene also contains naturally inserted sequences and deletions (Fig. 2A) in the hypervariable region (Fang et al., 2004, Gao et al., 2004, Ni et al., 2011, Shen et al., 2000, Tian et al., 2007). The deletion of 12 amino acids in nsp2 was first found in a Chinese PRRSV isolate, HB-2(sh)/2002, in comparison with other North American isolates (Gao et al., 2004). Sequence analysis of PRRSV MN184 reveals three discontinuous deletions of 111, 1, and 19 amino acids at the corresponding positions 324–434, 486, and 505–523 of VR-2332, respectively (Han et al., 2006). Discontinuous deletions were also identified in the highly pathogenic PRRSV (HP-PRRSV) associated with the 2006 outbreaks of porcine high fever disease in China (Tian et al., 2007). The 30 amino acids discontinuous deletion consists of 1 aa deletion at position 482 and 29 aa deletions at 534–562, and the deletion region contains B-cell epitopes (de Lima et al., 2006) and T-cell epitopes (Chen et al., 2010b). Strikingly, cell culture passages of PRRSV may generate a deletion in nsp2, and a study shows the generation of a large deletion of 135 aa at 581–725 in nsp2 during passages (Ni et al., 2011). A deletion in nsp2 is also found in genotype I PRRSV. The EuroPRRS SD-01-08 virus in the US shows a 17 aa deletion at positions 349–365 of nsp2 when compared to Lelystad virus (Fang et al., 2004). Biological significance of the genetic deletion in nsp2 remains to be determined. Besides deletions, a 36 aa insertion was also observed in the SP strain of PRRSV, which is a vaccine strain, located between G812 and T849 of the SP nsp2 (Shen et al., 2000).

Given the tolerance of deletions and insertions in the hypervirable region of nsp2, this region is considered as a site for foreign gene insertion (Fig. 2B and C). The GFP gene was inserted into nsp2 of the SD01-08 strain and fully infectious virus was rescued (Fang et al., 2006b). The GFP insertion did not affect the growth of the virus, and the infectivity was comparable to that of parental virus. The capacity of deletion in nsp2 was determined by introducing a series of in-frame deletions (Han et al., 2007). The PLP2 domain, the PLP2 downstream flanking region, and the transmembrane domain were crucial for virus replication but deletions of 13–35 aa from the N-terminal portion of the hypervariable region and 324–813 aa from the hypervariable region appeared to be tolerable for viability. In the hypervariable region, the largest deletion that can be achieved was about 400 aa at positions 324–726, although a deletion of up to 200 aa is preferable for infectivity (Fig. 2B). The insertion of GFP or other genes such as New Castle disease virus nucleoprotein (NP) gene has been successful as long as insertions reside in the hypervirable regions (Fig. 2C) (Kim et al., 2007, Xu et al., 2012a). The deletion of inmmunodominant linear B-cell epitopes (ES2-ES7) were attempted; deletion of ES3, ES4, or ES7 allowed the generation of an infectious virus (Chen et al., 2010b, Oleksiewicz et al., 2001).

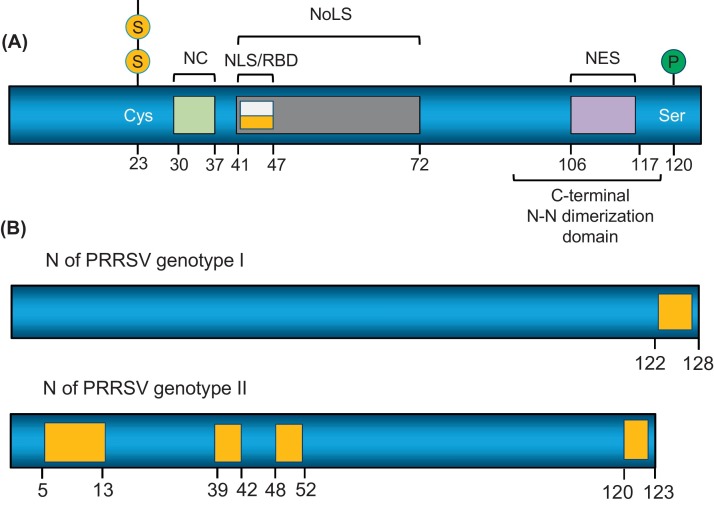

4.2.2. N protein

PRRSV N is a mutilfunctional protein. The specific domains and residues critical for virus replication have been identified in N (Fig. 3 A). The N protein is comprised of 123 or 128 aa for the North American and European genotypes, respectively (Music and Gagnon, 2010). N consists of the N-terminal RNA-binding domain (RBD) at positions 41–47 and the C-terminal dimerization domain comprising a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet floor flanked by α-helices (Doan and Dokland, 2003, Yoo et al., 2003). As the sole component of viral capsid, N interacts with itself via covalent or noncovalent interactions (Doan and Dokland, 2003, Wootton and Yoo, 2003). The cysteine at position 23 is responsible for the formation of an intermolecular disulfide bond, and aa 30–37 are essential for mediating noncovalent homodimers (Wootton and Yoo, 2003). A crystallographic study on N shows the imprtance of the C-terminal dimerization domain for N (Doan and Dokland, 2003, Spilman et al., 2009). PRRSV N is a serine phosphoprotein which is a common property for N of EAV and coronaviruses (Music and Gagnon, 2010, Wootton et al., 2002). One of the phosphorylation sites of N is at position 120, but its biological significance is still unknown. N contains NLS in a stretch of basic amino acids 41-PGKKNKK-47 which is overlapping with the RNA-binding domain and particially with a nucleolar localization signal (NoLS) at aa 41–72 (Rowland et al., 1999, Rowland et al., 2003). The nuclear export signal (NES) is found at positions 106–117 and is responsible for the nucleolar-cytoplasmic shuttling of N (Rowland and Yoo, 2003).

Fig. 3.

Engineering of infectious clones in N gene. (A) Schematic presentation of the nucleocapsid (N) protein. NLS and RBD overlap each other. (B) Deletion tolerance regions (yellow) in N protein. NLS, nuclear localization signal; NES, nuclear export signal; P, phosphorylation site; S, disulfide bridge, RBD, RNA-binding domain; NoLS, nucleolar localization signal. NCI, non-covalent interaction motif. Numbers indicate amino acid positions of N. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The functional structure of N is compact and thus N is sensitive to structural modification. The secondary structure in the C-terminal residues 112–123 is an important determinant for conformational epitopes, and the mutations in this region change the monoclonal antibody (MAb) reactivity (Wootton et al., 2001). Insertion of a foreign sequence into the N gene was attemped and the influenza virus HA epitope was added at the N-terminus or C-terminus. Despite the initial rescue of the infectious virus, the HA expression was unsuccessful (Bramel-Verheije et al., 2000). The GFP tag was inserted between ORF6 and ORF7 to moniter the ORF7 mRNA synthesis, but no mRNA was made, indicating the 5′ end of the ORF7 gene is essential for mRNA synthesis (Yoo et al., 2004). The N protein is inter-genotypically conserved but shares only 60% of its identity between LV and VR-2332 (Dea et al., 2000). The C-terminus of N is heterogenous, and truncation of up to 6 aa is tolerable (Verheije et al., 2001). In another study, deletions were made at the inter-genotypic variable region or conserved region of N, and 4 regions at 5–13, 39–42, 48–52, and 120–123, were found to be dispensible for viability (Fig. 3B) (Tan et al., 2011). No foreign gene can be incorporated in these rgions.

4.2.3. Non-conding regions

The PRRSV genome is flanked by 5′- and 3′-UTR, and the UTR sequences play a vital role for genomic replication, mRNA transcription, and protein translation (Pasternak et al., 2006, Snijder et al., 2013). The non-coding regions of the genome have been investigated. By serial deletions, the first 3 nucleotides in 5′-UTR appears to be dispensible for viability in type II PRRSV (Gao et al., 2012). For 3′-UTR, the first 11 nucleotides are unique for each genotype, and a stretch of 38 nucleotides is present in VR-2332 but is absent in LV (Allende et al., 1999, Verheije et al., 2001). A deletion study shows that 7 nucleotides at the 5′ end of the 3′-UTR is tolerable for genotype I PRRSV (Verheije et al., 2001). The 3′-UTR of genotype II has also been studied, and at least 40 nucleotides immediately following ORF7 is dispensable for virus viability (Sun et al., 2010b).

The genetic information on the structural region of arteriviruses is organized in an extremely efficient manner. The genes for GP2, GP3, and GP4 overlap each other, and similarly the genes for GP5, M, and N overlap each other for PRRSV. This structural complexicity hampers the genetic manipulation of infectious clones. The importance of the overlapping gene arrangement for the life-cycle of virus has been studied (Verheije et al., 2002, Yu et al., 2009). A series of full-length clones were engineered to separate overlapping genes for EAV ORFs 4/5 or ORFs 5/6 by inserting small additional sequences containing a termination codon for the upstream gene, a unique restriction site, and a translation initiation codon for the downstream gene. The insertions result in the functional separation of overlapping ORFs, and do not impair infectivity (de Vries et al., 2000). The ORFs 5/6 separation in genotype I PRRSV is also possible and progeny virus is produced (Verheije et al., 2002). For the North American PRRSV, restriction sites were inserted between ORFs 1/2, ORFs 4/5, ORFs 5/6, ORFs 6/7, and ORFs 7/3′-NTR, and progeny viruses are generated from these modifications. This indicates that gene overlap is dispensable for infectivity and that separation of each gene does not interrupt mRNA synthesis (Yu et al., 2009).

5. Applications of PRRSV infectious clone

5.1. Chimeric viruses and cell tropism

The development of infectious clones allows the construction of chimeric arteriviruses. An attempt was made to swab the ectodomains of GP5 and M. In engineered chimeric viruses using the EAV clone as a backbone, the ectodomains were replaced by corresponding sequences from other arteriviruses. Chimeric viruses containing the GP5 ectodomain from LDV and PRRSV were infectious. These chimeric viruses however retain their cell tropism for BHK-21 cells, which are susceptible for EAV but non-susceptible for LDV and PRRSV (Dobbe et al., 2001). Replacement of the M ectodomain of EAV with the corresponding sequence from other arteriviruses does not produce infectious virus, but replacement of the M ectodomain of PRRSV with the corresponding sequence from LDV, EAV, and genotype II PRRSV produced an infectious virus. Using the LV infectious clone as a backbone, substitutions with the EAV M ectodomain or VR-2332M ectodomain is impossible, but removal of the gene overlap between the M and GP5 genes is required before swapping, indicating that the VR-2332M ectodomain and EAV M ectodomain are incompatible with the remaining part of LV M. It is also possible that unintended mutations may have been introduced to GP5 during the ectodomain swap (Verheije et al., 2002). Substitution of structural genes between arteriviruses has been extremely useful to identify viral factors for viral tropism. The substitution of GP5 or/and M do not alter their cell tropism (Dobbe et al., 2001, Lu et al., 2012, Verheije et al., 2002). In contrast, the substitution of minor envelope proteins and E protein using the PRRSV infectious clone as a backbone allows the chimeric PRRSV to acquire a broad cell tropism but to lose the ability to infect PAMs. It indicates that the GP2/GP3/GP4 minor proteins are determinants for cell entry and tropism (Tian et al., 2011).

5.2. Chimeric viruses and virulence immunogenicity

Intra-genotypic or inter-genotypic gene-swapping have been conducted between EAV and PRRSV to study the genetic compatibility and viral-specific phenotypes, including neutralization, virulence, and pathogenesis. For neutralization, 9 chimeric EAVs were generated in which each construct contained individual ORF5 from different isolates (Balasuriya et al., 2004). Also, the role of individual envelope proteins of GP2 through M for cross-neutralization was studied using the VR-2332 infectious clone as a backbone (Kim and Yoon, 2008). The PRRSV-01 strain is highly susceptible to serum neutralization and induces atypically rapid and robust neutralizing antibodies in pigs. Analysis of structural genes of PRRSV-01 reveals the absence of two N-linked glycosylation sites each in GP3 and GP5. The significance of missing glycans for neutralization has been determined by replacing GP3 and GP5 genes from PRRSV-01 (Vu et al., 2011). The major virulence determinants have also been identified by gene swapping experiments to locate in nsp3 through nsp8 and GP5 (Kwon et al., 2008). Highly pathogenic PRRSV contains the 30 aa deletion in nsp2 sequence (Tian et al., 2007). By gene swapping studies using nsp2 from an avirulent PRRSV, the deletion in nsp2 was shown to be irrelevant to virulence and pathogenicity (Zhou et al., 2009). A recent study identified nsp9- and nsp10-coding regions together were essential for increased pathogenicity and fatal virulence for HP-PRRSV by swapping these regions between the highly and low pathogenic strains (Li et al., 2014). The inter-genotypic 5′-UTR swap between genotypes I and II was investigated and shows that the 5′-UTR of genotype II may be substituted with the corresponding sequence from genotype I, while the substitution of 5′- UTR of genotype I with its corresponding sequence from genotype II is lethal (Gao et al., 2013). Using this approach, the envelope proteins representing GP2 through GP5 of genotype I are shown to be fully functional for genotype II when using genotype II as a backbone (Tian et al., 2011).

5.3. Rational design for a new PRRS vaccine

A random sequence shuffling has been employed to generate immunologic variants of PRRSV (Ni et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2012, Zhou et al., 2013). GP3 sequences representing immunologically diverse strains of PRRSV are randomly shuffled, and the shuffled gene is incorporated in the infectious clone to generate a new virus that contains a new GP3 gene, which may improve the cross neutralization (Zhou et al., 2012). The breeding of GP4 and M have also been tried, and the rescued virus induces a broad spectrum of cross-neutralizing antibodies (Zhou et al., 2013). The GP5 sequence from 7 genetically diverse strains of PRRSV and the GP5-M sequence from 6 different strains were subjected to breeding, and the shuffled genes were cloned in infectious clones for the generation of new viruses. Two representative chimeric viruses, DS722 by GP5 shuffling and DS5M3 by GP5-M shuffling, were found to be clinically attenuated (Ni et al., 2013). This approach allows rapid generation of an attenuated virus and may be useful for vaccine development for antigenetically variable viruses (Ni et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2012). Another approach to the rapid generation of attenuated PRRSV is referred to as SAVE (synthetic attenuated virus engineering). Codon-pair bias is a phenomenon that certain codon pairs appear in a higher frequency in comparison to other synonymous codon pairs for the same amino acid, and the codon-pair bias is host species-dependent related to the efficiency of protein synthesis (Coleman et al., 2008, Moura et al., 2007, Mueller et al., 2010). By deoptimizing the codon pair of a virulence gene, an expression level of this protein decreases. The computer-aided deoptimization of codon-pairs modifies only naturally optimized pairs of codons and does not change the amino acid sequence (Mueller et al., 2010). Using this approach, the GP5 gene was codon-pair deoptimized, and a new virus was generated. The modified GP5 sequence did not affect the viability of PRRSV and the engineered virus was clinically attenuated in pigs (Ni et al., 2014).

To fulfill serological discrimination between naturally infected and vaccinated animals, removing an immunodominant epitope has been applied to developing a live-attenuated differentiating infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) vaccine against PRRSV (de Lima et al., 2008, Vu et al., 2013). The serologic marker antigen selected for DIVA vaccine should be highly immunodominant without disrupting protective well-conserved epitopes among PRRSV isolates and stability during passages. Besides, the removal of a selected epitope should not adversely affect the growth property or virulence of the mutant virus (de Lima et al., 2008, Vu et al., 2013). Two epitopes residing in nsp2 and M have been identified fulfilling the requirements for PRRSV DIVA vaccine (de Lima et al., 2008, Vu et al., 2013). Two mutants, FLdNsp2/44 with a deletion of residues 431–445 within nsp2, and Q164R disrupting antigenicity of epitope M201 in M protein have been designed and constructed accordingly (de Lima et al., 2008, Vu et al., 2013). The immunogenicity of those two epitopes has been eliminated during infection of PRRSV mutants, and both epitopes may be used as an immunologic marker for DIVA vaccine development (de Lima et al., 2008, Vu et al., 2013).

5.4. PRRSV as a foreign gene expression vector

PRRSV may serve as a vaccine vector. PRRSV infectious clones have been developed as a gene delivery vector for foreign gene expression. Identification of gene insertion sites in the viral genome and viral infectivity is critical for gene delivery. GFP and B-cell epitopes of the Newcastle disease virus (NDV) nucleoprotein have been inserted into non-essential regions of nsp2 of PRRSV (Fang et al., 2006b, Fang et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2007, Xu et al., 2012a). In this approach however, the stability of the inserted gene was of a concern. When PRRSV expressing GFP in nsp2, PRRSV SD01-08-GFP, was cell-culture passaged, a population of GFP-expression negative-virus appears by the 7th passage. Sequencing shows a deletion of GFP at the N-terminal half (1 to 159), leading to the loss of GFP expression. Insertion of 2 amino acids at position 160 of GFP was also observed in some viral clones (Fang et al., 2006b). The stability of the GFP gene in this recombinant virus was improved by deleting the ES4 epitope located downstream of the GFP gene, and the GFP expression in this virus was stable for 10 passages. However, R97C mutation was found in GFP, and this mutation caused the loss of florescence (Fang et al., 2008). The loss of fluorescence was also observed in two other GFP recombinant viruses during serial passages. In another study, the GFP-coding sequence remained intact but point mutations were identified and these mutations caused amino acid changes to R96C and N106Y (Kim et al., 2007). The expression of 49 aa B-cell epitope of the NDV nucleoprotein in PRRSV nsp2 remained stable in cell culture up to 20 passages (Xu et al., 2012a, Zhang et al., 2011). The instability of foreign gene insertion in nsp2 is not fully understood. The length of insertion may be important for stability.

An attempt was made to produce an additional mRNA for foreign gene expression. The GFP gene was inserted between ORF1b and ORF2a for PRRSV along with a copy of TRS (Lee et al., 2005, Pei et al., 2009, Sang et al., 2012, Yoo et al., 2004). Compared to insertion in nsp2, this site is suitable for foreign gene insertion since the recombinant virus was stable for up to at least 37 passages without the loss of gene or fluorescence (Pei et al., 2009). The genetic stability of genes inserted at this site has been confirmed by expressing other genes including DsRed, Renilla luciferease, IFNα1, IFNβ, IFNδ3, and IFNω5 (Sang et al., 2012). This approach has the particular advantage of eliminating the need to alter the coding sequence of a viral gene and also of minimizing the effects on expression and post-translational modification of viral proteins (Pei et al., 2009).

5.5. Application of infectious clones to structure function studies

Infectious clones are important molecular tools to study structure function relationships of proteins and genomic sequences at the infectious virus level in vivo. Specific sequence motifs may be mutated or deleted from the virus and their phenotypes may be examined to determine their functions. The removal of N-linked glycosylation at N34 and N51 of GP5 results in a mutant virus with its phenotype of enhanced sensitivity to serum neutralization and high level induction of neutralizing antibodies (Ansari et al., 2006). Elimination of N44-linked glycan is not in concert with a high-level neutralizing antibody response to wild type PRRSV (Wei et al., 2012). Meanwhile, introduction of multiple mutations at these N-linked glycosylation sites could significantly reduce virus yields (Wei et al., 2012). The E gene knock-out mutation allows for genome replication and transcription but does not produce infectious progeny, indicating that the E protein is essential for virion assembly (Lee and Yoo, 2006). PRRSV nsp1 is a multifunctional protein regulating the accumulation of genomic RNA and mRNAs. It also has the ability to modulate the host innate immunity by suppressing the type I IFN production (Nedialkova et al., 2010, Sun et al., 2012a; Yoo et al., 2010). The motifs for zinc fingers, PLPs, and nuclease have been identified in nsp1 (Fang and Snijder, 2010, Snijder et al., 2013, Xue et al., 2010). By deleting from the genome, nsp1 is shown to be dispensable for genome replication but crucial for mRNA transcription. Mutation in the catalytic sites of PLP1 impairs both viral genome and mRNA synthesis as well as the cleavage between nsp1 and nsp2. Mutations in the zinc finger motif abolished the mRNA transcription, whereas genome replication was not affected (Tijms et al., 2001, Tijms et al., 2007). When the catalytic sites of PLP1α are mutated using a PRRSV infectious clone, the proteinase activity disappears and mRNA synthesis is completely blocked. In contrast, mutations at the PLP1β catalytic sites result in no mRNA synthesis and no viral infectivity, indicating that the normal cleavage of nsp1 and nsp2 is critical for viral replication (Kroese et al., 2008).

To design effective vaccine candidates that may be useful to overcoming antigenic heterogeneity of PRRS, extensive studies have been conducted to eliminate the IFN antagonistic function from the virus (see reviews Snijder et al., 2013, Sun et al., 2012a; Yoo et al., 2010). Among viral proteins, nsp1α and nsp1β have been identified as potent IFN analogists (Beura et al., 2010, Chen et al., 2010a, Han et al., 2013, 2014; Kim et al., 2010, Song et al., 2010). Subsequent studies have identified specific residues regulating the IFN antagonism, and a mutant virus with a stretch of alanine substitution at positions 16–20 of nsp1β showed the loss of IFN suppression (Beura et al., 2012). In another study, K124 and R128 were mutated to release the surface accessibility of nsp1β, and mutant PRRSV impaired the IFN antagonism (Li et al., 2013).

Motifs in the N protein have broadly been studied using mutant viruses. The importance of N protein dimerization has been examined by mutating C23S which is responsible for the covalent interaction between N proteins. Mutant viruses of C23S, C75S, and C90S were constructed, and with the exception of C75S, both C23S and C90S completely lost their infectivity. In another study however, the replacement of cysteines within N protein, either singly or in combination, did not impair the growth PRRSV according (Zhang et al., 2012). Genome replication and mRNA transcription were normal for both mutants, suggesting the dimerization of N may be important for particle assembly or maturation (Lee et al., 2005). The nuclear localization signal (NLS) of N was also mutated to examine the biological consequence of N in the nucleus in PRRSV-infected cells. Compared to wild-type PRRSV, NLS-null mutant PRRSV was attenuated in pigs and produced a significantly shorter mean duration of viremia and higher titers of neutralizing antibodies (Lee et al., 2006, Pei et al., 2008), demonstrating that the N protein nuclear localization is a virulence factor.

6. Conclusions

As an emerged and re-emerging disease in swine, PRRS has extensively been studied for molecular biology, immunology, and prevention. The unusual immune responses in pigs and antigenic heterogeneity of the virus are two main obstacles to developing a satisfactory PRRS vaccine. The availability of PRRSV infectious clones and recent advances in recombinant DNA technology have made possible to manipulate the viral genome to introduce specific mutations to targeted sequences and to create genetically modified mutant viruses. Extensive efforts have been applied to making mutant viruses with modified phenotypes of immune responses including the evasion of neutralizing antibodies and suppressed innate immune responses. For viral heterogeneity, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is believed to cause frequent mutations in the PRRSV genome. Genetic swapping or modifications of nsp9, the RdRp of PRRSV, may be studied to make mutant viruses with reduced mutation rates during replication. The reverse genetics of PRRSV is a powerful genetic tool and has the potential to apply to the basic understanding of the biology of PRRSV and to the development of genetically modified vaccines and gene delivery.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the US National Pork Board (grant #13-245) and Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI) Competitive Grant no. 2013-67015-21243 of the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA).

References

- Allende R., Lewis T.L., Lu Z., Rock D.L., Kutish G.F., Ali A., Doster A.R., Osorio F.A. North American and European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses differ in non-structural protein coding regions. J. Gen. Virol. 1999;80:307–315. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-2-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almazan F., Gonzalez J.M., Penzes Z., Izeta A., Calvo E., Plana-Duran J., Enjuanes L. Engineering the largest RNA virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5516–5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari I.H., Kwon B., Osorio F.A., Pattnaik A.K. Influence of N-linked glycosylation of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus GP5 on virus infectivity, antigenicity, and ability to induce neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 2006;80:3994–4004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.3994-4004.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasuriya U.B.R., Dobbe J.C., Heidner H.W., Smalley V.L., Navarrette A., Snijder E.J., MacLachlan N.J. Characterization of the neutralization determinants of equine arteritis virus using recombinant chimeric viruses and site-specific mutagenesis of an infectious cDNA clone (vol 321, pg 235, 2004) Virology. 2004;327:318–319. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benfield D.A., Nelson E., Collins J.E., Harris L., Goyal S.M., Robison D., Christianson W.T., Morrison R.B., Gorcyca D., Chladek D. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (Isolate ATCC VR-2332) J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 1992;4:127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura L.K., Sarkar S.N., Kwon B., Subramaniam S., Jones C., Pattnaik A.K., Osorio F.A. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1beta modulates host innate immune response by antagonizing IRF3 activation. J. Virol. 2010;84:1574–1584. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01326-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beura L.K., Subramaniam S., Vu H.L.X., Kwon B., Pattnaik A.K., Osorio F.A. Identification of amino acid residues important for anti-IFN activity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1. Virology. 2012;433:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer J.C., Haenni A.L. Infectious transcripts and cDNA clones of RNA viruses. Virology. 1994;198:415–426. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramel-Verheije M.H.G., Rottier P.J.M., Meulenberg J.J.M. Expression of a foreign epitope by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2000;278:380–389. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand R.J., Trible B.R., Rowland R.R.R. Pathogenesis of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Lawson S., Sun Z., Zhou X., Guan X., Christopher-Hennings J., Nelson E.A., Fang Y. Identification of two auto-cleavage products of nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infected cells: nsp1 function as interferon antagonist. Virology. 2010;398:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.H., Zhou X.X., Lunney J.K., Lawson S., Sun Z., Brown E., Christopher-Hennings J., Knudsen D., Nelson E., Fang Y. Immunodominant epitopes in nsp2 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus are dispensable for replication, but play an important role in modulation of the host immune response. J. Gen. Virol. 2010;91:1047–1057. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.R., Papamichail D., Skiena S., Futcher B., Wimmer E., Mueller S. Virus attenuation by genome-scale changes in codon pair bias. Science. 2008;320:1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1155761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima M., Kwon B., Ansari I.H., Pattnaik A.K., Flores E.F., Osorio F.A. Development of a porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus differentiable (DIVA) strain through deletion of specific immunodominant epitopes. Vaccine. 2008;26:3594–3600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima M., Pattnaik A.K., Flores E.F., Osorio F.A. Serologic marker candidates identified among B-cell linear epitopes of Nsp2 and structural proteins of a North American strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2006;353:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries A.A., Glaser A.L., Raamsman M.J., de Haan C.A., Sarnataro S., Godeke G.J., Rottier P.J. Genetic manipulation of equine arteritis virus using full-length cDNA clones: separation of overlapping genes and expression of a foreign epitope. Virology. 2000;270:84–97. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dea S., Gagnon C.A., Mardassi H., Pirzadeh B., Rogan D. Current knowledge on the structural proteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus: comparison of the North American and European isolates. Arch. Virol. 2000;145:659–688. doi: 10.1007/s007050050662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon J.A., Faaberg K.S., Meulenberg J.J.M., Wassenaar A.L.M., Plagemann P.G.W., Gorbalenya A.E., Snijder E.J. Processing and evolution of the N-terminal region of the Arterivirus replicase ORF1a protein – identification of 2 papain-like cysteine proteases. J. Virol. 1995;69:4500–4505. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4500-4505.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon J.A., Snijder E.J., Chirnside E.D., Devries A.A.F., Horzinek M.C., Spaan W.J.M. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the coronaviruslike superfamily. J. Virol. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doan D.N., Dokland T. Structure of the nucleocapsid protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Structure. 2003;11:1445–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbe J.C., van der Meer Y., Spaan W.J.M., Snijder E.J. Construction of chimeric arteriviruses reveals that the ectodomain of the major glycoprotein is not the main determinant of equine arteritis virus tropism in cell culture. Virology. 2001;288:283–294. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Christopher-Hennings J., Brown E., Liu H., Chen Z., Lawson S.R., Breen R., Clement T., Gao X., Bao J., Knudsen D., Daly R., Nelson E. Development of genetic markers in the non-structural protein 2 region of a US type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: implications for future recombinant marker vaccine development. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:3086–3096. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/003426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Faaberg K.S., Rowland R.R., Christopher-Hennings J., Pattnaik A.K., Osorio F., Nelson E.A. Construction of a full-length cDNA infectious clone of a European-like type 1 PRRSV isolated in the US. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;581:605–608. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-33012-9_110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Kim D.Y., Ropp S., Steen P., Christopher-Hennings J., Nelson E.A., Rowland R.R. Heterogeneity in Nsp2 of European-like porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses isolated in the United States. Virus Res. 2004;100:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Rowland R.R., Roof M., Lunney J.K., Christopher-Hennings J., Nelson E.A. A full-length cDNA infectious clone of North American type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: expression of green fluorescent protein in the Nsp2 region. J. Virol. 2006;80:11447–11455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01032-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Snijder E.J. The PRRSV replicase: exploring the multifunctionality of an intriguing set of nonstructural proteins. Virus Res. 2010;154:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Treffers E.E., Li Y.H., Tas A., Sun Z., van der Meer Y., de Ru A.H., van Veelen P.A., Atkins J.F., Snijder E.J., Firth A.E. Efficient-2 frameshifting by mammalian ribosomes to synthesize an additional arterivirus protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:E2920–E2928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211145109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth A.E., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., Wills N.M., Go Y.Y., Balasuriya U.B.R., Atkins J.F., Snijder E.J., Posthuma C.C. Discovery of a small arterivirus gene that overlaps the GP5 coding sequence and is important for virus production. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1097–1106. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029264-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias-Staheli N., Giannakopoulos N.V., Kikkert M., Taylor S.L., Bridgen A., Paragas J., Richt J.A., Rowland R.R., Schmaljohn C.S., Lenschow D.J., Snijder E.J., Garcia-Sastre A., Virgin H.W. Ovarian tumor domain-containing viral proteases evade ubiquitin- and ISG15-dependent innate immune responses. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:404–416. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Lu J.Q., Yao H.C., Wei Z.Z., Yang Q., Yuan S.S. Cis-acting structural element in 5′ UTR is essential for infectivity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 2012;163:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Yao H., Lu J., Wei Z., Zheng H., Zhuang J., Tong G., Yuan S. Replacement of the heterologous 5′ untranslated region allows preservation of the fully functional activities of type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2013;439:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z.Q., Guo X., Yang H.C. Genomic characterization of two Chinese isolates of porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus. Arch. Virol. 2004;149:1341–1351. doi: 10.1007/s00705-004-0292-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B.Q., Lager K.M., Henningson J.N., Miller L.C., Schlink S.N., Kappes M.A., Kehrli M.E., Brockmeier S.L., Nicholson T.L., Yang H.C., Faaberg K.S. Experimental infection of United States swine with a Chinese highly pathogenic strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 2013;435:372–384. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Liu G., Wang Y., Faaberg K.S. Identification of nonessential regions of the nsp2 replicase protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus strain VR-2332 for replication in cell culture. J. Virol. 2007;81:9878–9890. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00562-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Rutherford M.S., Faaberg K.S. The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nsp2 cysteine protease domain possesses both trans- and cis-cleavage activities. J. Virol. 2009;83:9449–9463. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00834-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J., Wang Y., Faaberg K.S. Complete genome analysis of RFLP 184 isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res. 2006;122:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.Y., Du Y.J., Song C., Yoo D.W. Degradation of CREB-binding protein and modulation of type I interferon induction by the zinc finger motif of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nsp1 alpha subunit. Virus Res. 2013;172:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C.R., Griggs T.F., Gnanandarajah J., Murtaugh M.P. Novel structural protein in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus encoded by an alternative ORF5 present in all arteriviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011;92:1107–1116. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur V., Elam M.R., Pawlovich T.M., Murtaugh M.P. Genetic variation in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates in the midwestern United States. J. Gen. Virol. 1996;77:1271–1276. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.Y., Calvert J.G., Chang K.O., Horlen K., Kerrigan M., Rowland R.R.R. Expression and stability of foreign tags inserted into nsp2 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Virus Res. 2007;128:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim O., Sun Y., Lai F.W., Song C., Yoo D. Modulation of type I interferon induction by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus and degradation of CREB-binding protein by non-structural protein 1 in MARC-145 and HeLa cells. Virology. 2010;402:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W.I., Yoon K.J. Molecular assessment of the role of envelope-associated structural proteins in cross neutralization among different PRRS viruses. Virus Genes. 2008;37:380–391. doi: 10.1007/s11262-008-0278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroese M.V., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., Ruijter J.N.A.B.D., Peeters B.P.H., Meulenberg J.J.M., Cornelissen L.A.H.M., Snijder E.J. The nsp1 alpha and nsp1 beta papain-like autoproteinases are essential for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus RNA synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:494–499. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B., Ansari I.H., Osorio F.A., Pattnaik A.K. Infectious clone-derived viruses from virulent and vaccine strains of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus mimic biological properties of their parental viruses in a pregnant sow model. Vaccine. 2006;24:7071–7080. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon B., Ansari I.H., Pattnaik A.K., Osorio F.A. Identification of virulence determinants of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus through construction of chimeric clones. Virology. 2008;380:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Calvert J.G., Welich S.K.W., Yoo D. A DNA-launched reverse genetics system for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus reveals that homodimerization of the nucleocapsid protein is essential for virus infectivity. Virology. 2005;331:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Hodgins D., Calvert J.G., Welch S.K.W., Jolie R., Yoo D. Mutations within the nuclear localization signal of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein attenuate virus replication. Virology. 2006;346:238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Yoo D. Cysteine residues of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus small envelope protein are non-essential for virus infectivity. J. Gen. Virol. 2005;86:3091–3096. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Yoo D. The small envelope protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus possesses ion channel protein-like properties. Virology. 2006;355:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou L., Zhang J., Ge X., Zhou R., Zheng H., Geng G., Guo X., Yang H. Nsp9 and Nsp10 contribute to the fatal virulence of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus emerging in China. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004216. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhu L., Lawson S.R., Fang Y. Targeted mutations in a highly conserved motif of the nsp1beta protein impair the interferon antagonizing activity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:1972–1983. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.051748-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Zhang J., Huang C.M., Go Y.Y., Faaberg K.S., Rowland R.R., Timoney P.J., Balasuriya U.B. Chimeric viruses containing the N-terminal ectodomains of GP5 and M proteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus do not change the cellular tropism of equine arteritis virus. Virology. 2012;432:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv J., Zhan J.W., Sun Z., Liu W.Q., Yuan S.S. An infectious cDNA clone of a highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus variant associated with porcine high fever syndrome. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:2075–2079. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/001529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg J.J.M., BosDeRuijter J.N.A., vandeGraaf R., Wensvoort G., Moormann R.J.M. Infectious transcripts from cloned genome-length cDNA of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Virol. 1998;72:380–387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.380-387.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg J.J.M., Hulst M.M., Demeijer E.J., Moonen P.L.J.M., Denbesten A., Dekluyver E.P., Wensvoort G., Moormann R.J.M. Lelystad virus, the causative agent of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (PEARS), is related to LDV and EAV. Virology. 1993;192:62–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers G., Tautz N., Becher P., Thiel H.J., Kummerer B.M. Recovery of cytopathogenic and noncytopathogenic bovine viral diarrhea viruses from cDNA constructs. J. Virol. 1997;71:1735. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1735-1735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moormann R.J., van Gennip H.G., Miedema G.K., Hulst M.M., van Rijn P.A. Infectious RNA transcribed from an engineered full-length cDNA template of the genome of a pestivirus. J. Virol. 1996;70:763–770. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.763-770.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura G., Pinheiro M., Arrais J., Gomes A.C., Carreto L., Freitas A., Oliveira J.L., Santos M.A. Large scale comparative codon-pair context analysis unveils general rules that fine-tune evolution of mRNA primary structure. PLoS One. 2007;2:e847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller S., Coleman J.R., Papamichail D., Ward C.B., Nimnual A., Futcher B., Skiena S., Wimmer E. Live attenuated influenza virus vaccines by computer-aided rational design. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:723–726. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y., Kato A., Tsuda T., Morozumi T., Miura Y., Sugimura T. Isolation and serological characterization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) viruses from pigs with reproductive and respiratory disorders in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1994;56:891–894. doi: 10.1292/jvms.56.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh M.P., Elam M.R., Kakach L.T. Comparison of the structural protein-coding sequences of the VR-2332 and Lelystad virus-strains of the PRRS virus. Arch. Virol. 1995;140:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/BF01322671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Music N., Gagnon C.A. The role of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus structural and non-structural proteins in virus pathogenesis. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2010;11:135–163. doi: 10.1017/S1466252310000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedialkova D.D., Gorbalenya A.E., Snijder E.J. Arterivirus np1 modulates the accumulation of minus-strand templates to control the relative abundance of viral mRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000772. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen C.J., Murtaugh M.P., Faaberg K.S. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution on two continents. J. Virol. 1999;73:270–280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.270-280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Y.Y., Huang Y.W., Cao D.J., Opriessnig T., Meng X.J. Establishment of a DNA-launched infectious clone for a highly pneumovirulent strain of type 2 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: identification and in vitro and in vivo characterization of a large spontaneous deletion in the nsp2 region. Virus Res. 2011;160:264–273. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]