Abstract

In a new working memory paradigm, CapMan, we independently investigated brain activity associated with capacity and manipulation of information. The investigation of Capacity, resulted in activation of the fronto-parietal network of regions that overlapped with areas usually found to be active in working memory tasks. The investigation of Manipulation revealed a more dorsal network of areas that also overlapped with areas usually found to be active in working memory tasks, but that did not overlap with the areas associated with Capacity. The CapMan paradigm thus appears to be able to separate the processes associated with capacity and manipulation increases and promises to be a valuable addition to the tools available for the study of working memory.

Keywords: fMRI, fronto-parietal network, working memory, capacity, manipulation

Working memory (WM) refers to a set of cognitive processes that allow information to be maintained and/or manipulated for short periods of time (Narayanan et al., 2005), and has been shown to rely on a distributed network of brain regions (D'Esposito et al., 2000; Wager & Smith, 2003a). However, there is currently no single paradigm that allows these WM subprocesses to be independently investigated. While much has been learned about WM subprocesses using the numerous extant paradigms, it is difficult to investigate the interaction of these subprocesses unless the components of WM can be independently manipulated within a single paradigm. Here, we introduce such a paradigm.

Information manipulation has been studied with paradigms such as the task switching paradigm (Wylie et al., 2004; 2006), the PASAT (Christodoulou et al., 2001) and the N-Back task (Cohen et al., 1997; Callicott et al., 1999; Owen et al., 1999; Jansma et al., 2000; Veltman et al., 2003a; Owen et al., 2005; Muller & Knight, 2006) among others. While these tasks examination of the brain activity associated with information manipulation, they also require other executive processes, such as encoding, maintenance, and retrieval that might also affect brain activity (Narayanan et al., 2005, Veltman, Rombouts, Dolan, 2003). For example, in addition to requiring information manipulation, the N-Back task entails capacity demands. Hence, the brain regions activated during the N-Back task might not be functionally linked to a particular WM subprocess but reflect an interaction of processes required for task performance (Veltman et al., 2003b). For this reason, we developed a domain-general task (verbal and spatial domains) that allows independent assessment of brain regions associated with capacity and manipulation demands: CapMan.

We expected to see activation of the fronto-parietal network of regions in association with the CapMan paradigm, based on a large body of previous WM-related work. Specifically, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) are often reported to be engaged during information manipulation and when one has to hold information ‘on-line’ (Wager & Smith, 2003; Owen et al., 2005). Even though these regions might not have one specific role since they have also been implicated in other executive processes (Owen et al., 2005; Jansma et al., 2007; Cools & D'Esposito, 2011; O'Doherty, 2011), they are consistently reported to be engaged in WM processing. Another region that has been implicated in WM is the posterior parietal cortex (PPC). The pattern of activity of this region is similar to the PFC regions mentioned above, with neurophysiological and neuroimaging studies reporting increased neuronal firing and blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) activity in PPC during WM tasks that involve maintenance and manipulation of information (Champod & Petrides, 2007; Rawley & Constantinidis, 2009; Champod & Petrides, 2010). Below, we show that components of WM could be separated within a single WM task, the CapMan. Most importantly, the CapMan paradigm allows examining regions sensitive to the interaction of the WM processes.

Seventeen (mean age ± SD = 30.12 ± 11.66) neurologically normal right-handed participants (7 female) whose primary language was English were recruited for the current study. All had normal color vision with normal or corrected-to-normal acuity. Subjects had no prior history of drug abuse or any neurological conditions. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Kessler Foundation Research Center. All participants provided informed consent and were paid for participation.

A 3-Tesla Siemens Allegra scanner was used to acquire all fMRI data. Behavioral data acquisition, randomization and stimulus presentation was administered using the “E-Prime” software (Schneider et al, 2002). The paradigm was presented in the scanner in a blocked design. A T2-weighted pulse sequence was used to collect functional images in 32 contiguous slices during four runs, and there were 185 acquisitions per run (echo time = 30 ms; repetition time = 2000 ms; field of view = 22 cm; flip angle = 80°; slice thickness = 4 mm, matrix = 64×64, in-plane resolution = 3.438 mm2). A high-resolution magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) image was also acquired (TE= 4.38 ms; TR=2000 ms, FOV = 220 mm; flip angle = 8°; slice thickness = 1 mm, NEX=1, matrix=256 × 256, in-plane resolution=0.859 × 0.859 mm), and was used to normalize the functional data into standard space.

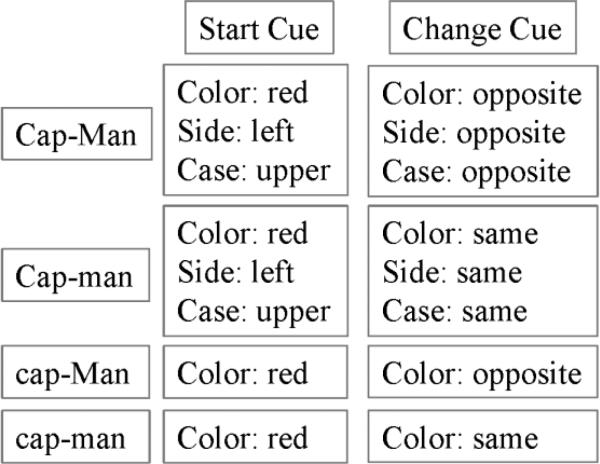

All participants completed a series of practice trials before scanning. Two factors (capacity and manipulation) had two difficulty levels (high vs. low), creating a 2 × 2 design. During the CapMan practice, participants completed one block of each of the four conditions (high capacity and manipulation: CAP-MAN, high capacity, low manipulation: CAP-man, low capacity, high manipulation: cap-MAN, low capacity and manipulation: cap-man) (Figure 1a). They were asked to respond as quickly as possible without sacrificing accuracy. Participants were able to repeat the practice of the relevant task block if it was evident that they did not understand the instructions.

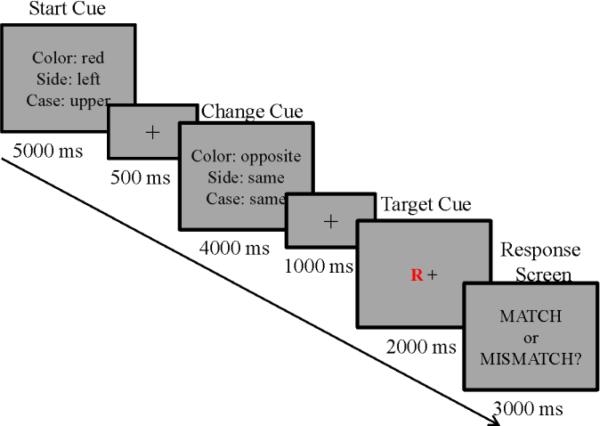

Figure 1.

A. Matrix of CapMan conditions depicting information presented during the Start and Change cues. There was 90% probability of cue change during the high manipulation condition, and 10% probability of a cue changing during the low manipulation condition. B. A graphical example of the high capacity, low manipulation condition (Cap-man). The Start cue indicates that a match would consist of a red, upper-case target letter, to the left side of the fixation. The Change cue indicates that the side and case features remain unaltered. The stimulus shown would be mismatch, since the letter appears in red and not in blue as directed by the change cue. There was 90% probability of cue change during the high manipulation condition, and 10% probability of a cue changing during the low manipulation condition (for each feature).

Each trial of the CapMan consisted of three stages: a start cue, a change cue and a target stimulus (Figure 1b). The Start cue informed subjects about the feature of the target stimulus they had to attend to and served the purpose of loading the WM capacity. To engage both verbal and spatial domains of the WM, the start cue parameters were drawn from 6 possible features that had 2 possible values, i.e., ‘color’ (red vs. blue),‘case’ (upper vs. lower case), ‘side’ (left vs. right side of fixation point), ‘motion’ (a field of dots in the background drifting either up or down), 'sound' (vowel vs. consonant) and ‘typeface’ (plain vs. italic). The start cue was presented for 5000ms, followed by an inter-stimulus interval (ISI; 500ms). During low and high capacity blocks participants had to maintain either one or three features in WM (low vs. high information load, respectively). That is, during a low capacity trial, the start cue screen displayed only one feature to be remembered (e.g., ‘side’), while during a high capacity trial, the start cue screen presented participants with three features to be remembered (e.g., ‘color, side, case’).

The change cue, presented for 4000ms followed by an ISI (1000ms), instructed subjects whether to look for the same or opposite value of each cued feature and served the purpose of taxing manipulation demands of WM. Based on the information provided by the change cue participants were required to either maintain the same feature value presented during the start cue (low manipulation) or to change the value to its opposite (high manipulation). That is, during the low information manipulation trial, the change cue screen required switching only one of the features from the start cue; during a high information manipulation trial, the change cue screen required switching three features from the start cue. In addition, we fixed the probability of feature change to 90% during the high manipulation condition in order to ensure that subjects did not simply encode the opposite feature of the start cue. In the low manipulation trials, each feature had a 10% probability of changing (and was therefore 90% likely to remain unchanged).

The target stimulus was presented after the change cue and stayed on the screen for 2000ms, followed immediately by a response screen (3000ms) and the inter-trial interval (500ms). Subjects’ had to decide whether or not the features in the target stimulus matched change cue features. If the target stimulus matched the features updated by the change cue, subjects were instructed to indicate a match. If the target stimulus did not match the features updated by the Change cue, subjects were instructed to indicate a mismatch.

Each CapMan condition was run in a separate block in the scanner. There were four blocks of 64 seconds followed by 22 seconds of rest. Each task block was composed of four trials resulting in 16 total trials, each lasting 16 seconds. The order of the blocks was counterbalanced across subjects. Error rate and response time (RT) data was analyzed with a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Planned contrasts were also performed as part of the ANOVA. We observed a significant main effect of capacity on RT (F(1,14) = 18.23, p=0.001), with subjects taking longer to respond in the high capacity condition than in the low capacity condition. No main effect of manipulation on RT was observed, F(1,14) = 2.14, p=0.17 (Supplementary Table 1).

For each of four fMRI runs, the first 5 images were discarded to ensure steady state magnetization. All images were preprocessed using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) (Cox, 1996). The realignment, co-registration and normalization were done in a single transform. This was accomplished by calculating and saving the parameters necessary for realignment (i.e., the spatial co-registration of all images in each time-series to the first image of the series). Next, the parameters necessary to co-register the first image in each time-series with the high resolution MPRAGE were calculated and saved. Third, the MPRAGE image (1×1×1 mm voxels) was warped into standard space, and the warping parameters were saved. Finally, the transforms necessary to realign, co-register and warp the data into standard space were combined and applied to the functional time-series data in a single transformation. The images were then smoothed, using an 8 mm3 Gaussian smoothing kernel, and scaled to the mean intensity. The data were then deconvolved, using a boxcar function in which each condition was represented by a regressor. Motion parameters and 3 polynomial regressors (to model signal drift) were included as regressors of no interest.

Group-level statistics were performed using ANOVAs. All group-level statistical maps were thresholded using both the alpha level and cluster size correction (extent of activation). The alpha level was set at p<0.01 and the cluster size was set at 19 contiguous voxels in native space. The results of Monte Carlo simulations showed that this combination resulted in a corrected alpha level of p<0.05.

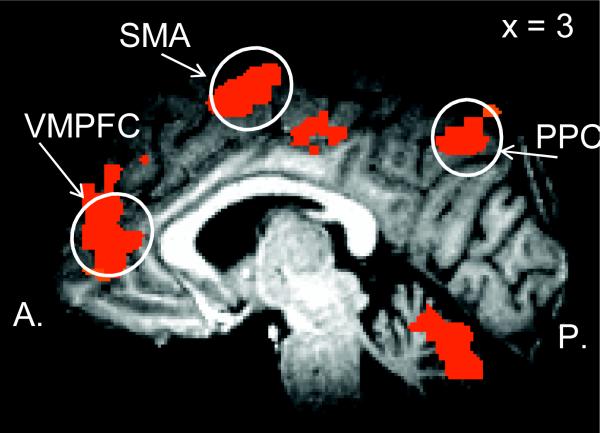

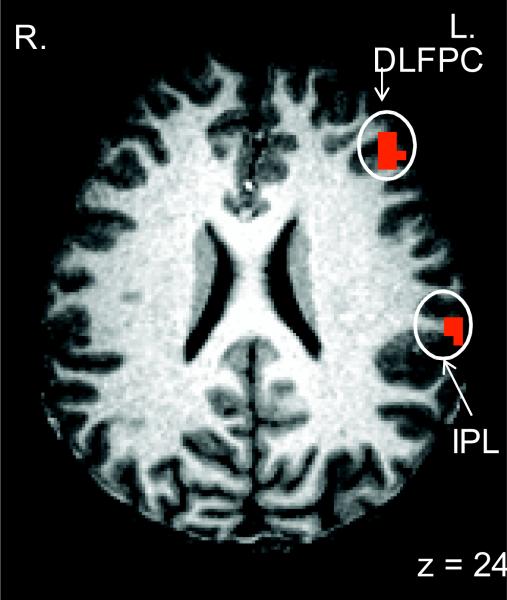

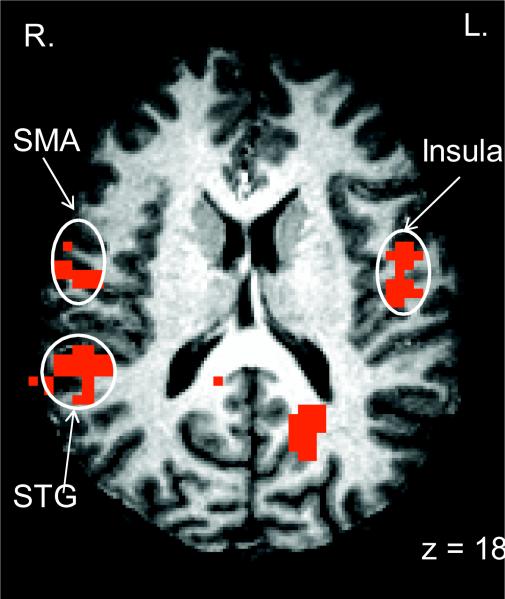

We performed a whole-brain voxel-wise ANOVA with Capacity (high vs. low) and Manipulation (high vs. low) as within-subject factors. The CapMan paradigm activated the fronto-parietal network of regions (DLPFC, VMPFC, PPC) that have been previously shown to be associated with specific WM subprocesses (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the CapMan paradigm appears to be able to isolate brain networks associated with both capacity and manipulation and allows independent study of these processes. Indeed, the main effect of Capacity revealed a network of regions that included superior parietal regions (BAs 7 and 40), dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal regions (BA 9 and 46), and VMPFC (BA 10). Meanwhile, the DLPFC (BA 46), PPC (BA 40) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; BA 31) and the precentral gyrus (BA 6) exhibited increased activity in association with increased manipulation requirements. There were no regions that showed a decrease in activation in association with increased manipulation demands.

One of the particular strengths of the CapMan paradigm is that it allows investigating both capacity and manipulation within a single paradigm, i.e. not only the main effect of capacity and manipulation, but also their interaction. When we analyzed the interaction of capacity and manipulation, we observed activation of the fronto-parietal WM network of regions that has been shown to be active in a wide variety of cognitive tasks that involve attention and executive control such as the N-Back task. However, it is difficult to interpret the functional role these regions play during WM task performance since capacity and manipulation cannot be independently manipulated (Narayanan et al., 2005). In the CapMan task, the interaction between capacity and manipulation revealed three areas of reliable activation: PCC (BA 31), lingual gyrus and superior temporal gyrus (BA 22). In order to explore this interaction further, the individual voxel probability threshold was relaxed to p<0.05 and the voxelwise cluster threshold was increased to 94 to correct for multiple comparisons. When this was done, a larger network of areas exhibited a Capacity × Manipulation interaction (Figure 1c). In all cases, the interaction resulted from high levels of activation when both capacity and manipulation demands were high and relatively low levels of activation when capacity and/or manipulation were low. This network included bilateral precentral gyrus (BA 6; supplementary motor area), left inferior frontal gyrus (BA 44), PPC (BAs 7 and 40), and PCC (BA 31) (Supplementary Table 2).

The fronto-parietal network activated by the CapMan task appears to be organized in a dorso-ventral fashion, such that the more dorsal areas are associated with processing Capacity (i.e. frontal and superior parietal areas) while more ventral areas are associated with Manipulation (i.e. the insula and inferior parietal areas). This pattern broadly agrees with the findings of a meta-analysis of functional imaging studies on WM (Wager & Smith, 2003b). In that meta-analysis, a broad cross-section of WM literature was subjected to quantitative analyses, and the same dorsal-ventral distinction was found.

The manipulation condition of the CapMan task resulted in more localized activity than the capacity condition. Specifically, compared to the capacity condition that resulted in widespread PFC activation, during the manipulation condition PFC activity was restricted to the DLPFC, a region that was shown to be engaged during WM manipulation (Wager & Smith, 2003).

Lesion studies suggest that the DLPFC is necessary for information manipulation during WM (Barbey, Koenigs and Grafman, 2012), while neuroimaging studies show that, as processing of information becomes more efficient, the BOLD response in the DLPFC and other PFC regions decreases in healthy individuals but not in individuals with TBI who continue to activate their PFC (Koch et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2012). Therefore, we would expect to see a more robust activation of this region as manipulation demands are increased during the CapMan paradigm, or when the task is presented to clinical populations such as patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) with attentional and WM problems.

In the current study, we were specifically interested in identifying and detecting brain activity associated with capacity and manipulation demands of our WM task. Specifically, we wanted to detect BOLD activity associated with capacity and manipulation conditions of the CapMan task. For that reason we used a blocked design instead of the event-related design, which is more suitable for detecting differences in hemodynamic response function associated with the condition of interest (Poldrack et al., 2011).

Our study demonstrates the value of independent investigation of capacity and manipulation of information in WM. The CapMan paradigm allowed us to distinguish areas associated with these two critical subprocesses of WM in a novel way. Additionally, the CapMan paradigm revealed brain areas that showed an interaction of Capacity and Manipulation. Future studies should examine brain activity associated with not only capacity and manipulation, but also brain regions associated with the length of time that information must be maintained in WM. This would extend the current paradigm from CapMan to CapManDu (standing for CAPacity, MANipulation and DUration). In addition, testing this paradigm with a clinical population that has WM impairments, such as individuals with traumatic brain injury (Kasahara et al., 2011), might shed light on the brain regions that are not only sufficient but necessary for WM CAPacity, MANipulation and DUration.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

A. Activity in the VMPFC and the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) associated with the main effect of capacity demandsB. The DLPFC and the insula activity associated with a main effect of manipulation during the CapMan task. C. Brain activity associated with the interaction of Capacity and Manipulation during the CapMan task. DLPFC = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VMPFC = ventromedial prefrontal cortex; STG = superior temporal gyrus; PPC = posterior parietal cortex.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the Kessler Foundation Research Center and from the National Institutes of Health (1R42NS050007-02to Dr. Randall Barbour).

References

- Barbey AK, Koenigs M, Grafman J. Dorsolateral Prefrontal Contributions to Human Working Memory. Cortex. 2013;49:1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callicott JH, Mattay VS, Bertolino A, Finn K, Coppola R, Frank JA, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Physiological characteristics of capacity constraints in working memory as revealed by functional MRI. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:20–26. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champod AS, Petrides M. Dissociable roles of the posterior parietal and the prefrontal cortex in manipulation and monitoring processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:14837–14842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607101104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champod AS, Petrides M. Dissociation within the frontoparietal network in verbal working memory: a parametric functional magnetic resonance imaging study. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:3849–3856. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0097-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou C, DeLuca J, Ricker JH, Madigan NK, Bly BM, Lange G, Kalnin AJ, Liu WC, Steffener J, Diamond BJ, Ni AC. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of working memory impairment after traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:161–168. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JD, Perlstein WM, Braver TS, Nystrom LE, Noll DC, Jonides J, Smith EE. Temporal dynamics of brain activation during a working memory task. Nature. 1997;386:604–608. doi: 10.1038/386604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, D'Esposito M. Inverted-U shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and biomedical research, an international journal. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M, Postle BR, Rypma R. Prefrontal cortical contributions to working memory: evidence from event-related fMRI studies. Experimental Brain Research. 2000;133:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s002210000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansma JM, Ramsey NF, Coppola R, Kahn RS. Specific versus nonspecific brain activity in a parametric N-back task. NeuroImage. 2000;12:688–697. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansma JM, Ramsey NF, de Zwart JA, van Gelderen P, Duyn JH. fMRI study of effort and information processing in a working memory task. Human brain mapping. 2007;28:431–440. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K, Wagner G, von Consbruch K, Nenadic I, Schultz C, Ehle C, Reichenbach J, Sauer H, Schlosser R. Temporal changes in neural activation during practice of information retrieval from short-term memory: an fMRI study. Brain research. 2006;1107:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BC, Saykin AJ, McAllister TW. Functional MRI of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI): progress and perspectives from the first decade of studies. Brain imaging and behavior. 2012;6:193–207. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9173-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller NG, Knight RT. The functional neuroanatomy of working memory: contributions of human brain lesion studies. Neuroscience. 2006;139:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Doherty J. Contributions of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to goal- directed action selection. In: Schoenbaum G, Gottfried JA, Murray EA, Ramus SJ, editors. Blackwell Science Publ. Oxford: 2011. pp. 118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, Herrod NJ, Menon DK, Clark JC, Downey SP, Carpenter TA, Minhas PS, Turkheimer FE, Williams EJ, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ, Petrides M, Pickard JD. Redefining the functional organization of working memory processes within human lateral prefrontal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:567–574. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, McMillan KM, Laird AR, Bullmore E. N-back working memory paradigm: a meta-analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Human brain mapping. 2005;25:46–59. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawley JB, Constantinidis C. Neural correlates of learning and working memory in the primate posterior parietal cortex. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2009;91:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman DJ, Rombouts SA, Dolan RJ. Maintenance versus manipulation in verbal working memory revisited: an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2003a;18:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltman DJ, Rombouts SARB, Dolan RJ. Maintenance versus manipulation in verbal working memory revisited: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2003b;18:247–256. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging Studies of Working Memory: A Meta-Analysis. Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2003a;3:255–274. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Smith EE. Neuroimaging studies of working memory: a meta-analysis. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2003b;3:255–274. doi: 10.3758/cabn.3.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie GR, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. Don't think of a white bear: an fMRI investigation of the effects of sequential instructional sets on cortical activity in a task-switching paradigm. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;21:279–297. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie GR, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. Jumping the gun: is effective preparation contingent upon anticipatory activation in task-relevant neural circuitry? Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:394–404. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.