Abstract

Background

Elimination of cancer cells by some stimuli like chemotherapy and radiotherapy activates anticancer immunity after the generation of damage‐associated molecular patterns, a process recently named immunogenic cell death (ICD). Despite the recent advances in cancer immunotherapy, very little is known about the immunological consequences of cell death activated by cytotoxic CD8+ T (Tc) cells on cancer cells, that is, if Tc cells induce ICD on cancer cells and the molecular mechanisms involved.

Methods

ICD induced by Tc cells on EL4 cells was analyzed in tumor by vaccinating mice with EL4 cells killed in vitro or in vivo by Ag-specific Tc cells. EL4 cells and mutants thereof overexpressing Bcl-XL or a dominant negative mutant of caspase-3 and wild-type mice, as well as mice depleted of Tc cells and mice deficient in perforin, TLR4 and BATF3 were used. Ex vivo cytotoxicity of spleen cells from immunized mice was analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression of ICD signals (calreticulin, HMGB1 and interleukin (IL)-1β) was analyzed by flow cytometry and ELISA.

Results

Mice immunized with EL4.gp33 cells killed in vitro or in vivo by gp33-specific Tc cells were protected from parental EL4 tumor development. This result was confirmed in vivo by using ovalbumin (OVA) as another surrogate antigen. Perforin and TLR4 and BATF3-dependent type 1 conventional dendritic cells (cDC1s) were required for protection against tumor development, indicating cross-priming of Tc cells against endogenous EL4 tumor antigens. Tc cells induced ICD signals in EL4 cells. Notably, ICD of EL4 cells was dependent on caspase-3 activity, with reduced antitumor immunity generated by caspase-3–deficient EL4 cells. In contrast, overexpression of Bcl-XL in EL4 cells had no effect on induction of Tc cell antitumor response and protection.

Conclusions

Elimination of tumor cells by Ag-specific Tc cells is immunogenic and protects against tumor development by generating new Tc cells against EL4 endogenous antigens. This finding helps to explain the enhanced efficacy of T cell-dependent immunotherapy and provide a molecular basis to explain the epitope spread phenomenon observed during vaccination and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy. In addition, they suggest that caspase-3 activity in the tumor may be used as a biomarker to predict cancer recurrence during T cell-dependent immunotherapies.

Keywords: cytotoxicity, immunologic, T-Lymphocytes, immunogenicity, vaccine, dendritic cells, antigens

Background

In the past few years, a major understanding of the regulation of cancer immunity has allowed to develop new immunotherapy approaches that have shown unprecedented efficacy against aggressive bad prognosis cancers.1 2 Natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T (Tc) cells are the key responsible for the elimination of transformed cells during both cancer immunosurveillance and immunotherapy.3–6 However, meanwhile NK cells eliminate stressed tumor cells and/or cells that have downregulated major histocompatibilty complex (MHC)-I molecules,7 activation of Tc cells strictly depends on the recognition of antigens presented by MHC-I. Thus, the presence of tumor-mutated genes raising new epitopes/antigens (neoantigens) together with proper inflammatory signals leading to efficient antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells (DCs) are prerequisites for the generation of an effective Tc cell-mediated anticancer response.8 Accordingly, response to immunotherapy treatments that rely on T cell immunity, such as checkpoint antibody therapy, is limited to cancers that express immunodominant mutations that raise an optimal T cell response.

As an alternative to overcome this limitation, in recent years, it has been described that specific chemotherapy drugs and irradiation, in addition to kill cancer cells, have the capacity to prime anticancer immune responses against antigens released from dying cells, a concept known as immunogenic cell death (ICD).9–11 This process enhances the elimination of cancer cells and generates immune memory against the tumor antigens, reducing the chance of cancer recurrence.10 12 This ability is related to the activation of danger signaling pathways evoking emission of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) leading to inflammation, which favor DC maturation and antigen presentation.10 13–15 ICD increases the immunogenicity of tumor antigens that per se might present a lower antigenic potential and would not induce an efficient T cell response. In recent years, some molecular determinants that dictate the immunogenic characteristics of dying cells have been clarified.16 Apoptosis, ferroptosis, pyroptosis or necroptosis are among the different modalities of programmed cell death that can be immunogenic.17–20

Several molecules involved in the generation of eat-me and danger signals leading to ICD in cancer cells have been found such as exposure of calreticulin on the cell membrane, release of Hsp70 or HMGB1, autophagy and production of interleukin (IL)-1β or type I interferon (IFN).16 At present, the relative importance of each of these signals is not clear and different ICD signals have been described in cells dying under different stimuli. Thus, to find out if cancer cells eliminated by a specific stimulus undergo ICD, the generation of anticancer immunity and tumor development should be analyzed in vivo in animals previously immunized with dead cancer cells.

Despite the extensive studies focused on the mechanisms involved in tumor cell recognition by T cells, the molecular determinants that regulate cell death induced by Tc cells on cancer cells, a key event for successful cancer immunotherapy, are less characterized. Paradoxically, little is known about the immunogenic characteristics of cancer cell death induced by immunotherapy. Specifically, whether cell death induced by Tc cells is immunogenic and, if so, which are the mechanisms responsible for ICD induced by Tc cells?

Tc cells mainly use two pathways to kill cancer cells, death ligands (ie, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, fas ligand and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL)) or granule exocytosis.21 22 The later consists of the release of a pore-forming protein perforin (perf) that delivers a family of serine-proteases, the granzymes (gzms) into the cytosol of target cells. Gzms are the ultimate responsible (mainly gzmB) for cancer cell elimination. Apart from regulating target cell death, it was shown that gzms are involved in antigen cross-presentation of dying cells by somehow regulating DC phagocytosis.23 In a recent work, we have shown that Tc cells efficiently eliminate in vivo tumor cells expressing pro-tumorigenic and/or anti-apoptotic mutations.24 These results provided the molecular basis to explain the efficacy of immunotherapy against multidrug-resistant bad prognosis cancer. However, these findings raise a new question to predict refractoriness and/or cancer relapse after immunotherapy: is Tc cell mediated-elimination of cancer cells immunogenic? And if so, what is the impact of mutations in cell death/prosurvival pathways on the immunogenicity of cancer cell death induced by Tc cells?

Here we have employed the EL4 lymphoma mouse model and different cancer vaccination strategies based on the gp33 and OVA tumor Ag models to explore the immunogenic characteristics of cell death induced by Tc cells on cancer cells and the mechanisms involved in this process both in vitro and in vivo. Our results show that T cell cytotoxic activity on tumor cells induces ICD and promotes a protective immune response in vivo, priming the generation of new CD8+ Tc cell responses against endogenous tumor antigens. Importantly, this response is able to reduce tumor development in mice challenged with a second tumor. Additionally, our results show that expression of active caspase-3 is key for ICD induced by CD8+Tc cells.

Methods

Mouse strains

Inbred C57BL/6 (B6) and mouse strains deficient for perf (perfKO) and TLR4 (TLR4KO), bred on the B6 background, were maintained at the Center for Biomedical Research of Aragon (CIBA) and analyzed for their genotypes as described.25 Mouse strains deficient for BATF3 (BATF3KO) on the C57BL/6 background were kindly given by Dr David Sancho (Research Center for Cardiovascular Diseases Carlos III, Madrid, Spain). Mice from both sexes and 8–10 weeks of age were used.

Cell lines, cell culture and reagents

EL4, EL4.DNC3 and EL4.Bcl-XL cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium with 5% heat-inactivated FBS at 37°C. EL4 cells overexpressing Bcl-XL or expressing a dominant negative mutant of caspase-3 (Cys285Ala; DNC3; Genscript)26 were generated by lentiviral infection employing the pBABE-puro vector containing the cDNA of the proteins and the psPAX and pMD2.G vectors containing the HIV-1 Gag and Pol and VSV Env proteins, respectively. Transfected cell clones were selected by limiting dilution, employing conditioned medium and puromycin as antibiotic of selection.

Mouse vaccination and isolation of ex vivo CD8+Tc cells

Mice were immunized with LCMV-WE intraperitoneal (105 pfu) in 200 μL of RPMI 2% heat-inactivated FBS. On day 8 postinfection, CD8+ cells were positively selected from spleen using α-CD8-MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) and a MACS-cell separation system and resuspended in RPMI 5% heat-inactivated FBS before use in cytotoxic assays. Purity of selected CD8+ cells was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) staining and found to be between 95% and 98%.

Ex vivo cytotoxicity assays

Target cells were preincubated with the LCMV-derived peptide gp33 (Neosystem Laboratoire) and MACS-enriched ex vivo virus immune CD8+ T cells were stained with CellTracker Green (CTG; Invitrogen). Effector and target cells were incubated at different ratios depending on the conditions (10:1, 7:1, 3:1, 1:1 (effector:target)) at 37°C. In some experiments, unselected immune splenocytes from immunized mice were incubated with fluorescently labeled target cells at 100:1 ratio. Subsequently, phosphatidyl serine (PS) exposure on plasma membrane (Annexin V staining) and incorporation of 7-AAD were measured by three-color flow cytometry in the target population with a FACSCalibur (BD Pharmingen) and CellQuests software described previously.27

IL-1β release in cell culture supernatants was quantified using a Ready-SET-Go ELISA Set from eBioscience. HMGB1 release in cell culture supernatants was quantified using a kit from Finetest Biotechnolgy. Calreticulin exposure on plasma membrane was measured by flow cytometry using a specific antibody anti-mouse calreticulin from Abcam (clon EPR3924, PE).

Generation of mouse bone marrow–derived dendritic cells

DCs were generated from bone marrow cells using wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 mice, in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% of FCS serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin/streptomycin, 50 mM of 2-ME and 10% of supernatant of X63Ag8653 cell cultures as source of GM-CSF (Zal et al, 1994) (DC medium). Cells were cultured on 100 mm petri dishes (1×106 cells/10 mL DC culture medium). On days 3 and 5, the cell medium was refreshed. On day 7, supernatants contained cells, which showed differentiated morphology and expressed the DC markers CD11c+, MHC-II low and CD40 low, confirming their identity as immature DCs. For their maturation, these DCs were incubated with LPS 1 µg/mL for 20 hours.

Tumor development

Non-pulsed or gp33-pulsed EL4 cells were inoculated intraperitoneally or subcutaneously in mice following the different protocols described. For pulsed cells, EL4 cells were incubated with 100 nM gp33 or 1 μM OVA peptide for 1 hour at 37°C and washed before inoculation. In some experiments, mice were injected with 100 µg of anti-CD8β mAb (clon H35-17.2) or the same amount of rat isotype control before injecting tumor cells.

Subcutaneous tumor development was analyzed by measuring tumor volumes every second day. Volume was calculated using the equation formula W x L x H, where W, L and H represent the width, length and height of the tumor. Mice were sacrificed when they reach the humane endpoint as established by the Animal Ethics Committee (volume larger than 0.5 cm3 or presenting signs of ulceration).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. The difference between means of unpaired samples was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s post-test or using unpaired t-test as indicated. Survival curves were compared using log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). The results are given as the CI with p values and are considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

EL4 cells killed by Ag-specific CD8+ Tc cells express ICD signals

We have previously shown that Ag-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CD8+ Tc cells) eliminate EL4 lymphoma cells in vitro and in vivo, independently of the apoptotic mitochondrial pathway, caspases, necroptosis and pyroptosis by a mechanism involving granule exocytosis.24 This was demonstrated using different cell lines expressing anti-apoptotic mutations. Thus, we now aimed to analyze if the target cells killed in vitro by CD8+ Tc cells express some of the molecular immunogenic determinants and the effect of the cell death mutations indicated above. To this aim, we focused on some danger signals previously described to participate in ICD induced by other anticancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy: calreticulin membrane exposure (CRT) and IL-1β and HMGB1 release.28–30 CRT is an ‘eat-me’ signal that contributes to the uptake of dying cells by DCs. The nuclear protein HMGB1 is released when nuclear membrane is disrupted, acting as a danger signal. IL-1β is a well-known inflammatory cytokine.

As shown in figure 1A, and confirming previous findings,24 ex vivo gp33-specific Tc cells induced the same level of cell death in parental EL4 cells as in the EL4.DNC3 and EL4.Bcl-XL mutant cells, being most cells eliminated at 3:1 effector:target ratio. A summary of the gating strategy shown in online supplementary figure 1. As previously found,24 cell death is delayed in the presence of Q-VD-OPh (figure 1A); thus, we required to increase effector:target ratio to 7:1 to get similar levels of dead cells to be used in the immunization protocols later on. It should be noted that at this time point (20 hours) all cells are positive for AAD, indicating that they have permeabilized plasma membrane. However, this effect is due to secondary necrosis observed in culture since at earlier time points (1–2 hours) most cells present an apoptotic phenotype, presenting PS translocation in the absence of membrane permeabilization.24Next, we analyzed the indicated ICD signals (figure 1B–D). In order to compare the results in conditions with the same level of cell death, a higher effector:target ratio was used when Q-VD was included. CRT exposure was analyzed in 7AAD negative cells to prevent staining of intracellular CRT (online supplementary figure 1). CD8+ Tc killing dramatically increased CRT exposure in EL4.gp33 cells compared with EL4 control cells, and this was prevented if killing was performed in the presence of Q-VD or using target cells expressing the caspase-3 mutant, EL4DNC3.gp33 (figure 1B). In contrast, EL4 target cells overexpressing Bcl-XL(EL4Bcl-XL.gp33) exposed CRT at the same level as EL4.gp33 cells following Tc cell killing. In all cases, CRT exposure was higher than the level of cell death (see figure 1A) and it was significantly reduced in the presence of QVD or in EL4DNC3 cells, even when cell death was not affected (see figure 1A), confirming that CRT exposure is not a consequence of membrane permeabilization during cell death.

Figure 1.

EL4.gp33 cells killed by antigen-specific Tc cells express immunogeneic cell death signals. (A) EL4 cells and mutants thereof (Bcl-xL and DNC3) were incubated with ex vivo gp33-specific CD8+ T cells from virus-immunized C57BL/6 mice in the presence of the gp33 Ag for 20 hours at the indicated effector:target ratios. Subsequently, phosphatydilserine exposure on plasma membrane and cell membrane integrity were measured by three-color flow cytometry using Annexin-V and 7-AAD as described in the Methods section. Data are represented as mean±SD of four independent experiments using eight mice in total. (B–D) EL4 cells and mutants thereof (Bcl-XL and DNC3) were incubated with ex vivo gp33-specific CD8+ T cells from virus-immunized C57BL/6 mice in the presence of the gp33 Ag for 20 hours at 1:1 effector:target ratio. A higher effector:target ratio (3:1) was used when QVD (30 µM) was included. Non-pulsed EL4 cells incubated with Tc cells and gp33-EL4 cells alone were used as controls. (B) Calreticulin exposure was analyzed by flow cytometry as indicated in the Methods section. (C, D) HMGB1 and interleukin (IL)-1β was measured in cell supernatants by ELISA. Data are represented as the mean±SD of four independent experiments, where *p<0,1; **p<0,01; ***p<0001, analyzed by unpaired t-test.

jitc-2020-000528supp001.pdf (700.6KB, pdf)

HMGB1 was significantly increased in supernatant from EL4.gp33 cells incubated with gp33-specific Tc cells compared with that from EL4 cells (figure 1C). In addition, HMGB1 was not released from activated Tc cells, confirming its specific release from dying EL4.gp33 cells. In contrast with CRT exposure, HMGB1 release was independent of caspase-3 inhibition or mutation.

IL-1β in supernatant from EL4.gp33 cells incubated with gp33-specific Tc cells was also increased compared with control cells, gp33-specific Tc cells or non-pulsed EL4 cells incubated with gp33-specific Tc cells. IL-1β production was reduced by QVD, likely due to inflammatory caspase inhibition. In contrast, IL-1β concentration was not reduced in EL4DNC3 or EL4.Bcl-XL cells.

These results show that Ag-specific CD8+Tc cells induce three main hallmarks of ICD in tumor dying EL4 cells, CRT exposure and HMGB1 and IL-1β release and indicate that these signals are differentially regulated by caspases and caspase-3.

Immunization with EL4.gp33 cells killed by gp33-specific Tc cells generates CD8+ T cell-mediated protection against EL4 tumor development

Despite the ability of Tc cells to induce ICD signals in target cells, this finding does not imply that this process is able to induce anticancer immunity against dying cancer cells. To decipher whether elimination of cancer cells by Tc cells is actually immunogenic, we analyzed if tumor elimination by Tc cells resulted in the priming of the host immune system against endogenous tumor antigens different from those involved in the cytotoxic killing of the tumor by the gp-33-specific Tc cells. We set up a model of whole-cell tumor vaccination employing gp33-pulsed EL4 cells (EL4.gp33) killed by gp33-specific Tc cells ex vivo as indicated in figure 1A and subsequently used to immunize C57Bl/6 (B6) wt mice. This model is summarized in figure 2A. For simplicity, we will refer to cells killed under this protocol as EL4.gp33TcLCMV. As control, one group was inoculated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) -and another one was inoculated with the same amount of activated gp33-specific Tc cells alone (TcLCMV group) in order to analyze if immunomodulatory cytokines produced by Tc cell might contribute to tumor immunogenicity. After 7 days, mice were challenged with parental EL4 cells in the right flank, and tumor development was monitored. As shown in figure 2B, tumor growth was delayed and survival was longer in mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells, compared with control groups (figure 2B). In addition, we found a slight but significant increase in CD4+ and CD8+ infiltrating T cells in mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells compared with PBS control (figure 2C). However, CD8+ T cells also increased in mice inoculated with TcLCMV cells alone, which were not protected from tumor development, indicating that increased infiltration is not sufficient for protection. These results indicate that immunization with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells generates a protective immune response against parental EL4 cells. In addition, the data indicate that the potential immunomodulatory effect of activated Tc cells is not sufficient to provide any protection against tumor development.

Figure 2.

EL4.gp33 cells killed ex vivo by gp33-specific Tc cells generate protection against EL4 tumors. (A) EL4 cells were incubated with ex vivo gp33-specific CD8+ T cells from virus-immunized C57BL/6 mice in the presence of the gp33 Ag for 20 hours at an effector:target ratio 3:1. After this time, cell cultures were collected and used to immunize C57B/L6 mice intraperitoneal at day 0 and day 7 (EL4.gp33TcLCMV=gp33-EL4.gp33 cells+gp33 Tc cells). In the gp33-Tc cell group (TcLCMV), mice were immunized with the equivalent number of gp33-specific Tc cells (1.5×106 cells). As control, mice were immunized with PBS. At day 14, the three groups were inoculated with 2×105 EL4 cells in the right flank. (B) Tumor development was monitored over 25 days as described in the Methods section. The data correspond to 10 mice from two independent experiments, where ***p<0001. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) in the survival graph. (C) In some mice, tumors were removed and TIL composition was analyzed by flow cytometry using the indicated cell markers. The data correspond to five mice from two independent experiments, where *p<0,1; **p<0,01; analyzed by unpaired t-test. (D) The same experiment as shown in (A) was performed but employing wild-type (WT) and perfKO mice or mice depleted of CD8+ T cells using an anti-CD8β monoclonal antibody (days 13, 17, 21 and 25). The data correspond to 10 mice from two independent experiments, where ***p<0001. Two-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) in the survival graph. (E) In some mice, tumors were removed and TIL composition was analyzed by flow cytometry using the indicated cell markers. The data correspond to five mice from two independent experiments, where *p<0,1; **p<0,01. Analyzed by unpaired t-test.

To find out whether the secondary protective response is dependent on anti-tumoral CD8+ Tc cells generated against EL4 endogenous Ags, we immunized mice (following the protocol indicated in figure 2A) in which CD8+ T cells had been depleted or mice lacking the cytotoxic molecule perforin (perfKO). While mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells developed significantly smaller tumors and survived significantly longer than control mice, perfKO mice or those lacking CD8+ Tc cells lost this protection (figure 1D). Similar to the results obtained in figure 2C, immunization with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells significantly increased the % of CD3+/CD4+ T cells and CD3+/CD8+ T cells in wt mice (figure 2E). There were not significant differences between wt and and perfKO mice, further indicating that the absence of tumor protection in perfKO mice was not due to a reduction in the generation/infiltration of CD8+ Tc cells. In conclusion, protective response to EL4 secondary challenge is dependent on CD8+ T cell perforin-dependent killing activity against EL4 cells after immunization with dying EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells.

BATF3-dependent dendritic cells and TLR4 are required for priming of new EL4-specific CD8+ Tc

To demonstrate that new CD8+ Tc cells are primed against endogenous antigens expressed on EL4 cells, we analyzed whether blockade of Ag cross-priming affected protection against EL4 tumor development after vaccination with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells. BATF3-deficient mice, which lack cDC1s specialized in tumor Ag cross-presentation,31 32 and TLR4-deficient mice, which lack a pathway of sensing HMGB1 involved in antigen processing for cross-presentation,28 were immunized following the protocol indicated in figure 2A. Notably, protection to EL4 secondary challenge conferred by immunization with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells was lost in TLR4KO and BATF3KO mice (figure 3A). This result suggests the priming of new CD8+ T cells against endogenous EL4-derived Ags by cDC1s and using a TLR4-dependent pathway for improved Ag cross-presentation.

Figure 3.

BATF3 and TLR4 are required for the generation of cancer immunity after immunization with dead EL4 cells. (A) EL4 cells were incubated with ex vivo gp33-specific CD8+ T cells from virus-immunized C57BL/6 mice in the presence of the gp33 Ag for 20 hours at an effector:target ratio 3:1. After this time, cell cultures were collected and used to immunize wild-type (wt), TLR4KO and BATF3KO mice at day 0 and day 7. As control, mice were immunized with PBS. On day 14, mice were inoculated with 2×105 EL4 cells in the right flank. Tumor development was monitored over 25 days as described in the Methods section. The data correspond to 10 mice from two independent experiments, where ***p<0001. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) in the survival graph’s. WT, TLR4KO and BATF3KO mice were immunized with gp33-pulsed EL4 dead cells as indicated in (A). On day 10, splenocytes from these mice were isolated and incubated at an effector:target ratio 100:1 with EL4 cells in the presence or absence of the viral peptide GP33. After 18 hours, PS exposure on plasma membrane was measured by three-color flow cytometry using Annexin-V. Data are represented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments using six mice in total, where *p<0,1; analyzed by unpaired t-test.

Subsequently, to confirm CD8+ Tc cell cross-priming, we analyzed the generation of specific CD8+ Tc cells against EL4 endogenous Ags in wt and TLR4KO and BATF3KO mice. Since EL4 endogenous tumor Ags are not known, it is not possible to analyze the generation of Ag-specific CD8+ T cells by conventional multimer staining.

Thus, we tested ex vivo the anti-tumoral activity of spleen cells from control and immunized mice against EL4 cells. Spleen cells from wt mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells showed increased killing capacity of EL4 cells compared with spleen cells from non-immunized control, TcLCMV immunized mice or EL4.gp33TcLCMV-immunized mice deficient in TLR4 or BATF3 (figure 3B). These results show that BATF3 and TLR4-dependent cross-priming to dying EL4.gp33TcLCMV generates an effective Tc response to endogenous EL4 Ags that is dependent on granule exocytosis (figure 2).

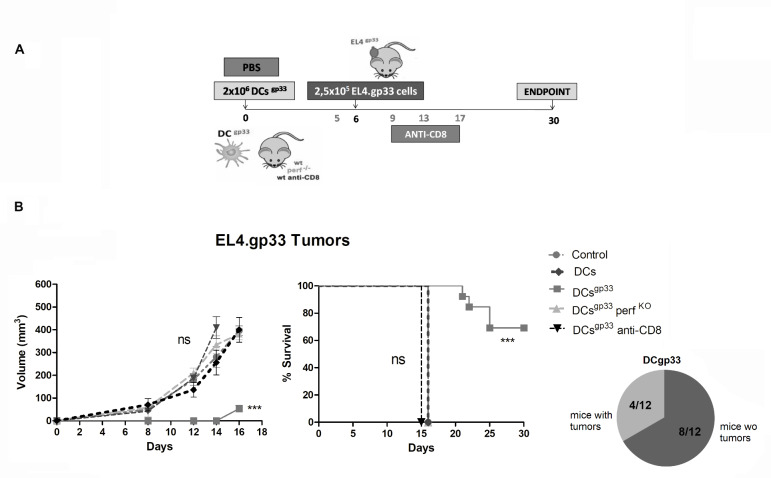

Gp33-specific CD8+Tc killing in vivo also protects against EL4 secondary challenge

To demonstrate whether Ag-specific CD8+Tc cell killing in vivo was immunogenic, we employed a clinical relevant immunotherapy protocol consisting of vaccination with DCs loaded with gp33 Ag (DCgp33) (figure 4A). This protocol has shown good efficacy in vivo n mice using other antigen models.33 A summary of the protocol used is depicted in figure 4A. Immunization with mature DCgp33 conferred a large protection against EL4.gp33 tumor development compared with mice non-immunized or those immunized with DCs matured but without gp33 (figure 4B). Protection against EL4.gp33 tumor development was completely abrogated when CD8+ T cells were depleted or in perfKO mice (figure 4C). These results indicate that immunization with mature DCgp33 generates a CD8+ T cell-dependent and perf-dependent protection against EL4 tumor development, showing that this model is suitable to analyze immunogenicity of cell death induced by CD8+ Tc cells in vivo.

Figure 4.

Vaccination with dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with gp33 induces Tc cell-dependent protection against EL4.gp33 tumors. Upper panels: C57BL/6 WT, perfKO mice or mice depleted of CD8+ T cells using an anti-CD8β monoclonal antibody (days 5, 9, 13 and 17) were inoculated with PBS (control) or with 2×106 mature DC alone (DC) or incubated with gp33 peptide (DCgp33) intraperitoneal on day 6, the three groups were inoculated with 2.5×105 gp33-EL4 cells in the right flank. Tumor development was monitored over 50 days as described in the Methods section. The data correspond to 12 mice from three independent experiments, where ***p<0.001. Two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox).

Next, we analyzed if the elimination of EL4.gp33 cells in vivo in mice immunized with DCgp33 (from now on EL4.gp33TcDC cells) generated a protective response against parental EL4 tumors. Mice inoculated with mature DCgp33 developed EL4 tumors and reach the endpoint on day 15 (DCgp33, figure 5A), similar to control non-immunized mice (figure 3A). In contrast, EL4 tumor development was largely reduced and survival increased in mice immunized following the protocol EL4.gp33TcDC (figure 5A). This tumor protection was lost on CD8+ T cell depletion, showing that elimination of parental EL4 cells was dependent on the generation of new CD8+ Tc cells specific against EL4 endogenous antigens. A similar result was found, when the same protocol was performed, but using the OVA antigen instead of gp33. In this case, elimination of EL4OVA cells in vivo in mice immunized with DCOVA generated a protective response that significantly delayed the growth of parental EL4 tumors (online supplementary figure 2), indicating that immunization against endogenous EL4 tumors was independent of the antigen model.

Figure 5.

EL4.gp33 cells killed in vivo after immunization with dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with gp33 protects against EL4 tumor development. (A) C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with mature gp33-DCs. On day 6, the control group was inoculated with PBS (control) and the rest of groups were inoculated with 2.5×105 gp33-EL4 cells in the right flank (EL4.gp33TcDC). On day 20, all groups were inoculated with 2×105 EL4 cells in the left flank. In one group of mice CD8 cells were depleted employing an anti-CD8β monoclonal antibody (days 19, 23, 27 and 31) (EL4.gp3TcDC anti-CD8). Tumor development was monitored over 50 days as described in theMethods section. The data correspond to 12 mice from three independent experiments, where ***p<0.001. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). (B) C57BL/6 wt and BATF3KO mice were inoculated with 3×106 mature DCs (LPS 1 µg/mL 20 hours) incubated with gp33 peptide via intraperitoneal. On day 6, one group was inoculated with PBS (Tc wt DCsgp33, Tc BATF3KO DCsgp33) and the other group was inoculated with 5×105 gp33-EL4 cells in the right flank (TC wt EL4.gp33TcDC, Tc BATF3KO EL4.gp33TcDC). Seven days later, mice were sacrificed, CD8+ Tc cells from the spleen and lymph nodes were enriched by MACS and transferred (6×106 cells) into C57BL/6 wt mice, who had been inoculated with 1.5×105 EL4 cell. Tumor development was monitored over 20 days as described in the Methods section. The data correspond to five mice from one experiment, where **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox).

jitc-2020-000528supp002.pdf (55.6KB, pdf)

To confirm that CD8+ Tc cells cross-primed against dying EL4.gp33-derived antigens were the responsible of EL4 tumor elimination, we employed an adoptive transfer protocol using CD8+T cells from wt and BATF3KO mice, previously immunized following the protocol EL4.gp33TcDC (figure 5B). Only those mice transferred with CD8+ Tc cells from EL4.gp33TcDC immunized wt mice showed protection against EL4 tumor development compared with mice transferred with Tc from wt mice immunized with DCgp33, or Tc coming from BATF3-deficient mice independently of the immunization stimulus (figure 5B). These results show that in vivo elimination of EL4.gp33 cells by gp33 Ag-specific CD8+Tc cells is immunogenic and cross-primes a CD8+ Tc cell response against endogenous EL4-derived antigens, suggesting that is a general mechanism of epitope spreading not only applicable to adoptive T cell transfer but also to DC vaccination strategies for cancer immunotherapy.

Role of caspases and the mitochondrial cell death pathway in ICD induced by CD8+ Tc cells

Finally, we wondered how the mutations on cell death pathways analyzed in figure 1 in vitro would affect the immune response against tumor Ags derived from cancer cells eliminated by Tc cells in vivo. To this aim, we analyzed the role of caspases and the mitochondrial cell death pathway in the generation of immunity against EL4 tumor development after vaccination. The level of protection offered by EL4.gp33 cells killed in vivo after DCgp33 vaccination was much pronounced as compared with the protocol employing EL4.gp33 killed in vitro (figures 5 and 2). However, in order to reduce the number or mice and to study the mechanism in a more controlled way, we followed the vaccination protocol with EL4.gp33 killed in vitro (EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells), using EL4.gp33 wt cells as well as mutants thereof overexpressing Bcl-XL or expressing a dominant negative caspase-3 mutant (DNC3). In addition, we used EL4.gp33 wt cells in which caspases were blocked with the pan-inhibitor Q-VD-OPh.

Mice were immunized employing the cells killed in figure 1A, following the protocol indicated previously (figure 2). As shown in figure 6A, mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells were protected against tumor development and survived significantly longer than non-immunized control mice. In contrast, protection disappeared in those mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV cells that had been killed in the presence of Q-VD, indicating that functional caspases are required to generate protection against parental EL4 tumor development. A similar result was found when EL4DNC3.gp33TcLCMV cells were used. The protection observed after immunization with EL4.gp33TcLCMV was lost when cells expressed the caspase-3 mutant (EL4DNC3.gp33TcLCMV, figure 6B). In contrast, mice immunized with EL4Bcl-XL.gp33TcLCMV cells were protected and developed EL4 tumors significantly smaller and survived significantly longer than non-immunized control mice (figure 6B). Although tumors were slightly bigger than mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV, neither tumor growth nor mouse survival was significantly different. Therefore, this result suggests that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway is dispensable for CD8+ Tc-induced ICD in EL4 tumor model, which critically depends on the presence of active caspase-3.

Figure 6.

Role of caspases and Bcl-xL in the generation of immunity against EL4 antigens. (A) EL4 cells were incubated with ex vivo gp33-specific CD8+ T cells from virus-immunized C57BL/6 mice in the presence of the gp33 Ag for 20 hours at an effector:target ratio 3:1 (EL4.gp33TcLCMV Group) or at an effector:target ratio 7:1 in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh (30 µM; EL4.gp33TcLCMV + Q VD group). After this time, cell cultures were collected and used to immunize C57B/L6 mice via intraperitoneal. At day 0 and day 7, as control, mice were immunized with PBS. On day 14, the different groups were inoculated with 2×105 EL4 cells in the right flank. Tumor development was monitored over 25 days as described in the Methods section. The data correspond to 12 mice from three independent experiments, where ***p<0.001. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). (B) The same experiment as in (A) was performed but using EL4 cells and the mutants thereof overexpressing Bcl-XL or DNC3. The data correspond to 12 mice from three independent experiments, where **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post test and log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). (C) wt mice were immunized with the indicated gp33-pulsed EL4 dead cells killed as indicated in (A), with PBS (CTR) or with gp33-specific Tc cells (TcLCMV). On day 10, splenocytes from these mice were isolated and incubated at an effector:taget ratio 100:1 with EL4 cells in the absence of the viral peptide gp33. After 18 hours, PS exposure on plasma membrane was measured by three-color flow cytometry using Annexin-V. Data are represented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments, using six mice in total, where *p<0.05, analyzed by unpaired t-test.

To confirm the role of caspase-3 in ICD induced by CD8+Tc cells, we analyzed the generation of EL4-specific CD8+ Tc cells after immunization with EL4.gp33 dead cells. Splenocytes from mice immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV showed increased killing of parental EL4 cells in vitro compared with splenocytes from control mice or those immunized with EL4.gp33TcLCMV killed in the presence of Q-VD or with EL4DNC3.gp33TcLCMV cells (figure 6C). Cytotoxic activity of splenocytes from mice immunized with EL4Bcl-XL.gp33TcLCMV cells was similar to that from EL4.gp33TcLCMV immunized mice. These results confirm that caspase-3, but not the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, is required for ICD induced by CD8+ Tc cells, including the generation of a protective anti-tumor CD8+ Tc cell response.

Discussion

A major understanding of the regulation of CD8+ Tc cell-mediated immunity in cancer has been key to successfully treat mutated bad prognosis cancers with immune checkpoint inhibitors or with modified CAR-T cells. However, the number of patients benefiting from immunotherapy is still relatively low and restricted to a small proportion of some types of cancer. The factors contributing to immunotherapy efficacy and tumor resistance and/or relapse are poorly explored. We have recently shown that antigen-specific Tc cells are able to eliminate tumor cells expressing anti-apoptotic mutations conferring bad prognosis and drug resistance, preventing tumor development in vivo.24 However, it is unclear if these mutations may affect tumor relapse. Here, employing two different models of cancer vaccination in mice and the EL4 lymphoma model, we show that elimination of cancer cells by antigen-specific CD8+ Tc cells ex vivo and in vivo is immunogenic and generates a secondary protective immune response against endogenous tumor antigens. Importantly, specific mutation of the cell death executioner caspase-3, although did not affect cell killing and elimination of primary tumors completely abrogated the generation of protective CD8+ Tc cell response against secondary tumor development. This finding indicates that ICD induced by CD8+ Tc cells and the generation of spread immunity against endogenous tumor antigens rely on caspase-3-dependent apoptosis of EL4 cancer cells.

Although we have mainly used a model of tumor antigen derived from the LCM virus, gp33 antigen, this should not be a major limitation to extrapolate our findings to other immunotherapies, like those employing viral infections (oncolytic viruses) and others.34 First, ICD induced by Tc cells has been confirmed in vivo using a conventional approach consisting of vaccination with peptide (gp33) pulsed bone marrow–derived DCs, which has been previously shown to offer CTL priming and tumor immunity.33 In addition, the affinity of the antigen T cell receptor for viral gp33 is similar to that one for ‘real’ tumor antigens like MelA or gp100.35 36 This affinity is even higher for engineered T cell receptors as in CAR-T cells. Anyway, we have confirmed that our results are not restricted to gp33-antigen since elimination of EL4.OVA cells in mice vaccinated with OVA-pulsed bone marrow–derived DCs significantly delayed the development of parental EL4 tumors. Thus, the use of two different surrogate antigens supports the conclusion that our results are not influenced by the selection of specific surrogate tumor antigens. Moreover, a similar result in other tumor models employing different tumor antigens has been shown by Ignacio Melero’s group in an accompanying paper37 reinforcing that ICD induced by Tc cells is not restricted by specific antigens.

The concept of immunogenic cell death raised from the observation that cancer cells eliminated by specific chemotherapy drugs or radiotherapy induced the generation of protective CD8+ Tc cells against antigens released by dying tumor cells.9 10 14 15 20 This response contributed to the elimination of the tumor cells and, in addition, it was shown to prevent cancer recurrence.9 28 Since then, several stimuli have been found to induce ICD on cancer cells including irradiation, hyperthermia, infection or cell starvation.16 However, and paradoxically, studies addressing if cell death induced by CD8+ Tc cells is immunogenic are scarce.

Protection correlates with the generation of well-known ICD signals in dying cancer cells: calreticulin membrane exposure and the release of HMGB1 and the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β.16 However, several signals have been associated to ICD induced by different stimuli. Thus, analyzing the effect of in vivo immunization with dead cells on tumor development is mandatory to analyze if cell death induced by a specific stimulus is immunogenic. Here an important question to genuinely identify ICD on cancer cells is the potential direct in vivo immunomodulatory effects of the stimulus used to kill the cancer cells used for the immunization. For example, different drugs, commonly referred to as ICD inductors, are capable to induce tumor cell death as well as to directly modulate the immune system in vivo making it impossible to attribute the observed biological effects solely to ICD, unless they are removed before immunization. Activated Tc cells also produce several immunomodulatory cytokines that might contribute to the effects observed in vivo in our study. Having in mind this possibility, our study included different controls suggesting that a direct effect of Tc cells is not the responsible of the protection observed during vaccination with dead EL4 tumor cells. First, inoculation of mice with activated Tc cells alone has no effect on tumor development. On top of that, immunization with the mixture of activated Tc cells and dead tumor cells, killed in the absence of caspase-3 activity, did not confer any protection against tumor development. An optimal approximation would be to separate the cell debris from Tc cells after the killing assay. However, this approximation is challenging and would likely change the immunogeneic properties of cell debris like the presence of soluble factors released by dying cells. Thus, being aware of this difficult limitation to overcome the in vivo vaccination experiments strongly support for an immunogeneic phenotype of cell death induced by CD8+ Tc cells.

We find herein that general caspase inhibition as well as caspase-3 inhibition impairs immunogenicity and spread immunity against endogenous tumor antigens. However, the role of specific caspases seems to be dependent on the stimuli used29 38 39 and likely the tumor cell type. Our results show that, at least in EL4 lymphoma cells, caspase-3 plays a key role in ICD induced by CD8+ Tc cells since vaccination with dying EL4 cells expressing the DN caspase-3 mutant does not stimulate the generation of CD8+ Tc cells against endogenous EL4 antigens and does not protect against secondary tumor development. In contrast to caspase-3, the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway does not seem to be involved in ICD induced by CD8+ Tc cells since Bcl-XL overexpression had no effect.

Further confirming that Tc cells induce ICD in tumor cells, we show that the protective effect is loss in mice deficient in TLR4 or in BATF3-dependent DCs. TLR4 is a receptor for HMGB1, a DAMP that interacts with TLR4 in DCs for an efficient processing and cross-presentation of antigens derived from cells killed by chemotherapy or radiotherapy.28 40 Regarding BATF3-dependent cDC1s, they are involved in phagocytosis and cross-presentation of antigens from dying cells, contributing to protection against some but not all viral, bacterial and fungal infections.31 41 A previous study found out that tumor cells killed by OT1-specific Tc cells induced antigen cross-presentation by DCs.23 However, that study did not analyze whether this killing was immunogenic in the tumor context and whether it conferred a protective immune response against tumor development. Our data show that cancer cells killed by Tc cells bear an ICD that promotes cross-presentation by cDC1s, which are specifically required for antitumor immunity following ICD induction by Tc cells. These results concur with the essential role of cDC1s in tumor vaccination42 and its association with improved overall survival in several tumors.43 Indeed, BATF3 is required for an efficient generation of Tc cell immunity against primary immunogenic tumors.31 In addition, BATF3-dependent DCs modulate the efficacy of different immunotherapy protocols including adoptive T cell therapy or mAb against immune checkpoints.32 43 44 Our data show the requirement of cDC1 for generation of an efficient protective immunity against endogenous antigens expressed in dead tumor cells following Tc-induced ICD. Remarkably, cDC1s are not essential for antitumor immunity following other models of ICD.45

As indicated above, our results have been independently confirmed using other cancer immunotherapies and different tumor models, including transgenic T cell receptors and NK cells.37 Recent findings in clinical trials employing T cell-based cancer immunotherapy support the novelty, the conceptual advance and the potential clinical relevance of our results. It has been recently found that during CAR-T cell therapy in gastric cancer, new T cell clones against tumor neoantigens are detected in patients, a concept known as epitope spreading.46 Epitope spreading was also observed during cancer vaccination in humans,47 although the molecular basis for this phenomena remained unexplored. Our results provide an explanation and the molecular mechanism involved in that observation, enhancing our mechanistic knowledge to design rational new vaccines and other T cell-based therapies to overcome antigen loss or the absence of known antigens, a problem commonly observed during cancer vaccination and CAR-T cell therapy. These new protocols may include approaches to overcome potential tumor evasion strategies to counteract epitope spread.

Conclusions

Using a mouse in vivo model of cancer immunotherapy, we have found that CD8+ Tc cells induce ICD on cancer cells, generating spread immunity and a protective Tc cell response against endogenous tumor antigens. The mechanism involved depends on the presence of active caspase-3 and is independent of the mitochondrial cell death pathway. These findings indicate that ICD and epitope spreading during cell death induced by CD8+ Tc cells contribute to the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Moreover, our findings suggest that mutations in caspase-3 or in pathways regulating its activity might increase the risk of tumor refractoriness and/or recurrence after T cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Clinical trials will be required to test whether the presence of caspase-3 mutations and/or inhibitors like XIAP can be used as biomarkers to predict relapse during immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the use of Servicios Científico Técnicos del CIBA (IACS-Universidad de Zaragoza) and Servicios Apoyo Investigación de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

Footnotes

Correction notice: Since the online publication of this article, it was noticed that notes to production were left in the main text. The article has been updated to remove these.

Contributors: PJS designed and performed experiments and wrote the fist draft of the manuscript; IUM performed experiments; NA developed and characterized EL4.Bcl-XL cells; MAA designed and performed experiments; DS and SCK provided BATF3-deficient mice and OT1 transgenic mice, designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; JP conceived and designed the original study and wrote the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Funding: Work in the JP laboratory is funded by Asociacion de Padres de Niños con Cancer de Aragon (ASPANOA), FEDER (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional, Gobierno de Aragón(Group B29_17R) and Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación e Universidades (MCNU), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (SAF2014-54763-C2-1 and SAF2017‐83120‐C2‐1‐R). Predoctoral grants/contracts from Fundación Santander/Universidad de Zaragoza (MA), and Gobierno de Aragon (IUM, PJS) and a postdoctoral Juan de la Cierva Contract (MA). JP is supported by ARAID Foundation. Work in the DS laboratory is funded by the CNIC, from Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación e Universidades (MCNU), Agencia Estatal de Investigación and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) (SAF2016-79040-R) and the European Research Council (ERC-2016-Consolidator Grant 725091). The CNIC is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), the MCNU and the Pro CNIC Foundation, and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (SEV-2015-0505).

Competing interests: JP reports research funding from BMS and Gilead and speaker honoraria from Gilead and Pfizer.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All experiments were performed in accordance with FELASA guidelines under the supervision and approval of Comité Ético para la Experimentación Animal (Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation) from the University of Zaragoza (number: PI33/13).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. All data are included in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Melero I, Berman DM, Aznar MA, et al. . Evolving synergistic combinations of targeted immunotherapies to combat cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015;15:457–72. 10.1038/nrc3973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018;359:1350–5. 10.1126/science.aar4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnet FM. The concept of immunological surveillance. Prog Exp Tumor Res 1970;13:1–27. 10.1159/000386035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. . Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol 2002;3:991–8. 10.1038/ni1102-991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The three ES of cancer immunoediting. Annu Rev Immunol 2004;22:329–60. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vesely MD, Kershaw MH, Schreiber RD, et al. . Natural innate and adaptive immunity to cancer. Annu Rev Immunol 2011;29:235–71. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:225–74. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finn OJ. Human tumor antigens yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:347–54. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, et al. . Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-beta-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med 2005;202:919–29. 10.1084/jem.20050463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, et al. . Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy. Annu Rev Immunol 2013;31:51–72. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, et al. . Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature Committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ 2018;25:486–541. 10.1038/s41418-017-0012-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallach D, Kang T-B. Programmed cell death in immune defense: knowledge and presumptions. Immunity 2018;49:19–32. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg AD, Galluzzi L, Apetoh L, et al. . Molecular and translational classifications of DAMPs in immunogenic cell death. Front Immunol 2015;6:588. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green DR, Ferguson T, Zitvogel L, et al. . Immunogenic and tolerogenic cell death. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:353–63. 10.1038/nri2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, et al. . Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:860–75. 10.1038/nrc3380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galluzzi L, Buqué A, Kepp O, et al. . Immunogenic cell death in cancer and infectious disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2017;17:97–111. 10.1038/nri.2016.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloy N, Garcia P, Laumont CM, et al. . Immunogenic stress and death of cancer cells: contribution of antigenicity vs adjuvanticity to immunosurveillance. Immunol Rev 2017;280:165–74. 10.1111/imr.12582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue H, Tani K. Multimodal immunogenic cancer cell death as a consequence of anticancer cytotoxic treatments. Cell Death Differ 2014;21:39–49. 10.1038/cdd.2013.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rufo N, Garg AD, Agostinis P. The unfolded protein response in immunogenic cell death and cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2017;3:643–58. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandenabeele P, Vandecasteele K, Bachert C, et al. . Immunogenic apoptotic cell death and anticancer immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016;930:133–49. 10.1007/978-3-319-39406-0_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A, Pardo J. How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:5047–56. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voskoboinik I, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. Perforin and granzymes: function, dysfunction and human pathology. Nat Rev Immunol 2015;15:388–400. 10.1038/nri3839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoves S, Sutton VR, Haynes NM, et al. . A critical role for granzymes in antigen cross-presentation through regulating phagocytosis of killed tumor cells. J Immunol 2011;187:1166–75. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaime-Sánchez P, Catalán E, Uranga-Murillo I, et al. . Antigen-Specific primed cytotoxic T cells eliminate tumour cells in vivo and prevent tumour development, regardless of the presence of anti-apoptotic mutations conferring drug resistance. Cell Death Differ 2018;25:1536–48. 10.1038/s41418-018-0112-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pardo J, Balkow S, Anel A, et al. . Granzymes are essential for natural killer cell-mediated and perf-facilitated tumor control. Eur J Immunol 2002;32:2881–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Snipas SJ, et al. . Mechanism-based inactivation of caspases by the apoptotic suppressor p35. Biochemistry 2001;40:13274–80. 10.1021/bi010574w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Catalán E, Jaime-Sánchez P, Aguiló N, et al. . Mouse cytotoxic T cell-derived granzyme B activates the mitochondrial cell death pathway in a Bim-dependent fashion. J Biol Chem 2015;290:6868–77. 10.1074/jbc.M114.631564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. . Toll-Like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat Med 2007;13:1050–9. 10.1038/nm1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, et al. . Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med 2007;13:54–61. 10.1038/nm1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghiringhelli F, Apetoh L, Tesniere A, et al. . Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in dendritic cells induces IL-1beta-dependent adaptive immunity against tumors. Nat Med 2009;15:1170–8. 10.1038/nm.2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, et al. . Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science 2008;322:1097–100. 10.1126/science.1164206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sánchez-Paulete AR, Cueto FJ, Martínez-López M, et al. . Cancer immunotherapy with immunomodulatory Anti-CD137 and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies requires BATF3-Dependent dendritic cells. Cancer Discov 2016;6:71–9. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paglia P, Chiodoni C, Rodolfo M, et al. . Murine dendritic cells loaded in vitro with soluble protein prime cytotoxic T lymphocytes against tumor antigen in vivo. J Exp Med 1996;183:317–22. 10.1084/jem.183.1.317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vile RG. The immune system in oncolytic Immunovirotherapy: gospel, Schism and heresy. Mol Ther 2018;26:942–6. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cole DK, Pumphrey NJ, Boulter JM, et al. . Human TCR-binding affinity is governed by MHC class restriction. J Immunol 2007;178:5727–34. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stone JD, Chervin AS, Kranz DM. T-Cell receptor binding affinities and kinetics: impact on T-cell activity and specificity. Immunology 2009;126:165–76. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03015.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minute L, Teijeira A, Sanchez-Paulete AR. Cellular cytotoxicity is a form of immunogenic cell deathJournal for immunotherapy of cancer. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2020;8:e000325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Brockmeier U, et al. . Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. Embo J 2009;28:578–90. 10.1038/emboj.2009.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casares N, Pequignot MO, Tesniere A, et al. . Caspase-dependent immunogenicity of doxorubicin-induced tumor cell death. J Exp Med 2005;202:1691–701. 10.1084/jem.20050915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, et al. . The interaction between HMGB1 and TLR4 dictates the outcome of anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Immunol Rev 2007;220:47–59. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00573.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez-López M, Iborra S, Conde-Garrosa R, et al. . Batf3-dependent CD103+ dendritic cells are major producers of IL-12 that drive local Th1 immunity against Leishmania major infection in mice. Eur J Immunol 2015;45:119–29. 10.1002/eji.201444651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wculek SK, Amores-Iniesta J, Conde-Garrosa R, et al. . Effective cancer immunotherapy by natural mouse conventional type-1 dendritic cells bearing dead tumor antigen. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:100. 10.1186/s40425-019-0565-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Böttcher JP, Reis E Sousa C, Reis ESC. The role of type 1 conventional dendritic cells in cancer immunity. Trends Cancer 2018;4:784–92. 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B, et al. . Tumor-Residing Batf3 dendritic cells are required for effector T cell trafficking and adoptive T cell therapy. Cancer Cell 2017;31:711–23. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma Y, Adjemian S, Mattarollo SR, et al. . Anticancer chemotherapy-induced intratumoral recruitment and differentiation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity 2013;38:729–41. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heckler M, Dougan SK. Unmasking pancreatic cancer: epitope spreading after single antigen chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in a human phase I trial. Gastroenterology 2018;155:11–14. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drake CG. The potential role of antigen spread in immunotherapy for prostate cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2014;12:332–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2020-000528supp001.pdf (700.6KB, pdf)

jitc-2020-000528supp002.pdf (55.6KB, pdf)