Abstract

Objective

Clinical trials of children’s drugs are of great significance to rational drug use in children. However, paediatric drugs trials in China are facing complex challenges. At present, the investigation data on registration status of paediatric drug trials in China are still relatively lacking, and relevant research is urgently needed.

Methods

The advanced retrieval function is used to retrieve clinical trials data in the Clinical Trial.gov and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry databases in 22 April 2019. Fifteen key items were analysed to describe trial characteristics, including: registration number, study start date (year), mode of funding, type of disease, medicine type, research stage, research design, sample size, number of experimental groups, placebo group, blind method, implementation centre, child specific, newborn specific and participant age.

Results

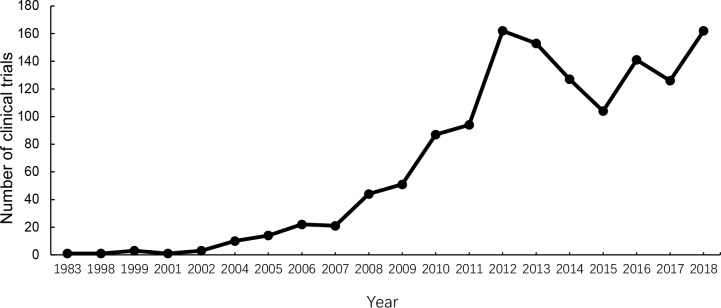

A total of 1388 clinical trials of paediatric drugs conducted in China were registered. The number of paediatric drug trials grew steadily over time, from less than 20 per year before 2005 to more than 100 per year after 2012. Most clinical trials were postmarketing (n=800, 57.6%), single-centre (n=1045, 75.3%), intervention studies (n=1161, 83.6%) without blinded methods (1169, 84.2%) and funded by non-profit organisations (n=838, 60.4%). The number of clinical trials for antineoplastic agents (n=254, 18.3%), anti-infectives (n=156, 11.2%) and vaccines (n=154, 11.1%) is the largest.

Conclusion

Paediatric drug trials in China made a significant progress in recent years. Innovative method and trial design optimisation should be encouraged to accelerate paediatric clinical research. Pharmaceutical companies need to be further stimulated to carry out more high-quality paediatric clinical trials with support of paediatric drug legislation.

Keywords: paediatric practice, evidence based medicine

What is known about the subject?

Clinical trials of children’s drugs are of great significance to rational drug use in children.

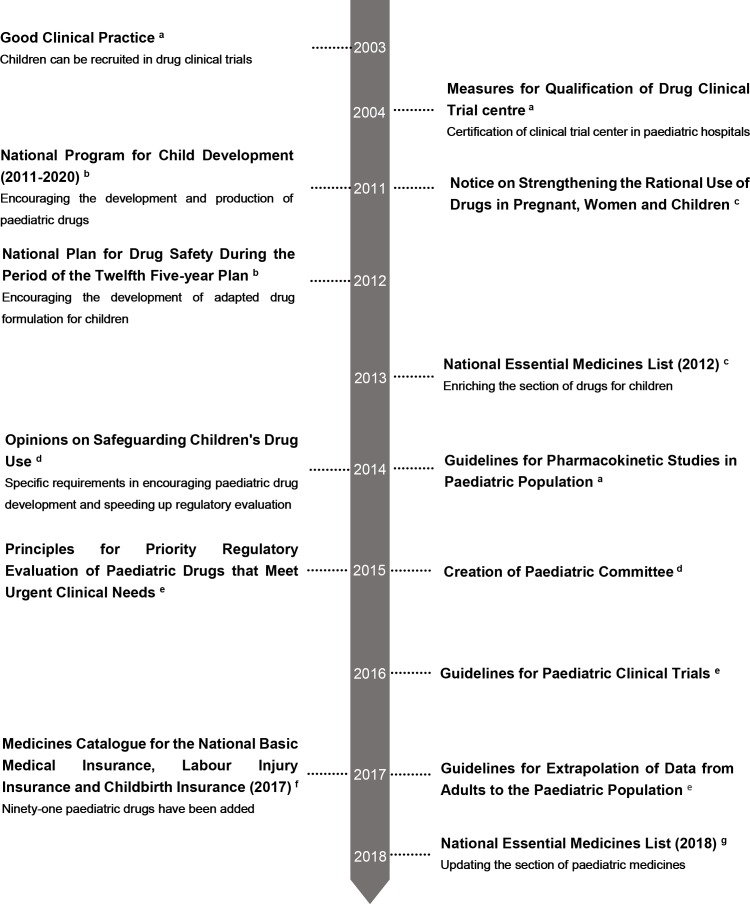

Starting from 2003, children were formally included in the scope of clinical trials in the good clinical practice in China.

What this study adds?

Paediatric drug trials in China made a significant progress in recent years.

Most paediatric drug trials in China were postmarketing, single-centre, intervention studies without blinded methods and funded by non-profit organisations.

The number of paediatric drug trials for antineoplastic agents, antiinfectives and vaccines is the largest in China.

Introduction

The rational use of medicines in children is limited by the absence of scientific evidence and the off-label use of drugs is a critical issue in paediatric clinical practice, so the need for properly designed and conducted paediatric clinical trials has never been greater.1 2 Insufficient paediatric clinical trials increase the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in children.3 Due to the scant information on paediatric prescriptions, clinicians often prescribe unauthorised indications or dosage forms of medicines for children.4 5 ADR monitoring data show that compared with 6.9% in adults, the ADR rate of children in China is 12.9%, of which 24.4% of neonates. According to WHO statistics in 2010, about 7.6 million children under the age of 5 die each year due to the lack of safe and effective drugs. The improper use of paediatric medicines will endanger children’s health, and bring misfortune to families and heavy burden to society.

Clinical trials are the golden standard for evaluating the safety and efficacy of drugs and producing evidence-based medical evidence. Clinical trial registration is to register the important information of the trial in the open clinical trial registration institution at the initial stage of the trial, so as to provide reliable information to the public, health practitioners, researchers and sponsors, and make the design and implementation of the clinical trial transparent. Pretrial registration helps to reduce publication bias, selection bias, improve transparency of trials and make clinical trials conducted under public supervision, which is particularly important for the development of clinical trials for children.6

The paediatric drugs trials in China mainly face two challenges, including the support of adaptive policies and the application of new technologies and methods. The introduction of the Paediatric Regulation by the European Union, together with the renewal of the Paediatric Rule by the US Food and Drug Administration on the requirements for paediatric labelling made it mandatory for sponsors to develop drugs for the paediatric population and promotes the paediatric drug trials in Europe and USA.7 8 However, very little is known about the situation of paediatric drug trials in other countries, particularly in China, home to nearly 300 millions children. In order to support the global research in paediatric drug development and clarify the specific Chinese characteristics of paediatric drugs trials, we analysed the paediatric drug trials registered to be conducted in China.

Methods

Design

We investigate the current status of paediatric clinical trials in China through the advanced retrieval functions of the Clinical Trial.gov (CTg) and Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) databases. The data deadline is 22 April 2019. The key words of the ChiCTR are child, infant, newborn and adolescent (in Chinese). Retrieve CTg qualification is Child (birth-18). The items enrolled into the database include: registration number, study start date (year), mode of funding, type of disease, medicine type, research stage, research design, sample size, number of experimental groups, placebo group, blind method, implementation centre, child specific, newborn specific and participant age.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of our research.

Results

Among all (n=34 574) Chinese clinical trials registered in the CTg and ChiCTR, 3368 trials (9.74%) involved the paediatric population. In CTg, the number of paediatric clinical trials in China was 2526, compared with 24 488 in the USA. A total of 1388 clinical trials (4.01%) were paediatric drug trials, including 466 in ChiCTR and 922 in CTg.

In these paediatric drug trials, 547 trials were designed specifically for children under the age of 18, while the other 841 trials involved both children and adults. There are 148 clinical trials for infants (less than 1 year old), including 36 studies specifically for newborns. A total of 1048 clinical trials involve the age group of adolescents (from 12 to 18 years old), of which about four-fifths included adolescents and adults. The number of registered paediatric drugs trials in China from 1983 to 2018 is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The number of registered paediatric drug trials in China from 1983 to 2018.

Most paediatric drug trials were classified as postmarketing study (n=800, 57.6%), and were funded by non-profit organisations (n=838, 60.4%). The industry sponsored only 437 (31.5%) trials. Around two-thirds (n=924) of trials were randomised and just about one-eighth (n=168) involved a comparison with a placebo. The majority of trials were single-centre studies (n=1045, 75.3%) and without blinded methods (n=1169, 84.2%). The number of interventional studies (1161) far exceeds that of observational studies (227). About two-thirds of clinical trials have a sample size of less than 300. The distribution of sample size is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Sample sizes in paediatric drug trials

| Sample size (participants (n)) | No of paediatric drug trials | Proportion (%) |

| 0–100 | 538 | 38.7 |

| 101–200 | 264 | 19.0 |

| 201–300 | 144 | 10.4 |

| 301–400 | 90 | 6.5 |

| 401–500 | 54 | 3.9 |

| 501–1000 | 139 | 10.0 |

| >1000 | 151 | 10.9 |

| Unknown | 8 | 0.6 |

| Total | 1388 | 100.0 |

The drug classes in 1388 paediatric drug trials are shown in table 2, among which the clinical trials for antineoplastic agents, anti-infectives and vaccines are the most. There were 93 paediatric drug trials including Chinese traditional medicine.

Table 2.

Classes of drugs in paediatric drug trials

| Classes | No of trials | Proportion (%) |

| Antineoplastic agents | 254 | 18.3 |

| Anti-infectives | 156 | 11.2 |

| Vaccines | 154 | 11.1 |

| Anaesthetics and analgesics | 108 | 7.8 |

| Anticoagulants, anticoagulants and haematopoietic agents | 87 | 6.3 |

| Immunosuppressants and glucocorticoids | 81 | 5.8 |

| Asthma drugs | 50 | 3.6 |

| Antihypertensive and cardiotonic drugs | 46 | 3.3 |

| Dermatologicals | 42 | 3.0 |

| Vitamins, electrolyte solutions, nutrition and nutrient supplements | 36 | 2.6 |

| Antiepileptic drugs | 33 | 2.4 |

| Hormonal preparations | 29 | 2.1 |

| Diabetes medication | 28 | 2.0 |

| Antipsychotics | 26 | 1.9 |

| Drugs for pulmonary hypertension | 21 | 1.5 |

| Probiotic preparations | 20 | 1.4 |

| Ophthalmic drugs | 20 | 1.4 |

| Drugs for nerve injury repair and nervous system development | 20 | 1.4 |

| Others | 177 | 12.8 |

| Total | 1388 | 100.0 |

Discussion

In recent years, the Chinese government has adapted drug policy for children and paid considerable attention to the rational use of paediatric drugs and the development of paediatric clinical trials (figure 2). Our results demonstrated for the first time the situation of paediatric drug trials in China. Consistent with the initiatives of promoting paediatric drug development in Europe and USA, the paediatric drug trials in China made a significant progress after 2012.

Figure 2.

Policies on paediatric drug trials in China. (a) State Food and Drug Administration, SFDA (now namely National Medical Products Administration, NMPA); (b) The State Council; (c) Ministry of Health (now namely National Health Commission); (d) National Health and Family Planning Commission, NHFPC (now namely National Health Commission); (e) China Food and Drug Administration, CFDA (now namely NMPA); (f) Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security; (g) National Health Commission.

As reported, there were fewer paediatric randomised drug trials in developing countries than in developed countries in 1996–2002.9 Especially in China, there are few paediatric drug trials. Starting from 2003, children were formally included in the scope of clinical trials in the good clinical practice in China. This means that, like adults, children have the right to obtain evidence-based medical data for safe and effective treatment after clinical trials of new drugs under ethical and strict supervision. The development of paediatric clinical trials is conducive to protect children from invalid interventions. However, the proportion of clinical trials registered for children in China was 9.74% in this study, which was lower than that in Canada (22.4%), the USA (21.1%), the UK (18.5%), Japan (18.4%) and Germany (14.5%).10 Industry-sponsored trials are still limited in China and most of trials were still funded by public finding. This might be one obvious reason for the lack of significant increase in last few years. The adaptive paediatric drug trials legislation is urgently needed in China to stimulate the enthusiasm of pharmaceutical companies.

This study shows that the proportion of observational research and interventional research is about 1:5, which shows that interventional research is more concerned and valued, and the content of observational research in design and implementation is broader and more complex. In our study, the proportion of paediatric drug trials with more than 100 participants and 500 participants was 61.3% and 20.9%, respectively, which is higher than 34% and 7% of paediatric randomised controlled drug trials published in 2007.11 However, single-centre, non-blind research accounts for the majority of clinical trials in China. At the same time, 60.1% of clinical trials recruited both adult and paediatric patients. Trials design needs to be further strengthened.

The proportion of trials involving infants and newborns in China is lower than that in the paediatric randomised controlled drug trials published in 2007.11 In recent years, opportunistic sampling design, population pharmacokinetics model and model-based bridging approach have provided technical support for clinical trials of children’s drugs.12–14 China has also launched the construction of a clinical evaluation technology platform for children’s medicine, which will enhance the overall level of clinical research on children’s medicine in China.15 However, how to apply these techniques and methods to trials design needs further exploration.

Furthermore, about 100 trials involved Chinese traditional medicine. This is a real change compared with the traditional idea, which considered Chinese medicine as practical experiences. Indeed, the randomised clinical trials and longer term safety evaluation are urgently needed to develop evidence-based therapy with Chinese traditional medicine in children.

Conclusions

Paediatric drug trials in China made a significant progress in recent years. Innovative method and trial design optimisation should be encouraged to accelerate paediatric clinical research with joint efforts of regulator, scientist and clinicians. Pharmaceutical companies need to be further stimulated to carry out more high-quality clinical trials with support of paediatric drug legislation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: WZ had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: T-YW and WZ. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: G-xH, X-xY and WZ. Critical revision of the manuscript: all authors. The authors plan to disseminate the results to study participants.

Funding: This work is supported by National Science and Technology Major Projects for 'Major New Drugs Innovation and Development' (2017ZX09304029-002), Young Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province, Qilu Young Scholars Program of Shandong University, National Natural Science Foundation of China (81503163), Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Program of Shandong Province (2018WSB19010).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. zhao4wei2@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. European network for drug investigation in children. BMJ 2000;320:79–82. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis JM, Connor EM, Wood AJJ. The need for rigorous evidence on medication use in preterm infants: is it time for a neonatal rule? JAMA 2012;308:1435–6. 10.1001/jama.2012.12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gore R, Chugh P, Tripathi C, et al. Pediatric off-label and unlicensed drug use and its implications 2017;12:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Napoleone E. Children and ADRs (adverse drug reactions). Ital J Pediatr 2010;36:4 10.1186/1824-7288-36-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waisel DB. Moral responsibility to attain thorough pediatric drug labeling. Paediatr Anaesth 2009;19:989–93. 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasquali SK, Lam WK, Chiswell K, et al. Status of the pediatric clinical trials enterprise: an analysis of the US ClinicalTrials.gov registry. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1269–77. 10.1542/peds.2011-3565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pansieri C, Bonati M, Choonara I, et al. Neonatal drug trials: impact of EU and US paediatric regulations. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2014;99:F438 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner MA, Catapano M, Hirschfeld S, et al. Paediatric drug development: the impact of evolving regulations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2014;73:2–13. 10.1016/j.addr.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nor Aripin KNB, Sammons HM, Choonara I. Published pediatric randomized drug trials in developing countries, 1996-2002. Paediatr Drugs 2010;12:99–103. 10.2165/11316260-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LI J, Yan K, Kong YT, et al. A cross-sectional study of children clinical trials registration in the world based on ClinicalTrials. Chin J Evid Based Pediatr 2016;11:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aripin KNBN, Choonara I, Sammons HM. A systematic review of paediatric randomised controlled drug trials published in 2007. Arch Dis Child 2010;95:469–73. 10.1136/adc.2009.173591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leroux S, Turner MA, Guellec CB-L, et al. Pharmacokinetic studies in neonates: the utility of an opportunistic sampling design. Clin Pharmacokinet 2015;54:1273–85. 10.1007/s40262-015-0291-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao G-X, Huang X, Zhang D-F, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in children with nephrotic syndrome. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:1748–56. 10.1111/bcp.13605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao W, Le Guellec C, Benjamin DK, et al. First dose in neonates: are juvenile mice, adults and in vitro-in silico data predictive of neonatal pharmacokinetics of fluconazole. Clin Pharmacokinet 2014;53:1005–18. 10.1007/s40262-014-0169-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XL, Zhang YJ. The progress and prospects of pediatric clinical trial in China. J Pediatr Pharmacol 2011;17:15–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.