Abstract

Proper management of COVID-19 mandates better understanding of disease pathogenesis. The sudden clinical deterioration 7–8 days after initial symptom onset suggests that severe respiratory failure (SRF) in COVID-19 is driven by a unique pattern of immune dysfunction. We studied immune responses of 54 COVID-19 patients, 28 of whom had SRF. All patients with SRF displayed either macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) or very low human leukocyte antigen D related (HLA-DR) expression accompanied by profound depletion of CD4 lymphocytes, CD19 lymphocytes, and natural killer (NK) cells. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) production by circulating monocytes was sustained, a pattern distinct from bacterial sepsis or influenza. SARS-CoV-2 patient plasma inhibited HLA-DR expression, and this was partially restored by the IL-6 blocker Tocilizumab; off-label Tocilizumab treatment of patients was accompanied by increase in circulating lymphocytes. Thus, the unique pattern of immune dysregulation in severe COVID-19 is characterized by IL-6-mediated low HLA-DR expression and lymphopenia, associated with sustained cytokine production and hyper-inflammation.

Keywords: dysregulation, interleukin-6, monocytes, lymphopenia, HLA-DR, ferritin, macrophage activation, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, respiratory failure

Graphical Abstract

Proper management of COVID-19 mandates better understanding of disease pathogenesis. Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al. describe two main features preceding severe respiratory failure associated with COVID-19: the first is macrophage activation syndrome; the second is defective antigen-presentation driven by interleukin-6. An IL-6 blocker partially rescues immune dysregulation in vitro and in patients.

Introduction

In December 2019, authorities in Wuhan, China reported a cluster of pneumonia cases caused by an unknown etiologic agent. The pathogen was soon identified and sequenced as a novel coronavirus related to the agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and was subsequently termed SARS Coronavirus-19 (SARS-CoV-2). The infection spread in the subsequent 3 months on all continents and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. As of April 2, 2020, 961,818 documented cases were reported worldwide, and 49,165 patients had died (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). This novel coronavirus has a tropism for the lung, causing community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). Some patients with pneumonia suddenly deteriorate into severe respiratory failure (SRF) and require intubation and mechanical ventilation (MV). The risk of death of these patients is high, reaching even 60% (Arabi et al., 2020).

Proper management mandates better understanding of disease pathogenesis. The majority of physicians use sepsis as a prototype of critical illness for the understanding of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pathogenesis. This is mostly because severe COVID-19 is associated with hyper-cytokinemia (Guan et al., 2020, Huang et al., 2020). Lethal sepsis is commonly arising from bacterial CAP, often leading to SRF and the need for MV. The peculiar clinical course of CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2, including the sudden deterioration of the clinical condition 7–8 days after the first symptoms, generates the hypothesis that this illness is driven by a unique pattern of immune dysfunction that is likely different from sepsis. The features of lymphopenia with hepatic dysfunction and increase of D-dimers (Qin et al., 2020) in these patients with severe disease further support this hypothesis.

Immune responses of critically ill patients with sepsis can be classified into three patterns: macrophage-activation syndrome (MAS) (Kyriazopoulou et al., 2017), sepsis-induced immunoparalysis characterized by low expression of the human leukocyte antigen D related (HLA-DR) on CD14 monocytes (Lukaszewicz et al., 2009), and an intermediate functional state of the immune system lacking obvious dysregulation. We investigated whether this classification might apply to patients with SRF caused by SARS-CoV-2. Results revealed that approximately one fourth of patients with SRF have MAS and that most patients suffer from immune dysregulation dominated by low expression of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes, which is triggered by monocyte hyperactivation, excessive release of interleukin-6 (IL-6), and profound lymphopenia. This pattern is distinct from the immunoparalysis state reported in either bacterial sepsis or SRF caused by 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Results

All Patients with Severe Respiratory Failure Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Have Immune Dysregulation or MAS

We assessed the differences of immune activation and dysregulation between SARS-CoV-2 and other known severe infections in three patient cohorts: 104 patients with sepsis caused by bacterial CAP; 21 historical patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza; and 54 patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2. Patients with bacterial CAP were screened for participation in a large-scale randomized clinical trial with the acronym PROVIDE (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03332225). Patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza have been described in previous publications of our group (Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al., 2009, Raftogiannis et al., 2010). The clinical characteristics of patients with bacterial CAP and CAP caused by COVID-19 are described in Table 1 . Each cohort (bacterial sepsis and COVID-19) is split into patients who developed SRF and required MV and those who did not. Three main features need to be outlined: (1) patients with COVID-19 and SRF are less severe than those with severe bacterial CAP, on the basis of the traditional severity scores of sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) and acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) II; (2) this leads to the conclusion that COVID-19 patients undergo an acute immune dysregulation with deterioration into SRF before the overall state of severity is advanced; and (3) although the burden of co-morbidities of patients with COVID-19, as expressed by the Charlson’s co-morbidity index, is higher among patients with SRF than among patients without SRF, it remains remarkably lower that traditional bacterial CAP and sepsis. It was also notable that the admission values of Glasgow Coma Scale scores of patients with bacterial CAP were 8.80 ± 4.76, and that of patients with COVID-19 was 14.71 ± 0.20 (p < 0.0001). This finding is fully compatible with clinical descriptions of severe COVID-19: patients are admitted at a relatively good clinical state and suddenly deteriorate.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of the Cohorts of Bacterial CAP and of Pneumonia Caused by SARS-CoV-2

| No respiratory failure |

Severe respiratory failure |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | SARS-CoV-2 | p value | Bacterial | SARS-CoV-2 | p value | |

| Number of patients | 48 | 26 | 56 | 28 | ||

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 74.8 ± 16.8 | 59.2 ± 10.3 | <0.0001 | 74.0 ± 12.6∗ | 67.8 ± 10.8# | <0.0001 |

| Male gender (n, %) | 25 (52.1) | 15 (57.7) | 0.807 | 27 (48.2)∗ | 25 (89.3)∗∗ | 0.0003 |

| APACHE II score (mean ± SD) | 18.50 ± 8.19 | 5.88 ± 3.40 | <0.0001 | 26.63 ± 8.52∗∗ | 10.17 ± 3.64## | <0.0001 |

| SOFA score (mean ± SD) | 7.87 ± 3.81 | 1.50 ± 0.82 | <0.0001 | 11.46 ± 3.15∗∗ | 5.71 ± 2.19## | <0.0001 |

| CCI (mean ± SD) | 5.53 ± 2.13 | 2.16 ± 1.46 | <0.0001 | 5.57 ± 2.20∗ | 3.39 ± 2.16## | <0.0001 |

| PSI (mean ± SD) | 146.5 ± 43.2 | 80.0 ± 30.7 | <0.0001 | 177.4 ± 40.4∗∗∗ | 121.2 ± 28.3## | <0.0001 |

| Laboratory values (mean ± SD) | ||||||

| Total white blood cell count (/mm3) | 13,852.7 ± 7279.3 | 6379.6 ± 1993.9 | <0.0001 | 17,666.9 ± 12,799.9∗ | 9447.8 ± 3308.6## | <0.0001 |

| Absolute platelet count (x103 /mm3) | 201.3 ± 124.8 | 243.8 ± 109.1 | 0.141 | 224.3 ± 111.0∗ | 213.9 ± 71.8∗ | 0.654 |

| INR | 1.28 ± 0.64 | 1.11 ± 0.15 | 0.187 | 1.33 ± 0.45∗ | 1.17 ± 0.20∗ | 0.077 |

| aPTT (secs) | 37.19 ± 12.95 | 33.40 ± 6.22 | 0.165 | 38.42 ± 23.00∗ | 37.52 ± 9.88∗ | 0.844 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 475.6 ± 196.3 | 528.9 ± 152.5 | 0.234 | 495.3 ± 290.5∗ | 693.5 ± 188.6# | 0.002 |

| D-dimers (g/dl) | 7.66 ± 13.9 | 2.76 ± 2.02 | 0.079 | 1.46 ± 1.62∗∗ | 5.43 ± 6.41∗ | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.55 ± 1.00 | 0.85 ± 0.19 | 0.001 | 1.71 ± 0.90∗ | 1.11 ± 0.43# | 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.43 ± 1.92 | 0.67 ± 0.50 | 0.052 | 1.17 ± 1.88∗ | 0.97 ± 0.68∗ | 0.588 |

| AST (U/l) | 155.1 ± 308.1 | 39.9 ± 28.5 | 0.062 | 311.7 ± 748.2∗ | 76.6 ± 59.2# | 0.102 |

| ALT (U/l) | 234.6 ± 764.3 | 40.2 ± 24.9 | 0.200 | 175.8 ± 378.0∗ | 64.3 ± 62.2∗ | 0.126 |

| Main comorbidities (n, %) | ||||||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 13 (27.1) | 4 (15.4) | 0.386 | 21 (37.5)∗ | 6 (21.4)∗ | 0.214 |

| Chronic heart failure | 8 (16.7) | 3 (11.5) | 0.737 | 18 (32.1)∗ | 4 (14.3)∗ | 0.114 |

| Coronary heart disease | 7 (14.6) | 2 (7.7) | 0.479 | 10 (17.9) | 5 (17.9)∗ | 1.0 |

Comparisons with the respective groups without respiratory failure by the Student’s t test: ∗p-non-significant; ∗∗p < 0.05; #p < 0.001; ##p < 0.0001. Abbreviations are as follows: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; CCI, Charlson’s comorbidity index; INR, international normalized ratio; PSI, pneumonia severity index; SD, standard deviation; SOFA, sequential organ failure assessment

Immune classification of patients with SARS-CoV-2 was performed by using the tools suggested for bacterial sepsis, i.e., ferritin more than 4,420 ng/mL for MAS (Kyriazopoulou et al., 2017), and HLA-DR molecules on CD14 monocytes lower than 5,000, in the absence of elevated ferritin, for the immune dysregulation phenotype (Lukaszewicz et al., 2009). It was found that contrary to the patients with bacterial CAP and SRF, all patients with SRF and SARS-CoV-2 had either immune dysregulation or MAS (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Association between Severe Respiratory Failure and Immune Classification among Patients with COVID-19 and Patients with Sepsis Caused by Bacterial CAP

| Number of patients with SRF/total patients [%, (−95% CI, +95% CI)] |

p value∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial CAP | COVID-19 | ||

| Intermediate | 21/40 [52.5 (27.5-67.1)] | 0/26 [0 (0-12.9)] | <0.0001 |

| Immunoparalysis (for bacterial CAP) and immune dysregulation (for COVID-19) or MAS | 35/64 [54.7 (42.6-66.3)] | 28/28 [100 (87.9-100)] | <0.0001 |

∗comparisons by the Fisher exact test. Abbreviation is as follows: CI, confidence interval.

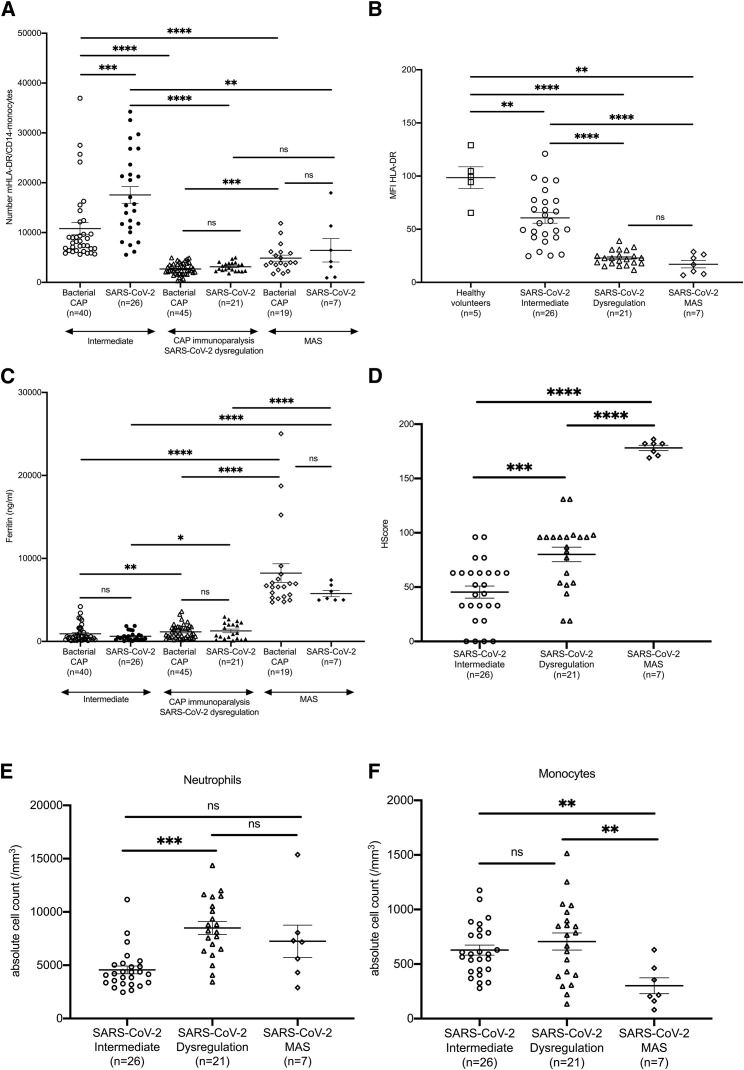

Major Decrease of HLA-DR on CD14 Monocytes Is Associated with SRF

Immunoparalysis of sepsis is characterized by significant decrease of the number of HLA-DR molecules on CD14 monocytes. This also happens in immune dysregulation caused by SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 1A and 1B). Although patients with bacterial-CAP-associated MAS also have decreased HLA-DR molecules on CD14 monocytes, their circulating ferritin is significantly higher than normal. This is a feature found only in a few patients with SARS-CoV-2 and MAS (Figure 1C). The absence of traits of MAS among cases of SARS-CoV-2 with immune dysregulation is further proven by the low scores of hemophagocytosis (HS). HScore is proposed as a classification tool for secondary MAS, and values more than 169 are highly diagnostic (Fardet et al., 2014). Seven patients with SARS-CoV-2 had HS above this cut-off, and all were properly classified by using ferritin (Figure 1D). Among patients with bacterial CAP at an intermediate immune state, the number of molecules of HLA-DR on their CD14 monocytes was lower than in healthy patients. However, patients with pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 at an intermediate immune state maintained their number of molecules of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes much closer to the healthy condition. When this number suddenly dropped, SRF supervened (Figures 1A and 1B). Moreover, the absolute counts of neutrophils and monocytes were higher among patients with immune dysregulation than patients with MAS (Figures 1E and 1F).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of Immune Dysregulation of COVID-19

(A) Absolute numbers of the molecules of the human leukocyte antigen (mHLA-DR) on CD14 monocytes. Patients with bacterial CAP and CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 are classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, immunoparalysis for bacterial CAP and dysregulation for COVID-19, and MAS.

(B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of healthy volunteers and of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified according to their state of immune activation.

(C) Ferritin concentrations in the serum of patients with bacterial CAP and sepsis and CAP caused by SAR-CoV-2 according to their state of immune activation.

(D) Hemophagocytosis score among patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified according to their state of immune activation.

(E) Absolute neutrophil counts among patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified according to their state of immune activation.

(F) Absolute monocyte counts among patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified according to their state of immune activation.

Bars in each graphic represent mean values and standard errors. Statistical comparisons are indicated by the arrows; ns: non-significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Comparisons were done by the Mann-Whitney U test followed by correction for multiple comparisons.

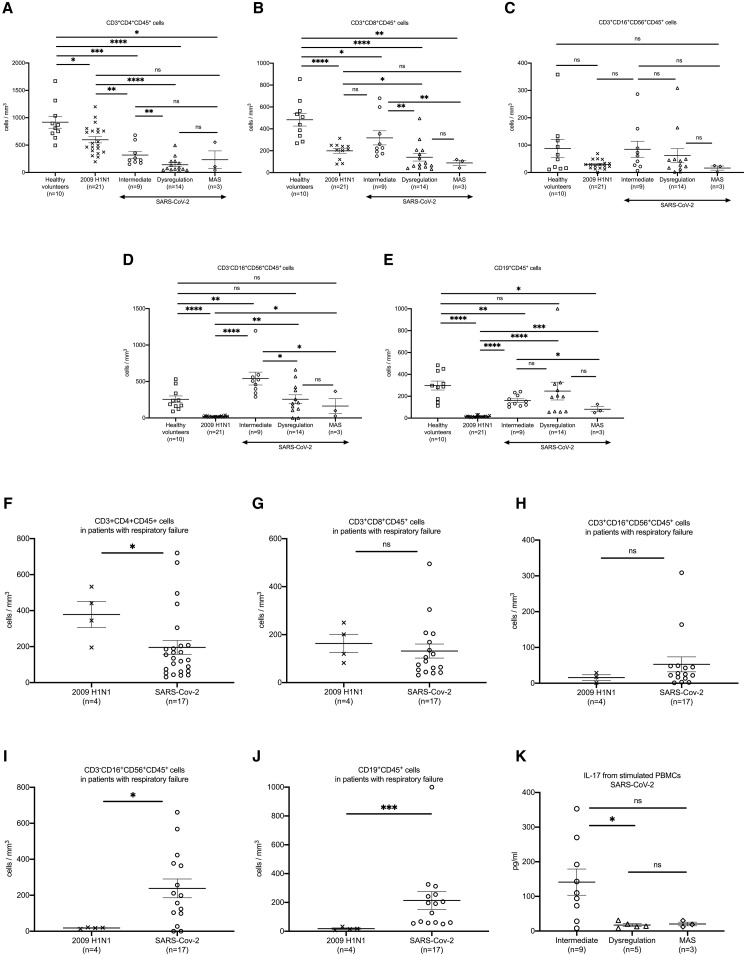

CD4 Cell and NK Cell Cytopenias Are Characteristics of Infection by SARS-CoV-2

The absolute counts of CD3+CD4+CD45+ lymphocytes, CD3+CD8+CD45+ lymphocytes, CD3−CD16+CD56+CD45+ cells, and CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes were lower among patients with COVID-19 compared with those in 10 healthy subjects adjusted for age and gender. Compared with patients with CAP caused by 2009H1N1, patients with COVID-19 had lower CD3+CD4+CD45+ lymphocytes but higher CD3+CD16+CD45+ cells and CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes (Figures 2A–2E). Those patients with immune dysregulation caused by COVID-19 had lower counts of CD3+ CD4+ CD45+ lymphocytes, CD3+CD8+CD45+ lymphocytes, and CD3−CD16+CD56+CD45+ cells than those at an intermediate immune state. When comparisons were limited to patients with SRF and infection by one of the two viruses, it was found that infection by SARS-CoV-2 was accompanied by lower CD3+CD4+CD45+ lymphocytes but with higher CD3−CD16+CD56+CD45+ cells and CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes than 2009H1N1 (Figures 2F–2J). The Th17 function as assessed by IL-17 production capacity was downregulated among patients with immune dysregulation (Figure 2K).

Figure 2.

CD4 Cell and NK Cell Cytopenias Are Characteristics of Infection by SARS-CoV-2

(A–E) Absolute counts of CD3+CD4+CD45+ lymphocytes (A), CD3+CD8+CD45+ lymphocytes (B), CD3+CD16+CD56+CD45+ lymphocytes (C), CD3−CD16+CD56+CD45+ cells (D), and CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes (E) among healthy volunteers, patients with CAP caused by the 2009H1N1 influenza virus, and patients with CAP caused by COVID-19. Patients with COVID-19 are classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation, and MAS.

(F–J) absolute counts of CD3+CD4+CD45+ lymphocytes (F), CD3+CD8+CD45+ lymphocytes (G), CD3+CD16+CD56+CD45+ lymphocytes (H), CD3−CD16+CD56+CD45+ cells (I), and CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes (J) among patients with severe respiratory failure developing in the field of CAP caused by the 2009H1N1 influenza virus and COVID-19.

(K) IL-17 production by PBMCs after stimulation with heat-killed Candida albicans.

Bars in each graphic represent mean values and standard errors. Statistical comparisons are indicated by the arrows; ns: non-significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Comparisons were done by the Mann-Whitney U test followed by correction for multiple comparisons.

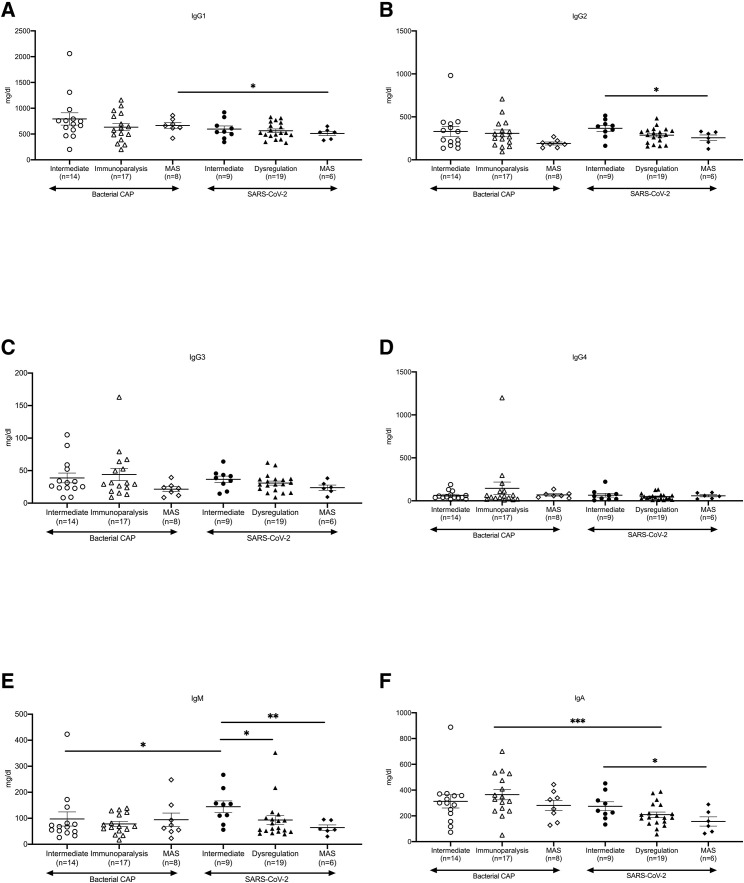

The next question was how this change of CD19+CD45+ lymphocytes is translated to serum immunoglobulins (Igs). Concentration of IgGs and their subclasses in the plasma of COVID-19 patients was low, as it was in bacterial CAP (Figures 3A–3D). However, IgM and IgA were higher than in bacterial CAP (Figures 3E and 3F). Overall, patients at MAS had lower IgG2, IgM, and IgA than those at an intermediate immune state, and patients at immune dysregulation had lower IgM than those at an intermediate immune state.

Figure 3.

Moderate Derangement of Circulating Immunoglobulins in Pneumonia Caused by SARS-CoV-2

Serum amounts of IgG subclasses (A–D), IgM (E), and IgA (F) of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 are shown. Patients are classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation, and MAS. Findings are compared with those in patients with bacterial CAP, who are classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, immunoparalysis, and MAS.

Bars in each graphic represent mean values and standard errors. Only statistically significant comparisons are indicated by the arrows; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.0001; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Comparisons were done by the Mann-Whitney U test followed by correction for multiple comparisons.

The IL-6 Blocker Tocilizumab Partially Rescues the Immune Dysregulation Driven by SARS-CoV-2

Sepsis-induced immunoparalysis is characterized by profound deficiency of monocytes for cytokine production upon ex vivo stimulation (Giamarellos-Bourboulis et al., 2011). Indeed, production of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by LPS-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with bacterial CAP classified for immunoparalysis was significantly lower than in patients at an intermediate state (Figure 4 A). That was not the case for patients with pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2, in whom PBMCs showed sustained TNF-α production after stimulation with LPS (Figure 4B). The function of PBMCs in patients with SRF caused by 2009H1N1 was also impaired, and there was lower TNF-α production, a pattern different from COVID-19 patients (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, stimulation of IL-1β was lower among patients with immune dysregulation than among patients with an intermediate immune state (Figures 4D–4F). IL-6, however, followed the stimulation pattern of TNF-α (Figures 4G–4I). This generated the hypothesis that in the case of SRF-aggravated pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2, there is a unique combination of defective antigen presentation and lymphopenia that leads to defective function of lymphoid cells, whereas monocytes remain potent for the production of TNF-α and IL-6.

Figure 4.

Main Features of Immune Dysregulation of Pneumonia Caused by SARS-CoV-2

(A) Production of TNF-α by PBMCs of patients with sepsis caused by bacterial CAP classified into intermediate state of immune activation and immunoparalysis.

(B) Production of TNF-α by PBMCs of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation, and MAS.

(C) Production of TNF-α by PBMCs of patients with SRF developing after infection caused by the 2009H1N1 virus and by SARS-CoV-2.

(D) Production of IL-1β by PBMCs of patients with sepsis caused by bacterial CAP classified into intermediate state of immune activation and immunoparalysis.

(E) Production of IL-1β by PBMCs of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified into three states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation, and MAS.

(F) Production of IL-1β by PBMCs of patients with SRF developing after infection caused by the 2009H1N1 virus and by SARS-CoV-2.

(G) Production of IL-6 by PBMCs of patients with sepsis caused by bacterial CAP classified into intermediate state of immune activation and immunoparalysis.

(H) Production of IL-6 by PBMCs of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified into states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation and MAS.

(I) Production of IL-6 by PBMCs of patients with SRF developing after infection caused by the 2009H1N1 virus and by SARS-CoV-2.

(J–L) Serum amounts of TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP of patients with CAP caused by SARS-CoV-2 classified into states of immune activation: intermediate, dysregulation and MAS.

Bars in each graphic represent mean values and standard errors. Statistical comparisons are indicated by the arrows; ns: non-significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001. Comparisons were done by the Mann-Whitney U test followed by correction for multiple comparisons.

As a next step, we measured circulating concentrations of TNF-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IL-6, and C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients infected by SARS-CoV-2. IFN-γ was below the limit of detection in all patients (data not shown), indicating that Th1 responses do not contribute to over-inflammation. No differences of circulating TNF-α concentrations were found between COVID-19 patients at the three states of immune classification (Figure 4J). In contrast, IL-6 and CRP concentrations were significantly higher among patients with immune dysregulation than among patients at an intermediate state of immune activation (Figures 4K and 4L). Given that IL-6 was below the limit of detection in some patients with immune dysregulation, we divided them into two groups as follows: seven patients with IL-6 below the limit of detection and 14 patients with detectable IL-6. Their severity was similar given that SOFA score and pneumonia severity indexes were similar (p values of comparisons were 0.937 and 0.877, respectively; data not shown).

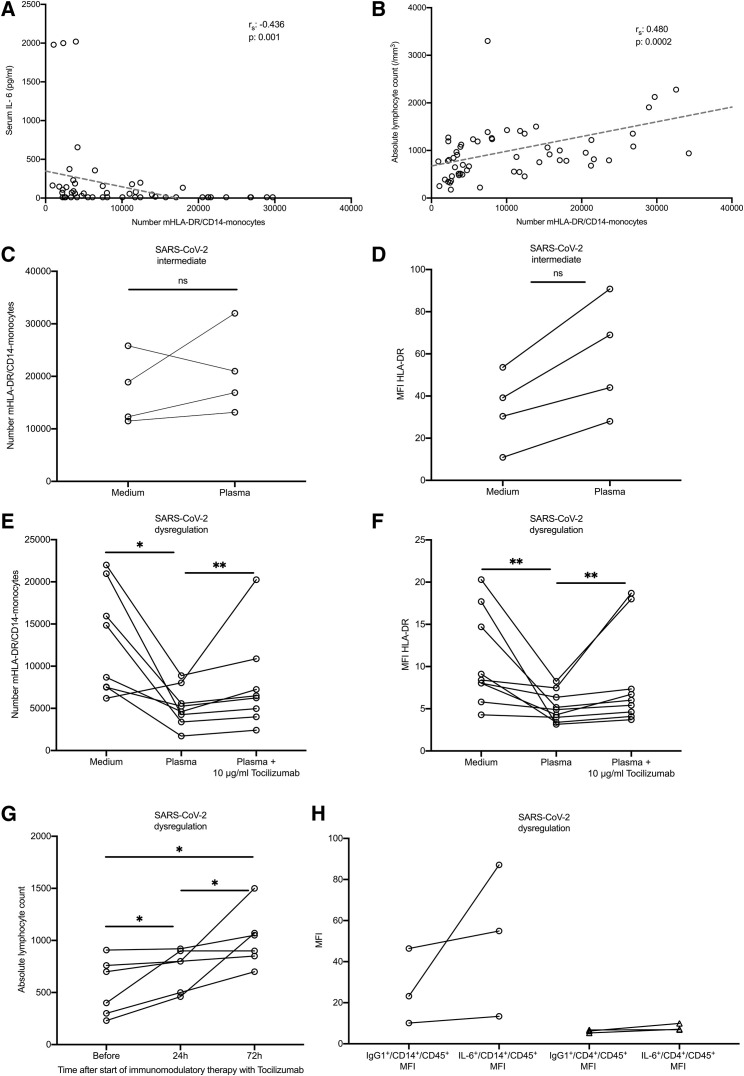

IL-6 is known to inhibit HLA-DR expression (Ohno et al., 2016), leading to the hypothesis that IL-6 over-production mediates the low HLA-DR expression on CD14 monocytes of COVID-19 patients. In agreement with this, negative correlation was found between serum amounts of IL-6 and the absolute number of HLA-DR molecules on CD14 monocytes of patients with COVID-19 but also between the absolute lymphocyte count and the absolute number of mHLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of patients with COVID-19 (Figures 5A and 5B). Furthermore, PBMCs from patients with immune dysregulation were cultured overnight in the presence of plasma of the COVID-19 patients, which was already shown to be rich in IL-6. The expression of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes was strongly inhibited by COVID-19 plasma from patients with immune dysregulation but not by plasma from patients with an intermediate immune state of activation (Figures 5C–5F); the addition of the specific blocker of the IL-6 pathway Tocilizumab partially restored the expression of HLA-DR on monocytes of all patients with immune dysregulation (Figures 5E and 5F). Treatment with Tocilizumab in six patients was accompanied by increase of the absolute lymphocyte blood count within the first 24 h (Figure 5G). IL-6 was produced partly by CD14 monocytes and partly by CD4 cells (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

Immune Dysregulation Caused by SARS-CoV-2 Is Mediated by IL-6

(A) Negative correlation between serum amounts of IL-6 and the absolute numbers of the mHLA-DR on CD14 monocytes. The Spearman’s (rs) co-efficient of correlation and the respective p value are provided.

(B) Correlation between the absolute lymphocyte count and the absolute numbers of mHLA-DR on CD14 monocytes. The rs co-efficient of correlation and the respective p value are provided.

(C) Changes of the absolute numbers of mHLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of four patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 with intermediate state of immune activation after incubation with medium and their plasma.

(D) Changes of the MFI of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of four patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 with intermediate state of immune activation after incubation with medium and their plasma.

(E) Changes of the absolute numbers of mHLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of eight patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 with immune dysregulation after incubation with medium and their plasma; modulation by the addition of the specific IL-6 blocker Tocilizumab is also shown.

(F) Changes of the MFI of HLA-DR on CD14 monocytes of eight patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 with immune dysregulation after incubation with medium and their plasma; modulation by the addition of the specific IL-6 blocker tocilizumab is also shown.

(G) Changes of the absolute lymphocyte count of six patients before and after start of treatment with Tocilizumab.

(H) Intracellular staining for IL-6 in CD14 monocytes and in CD4 lymphocytes of three patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 with immune dysregulation.

Statistical comparisons are indicated by the arrows; ns: non-significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01.

Discussion

All patients with pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 who develop SRF display hyper-inflammatory responses with features of either immune dysregulation or MAS, both of which are characterized by pro-inflammatory cytokines: the immune dysregulation described here, which is driven by IL-6 and not by IL-1β, and MAS, which is driven by IL-1β. There are two key features of this immune dysregulation: over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by monocytes and dysregulation of lymphocytes characterized by CD4 lymphopenia and subsequently B cell lymphopenia. In parallel, the absolute natural killer (NK) cell count is depleted, probably as result of the rapidly propagating virus.

It was previously shown that the addition of IL-6 in the growth medium of healthy dendritic cells attenuated HLA-DR membrane expression and decreased the production of IFN-γ by CD4 cells (Ohno et al., 2016). Three findings of our study are compatible with the proposal that IL-6 is one of the drivers of decreased HLA-DR on the CD14 monocytes: (1) IL-6 concentrations in the blood is inversely associated with HLA-DR expression (Figure 5A), (2) the addition of Tocilizumab in the plasma-enriched medium of cells partially restored the expression of HLA-DR on cell membranes (Figures 5E and 5F), and (3) absolute lymphocyte counts of six patients increased after Tocilizumab treatment (Figure 5G). Our findings are indirectly supported by the increase of circulating HLA-DR+ cells during convalescence of one case of COVID-19 of moderate severity (Thevarajan et al., 2020).

In conclusion, we identified a unique signature of immune dysregulation in the patients with SARS-CoV-2, characterized on the one hand by normal or high cytokine production capacity and increased circulating cytokines (especially IL-6) and on the other hand by defects in the lymphoid function associated with IL-6-mediated decrease in HLA-DR expression. These findings support the rationale of launched clinical trials on the efficacy of Anakinra, Sarilumab, Siltuximab, and Tocilizumab (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT04330638, NCT04317092, and NCT04315298 and EudraCT number 2020-001039-29) to elaborate anti-inflammatory responses in these patients.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| CD14-FITC (RMO52 clone) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#IM0645U; RRID: AB_130992 |

| CD45-PC5 (J33 clone) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#IM2653U; RRID: AB_10641226 |

| HLA-DR-RD1 (9-49 clone) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#6604366; RRID: AB_2832962 |

| IgG1-PE isotype control (679.1Mc7 clone) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A07796; RRID: AB_2832963 |

| IgG1-FITC isotype control (679.1Mc7 clone) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A07795; RRID: AB_2832964 |

| CD3-FITC/CD4-PE Antibody Cocktail (UCHT1/13b8.2 clones) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A07733; RRID: AB_2832965 |

| CD3-FITC/CD8-PE Antibody Cocktail | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A07734; RRID: AB_2832966 |

| CD3-FITC/CD(16+56)-PE Antibody Cocktail (UCHT1/3G8/N901 (NKH-1)) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#A07735; RRID: AB_1575965 |

| CD19-FITC/CD5-PE Antibody Cocktail | Beckman Coulter | Cat#IM1346U; RRID: AB_2832967 |

| Quantibrite Anti-HLA-DR/Anti-Monocyte (L243/MϕP9) | BD Biosciences | Cat#340827; RRID: AB_400137 |

| Mouse Anti-Human IL-6-PE (AS12 clone) | BD Biosciences | Cat#340527; RRID: AB_400442 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| VersaLyse Lysing Solution | Beckman Coulter | A09777 |

| Fixative Solution | Beckman Coulter | A07800 |

| eBioscience™ Brefeldin A Solution (1000x) | Invitrogen | 00-4506-51 |

| IntraPrep Permeabilization Reagent | Beckman Coulter | A07802 |

| RPMI 1640 W/ Stable Glutamine W/ 25 MM HEPES | Biowest | L0496 |

| Lymphosep, Lymphocyte Separation Media | Biowest | L0560 |

| PBS Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline w/o Magnesium, w/o Calcium | Biowest | L0615 |

| FBS Superior; standardized Fetal Bovine Serum, EU-approved | Biochrom | S0615 |

| Gentamycin Sulfate BioChemica | PanReac AppliChem | A1492 |

| Penicillin G Potassium Salt BioChemica | PanReac AppliChem | A1837 |

| Lipopolysaccharides from Escherichia coli O55:B5 | Sigma-Aldrich | L2880 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Human IL-1β uncoated ELISA | Invitrogen | 88-7261 |

| Human TNF-α uncoated ELISA | Invitrogen | 88-7346 |

| Human IL-6 ELISA | Invitrogen | 88-7066 |

| Human IL-17A (homodimer) uncoated ELISA | Invitrogen | 88-7176 |

| Human Ferritin ELISA | ORGENTEC Diagnostika GmbH | ORG 5FE |

| Human IFN-γ ELISA | Diaclone | 950.000.192 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | Graphpad Software | https://www.graphpad.com |

| SPSS | IBM | https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Evangelos J. Giamarellos-Bourboulis (egiamarel@med.uoa.gr).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

Data of this study are available after communication with the Lead Contact.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Blood was sampled from patients with CAP and sepsis and CAP by SARS-CoV-2 of either gender within the first 24 h of hospital admission (Table 1). CAP was defined as the presence of new infiltrate in chest X-ray in a patient without any contact with any healthcare facility the last 90 days; sepsis was defined by the Sepsis-3 criteria (Singer et al., 2016). COVID was diagnosed for patients with CAP confirmed by chest X-ray or chest computed tomography and positive molecular testing of respiratory secretions. For patients who required MV, blood sampling was performed within the first 24 h from MV and results were used for this analysis. Exclusion criteria were infection by the human immunodeficiency virus; neutropenia; and any previous intake of immunosuppressive medication (corticosteroids, anti-cytokine biologicals, and biological response modifiers). SRF was defined as severe decrease of the respiratory ratio necessitating intubation and mechanical ventilation. The studies were conducted under the 78/17 approval of the National Ethics Committee of Greece; the 23/12.08.2019 approval of the Ethics Committee of Sotiria Athens General Hospital; and the 26.02.2019 approval of the Ethics Committee of ATTIKON University General Hospital. Written informed consent was provided by patients or by first-degree relatives in case of patients unable to consent.

All data of patients with bacterial CAP screened for participation in the randomized clinical trial with the acronym PROVIDE (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03332225) were used. All patients admitted for CAP by SARS-CoV-2 from March 3 until March 30, 2020 participated in the study. No randomization to experimental groups was needed according to the study design.

Method Details

White blood cells were incubated for 15 min in the dark with the monoclonal antibodies anti-CD14 FITC, anti-HLA-DR-PE, anti-CD45 PC5 (Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France) and Quantibrite HLA-DR/anti-monocyte PerCP-Cy5 (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville Md). White blood cells were also incubated for 15 min with anti-CD3 FITC, anti-CD4 FITC and anti-CD19 FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate, emission 525 nm, Beckman Coulter); with anti-CD4 PE, anti-CD8 PE, and anti-CD(16+56) PE (phycoerythrin, emission 575nm, Beckman Coulter); and with anti-CD45 PC5 (emission 667 nm, Beckman Coulter). Fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter) were used for the determination of absolute counts. Cells were analyzed after running through the CYTOMICS FC500 flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Co, Miami, Florida). Isotypic IgG controls stained also with anti-CD45 were used for each patient. Results were expressed as absolute molecules of HLA-DR on CD14/CD14+CD45+ cells, percentages, and MFI.

In separate experiments, whole blood was treated with 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 60 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 followed by incubation in the dark for 15 min at room temperature with anti-CD4 FITC, anti-CD14 FITC (Beckman Coulter) and anti-CD45 PC5 followed by red blood cells lysis. Stained cells were then washed with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline and permeabilized with the IntraPrep Parmeabilization Reagent kit (Beckman Coulter). Anti-IL-6 PE (Beckman Coulter) was added and analyzed after flow cytometry.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated after gradient centrifugation over Ficoll (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) for 20 min at 1,400 g. After three washings in ice-cold PBS pH 7.2, PBMCs were counted in a Neubauer plate with trypan blue exclusion of dead cells. They were then diluted in RPMI 1640 enriched with 2mM of L-glutamine, 500 μg/mL of gentamicin, 100 U/mL of penicillin G, 10 mM of pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom) and suspended in wells of a 96-well plate. The final volume per well was 200 μL with a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL. PBMCs were exposed in duplicate for 24 h or 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 to different stimuli: 10 ng/mL of Escherichia coli O55:B5 lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma, St. Louis, USA); 5 × 105 colony forming units of heat-killed Candida albicans; 25% of patient plasma; or 10 μg/mL of Tocilizumab (Roche, Athens, Greece). After incubation, cells were removed and analyzed for flow cytometry. Concentrations of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A and IFNγ were measured in cell supernatants and/or serum in duplicate by an enzyme immunoassay (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). The lowest detections limits were as follows: for TNF-α, 40 pg/mL; for IL-1β, 10 pg/mL; for IL-6, 10 pg/mL; for IL-17A, 10 pg/mL; and for IFN-γ, 12.5 pg/mL. Concentrations of ferritin were measured in serum by an enzyme-immunoassay (ORGENTEC Diagnostika GmbH, Mainz, Germany); the lower limit of detection was 75 ng/mL.

Six patients with immune dysregulation were treated with single intravenous infusion of 8 mg/kg of Tocilizumab (RoAcremra, Roche) based on the National Health Care off-label provision for COVID-19. Absolute lymphocyte blood counts were compared before and after Tocilizumab infusion.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Qualitative data were presented as percentages and confidence intervals (CIs) and compared by the Fisher exact test. Qualitative data were presented as mean and standard deviation and compared by the Student’ s “t-test”; they were presented as mean and standard error and compared by the Mann-Whitney U test for small groups. Paired comparisons were done by the Wilcoxon’s rank-signed test. Non-parametric correlations were done according to Spearman. Any value of p below 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded in part by the Horizon 2020 grant ImmunoSep (847422) and in part by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis. M.G.N. is supported by an ERC Advanced Grant (833247) and a Spinoza grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Author Contributions

E.J.G.-B. conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version to be submitted. M.G.N. designed lab experiments, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version to be submitted. N.R., K.A., A.A., N.A., M.E.A., P.K., M.N., M.K., G.D., I.K., D.V., V.L., M.L., A.K., D.T., V.P., E.K., N.K., and A.K. collected blood samples, collected clinical information, reviewed the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version to be submitted. G.D., T.G., P.K., A.K., K.K., and G.R. performed lab experiments, reviewed the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version to be submitted. C.G. and A.K. contributed in data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and gave approval of the final version to be submitted.

Declaration of Interests

E.J.G.-B. has received honoraria from AbbVie USA, Abbott CH, InflaRx GmbH, MSD Greece, XBiotech Inc. and Angelini Italy; independent educational grants from AbbVie, Abbott, Astellas Pharma Europe, AxisShield, bioMérieux Inc, InflaRx GmbH, and XBiotech Inc; and funding from the FrameWork 7 program HemoSpec (granted to the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), the Horizon2020 Marie-Curie Project European Sepsis Academy (granted to the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), and the Horizon 2020 European Grant ImmunoSep (granted to the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis). A.A. has received honoraria and independent educational grants from Gilead, Pfizer, MSD, ViiV, Astellas, and Biotest.

Published: April 21, 2020

References

- Arabi Y.M., Murthy S., Webb S. COVID-19: a novel coronavirus and a novel challenge for critical care. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05955-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardet L., Galicier L., Lambotte O., Marzac C., Aumont C., Chahwan D., Coppo P., Hejblum G. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613–2620. doi: 10.1002/art.38690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Raftogiannis M., Antonopoulou A., Baziaka F., Koutoukas P., Savva A., Kanni T., Georgitsi M., Pistiki A., Tsaganos T., et al. Effect of the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus in the human immune system. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., van de Veerdonk F.L., Mouktaroudi M., Raftogiannis M., Antonopoulou A., Joosten L.A.B., Pickkers P., Savva A., Georgitsi M., van der Meer J.W., Netea M.G. Inhibition of caspase-1 activation in Gram-negative sepsis and experimental endotoxemia. Crit. Care. 2011;15:R27. doi: 10.1186/cc9974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D.S.C., et al. China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19 Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriazopoulou E., Leventogiannis K., Norrby-Teglund A., Dimopoulos G., Pantazi A., Orfanos S.E., Rovina N., Tsangaris I., Gkavogianni T., Botsa E., et al. Hellenic Sepsis Study Group Macrophage activation-like syndrome: an immunological entity associated with rapid progression to death in sepsis. BMC Med. 2017;15:172. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0930-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewicz A.C., Grienay M., Resche-Rigon M., Pirracchio R., Faivre V., Boval B., Payen D. Monocytic HLA-DR expression in intensive care patients: interest for prognosis and secondary infection prediction. Crit. Care Med. 2009;37:2746–2752. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ab858a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno Y., Kitamura H., Takahashi N., Ohtake J., Kaneumi S., Sumida K., Homma S., Kawamura H., Minagawa N., Shibasaki S., Taketomi A. IL-6 down-regulates HLA class II expression and IL-12 production of human dendritic cells to impair activation of antigen-specific CD4(+) T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2016;65:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1791-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C., Zhou L., Hu Z., Zhang S., Yang S., Tao Y., Xie C., Ma K., Shang K., Wang W., Tian D.S. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftogiannis M., Antonopoulou A., Baziaka F., Spyridaki A., Koutoukas P., Tsaganos T., Savva A., Pistiki A., Georgitsi M., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J. Indication for a role of regulatory T cells for the advent of influenza A (H1N1)-related pneumonia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010;161:576–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04208.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M., Deutschman C.S., Seymour C.W., Shankar-Hari M., Annane D., Bauer M., Bellomo R., Bernard G.R., Chiche J.D., Coopersmith C.M., et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315:801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevarajan I., Nguyen H.O., Koutsakos M., Druce J., Caly L., van de Sandt C.E., Jia X., Nicholson S., Catton M., Cowie B., et al. Breadth of concomitant immune responses prior to patient recovery: a case-report of non-severe COVID-10. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study are available after communication with the Lead Contact.