The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been straining health-care systems worldwide. For countries still in the early phase of an outbreak, there is concern regarding insufficient supply of intensive care unit (ICU) beds and ventilators to handle the impending surge in critically ill patients. To inform pandemic preparations, we projected the number of ventilators that will be required in the USA at the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak.

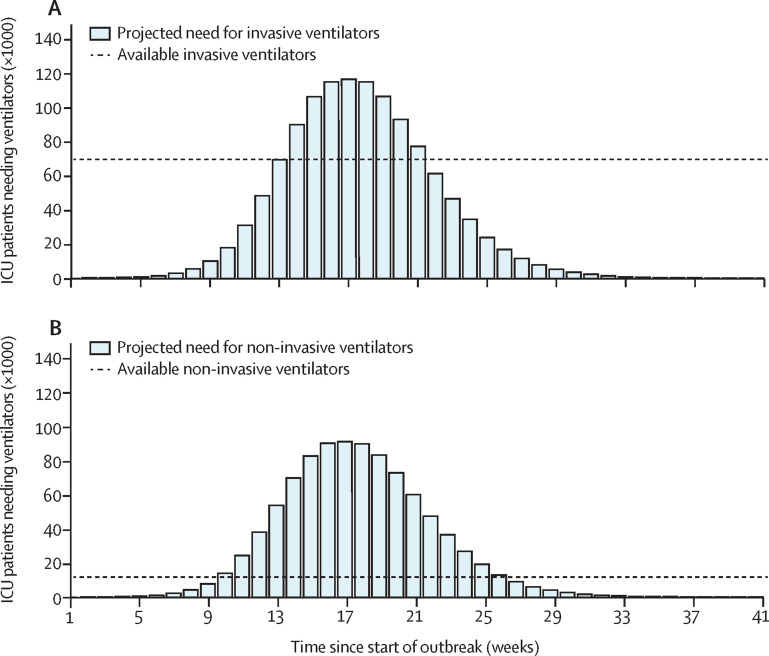

Our estimates combine recent evaluations of COVID-19 hospitalisations1 and data on the proportion of patients with COVID-19 in the ICU requiring ventilation (appendix p 2). At a basic reproduction number of 2·5,1 115 001 (IQR 101 006–131 770) invasive ventilators and 89 788 (78 861–102 880) non-invasive ventilators would be needed, on average, at outbreak peak (figure ).

Figure.

Projected number of ICU patients requiring ventilators in the absence of any community interventions with R0=2·5

Temporal need for (A) invasive ventilators and (B) non-invasive ventilators among ICU patients during the outbreak. The solid line indicates the routine availability of ventilators before the start of the outbreak. ICU=intensive care unit. R0=basic reproduction number.

Considering that 29·0% of the existing 97 776 ICU beds in the USA are routinely occupied by patients without COVID-19 requiring invasive mechanical ventilation,2, 3 we calculated that 69 660 of the 98 015 invasive ventilators in the USA before outbreak start would be available for the COVID-19 response.4, 5 These available ventilators include additional units in stockpile or storage. Consequently, at least 45 341 (IQR 31 346–62 110) additional units would be needed for the surge at the peak. Of the 22 976 non-invasive ventilators,5 we estimated that 12 499 units would be available, assuming 54·4% availability as estimated for routinely used invasive ventilators (appendix p 1). For these non-invasive devices, a minimum of 77 289 (66 362–90 381) additional units would be needed at the peak. As a step towards filling this gap, 52 635 limited-featured devices exist.5 Although these could be deployed for treatment of moderate cases, they might not be an appropriate substitute for ventilators in the care of severely ill patients.5

These estimates should represent a lower bound for additional ventilator requirements. To avoid triage for use of ventilators,6 units would have to be perfectly distributed both geographically and temporally, which in turn relies on centralised coordination among states and more precise forecasting than is currently possible given the constraints on testing for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Worryingly, areas such as New York city are experiencing the first surge of cases in the absence of national coordination, while facing competition with other regions simultaneously trying to secure these critically important resources.7 Also concerning is that the USA is already several weeks into its epidemic. With invasive ventilator needs exceeding availability at week 14 of our simulations, there are substantially fewer weeks to procure the requisite supply.

We urge three complementary avenues of action to reduce the imbalance between supply and demand for ventilators. First, vigilant social distancing has potential to flatten the curve,1 which will both delay and suppress the outbreak peak. In addition to reducing the peak demand for ventilators, the delay would provide a window of opportunity to ramp up ventilator production. Second, it is plausible that the USA will experience several asynchronous local peaks rather than one apex. A nationalised allocation system that transfers ventilators based on state-level epidemiological projections would most efficiently capitalise on existing units. Third, the USA simply needs more ventilators. In that respect, the Defense Production Act has been invoked, compelling some automobile manufacturers to shift production to ventilators.8 This Act also permits the Administration to coordinate distribution among states, thereby addressing our second recommendation. The Administration has refused to engage in coordination, suggesting that it is not yet needed. However, given the time required to refit manufacturers and begin producing ventilators, waiting until the national shortage is upon us would be disastrous. By contrast, these three steps will save lives and avoid the devastating rationing that would unfold in the absence of action.

Acknowledgments

APG acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants UO1-GM087719 and 1R01AI151176-01), the Burnett and Stender families' endowment, the Notsew Orm Sands Foundation, and a National Science Foundation grant for rapid response research (grant 2027755). MCF was supported by the NIH (grant K01 AI141576). SMM acknowledges support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant OV4-170643; Canadian 2019 Novel Coronavirus Rapid Research) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Moghadas SM, Shoukat A, Fitzpatrick MC. Projecting hospital utilization during the COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004064117. published online April 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wunsch H, Wagner J, Herlim M, Chong DH, Kramer AA, Halpern SD. ICU occupancy and mechanical ventilator use in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2712–2719. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318298a139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Hospital Association Fast facts on US hospitals. 2020. https://www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

- 4.Society of Critical Care Medicine United States resource availability for COVID-19. https://sccm.org/Blog/March-2020/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19

- 5.Rubinson L, Vaughn F, Nelson S. Mechanical ventilators in US acute care hospitals. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2010;4:199–206. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2010.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage—allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmp2005689. published online March 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whalen J, Romm T, Gregg A, Hamburger T. Scramble for medical equipment descends into chaos as US states and hospitals compete for rare supplies. March 24, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/03/24/scramble-medical-equipment-descends-into-chaos-us-states-hospitals-compete-rare-supplies

- 8.Vazquez M, Collins K, Sidner S, Hoffman J. Trump invokes Defense Production Act to require GM to make ventilators. March 27, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/27/politics/general-motors-ventilators-defense-production-act/index.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.