Abstract

Background

Caesarean section increases the risk of postpartum infection for women and prophylactic antibiotics have been shown to reduce the incidence; however, there are adverse effects. It is important to identify the most effective class of antibiotics to use and those with the least adverse effects.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the balance of benefits and harms between different classes of antibiotic given prophylactically to women undergoing caesarean section.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (30 September 2014) and reference lists of retrieved papers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials comparing different classes of prophylactic antibiotics given to women undergoing caesarean section. We excluded trials that compared drugs with placebo or drugs within a specific class; these are assessed in other Cochrane reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and carried out data extraction.

Main results

We included 35 studies of which 31 provided data on 7697 women. For the main comparison between cephalosporins versus penicillins, there were 30 studies of which 27 provided data on 7299 women. There was a lack of good quality data and important outcomes often included only small numbers of women.

For the comparison of a single cephalosporin versus a single penicillin (Comparison 1 subgroup 1), we found no significant difference between these classes of antibiotics for our chosen most important seven outcomes namely: maternal sepsis ‐ there were no women with sepsis in the two studies involving 346 women; maternal endometritis (risk ratio (RR) 1.11, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.52, nine studies, 3130 women, random effects, moderate quality of the evidence); maternal wound infection (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.81, nine studies, 1497 women, random effects, low quality of the evidence), maternal urinary tract infection (RR 1.48, 95% CI 0.89 to 2.48, seven studies, 1120 women, low quality of the evidence) and maternal composite adverse effects (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.18 to 21.96, three studies, 1902 women, very low quality of the evidence). None of the included studies looked for infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

This meant we could only conclude that the current evidence shows no overall difference between the different classes of antibiotics in terms of reducing maternal infections after caesarean sections. However, none of the studies reported on infections diagnosed after the initial postoperative hospital stay. We were unable to assess what impact, if any, the use of different classes of antibiotics might have on bacterial resistance.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the best currently available evidence, cephalosporins and penicillins have similar efficacy at caesarean section when considering immediate postoperative infections. We have no data for outcomes on the baby, nor on late infections (up to 30 days) in the mother. Clinicians need to consider bacterial resistance and women's individual circumstances.

Plain language summary

Comparing different types of antibiotics given routinely to women at caesarean section to prevent infections

Background

Women undergoing caesarean section have an increased likelihood of infection compared with women who give birth vaginally. These infections can be in the urine, surgical incision, or the lining of the womb (endometritis). The infections can become serious, causing, for example, an abscess in the pelvis or infection in the blood, and very occasionally can lead to the mother's death. Sound surgical techniques are important for reducing infections, along with skin antiseptics and antibiotics. However, antibiotics can cause adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, skin rash and rarely allergic reactions in the mother, and the risk of thrush (candida) for the mother and the baby. Antibiotics, given to women around the time of giving birth, can also change the baby's gut flora and thus may interfere with the baby's developing immune system.

Our review question

We asked if cephalosporin antibiotics were better than penicillins for women having a caesarean section. We also looked to see how other groups of antibiotics compared.

What we found

When comparing cephalosporins against penicillins, we found 27 studies, involving 7299 women as of September 2014. The quality of the studies was generally unclear and three studies reported drug company funding. Cephalosporins and penicillins had similar effects in reducing infections after caesareans and similar adverse effects. However, none of the studies considered infections after the women left hospital. None of the studies looked at outcomes on the babies. Other evidence show tetracyclines can cause discolouration of teeth in children and are best avoided. Consideration also needs to be given to antibiotics compatible with breastfeeding. We were unable to assess bacterial resistance, and this is crucial when considering which antibiotic might be used.

What our results mean

At caesarean sections, cephalosporins and penicillins have similar benefits and side effects for mothers when considering infections immediately following the operation but there is no information on babies. Clinicians need to consider bacterial resistance and women's individual circumstances.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women for preventing infection at caesarean section.

| Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women for preventing infection at caesarean section | ||||||

| Population: Women undergoing caesarean section. Settings: Hospitals in Sudan, US, Thailand, Italy, Zimbabwe, Mozanbique, Switzerland, South Africa, Canada, Rwanda, Malaysia, Finland, United Arab Emirates, Netherlands, Argentina, UK, Greece. Intervention: Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women. | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women | |||||

| Maternal sepsis ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 346 (2 studies) | See comment | The outcome was reported with no events. |

| Maternal endometritis ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | Study population | RR 1.11 (0.81 to 1.52) | 3130 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 109 per 1000 | 121 per 1000 (88 to 165) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 86 per 1000 | 95 per 1000 (70 to 131) | |||||

| Infant sepsis ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | This outcome was not reported in any of the included studies. |

| Infant oral thrush ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | This outcome was not reported in any of the included studies. |

| Maternal wound infection ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.38 to 1.81) | 1497 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 33 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (12 to 59) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 34 per 1000 | 28 per 1000 (13 to 62) | |||||

| Maternal urinary tract infection ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | Study population | RR 1.48 (0.89 to 2.48) | 1120 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| 49 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (43 to 121) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 37 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (33 to 92) | |||||

| Maternal composite adverse effects ‐ Single cephalosporin vs single penicillin | Study population | RR 2.02 (0.18 to 21.96) | 1902 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4 | ||

| 2 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (0 to 47) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Most studies contributing data had design limitations. 2 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect & small sample size. 3 One study with design limitations. 4 Wide confidence interval crossing the line of no effect & few events.

Background

Women undergoing caesarean section have an increased risk of postoperative infection and infectious morbidity compared with women giving birth vaginally (Declercq 2007). Since caesarean section rates are in excess of 20% in many high‐income countries, these infections are a major concern.

Description of the condition

Caesarean sections have been shown to have nearly five times the risk of postpartum infection as vaginal births (and this is with a policy of antibiotics at caesarean section) and just over 75% occur after hospital discharge (Leth 2009). The infectious complications that can occur after caesarean birth include infections of the wound/incision, endometritis (infection of the lining of the uterus) and urinary tract infection, although fever can occur after any operation and is not necessarily an indicator of infection (MacLean 1990). However, there can occasionally be more serious infectious complications such as pelvic abscess (collection of pus in the pelvis), bacteraemia (bacterial infection in the blood), septic shock (reduced blood volume due to infection), necrotising fasciitis (tissue destruction in the abdominal wall) and septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis (inflammation and infection of the veins in the pelvis). These more serious infectious complications can lead to maternal mortality.

Description of the intervention

The potential for prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the incidence of maternal infectious morbidity following caesarean section has now been systematically investigated (Smaill 2002; Smaill 2008). Although evidence has existed for some time to support this practice (Pedersen 1996), it is not clear whether any one particular agent, dose or route of administration is superior. Many different drug regimens have been reported to be effective in decreasing immediate postoperative infectious morbidity. To date, various penicillins (ampicillin, ticarcillin, mezlocillin, piperacillin), cephalosporins (cefazolin, cephalothin, ceforanide, cefonicid, cefuroxime, ceftazidime, cefoxitin, cefamandole, cephradine, cefotetan, cefotaxime), fluoroquinolones etc. have been used for caesarean section prophylaxis and overall they have demonstrated some efficacy either alone or in combination with another drug (Smaill 2008). Some of these drugs have activity against a narrow range of potential pathogens (e.g. metronidazole, gentamicin), others have additional specific anaerobic activity (e.g. cefoxitin and cefotetan), and yet others have very broad‐spectrum coverage (imipenem). Their pharmacokinetic properties (e.g. serum half‐life) also differ. Some drugs used in the past are now associated with bacterial resistance.

In addition to the choice of drug there are differences in the route of administration and the timing of administration of prophylactic antibiotics. As well as systemic administration (intravenous and intramuscular), use of intra‐operative irrigation of the uterus and peritoneal cavity with an antibiotic solution has been reported. While some guidelines recommend multiple doses of antibiotics, a single dose at the time of the procedure may be adequate. These considerations will be covered in other Cochrane reviews ‐ see Differences between protocol and review for details.

How the intervention might work

Since penicillin was introduced during the 1940s, scientists have developed numerous other antibiotics. Today, over 100 different antibiotics are available. For the prevention of surgical infections it is generally considered that sound surgical technique is important along with skin antiseptics and the use of antibiotics (Owen 1994). Antibiotics act by either killing bacteria (bacteriocidal) or inhibiting bacterial replication (bacteriostatic) but the large variety of different types of bacteria mean a large variety of possible antibiotics may be used.

Classification of antibiotics

Antibiotics can be classified in a number of ways, but classifying by chemical structure is useful because antibiotics within a structural class will generally have similar patterns of effectiveness, toxicity and allergic potential (Bayarski 2006; eMedExpert 2009; Goodman 2008). The most commonly used types of antibiotics are penicillins, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and macrolides, with each class including many drugs (Table 17). Penicillins have a common structure which they share with cephalosporins. Both classes of antibiotics are bactericidal, acting through inhibiting cell wall synthesis. Penicillins are grouped into four types and cephalosporins are grouped into four generations with each newer generation having a broader spectrum of activity (eMedExpert 2009). Fluoroquinolones are the newest class of antibiotics and are synthetic rather than derived from bacteria. These newer fluoroquinolones are broad‐spectrum bacteriocidal drugs chemically unrelated to penicillins or cephalosporins. They interfere with the ability of bacteria to make DNA. Tetracyclines are derived from streptomyces bacteria and are broad‐spectrum bacteriostatic antibiotics. Macrolides are also derived from streptomyces bacteria and are also bacteriostatic in action, binding to bacterial ribosomes. Aminoglycosides are used to treat gram‐negative bacteria and may be used alongside penicillins and cephalosporins (eMedExpert 2009).

1. Classification of antibiotics.

| A. Penicillins | Penicillins consist of a thiazolidine ring connected to a B‐lactam ring to which is attached a side chain. The penicillin nucleus itself is the chief structural requirement for biological activity. Penicillins are the oldest class of antibiotics and function by inhibiting cell wall synthesis (bactericidal). A1. Natural penicillins are based on the original penicillin‐G structure. Examples include: penicillin G; procaine, penicillin V; benzathine. A2. Penicillinase‐resistant penicillins are active even in the presence of the bacterial enzyme that inactivates most natural penicillins. Examples include: cloxacillin; dicloxacillin; methicillin; nafcillin; oxacillin. A3. Extended spectrum penicillins which are effective against a wider range of bacteria. Examples include: ticarcillin; piperacillin; carbenicillin; timentin. A4. Aminopenicillins also have an extended spectrum of action compared with the natural penicillins. Examples include: ampicillin; amoxicillin. A+. Penicillin combinations. Examples include: co‐amoxyclav = 'ampicillin+ clavulanic acid' (Trade names include: Augmentin; Clavamox; Tyclav); 'ampicillin + sulbactam' (Trade names include: Ampictam; Unasyn). |

| B. Cephalosporins | Cephalosporins have a similar basic structure to penicillins but with different side chains. They function by inhibiting cell wall synthesis. B1. First generation cephalosporins; examples include: cephalothin; cefazolin; cephapirin; cephradine; cephalexin; cefadroxil. B2. Second generation cephalosporins; examples include: cefoxitin; cefaclor; cefuroxime; cefotetan; cefprozil; cefamandole, cefonicid; ceforanide, cefotiam. B3. Third generation cephalosporins, examples include: cefotaxime; ceftizoxime; ceftriaxon; cefpodoxime; cefditoren; ceftibuten; ceftazidine; cefcapene; cefdaloxime; cefetamet; cefixime; cefmenoxime; cefodizime; cefoperazone; cefpimizole. B4. Fourth generation cephalosporins, examples include: cefepime; cefpirome; cefclidine; cefluprenam; cefozopran; cefquinome. B+: Cephalosporin combinations. Examples include: 'cephradine + metronidazole'; 'ceftriaxone + metronidazole'; 'cloxacillin + gentamicin'. |

| C. Fluoroquinolones | The fluoroquinolones target the bacterial DNA gyrase and topoisomerase. They are potent bacteriocidal agents against a broad variety of micro‐organisms. Examples include: ciprofloxacin; levofloxacin; lomefloxacin; norfloxacin; sparfloxacin; clinafloxacin; gatifloxacin; ofloxacin; trovafloxacin. |

| D. Tetracyclines | Tetracyclines are bacteriostatic antibiotics active against a wide range of aerobes and anaerobic gram‐positive and gram‐negative bacteria. They inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 30S bacterial ribosome. Examples include: tetracycline; doxycycline; minocycline. Tetracyclines should not be used with children under 8 and specifically during teeth development as they can cause a permanent brown discolouration to the teeth. This antibiotic is, therefore, unlikely to be used at caesarean section. Chloramphenicol is considered to have similar action to tetracycline. |

| E. Macrolides | Macrolide antibiotics inhibit bacterial protein synthesis. Resistance can arise. Examples include: erythromycin; clarithromycin; azithromycin. |

| F. Other beta‐lactams (carbapenems) | Carbapenems are beta‐lactams that have a broader spectrum of activity than most other beta‐lactam antibiotics. Examples include: imipenem; meropenem; ertapenem; aztreonam, mezlocillin. |

| G. Aminoglycosides | Aminoglycosides are first‐line therapy for a limited number of very specific, often historically prominent infections, such as plague, turaremia and tuberculosis. Examples include: streptomycin; gentamicin, kanamycin. |

| H. Lincosamides | Lincosamides are protein synthesis inhibitors which bind to the 50s subunit of bacterial ribosomes and inhibit early elongation of peptide chain by inhibiting transpeptidase reaction. Examples include: lincomycin; clindamycin. |

| I. Nitroimidazoles | Nitroimidazole is an imidazole derivative that contains a nitro group. It is used for the treatment of infection with anaerobic organisms. Examples include: metronidazole, tinidazol. |

| J. Others |

SeeGoodman 2008 for more detailed information about the classification and BNF 2009. Also from Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org/)

Potential adverse effects of antibiotics

On the mother

The benefits of antibiotics are well‐known, but there are potential adverse effects which also need to be considered. Antibiotic use is associated with some gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea), skin rashes, thrush/candidiasis (infection with candida which can affect both mother and baby), and joint pain (Dancer 2004). Occasionally there can also be blood problems, or kidney or liver damage (Dancer 2004; Westphal 1994), and very occasionally anaphylaxis (a hypersensitivity reaction leading to pallor, shock and collapse, which is sometimes fatal). Possible interactions with other drugs the mother may be taking also need to be considered.

On the infant

Some antibiotics can reach the baby during labour or through breastfeeding, and these may upset the pattern of friendly bacterial flora being established in the baby's gut as part of the baby's immune system (Bedford Russell 2006; Penders 2006). There is evidence that this impact can continue for up to six months after birth (Grolund 1999) and the consequences of this may occasionally be late‐onset serious bacterial infections (Glasgow 2005). It has been proposed that perinatal exposure to certain agents can cause irreversible changes to health conditions in adulthood through impact on hormonal imprinting (Csaba 2007; Tchernitchin 1999). It is also possible that babies born prematurely, with less mature immune systems, may be affected more.

Drug‐resistant strains of antibiotics

Resistance of bacteria to antibiotics is spreading and develops when a strain of bacteria evolves which is not destroyed by the antibiotic. The antibiotic kills off the non‐resistant bacteria allowing the resistant ones to colonise and spread. Widespread use of antibiotics can contribute to the development of drug‐resistant strains of bacteria, which means that these antibiotics become ineffective because of bacterial resistance (Dancer 2004). At a population level this is a critical problem which may cause increase in serious morbidity from hospital‐acquired drug‐resistant infections (Dancer 2004). The use of antibiotics in other areas of maternity care, e.g. anti‐Group B streptococcus prophylaxis, contribute further to this problem. This drug resistance is unlikely to be detected in randomised controlled trials and other types of research are needed to assess the potential problem of drug‐resistant strains (e.g. MRSA (Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus), C difficile) in hospitals. The dose and number of antibiotic administrations given are a major consideration in relation to antibiotic resistance. These issues will be addressed in the other reviews ‐ seeDifferences between protocol and review for details.

Why it is important to do this review

Since there are an overwhelming number of effective drugs available, attempts to define an antibiotic regimen of choice have been problematic. Ideally, such a drug regimen should be: (1) proven to be effective in well‐designed prospective, randomised, double‐blind clinical trials, (2) active against the majority of pathogens likely to be involved, (3) able to attain adequate serum and tissue levels throughout the procedure, (4) not associated with the development of antimicrobial resistance, (5) inexpensive, and (6) well‐tolerated. In many respects penicillins and cephalosporins meet these criteria. Many investigators have used these drugs and have recommended that drugs from these classes represent the antibiotics of choice for caesarean section prophylaxis (Cartwright 1984). However, current knowledge of bacterial resistance may challenge these recommendations.

The past several decades have seen an increase in the incidence of caesarean section, associated with an increase in maternal postoperative infection. Studies indicate that wound infection can be as high as 30% and endometritis as high as 60% where prophylactic antibiotics have not been utilised (Smaill 2002). Therefore, infectious complications that occur following caesarean section are an important contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality (Henderson 1995). Such complications are also an important source of increased hospital stay and consumption of financial resources. Prophylactic antibiotics for caesarean section can be expected to result in a major reduction in postoperative infectious morbidity. The question that remains, therefore, is which regimen to use.

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the balance of benefits and harms between different class of antibiotic given prophylactically to women undergoing caesarean section, considering the effectiveness in reducing infectious complications for women and adverse effects on both mother and infant.

Other Cochrane reviews will address: effectiveness against placebo (Smaill 2008), dosage by the various classes of antibiotics, different routes of administration and various timings of administration.

We will consider factors that may affect antibiotic resistance in a future update of this review.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) where the intention was to allocate participants randomly to one of at least two alternative classes of regimens of antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section. We excluded quasi‐RCTs. Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion but none were identified. Cross‐over trials were not eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Women undergoing caesarean section, both elective and non‐elective.

Types of interventions

Prophylactic antibiotic regimens comparing different classes of antibiotics. We included studies where there was a comparison between two or more antibiotics from the different classes of antibiotics.

We excluded comparisons of different drugs within the same class of antibiotics as these will be assessed in other Cochrane reviews.

Different regimens of penicillin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section

Different regimens of cephalosporin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section

Assessment of the appropriate timing and route of administration of prophylactic antibiotics will also be considered in further reviews.

Timing of prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section

Routes of administration for antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal

Maternal sepsis (suspected or proven)

Endometritis

Infant

Infant sepsis (suspected or proven)

Oral thrush

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Fever (febrile morbidity)

Wound infection

Urinary tract infection

Thrush

Serious infectious complication (such as bacteraemia, septic shock, septic thrombophlebitis, necrotising fasciitis, or death attributed to infection)

Adverse effects of treatment on the woman (e.g. allergic reactions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, skin rashes)

Maternal length of hospital stay

Infections ‐ post‐hospital discharge to 30 days postoperatively (not pre‐specified in the protocol)

Readmissions (not pre‐specified in the protocol)

Infant

Immediate adverse effects of antibiotics on the infant (unsettled, diarrhoea, rashes)

Infant length of hospital stay

Long‐term adverse effects (e.g. general health, frequency of visits to hospital)

Infant's immune system development (using a validated scoring assessment)

Additional outcomes

Development of bacterial resistance

Costs

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (30 September 2014).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of Embase;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and Embase, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists at the end of papers for further studies.

We did not apply any language or date restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, please see Alfirevic 2010.

For this update, the following methods were used. These methods are based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager software (RevMan 2014) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2011). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses ‐ seeSensitivity analysis.

For this update the quality of the evidence assessed using the GRADE approach (Schunemann 2009) in order to assess the quality of the body of evidence relating to the following key outcomes for the main comparison first subgroup, single cephalosporins versus single penicillins:

Maternal sepsis

Maternal endometritis

Infant sepsis

Infant oral thrush

Wound infection

Maternal urinary tract infection

Maternal composite adverse effects (e.g. allergic reactions; nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, skin rashes)

GRADE profiler (GRADE 2008) was used to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014) in order to create ’Summary of findings’ tables. A summary of the intervention effect and a measure of quality for each of the above outcomes was produced using the GRADE approach. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence can be downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments for risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

We used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We planned to use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

Had we identified any cluster‐RCTs we would have included them in the analyses along with individually‐randomised trials, following the methods described in Higgins 2009 and the Handbook [Section 16.3.4 or 16.3.6] using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. If we use ICCs from other sources, we will report this and conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. In future updates, if we identify both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, we plan to synthesise the relevant information. We will consider it reasonable to combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit is considered to be unlikely.

We will also acknowledge heterogeneity in the randomisation unit and perform a sensitivity subgroup analysis to investigate the effects of the randomisation unit.

Other unit of analysis issues

No special methods were used for trials with more than one treatment group.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. In future updates, if more eligible studies are included, the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect will be explored by using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes, analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention‐to‐treat basis i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if the Tau² was greater than zero or the I² was greater than 30% and there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. Had we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where there were 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry was suggested by a visual assessment, we explored possible reasons for this.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2014). We used fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar.

Where there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis to produce an overall summary, if an average treatment effect across trials was considered clinically meaningful. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect was not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. If we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We analysed separately, for all outcomes, penicillins and cephalosporins given alone as opposed to when they were given in combination with other drugs, for the main comparison of cephalosporins versus penicillins (Comparison 1).

We carried out the following subgroup analyses for the main comparison between penicillins and cephalosporins only and for primary outcomes only.

By type of surgery: elective caesarean section versus non‐elective caesarean section versus mixed or not defined. (Rupture of membranes for more than six hours or the presence of labour was used to differentiate a non‐elective caesarean section from an elective procedure.)

By time of administration: before cord clamping versus after cord clamping versus not defined.

By route of administration: systemic versus lavage.

We intended to undertake a subgroup analysis by the number of doses given but feel this is better assessed in other reviews (Different regimens of penicillin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section and Different regimens of cephalosporin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section). There will also be a review or reviews on the timing and routes of administration of the antibiotics where studies exist which compare directly, for example, before and after cord clamping (Timing of prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section and Routes of administration for antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section).

We assessed subgroup differences by interaction tests (Deeks 2001) available within RevMan (RevMan 2014). We reported the results of subgroup analyses quoting the Chi² statistic and P value, and the interaction test I² value.

Sensitivity analysis

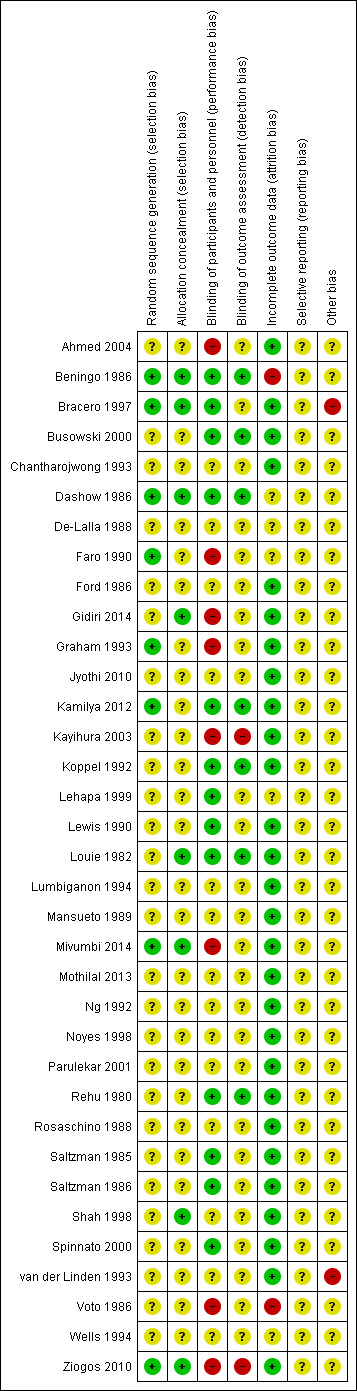

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there was a high risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality, for example, inadequate sequence generation and allocation concealment (Schultz 1995), we planned to explore this by sensitivity analysis (Higgins 2009) but we felt there were insufficient high‐quality trials (only three identified Figure 1) for a meaningful analysis.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 136 reports for 133 studies. For a detailed description of studies seeCharacteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

The 35 trials included in the review were conducted mostly in industrialised countries, for example, United States, Canada, Israel, Italy, Switzerland or The Netherlands (see Characteristics of included studies).. Criteria listed to define the presence of outcome variables of interest (e.g. endometritis) were remarkably consistent across trials.

Two studies await data extraction, either because they are being translated or we are awaiting information from the authors (see Studies awaiting classification).

Included studies

We included 35 studies, of which 31 provided data involving 7697 women and we undertook 37 meta‐analyses. Four studies were reported as conference abstracts only (De‐Lalla 1988; Lehapa 1999; Lumbiganon 1994; Wells 1994). Four studies did not provide data: two full papers (Graham 1993; Voto 1986) and two of the conference abstracts (De‐Lalla 1988; Wells 1994). Antibiotics for prophylaxis were administered after the cord was clamped in all but five of the studies, where four administered the prophylaxis before cord clamping (Ahmed 2004; Mivumbi 2014; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988) and one study did not provide the information (Gidiri 2014).

Cephalosporins versus penicillins

We included 30 studies, of which 27 provided data on 7299 women, where cephalosporins were compared with penicillins for prophylaxis at caesarean section (Ahmed 2004; Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Gidiri 2014; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lehapa 1999; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Mivumbi 2014; Ng 1992; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010). Four studies were included though they provide no usable data on the outcomes listed in the review (De‐Lalla 1988; Graham 1993; Voto 1986).

We looked at comparisons of the subgroups of :

single cephalosporins versus single penicillins

single cephalosporins versus penicillin combinations (e.g. co‐amoxyclav)

cephalosporin combinations versus single penicillins

cephalosporin combinations versus penicillin combinations

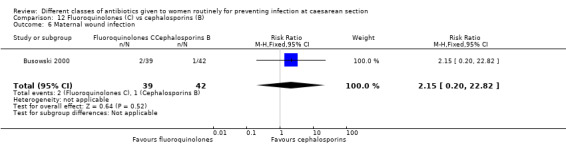

Other antibiotic classes

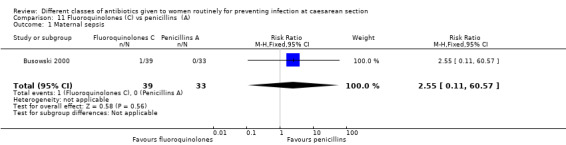

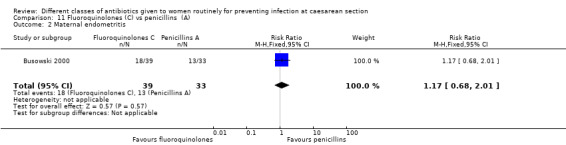

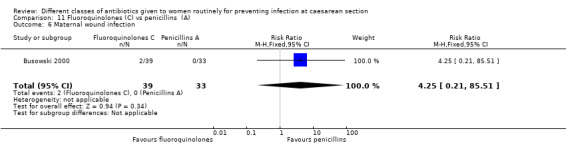

We found three studies comparing a cephalosporin or penicillin with another class of antibiotics (Busowski 2000; Mothilal 2013; Wells 1994).

Mixed antibiotics regimens that did not include cephalosporins versus penicillins

We included a further five studies that assessed other combined antibiotic regimens against penicillins or cephalosporins for prophylaxis at caesarean section (Kayihura 2003; Mansueto 1989; Mothilal 2013; Rehu 1980; Shah 1998 ) and one study already included which also compared a combination of other antibiotics with a cephalosporin (Parulekar 2001).

Excluded studies

We excluded 96 studies that compared different antibiotics within the same class, either singly or in combination (seeCharacteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 1 for a summary of 'Risk of bias' assessments.

Allocation

Five studies were considered to have adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment (Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014; Ziogos 2010). Three further studies were assessed as low risk of bias for sequence generation but were unclear on allocation concealment (Faro 1990; Graham 1993; Kamilya 2012). The remaining studies were unclear about how adequately they had addressed these aspects to minimise bias.

Blinding

Thirteen studies were assessed as low risk of bias for performance bias (Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Dashow 1986; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lehapa 1999; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Rehu 1980; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Spinnato 2000), eight were assessed as high risk (Ahmed 2004; Faro 1990; Gidiri 2014; Graham 1993; Kayihura 2003; Mivumbi 2014; Voto 1986; Ziogos 2010) and the remainder were unclear.

For detection bias, we assessed seven studies as low risk (Beningo 1986; Busowski 2000; Dashow 1986; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Louie 1982; Rehu 1980), two as high risk (Kayihura 2003; Ziogos 2010) and the remainder as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Twenty‐eight studies were assessed as low risk of attrition bias (Ahmed 2004; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Ford 1986; Gidiri 2014; Graham 1993; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Kayihura 2003; Koppel 1992; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Mansueto 1989; Mivumbi 2014; Mothilal 2013; Ng 1992; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rehu 1980; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010).

Selective reporting

This was unclear on all the included studies as we were not able to assess the trial protocols.

Other potential sources of bias

This was assessed as unclear for all but two of the included studies; many of the studies were quite old and it was difficult to assess if there were other biases. The two studies assessed as having high risk of other bias were studies funded by drug companies (Bracero 1997; van der Linden 1993). In one study the antibiotic drugs were donated by the drug company but this was considered not to necessarily increase the likelihood of bias (Ahmed 2004). The other included studies gave no mention of drug company involvement.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The search identified 35 studies of which 31 provided data in a format that could be included in this review (Ahmed 2004; Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Gidiri 2014; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Kayihura 2003; Koppel 1992; Lehapa 1999; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Mansueto 1989; Mivumbi 2014; Mothilal 2013; Ng 1992; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rehu 1980; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010). These studies included 7697 women. A further four studies also addressed the comparisons in this review but did not provide data that could be included in the meta‐analyses (De‐Lalla 1988; Graham 1993; Voto 1986; Wells 1994).

The classification of antibiotics is set out in Additional tables.

1. Cephalosporins (B) versus penicillins (A) ‐ all women, 27 studies, 7299 women

Twenty‐seven studies provided data for inclusion in this comparison (Ahmed 2004; Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Gidiri 2014; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lehapa 1999; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Mivumbi 2014; Ng 1992; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010 ). A further four studies addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (De‐Lalla 1988; Graham 1993; Voto 1986; Wells 1994).

Overall, the quality of studies was generally unclear for the critical aspects of selection bias, probably reflecting that they were mostly older studies undertaken in the 1980s and 1990s. Only five studies met the criteria for low risk of bias in terms of sequence generation and allocation concealment (Beningo 1986; Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014; Ziogos 2010). Three studies had adequate sequence generation but allocation concealment was unclear (Faro 1990; Graham 1993; Kamilya 2012; ). The remainder were unclear on both sequence generation and allocation concealment (Figure 1).

For this comparison we have pooled any cephalosporin or any penicillin, at any dose or doses and by any route of administration. Different cephalosporins, different penicillins and different doses will be assessed in other reviews on Different regimens of penicillin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section and Different regimens of cephalosporin antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section.

Subgroup 1: A single cephalosporin (B) versus a single penicillin (A)

Of the included studies with data, 13 assessed a single cephalosporin versus a single penicillin and involved 4010 women (Beningo 1986; Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Lehapa 1999; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Mivumbi 2014; Ng 1992; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1986; Spinnato 2000).

The quality of these studies was generally unclear on selection bias. Three studies were assessed at low risk of bias for both sequence generation and allocation concealment (Beningo 1986; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014). One study had adequate sequence generation but allocation concealment was unclear (Faro 1990).

Primary outcomes

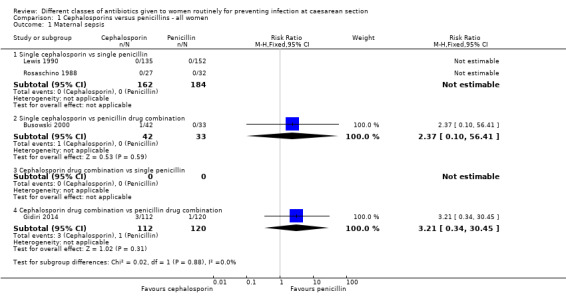

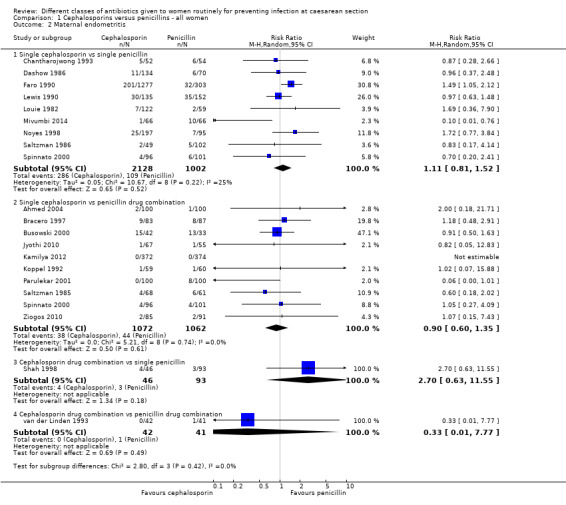

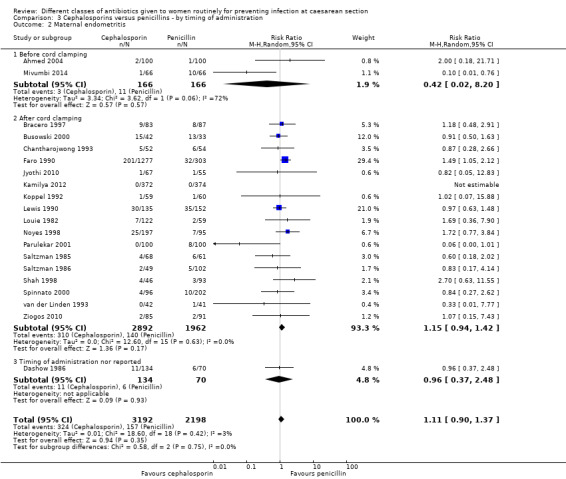

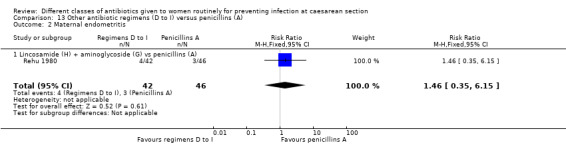

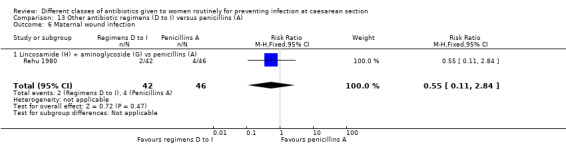

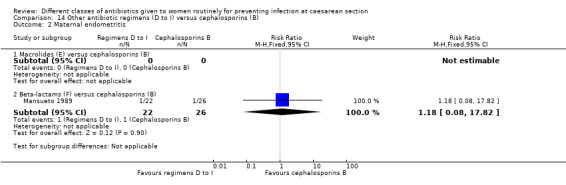

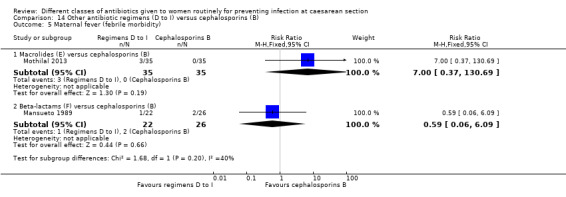

There was no maternal sepsis identified in the 346 women involved in two studies which looked at this outcome (Analysis 1.1). There was no significant difference identified in the incidence of endometritis between cephalosporins and penicillins, average risk ratio (RR) 1.11, and 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81 to 1.52, nine studies, 3130 women, random effects (Tau² = 0.05; Chi² = 10.67, P = 0.22; I² = 25%, Analysis 1.2).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 1 Maternal sepsis.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

None of the included studies assessed either infant sepsis or infant oral thrush.

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified for the following:

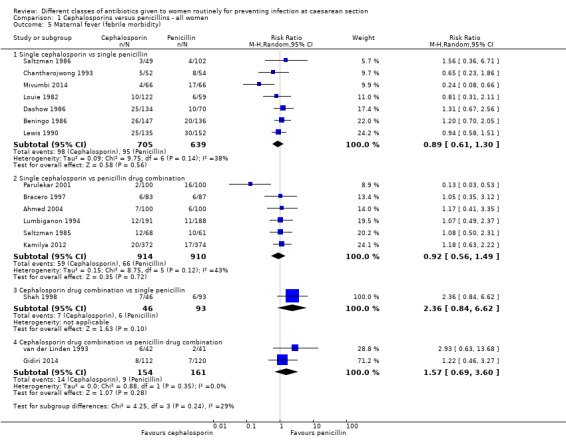

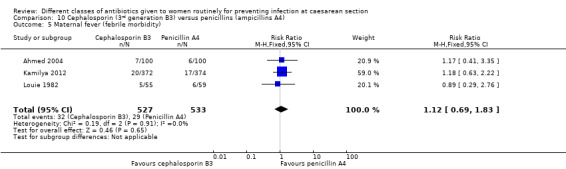

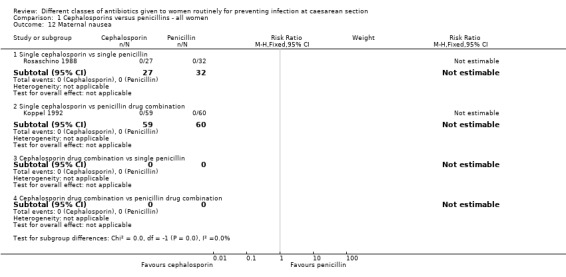

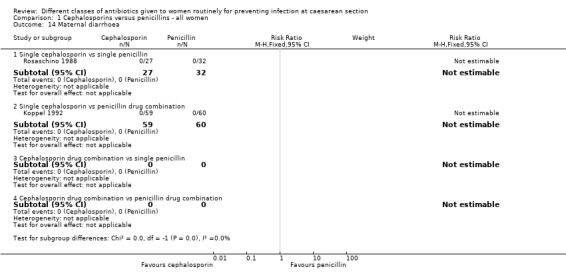

maternal fever (average RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.30, seven studies, 1344 women, random effects Tau² = 0.09; Chi² = 9.75, P = 0.14; I² = 38%, Analysis 1.5);

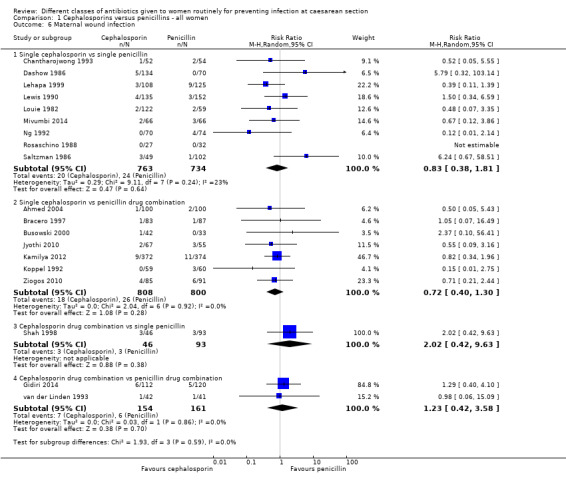

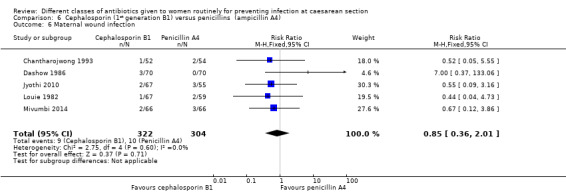

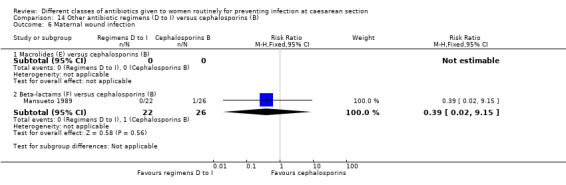

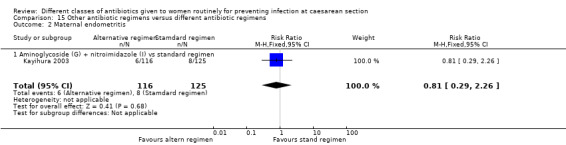

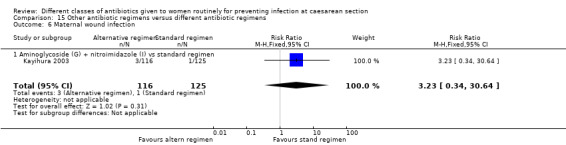

maternal wound infection (average RR 0.83 95% CI 0.38 to 1.81, nine studies, 1497 women, random effects (Tau² = 0.29; Chi² = 9.11, P = 0.24; I² = 23%, Analysis 1.6) ;

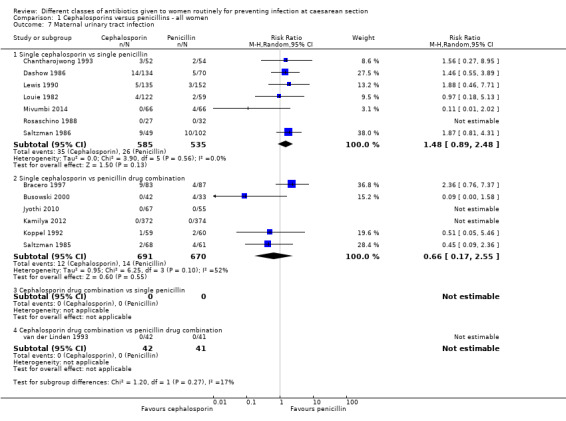

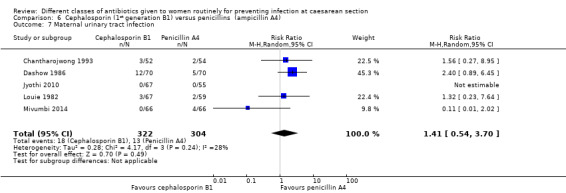

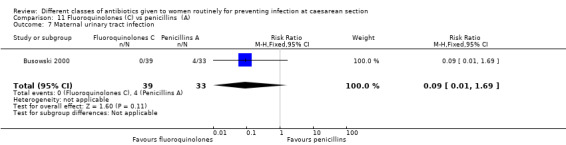

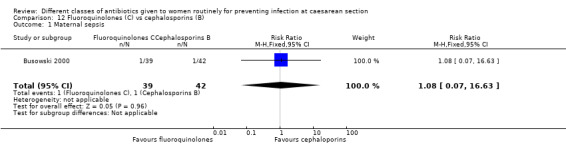

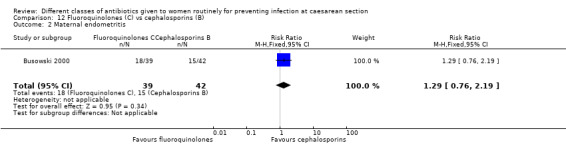

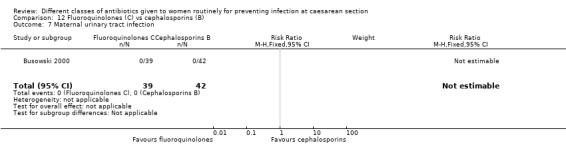

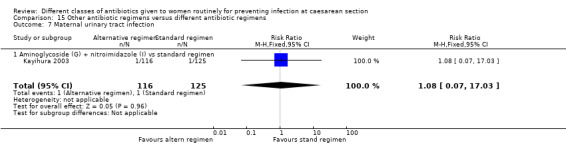

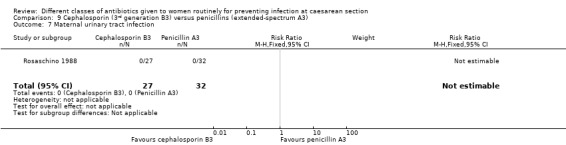

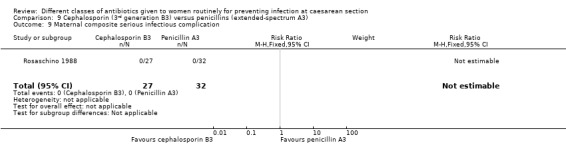

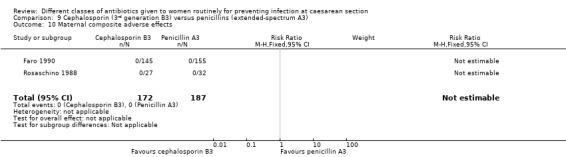

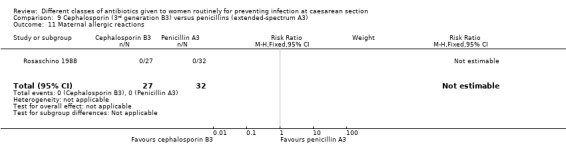

maternal urinary tract infection (average RR 1.48; 95% CI 0.89 to 2.48, seven studies, 1120 women, random effects (Tau² = 0.00; Chi² = 3.90, P = 0.56, I² = 0%, Analysis 1.7);

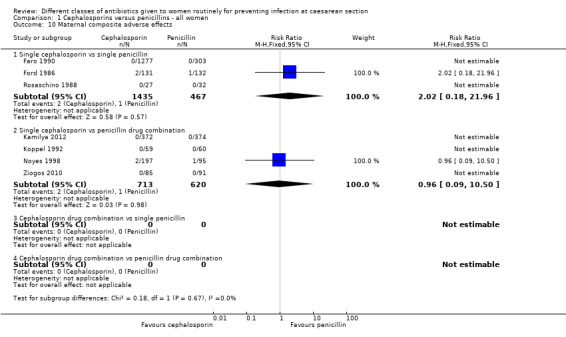

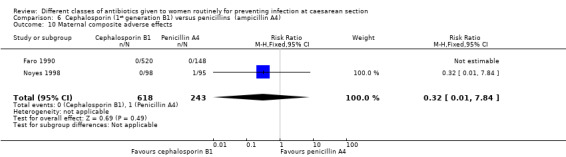

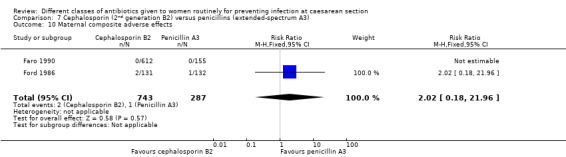

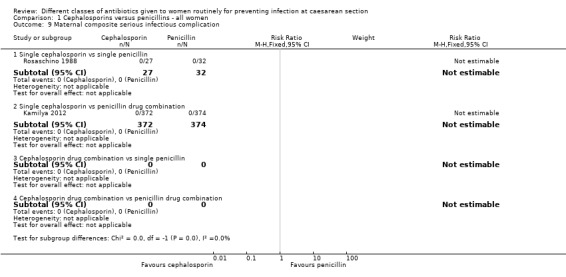

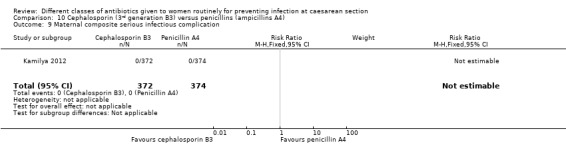

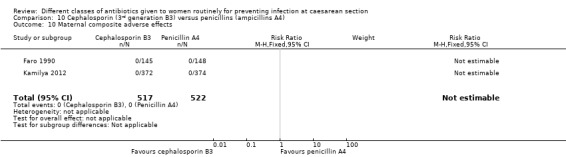

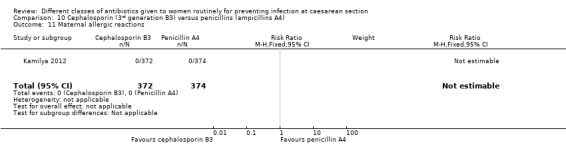

maternal composite adverse effects (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.18 to 21.96, three studies, 1902 women, Analysis 1.10);

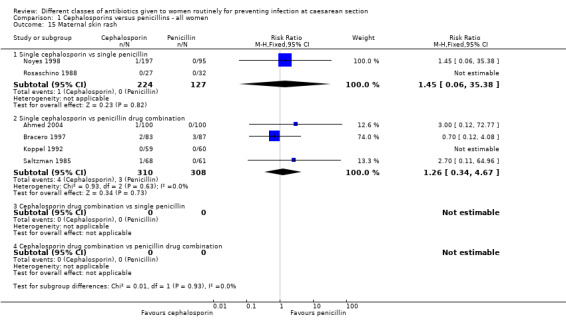

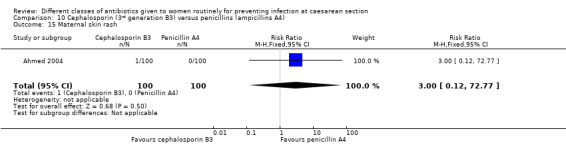

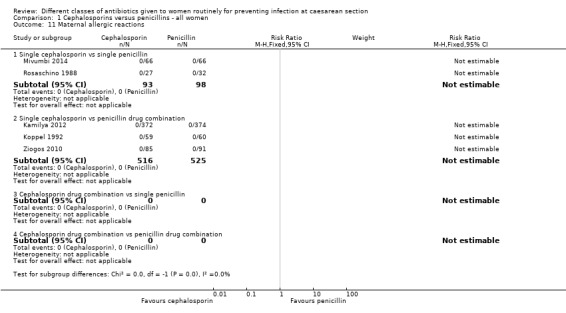

maternal skin rash (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.06 to 35.38, two studies, 351 women, Analysis 1.15).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 6 Maternal wound infection.

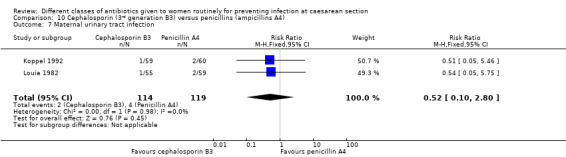

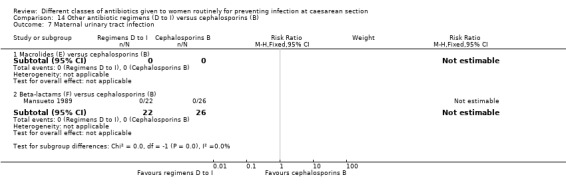

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 7 Maternal urinary tract infection.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 10 Maternal composite adverse effects.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 15 Maternal skin rash.

For the remaining outcomes, either there were no events or the studies did not asses the outcomes.

See Analysis 1.1 to Analysis 1.28.

Subgroup 2: A single cephalosporin (B) versus a penicillin combination (A+)

Twelve studies involving 2875 women compared a single cephalosporin with a penicillin combination. Six studies compared a cephalosporin alone with co‐amoxyclav (Ahmed 2004; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lumbiganon 1994; Saltzman 1985); five studies compared a cephalosporin alone with a penicillin plus sulbactam (Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Noyes 1998; Spinnato 2000; Ziogos 2010). One study compared a cephalosporin alone with a cocktail of drugs including a penicillin (Parulekar 2001).

The quality of these studies was generally unclear. The studies were all unclear for sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Primary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified between single cephalosporins and penicillin combinations in sepsis (RR 2.37, 95% CI 0.10 to 56.41, one study, 75 women, Analysis 1.1), nor in endometritis (average RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.35, ten studies, 2134 women, random effects Tau² = 0.00, Chi² = 5.21, P = 0.74, I² = 0%, Analysis 1.2).

None of the studies assessed infant sepsis or infant oral thrush.

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified between single cephalosporins and penicillin combinations for:

maternal fever (average RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.49, six studies, 1824 women, random effects, Tau² = 0.15; Chi² = 8.75, P = 0.12; I² = 43%, Analysis 1.5);

maternal wound infection (average RR 0.72, (95% CI 0.40 to 1,30, seven studies, 1608 women, random effects Tau² = 0.00; Chi² = 2.04, P = 0.92; I² = 0%, Analysis 1.6);

maternal urinary tract infection (average RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.17 to 2.55, six studies, 1361 women, random effects Tau² = 0.95, Chi² = 6.25, P= 0.10; I² = 52%, Analysis 1.7);

maternal composite adverse effects (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.09 to 10.50, four studies, 1333 women, Analysis 1.10);

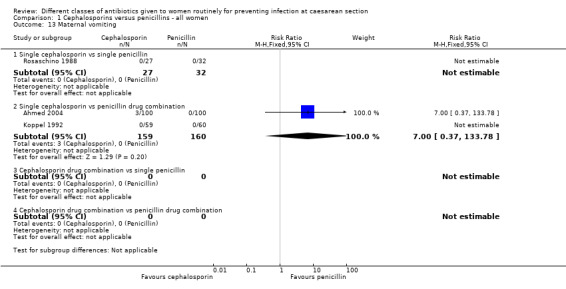

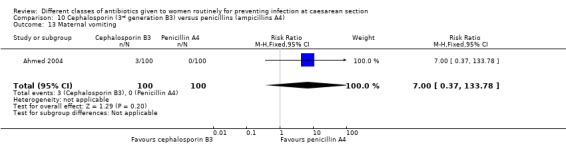

maternal vomiting (RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.37 to 133.78, two studies, 319 women, Analysis 1.13);

maternal skin rash (RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.67, four studies, 618 women, Analysis 1.15).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, Outcome 13 Maternal vomiting.

For the remaining outcomes, either there were no events or the studies did not asses the outcomes.

See Analysis 1.1 to Analysis 1.28.

Subgroup 3: A cephalosporin combination (B+) versus a single penicillin (A)

One study with 147 women compared a cephalosporin combination versus a single penicillin (Shah 1998).

The study was unclear about how the randomisation sequence was generated but was considered at low risk of bias for allocation concealment.

Primary outcomes

We found no significant difference between cephalosporin combination and single penicillins for maternal endometritis (RR 2.70, 95% CI 0.63 to 11.55, one study, 139 women, Analysis 1.2).

The study did not assess maternal sepsis, infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified between cephalosporin combination and single penicillins for:

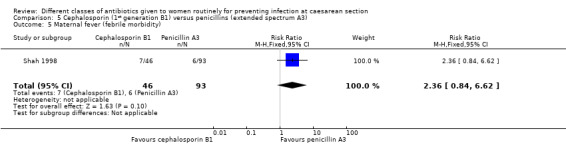

maternal fever (RR 2.36, 95% CI 0.84 to 6.62, one study, 139 women, Analysis 1.5);

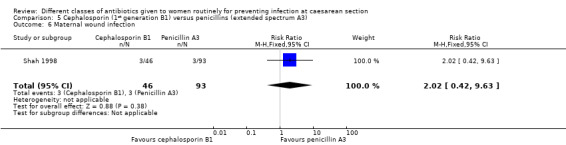

maternal wound infection (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.42 to 9.63, one study, 139 women, Analysis 1.6).

For the remaining outcomes, either there were no events or the study did not assess the outcomes.

See Analysis 1.1 to Analysis 1.26.

Subgroup 4: A cephalosporin combination (B+) versus a penicillin combination (A+)

Two studies with 363 women compared a cephalosporin combination versus a penicillin combination (Gidiri 2014; van der Linden 1993).

In terms of quality, one study was generally unclear for most of the aspects of assessment of bias of these studies (van der Linden 1993) the other study was unclear on sequence generation and allocation concealment and was considered at high risk of bias for blinding (Gidiri 2014).

Primary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified between cephalosporins combinations and penicillins combinations for maternal sepsis (RR 3.21, 95% CI 0.34 to 30.45, one study, 232 women, Analysis 1.1) or endometritis (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.77, one study, 83 women, Analysis 1.2).

The study did not assess infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified between cephalosporins combinations and penicillins combinations for:

maternal fever (RR 1.57, 95% CI 0.69 to 3.60, two studies, 315 women, Analysis 1.5);

maternal wound infection (RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.42 to 3.58, two studies, 315 women, Analysis 1.6).

For the remaining outcomes, either there were no events or the study did not assess the outcomes.

See Analysis 1.1 to Analysis 1.28.

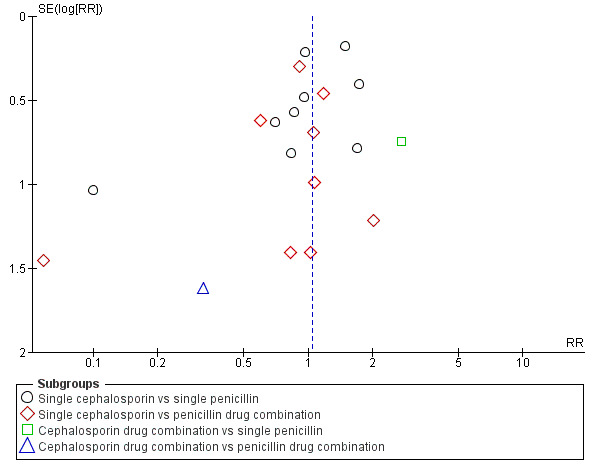

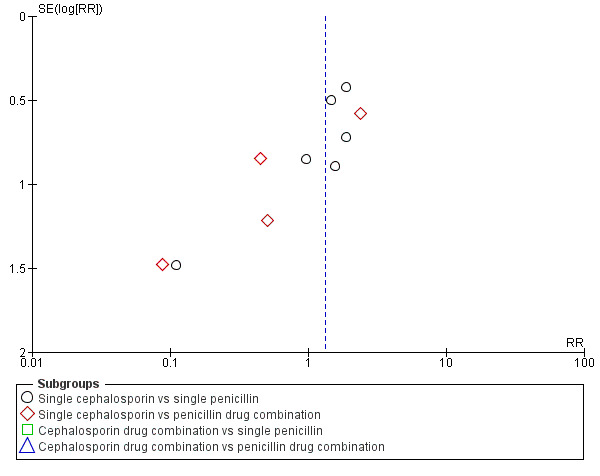

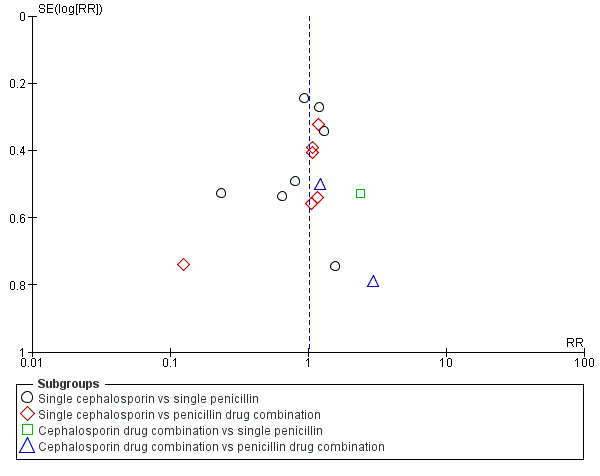

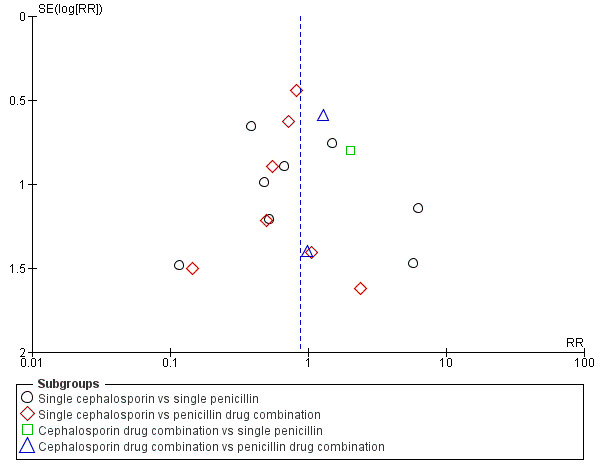

Publication bias

We identified possible publication bias in the assessment of maternal endometritis (Figure 2) and urinary tract infection (Figure 3). However, there appeared to be no publication bias for maternal fever (Figure 4) nor wound infections (Figure 5). However, as we found no overall difference this is probably of little significance.

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, outcome: 1.2 Maternal endometritis.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, outcome: 1.7 Maternal urinary tract infection.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, outcome: 1.5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ all women, outcome: 1.6 Maternal wound infection.

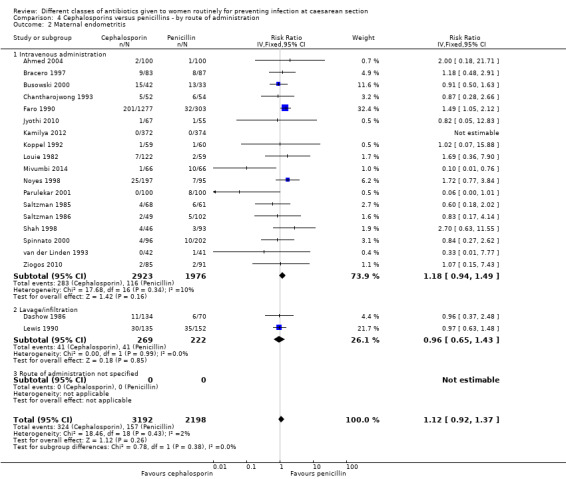

2. Cephalosporins (B) versus penicillins (A) ‐ comparison by type of caesarean section, 22 studies, 5788 women

Twenty‐two studies provided data on at least one primary outcome for this subgroup comparison (seeCharacteristics of included studies. Three studies included women having an elective caesarean section (Ahmed 2004; Jyothi 2010; Shah 1998), five studies included women having a non‐elective caesarean section (Busowski 2000; Faro 1990; Louie 1982; Saltzman 1986; van der Linden 1993) and 14 studies included women having elective or non‐elective caesarean section or the studies did not specify the type of caesarean section (Bracero 1997; Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Gidiri 2014; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lewis 1990; Mivumbi 2014; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Spinnato 2000; Ziogos 2010). A further five studies specified the type of caesarean section but did not provide data on at least one primary outcome (Beningo 1986; Ford 1986; Lehapa 1999; Lumbiganon 1994; Ng 1992).

Four studies were assessed as having low risk of bias in terms of adequate sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment (Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014; Ziogos 2010). Two studies had adequate sequence generation (Faro 1990; Kamilya 2012 ) but unclear allocation concealment;. The remainder of the studies were unclear for both sequence generation and allocation concealment (Figure 1).

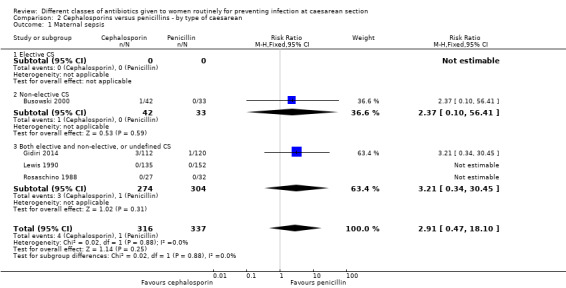

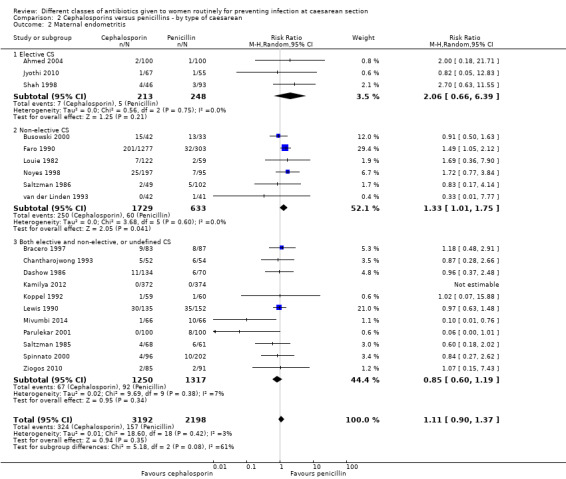

We identified no real differences between the two groups of drugs in relation to the different types of caesarean section for maternal sepsis (RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.47 to 18.10, four studies, 653 women, Analysis 2.1) or endometritis (average RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.37, 20 studies, 5390 women, random effects Tau² = 0.01, Chi² = 18.60, P = 0.42, I² = 3%, Analysis 2.2). However, in the subgroup analysis for endometritis we found differences between groups of type of caesarean section (interaction test, Chi² = 5.18, P = 0.08, I² = 61.4%). Penicillins were more effective than cephalosporins for reducing endometritis among women undergoing non‐elective caesarean section (average RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.75, 6 studies, 2362 women, random effects Tau² = 0.00, Chi² = 3.68, P = 0.60, I² = 0%, Analysis 2.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by type of caesarean, Outcome 1 Maternal sepsis.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by type of caesarean, Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

None of the studies assessed infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

3. Cephalosporins (B) versus penicillins (A) ‐ comparison by timing of administration, 22 studies, 5788 women

Twenty‐two studies provided data on at least one primary outcome for inclusion in this subgroup comparison (seeCharacteristics of included studies). Two studies administered antibiotics before cord clamping (Ahmed 2004; Mivumbi 2014 ) and 19 studies administered the antibiotics after cord clamping (Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Faro 1990; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Lewis 1990; Louie 1982; Mivumbi 2014; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010) and two studies did not report the timing of administration with relation to cord clamping (Dashow 1986; Gidiri 2014). A further five studies addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (Beningo 1986; Ford 1986; Lehapa 1999; Lumbiganon 1994; Ng 1992).

Four studies were assessed as having low risk of bias in terms of adequate sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment (Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014; Ziogos 2010). Two studies had adequate sequence generation but unclear allocation concealment (Faro 1990; Kamilya 2012) The remainder of the studies were unclear for both sequence generation and allocation concealment (Figure 1).

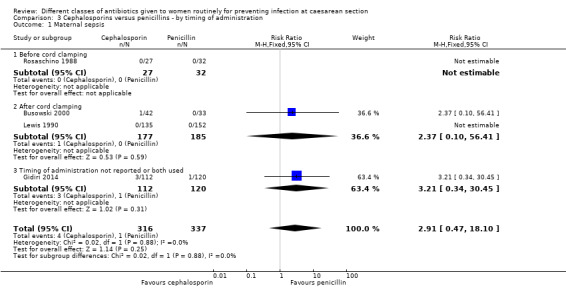

We identified no real differences between the two groups of drugs for maternal sepsis (RR 2.91, 95% CI 0.47 to 18.10, four studies, 653 women, Analysis 3.1) or endometritis (average RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.37, 20 studies, 5390 women, random effects Tau² = 0.01, Chi² = 18.6, P = 0.42, I² = 3%, Analysis 3.2) in relation to the timing of administration. A separate review will be undertaken where studies have compared directly the antibiotic being given before versus after cord clamping ('Timing of prophylactic antibiotics for preventing infectious morbidity in women undergoing caesarean section').

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by timing of administration, Outcome 1 Maternal sepsis.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by timing of administration, Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

The interaction test for endometritis showed no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.75) and this was also the case visually.

None of the studies assessed infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

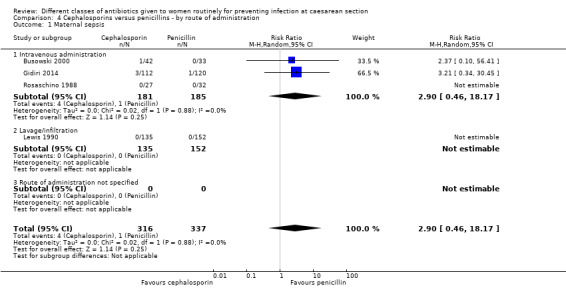

4. Cephalosporins (B) versus penicillins (A) ‐ comparison by route of administration, 22 studies, 5788 women

Twenty‐two studies provided data on at least one primary outcome for inclusion in this subgroup comparison. Twenty studies compared the antibiotics when given by intravenous administration (Ahmed 2004; Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Chantharojwong 1993; Faro 1990; Gidiri 2014; Jyothi 2010; Kamilya 2012; Koppel 1992; Louie 1982; Mivumbi 2014; Noyes 1998; Parulekar 2001; Rosaschino 1988; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986; Shah 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010). Two studies compared the antibiotics when administered as a lavage/irrigation (Dashow 1986; Lewis 1990). A further five studies addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (Beningo 1986; Ford 1986; Lehapa 1999; Lumbiganon 1994; Ng 1992).

Four studies were assessed as having low risk of bias in terms of adequate sequence generation and adequate allocation concealment (Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014; Ziogos 2010). Two studies had adequate sequence generation but unclear allocation concealment (Faro 1990; Kamilya 2012). The remainder of the studies were unclear for both sequence generation and allocation concealment (Figure 1).

We identified no real differences between the two groups of drugs for maternal sepsis (average RR 2.90, 95% CI 0.46 to 18.17, four studies, 653 women, random effects Tau² = 0.00, Chi² = 0.02, P = 0.88, I² = 0%, Analysis 4.1) or endometritis (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.37, 20 studies, 5390 women, Analysis 4.2) in relation to the route of administration. A separate review will be undertaken where studies have compared directly the different routes of antibiotic administration ('Routes of administration for antibiotic given to women routinely for preventing infection after caesarean section').

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by route of administration, Outcome 1 Maternal sepsis.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Cephalosporins versus penicillins ‐ by route of administration, Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

The interaction test for endometritis showed no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.38) and this was also the case visually.

None of the studies assessed infant sepsis nor infant oral thrush.

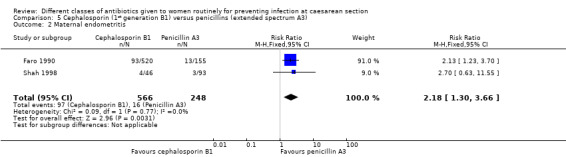

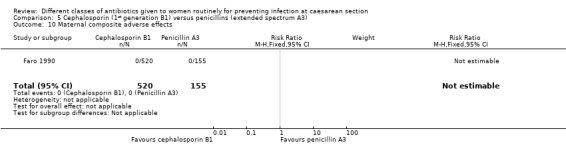

5. First generation cephalosporins (B1) versus extended spectrum penicillins (A3) ‐ all women, two studies, 822 women

Two studies provided data for inclusion in this comparison (Faro 1990; Shah 1998). Cephalosporins included cefazolin (Faro 1990), cephazoline, (Faro 1990) and cephradine plus metronidazole (Shah 1998). Penicillins included only piperacillin (Faro 1990; Shah 1998). Both studies were of unclear quality, with one being unclear about the sequence generation (Shah 1998) and the other being unclear about concealment allocation (Faro 1990). (Figure 1).

Primary outcomes

There was a significantly higher incidence of maternal endometritis with first generation cephalosporins compared with extended spectrum penicillins (RR 2.18, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.66, two studies, 814 women, Analysis 5.2). None of the other primary outcomes (maternal sepsis, infant sepsis and infant thrush) were assessed in either of these studies.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (extended spectrum A3), Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

Secondary outcomes

There was no statistically significant difference identified in maternal fever (RR 2.36, 95% CI 0.84 to 6.62, one study, 139 women, Analysis 5.5) nor maternal wound infection (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.42 to 9.63, one study, 139 women, Analysis 5.6). None of the other secondary outcomes were assessed in this comparisons.

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (extended spectrum A3), Outcome 5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (extended spectrum A3), Outcome 6 Maternal wound infection.

Neither study assessed any outcomes on the infant, nor post‐discharge infections or readmissions for the mother.

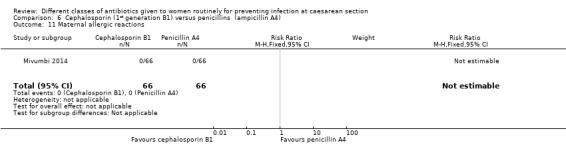

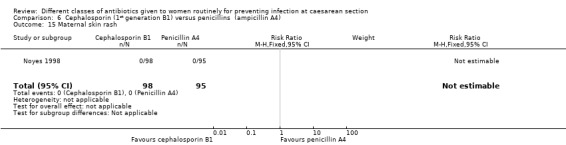

6. First generation cephalosporins (B1) versus aminopenicillins (A4) ‐ all women, eight studies, 1882 women

Eight studies provided data for inclusion in this comparison (Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Jyothi 2010; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Mivumbi 2014; Noyes 1998). Cephalosporins included cefazolin (Chantharojwong 1993; Faro 1990; Jyothi 2010; Louie 1982; Lumbiganon 1994; Noyes 1998; Mivumbi 2014) and cephapirin (Dashow 1986). Penicillins included ampicillin (Chantharojwong 1993; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Louie 1982; Mivumbi 2014), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (Lumbiganon 1994) and ampicillin/sulbactam (Noyes 1998). A further study addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (Graham 1993). Two studies were assessed as adequate on sequence generation and allocation concealment (Dashow 1986; Mivumbi 2014) and one study was adequate on allocation concealment but because sequence generation was unclear overall uncertainty remains (Lumbiganon 1994). The remainder were assessed as unclear for allocation concealment (Figure 1).

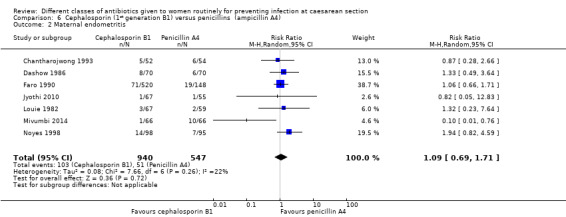

Primary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified in maternal endometritis (average RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.71, seven studies, 1487 women, random effects, Tau² = 0.08, Chi² = 7.66, P = 0.26, I² = 22%, Analysis 6.2). None of the other primary outcomes (maternal sepsis, infant sepsis and infant thrush) were assessed in any of these studies.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

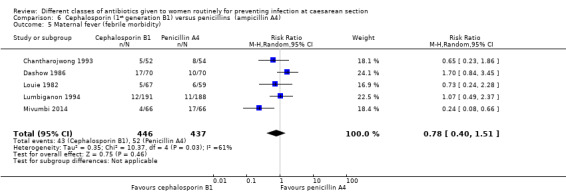

Secondary outcomes

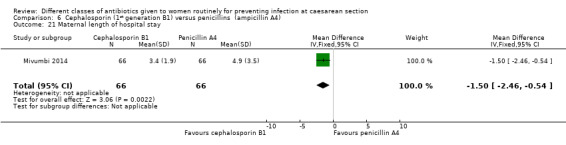

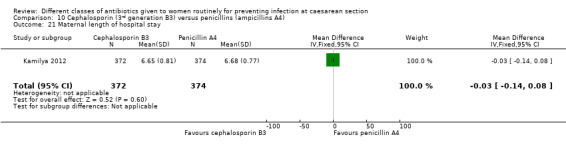

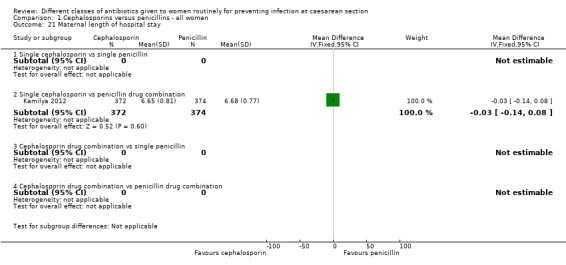

There was no statistically significant difference identified in maternal fever (average RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.51, five studies, 883 women, random effects Tau² = 0.35, Chi² = 10.37, P = 0.03, I² = 61%, Analysis 6.5), wound infection (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.01, five studies, 626 women, Analysis 6.6), urinary tract infections (average RR 1.41, 95% CI 0.54 to 3.70, five studies, 626 women, random effects Tau² = 0.28, Chi² = 4.17, P = 0.24, I² = 28%, Analysis 6.7), nor maternal composite adverse outcomes (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.01 to 7.84, two studies, 861 women, Analysis 6.10). There was a significant reduction in the mothers' hospital stay with the cephalosporins (mean difference (MD) ‐1.50, 95% CI ‐2.46 to ‐0.54, one study, 132 women, Analysis 6.21). There were no events in the assessments of maternal allergic reactions not skin rashes. None of the other secondary outcomes were assessed in any of the studies.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 6 Maternal wound infection.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 7 Maternal urinary tract infection.

6.10. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 10 Maternal composite adverse effects.

6.21. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Cephalosporin (1st generation B1) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 21 Maternal length of hospital stay.

None of the studies assessed any outcomes on the infant, nor post‐discharge infections or readmissions for the mother.

7. Second generation cephalosporins (B2) versus extended spectrum penicillins (A3) ‐ all women, six studies, 2077 women

Six studies provided data for inclusion in this comparison (Beningo 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Lewis 1990; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986). Cephalosporins included cefoxitin (Beningo 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986; Lewis 1990; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986), cefonicid (Faro 1990) and cefotetan (Faro 1990). Penicillins included piperacillin (Beningo 1986; Faro 1990; Ford 1986), ticarcillin (Lewis 1990; Saltzman 1985) and mezlocillin (Saltzman 1986). A further study addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (De‐Lalla 1988). Only one study was assessed as adequate on sequence generation and allocation concealment (Beningo 1986). One study was adequate for sequence generation but unclear on allocation concealment (Faro 1990) and the remainder were unclear on both criteria (Figure 1).

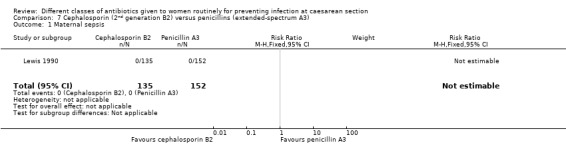

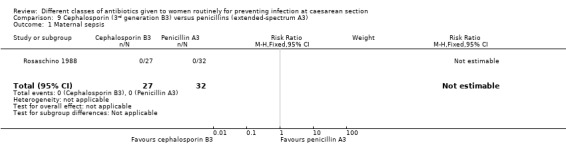

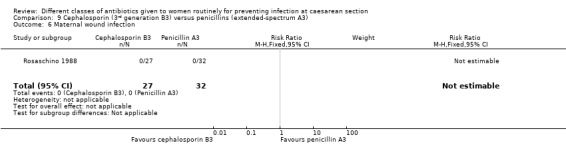

Primary outcomes

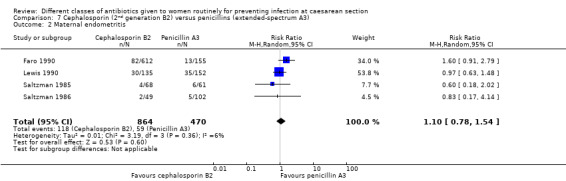

There was no sepsis in the 287 women included in the one study that reported it (Lewis 1990). We found no significant difference identified for maternal endometritis (average RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.54, four studies, 1334 women, random effects Tau² = 0.01, Chi² = 3.19, P = 0.36, I² = 6%, Analysis 7.2). None of the other primary outcomes (infant sepsis and infant thrush) were assessed in either of these studies.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

Secondary outcomes

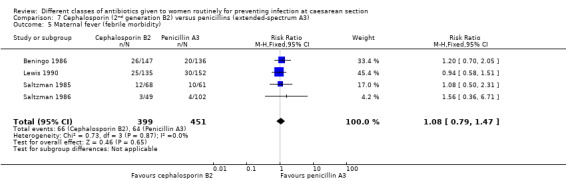

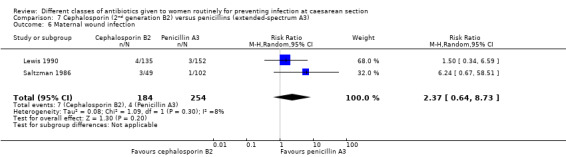

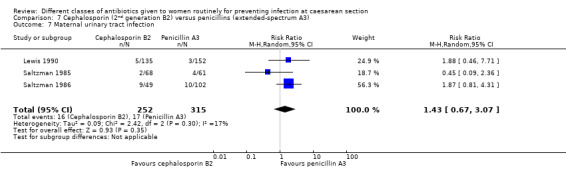

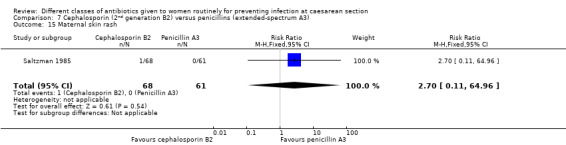

There was no significant difference identified for maternal fever (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.47, four studies, 850 women, Analysis 7.5), wound infection (average RR 2.37, 95% CI 0.64 to 8.73, two studies, 438 women, random effects Tau² = 0.08, Chi² = 2.37, P = 0.30, I² = 8%, Analysis 7.6), urinary tract infection (average RR 1.43, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.07, three studies, 567 women, random effects Tau² = 0.09, Chi² = 2.42, P = 0.30, I² = 17%, Analysis 7.7), maternal composite adverse effects (RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.18 to 21.96, two studies, 1030 women, Analysis 7.10) and skin rash (RR 2.70, 95% CI 0.11 to 64.96, one study, 129 women, Analysis 7.15).

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 6 Maternal wound infection.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 7 Maternal urinary tract infection.

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 10 Maternal composite adverse effects.

7.15. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (extended‐spectrum A3), Outcome 15 Maternal skin rash.

Three studies looked at infection rates after discharge (Beningo 1986; Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986). Two other studies reported no infections up to six weeks postoperatively based on 305 women participating in the studies (Saltzman 1985; Saltzman 1986).

None of the studies assessed any outcomes on the infant.

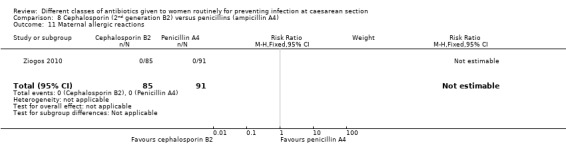

8. Second generation cephalosporins (B2) versus aminopenicillins (A4) ‐ all women, eight studies, 1921 women

Eight studies provided data for inclusion in this comparison (Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Noyes 1998; Spinnato 2000; van der Linden 1993; Ziogos 2010). Cephalosporins included cefotetan (Bracero 1997; Busowski 2000; Faro 1990; Noyes 1998; Spinnato 2000; Ziogos 2010), cefamandole (Dashow 1986), cefonicid (Faro 1990), cefoxitin (Faro 1990) and cefuroxime (van der Linden 1993). Penicillins included ampicillin (Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986; Faro 1990; Spinnato 2000), ampicillin/sulbactam (Busowski 2000; Noyes 1998; Spinnato 2000) and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (van der Linden 1993). A further study addressed this comparison but did not provide data in a format suitable for inclusion (Voto 1986). Two studies were assessed as adequate on sequence generation and allocation concealment (Bracero 1997; Dashow 1986). One study was assessed as adequate on sequence generation but unclear on allocation concealment (Faro 1990) and the remainder were unclear on both criteria (Figure 1).

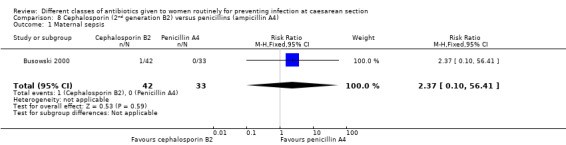

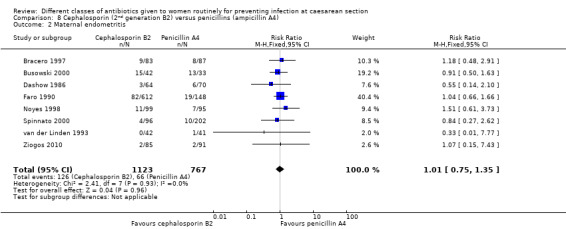

Primary outcomes

There was no significant difference identified in maternal sepsis (RR 2.37, 95% CI 0.10 to 56.41, one study, 75 women, Analysis 8.1) nor endometritis (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.35, eight studies, 1890 women, Analysis 8.2). None of the other primary outcomes (infant sepsis and infant thrush) were assessed in any of these studies.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 1 Maternal sepsis.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 2 Maternal endometritis.

Secondary outcomes

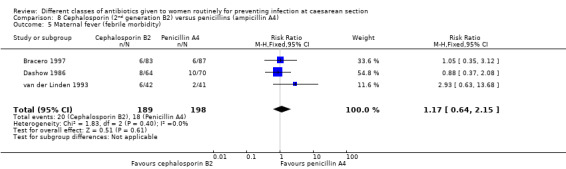

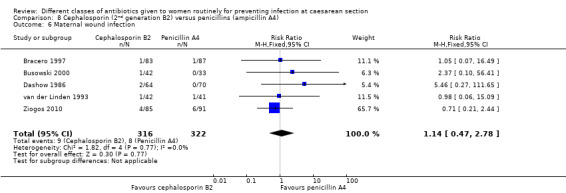

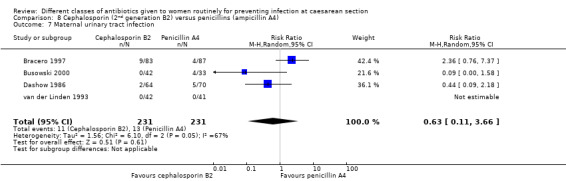

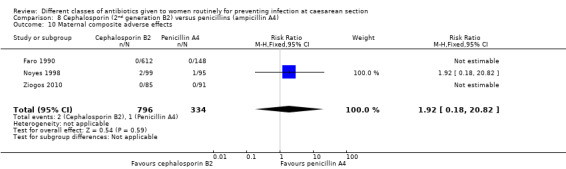

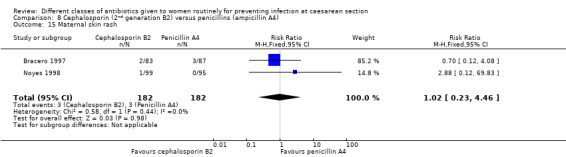

There was no significant difference identified for maternal fever (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.64 to 2.15, three studies, 387 women, Analysis 8.5), wound infection (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.78, five studies, 638 women, Analysis 8.6), urinary tract infection (average RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.66, four studies, 462 women, random effects Tau² = 1.56, Chi² = 6.10; P = 0.05, I² = 67%, Analysis 8.7), maternal composite adverse effects (RR 1.92, 95% CI 0.18 to 20.82, three studies, 1130 women, Analysis 8.10), nor skin rash (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.23 to 4.46, two studies, 364 women, Analysis 8.15). For urinary tract infection there was high heterogeneity and studies showed effects in different directions but no overall difference was identified Analysis 8.7). None of the other secondary outcomes were assessed in any of the included studies.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 5 Maternal fever (febrile morbidity).

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 6 Maternal wound infection.

8.7. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 7 Maternal urinary tract infection.

8.10. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 10 Maternal composite adverse effects.

8.15. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Cephalosporin (2nd generation B2) versus penicillins (ampicillin A4), Outcome 15 Maternal skin rash.

None of the studies assessed any outcomes on the infants, nor post‐discharge infections or readmissions for the mother.

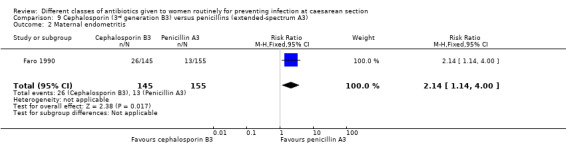

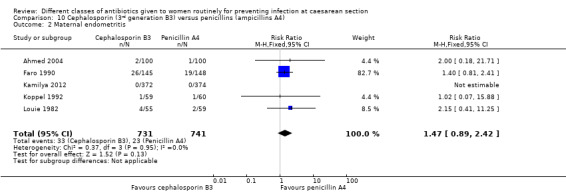

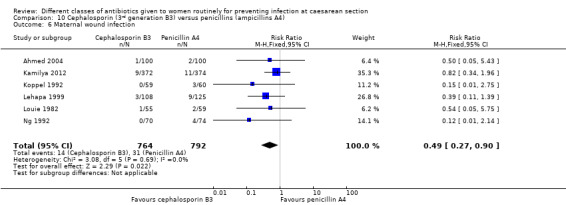

9. Third generation cephalosporins (B3) versus extended‐spectrum penicillins ( A3) ‐ all women, two studies, 359 women