Abstract

Parallels of cancer with ecology and evolution have provided new insights into the initiation and spread of cancer, and new approaches to therapy. This review describes those parallels while emphasizing some key contrasts. We argue that cancers are less like invasive species than like native species or even crops that have escaped control, and that ecological control and homeo-static control differ fundamentally through both their ends and their means. From our focus on the role of positive interactions in control processes, we introduce a novel mathematical modeling framework that tracks how individual cell lineages arise, and how the many layers of control break down in the emergence of cancer. The next generation of therapies must continue to look beyond cancers as being created by individual renegade cells and address not only the network of interactions those cells inhabit, but the evolutionary logic that created those interactions and their intrinsic vulnerability.

Keywords: cancer, invasive species, ecology, evolution, mathematical model

1. Introduction

A growing literature examines cancer from an ecological and evolutionary perspective [1]. The many parallels begin from two key ecological observations: individuals interact with each other and with their environment in the “ecological theater” [2], and individuals differ in ways that alter the outcome of those interactions [3]. Differences among individuals are the raw material for evolution, and interactions with other cells are the most important part of the selective environment [4]. Modern techniques have revealed the key role of heterogeneity within tumors [3]. High heterogeneity can make tumors more likely to progress, in part because there is more variation available for selection [5, 6, 7]. Indeed, genome instability has joined the ranks of “enabling characteristics” among the influential hallmarks of cancer [8]. The dynamic nature of this ecological and evolutionary process requires us to rethink treatment strategies as a game between physicians and an ever-changing opponent [9, 10].

Ecological theory has shifted from a focus on closed systems, such as succession within a single community, to the study of open systems with constant flows of resources and species. Ecological communities are seen as neither tightly coevolved nor tightly organized, but rather as assemblages of species that seem to work together [11]. Similarly, the tissues of our bodies are connected with each other and harbor many cells that fail to behave according to their fixed roles. and tissues have evolved to be robust against aberrant connections and cell deviations [12, 13]. But both tissues and communities remain vulnerable. Ecological communities can suffer devastating effects from invasive species [14], often used as an analogy with the escape of cancer cells from their fixed roles [9, 15].

The evolution of cancer has analogies with evolution within populations; it is a progressive process favoring rapidly replicating and persistently surviving cells [16]. But there is a fundamental difference: cell fitness results from the functioning of the entire system, with selection on the fitness of individual cells effectively suppressed in somatic tissue. In fact, the body works best when it minimizes evolution [17].

Here we examine and challenge the analogies between ecology and cancer. We consider how highly regulated cell systems, finely-tuned machines that rarely fail but do so catastrophically, differ from ecological systems that must tolerate high variability, and conclude with implications for therapy.

2. Cancer and invasive species

Biological invasions, in which a new species enters an existing community, occur in several steps including transport, colonization, establishment, and spread. The process is likely to fail at each step [15] and a successful invasion is perhaps the least likely outcome of an introduction [14]. Introduction often creates a genetic bottleneck and the ensuing evolutionary response to novel environments is constrained by that initial diversity [18]. Cancers parallel this broad picture. A newly evolved lineage of cancer cells is even less likely to survive the steps of invasion: intravasation, circulation and survival, extravasation, establishment, and angiogenesis [15, 19]. Success requires evolutionary responses to novel challenges despite the lack of genetic diversity when the lineage emerged.

Many biological invasions have a lag before spread [14]. Possible causes including simple stochasticity, the Allee effect where a species requires a critical mass of individuals to grow [20], and the potentially slow process of evolutionary or behavioral adaptation to a novel environment. In cancers, a period of dormancy can occur for similar reasons. This period often does not end; a large number of people carry dormant cancers that never progress [21]. Recent evidence has revealed one fundamental difference between the early phases of cancers and biological invasions. Biological invasions typically actively spread from their boundary, while metastases appear to be generated early and remain dormant for a long time even while the main tumor is progressing [22, 23]. Dormancy may be broken by many factors including local disturbance [24], senescence of non-cancerous cells that were initially better adapted to their microenvironment [5], or release of a proliferative signal from the primary site [19, 23].

Invasion ecology began by seeking to identify the characteristics of species that become successful invaders. While it seemed that successful invaders should have high fecundity and dispersal [25], it has proven nearly impossible the predict the outcome of invasion from a species’ traits [14]. Indeed, the most consistent predictor is a history of past invasions. Similarly, it remains difficult to predict which precancerous cells will eventually become invasive [26], while the fact of multiple metastasis from a single tumor argues that a history of past invasion predicts future invasion.

The second challenge for invasion ecology is to predict which ecological communities are prone to invasion. The original answer based on the notion of biotic resistance, that diverse communities are less likely to be invaded due to more efficient resource use or the lack of “empty niches,” has received mixed support at best [14]; numerous studies show the opposite effect [27]. We do not know of research on this in cancer, whether tissues with more diverse cell types are more resistant to cancer or metastasis. It has been suggested that disturbance creates pools of unused resources needed by invaders in ecology [25] or in cancer [28] or opens up other opportunities for invasion [29]. This too has not been generally demonstrated. Indeed, the causal arrow itself has been questioned, with invaders possibly creating disturbance rather than vice versa.

Individuals at the expanding border of an invasion or tumor have different environments, histories, and selective pressure from those closer to the center. Those with higher dispersal ability are sometimes found at the range boundaries [25]. However, selection for dispersal might be stronger near the center of the range where competition is strong. We share the view that dispersal is a real trait of organisms, favored by natural selection, while metastasis is merely a consequence of local movement within a tumor and invasion around it [15].

Because of the differences between cancer and ecological invasions, we suggest that many cancers (with the exception of transmissible cancers [30]), are less like invasive species than like native species that have escaped control. Indigenous weeds do not have to overcome dispersal barriers and have a shared evolutionary history with other native species [31], as do cancer cells with their healthy neighbors. A new continent may be far more novel than a new tissue, where cells share similar sizes, genetic expression and overall immune profile [15]. Cancers can also be compared to crop-derived invasives, which escape from their coddled environment and lose traits favored in crops such as low “shattering” (seed dispersal at maturity) [25]. In the same way, cancer cells escape the domestication of their well-regulated tissue. The escape from control that characterizes cancer cells is thus less like the novelty that allows an invasive species to succeed, but more a breakdown of delicately balanced control mechanisms.

3. Cancer and ecology: The role of positive interactions

Ecological populations are regulated by local biotic and resource interactions which have coevolved in current and past communities. Cell regulation in healthy tissues is in many ways similar. Competition for oxygen and glucose parallels exploitation competition for resources, and control by the immune system parallels control by natural enemies. Other interactions among cells have ecological analogues; antigrowth factors act like allelochemicals, and contact inhibition functions like interference competition or territoriality [8].

Within the body, cells work together. The plethora of positive interactions also have ecological parallels. Mutualists in both systems, frequently fungi in ecology and cells from the immune system or other regulatory systems in the body, can enhance access to resources or growth factors and suppress antigrowth factors or immune cells. Individuals create public goods, through recruitment of generalist mutualists, direct enhancement of resource supply, or protection, that benefit the collective [32].

We argue that the network of negative and positive interactions that characterize tissue regulation underlies both the robustness of the system and its vulnerability, and that positive interactions among cancer cells themselves play a secondary role. After heterogeneity builds up, positive interactions among cells are unlikely and their rarity could explain why most tumors fail to develop at all [33]. Complementation, where different cells express different cancer hallmarks, could be the most common positive interaction, and the most likely emerge early in a tumor [20].

Examples of positive interactions among cancer cells include overexpression of IL-11 by a small number cells that aid the majority that express FIGF [3], and a related system where IL-11 lineages increase the growth of other cells through mediation by the tumor microenvironment [34]. Exosomes transport compounds between cells, and are involved in cancer pathways ranging from the response to hypoxia and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to metastasis [35]. That cancer cells do not fully lose apoptotic pathways argues for a social role of even this hallmark of cancer, perhaps promoting cancer progression by opening up space for more aggressive cells [36].

Like all cells, the life of a cancer cell is determined by its array of interactions with surrounding cells. Tumors recruit endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts and macrophages among many others [24] that can activate the wound healing and the tissue remodeling that support invasion [19]. The immune cells that play these roles are thus a double-edged sword, by fighting cancer but promoting growth, and by releasing factors that down-regulate its own ability to fight cancer [5]. The “one-renegade cell” model fails to appreciate this ecological context [37]. In the most radical view, the environment could reconstitute an entire tumor even after its complete destruction [13].

4. A modeling approach

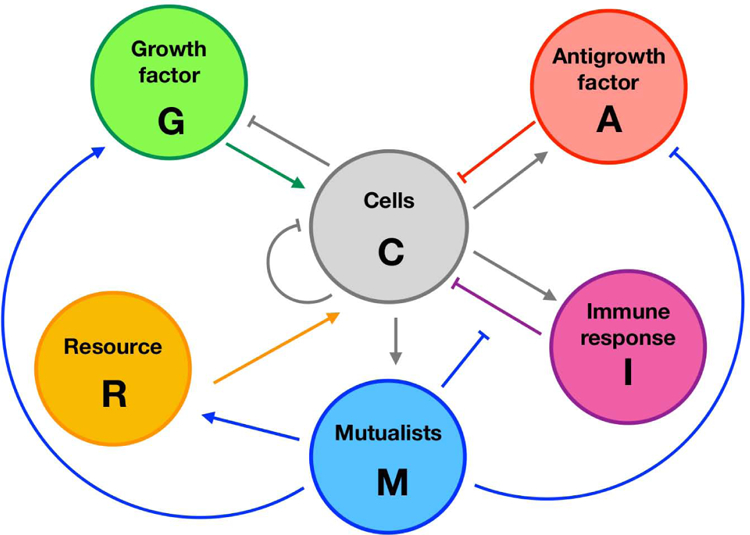

We have developed a minimal modeling framework to capture the ecoevolutionary progress of cancers from initiation to escape, and to contrast with ecological invasion and spread. Cells interact with five elements of their environment (Figure 1).

Growth factor G that promotes growth,

Anti-growth factor A that reduces growth,

Resources R that are essential for growth,

Immune cells I that can control aberrant lines,

Mutualist cells M that can enhance growth through recruitment of growth factor or resource, or by suppression of anti-growth factor or immunity.

Figure 1:

Strategic diagram of cancer interactions. Arrows indicate activation and flat-headed segments inhibition.

We model evolution as changes in the parameter values that quantify interactions of cancer cells with each other and with their environment, tracking a variable number of cell lineages as they are generated by mutation or lost to extinction. Control is implemented through oncogene-induced senescence [38] that increases death rates in cells that grow too aggressively, and by immune removal of cells that differ significantly from the initial type. Starting with a population entirely of normal cells, the system generates numerous novel lineages that mirror normal cell variation but can escape and grow if control systems are weak or break down (Figure 2).

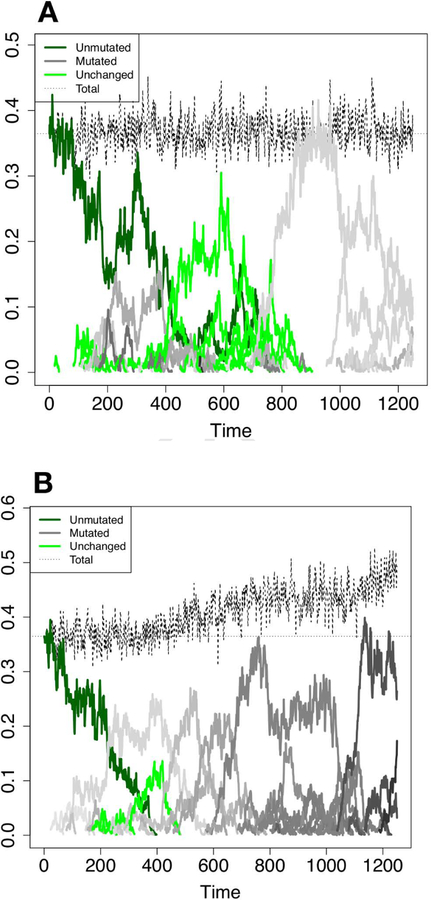

Figure 2:

Model populations of all cell lineages showing high degrees of cell turnover but constant overall population with strong control (A) and steadily increasing population with weak control (B). The dark green line shows the population of unaltered cells, the bright green lines cells altered in aspects that do not directly affect fitness, and darker gray lines cells with traits increasingly different from the original type.

In the model, two interacting processes enable escape from control: a breakdown of the enforcement mechanisms and the cooption of mutualists (Figure 3). After weakening of the enforcement system, precancerous cells can enlist mutualists to further enhance growth, often through public goods that do not benefit any particular lineage but which may create the permissive environment for a positive feedback involving tumor heterogeneity. The observation that healthy tissue harbors many mutations that resemble those in cancer [39] coupled with the difficulty of predicting which of those cells will eventually become dangerous [26] argues for the multistage complexity of the escape process.

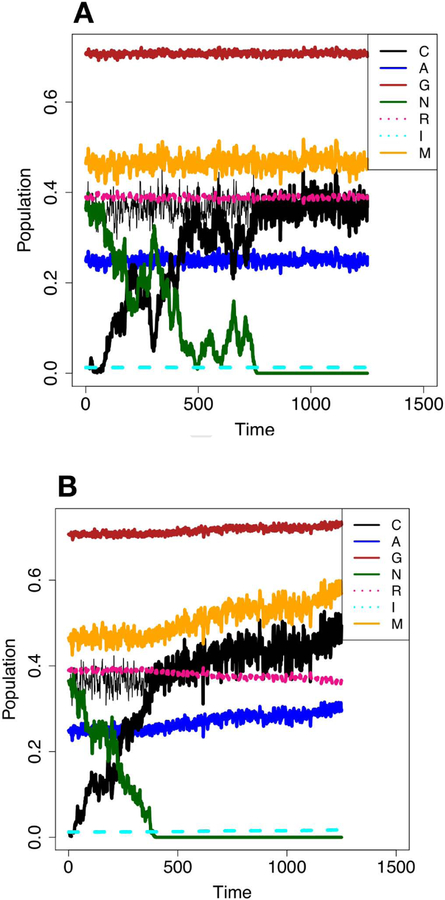

Figure 3:

Populations of all model elements in the conditions of strong control (A) and weak control (B) as in Figure 2. Model elements as in Figure 1 with N representing normal or unaltered cells.

5. Implications for therapy

Ecological and evolutionary thinking has inspired innovative approaches to therapies that attack targets associated with fewer side effects, or that delay or evade resistance [21]. For example, cancers that rely upon positive interactions should respond to targeting of those mechanisms [20] or to attack on cells that support the cancer [40]. A “double bind” might be key to avoiding resistance, whereby resistance to one agent makes a cancer more vulnerable to a second [9].

Treatment strategies for cancer parallel those for invasive species [41].

Surgery and physical removal eliminate the most visible parts of the invasion, but rarely fully eradicate and must be complemented with other treatments. In addition to their beneficial effects, the inevitable disturbance from these methods has the potential to allow secondary invasions [23].

Chemotherapy and pesticides seek to kill only their targets, but their very effectiveness creates side effects through damage to non-target individuals, and strong selection for resistance.

Immunotherapy and biological control use the power and specificity of biology against itself, with extraordinary results when they work, but with a high frequency of unexplained failure, and need for combination with other therapies [9].

Treatments can have unintended consequences. Just as controlling one species can open up room for another [14], treatment can open up empty space that other more aggressive cells fill [7], or break the control of clonal interference, killing off the first clones and releasing fitter clones [42]. Similarly, reduction of diversity by treatment could unleash a new round of adaptive radiation [34]. Thinking only of the evolutionary response within tumor cells misses the role of the tumor microenvironment, which can promote many mechanisms of drug resistance [43]. Factors transported between cells can spread resistance beyond the original cell and evade the benefits of combination therapy [13]. Finally, resistance often emerges not through genetic evolution but through behavioral or epigenetic changes that might explain the frequency of resistance in metastases [19].

Plasticity may act like a functional bottleneck that removes types with the wrong phenotype [13]. Creative ways to capitalize on these alternative pathways, such as using exosomes to deliver drugs [35], might be key next steps in the game between physicians and cancer [10].

6. Final thoughts

Despite the many parallels, cancers differ fundamentally from both invasive species and evolving species. Control mechanisms in the body minimize invasion and evolution by suppressing fitness differences among cells in somatic tissues. Evolution, however, cannot be completely turned off. The exigencies of maintaining a metazoan lead to the following seemingly inescapable logic. Life is unpredictable, from both internal and external sources. Coping with these unpredictable insults and errors requires excess capacity. Activating this excess capacity requires regeneration and reprogramming of individual units, a process that necessarily generates genetic and phenotypic errors. Excess capacity must be regulated between insults, and turned off after a problem has been addressed. Effective regulation in turn allows for more excess capacity to address problems more quickly. This network of regulation, however, is vulnerable to the very excess capacity it allows. When regulation fails, excess capacity can create catastrophic system breakdown, such as in cancer and autoimmune disease. The ecology of cancer is the ecology of this regulatory network, and our treatment strategies for cancer must move beyond thinking of cancer cells as “cheaters” but rather as one part of a systemic breakdown of regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrea Bild, Jason Griffiths and Joel Brown for useful discussions.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant number 7U54CA209978–02, and the Modeling the Dynamics of Life fund at the University of Utah.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Anderson AR, Maini PK, Mathematical oncology, Bull. Math. Biol 80 (2018) 945–953 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Crespi BJ, Summers K, Evolutionary biology of cancer, Trends Ecol. Evol 20 (2005) 545–552 (2005).● Creative and influential insights into the evolution of cancer

- [3].Tabassum DP, Polyak K, Tumorigenesis: it takes a village, Nat. Rev. Cancer 15 (2015) 473–483 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Maley CC, Aktipis A, Graham TA, Sottoriva A, Boddy AM, Janiszewska M, Silva AS, Gerlinger M, Yuan Y, Pienta KJ, Anderson KS, Gatenby R, Swanton C, Posada D, Wu C-I, Schiffman JD, Hwang ES, Polyak K, Anderson ARA, Brown JS, Greaves M, Shibata D, Classifying the evolutionary and ecological features of neoplasms, Nat. Rev. Cancer 17 (2017) 605–619 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kareva I, What can ecology teach us about cancer?, Translational Oncology 4 (2011) 266–270 (2011).● Clear exposition of ecological approaches to cancer, with interesting links to invasion biology and extinction dynamics.

- [6].Maley CC, Galipeau PC, Finley JC, Wongsurawat VJ, Li X, Sanchez CA, Paulson TG, Blount PL, Risques RA, Rabinovitch PS, Reid BJ, Genetic clonal diversity predicts progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, Nat. Genet 38 (2006) 468–473 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC, Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process, Nat. Rev. Cancer 6 (2006) 924–935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation, Cell 144 (2011) 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gatenby RA, Brown J, Vincent T, Lessons from applied ecology: cancer control using an evolutionary double bind, Cancer research 69 (2009) 7499–7502 (2009).●● Important application of key ideas from evolutionary biology to cancer therapy, introducing the double bind idea.

- [10].Staňková K, Brown JS, Dalton WS, Gatenby RA, Optimizing cancer treatment using game theory: A review, JAMA Oncology 5 (2018) 96–103 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mittelbach GG, Schemske DW, Ecological and evolutionary perspectives on community assembly, Trends Ecol. Evol 30 (2015) 241–247 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Plutynski A, Bertolaso M, What and how do cancer systems biologists explain?, Philosophy of Science 85 (2018) 942–954 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rosenbloom DI, Camara PG, Chu T, Rabadan R, Evolutionary scalpels for dissecting tumor ecosystems, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer 1867 (2017) 69–83 (2017).● Very original approach to tumor heterogeneity emphasizing the structure of the tumor as an organ rather than a less organized ecosystem, emphasizing the importance of plasticity and cell communication in regulation.

- [14].Mack RN, Simberloff D, Lonsdale WM, Evans H, Clout M, Bazzaz FA, Biotic invasions: Causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control, Ecol. Appl 10 (2000) 689–710 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lloyd MC, Gatenby RA, Brown JS, Ecology of the metastatic process, in: Ujvari B, Roche B, Thomas F (Eds.), Ecology and Evolution of Cancer, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 153–165 (2017).●● Perhaps the best overview of the comparison of cancers with invasive species, particularly strong on the mechanisms and role of movement in the two systems.

- [16].Nowell PC, The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations, Science 194 (1976) 23–28 (1976).● Seminal paper introducing evolutionary thinking into cancer biology.

- [17].Basanta D, Anderson ARA, Exploiting ecological principles to better understand cancer progression and treatment, Interface Focus 3 (2013) 20130020 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schrieber K, Lachmuth S, The genetic paradox of invasions revisited: the potential role of inbreeding×environment interactions in invasion success, Biological Reviews 92 (2017) 939–952 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Riggi N, Aguet M, Stamenkovic I, Cancer metastasis: A reappraisal of its underlying mechanisms and their relevance to treatment, Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 13 (2018) 117–140 (2018).● Outstanding review of metastatic mechanisms, with particularly interesting discussion of dormant cells.

- [20].Korolev KS, Xavier JB, Gore J, Turning ecology and evolution against cancer, Nature Reviews Cancer 14 (2014) 371–380 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kareva I, Cancer ecology: Niche construction, keystone species, ecological succession, and ergodic theory, Biological Theory 10 (2015) 283–288 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [22].Klein CA, Holzel D, Systemic cancer progression and tumor dormancy: mathematical models meet single cell genomics, Cell Cycle 5 (2006) 1788–1798 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wikman H, Vessella R, Pantel K, Cancer micrometastasis and tumour dormancy, Apmis 116 (2008) 754–770 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Joyce JA, Pollard JW, Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis, Nat. Rev. Cancer 9 (2009) 239 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hodgins KA, Bock DG, Rieseberg LH, Trait evolution in invasive species, Annual Plant Reviews online 1 (2018) 1–37 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thomas F, Fisher D, Fort P, Marie J-P, Daoust S, Roche B, Grunau C, Cosseau C, Mitta G, Baghdiguian S, et al. , Applying ecological and evolutionary theory to cancer: a long and winding road, Evolutionary Applications 6 (2013) 1–10 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Stohlgren TJ, Barnett DT, Kartesz JT, The rich get richer: patterns of plant invasions in the United States, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 1 (2003) 11–14 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ducasse H, Arnal A, Vittecoq M, Daoust SP, Ujvari B, Jacque-line C, Tissot T, Ewald P, Gatenby RA, King KC, et al. , Cancer: An emergent property of disturbed resource-rich environments? Ecology meets personalized medicine, Evolutionary Applications 8 (2015) 527–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Daoust SP, Fahrig L, Martin AE, Thomas F, From forest and agro-ecosystems to the microecosystems of the human body: what can landscape ecology tell us about tumor growth, metastasis, and treatment options?, Evolutionary Applications 6 (2013) 82–91 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ujvari B, Gatenby RA, Thomas F, The evolutionary ecology of transmissible cancers, Infection, Genetics and Evolution 39 (2016) 293–303 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Catford JA, Jansson R, Nilsson C, Reducing redundancy in invasion ecology by integrating hypotheses into a single theoretical framework, Diversity and Distributions 15 (2009) 22–40 (2009).● Comprehensive review of theories of invasive species, with useful summaries of their underlying commonalities.

- [32].Kaznatcheev A, Peacock J, Basanta D, Marusyk A, Scott JG, Fibroblasts and Alectinib switch the evolutionary games played by non-small cell lung cancer, Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (2019) 450–456 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Archetti M, Pienta KJ, Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to cancer, Nat. Rev. Cancer (2018) 1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Marusyk A, Tabassum DP, Altrock PM, Almendro V, Michor F, Polyak K, Non-cell-autonomous driving of tumour growth supports subclonal heterogeneity, Nature 514 (2014) 54–58 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Azmi AS, Bao B, Sarkar FH, Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: a comprehensive review, Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 32 (2013) 623–642 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Labi V, Erlacher M, How cell death shapes cancer, Cell Death & Disease 6 (2016) e1675 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nagy JD, The ecology and evolutionary biology of cancer: a review of mathematical models of necrosis and tumor cell diversity, Math. Biosci. Eng 2 (2005) 381–418 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sherr CJ, Weber JD, The ARF/p53 pathway, Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 10 (2000) 94–99 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, Wedge DC, Fullam A, Alexandrov LB, Tubio JM, et al. , High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin, Science 348 (2015) 880–886 (2015).● Fascinating data on mutations in normal cells that parallel some characteristics of cancer.

- [40].Pienta KJ, McGregor N, Axelrod R, Axelrod DE, Ecological therapy for cancer: defining tumors using an ecosystem paradigm suggests new opportunities for novel cancer treatments, Translational Oncology 1 (2008) 158–164 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Amend SR, Pienta KJ, Ecology meets cancer biology: the cancer swamp promotes the lethal cancer phenotype, Oncotarget 6 (2015) 9669 (2015).● Great metaphor of cancer swamp and comprehensive list of parallels of cancer with ecology.

- [42].Robertson-Tessi M, Anderson AR, Big Bang and context-driven collapse, Nature Genetics 47 (2015) 196–197 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li Z-W, Dalton WS, Tumor microenvironment and drug resistance in hematologic malignancies, Blood Reviews 20 (2006) 333–342 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]