Abstract

Affect regulation models of eating disorder behavior, which predict worsening of affect prior to binge-eating episodes and improvement in affect following such episodes, have received support in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. However, limited work has examined the trajectories of affect surrounding binge eating in binge-eating disorder (BED). In the current study, ecological momentary assessment data from 112 men and women with BED were used to examine the trajectories of positive affect (PA), negative affect (NA), guilt, fear, hostility, and sadness relative to binge-eating episodes. Prior to binge episodes, PA significantly decreased, whereas NA, and guilt significantly increased. Following binge episodes, levels of NA and guilt significantly decreased, and PA stabilized. Overall, results indicate improvements in affect following binge-eating episodes, suggesting that binge eating may function to alleviate unpleasant emotional experiences among individuals with BED, which is consistent with affect regulation models of eating pathology. As improvements in negative affect were primarily driven by change in guilt, findings also highlight the relative importance of understanding the relationship between guilt and binge-eating behavior within this population.

Keywords: binge-eating disorder, affect, affect regulation, EMA

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent episodes of overeating accompanied by a sense of loss of control over eating. Although these episodes are associated with significant distress, the disorder is distinct from bulimia nervosa (BN), as individuals with BED do not engage in regular compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting) intended to prevent weight gain (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although BED commonly goes unrecognized by healthcare providers (Kornstein, Kunovac, Herman, & Culpepper, 2016), the disorder is more prevalent than anorexia nervosa (AN) and BN combined, affecting 3.5% of women and 2.0% of men within their lifetime (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007). Further, BED is associated with substantial chronicity, psychiatric and medical comorbidity including high rates of obesity, and psychosocial impairment (Grilo, White, & Masheb, 2009; Hudson et al., 2007). As roughly 50% of individuals who receive treatment for BED do not achieve binge-eating abstinence (Linardon, 2018), identification of maintaining factors that may operate as malleable treatment targets represents an essential step towards improving BED interventions.

Numerous theories highlight the role of emotional states in the etiology and maintenance of disordered eating (e.g., Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Wonderlich, Peterson, et al., 2015), giving rise to treatment approaches that target emotional functioning and dysregulation (e.g., Safer, Telch, & Chen, 2009; Wonderlich, Peterson, et al., 2015). Within these theories, disordered eating behaviors such as binge eating are conceptualized as maladaptive emotion regulation strategies intended to mitigate unpleasant emotional states. Accordingly, affect regulation models predict that as individuals experience worsening affect (i.e., increasing negative affect and/or decreasing positive affect), the likelihood that they will engage in disordered eating behaviors increases. Further, affect is hypothesized to improve following the behavior, contributing to disorder maintenance through a process of negative reinforcement (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991).

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is uniquely positioned to test the propositions forwarded by affect regulation models of disordered eating (Stone & Shiffman, 1994). This approach, which involves the repeated assessment of participants’ experiences (e.g., affective states) and behaviors (e.g., binge eating) in naturalistic settings, allows researchers to examine moment-to-moment changes in emotional experiences before and after engagement in disordered eating behaviors. Prior EMA work using multilevel modeling to track the rate and direction of changes in affect (i.e., trajectories) before and after binge-eating episodes has provided compelling support for affect regulation models in BN, AN, and obesity (Berg et al., 2015; Engel et al., 2013; Fischer et al., 2017; Smyth et al., 2007). More specifically, these studies consistently demonstrate that affect deteriorates in a curvilinear fashion prior to binge-eating episodes, and improves in a curvilinear fashion following binge episodes. That is, worsening of affect appears to accelerate in the minutes and hours closest to the binge, suggesting that a rapid deterioration in affect precedes and likely contributes to binge eating. Similarly, affect appears to improve relatively rapidly immediately following the binge, which likely serves to reinforce and maintain the behavior.

Although multilevel modeling analyses indicate precipitous decreases in negative affect following binge episodes, other work indicates that levels of negative affect may actually be higher after binge eating than before the behavior, suggesting that binge eating may not serve the hypothesized regulatory function (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011). Importantly, studies suggesting increases in post-binge negative affect have typically relied on an examination of simple differences in affect ratings made prior to and after binge episodes. This methodological feature is notable because researchers have raised concerns regarding the use of pre-post comparisons of affect in EMA studies. Specifically, some argue that statistical approaches which use all available data to model the trajectory of affect leading up to and following a binge represent a more stringent and appropriate test of affect regulation hypotheses than approaches which use data from a single time point before and after the behavior (see Berg et al., 2017 for further discussion of this issue). To our knowledge, no published study has examined trajectories of affect surrounding binge-eating episodes among a large sample of individuals with BED. As prior work indicates that individual eating disorder diagnoses may be associated with unique patterns of affective experience and emotional disturbance (Lavender et al., 2015), the application of multilevel modeling approaches to characterize the trajectories of affective experiences surrounding binge eating in BED represents an important contribution to the literature, allowing for a stringent test of affect regulation models in this population.

Notably, prior work suggests that individual facets of negative affect may exhibit divergent trajectories in the hours preceding and following binge-eating episodes. For example, extant work in BN samples suggests that although all four examined facets of negative affect (i.e., guilt, sadness, hostility, fear) significantly increased prior to and decreased following binge-eating episodes, reported levels of guilt at the point of the binge-eating episode (i.e., the intercept) were significantly higher than levels of sadness, fear, and hostility (Berg et al., 2013). Further, guilt was the only facet of negative affect that demonstrated significant changes before and after binge eating when controlling for the remaining facets (Berg et al., 2013). Similarly, among individuals with obesity, only guilt evidenced significant pre-binge increases and post-binge decreases, while levels of sadness, fear, and hostility remained stable throughout the pre- and post-binge period (Berg et al., 2015). These results indicate that binge eating may be differentially related to specific affective states, and uniquely related to guilt in particular. Notably, diagnostic criteria for BED within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) suggest that binge episodes are associated with experiences of depression and guilt for many individuals with the disorder. Given this, it is possible that momentary changes in guilt or sadness (a correlate of depressed mood) may be particularly relevant antecedents and/or consequences of binge eating in BED.

Although affect regulation models of eating pathology and associated interventions have primarily focused on changes in negative affect as the key precipitant and reinforcer of disordered eating behaviors, previous EMA studies using multilevel modeling of affect trajectories also indicate that positive affect decreases in a curvilinear manner prior to binge-eating episodes and increases in a curvilinear manner following binge episodes among individuals with BN (Smyth et al., 2007), with similar results reported in AN (Engel et al., 2013). These findings indicate a possible reward function of binge eating, suggesting that the behavior may be maintained via both positive and negative reinforcement processes. However, further work is needed to clarify the role of positive affect in BED.

In summary, affect regulation models of eating disorders have received empirical support in AN and BN (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), however, we are unaware of any published work that has examined the trajectories of momentary affect surrounding binge eating in large sample of individuals with DSM-5 BED using EMA. Such work is likely to have important implications for the treatment of this disorder. For example, interventions may seek to target affective experiences identified as common precipitants of binge-eating episodes by increasing patients’ awareness of these vulnerable states and encouraging adoption of alternative emotion regulation strategies during at-risk periods. Further, findings may be used to tailor ecological momentary interventions (e.g., just-in-time adaptive interventions, JITAIs), which harness ambulatory assessment data to deliver interventions to users in their natural environment during periods of elevated risk (Juarascio, Parker, Lagacey, & Godfrey, 2018; Smith et al., 2019). In addition, as treatment approaches commonly conceptualize improvements in affect as a maintenance mechanism for binge eating, information regarding the specific affective states most likely to be impacted by binge-eating episodes (e.g., negative affect versus positive affect), may help to inform reinforcement-based theories of binge-eating pathology, and guide associated intervention approaches.

In order to clarify the role of affective states in precipitating and maintaining binge-eating episodes among individuals with BED, the objectives of the current study were to utilize EMA to (a) examine the trajectories of negative affect and positive affect in relation to binge episodes, and (b) further clarify the pre- and post-binge trajectories of specific negative emotional states (i.e., guilt, sadness, hostility, fear) within a large BED sample. Based on findings in AN and BN (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), as well as experimental research supporting affect regulation models in BED (Leehr et al., 2015), it was hypothesized that global negative affect would increase prior to and decrease following binge-eating episodes, whereas positive affect was expected to demonstrate the opposite pattern. Based on findings from BN and obese samples (Berg et al., 2013; 2015), it was hypothesized that fluctuations in negative affect would be primarily driven by momentary changes in guilt.

Method

Participants

Participants for the current study comprised men and women enrolled in a randomized clinical trial comparing Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy (Wonderlich, Peterson, et al., 2015) to guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy (Fairburn, 2013) for BED (Peterson et al., 2020). Initially, 713 individuals were screened to assess eligibility for the trial (eligibility criteria are provided below) via phone and in-person assessment. Of those, 132 were eligible for participation and began the EMA protocol. Data from 20 participants who did not complete the full EMA protocol were excluded from analyses, resulting in the final sample of 112.

Study participants were required to be between the ages of 18 to 65 years old and meet criteria for DSM-5 BED (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Participants were excluded from the trial for the following reasons: (a) unable to read English, (b) BMI less than 21, (c) lifetime history of psychotic symptoms or bipolar disorder, (d) substance use disorder within 6 months of enrollment, (e) medical instability, (f) acute suicidality, (g) purging behavior (e.g., self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or diuretics) more than once per month for the previous 3 months, (h) current diagnosis of BN, (i) medical condition impacting eating or weight (e.g., thyroid condition), (j) history of gastric bypass surgery, (k) currently pregnant or lactating, (l) currently receiving weight loss or eating disorder treatment, (m) use of medication impacting eating or weight (e.g., stimulants), or (n) psychotropic medication changes in the 6 weeks prior to enrollment.

The final sample included nineteen (17.0%) individuals who identified as male, ninety-two (82.1%) who identified as female, and one individual (0.9%) who identified as transgender male to female. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 64 years (M = 39.7, SD = 13.4). Mean BMI was 35.1 kg/m2 (SD = 8.7). Most participants were Caucasian (91.1%), in a partnered relationship (78%), and had completed at least a bachelor’s degree (68.8%). Lifetime rates of DSM-IV Axis I disorders were 57.1% for mood disorders, 37.5% for anxiety disorders, and 39.3% for substance dependence.

Structured Interviews

Semi-structured interviews to assess for eating pathology and other psychiatric diagnoses were administered by trained assessors and supervised by an author with extensive experience in the assessment of psychopathology (CBP).

Eating Disorder Examination Interview (EDE).

The Eating Disorder Examination Interview Version 16.0 (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993; Fairburn, 2008), a semi-structured investigator-based interview, was used to assess eating disorder symptoms and determine the DSM-5 diagnosis of BED (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). All EDE interviews were recorded, and a random sample (n = 21, 19%) of these interviews was rated by an independent assessor to confirm current eating disorder diagnoses. Interrater reliability for current BED diagnosis was excellent with 100% agreement.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Version (SCIDI-/P).

The SCID-I/P (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995), a semi-structured interview which assesses current and lifetime history of DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders, was used to assess comorbid psychiatric diagnoses for study sample description.1 Modules assessing mood, psychotic, substance, anxiety, eating, adjustment, and somatoform disorders were administered.

EMA Measures

Following the semi-structured interviews, participants completed a 7-day EMA protocol to report experiences of affect and binge-eating behavior in the natural environment.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) is a self-report measure of both higher-order and lower-order dimensions of affect. Consistent with previous EMA research (e.g., Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), a subset of 21 items were selected from the 60-item PANAS-X (Watson & Clark, 1994) and 10-item PANAS-short form (Kercher, 1992) scales to reduce participant burden and measurement error due to fatigue. The administered items were chosen to represent the two higher-order dimensions of Positive Affect (five items: alert, inspired, determined, attentive, and active) and Negative Affect (five items: afraid, nervous, upset, ashamed, and hostile). In addition, as facets of negative affect have demonstrated differential relationships with binge eating among individuals with BN (Berg et al., 2013) and obesity (Berg et al., 2015), items were selected to represent the four facets of negative affect indexed by the PANAS-X, which are Fear (four items: scared, frightened, afraid, nervous), Guilt (four items: ashamed, disgusted with self, dissatisfied with self, angry at self), Hostility (four items: scornful, disgusted, hostile, disdainful), and Sadness (three items: lonely, sad, alone). Consistent with previous work (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), PANAS items were adapted to assess momentary affective experiences by asking participants to rate the degree to which they were currently experiencing each of the 21 examined affective states (e.g., “How upset are you feeling right now?”) on a 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) Likert-type scale. In the current sample, the internal consistency of the Negative and Positive Affect scales was .80 and .88, respectively. The internal consistency of the Negative Affect facet scales ranged from .81 to .91.

Eating disorder behaviors.

For all recorded eating episodes, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which the episode was characterized by both overeating and loss of control over eating on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). To assess overeating, participants rated the following two items: (a) “To what extent to do you feel that you overate?”, and (b) “To what extent do you feel that you ate an excessive amount of food?”. To assess loss of control, participants rated each of the following four questions: (a) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel a sense of loss of control?”, (b) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel that you could not resist eating?”, (c) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel that you could not stop eating once you had started?”, and (d) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel driven or compelled to eat?”. An eating episode was categorized as a binge if the episode was rated 4 or higher on at least one overeating item and at least one loss of control item. Previous work utilizing this definition of binge eating has demonstrated positive correlations between retrospective (EDE questionnaire version) and EMA assessments of binge eating among individuals with BN (Wonderlich, Lavender, et al., 2015).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from eating disorder clinics, community advertisements, and social media postings at two sites (Fargo, ND; Minneapolis, MN) to participate in a randomized controlled treatment trial for BED (Peterson et al., 2019). Eligible individuals attended an assessment visit, during which they received further information about the study, provided informed consent, and completed structured clinical interviews (EDE, SCID-I/P). Participants were then trained on the use of the phone-based EMA data-collection platform, and were instructed to complete EMA recordings over the next 7 days, prior to beginning the treatment trial. Participants were compensated with $150 after study completion. Institutional review board approval for the study was obtained at each site.

The EMA protocol utilized two types of daily self-report methods (Wheeler & Reis, 1991). For signal contingent recordings, participants completed assessments at five semi-random signals distributed around anchor points between 8 am and 10 pm. For interval contingent recordings, participants completed assessments at designated time intervals (i.e., at bedtime). At each recording, participants were asked to rate their current mood. In addition, they were asked to report any eating behaviors that had occurred since the last signal, as well the timing of that eating episode in order to locate the episode in time and establish temporality.

Statistical Analyses

Consistent with recommended approaches for testing affect regulation models (Berg et al., 2017), the pre- and post-binge trajectories of positive affect, negative affect, and each facet of negative affect (i.e., guilt, fear, sadness, hostility) were modeled separately using piecewise linear, quadratic, and cubic functions centered on the time at which the binge-eating episode occurred. This approach (referred to as mixed-effects polynomial regression models by Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006) was chosen because it allowed us to (a) model separate trajectories for antecedent (i.e., pre-binge) and consequent (i.e., post-binge) temporal patterns, (b) model nonlinear trajectories, (c) utilize data collected at differing time intervals, (d) include data with missing assessments, (e) handle binge episodes that occurred at differing time points, and (f) model nonlinear relationships across time both at the individual and population levels. Multilevel models in which momentary observations (Level 1) were nested within subjects (Level 2) estimated linear (time prior to the binge, time following the binge), quadratic ([time prior to the binge]2, [time following the binge]2), and cubic ([time prior to the binge]3, [time following the binge]3) effects. Quadratic and cubic effects were estimated to allow for the possibility of nonlinear trajectories, given prior work suggesting curvilinear changes in affect before and after binge episodes (e.g., Engel et al., 2013). The linear effect indicates whether the initial slope of the regression line (i.e., change in affect immediately prior to or following a binge episode) is increasing, decreasing, or flat. Moving away from the intercept (i.e., the point of the binge episode), the quadratic effect indicates whether the initial slope (from the linear component) deflects downward or upward. In other words, this reflects the acceleration or deceleration in rate of affect change. Finally, the cubic effect captures possible changes in the rate of affect change occurring most distal from the intercept, and indicates whether the initial deflection (from the quadratic component) intensifies or decelerates over time. Models specified a random intercept for subject and a common intercept for pre-and post-binge trajectories. For pre-binge trajectories, analyses examined whether the linear, cubic, and quadratic effects differed significantly from zero. For post-binge trajectories, analyses first examined whether the linear, cubic, and quadratic effects of the post-binge trajectory were significantly different from the pre-binge trajectory (i.e., did the trajectory of affect change after the binge-eating episode). Secondary analyses were performed to determine whether the post-binge trajectories significantly differed from zero (i.e., did affect following the binge significantly increase, decrease, or stay the same). For analyses involving the separate facets of negative affect, each facet was examined individually while controlling for the other facets (e.g., guilt was modeled controlling for fear, sadness, and hostility) in order to examine the unique effects of each facet. When more than one binge-eating episode was reported in a single day, only the first binge episode was used to avoid confounding the relationship between antecedent and consequent affect ratings. Effects for the linear, quadratic, and cubic functions were converted to standardized beta-weight values (β) to aid interpretation. Significance thresholds were corrected for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedures (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Consistent with recommendations (McDonald, 2014), the FDR significance level (Q) was set at .10.2 All analyses were conducted within SPSS version 25 using a first-order autoregressive covariance structure (AR1) to account for serial correlations. Maximum-likelihood estimation methods were used to estimate parameters. Random-effects pattern mixture modeling (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997) was used to examine the influence of missing data on affect trajectories. Specifically, a median split was used to divide participants into groups with high versus low levels of compliance based on their degree of missing data. Degree of compliance was then examined as a moderator of affect trajectories by examining the interaction between compliance group and all linear, quadratic, and cubic functions. Annotated SPSS syntax is provided as Supplemental Material, and de-identified data are available upon request.

Results

EMA Recordings and Missing Data

Participants reported a total of 508 binge-eating episodes, with an average of 4.54 (SD = 4.48) binge-eating episodes endorsed per participant over the 7-day recording period. A total of 881 antecedent affect ratings (M = 8.99, SD = 5.83 per person) and 675 consequent affect ratings (M = 7.34, SD = 5.89 per person) were reported relative to binge-eating episodes. Participant compliance, defined as the percentage of signal-contingent ratings that were completed for each prompt was 76%, which is similar to previous EMA work within eating disorder samples (e.g., Engel et al., 2013). Results from the random-effects pattern-mixture modeling analyses indicated that participant compliance (i.e., participants’overall level of missing data) did not impact affect trajectories as indicated by the lack of significant interactions between compliance group and temporal effects (i.e., linear, quadratic, cubic) (p values all > .05). Therefore, missing data were not imputed.

Affect Trajectories

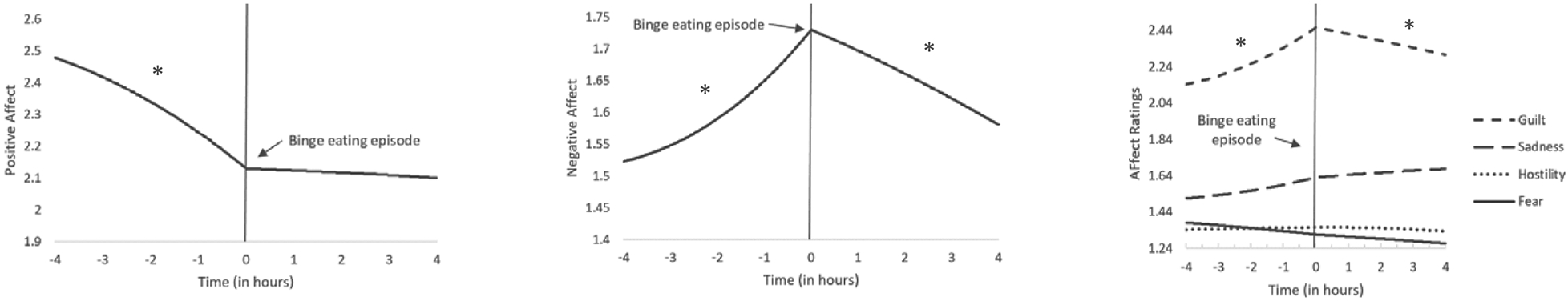

The results of analyses examining trajectories of affect are presented in Tables 1 and 2, and illustrated in Figure 1. Figures illustrating the 95% confidence intervals for negative and positive affect trajectories are provided as Supplemental Material. Below, we describe the significant standardized effects (β) following application of FDR procedures.

Table 1.

Within-Day Multilevel Models of Positive Affect and Negative Affect Relative to Binge Episodes

| Positive Affect | Negative Affect | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE(b) | 95% CI | β | t | B | SE B | 95% CI | β | t | |

| Intercept | 2.12 | .04 | 2.03, 2.20 | 49.17*a | 1.73 | .03 | 1.67, 1.80 | 51.52*a | ||

| Hours before binge | −.12 | .03 | −.18, −.07 | −.79 | −4.82*a | .09 | .02 | .06, .13 | .74 | 4.70*a |

| (Hours before binge)2 | −.01 | .00 | −.02, −.00 | −.51 | −2.14*a | .01 | .00 | .01, .02 | .76 | 3.20*a |

| (Hours before binge)3 | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.12 | −.73 | .00 | .00 | .00, .00 | .37 | 2.37*a |

| Hours after binge | .12 | .03 | .06, .17 | .57 | 4.24*a | −.13 | .02 | −.17, −.08 | −.76 | −5.81*a |

| (Hours after binge)2 | .01 | .01 | .00, .02 | .52 | 2.08* | −.01 | .0 | −.02, −.01 | −.78 | −3.24*a |

| (Hours after binge)3 | .00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | .04 | .29 | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.17 | −1.14 |

Note. b = Unstandardized beta coefficient; SE = Standard error; CI = Confidence interval. β = Standardized beta coefficient. Pre-binge trajectories assess whether the linear, quadratic, and cubic effects differ from zero. Post-binge trajectories assess whether the post-binge trajectory significantly differs from the pre-binge trajectory.

p < .05.

Indicates effect significant after applying Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedures.

Table 2.

Within-Day Multilevel Models of Fear, Guilt, Hostility, and Sadness Relative to Binge Episodes

| Fear | Guilt | Hostility | Sadness | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE(b) | 95% CI | β | t | b | SE(b) | 95% CI | β | t | B | SE(b) | 95% CI | β | t | B | SE(b) | 95% CI | β | t | |

| Intercept | .39 | .06 | .28, .50 | 6.87*a | .98 | .07 | .84, 1.12 | 13.80*a | .31 | .04 | .22, .39 | 7.04*a | .33 | .07 | .19, .48 | 4.55*a | ||||

| Hours before binge | −.02 | .02 | −.05, .02 | −.14 | −1.01 | .12 | .02 | .07, .17 | .67 | 5.18*a | .00 | .01 | −.03, .03 | .02 | .12 | .05 | .02 | .00, .09 | .29 | 2.10* |

| (Hours before binge)2 | −.00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | −.04 | −.21 | .01 | .00 | .01, .02 | 6.02 | 3.25*a | −.00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | −.01 | −.05 | .01 | .00 | −.00, .01 | .30 | 1.53 |

| (Hours before binge)3 | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.02 | −.19 | .00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | .30 | 2.35*a | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.00 | .02 | .00 | .00 | −.00, .01 | .15 | 1.08 |

| Hours after binge | .01 | .02 | −.03, .04 | .03 | .31 | −.16 | .03 | −.20, −.11 | −.66 | −6.21*a | −.00 | .02 | −.03, .03 | −.01 | −.01 | −.03 | .02 | −.08, .01 | −.16 | −1.39 |

| (Hours after binge)2 | .00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | .04 | .20 | −.01 | .01 | −.02, −.01 | −1.03 | −3.12*a | −.00 | .00 | −.01, .01 | −.07 | −.33 | −.01 | .01 | −.01, .00 | −.22 | −1.04 |

| (Hours after binge)3 | .00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | .06 | .50 | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.25 | −1.24 | .00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | .06 | .46 | −.00 | .00 | −.00, .00 | −.21 | −1.62 |

Note. b = Unstandardized beta coefficient; SE = Standard error; CI = Confidence interval. β = Standardized beta coefficient. Pre-binge trajectories assess whether the linear, quadratic, and cubic effects differ from zero. Post-binge trajectories assess whether the post-binge trajectory significantly differs from the pre-binge trajectory.

p < .05.

Indicates effect significant after applying Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedures.

Figure 1.

Temporal associations between affect and binge-eating episodes.

*Trajectory significantly different from zero after applying Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate procedures.

Positive affect.

Positive affect decreased in a curvilinear fashion prior to binge-eating episodes (linear estimate = −0.79; quadratic estimate = −0.51). That is, the rate of decline in positive affect accelerated in the hours closest to the binge episode. Following the binge, the trajectory of positive affect changed (linear estimate = 0.57; quadratic estimate = 0.52) such that the slope of the line began to flatten out, and no longer significantly differed from zero. In other words, the steep decline in positive affect observed prior to the binge-eating episode changed such that positive affect stabilized and remained at a constant level in the hours following the binge-eating episode.

Negative affect.

Negative affect increased in a curvilinear fashion prior to binge-eating episodes (linear estimate = 0.74; quadratic estimate = 0.76; cubic estimate = 0.37). That is, the rate of increase in negative affect accelerated in the hours closest to the binge episode. Following the binge, the trajectory of negative affect changed (linear estimate = −0.76; quadratic estimate = −0.78), such that it began to significantly decrease in a linear fashion (linear estimate = −0.24).

Fear.

Fear did not change significantly prior to binge-eating episodes. Following binge-eating episodes, the trajectory of fear did not change, and the slope of the line did not significantly differ from zero. In other words, fear remained relatively stable across the full eight hours surrounding the binge episode.

Guilt.

Levels of guilt significantly increased in a curvilinear manner prior to binge-eating episodes (linear estimate = 0.67; quadratic estimate = 6.02; cubic estimate = 0.30). That is, that rate of increase in guilt accelerated in the hours closest to the binge episode. Following binge episodes, the trajectory of guilt significantly changed (linear estimate = −0.66; quadratic estimate = −1.03), such that it decreased in a significant linear fashion (linear estimate = −0.20).

Hostility.

Hostility did not change significantly prior to binge-eating episodes. Following binge-eating episodes, the trajectory of hostility did not change, and the slope of the line did not significantly differ from zero. In other words, hostility remained relatively stable across the full eight hours surrounding the binge episode.

Sadness.

Sadness did not change significantly prior to binge-eating episodes. Following binge-eating episodes, the trajectory of sadness did not change, and the slope of the line did not significantly differ from zero. In other words, sadness remained relatively stable across the full eight hours surrounding the binge episode.

Discussion

The current study sought to examine patterns of affect surrounding binge eating among individuals with BED using EMA methodology. Results indicated that negative affect significantly increased in the hours preceding binge-eating episodes, and significantly decreased in the hours following these episodes. This pattern suggests that reductions in negative affect following binge-eating episodes may negatively reinforce binge-eating behavior, and increase the likelihood of future binge-eating episodes under conditions of increasing negative affect. Findings from the current study are consistent with affect regulation models of eating pathology (e.g., Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Wonderlich, Peterson, et al., 2015), as well as previous EMA work examining the role of negative affect in precipitating and maintaining disordered eating behaviors in AN and BN (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007).

Notably, when the individual facets of negative affect were examined (i.e., guilt, hostility, fear, sadness), antecedent increases and consequent decreases in negative affect appeared to be most strongly driven by intensifying experiences of guilt prior to the binge episode and reductions in guilt following the episode. Whereas DSM-5 criteria indicate that binge-eating episodes are associated with subsequent feelings of depression, disgust, and guilt among a portion of patients with BED, the current study found that binge eating led to momentary reductions in guilt with no immediate impact on feelings of sadness. Although the current findings may appear to be in conflict with DSM-5 criteria, it is possible (and, indeed, likely) that this acute post-binge phase is followed by increasing feelings of guilt and sadness (perhaps related to one’s binge eating). Thus, future research may seek to examine the impact of binge episodes on affect across a longer timescale.

Although results from the current study are consistent with previous work in BN (Berg et al., 2013) and obesity (Berg et al., 2015), which demonstrate reductions in guilt following binge-eating episodes, this finding remains somewhat counterintuitive. Why is it that individuals who commonly express feelings of guilt regarding their binge eating, nonetheless report relief from guilt immediately following engagement in the behavior? One plausible idea is that craving, which has been identified as an important factor contributing to binge-eating episodes (Moreno, Warren, Rodríguez, Fernandez, & Cepeda-Benito, 2009), plays a critical role in this process. It is possible that, as craving rises, individuals with BED may begin to anticipate an imminent binge-eating episode, precipitating feelings of guilt. That is, rising levels of guilt may serve as a mechanism linking increasing experiences of craving to binge eating. The overconsumption of food and subsequent physical discomfort which commonly characterize binge-eating episodes may operate to ameliorate momentary craving through basic satiety processes and food hedonics; within this context, individuals may experience momentary reductions in craving-related guilt. Consistent with this hypothesis, several studies suggest that individuals with binge-eating pathology experience increases in food craving prior to binge episodes, and reductions in craving following consumption of craved foods (e.g., Goldschmidt et al., 2014; Wonderlich et al., 2017). However, existing studies have not examined the proposed mediational pathways. Consequently, our understanding of the craving-emotion-binge sequence is unclear. Although the present data are consistent with the idea that guilt may mediate craving and binge eating, further testing is needed to carefully evaluate this hypothesis. More broadly, as guilt appears to be an important maintaining mechanism in BED, future work should seek to clarify the source of guilt surrounding binge-eating episodes in order to inform intervention approaches and illuminate specific treatment targets.

Interestingly, although positive affect significantly decreased prior to binge-eating episodes, the hypothesized rebound effect (i.e., increases in positive affect) were not observed in the hours following binge episodes. Rather, levels of positive affect appeared to remain steady during this time. Although this finding is somewhat contrary to previous work demonstrating a uniform improvement in affect following eating disorder symptoms in AN and BN (Berg et al., 2013; Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), results may still be consistent with affect regulation models of eating pathology. That is, although positive affect did not substantially improve following the binge episode, the precipitous worsening of positive affect observed prior to binge episodes appears to have been halted at the point of the binge. It is therefore possible that binge eating in BED operates to stabilize declining positive affect which, along with post-binge reductions in negative affect, may reinforce the behavior.

The absence of a rebound effect following binge eating for positive affect also highlights potentially important differences in the patterns of affective experiences surrounding binge eating across different eating disorder diagnoses. Comparison of the estimated levels of affect states in the current study and those observed in similar studies using AN (Engel et al., 2013) and BN (Smyth et al., 2007) samples seems to indicate that individuals with BED may experience lower levels of negative affect preceding and during binge-eating episodes. This may reflect reduced affective lability among individuals with BED, which is consistent with some studies in this area (Brockmeyer et al., 2014), and/or suggest that less pronounced changes in affective states elicit binge-eating behavior in this population. Taken together, studies examining affect trajectories in the eating disorders suggest the potential for shared maintenance mechanisms across eating disorder diagnoses (e.g., reductions in negative affect following symptom engagement) as well as disorder-specific maintenance mechanisms (e.g., increases in positive affect in BN and AN, but not BED), which may have clinical importance. Future work explicitly comparing the trajectories of affect across eating disorder diagnoses is encouraged.

The current study has a number of important strengths. First, this study utilized a large sample of individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of DSM-5 BED, extending previous work which has been limited by the frequent use of small sample sizes and older diagnostic criteria (Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2011). By monitoring a large number of individuals with clinically-significant levels of binge eating over several days using EMA, the current study was able to capture a large number of binge-eating episodes and affect ratings. Further, the current sample size was similar to previous EMA studies examining affect trajectories in AN and BN (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007). In addition, the use of EMA and multilevel modeling of affect trajectories allowed for the examination of momentary changes in affect in the natural environment, as well as the temporal sequencing of those changes in relation to binge-eating episodes. This approach allowed us to examine the role of affective states in precipitating and reinforcing binge eating, and therefore provided a stringent test of affect regulation theory hypotheses. Finally, the examination of affect-binge processes in real time within real-world settings, served to reduce retrospective recall bias and increase the ecological validity of results.

Limitations of the study must also be acknowledged. First, DSM-5 criteria for BED define binge eating in part as the consumption of an objectively large amount of food in a discrete period of time accompanied by a sense of loss of control (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although this study utilized previously validated EMA methods of identifying binge-eating episodes that incorporate an assessment of both perceived overeating and loss of control (Wonderlich, Lavender, et al., 2015), data regarding the duration of the eating episode and the actual amount of food consumed during the episode were not collected. Therefore, it is unclear whether the episodes identified in the EMA protocol represent objective binge eating (i.e., loss of control over eating resulting in the consumption of an objectively large amount of food) or subjective binge eating (i.e., perceived loss of control over eating without the consumption of an objectively large amount of food). Importantly, evidence suggests that perceived loss of control during eating episodes, rather than the actual amount of the food consumed during the episode, represents the primary defining feature of binge-eating episodes (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2014), bolstering confidence in the validity of identified binge-eating episodes within the current study. Second, although previous work has employed abbreviated measures of momentary affect (e.g., PANAS) to reduce participant burden (Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), it is possible that this approach introduced measurement error by reducing construct coverage. Third, data from individuals identifying as male or female were combined in the current analyses. However, as previous work suggests gender differences in affective responses to binge-eating symptoms (Murray et al., 2017), future research using larger samples may seek to examine gender as a moderator of affect trajectories. Fourth, the current study utilized data from a randomized controlled treatment trial that was specifically powered to detect treatment effects. Although the sample size for the current study (n = 112) is similar to that of previous studies which were explicitly powered for trajectory analyses (e.g., n = 118; Engel et al., 2013), the absence of a priori power analyses in this study is a notable limitation, which may have impacted our ability to detect small effects. Fifth, although the EMA protocol utilized signal and interval contingent recordings, event contingent recordings were not utilized, likely reducing the number of recordings overall and, in particular, the number of affect ratings made shortly after binge-eating episodes. Future EMA studies seeking to examine proximal changes in affect following disordered eating behaviors are encouraged to implement event contingent recordings in order to optimize the number of available data points within this window of time. Finally, although the repeated assessment of examined variables via EMA allows for a clear establishment of temporal precedence (i.e., changes in affect precede engagement in maladaptive eating behaviors), this methodology precludes the ability to establish causality, and results must be interpreted accordingly.

Findings from the current study have important clinical implications. Results indicate that rising levels of negative affect (particularly guilt) and decreasing levels of positive affect are common antecedents to binge-eating episodes among individuals with BED. Consequently, clinicians may seek to increase patients’ awareness of these risky or vulnerable periods. Alternative coping or emotion regulation strategies appropriate to the individual’s predominant affective experience may be encouraged to reduce reliance on maladaptive binge-eating behavior. Similarly, technology-based ecological momentary interventions, such as just-in-time adaptive interventions may utilize patients’ momentary affect ratings to alert users to concerning shifts in affect, and suggest use of tailored emotion regulation skills during moments when patients are most vulnerable to engaging in binge eating. Although binge-eating episodes were followed by gradual improvements in some affective states (i.e., negative affect and guilt) and stabilization of other affective states (i.e., positive affect), it is interesting to note that affect ratings at the end of the 4-hour post-binge observation window did not appear to have returned to 4-hour pre-binge levels. That is, binge eating did not appear to fully alleviate unpleasant affective states. As individuals with binge-eating behavior frequently endorse strong expectancies that eating will alleviate negative affective states or induce positive affective states (Smith, Mason, Peterson, & Pearson, 2018; Smith, Simmons, Flory, Annus, & Hill, 2007), therapeutic discussion of these expectancies and behavioral experiments to support experiences of eating expectancy violation may be beneficial (Schyns, van den Akker, Roefs, Hilberath, & Jansen, 2018).

Overall, results from the current study demonstrate worsening affect prior to binge-eating episodes, and subsequent stabilizing or improvement in affect following binge-eating episodes among men and women with BED. Findings from the current study are expected to be generalizable to the broader population of treatment-seeking individuals with DSM-5 BED. Further, given that prior work has demonstrated increases in negative affect preceding binge-eating episodes and reductions in negative affect following such episodes in AN, BN, and obesity (Berg et al., 2015; Engel et al., 2013; Smyth et al., 2007), this pattern appears remarkably robust, and is therefore expected to generalize to the larger population of individuals with problematic binge-eating behavior. Findings lend support to affect regulation models of disordered eating, suggesting that binge eating may be precipitated and reinforced through momentary changes in affective states. Therefore, treatment approaches that seek to address maladaptive affect-behavior relationships in BED may demonstrate success in this population, though continued research in this area is needed.

Supplementary Material

General Scientific Summary:

This study indicates that, among individuals with binge-eating disorder, binge-eating episodes are generally preceded by worsening affect and followed by improvements in affect. These findings are consistent with affect regulation models of eating pathology and suggest that binge-eating episodes may be maintained through a process of negative reinforcement.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant numbers R34 MH099040–01A1 and T32 MH082761).

Footnotes

Findings from the current study were presented as a poster during the Eating Disorder Research Society 25th annual meeting (Chicago, 2019).

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for this study was obtained from the University of Minnesota (IRB Study #: R34 MH099040) and Sanford Research (IRB Study #: 03-13-123).

DSM-IV criteria were used to assess comorbid psychopathology as the SCID for DSM-5 was not available at the time of participant enrollment and assessment.

Analyses examining the potential moderating role of weight and shape overvaluation (Grilo, White, & Masheb, 2012) on affect trajectories were also conducted, and results are available as Supplemental Material. The FDR procedures take these additional analyses into account.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 57, 289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Cao L, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, & … Wonderlich SA (2017). Negative affect and binge eating: Reconciling differences between two analytic approaches in ecological momentary assessment research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50, 1222–1230. doi: 10.1002/eat.22770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich, & Peterson CB (2015). Negative affect prior to and following overeating-only, loss of control eating-only, and binge eating episodes in obese adults. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48, 641–653. doi: 10.1002/eat.22401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Crosby RD, Cao L, Peterson CB, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, & Wonderlich SA (2013). Facets of negative affect prior to and following binge-only, purge-only, and binge/purge events in women with bulimia nervosa. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 111–118. doi: 10.1037/a0029703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer T, Skunde M, Wu M, Bresslein E, Rudofsky G, Herzog W, & Friederich HC, (2014). Difficulties in emotion regulation across the spectrum of eating disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 55, 565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, & … Gordon KH (2013). The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: Evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 709–719. doi: 10.1037/a0034010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG (2008). Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG (2013). Overcoming binge eating: The proven program to learn why you binge and how you can stop (2nd ed). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, & Cooper Z (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination In Fairburn CG & Wilson GT (), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment ( 317–360). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JB (1995). Structured clinical interview for the DSM–IV axis I disorders—patient edition (SCID–I/P, version 2). New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Breithaupt L, Wonderlich J, Westwater ML, Crosby RD, Engel SG, … Wonderlich S (2017). Impact of the neural correlates of stress and cue reactivity on stress related binge eating in the natural environment. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 92, 15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimmons CEE, Ciao AC, Accurso EC, Pisetsky EM, Peterson CB, Byrne CE, & Le Grange D (2014). Subjective and objective binge eating in relation to eating disorder symptomatology, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem among treatment-seeking adolescents with bulimia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 22, 230–236. doi: 10.1002/erv.2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Crosby RD, Cao L, Engel SG, Durkin N, Beach HM, … Peterson CB (2014). Ecological momentary assessment of eating episodes in obese adults. Psychosomatic Medicine, 76, 747–752. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA, & Masheb RM (2012). Significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in an ethnically diverse sample of obese patients with binge-eating disorder in primary care settings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA, & Masheb RM (2009). DSM-IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42, 228–234. doi: 10.1002/eat.20599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, & Keel PK (2011). Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 660–681. doi: 10.1037/a0023660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, & Baumeister RF (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D & Gibbons RD (1997). Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods, 2, 64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D & Gibbons RD (2006). Longitudinal Data Analysis. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr., & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarascio AS, Parker MN, Lagacey MA, & Godfrey KM (2018). Just-in-time adaptive interventions: A novel approach for enhancing skill utilization and acquisition in cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 826–830. doi: 10.1002/eat.22924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher K (1992). Assessing subjective well-being in the old-old. The PANAS as a measure of orthogonal dimensions of positive and negative affect. Research on Aging, 14, 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Gordon KH, Kaye WH, & Mitchell JE (2015). Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, & Giel KE (2015). Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity: A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 49, 125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J (2018). Rates of abstinence following psychological or behavioral treatments for binge-eating disorder: Meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 785–797. doi: 10.1002/eat.22897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JH (2014). Handbook of Biological Statistics (3rd ed). Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno S, Warren CS, Rodríguez S, Fernandez MC, & Cepeda-Benito A (2009). Food cravings discriminate between anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Implications for “success” versus “failure” in dietary restriction. Appetite, 52, 588.e. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S, Calzo JP, Brown TA, Mitchison D, … Mond JM (2017). The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Engel SG, Crosby RD, Strauman T, Smith TL, Klein M, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ, & Wonderlich SA (2020). Integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) compared to guided self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBTgsh) for the treatment of binge-eating disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Telch CF, & Chen EY (2009). Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schyns G, van den Akker K, Roefs A, Hilberath R, & Jansen A (2018). What works better? Food cue exposure aiming at the habituation of eating desires or food cue exposure aiming at the violation of overeating expectancies? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 102, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Mason TB, Juarascio A, Schaefer LM, Crosby RD, Engel SG, & Wonderlich SA (2019). Moving beyond self-report data collection in the natural environment: A review of the past and future directions for ambulatory assessment in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1002/eat.23124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Mason TB, Peterson CB, & Pearson CM (2018). Relationships between eating disorder-specific and transdiagnostic risk factors for binge eating: An integrative moderated mediation model of emotion regulation, anticipatory reward, and expectancy. Eating Behaviors, 31, 131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Simmons JR, Flory K, Annus AM, & Hill KK (2007). Thinness and eating expectancies predict subsequent binge-eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116, 188–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, & Engel SG (2007). Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, & Shiffman S (1994). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavorial medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form. Ames: The University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, & Reis HT (1991). Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality, 59, 339–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00252.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, MacKenzie KR, Welch RR, Ayres VE, & Weissman MM (2000). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Group. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich JA, Breithaupt LE, Crosby RD, Thompson JC, Engel SG, & Fischer S (2017). The relation between craving and binge eating: Integrating neuroimaging and ecological momentary assessment. Appetite, 117, 294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich JA, Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Engel SG, … Crosby RD (2015). Examining convergence of retrospective and ecological momentary assessment measures of negative affect and eating disorder behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48, 305–311. https://doiorg.ezproxylr.med.und.edu/10.1002/eat.22352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, & Crow SJ (2015). Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy for bulimia nervosa: A treatment manual. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.