Abstract

Background:

Young adults (YAs) who engage in simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM) may combine substances due to enhanced subjective effects, and as a result, may place greater value (e.g., spend more resources) on alcohol relative to YAs who consume alcohol but do not engage in SAM. The aim of the current study was to evaluate behavioral economic demand for alcohol among YAs who reported SAM (n = 101) relative to alcohol use only (n = 316), and concurrent alcohol and marijuana use (CAM; n = 63).

Methods:

YAs (18-25 years old) recruited from the community completed an online assessment that included the Alcohol Purchase Task as well as past month alcohol, marijuana, and SAM use.

Results:

Analyses of covariance demonstrated that YAs who reported SAM had significantly higher Omax values (maximum overall expenditures on alcohol) than those who reported CAM, and both YAs who reported SAM and alcohol-only had significantly higher Pmax values (maximum inelastic price per drink) than YAs who reported CAM.

Conclusions:

YAs that engage in SAM show an increased willingness to spend resources on alcohol. Elevated demand is not associated with concurrent use of multiple substances, but rather the combined (i.e., overlapping) use of substances.

Keywords: Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use, young adults, behavioral economics, alcohol demand, reinforcing value

Introduction

Many young adults (YAs) who consume alcohol and marijuana use both simultaneously such that their effects overlap.1,2 Compared to alcohol use or marijuana use only, simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM) has consistently shown to result in harmful outcomes including more subjective negative physiological and cognitive effects, greater harm related to social relationships, finances, employment, or physical health, and more traffic collisions.3-6 Recent trends toward the legalization of recreational marijuana highlight the need to improve our understanding of the relationship between alcohol and marijuana use.

YAs may engage in SAM to experience additive subjective effects of combining the two substances. Compared to YAs who use alcohol only, those who engage in SAM may place greater value on alcohol (i.e., be willing to spend more resources on alcohol) because the additive effects may enhance the reinforcing value of alcohol. Behavioral economic models of substance misuse provide a framework for evaluating the extent to which individuals value a substance as a function of various costs.7 A substance’s reinforcing value, also referred to as an individual’s demand for a substance, can be assessed using variations of purchase tasks that ask individuals to report the amount of a substance he or she would consume across a number of varying prices (e.g., Alcohol Purchase Task8 [APT]). Alcohol demand curves plotting consumption as a function of cost can be generated resulting in several demand metrics that are associated with alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and severity of alcohol dependence.9

To date, previous studies have demonstrated elevated alcohol demand among drinkers who also use tobacco,10,11 and co-users of alcohol and marijuana.12 However, no studies have specifically compared demand among YAs who engage in SAM to YAs who engage in concurrent alcohol and marijuana use (CAM, i.e., recent reports of both alcohol and marijuana use but not simultaneously or overlapping5) to distinguish these unique types of co-users. The aim of the current study was to compare alcohol demand between YAs who engage in SAM, CAM, or alcohol use only (i.e., no marijuana use).

Methods

Participants and institutional review

Participants were a subsample of YAs from the community participating in a longitudinal study investigating social role transitions and substance use. Eligible participants were between the ages of 18-23 at screening, resided within 60 miles of the study location, had a valid email address, were willing to visit the study offices for a baseline assessment, and reported any past year alcohol consumption. Data for the present study were from a single monthly survey for which the APT was added to and only includes participants who reported drinking alcohol in the preceding month (N=480, 59.6% female, Mage=21.9, 62.9% White). The university’s institutional review board approved all procedures and measures and a federal Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Procedures

Eligible YAs who were interested in the study made an appointment to complete consent procedures and an in-person baseline assessment at the study office (N=779 enrolled in the longitudinal study). All follow-up monthly surveys were completed online.

Measures

Alcohol, marijuana, and SAM.

Two single items assessed the number of drinking days and marijuana use days in the past month, (coded as 0=none, 1=at least one day). For marijuana users, SAM was assessed with a single item “How many of the times when you used marijuana did you use it at the same time as alcohol – that is, so that their effects overlapped?” with responses coded as 0=none and 1=at least once. These alcohol, marijuana, and SAM variables were used to classify YAs as belonging to one of three groups: 1) Alcohol-only (n=316): Reported alcohol but no marijuana/SAM in past month, 2) CAM (n=63): Reported alcohol and marijuana use but no SAM (i.e., no overlapping effects) in past month, and 3) SAM (n=101): Reported alcohol, marijuana, and SAM (i.e., alcohol and marijuana effects overlapped) in past month. Defining SAM by relying on interpretation of overlapping effects is a common way to characterize SAM and is the current standard for national studies including the Monitoring the Future study.13-15 Typical weekly alcohol consumption in the past month was assessed with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ)16 which asks participants to provide the number of standard drinks consumed on each day of a typical week in the last month.

Alcohol demand.

The Alcohol Purchase Task (APT)8 assessed alcohol demand. Participants were presented with a hypothetical scenario at a party to see a band for four hours and were asked to report the number of standard drinks they would purchase and consume across 19 price intervals per standard drink ranging from $0 to $20.00. Participants were instructed to assume that they did not drink or use other drugs before or after the party. Participants’ consumption and expenditure reports across these price intervals yielded five indices of alcohol demand: Intensity (number of standard drinks consumed at free cost), Omax (maximum total expenditure on alcohol), Pmax (price per drink at which demand curve shifts from inelastic [i.e., change in price has smaller effects on consumption] to elastic [i.e., change in price has larger effects on consumption]), breakpoint (price per drink at which consumption ceases) and elasticity (rate of reduction in consumption as a function of price). Intensity, Omax, Pmax, and breakpoint were derived from the raw data, whereas elasticity was calculated by fitting each participant’s reported consumption across the range of prices (with removal of zero values) to an equation17: log Q = 1og Q0 + k (e −αP – 1), where Q represents the quantity consumed, Q0 represents consumption at price = 0, k specifies the range of the dependent variable (alcohol consumption) in logarithmic units, P specifies price, and α specifies the rate of change in consumption with changes in price (elasticity). A k value of 3.4 was set constant for all participants and was determined by entering all data into GraphPad Prism 7.03 for Windows,18 and selecting the “Shared between 0 and 10” option.

Data analysis plan

Values on demand indices equal to or greater than 3.29 SD above the mean were changed to one unit greater than the largest non-outlier value.19 Elasticity values were transformed using square root transformation due to significant positive skewness. To initially characterize the subgroups, descriptive statistics were obtained and groups were compared without controlling for covariates. To test the primary study aims, separate analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were run to examine group differences on each demand metric while controlling for age, sex, and past month alcohol consumption. Tukey post hoc tests examined pairwise group differences.

Results

Descriptive statistics

On average, participants reported consuming 5.80 standard drinks per week (SD=7.85) in the past month. Regarding alcohol demand, the mean number of drinks at free cost (intensity) was 5.63 (SD=3.08), the mean maximum overall expenditure on alcohol (Omax) was $14.51 (SD=9.37), the mean price per drink at which inelastic consumption shifts to elastic consumption (Pmax) was $5.82 (SD=4.42), and the mean price per drink at which participants would stop purchasing a standard drink (breakpoint) was $11.10 (SD=6.11). Thirty-four percent of this sample reported past month marijuana use, and of those, 61.6% reported past month SAM. Descriptive statistics between groups on indices of demand and typical drinking are shown in Table 1. YAs who report SAM had significantly greater intensity and Omax values, and greater typical drinking relative to YAs who report CAM and alcohol use only. YAs who report SAM had significantly greater Pmax values and lower elasticity values relative to YAs who report CAM only.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Subgroups of User Status: Percentage or Mean (Standard Deviation)

| User Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Alcohol-only users (n = 316) |

CAM users (n = 63) |

SAM users (n = 101) |

F |

| Age | 21.88 (1.74) | 21.87 (1.85) | 21.83 (1.60) | 0.03 |

| Percent Women | 61.4 | 58.7 | 54.5 | - |

| Drinks per week1 | 4.71 (6.01)a | 4.84 (7.61)a | 9.83 (11.18)b | 17.82*** |

| Monthly Income | 1036.46 (1030.31) | 989.18 (1057.51) | 1002.40 (909.00) | 0.08 |

| Intensity | 5.43 (3.07)a | 5.27 (3.07)a | 6.46 (2.98)b | 4.78** |

| Omax | 13.98 (8.98)a | 12.56 (8.69)a | 17.35 (10.39)b | 6.66*** |

| Pmax | 5.93 (4.45)a,b | 4.54 (4.01)a | 6.26 (4.47)b | 3.28* |

| Breakpoint | 11.16 (6.12) | 10.36 (6.77) | 11.38 (5.63) | 0.58 |

| Elasticity | .072 (.021)a,b | .074 (.022)a | .066 (.020)b | 4.11* |

Note. CAM = Concurrent Alcohol and Marijuana; SAM = Simultaneous Alcohol and Marijuana;

Derived from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire and represent typical drinks per week consumed in the past month; Intensity represents hypothetical alcohol consumption at free cost; Omax represents maximum overall expenditures on alcohol; Pmax represents maximum inelastic price; Breakpoint represents price per drink at which consumption ceases; Elasticity represents rate of consumption reduction as a function of price with greater values indicating greater sensitivity to increases in price. F values come from ANOVAs examining group differences on continuous variables without controlling for covariates. Post-hoc analyses indicate significant subgroup differences among subgroups that do not share superscript values.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

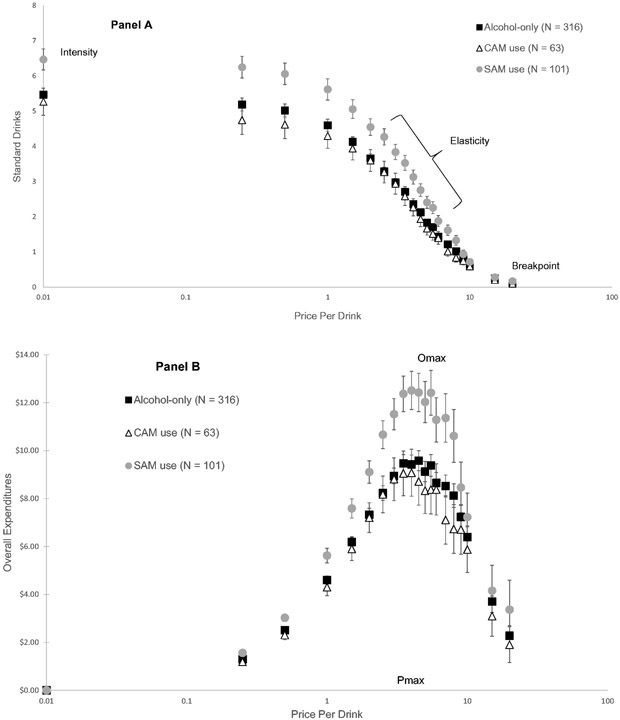

Group differences in demand

Figure 1 presents alcohol consumption in standard drinks (Panel A) and overall expenditures (Panel B) as a function of price per drink. After controlling for age, sex, and typical alcohol consumption, ANCOVAs revealed a significant main effect of user status on Omax, F(2,475)=3.60, p=.028. Follow-up comparisons revealed that YAs who report SAM had significantly greater maximum overall expenditures on alcohol relative to YAs who report CAM (p=.034), that is YAs that report SAM would spend more money overall on alcohol compared to YAs that report CAM. There was also a significant main effect of user status on Pmax, F(2,475)=3.50, p=.031. Follow-up analyses revealed that YAs who report SAM and alcohol use only had significantly greater Pmax values relative to YAs who report CAM (p’s <.05), that is demand for alcohol among YAs who report CAM shifts from inelastic to elastic at a lower price per drink suggesting a greater sensitivity to increases in price. There were no significant effects of user status on the intensity, breakpoint, or elasticity indices of alcohol demand after controlling for covariates (p’s >.05).

Figure 1. Alcohol Demand Curves.

Mean self-reports on the Alcohol Purchase Task plotted in double logarithmic coordinates for proportionality and shown separately for young adults that report alcohol use only (n = 316), young adults that report concurrent alcohol and marijuana use (CAM use; n = 63), and young adults that report simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use (SAM use; n = 101). Panel A shows alcohol consumption in standard drinks, and Panel B shows overall alcohol expenditures, both plotted as a function of price per drink. Error bars represent ±1 standard error of the mean.

Conclusions

The current study examined whether YAs who engage in SAM exhibit greater behavioral economic demand for alcohol relative to YAs who engage in CAM or only use alcohol. Descriptively, YAs who report SAM demonstrated elevated demand for alcohol on metrics indicating greater hypothetical consumption of alcohol at free cost (intensity), greater overall expenditures on alcohol (Omax), and less sensitivity to increasing costs of alcohol consumption (Pmax and elasticity) compared to YAs who report CAM. However, YAs who report SAM also reported significantly greater past month alcohol consumption, and some group differences in demand were accounted for by differences in drinking levels. After controlling for differences in typical drinking, YAs who report SAM had greater Omax values compared to those who report CAM, and both those who report SAM and alcohol-only had greater Pmax values compared to YAs who report CAM. Although past research has shown elevated demand among tobacco users and co-users of alcohol and marijuana,10-12 this is the first study to demonstrate elevated demand unique to YAs who engage in SAM highlighting differences in alcohol valuation between subgroups of alcohol and marijuana co-users.

One possibility why group differences emerged is that YAs who engage in SAM may value alcohol more as the combined subjective effects of SAM may be more reinforcing. This notion is supported by past research demonstrating a positive association between SAM and motives to use alcohol or marijuana to increase the effects of another substance.20 Alternatively, YAs who don’t combine alcohol and marijuana use and view these as substitute substances may value alcohol less because as the cost to drink alcohol increases, more affordable substitute substances may be available. Consistent with this notion, YAs who reported CAM had lower Pmax values than both YAs who reported SAM and alcohol use only, suggesting a greater sensitivity to increasing prices to drink. Cross-commodity purchase tasks, in which the price of one commodity varies while holding the price of a second commodity fixed at a single price,21 could be examined with both alcohol and marijuana to investigate whether patterns of complementing or substituting these substances differ between YAs who report SAM and CAM.

The study has several limitations. First, analyses were cross-sectional precluding causal inferences regarding SAM and alcohol demand. Second, the study did not assess marijuana demand and marijuana purchase tasks22,23 could be used to compare demand between YAs that engage in SAM, CAM, or marijuana use only. Third, the study was conducted in a state with legalized recreational marijuana use (for individuals 21 and older), and results may not generalize to individuals in states or countries without legalized recreational marijuana use. Finally, the current study first sought to examine whether YAs who report any SAM exhibit greater demand, but future studies may consider whether levels (i.e., quantity and frequency) of SAM are related to alcohol demand.

This study provides the first comparative examination of behavioral economic demand for alcohol among YAs that engage in SAM relative to YAs who engage in CAM or only use alcohol. Previous studies demonstrating elevated demand for alcohol among drinkers who use tobacco have hypothesized that co-users of multiple substances exhibit a hypersensitivity to rewards in general.10 Similarly, recent research found elevated behavioral economic demand among alcohol and marijuana co-users, however that study did not distinguish between those who use alcohol and marijuana simultaneously and those who do not.12 This study demonstrates key differences between these two groups, and found that elevated demand is not associated with concurrent use of multiple substances, but rather is associated with the combined (i.e., overlapping) use of substances. In conclusion, YAs who endorse SAM are a high-risk group for alcohol misuse given their greater willingness to spend resources on alcohol.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) R01AA022087 (PI: Lee), R01AA022087-03S1 (PI: Lee), F32AA025263 (PI: Cadigan), and by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) R21DA045092 (PI: Ramirez). NIAAA and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The opinions expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors.

References

- 1.Brière FN, Fallu JS, Descheneaux A, Janosz M. Predictors and consequences of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011;36:785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pape H, Rossow I, Storvoll EE. Under double influence: assessment of simultaneous alcohol and cannabis use in general youth populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CM, Cadigan JM, Patrick ME. Differences in reporting of perceived acute effects of alcohol use, marijuana use, and simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:391–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sewell RA, Poling J, Sofuoglu M. The effect of cannabis compared with alcohol on driving. Am J Addict. 2009;18:185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subbaraman MS, Kerr WC. Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the national alcohol survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:872–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Alcohol and marijuana use patterns associated with unsafe driving among US high school seniors: high use frequency, concurrent use, and simultaneous use. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: Reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:641–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacKillop J The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40:672–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amlung M, MacKillop J, Monti PM, Miranda RM Jr.. Elevated behavioral economic demand for alcohol in a community sample of heavy drinking smokers. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Clawson AH, Dennhardt AA, MacKillop J. Smokers report greater demand for alcohol on a behavioral economic purchase task. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:626–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris V, Patel H, Vedelago L, Reed DD, Metrik J, Aston E, MacKillop J, Amlung M. Elevated behavioral economic demand for alcohol in co-users of alcohol and cannabis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79:929–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patrick ME, Veliz PT, Terry-McElrath YM. High-intensity and simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among high school seniors in the United States. Subst Abus. 2017;38:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick ME, Kloska DD, Terry-McElrath YM, Lee CM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Patterns of simultaneous and concurrent alcohol and marijuana use among adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2018;44:441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White HR, Kilmer JR, Fossos-Wong N, Hayes K, Sokolovsky AW, Jackson KM. Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among college students: Patterns, correlates, norms, and consequences. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43:1545–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psychol Rev. 2008;115:186–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GraphPad Prism version 7.03 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, California, USA, www.graphpad.com [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabachnick B, Fidell L, eds. Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among US high school seniors from 1976 to 2011: Trends, reasons, and situations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters EN, Rosenberry ZR, Schauer GL, O’Grady KE, Johnson PS. Marijuana and tobacco cigarettes: Estimating their behavioral economic relationship using purchasing tasks. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25:208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aston ER, Metrik J, MacKillop J. Further validation of a marijuana purchase task. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins RL, Vincent PC, Yu J, Liu L, Epstein LH. A behavioral economic approach to assessing demand for marijuana. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22:211–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]