Abstract

Aims

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4, a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in various cell types, serves as a co-stimulator molecule to influence immune response. This study aimed to investigate associations between DPP-4 inhibitors and risk of autoimmune disorders in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Taiwan.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used the nationwide data from the diabetes subsection of Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. Cox proportional hazards models were developed to compare the risk of autoimmune disorders and the subgroup analyses between the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups.

Results

A total of 774,198 type 2 diabetic patients were identified. The adjusted HR of the incidence for composite autoimmune disorders in DPP-4i group was 0.56 (95% CI 0.53–0.60; P < 0.001). The subgroup analysis demonstrated that the younger patients (aged 20–40 years: HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.35–0.61; aged 41–60 years: HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.46–0.55; aged 61–80 years: HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.58–0.68, P = 0.0004) and the lesser duration of diabetes diagnosed (0–5 years: HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.44–0.52; 6–10 years: HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.43–0.53; ≧ 10 years: HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.96, P < 0.0001), the more significant the inverse association of DPP-4 inhibitors with the incidence of composite autoimmune diseases.

Conclusions

DPP-4 inhibitors are associated with lower risk of autoimmune disorders in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Taiwan, especially for the younger patients and the lesser duration of diabetes diagnosed. The significant difference was found between the four types of DPP-4 inhibitors and the risk of autoimmune diseases. This study provides clinicians with useful information regarding the use of DPP-4 inhibitors for treating diabetic patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00592-020-01533-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: DPP-4 inhibitors, Rheumatoid arthritis, Autoimmune disease, Diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Sitagliptin was the first dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP-4i) marketed in Taiwan. It was introduced in 2009 followed by vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin. DPP-4i has blood glucose-lowering effects by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). They are second-line oral anti-hyperglycemic drugs listed by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) just after metformin [1, 2]. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), also known as CD26, a transmembrane type II glycoprotein belonging to the prolyl oligopeptidase family, is expressed in various cell types, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, macrophages and T lymphocytes [3]. Since DPP-4 has wide distribution, it is involved in a great number of physiological processes. Evidence has shown that DPP-4 plays a role in chemotaxis, signal transduction, T cell-mediated immune responses and lymphokine synthesis [4–6]. Hence, apart from its role in glucose homeostasis, CD26/DPP-4 expression may be associated with various pathogenic conditions such as autoimmune disease [7], inflammatory disease and malignancies [8].

Several groups have investigated altered DPP-4 activity in autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [4, 9–13], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [14], psoriasis [15], inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [16] and multiple sclerosis [17]. Many studies discovered decreased expression of both CD26 and levels of DPP-4 activity in subjects with RA, a systemic inflammatory disease involving joint destruction. Animal models demonstrated increased severity of RA resulting from lower DPP-4 activity in the synovial fluid of CD26 knockout mice [18, 19]. Several case reports demonstrated cases of DPP-4 inhibitor-induced synovitis [20], RA or polyarthritis [21–23]. In addition, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also warned in 2015 that DPP-4i treatment for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) may cause severe joint pain. Until now, while DPP-4 has several biological functions in proinflammatory pathways [24, 25], the exact pathological pathways and influence of DPP-4 on the immune system, particularly autoimmune disorders, are not well known. Little has been studied about the relationships between DPP-4 inhibitors, RA and other autoimmune disorders and the possible mechanism behind these relationships.

Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that DPP-4 inhibitors, one of the incretin-based oral anti-diabetic agents, plays a fundamental role in immune homeostasis in T2DM patients. We conducted a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study and the subgroup analyses about the risk factors influencing the occurrence of the composite autoimmune diseases by DPP4 inhibitors to explore the associations between DPP-4i and risk of systemic autoimmune disorders in patients with T2DM in Taiwan and to compare the outcomes between the four different types of DPP-4i.

Methods

Study cohort

Taiwan’s National Health Insurance (NHI) system is a universal compulsory program launched by Taiwanese Government in March 1995 which covers over 96% of Taiwan’s population [26, 27]. Every Taiwanese person who is registered in the census for over 6 months is required to join the NHI system. When individuals are included in the NHI program, they can attend outpatient visits, the emergency room and admission services. Extensive computerized administrative data sets derived from this program have been maintained by the National Health Research Institute (NHRI) of Taiwan and are made available to investigators for research purposes after de-identifying individual health information.

The protocol of this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study was approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (201700350B0). We extracted data from the diabetes subsection of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) in Taiwan between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. Because Sitagliptin was the first marketed DPP-4i in Taiwan, which was started to extensively wide prescribed since 2009, we choose the time frame from 2009 to 2013 for cumulative analysis of occurrences of autoimmune diseases. We recruited patients age ≥ 20 years with ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for T2DM (ICD-9-CM: 250.XX) [28, 29]. We further divided participants into a DPP-4i group and a control (DPP-4i-naïve) group. The DPP-4i group was defined as patients receiving any prescription of DPP-4i during the cohort period. DPP-4i drugs of interest included four types: sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin. The index date of the DPP-4i group was defined as the earliest date of DPP-4i prescription. The index date of the DPP-4i-naïve group is the date randomly assigned by duration from the day of DM diagnosis to the DPP-4i prescription date of the DPP-4i group. Conducting this matching of prescription time-distribution allowed us to avoid the imbalance of prescription times between the two groups, which can lead to survival bias. The exclusion criteria were as follows: type 1 DM, age younger than 20 years or older than 80 years, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or malignancy diagnosed before enrollment, and those who had used incretin-based drugs before the index date (Supplementary Figure). The participants aged older than 80 years were considered the immunocompromised population; hence, they were excluded to reduce the possibility to alter the outcomes. The study cohort was followed continuously until December 31, 2013.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes were the occurrence of composite autoimmune disease, including RA, SLE, inflammatory bowel disease, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis and ankylosing spondylitis (AS), which were defined as at least two visits with a disease-specific diagnosis code ([International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for RA: 714.0, 714.30, 714.31, 714.32, 714.33; SLE: 710.0; inflammatory bowel disease: 255.xx or 256.xx; Sjögren syndrome: 710.2; psoriasis: 696.0, 696.1, 696.5, 696.8 and AS: 720.0] and among which the RA, SLE, inflammatory bowel disease and Sjögren syndrome were confirmed with a catastrophic illness certificate (CIC). The catastrophic illnesses were classified by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan. After diagnosing a patient with RA, SLE, inflammatory bowel disease or Sjögren syndrome, a specialist can submit the CIC application on the patient’s behalf. The NHI administration will assign another senior rheumatologist to anonymously review the application according to the criteria for the specific autoimmune disorders. In addition, we also identified the infection-associated diagnosis by using ICD-9-CM codes such as 995.9X, 001.XX, 139.XX.

A subgroup analysis for the primary AD composite outcomes was conducted on different categories of 15 pre-specified subgroup variables, including age, sex, comorbidities such as hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia, coronary arterial disease (CAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic renal disease (CRD) and liver disease, T2DM duration and medications such as metformin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, thiazolidinedione, alpha-glucosidase and insulin. The inconsistency of effect of DPP-4i on the outcome across different categories of subgroup variables was assessed using the interaction term of subgroup variable by study group (DPP-4i vs. control).

Covariates

Data of variables related to autoimmune disorders recorded for the 365-day period before the index data were collected, including age and sex; comorbidities (i.e., HTN, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, COPD, chronic kidney disease (CKD) and liver cirrhosis); and medications, including lipid-lowering drugs and systemic steroids. The comorbidities mentioned above were recorded twice as an outpatient diagnosis or once as a diagnosis on admission within 1 year before the index date using the ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes (i.e., ICD-9-CM codes for hypertension: 401*, 402*, 403*, 404*, 405*; dyslipidemia: 272*; ischemic heart disease: 410*, 411*, 412*, 413*, 414*; COPD: 491*, 492*, 496*; CKD:403*, 404*, 580*-589*, 016.0, 095.4, 236.9, 250.4, 274.1, 442.1, 440.1, 446.21, 447.3, 572.4, 642.1, 646.2, 753.1, 283.11; liver cirrhosis: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6). Diabetes severity was characterized by the duration of diabetes and the number of anti-diabetic drugs taken.

Statistical analysis

To control for potential confounders when comparing baseline characteristics between the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups, propensity score (PS) matching was performed using 1:1 prescription time-distribution PS-matched analysis. Baseline characteristics between DPP-4i and prescription time-distribution-matched DPP-4i-naïve groups were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression. Incidence rates and hazard ratios (HR) of the composite autoimmune diseases were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the Cox model. Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted for the cumulative incidence of the outcomes in both groups. In addition, the adjusted HRs for the outcomes in dependence of different types of DPP-4i were also analyzed. We performed Cox regression analysis after adjustment for the possible confounders, including to evaluate the difference of HRs for the outcomes between four types of DPP-4i. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS EG software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of DPP4i versus DPP4i-naïve groups after PS matching

From January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2013, a total of 2,163,659 subjects from the NHIRD with diagnosis of T2DM were identified. After applying the exclusion criteria, 1,959,039 patients with T2DM were eligible for analysis. Finally, after applying the 1:1 PS matching method, 387,099 patients were included in both the matched DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups. The baseline characteristics of the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups were well balanced after PS matching. The mean age of the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups was around 60.2 versus 60.1 years, respectively. The age groups of 20–40 years were 4.9% versus 5.1%, 41–60 years were 42.8% versus 43%, and 61–80 years were 52.4% versus 51.9% in the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups, respectively. Males made up 52.1% of the DPP-4i group and 53.3% of DPP-4i-naïve group. The mean T2DM treatment duration was 7.4 years in the DPP-4i group and 7.3 years in the DPP-4i-naïve group. T2DM duration was below 5 years in 38.8% of participants in the DPP-4i group versus 39.7% in the DPP-4i-naïve group; T2DM duration was between 6 and 10 years in 27.1% of participants in the DPP-4i group versus 28.3% in the DPP-4i-naïve group, and was more than 11 years in 34.1% versus 32% of participants in the DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups, respectively. Dyslipidemia and hypertension were the two most prevalent comorbidities, followed by ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and liver cirrhosis in both DPP-4i and DPP-4i-naïve groups. Among the dyslipidemia patients (77.4%), 26% were receiving statins. Regarding the co-administration of other types of anti-diabetic drugs, 65.5% of the DPP-4i group and 66.8% of the DPP-4i-naïve group received metformin; 62.6% and 63.6% received sulfonylurea; 5.3% and 5.3% received meglitinides; 12.5% and 11.6% received thiazolidinediones; 10.5% and 9.9% received alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, respectively. The percentage of insulin usage was about 8% in both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and underlying medical conditions in DDP-4i and DPP-4i-naive groups

| Characteristics | DDP-4i (n = 387,099) | DPP-4i-naive group (n = 387,099) | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.2 ± 11.3 | 60.1 ± 11.6 | 0.002 |

| Age group | |||

| 20–40 years | 18,883 (4.9) | 19,815 (5.1) | − 0.011 |

| 41–60 years | 165,578 (42.8) | 166,494 (43.0) | − 0.005 |

| 60–80 years | 202,638 (52.4) | 200,790 (51.9) | 0.010 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 201,809 (52.1) | 206,149 (53.3) | − 0.022 |

| Female | 185,290 (47.9) | 180,950 (46.8) | 0.022 |

| DM duration, years | 7.4 ± 4.3 | 7.3 ± 4.2 | 0.033 |

| DM duration groups | |||

| 0–5 years | 150,186 (38.8) | 153,689 (39.7) | − 0.019 |

| 6–10 years | 104,866 (27.1) | 109,602 (28.3) | − 0.027 |

| ≥ 11 years | 132,047 (34.1) | 123,808 (32.0) | 0.045 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 299,692 (77.4) | 299,044 (77.3) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 293,326 (75.8) | 292,038 (75.4) | 0.008 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 141,958 (36.7) | 139,321 (36.0) | 0.014 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 78,768 (20.4) | 77,494 (20.0) | 0.008 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 87,256 (22.5) | 85,229 (22.0) | 0.013 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 12,379 (3.2) | 12,285 (3.2) | 0.001 |

| Medications | |||

| Anti-diabetic drugs | |||

| Metformin | 253,464 (65.5) | 258,563 (66.8) | − 0.028 |

| Sulfonylurea | 242,467 (62.6) | 246,215 (63.6) | − 0.020 |

| Meglitinides | 20,594 (5.3) | 20,322 (5.3) | 0.003 |

| Thiazolidinediones | 48,435 (12.5) | 44,817 (11.6) | 0.029 |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors | 40,664 (10.5) | 38,432 (9.9) | 0.019 |

| Insulin | 30,721 (7.9) | 31,244 (8.1) | − 0.005 |

| Steroid | 4515 (1.2) | 4587 (1.2) | − 0.002 |

| Statin | 101,516 (26.2) | 100,885 (26.1) | 0.004 |

DDP-4i dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, SMD standardized mean difference, DM diabetes mellitus, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide 1

Outcomes during follow-up in DPP-4i versus DPP-4i-naïve groups

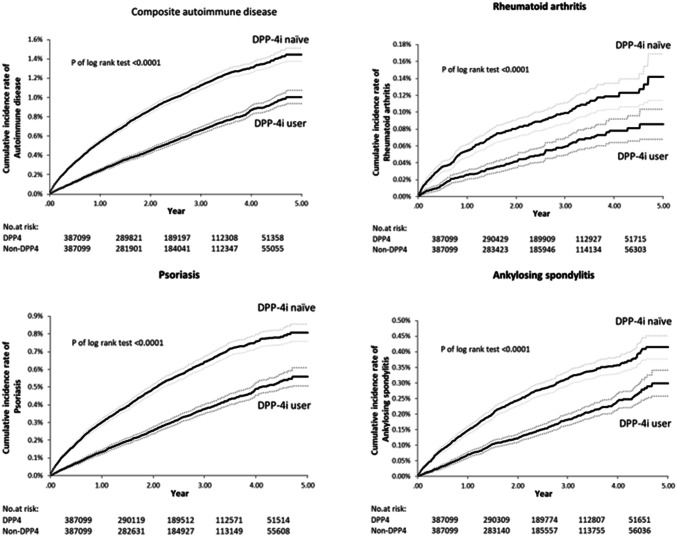

During the follow-up periods, the cumulative incidence curves of autoimmune disease in DPP-4 inhibitor group showed significant reduction as compared with DPP-4 inhibitor-naïve group (Fig. 1 ). In Table 2, the overall occurrence of composite autoimmune diseases was less in the DPP-4i group than in the DPP-4i-naïve group (1833 [4.7‰] vs. 3196 [8.3‰], respectively). HR of the composite autoimmune diseases was 0.56 with 95%CI 0.53–0.60, P < 0.0001. Rheumatoid arthritis occurred in 170 patients (0.4‰) in the DPP-4i group and 300 (0.8‰) patients in the DPP-4i-naïve group (HR: 0.56; 95% CI, 0.46–0.68; P < 0.001). Psoriasis occurred in 1034 (2.7‰) patients in the DPP-4i group and 1809 (4.7‰) patients in the DPP-4i-naïve group (HR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.52–0.61; P < 0.001). Ankylosing spondylitis occurred more in the DPP-4i-naïve group (n = 893, 2.3‰) than in the DPP-4i group (n = 512, 1.3‰) (HR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.50–0.63; P < 0.0001). Systemic lupus erythematosus occurred in 28 patients (0.01‰) in the DPP-4i group and 50 (0.01‰) patients in the DPP-4i-naïve group (HR: 0.55; 95% CI, 0.35–0.88; P = 0.012). Inflammatory bowel diseases occurred in 2 patients (0.00‰) in the DPP-4i group and 3 (0.00‰) patients in the DPP-4i-naïve group (HR: 0.66; 95% CI, 0.11–3.95; P = 0.648). Sjögren syndrome occurred in 101 patients (0.03‰) in the DPP-4i group and 172 (0.04‰) patients in the DPP-4i-naïve group (HR: 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46–0.75; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). The above HRs reported in Table 2 were all adjusted for the possible confounding factors, including age, gender, T2DM diagnosis duration and multi-comorbidities (i.e., hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease and liver cirrhosis); and medications (i.e., anti-diabetic medicine, lipid-lowering drugs and systemic steroids) for the composite endpoints.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of cumulative incidence curves of autoimmune diseases between DPP-4 inhibitor group and DPP-4 inhibitor-naïve group

Table 2.

Outcomes of occurrence of autoimmune diseases during the follow-up periods

| Outcome | DDP4i (n = 387,099) | DPP4i-naive group (n = 387,099) | DDP4i versus DPP4i-naive group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Composite autoimmune disease, ‰ | 1833 (0.47) | 3196 (0.83) | 0.56 (0.53–0.60) | < 0.001* |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 170 (0.04) | 300 (0.08) | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) | < 0.001* |

| Psoriasis | 1034 (0.27) | 1809 (0.47) | 0.56 (0.52–0.61) | < 0.001* |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 512 (0.13) | 893 (0.23) | 0.56 (0.50–0.63) | < 0.001* |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 28 (0.01) | 50 (0.01) | 0.55 (0.35–0.88) | 0.012* |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | 2 (0.00) | 3 (0.00) | 0.66 (0.11–3.95) | 0.648 |

| Sjögren syndrome | 101 (0.03) | 172 (0.04) | 0.58 (0.46–0.75) | < 0.001* |

The Cox regression model was adjusted for age, gender, type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis duration, comorbidities including dyslipidemia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and medications such as oral anti-diabetic agents, insulin, steroids and statin

DDP4i dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

*indicates a significance in statistical analysis

Comparisons of the occurrence of infection rate between DPP4i and non-DPP4i

We further analyzed the adjusted HR for the occurrence of infection rate in type 2 diabetic patients taking DPP-4i compared with those without taking DPP-4i. The results demonstrated a decreased infection rate in DPP-4i group compared with non-DPP-4i group (aHR: 0.45, 95%CI: 0.44–0.46, P < 0.001) after adjustment for the possible confounders, including age, gender, type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis duration, comorbidities including dyslipidemia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and medications such as oral anti-diabetic agents, insulin, steroids and statin.

Subgroup analysis of occurrence of composite autoimmune diseases between DPP4i versus comparison (non-DPP4i)

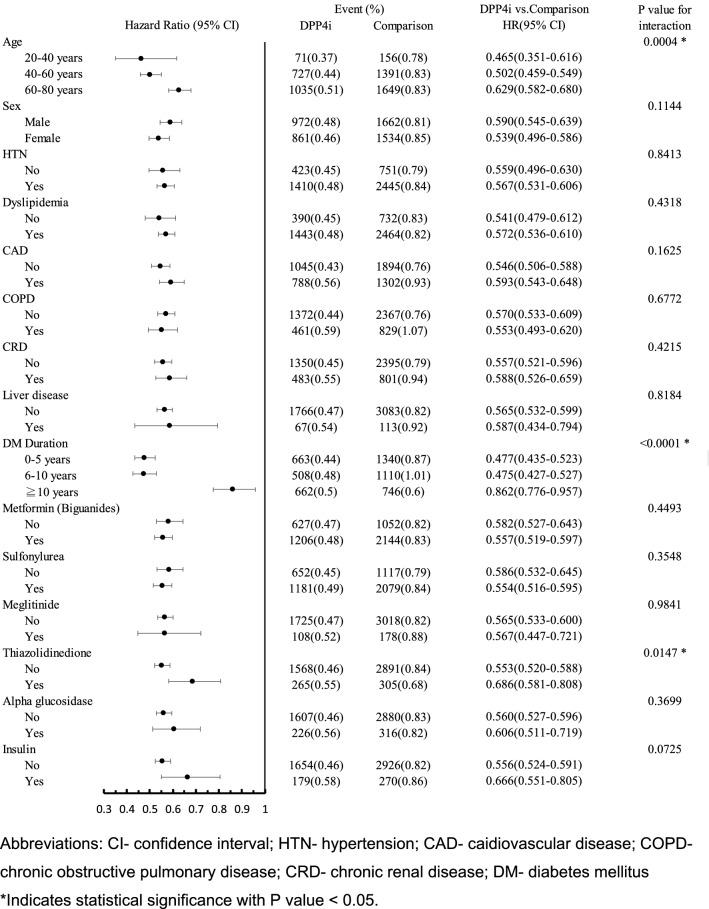

Subgroup analysis of occurrence of composite autoimmune diseases was performed according to the following pre-specified subgroups: age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal disease, liver disease, T2DM duration, with or without add-on anti-hyperglycemic drugs, such as metformin, sulfonylurea, meglitinide, thiazolidinedione, alpha-glucosidase and insulin. We found that the younger patients (aged 20–40 years: HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.35–0.61; aged 41–60 years: HR 0.50, 95% CI 0.46–0.55; aged 61–80 years: HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.58–0.68, respectively, P = 0.0004) and the lesser duration of diabetes diagnosed (T2DM duration 0–5 years: HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.44–0.52; 6–10 years: HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.43–0.53; ≧ 10 years: HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.78–0.96, respectively, P < 0.0001), the more significant reduction of the incidence of composite autoimmune diseases in DPP-4 inhibitors group (Fig. 2). The similar results of the reduced incidence of composite autoimmune diseases in DPP-4 inhibitors group were also found after resubgrouping of diabetes duration (0–10 years vs. over 10 years) and age (20–60 years vs. > 60 years) (Suppl Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Subgroup analysis of occurrence of composite autoimmune diseases between DPP4i versus DDP4i-naïve groups

Furthermore, patient without history of using thiazolidinediones has more prominent reduction of the incidence of composite autoimmune diseases in DPP-4 inhibitors group (HR 0.55, 95% CI 0.52–0.59 vs. HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.58–0.81, P = 0.015) (Fig. 2).

Comparisons of outcomes between different types of DPP-4i drugs

We further compared the cumulative incidence of autoimmune diseases between the four types of DPP-4 inhibitors, including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin. The results demonstrated that the incident composite autoimmune disease and AS were significantly different between each of the four DPP-4i drugs by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparisons of differences of occurrence in several autoimmune diseases outcomes between the four types of DPP-4 inhibitors (P = 0.048 and P = 0.006, respectively). The Cox regression analysis after adjustment for the possible confounders revealed that saxagliptin group reduced the incidence of composite AD by 22% (adjusted HR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.62–0.98) and AS by 46% (adjusted HR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.37–0.79) as compared with sitagliptin group, whereas linagliptin group reduced the incidence of RA by 75% (adjusted HR: 0.25, 95% CI: 0.11–0.59) as compared with sitagliptin group. The Cox regression model was adjusted for age, gender, T2DM diagnosis duration, comorbidities including dyslipidemia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and medications such as oral anti-diabetic agents, insulin, steroids and statin (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of outcomes of autoimmune diseases between the different types of DPP-4i

| Outcome | Sitagliptin (n = 294,175) | Vildagliptin (n = 45,715) | Saxagliptin (n = 35,423) | Linagliptin (n = 11,786) | Adjusted HR (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vild versus Sita | Saxa versus Sita | Lina versus Sita | |||||

| Composite AD, ‰ | 647 (2.20) | 78 (1.71) | 83 (2.34) | 17 (1.44) | 1.04 (0.82–1.32) | 0.78 (0.62–0.98)* | 0.87 (0.54–1.42) |

| RA | 65 (0.22) | 9 (0.20) | 9 (0.25) | 6 (0.51) | 0.91 (0.45–1.83) | 0.72 (0.36–1.45) | 0.25 (0.11–0.59)* |

| Psoriasis | 357 (1.21) | 49 (1.07357) | 41 (1.16) | 6 (0.51) | 0.92 (0.68–1.24) | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 1.38 (0.61–3.09) |

| AS | 177 (0.60) | 18 (0.40) | 32 (0.90) | 2 (0.17) | 1.22 (0.75–1.99) | 0.54 (0.37–0.79)* | 1.96 (0.49–7.91) |

The Cox regression analysis was adjusted for age, gender, type 2 diabetes mellitus diagnosis duration, comorbidities including dyslipidemia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and medications such as oral anti-diabetic agents, insulin, steroids, statin

AD autoimmune disease, RA rheumatoid arthritis, AS ankylosing spondylitis, CI confidence interval, Sita sitagliptin, Vild vildagliptin, Saxa saxagliptin, Lina linagliptin

*indicates a significance in statistical analysis

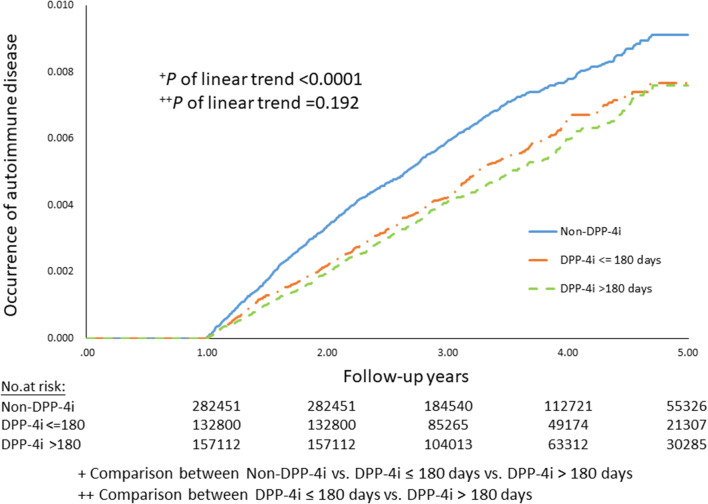

Dose-dependent analysis of DPP-4i in occurrence of autoimmune disease in type 2 diabetic patients

Furthermore, we analyzed the dose-dependent effects of DPP-4i in occurrence of autoimmune disease during the 5-year follow-up period (2009–2013) in T2DM patients recorded in the NHIRD. It appeared that there was no statistical significance in difference between DPP-4i ≤ 180 days versus DPP-4i > 180 days (P = 0.192). Nevertheless, the reduced risk of occurrence of AD occurred in DPP-4i users compared with non-DPP-4i users in T2DM patients in spite of the treatment duration (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Dose-dependent analysis of DPP-4i in occurrence of autoimmune disease in type 2 diabetic patients

Discussion

The present study is a large population-based retrospective cohort study to analyze associations between DPP-4 inhibitors, including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin and linagliptin and autoimmune disease in T2DM patients in Taiwan. Results showed that users of DPP-4 inhibitors had a decreased risk of composite autoimmune disease, including RA, psoriasis and AS compared with DPP-4i-naïve patients. In subgroup analysis, the inverse association of DPP-4 inhibitors with the incidence of autoimmune diseases is more significant in patients who were younger and had shorter duration of diabetes. In addition, regarding comparisons between the four commercially available DPP-4 inhibitors, differential AD predisposition between different types of DPP-4i users may be resulted from random variation because of their inconsistency. This was also the limit of data interpretation. As such, results of the present study provide clinical physicians with more information about treating patients with diabetes with DPP-4 inhibitors.

Apart from the metabolic effects, little has been investigated about the mechanism explaining the associations between the anti-diabetic DPP-4 inhibitors and autoimmune disease. Although there are already some epidemiologic reports regarding whether DPP-4 inhibitors would ameliorate autoimmune disease, the conclusion remained controversial.

Several studies have investigated the relationship between T lymphocyte cell surface-expressed DPP-4/CD26 activity and autoimmune disease. DPP-4/CD26 is expressed on various cell types, including T cells. In 2001, Steinbrecher et al. [30] used in vitro and vivo model to dissect the role of DPP-4/CD26 in the T cell homeostasis and demonstrated that administration of DPP-4 inhibitor significantly decreased and delayed clinical and neuropathological signs in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model.

Furthermore, in 2012, Professor Dandona et al. had demonstrated that sitagliptin could exert anti-inflammatory action by suppressing expression of proinflammatory genes in human samples. The mRNA expression in mononuclear cell of CD26, the proinflammatory cytokine, TNFα, the receptor for endotoxin, toll-like receptor (TLR)-4, TLR-2, and proinflammatory kinases, c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 and inhibitory-κB kinase (IKKβ), and that of the chemokine receptor CCR-2 fell significantly after 12 weeks of sitagliptin use [31]. There were several in vitro and in vivo evidences showing that the human DPP4 was correlated with susceptibility of infection. For examples, in 2013 Professor Raj et al. had identified human DPP-4 as the receptor for MERS-CoV that mediates infection [32]. Later in 2018, Prof. Fan also found the high susceptibility of infection by MERS-CoV in the transgene mouse model of global over-expression of human dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [33]. Taken together, these evidences showed that human DPP-4 (CD26) acted as key transmembrane glycoprotein that potentially mediated infection and inflammation. In addition, DPP-4i was generally considered to decrease chemotaxis, T cell immunity and lymphokines, which may act as the potential mechanism to reduce the incidence of autoimmune diseases. The above evidences were consistently correspondent with our findings that DPP-4 inhibitors users were correlated with the decreased incidence of autoimmune diseases as well as a decreased infection rate compared with non-DPP-4 inhibitors users in type 2 diabetic patients in our nationwide population-based cohort study.

Furthermore, human DPP-4 contains nine potential N-glycosylation sites, and the dynamic process of N-terminal sialylation appears to play an important role in the pathophysiology of autoimmune disease [8, 34]. Resting T cells were determined to be more sialylated than activated T cells. Hypersialylation has been associated with RA, SLE and aging. This might be one of the possible explanations of our subgroup analysis showing that patients who are younger and with shorter T2DM duration have more significant inverse association between DPP-4i and AD.

Another in vitro study showed that expression of DPP-4 as CD26 on the surface of keratinocytes and T cells in psoriatic skin is upregulated. Thus, DPP-4 inhibitors may improve psoriatic skin lesions by inhibiting activation of the T cells and possibly activate the anti-inflammatory protein expression hypothetically independent of the level of glycemic control [35].

There were also several human case reports and epidemiological studies evaluating the association between DPP-4i and autoimmune disorders, which was consistent with our findings. For example, a case report demonstrated that psoriatic skin lesions improved 3 months after introduction of sitagliptin in a 35-year-old patient with underlying psoriasis and T2DM [35]. In addition, another population-based study conducted by Kim et al. found that DPP-4 inhibitors may reduce the risk of RA and composite autoimmune disease [36]. Another population-based cohort study using Korean National Health Insurance Claims Database found that the risk of incident RA and composite AD was decreased for DPP4i initiators compared with non-DPP4i initiators, which was consistent with our findings [37]. Our cohort study, which had a follow-up period of 5 years between January 2009 and December 2013, is distinct because we included large Asian population (387,099 in DPP-4i group vs. 387,099 in DPP-4i-naive group). In addition, we also first demonstrated the detailed subgroup analysis regarding comorbidities, T2DM duration and prescription of anti-diabetic drugs. We are also the first to perform the comparison of HRs between four kinds of DPP-4 inhibitors and the analysis of dose-dependent response.

Some clinical studies had implicated that thiazolidinediones, also known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-r) agonist, have immunomodulating or anti-inflammatory action, resulting in beneficial effects on disease activity in T2DM patients with RA and psoriatic arthritis [38–40]. However, none of studies have investigated the interaction between CD26/DPP-4 and thiazolidinediones/PPAR-r agonist to date, which obviously needs more studies to delineate in the future based on our results.

Since the first DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin (trade name, Januvia) was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2006, more than one hundred meta-analyses have focused on the efficacy and safety of DPP-4-inhibitors [41–46]. Nevertheless, whether or not DPP-4 inhibitors will influence the T cell immune homeostasis or in turn decrease the risk of autoimmune disease in human has not reached a consensus. Results of the present study may have important implications for better understanding of the pathogenesis and its influences of DPP-4i-related autoimmune disease.

Our study focused on a relatively large Asian population evaluating DPP-4 inhibitors. We used propensity score matching to minimize selection bias in the two groups and to balance the most important variables, including T2DM duration and all available types of oral anti-hyperglycemic drugs. Another strict method of analysis—prescription time-distribution matching—may be able to eliminate survival bias and help make study results more reliable. Our study design used strict definitions of autoimmune diseases, using ICD-9-CM codes plus catastrophic illness certification for each outcome, with diagnoses confirmed by two rheumatologists.

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. First, some of the confounding factors associated with autoimmune diseases are difficult to control, such as genetics, infection, environment, smoking, nutritional status, or physicians’ clinical judgment and preference of drugs based on disease severity. Although we included a wide range of variables such as comorbidities and non-studied medications using the claims data from 12 months prior to the index date to balance the two groups, a 12-month period may not be long enough to detect all baseline information of the potential confounders associated with autoimmune disease. Second, the severity of T2DM could not be evaluated properly because no biochemistry data were available. Nevertheless, we matched the T2DM diagnosis duration and glucose-lowering medications between the two groups, finding that the T2DM severity is relatively equal between the groups. Third, we relied on diagnosis codes without available images, laboratory data or disease-specific immunomodulating medications prescriptions for the outcomes. In order to strengthen ascertainment, we also identified catastrophic illness certification for each outcome. Nevertheless, several autoimmune diseases such as autoimmune thyroiditis were not fit for catastrophic illness certificate in Taiwan, which was absolutely definite in differentiation of etiology of each diagnosis of rare diseases. Therefore, it is difficult to differentiate the etiology of autoimmune thyroid disease solely from the ICD-9-CM codes recorded in the NHI research database in spite of the confirmation by laboratory results of thyroid-related autoantibody in the current study designs.

Therefore, future prospective studies are needed with a longer follow-up periods of surveillance to elucidate the potential risks and causal effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on immunological side effects or to further survey the absolute cumulative dose effect of DPP-4i on autoimmune disorders.

In conclusion, DPP-4 inhibitors decreased risk of autoimmune diseases in T2DM patients in Taiwan compared with those not receiving DPP-4 inhibitors. Those who were younger and with the lesser duration of diagnosis would benefit more from the immune homeostasis of DPP-4i according to this study. Results of this study provide clinical physicians with useful information regarding the use of DPP-4 inhibitors in treating patients with diabetes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Tien-Hsing Chen and Yi-Wen Tsai contributed equally as corresponding authors to this work. The authors wish to acknowledge the Maintenance Project of the Biostatistical Consultation Center (Grants CLRPG2C0021, CLRPG2C0022, CLRPG2C0023, CLRPG2C0024, CLRPG2G0081) at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung Branch, for assistance with study design and monitoring, data analysis and interpretation.

Authors contribution

YCC, THC and YWT conceived of the study concept and developed the study design. SCC, SSC and YL were responsible for the statistical analysis. YCC, JYC, THC and YWT were responsible for data collection. YCC drafted the manuscript. THC and YWT was responsible for the data interpretation and revised the final draft. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data availability

This study is based on data from the diabetes subsection of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by National Health Research Institutes. Any use of the raw data required a license agreement with the Bureau of National Health Insurance.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Human and animal rights

The protocol performed in this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The protocol of this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study was approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (201700350B0).

Informed consent

The institutional review board of Chang Gung Medical Foundation determined that patient consent was not required because all data were anonymized by the data holder, the Taiwan National Health Insurance Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Amori RE, Lau J, Pittas AG. Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298(2):194–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karagiannis T, Paschos P, Paletas K, Matthews DR, Tsapas A. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the clinical setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e1369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambeir AM, Durinx C, Scharpe S, De Meester I. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from bench to bedside: an update on structural properties, functions, and clinical aspects of the enzyme DPP IV. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40(3):209–294. doi: 10.1080/713609354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sedo A, Duke-Cohan JS, Balaziova E, Sedova LR. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity and/or structure homologs: contributing factors in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(6):253–269. doi: 10.1186/ar1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drucker DJ, Nauck MA. The incretin system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;368(9548):1696–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69705-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohnuma K, Hosono O, Dang NH, Morimoto C. Dipeptidyl peptidase in autoimmune pathophysiology. Adv Clin Chem. 2011;53:51–84. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385855-9.00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinhold D, Hemmer B, Gran B, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26): role in T cell activation and autoimmune disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;477:155–160. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemann C, Wagner L, Stephan M, von Horsten S. Cut to the chase: a review of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase-4’s (DPP4) entanglement in the immune system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;185(1):1–21. doi: 10.1111/cei.12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotoh H, Hagihara M, Nagatsu T, Iwata H, Miura T. Activities of dipeptidyl peptidase II and dipeptidyl peptidase IV in synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Clin Chem. 1989;35(6):1016–1018. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/35.6.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamori M, Hagihara M, Nagatsu T, Iwata H, Miura T. Activities of dipeptidyl peptidase II, dipeptidyl peptidase IV, prolyl endopeptidase, and collagenase-like peptidase in synovial membrane from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1991;45(2):154–160. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(91)90016-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muscat C, Bertotto A, Agea E, et al. Expression and functional role of 1F7 (CD26) antigen on peripheral blood and synovial fluid T cells in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;98(2):252–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordero O, Salgado F, Mera-Varela A, Nogueira M. Serum interleukin-12, interleukin-15, soluble CD26, and adenosine deaminase in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2001;21(2):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s002960100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuchacovich M, Gatica H, Pizzo SV, Gonzalez-Gronow M. Characterization of human serum dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) and analysis of its autoantibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2001;19(6):673–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong PT, Wong CK, Tam LS, Li EK, Chen DP, Lam CW. Decreased expression of T lymphocyte co-stimulatory molecule CD26 on invariant natural killer T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Invest. 2009;38(5):350–364. doi: 10.1080/08820130902770003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bock O, Kreiselmeyer I, Mrowietz U. Expression of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD26) on CD8+ T cells is significantly decreased in patients with psoriasis vulgaris and atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(6):414–419. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hildebrandt M, Rose M, Ruter J, Salama A, Monnikes H, Klapp BF. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DP IV, CD26) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(10):1067–1072. doi: 10.1080/003655201750422675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoury SJ, Guttmann CR, Orav EJ, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, Weiner HL. Changes in activated T cells in the blood correlate with disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2000;57(8):1183–1189. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.8.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ospelt C, Mertens JC, Jungel A, et al. Inhibition of fibroblast activation protein and dipeptidylpeptidase 4 increases cartilage invasion by rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(5):1224–1235. doi: 10.1002/art.27395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busso N, Wagtmann N, Herling C, et al. Circulating CD26 is negatively associated with inflammation in human and experimental arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(2):433–442. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62266-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamauchi K, Sato Y, Yamashita K, et al. RS3PE in association with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor: report of two cases. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):e7. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasaki T, Hiki Y, Nagumo S, et al. Acute onset of rheumatoid arthritis associated with administration of a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitor to patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Int. 2010;1(2):90–92. doi: 10.1007/s13340-010-0010-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokota K, Igaki N. Sitagliptin (DPP-4 inhibitor)-induced rheumatoid arthritis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a case report. Intern Med. 2012;51(15):2041–2044. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crickx E, Marroun I, Veyrie C, et al. DPP4 inhibitor-induced polyarthritis: a report of three cases. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(2):291–292. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2710-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yazbeck R, Howarth GS, Abbott CA. Dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitors, an emerging drug class for inflammatory disease? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30(11):600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Yuan J, Zhou Z. Emerging roles of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors: anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effect and its application in diabetes mellitus. Can J Diabetes. 2014;38(6):473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng SH, Chiang TL. The effect of universal health insurance on health care utilization in Taiwan. Results from a natural experiment. JAMA. 1997;278(2):89–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng TM. Taiwan’s new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(3):61–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin CC, Lai MS, Syu CY, Chang SC, Tseng FY. Accuracy of diabetes diagnosis in health insurance claims data in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(3):157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu CS, Lai MS, Gau SS, Wang SC, Tsai HJ. Concordance between patient self-reports and claims data on clinical diagnoses, medication use, and health system utilization in Taiwan. PloS One. 2014;9(12):e112257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinbrecher A, Reinhold D, Quigley L, et al. Targeting dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) suppresses autoimmune encephalomyelitis and up-regulates TGF-beta 1 secretion in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;166(3):2041–2048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makdissi A, Ghanim H, Vora M, et al. Sitagliptin exerts an antinflammatory action. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3333–3341. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature. 2013;495(7440):251–254. doi: 10.1038/nature12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan C, Wu X, Liu Q, et al. A human DPP4-knockin mouse’s susceptibility to infection by authentic and pseudotyped MERS-CoV. Viruses. 2018 doi: 10.3390/v10090448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slimane TA, Lenoir C, Sapin C, Maurice M, Trugnan G. Apical secretion and sialylation of soluble dipeptidyl peptidase IV are two related events. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258(1):184–194. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishioka T, Shinohara M, Tanimoto N, Kumagai C, Hashimoto K. Sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitor, improves psoriasis. Dermatology. 2012;224(1):20–21. doi: 10.1159/000333358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SC, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Doherty M, Goldfine AB, Solomon DH. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes may reduce the risk of autoimmune diseases: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(11):1968–1975. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seong JM, Yee J, Gwak HS. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors lower the risk of autoimmune disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85(8):1719–1727. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahin D, Toraby EE, Abdel-Malek H, Boshra V, Elsamanoudy AZ, Shaheen D. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist (pioglitazone) and methotrexate on disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (experimental and clinical study) Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;4:1–10. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ormseth MJ, Oeser AM, Cunningham A, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist effect on rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R110. doi: 10.1186/ar4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bongartz T, Coras B, Vogt T, Scholmerich J, Muller-Ladner U. Treatment of active psoriatic arthritis with the PPARgamma ligand pioglitazone: an open-label pilot study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(1):126–129. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(3):232–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheen AJ, Paquot N. TECOS: confirmation of the cardiovascular safety of sitaliptin. Rev Med Liege. 2015;70(10):511–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engel SS, Round E, Golm GT, Kaufman KD, Goldstein BJ. Safety and tolerability of sitagliptin in type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of 25 clinical studies. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(1):119–145. doi: 10.1007/s13300-013-0024-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams-Herman D, Engel SS, Round E, et al. Safety and tolerability of sitagliptin in clinical studies: a pooled analysis of data from 10,246 patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2010;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao M, Chen J, Yuan Y, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8273. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07921-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1317–1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study is based on data from the diabetes subsection of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by National Health Research Institutes. Any use of the raw data required a license agreement with the Bureau of National Health Insurance.