Highlights

-

•

qPCR for endemic species C HAdV types 1, 2, 5 and 6 were developed and validated.

-

•

qPCR assays permit sensitive, specific and quantitative identification of HAdVs.

-

•

The assays provide a rapid and convenient alternative to classical typing methods.

Abstract

Human adenoviruses (HAdVs) are medically important respiratory pathogens. Among the 7 recognized species (A–G), species C HAdVs (serotypes 1, 2, 5 and 6) are globally endemic and infect most people early in life. Species C HAdV infections are most often subclinical or mild and can lead to persistent shedding from the gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tracts. They can also cause severe disseminated disease in newborn and immunocompromised persons, where rapid and quantitative detection and identification of the virus would help guide therapeutic intervention. To this end, we developed quantitative type-specific real-time PCR (qPCR) assays for HAdV-1, -2, -5 and -6 targeting the HAdV hexon gene. All type-specific qPCR assays reproducibly detected as few as 5 copies/reaction of quantified hexon recombinant plasmids with a linear dynamic range of 8 log units (5–5 × 107 copies). No non-specific amplifications were observed with concentrated nucleic acid from other HAdV types or other common respiratory pathogens. Of 199 previously typed HAdV field isolates and positive clinical specimens, all were detected and correctly identified to type by the qPCR assays; 10 samples had 2 HAdV types and 1 sample had 3 types identified which were confirmed by amplicon sequencing. The species C HAdV qPCR assays permit rapid, sensitive, specific and quantitative detection and identification of four recognized endemic HAdVs. Together with our previously developed qPCR assays for the epidemic respiratory HAdVs, these assays provide a convenient alternative to classical typing methods.

1. Introduction

Human adenoviruses (HAdVs) cause a wide spectrum of diseases of the respiratory, ocular and gastrointestinal tracts. HAdVs are classified within the family Adenoviridae, genus Mastadenovirus, and are further divided into seven species (A–G) and over 50 recognized types (Harrach et al., 2012). Clinical symptoms, disease severity and epidemiological patterns of infection are often determined by virus species or type. Species C HAdVs (serotypes 1, 2, 5 and 6) are globally endemic and infect most people early in life (Schmitz et al., 1983). Approximately half of all HAdVs identified in a three year study of clinically severe infections among U.S. civilians were species C (Gray et al., 2007). Uniquely, species C viruses can establish infections of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues where they can persist without clinical evidence for life (Garnett et al., 2002). Infections of immunocompetent persons with these viruses are most often subclinical or lead to mild acute respiratory illnesses. However, immunosuppressed persons are at risk for severe disseminate life-threatening disease from primary infection or virus reactivation (Ison, 2006, Walls et al., 2003, Echavarría, 2008) as are immunologically naive newborns (Abzug and Levin, 1991, Cassir et al., 2014).

HAdVs were traditionally typed by neutralization and/or hemagglutination inhibition using type-specific hyperimmune animal antisera. A variety of molecular methods have since replaced immunotyping, including genome restriction analysis (Adrian et al., 1986), PCR-coupled microarrays (Lin et al., 2004); PCR-fragment length analysis (Adhikary et al., 2004, Ebner et al., 2006), electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Blyn et al., 2008), partial sequencing of specific target genes (Lu and Erdman, 2006, McCarthy et al., 2009) and more recently, full genome sequencing using next generation molecular methods (Torres et al., 2010). However, these methods are often complex and time consuming, and are not optimally designed for viral load determinations, important for monitoring HAdV disease progression and therapeutic efficacy. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) has been proposed as a rapid, sensitive and widely available technology for detection and identification of HAdVs more suited for the clinical diagnostic setting (Heim et al., 2003, Metzgar et al., 2010). We recently introduced type-specific qPCR assays for identification HAdVs most often associated with outbreaks of acute respiratory disease (species B types 3, 7, 11, 14, 16 and 21; species E type 4) to facilitate rapid public health response (Lu et al., 2013). In this study, we describe the development and validation of qPCR assays for the endemic species C HAdVs.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Virus strains and clinical specimens

HAdV prototype strains 1–51 and 179 geographically and temporally diverse respiratory specimens (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs, nasal wash, tracheal aspirate, blood, plasma and stool) and 20 field isolates collected during outbreak investigations and routine surveillance and previously determined positive for HAdV-1 (n = 63), -2 (n = 85), -5 (n = 43), and -6 (n = 8) by generic PCR and partial hexon gene sequencing (Lu and Erdman, 2006) were available from CDC archives for testing. To evaluate assay specificity, we also tested the assays against high concentrations of other potential respiratory pathogens, including respiratory syncytial virus (Long), human metapneumovirus (CAN 97-83), parainfluenza viruses 1–4, rhinovirus (1A), human coronaviruses (229E and OC43), influenza viruses A (A/California/09) and B (B/Shanghai/99), cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, human bocavirus (clinical specimen), Streptococcus pneumonia and Hemophilus influenza, and pooled nasal wash specimens predicted to contain diverse human microbiological flora from 20 consenting healthy new military recruits.

2.2. Primers and probes

Hexon gene sequences of HAdV prototype and field strains available from GenBank® (NCBI/NLM) were aligned and type-specific conserved regions were identified. Multiple primer/probe sets were designed using Primer Express™ software ver. 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to give predicted type-specific amplification and show no major non-specific homologies on BLAST analysis. Hydrolysis probes were labeled at the 5′-end with 6-carboxy-fluorescein (FAM) and at the 3′-end with Black Hole Quencher™ 1 (Biosearch Technologies, Inc., Novato, CA). Optimal primer/probe concentrations for each assay were determined by checkerboard titrations and primer/probe combinations giving the best overall performance with a limited panel of HAdVs were further evaluated. Primer/probe sets that performed best at conditions described below and with no identifiable cross-reactions were chosen for further study (Table 1 ). Primer and probe sequences used for detection of all HAdVs (pan-qPCR) were from Heim et al. (Heim et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Primer/probe sequences of HAdV qPCR assays.

| Assay | Primer/probesb | Sequence (5′-3′) | Hexon gene location | GenBank accession no. | Final concentration (nmol/L) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAdV-pana | Forward primer | GCCCCAGTGGTCTTACATGCACATC | 18881-18905 | AC_000017.1 | 500 | 132 |

| Reverse primer | GCCACGGTGGGGTTTCTAAACTT | 19012-18990 | 500 | |||

| Probe | TGCACCAGACCCGGGCTCAGGTACTCCGA | 18949-18921 | 100 | |||

| HAdV-1 | Forward primer | ATACCCAAACTGAAGGCAATCC | 19453-19474 | AC_000017.1 | 250 | 82 |

| Reverse primer | CATTCCACTGAGATTCTCCAACCT | 19534-19510 | 500 | |||

| Probe | TTTTTGCCGATCCCACTTATCAACCTGA | 19477-19504 | 100 | |||

| HAdV-2 | Forward primer | AAACGCTCGAGATCAGGCTACT | 19326-19347 | AC_000007.1 | 500 | 83 |

| Reverse primer | GCCCGCTTTTTGTAATTGTTTC | 19408-19387 | 500 | |||

| Probe | CACATGTCTATGCCCAGGCTCCTTTGTC | 19355-19382 | 50 | |||

| HAdV-5 | Forward primer | ACGATGACAACGAAGACGAAGTAG | 19290-19313 | AC_000008.1 | 250 | 70 |

| Reverse primer | GGCGCCTGCCCAAATAC | 19359-19343 | 500 | |||

| Probe | CGAGCAAGCTGAGCAGCAAAAAACTCA | 19315-19341 | 100 | |||

| HAdV-6 | Forward primer | CACTGTCCGGAATAAAAATAACTAAAGA | 19367-19394 | FJ349096.1 | 500 | 76 |

| Reverse primer | TTTGCCGGCACCTGCTA | 19443-19427 | 500 | |||

| Probe | ACAAATAGGAACTGCCGACGCCACA | 19401-19425 | 50 | |||

HAdV generic primer/probe sequences from Heim et al. (2003) (18).

Probes labeled at the 5′-end with the reporter molecule 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and at the 3′-end with Black Hole Quencher® 1 (Biosearch Technologies Inc., Novato, CA).

2.3. qPCR assays

Total nucleic acid (TNA) extracts were prepared from 100 μl of virus isolates or 200 μl of clinical specimens using the NucliSens® miniMAG or easyMAG extraction systems following the manufacturer's instructions (bioMérieux, Durham, NC). qPCR assays were run following conditions previously described (Lu et al., 2013). Briefly, 25 μl reaction mixtures were prepared by adding 5 μl of sample nucleic acid extract to 20 μl of iQ™ Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) containing optimal concentrations of primer/probes (Table 1). Thermocycling was performed on Stratagene Mx3000P qPCR system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) or an Applied Biosystems® 7500 Fast Dx Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) programed for: 3 min at 95 °C to activate the iTaq DNA polymerase and 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min at 55 °C. Positive test results were assigned to well-defined fluorescent curves that crossed the threshold within 45 cycles.

2.4. HAdV hexon recombinant plasmids (HRPs)

Recombinant DNA plasmids containing sequence-confirmed full hexon genes of HAdV-1 (Ad.71), 2 (Ad.6), 5 (Ad.75) and 6 (Ton.99) prototype strains were constructed by commercial sources (DNA Technologies Inc., Gaithersburg, MD; Cellomics Technology, Baltimore, MD) for use as positive controls and for analytical sensitivity studies. The HRPs were quantified using the Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit with the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Standard curves for quantitative assessment were prepared from replicate serial 10-fold dilutions (1–1 × 107 copies/μl) of the HRPs in 10 mM TE buffer containing 100 μg/ml herring sperm DNA (Promega, Madison, WI).

3. Results

3.1. Analytical sensitivity of qPCR assays

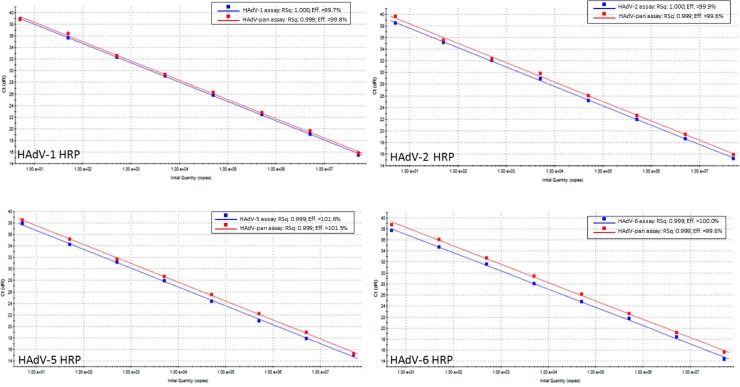

The optimized qPCR assays were first evaluated with serial dilutions of the quantified HRPs to estimate their limits of detection (LODs). Serial dilutions of the respective HRPs containing 50, 5 and 0.5 copies/reaction were each tested in 16 replicates. The type-specific and pan-qPCR assays gave linear dynamic ranges of 8 log units (5–5 × 107 copies) and amplification efficiencies exceeding 99% (Fig. 1 ). All type-specific qPCR assays could reproducibly detect 5 HRP copies/reaction (Table 2 ). The HAdV pan-qPCR assay showed comparable LODs with type-specific qPCR assays.

Fig. 1.

Plots of serial 10-fold dilutions of the respective hexon recombinant plasmids ranging from 5 to 5 × 107 copies/reaction obtained with HAdV type-specific- (blue) and pan- (red) qPCR assays. Plot inserts show calculated linear correlation coefficients (R2) and amplification efficiencies for each assay.

Table 2.

HAdV qPCR assays limits of detection.

| HRP copies/reaction | No. HAdV qPCR assay positives with 16 replicates of hexon recombinant plasmids (HRPs)a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAdV-1 HRP |

HAdV-2 HRP |

HAdV-5 HRP |

HAdV-6 HRP |

|||||

| HAdV-1 | HAdV-pan | HAdV-2 | HAdV-pan | HAdV-5 | HAdV-pan | HAdV-6 | HAdV-pan | |

| 0.5 | 5/16 | 4/16 | 7/16 | 3/16 | 5/16 | 7/16 | 9/16 | 6/16 |

| 5 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 |

| 50 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 | 16/16 |

Underlines designate assay limits of detection with >70% replicate positives.

3.2. Analytical specificity of qPCR assays

The primer/probes of each qPCR assay were evaluated in silico with HAdV hexon gene sequences published on GenBank; no significant sequence homologies were observed with other HAdV types that would predict cross-reactivity. BLAST analyses found no significant homologies with human genome or other human microbial flora that would possibly lead to false positive results. Each qPCR assay was then tested against concentrated genomic DNA (CT values <20 by HAdV pan-qPCR) from HAdV prototype strains 1–51 to assess type-specificity. No cross-reactions were detected (Table 3 ). The specificity of the qPCR panel was further assessed by testing laboratory cultures or positive clinical specimens known to contain high concentrations of viral and bacterial pathogens that may be present in the respiratory tract as described in the Materials and Methods. No positive results were obtained with any of the samples with the exception of the human nasal wash pool, where weak positive results (CT, 38.9 and 38.4) were obtained with the HAdV-pan and HAdV-1 assays, respectively. Subsequent PCR and partial hexon gene sequencing confirmed low level HAdV-1 in the pool, indicating that the virus was present in the upper respiratory tract of one or more of the individuals sampled.

Table 3.

HAdV qPCR assays specificity.

| Samples | HAdV qPCR assaysa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAdV-pan | HAdV-1 | HAdV-2 | HAdV-5 | HAdV-6 | |

| HAdV-1 | 14.9 | 14 | – | – | – |

| HAdV-2 | 15.2 | – | 14.4 | – | – |

| HAdV-5 | 15.0 | – | 15.0 | – | |

| HAdV-6 | 15.6 | – | – | – | 15.3 |

| HAdV-3, -4, -7 to -51 | 12.7–19.5 | – | – | – | – |

| Other respiratory pathogensb | – | – | – | – | – |

| Pooled human nasal washc | 39.0c | 38.4c | – | – | – |

CT values shown for positive samples.

See Materials and Methods.

HAdV-1 confirmed by PCR and sequencing of partial hexon gene (15).

3.3. Clinical evaluation of HAdV qPCR assays

To assess the performance of the qPCR assays with diverse HAdV field isolates and positive clinical specimens, TNA from 199 previously typed HAdV strains were tested by all assays (Table 4 ). HAdV was detected in all samples and correctly identified to type by the respective qPCR assay. However, 2 different HAdV types were found in 10 clinical specimens [HAdV-1 (CT, 30.1)/-2 (CT, 31.8); HAdV-1 (CT, 29.0)/-5 (CT, 36.4); HAdV-2 (CT, 32.5)/-1 (CT, 40.4); HAdV-2 (CT, 34.0)/-5 (CT, 39.9); HAdV-2 (CT, 32.5)/-5 (CT, 38.3); HAdV-2 (CT, 35.2)/-5 (CT, 37.1); HAdV-5 (CT, 25.6)/-1 (CT, 32.9); HAdV-5 (CT, 35.3)/-1 (CT, 37.2); HAdV-5 (CT, 31.0)/-1 (CT, 38.0); HAdV-5 (CT, 19.2)/-1 (CT, 37.9)] and 3 HAdV types were found in one specimen [HAdV-2 (CT, 37.6)/-1 (CT, 40.0)/-5(CT, 40.2)]. All qPCR findings were confirmed by sequencing the respective qPCR amplicons. In most cases, only the predominant type (type with the lower CT value) was identified by our routine method of generic PCR and partial hexon gene sequencing (Lu and Erdman, 2005).

Table 4.

HAdV qPCR assays results with 199 HAdV field isolates and positive clinical specimens.

| Virusa | N | HAdV qPCR assay results |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAdV-pan |

HAdV-1 |

HAdV-2 |

HAdV-5 |

HAdV-6 |

|||||||

| + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | ||

| HAdV-1 | 63 | 63 | 0 | 63 | 0 | 1b | 62 | 1b | 62 | 0 | 63 |

| HAdV-2 | 85 | 85 | 0 | 2b | 83 | 85 | 0 | 4b | 81 | 0 | 85 |

| HAdV-5 | 43 | 43 | 0 | 4b | 39 | 0 | 43 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 43 |

| HAdV-6 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

HAdV type determined by PCR and sequencing of hexon hypervariable regions 1–6 (15).

qPCR amplicons sequence-confirmed for co-presence of HAdV-1, -2 or -5 DNA in the respective samples.

4. Discussion

In a previous study we described development of type-specific qPCR assays for the epidemic respiratory HAdVs types (Lu et al., 2013). In this study, we expanded this assay panel to include type-specific qPCR assays for the endemic species C viruses. Species C HAdVs can cause severe disseminate life-threatening disease in immunecompromised patients, particularly in the transplant recipients. Rapid and quantitative detection and identification of the endemic species C HAdVs among newborn and transplant recipients with severe disseminated diseases would help guide therapeutic intervention. Four species C HAdVs assays proved sensitive and specific and allowed quantitative assessment of viral loads based on standard curve analysis using quantified HPRs.

Real-time PCR technology for type-specific identification of HAdVs was first employed by Jones et al. (Jones et al., 2011) to detect and identify HAdVs-1, -2, -5 and -6 using the Joint Biological Agent Identification and Diagnostic System (BioFire Diagnostics, Salt Lake City, Utah) and LightCycler® 2.0 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) platforms. However, their assays were not only predicted to be 10–20 times less sensitive than our corresponding qPCR assays, but also showed some non-specific cross-reactions among the four virus types. Furthermore, their assays were developed and validated on platforms that are not in common use outside of U.S. Department of Defense-affiliated laboratories.

Among the clinical specimens evaluated in our study, 11 were found to contain multiple species C HAdV types. In contrast, our routine typing method of generic PCR and Sanger sequencing of a partial region of the hexon gene was only able to identify the predominant HAdV type in most cases. Kores et al. (Kroes et al., 2007) has shown the sequential emergence of multiple HAdVs after pediatric stem cell transplantation making simultaneous detection of HAdVs coinfections especially challenging. Our type-specific qPCR assays will prove useful for type identification and management of mixed HAdV infections in immunocompromised persons and may facilitate future studies to better define the full complexity of HAdV infections in this population.

Despite these advantages, our qPCR assays have some limitations. Although our expanded assay panel covers HAdV types most frequently associated with disseminated disease in immunosuppressed persons, species A (HAdV-31) and species B (HAdV-34 and -35) viruses that may also cause severe infections in these population would not be identified (Echavarría, 2008, Madisch et al., 2006). Furthermore, since our qPCR assays target short sequences in the HAdV hexon gene, novel or hexon/fiber recombinant viruses would not be recognized. For example, a rare recombinant species C HAdV designated type 57 that was recently reported to contain a unique hexon gene and a HAdV-6 fiber gene (Walsh et al., 2011) would not have been identified by our assays.

In conclusion, our qPCR assays permit sensitive, specific and quantitative detection and identification of the four species C HAdVs and allow differentiation of HAdV coinfections which are difficult to distinguish by other methods. Together with our previously developed qPCR assays for the epidemic respiratory HAdVs, these assays provide a rapid and convenient alternative to classical typing methods.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Acknowledgement

Partial data from this manuscript was presented at the 30th Annual Clinical Virology Symposium, Daytona Beach, FL, April 27–30, 2014.

References

- Abzug M.J., Levin M.J. Neonatal adenovirus infection: four patients and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 1991;87:890–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikary A.K., Inada T., Banik U., Numaga J., Okabe N. Identification of subgenus C adenoviruses by fiber-based multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:670–673. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.670-673.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian T., Wadell G., Hierholzer J.C., Wigand R. DNA restriction analysis of adenovirus prototypes 1–41. Arch. Virol. 1986;91:277–290. doi: 10.1007/BF01314287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blyn L.B., Hall T.A., Libby B., Ranken R., Sampath R., Rudnick K., Moradi E., Desai A., Metzgar D., Russell K.L., Freed N.E., Balansay M., Broderick M.P., Osuna M.A., Hofstadler S.A., Ecker D.J. Rapid detection and molecular serotyping of adenovirus by use of PCR followed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:644–651. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00801-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassir N., Hraiech S., Nougairede A., Zandotti C., Fournier P.E., Papazian L. Outbreak of adenovirus type 1 severe pneumonia in a French intensive care unit, September–October 2012. Euro Surveill. 2014;19(39) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.39.20914. (Pii 20914) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner K., Rauch M., Preuner S., Lion T. Typing of human adenoviruses in specimens from immunosuppressed patients by PCR-fragment length analysis and real-time quantitative PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:2808–2815. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00048-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echavarría M. Adenoviruses in immunocompromised hosts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008;21:704–715. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00052-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett C.T., Erdman D., Xu W., Gooding L.R. Prevalence and quantitation of species C adenovirus DNA in human mucosal lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2002;76:10608–10616. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10608-10616.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray G.C., McCarthy T., Lebeck M.G., Schnurr D.P., Russell K.L., Kajon A.E., Landry M.L., Leland D.S., Storch G.A., Ginocchio C.C., Robinson C.C., Demmler G.J., Saubolle M.A., Kehl S.C., Selvarangan R., Miller M.B., Chappell J.D., Zerr D.M., Kiska D.L., Halstead D.C., Capuano A.W., Setterquist S.F., Chorazy M.L., Dawson J.D., Erdman D.D. Genotype prevalence and risk factors for severe clinical adenovirus infection: United States 2004–2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:1120–1131. doi: 10.1086/522188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrach, B., Benkő, M., Both, G.W., Brown, M., Davison, A.J., Echavarría, M., Hess, M., Jones, M.S., Kajon, A., Lehmkuhl, H.D., Mautner, V., Mittal, S.K., Wadell, G., 2012. Family Adenoviridae., p. 125–141, In: King, AMQ, Adams, M.J., Carstens, E.B., Lefkowitz, E.J. (Eds.), Virus Taxonomy: Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, San Diego, CA.

- Heim A., Ebnet C., Harste G., Pring-Akerblom P. Rapid and quantitative detection of human adenovirus DNA by real-time PCR. J. Med. Virol. 2003;70:228–239. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ison M.G. Adenovirus infections in transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43:331–339. doi: 10.1086/505498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M.S., Hudson N.R., Gibbins C., Fischer S.L. Evaluation of type-specific real-time PCR assays using the LightCycler and J.B.A.I.D.S. for detection of adenoviruses in species HAdV-C. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes A.C., de Klerk E.P., Lankester A.C., Malipaard C., de Brouwer C.S., Claas E.C., Jol-van der Zijde E.C., van Tol M.J. Sequential emergence of multiple adenovirus serotypes after pediatric stem cell transplantation. J. Clin. Virol. 2007;38:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B., Vora G.J., Thach D., Walter E., Metzgar D., Tibbetts C., Stenger D.A. Use of oligonucleotide microarrays for rapid detection and serotyping of acute respiratory disease-associated adenoviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:3232–3239. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3232-3239.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Erdman D.D. Molecular typing of human adenoviruses by PCR and sequencing of a partial region of the hexon gene. Arch. Virol. 2006;151:1587–1602. doi: 10.1007/s00705-005-0722-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Trujillo-Lopez E., Lott L., Erdman D.D. Quantitative real-time PCR assay panel for detection and type-specific identification of epidemic respiratory human adenoviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:1089–1093. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03297-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisch I., Wölfel R., Harste G., Pommer H., Heim A. Molecular identification of adenovirus sequences: a rapid scheme for early typing of human adenoviruses in diagnostic samples of immunocompetent and immunodeficient patients. Med. Virol. 2006;78:1210–1217. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy T., Lebeck M.G., Capuano A.W., Schnurr D.P., Gray G.C. Molecular typing of clinical adenovirus specimens by an algorithm which permits detection of adenovirus coinfections and intermediate adenovirus strains. J. Clin. Virol. 2009;46:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzgar D., Gibbins C., Hudson N.R., Jones M.S. Evaluation of multiplex type-specific real-time PCR assays using the LightCycler and joint biological agent identification and diagnostic system platforms for detection and quantitation of adult human respiratory adenoviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:1397–1403. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01600-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz H., Wigand R., Heinrich W. Worldwide epidemiology of human adenovirus infections. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1983;117:455–466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S., Chodosh J., Seto D., Jones M.S. The revolution in viral genomics as exemplified by the bioinformatic analysis of human adenoviruses. Viruses. 2010;2:1367–1381. doi: 10.3390/v2071367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls T., Shankar A.G., Shingadia D. Adenovirus: an increasingly important pathogen in paediatric bone marrow transplant patients. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003;3:79–86. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh M.P., Seto J., Liu E.B., Dehghan S., Hudson N.R., Lukashev A.N., Ivanova O., Chodosh J., Dyer D.W., Jones M.S., Seto D. Computational analysis of two species C human adenoviruses provides evidence of a novel virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:3482–3490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00156-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]