Since the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002, the emergence and expansion of endemic and epidemic coronaviruses has been accelerating on a scale not seen for any other group of viruses with pandemic potential. In the past two decades alone, five new human coronaviruses have been discovered, three of which are highly pathogenic.1, 2 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is just the latest example of the danger posed by zoonotic diseases, foreshadowed by the regional, but unabated, emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).3 In recognition of its intrinsic threat to public health and as a prototypical member of the family Coronaviridae, WHO, in 2015, prioritised MERS-CoV as a pathogen to which increased resources should be dedicated for countermeasure research and development. The newly established Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations followed suit with investments in the development of candidate MERS-CoV vaccines.4 In subsequent years, three vaccine candidates have completed initial clinical evaluation and are now ready for advanced testing.5, 6, 7, 8, 9

In The Lancet Infectious Diseases, two groups8, 9 report results from phase 1 clinical trials of non-replicating viral vector MERS-CoV vaccines. Pedro Folegatti and colleagues8 summarise the safety and immunogenicity of a chimpanzee adenovirus-vectored vaccine, ChAdOx1 MERS, and Till Koch and colleagues9 do the same for a poxvirus-vectored vaccine, MVA-MERS-S. The two vaccines demonstrated tolerable safety profiles (no vaccine-related serious adverse events were reported for either vaccine) and induced humoral and cellular immune responses at peak, post-vaccination timepoints. ChAdOx1 MERS was administered as a single injection, whereas MVA-MERS-S was given as a two-dose regimen, with a 28-day interval between doses. Both products were tested in a dose-escalating design. Although the frequency and severity of adverse events were proportional to vaccine dose in both studies, only higher doses of ChAdOx1 MERS improved immunogenicity. A single dose of ChAdOx1 MERS also showed an earlier ascent and slower decay of antibody-mediated and cell-mediated immunity than two doses of MVA-MERS-S. While noting that binding antibody levels are reported differently between these studies, a single dose of ChAdOx1 MERS vaccine induced detectable antibody titres at day 180 (in 18 [75%] of 24 participants) and day 364 (13 [68%] of 19 participants) after vaccination, whereas with MVA-MERS-S only three (14%) of 22 vaccine recipients had detectable antibody titres at day 180.

Differences in the magnitude, kinetics, and character of the elicited immune responses raise common concerns for the development pathway of outbreak vaccines against MERS-CoV and, more acutely, SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Interrogation of the humoral and cellular immune profiles of the vaccine candidates highlights the first point: what immune responses do coronavirus vaccines need to elicit to confer protection against infection or severe disease? Although the question is applicable to many viruses, the answer to this question has been elusive among coronaviruses.10, 11 Without previous identification of a potential correlate of protection, it becomes difficult to ascertain the relevance of immunogenicity outputs. Second, there remains a lack of consensus on the methodology by which immunogenicity outputs are measured.12 Although the two trials report similar assessments of humoral responses—binding antibody, wild-type MERS virus, and pseudovirus neutralisation assays—it is difficult to know how these individual results compare between studies. Koch and colleagues9 found a strong correlation between binding and neutralising antibody titres (Spearman's correlation r=0·86 [95% CI 0·6960–0·9427], p=0·0001), whereas Folegatti and colleagues8 did not (Spearman's r=0·28, p=0·175). Does this represent an immunologically relevant difference between vaccine-induced responses or a methodological difference between laboratories? Finally, some animal studies suggest that certain SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV vaccines might, upon viral challenge, be associated with eosinophilic pulmonary infiltrates. This finding underscores the importance of factoring safety into the design, monitoring, and long-term follow-up of coronavirus vaccine trials—something that cannot be fully addressed in the two early-stage MERS vaccine trials herein, but which will undoubtedly be considered in future efficacy trials.

The experience with SARS and the emergence of MERS, particularly during the outbreaks of 2014–15 in the Arabian and Korean peninsulas, were harbingers of the consequences of COVID-19, and similar pathogens, on all sectors of society—not only in overall morbidity and mortality, but also in the capacity to level economies and disrupt social order.13 If MERS has been eclipsed by its pandemic cousin, then the lessons learned have prepared the global vaccine research and development community for moving coronavirus vaccines forward at an accelerated pace, such that first-in-human COVID-19 vaccine trials are moving on unprecedented, shortened timelines. To stay ahead of these increasingly frequent outbreaks, the field must maintain momentum in advancing rapid, scalable, and translatable vaccine strategies, not only for MERS-CoV, but even more urgently for SARS-CoV-2 and, ultimately, the next novel coronavirus that leaps from its animal host to humans.

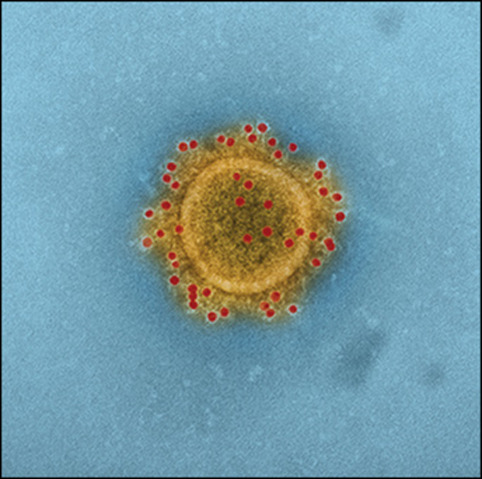

© 2020 Flickr - NIAID

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests. This Comment is the opinion of the authors and should not be construed as official or reflecting the views of the US Government, the Department of Defense, or the Department of the Army.

References

- 1.Ar Gouilh M, Puechmaille SJ, Diancourt L. SARS-CoV related Betacoronavirus and diverse Alphacoronavirus members found in western old-world. Virology. 2018;517:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Memish ZA, Perlman S, Van Kerkhove MD, Zumla A. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2020;395:1063–1077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plotkin SA. Vaccines for epidemic infections and the role of CEPI. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13:2755–2762. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1306615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alharbi NK, Qasim I, Almasoud A. Humoral Immunogenicity and efficacy of a single dose of ChAdOx1 MERS vaccine candidate in dromedary camels. Sci Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52730-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haagmans BL, van den Brand JM, Raj VS. An orthopoxvirus-based vaccine reduces virus excretion after MERS-CoV infection in dromedary camels. Science. 2016;351:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modjarrad K, Roberts CC, Mills KT. Safety and immunogenicity of an anti-Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus DNA vaccine: a phase 1, open-label, single-arm, dose-escalation trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30266-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folegatti PM, Bittaye M, Flaxman A. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus viral-vectored vaccine: a dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, uncontrolled, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30160-2. published online April 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koch T, Dahlke C, Fathi A. Safety and immunogenicity of a modified vaccinia virus Ankara vector vaccine candidate for Middle East respiratory syndrome: an open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30248-6. published online April 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Channappanavar R, Zhao J, Perlman S. T cell-mediated immune response to respiratory coronaviruses. Immunol Res. 2014;59:118–128. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao J, Alshukairi AN, Baharoon SA. Recovery from the Middle East respiratory syndrome is associated with antibody and T-cell responses. Sci Immunol. 2017;2 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aan5393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SW, Perera RA, Choe PG. Comparison of serological assays in human Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-coronavirus infection. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.41.30042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joo H, Maskery BA, Berro AD, Rotz LD, Lee YK, Brown CM. Economic impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on the Republic of Korea's tourism-related industries. Health Secur. 2019;17:100–108. doi: 10.1089/hs.2018.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]