As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues advancing globally, reporting of clinical outcomes and risk factors for intensive care unit admission and mortality are emerging. Early Chinese and Italian reports associated increasing age, male sex, smoking, and cardiometabolic comorbidity with adverse outcomes.1 Striking differences between Chinese and Italian mortality indicate ethnicity might affect disease outcome, but there is little to no data to support or refute this.

Ethnicity is a complex entity composed of genetic make-up, social constructs, cultural identity, and behavioural patterns.2 Ethnic classification systems have limitations but have been used to explore genetic and other population differences. Individuals from different ethnic backgrounds vary in behaviours, comorbidities, immune profiles, and risk of infection, as exemplified by the increased morbidity and mortality in black and minority ethnic (BME) communities in previous pandemics.3

As COVID-19 spreads to areas with large cosmopolitan populations, understanding how ethnicity affects COVID-19 outcomes is essential. We therefore reviewed published papers and national surveillance reports on notifications and outcomes of COVID-19 to ascertain ethnicity data reporting patterns, associations, and outcomes.

Only two (7%) of 29 publications reported ethnicity disaggregated data (both were case series without outcomes specific to ethnicity). We found that none of the ten highest COVID-19 case-notifying countries reported data related to ethnicity; UK mortality reporting, for example, does not require information on ethnicity. This omission seems stark given the disproportionate number of deaths among health-care workers from BME backgrounds.4, 5 Recent UK data from intensive care units indicate that over a third of patients are from BME backgrounds.6

Given previous pandemic experience, it is imperative that policy makers urgently ensure ethnicity forms part of a minimum dataset. More importantly, ethnicity-disaggregated data must occur to permit identification of potential outcome risk factors through adjustment for recognised confounders.

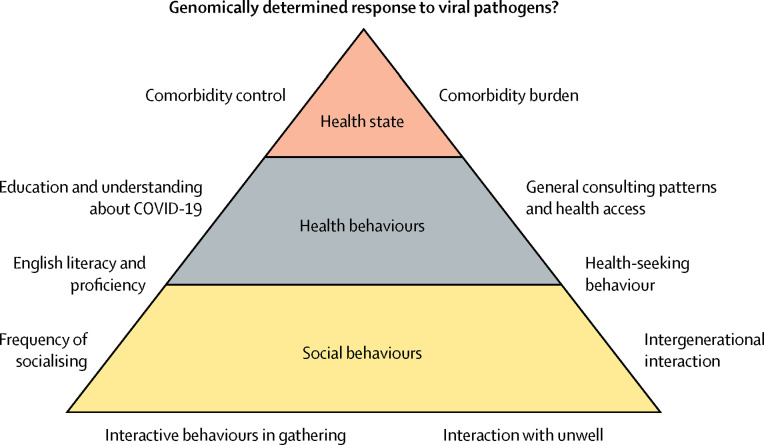

BME communities might be at increased risk of acquisition, disease severity, and poor outcomes in COVID-19 for several reasons (figure ). Specific ethnic groups, such as south Asians, have higher rates of some comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases, which have been associated with severe disease and mortality in COVID-19.7 Ethnicity could interplay with virus spread through cultural, behavioural, and societal differences including lower socioeconomic status, health-seeking behaviour, and intergenerational cohabitation. Disentangling the relative importance of these factors requires both prospective studies, focusing on quantifying absolute risks and outcomes, and qualitative studies of behaviours and responses to pandemic control messages.

Figure.

The potential interaction of ethnicity related factors on SARS-CoV-2 infection likelihood and COVID-19 outcomes

COVID-19=coronavirus disease 2019. SARS-CoV-2=severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

If ethnicity is found to be associated with adverse COVID-19 outcomes, this must directly, and urgently, inform public health interventions globally.

Acknowledgments

MP received grants and personal fees from Gilead Sciences outside of this Correspondence. JSM received grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during this work. WH is Trustee of the South Asian Health Foundation. KK is Director of the Black and Minority Ethnic Centre, NIHR Applied Research Collaborations (ARC) East Midlands. All other authors have nothing to declare. MP and JSM are supported by the NIHR. The views expressed in this Correspondence are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health. KK and MP acknowledge the NIHR ARC—East Midlands, the NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, and the Centre for Black Minority Ethnic Health. DP and SS are supported by NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowships.

References

- 1.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C. “Race” and “ethnicity” in biomedical research: How do scientists construct and explain differences in health? Soc Sci Med. 2008;68:1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao H, Harris RJ, Ellis J, Pebody RG. Ethnicity, deprivation and mortality due to 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) in England during the 2009/2010 pandemic and the first post-pandemic season. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:3375–3383. doi: 10.1017/S0950268815000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddique H. UK government urged to investigate coronavirus deaths of BAME doctors. April 10, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/apr/10/uk-coronavirus-deaths-bame-doctors-bma

- 5.Croxford R. Coronavirus cases to be tracked by ethnicity. April 18, 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-52338101

- 6.Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre . Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre; London: 2020. ICNARC COVID-19 study case mix programme. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tillin T, Hughes AD, Mayet J. The relationship between metabolic risk factors and incident cardiovascular disease in Europeans, South Asians, and African Caribbeans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1777–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]