Abstract

Social distancing at its various levels has been a key measure to mitigate the transmission of COVID-19. The implementation of strict measures for social distancing is challenging, including in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) due to its level of urbanization, its social and religious norms and its annual hosting of high visibility international religious mass gatherings. KSA started introducing decisive social distancing measures early before the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the Kingdom. These ranged from suspension or cancelations of religious, entertainment and sporting mass gatherings and events such as the Umrah, temporary closure of educational establishments and mosques and postponing all non-essential gatherings, to imposing a curfew. These measures were taken in spite of their socio-economic, political and religious challenges in the interest of public and global health. The effect of these actions on the epidemic curve of the Kingdom and on the global fight against COVID-19 remains to be seen. However, given the current COVID-19 situation, further bold and probably unpopular measures are likely to be introduced in the future.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Public health, Social distancing, Pandemic, Saudi Arabia

Coronavirus disease COVID-19 caused by the novel human coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first detected in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and has since spread across the world [1]. On the 30th of January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COIVD-19 a public health emergency of international concern and 6-weeks later the outbreak was characterized as a pandemic. As of the March 25, 2020, the WHO reports 414,179 cases of COVID-19 globally causing 18,440 deaths [1]. The WHO's global risk assessment for the situation remains “very high”. The rapid spread of the disease, the increasing number of cases and associated mortality as well as the lack of therapeutic and vaccine options, prompted many governments and health authorities to implement strict measures to combat the pandemic. These include community lockdown, travel and movement restrictions, and cancelation of events and non-essential gatherings [2]. Data suggests that countries which implemented decisive and early interventions may have helped in reducing the spread of the disease and flattening their epidemic curves [3,4]. Countries with previous experience of coronavirus outbreaks, notably Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), such as Singapore, are a good example [4].

A key measure to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 has been social distancing, aimed at reducing the probability of contact between infected persons and others who are not infected [5]. The implementation of social distancing measures can be problematic, especially when such measures have a significant impact on social norms, the economy and the psychological wellbeing of the population. Several factors make the implementation of strict social distancing measures particularly challenging in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) including its level or urbanization, its social and religious norms, its hosting of annual religious mass gatherings as well as its ongoing social and economic transformation in line with its 2030 vision [6].

Over 80% of the Saudi population lives in urban areas, usually in an average of six persons households [7]. Traditionally, social life in the Kingdom has revolved around the home and family and social gatherings, family visits and events are common. In recent years, in line with the Saudi vision 2030, the Kingdom has invested in positioning the country as a hub for business and tourism, aiming to attract millions of visitors each year [6]. The establishment of the Saudi Ministry of Culture and the inception of the sports and entertainment authorities in the Kingdom resulted in an ever-increasing number of national and international social, cultural, entertainment and sporting events across Saudi Arabia in recent years. This led to a more vibrant social life outside the confines of the home with additional investments in public venues such as cinemas, restaurants, coffee shops, shopping malls, gyms, museums, cultural and social centres and swimming pools.

Religion is another major pillar of Saudi society. The country is the location of the holiest places in the Islamic faith, the cities of Makkah and Medina, where the Two Holy Mosques are located. KSA annually hosts the Hajj and Umrah religious mass gatherings. These are high visibility international events attracting over 10 million pilgrims from over 180 different countries. The Umrah is a nearly all-year-round event while the Hajj takes place during the 12th month of the Islamic calender [8]. These gatherings are by their nature crowded settings that can facilitate the transmission of infectious diseases, including human to human transmission of respiratory pathogens [9]. They can rapidly amplify transmission and may lead to the international spread of infections through the globalization or respiratory agents via returning participants [9,10]. Furthermore, group prayer is also important in the Islamic religion. Mosques typically hold five group prayers each day in addition to the Friday midday prayer, which is often longer and attended by a larger number of worshipers.

Saudi Arabia has robust preparedness and public health response capabilities strengthened by the valuable experience gained during its managing of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) reported in 2012 and decades of planning religious mass gatherings in the face or numerous public health challenges. A testament to this is the Kingdom's recent successful planning and management of the Hajj in the midst of infectious diseases outbreaks and public health emergencies of international concern, including the H1N1 pandemic influenza and the SARS, MERS, rift valley fever, ZIKA and Ebola virus disease outbreaks [11]. KSA is currently drawing on these successful experiences to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

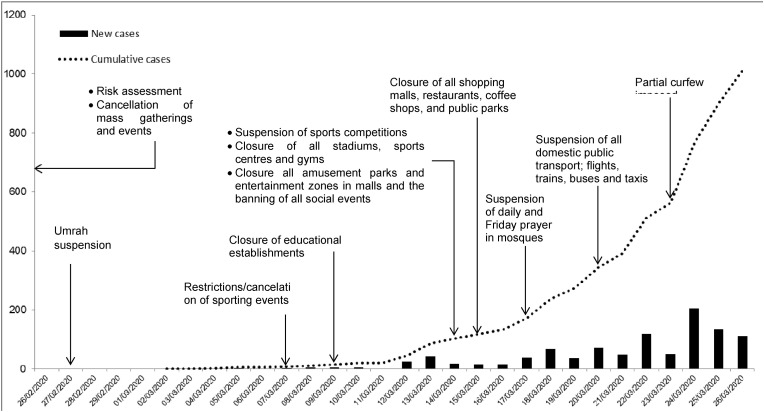

KSA authorities were monitoring the COVID-19 situation from the time it was first detected and plans were put in motion to prepare for the potential spread of the disease to the Kingdom. These included measures for social distancing. Given their potential role in spreading COVID-19, [12] risk assessment for mass gatherings and events using a modified Jeddah Tool [13] were conducted before the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in the Kingdom. As a result, a number of sporting, cultural and entertainment events were canceled. Of note, on the 27th of February 2020, the Kingdom suspended the Umrah mass gathering for the first time in many decades (Fig. 1 ). This bold measure was taken in the interest of public health despite its potential economic and political consequence as well as its personal financial, mental and emotional impact on pilgrims [14]. Nevertheless, due to its potential as a super-spreading event, this suspension may have avoided significant global dissemination of the virus via returning pilgrims.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative and daily cases of COVID-19 and key social distancing interventions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as of the 26th of March 2020.

On the 2nd of March 2020, the first case of COVID-19 was reported by the Saudi authorities. The case was an exported case in a Saudi national returning from Iran via Bahrain. Soon after, the Saudi Ministry of Sports announced that all sports competitions would be held behind closed doors as of the 7th of March 2020 in addition to the suspension of the 2020 Saudi Olympics Games, which was planned to start on the 23rd of March 2020. On the 8th of March 2020, the Saudi Ministry of Education declared the closure of schools and suspension of teaching at universities and other institutions until further notice to avoid the spread of the disease through these congregated settings. The decision covered all educational institutions, including public and private schools, and technical and vocational training establishments. Home-schooling and online teaching were promoted. Reactive school closure has been shown to weaken the network of social interactions, to reduce and delay the epidemic peak and to minimize the spread of seasonal and pandemic Influenza [15,16].

Up to the 9th of March 2020, only imported cases were reported in KSA. On the 10th or March 2020, with a total of 20 COVID-19 cases and five new confirmed cases, local transmission was documented in the country. The following few days saw a progression towards the closure of other activities and locations that could increase close contact between people. These included further suspension of events and celebrations, conference and sporting activities, and closure of cinemas, markets, shopping malls, restaurants and coffee shops, as well as office buildings with alternatives being introduced including working from home, teleconferencing and online shopping. On the 14th of March 2020, the Saudi Ministry of Sports announced that all sports competitions and activities would be suspended as well as the closure of all stadiums, sports centres and gyms. On the same day, the Saudi authorities announced the closure of all amusement parks and entertainment zones in malls and the banning of all social events, including funerals and weddings. The next day, closure of all indoor shopping malls, restaurants, coffee shops, and public parks was also announced. Restaurants and coffee shops (if not located in an indoor mall) were allowed to provide takeaways and delivery services only. To reduce the impact on the public and evert panic-buying, supermarkets, shops and other premises for essential products and services remained opened with working times extended in some cases to ensure that people obtained their essentials while reducing crowding at these settings. Delivery services were encouraged with many online applications available.

As the number of COVID-19 cases increased globally, accumulating evidence of transmission linked to places of worship was reported from countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Iran and Malaysia. Recognizing the potential risk of these often crowded places of worship in the spread of the virus, KSA, represented by the Saudi Council of Senior Scholars, took the unprecedented step of temporarly closing its 80,000 mosques and suspending the daily and Friday prayer in these locations. Since the 17th of March 2020, call for prayer heard across the Kingdom instructs people to pray in their homes as to avoid close contact. The Kingdom's Two Holy Mosques in Makkah and Medina were also temporally closed for the public. The above measures were decisive and bold given the importance of religion in the Kingdom and the significance of KSA in the Muslim world. The temporary suspension of group prays and the temporary closure of the Two Holy Mosques, may be unpopular among some, yet, they are a welcomed action that could encourage other Muslim countries to take similar measures to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission.

In the face of increasing number of COVID-19 cases in the Kingdom (Fig. 1), by the 20th or March 2020, the Saudi authorities suspended all domestic public transport; flights, trains, buses and taxis in a heightened effort to stop the spread of the virus. Public transport brings people into close contact in a confined space and therefore is a risk for COVID-19 transmission. Taxis, in particular, are commonly used in the daily lives of many people in KSA. Taxi drivers are at an increased risk of acquiring the virus, given their close contact with their customers. The quick customer turnaround also means that a single case among taxi drivers could then transmit the virus to potentially a large number of people in the community. Taxi sharing applications continued to be available as to balance between the need for taxi services among some segments of the population and the duty to protect the public, in addition to the ability to trace with application users.

Despite all of the above measures, social interactions continued among the population, especially during the evenings. As a consequence, the Saudi Authorities declared a partial curfew in the Kingdom as of the 23nd of March 2030. Initially, the public was requested to stay home from 7 pm till 6 am except for those with authorizations or for exceptional circumstances. Later, the curfew duration was prolonged in some cities such as the capital Riyadh and Makkah and Medina to 3 pm till 6 am. The curfew was backed by significant penalties for breaking it. Financial and legal ramifications for not adhering to public health measures were introduced in other countries during the SARS outbreak and were found to be useful for compliance [17]. As of the time of writing this article, the curfew is partial but may be extended to a full lockdown depending on how the COVID-19 situation progresses in the Kingdom.

As of the 26th of March 2020, 1012 cases of COVID-19 have been identified in KSA with three fatalities. While these numbers are currently lower than many other countries, they are still on the increase. The strict and decisive social distancing measures introduced by the Kingdom in the face of political, social, economic and religious challenges may have played an important part in shaping the epidemic curve of the disease in the country. The effectiveness of these measures remains to be seen as the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic continues. However, undoubtedly the success of these interventions and compliance with them are highly linked to effective risk communication with the public to convey the reasoning behind, and aims of, such actions. Risk communication has been and will remain and integral part of the Kingdom's effect to stop the spread of COVID-19. The Kingdom still faces important decisions in the current pandemic, notably a decision on the upcoming 2020 Hajj [18]. The pilgrimage is compulsory for all Muslims who are physically and financially able to perform it. Many Muslims around the world save and wait decades for the opportunity to perform Hajj, and a decision to suspend the Hajj would have a significant impact within and outside the Kingdom [11]. The decision on the 2020 Hajj will be an informed weighing between the risk of the pilgrimage going ahead and the consequence of it being suspended. The priority will be protecting the public and ensuring global health security.

The Saudi authorities are carefully monitoring the COVID-19 situation and the Kingdom will continue to take decisive and bold measures to safeguard its citizens, residents and visitors as well as the global community, even at a great socioeconomic cost. On a political front, the Kingdom leveraged its current presidency of the G20 to host an emergency summit on the COVID-19 pandemic, on the 26th of March 2020, to advance the coordinated response. During this virtual summit, G20 leaders pledged their commitment to presenting a united front against the current pandemic, calling it their “absolute priority” to tackle its health, social and economic impacts. While experiences from China, South Korea and Singapore suggest that suppression of the spread is possible in short terms, social distancing and other draconian measures taken by various governments may not be sustainable long term if the COVID-19 pandemic continues. Also, transmission may quickly rebound if interventions are relaxed [19]. Hence, other strategies may need to be introduced as well as tactical decisions regarding the currently implemented measures [3,17]. For instance, intermittent social distancing, informed by trends in disease surveillance data may be an option, where interventions could be relaxed temporarily for short periods and reinforced if the number of cases starts to rise [19]. Ultimately, if COVID-19 transmission continues, a drastic move from reactive to active measures to deal with the virus head-on will be required. Aggressive case finding and isolation, rigorous contact tracing, quarantining, and testing, as well as community-wide surveillance, will need to be implemented and sustained in addition to social distancing, travel and movement restrictions and other measures to help fight the pandemic [3].

Funding

None to declare.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Saber Yezli: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Anas Khan: Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 65. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahim S.H., Ahmed Q.A., Gozzer E., Schlagenhauf P., Memish Z.A. Covid-19 and community mitigation strategies in a pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1066. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher D., Wilder-Smith A. The global community needs to swiftly ramp up the response to contain COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10230):1109–1110. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30679-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee V.J., Chiew C.J., Khong W.X. Interrupting transmission of COVID-19: lessons from containment efforts in Singapore. J Trav Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Trav Med. 2020;27(2) doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingdom of Saudi Arabia vision 2030. 2016. http://vision2030.gov.sa/download/file/fid/417 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdul Salam A., Elsegaey I., Khraif R., Al-Mutairi A. Population distribution and household conditions in Saudi Arabia: reflections from the 2010 Census. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:530. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yezli S., Yassin Y., Awam A., Attar A., Al-Jahdali E., Alotaibi B. Umrah. An opportunity for mass gatherings health research. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(8):868–871. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.8.20124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kok J., Blyth C.C., Dwyer D.E. Mass gatherings and the implications for the spread of infectious diseases. Future Microbiol. 2012;7(5):551–553. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yezli S., Assiri A.M., Alhakeem R.F., Turkistani A.M., Alotaibi B. Meningococcal disease during the Hajj and Umrah mass gatherings. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed Q.A., Memish Z.A. The cancellation of mass gatherings (MGs)? Decision making in the time of COVID-19. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101631. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebrahim S.H., Memish Z.A. COVID-19 - the role of mass gatherings. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101617. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yezli S., Khan A.A. The Jeddah tool. A health risk assessment framework for mass gatherings. Saudi Med J. 2020;41(2):121–122. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.2.24875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebrahim S.H., Memish Z.A. Saudi Arabia’s measures to curb the COVID-19 outbreak: temporary suspension of the Umrah pilgrimage. J Trav Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Litvinova M., Liu Q.H., Kulikov E.S., Ajelli M. Reactive school closure weakens the network of social interactions and reduces the spread of influenza. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(27):13174–13181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821298116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bin Nafisah S., Alamery A.H., Al Nafesa A., Aleid B., Brazanji N.A. School closure during novel influenza: a systematic review. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(5):657–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilder-Smith A., Chiew C.J., Lee V.J. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30129-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautret P., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Hoang V.T. Covid 19: will the 2020 Hajj pilgrimage and tokyo olympic games be cancelled? Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101622. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson N M., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G. 2020. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]