Abstract

Background:

No large-scale epidemiological survey of adolescents in the US has assessed the association between lifetime history of concussion, propensity toward sensation-seeking, and recent substance use.

Methods:

This study assesses the association between lifetime history of diagnosed concussions, sensation-seeking, and recent substance use (i.e., cigarette use, binge drinking, marijuana use, illicit drug use, and nonmedical prescription drug use) using the 2016 and 2017 Monitoring the Future study of 25,408 8th, 10th, and 12th graders.

Results:

Lifetime diagnosis of concussion was associated with greater odds of past 30-day/two-week substance use. Adolescents who indicated multiple diagnosed concussions (versus none) had two times greater odds of all types of recent substance use, after adjusting for potential confounding factors. Adolescents indicating multiple diagnosed concussions also had higher adjusted odds of cigarette use, binge drinking, and marijuana use) when compared to adolescents who only indicated one diagnosed concussion. Accounting for adolescents’ propensity toward sensation-seeking did not significantly change the association between substance use and multiple diagnosed concussions.

Conclusions:

This study provides needed epidemiological data regarding concussion and substance use among US adolescents. Exposure to a single diagnosed concussion is associated with a modest increase in the risk of substance use and this association increases with the accumulation of multiple diagnosed concussions. These associations hold when controlling for sensation-seeking. Substance use prevention efforts should be directed toward adolescents who have a history of multiple concussions.

Keywords: Concussion, Substance Use, Adolescents

INTRODCUTION

Concussion, or mild traumatic brain injury, is a serious public health issue facing adolescents in the United States1-4 and has been associated with substance use.5-8 According to a recent US-national survey of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, roughly 20% of adolescents indicated having at least one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime, with 5.5% reporting multiple diagnosed concussions.4 This finding is consistent with a regional Canadian epidemiological survey of youth in which 20% of 7th to 12th graders indicated a history of concussion (defined as being unconscious for at least 5 minutes or hospitalized overnight).5 Research based on this Canadian regional survey has also found that adolescents with a history of concussion were more than twice as likely as youth with no concussion to use alcohol, tobacco, or illicit drugs, and to screen positively for potential substance use disorder (based on the CRAFFT instrument).7 Moreover, adult studies have shown that more than a third of adults who suffered a concussion were intoxicated with alcohol at the time of the incident, and nearly a third of those who reported a concussion had a previous history of illicit drug use.9-12 As 1 in 5 adolescents are affected by concussion, it is important to better understand the associated risks of substance use in this age group.

While it is difficult to discern the directionality of the relationship between concussion and substance use from the current literature,9 these studies suggest that one potential mechanism in both concussion and substance use is a higher propensity toward risk-taking, including sensation-seeking. Indeed, higher levels of sensation-seeking have been found to be associated with both substance use13-17 and with concussion.18-20 Given the clear overlap that sensation seeking has with both of these injuries/behaviors, it is necessary to account for adolescents’ levels of sensation-seeking when assessing the association between concussion and substance use within the adolescent population.

The purpose of this study is twofold. Currently no large-scale epidemiological survey of US adolescents has assessed the association between lifetime history of concussion and recent substance use. Thus our first purpose is to address this gap using US-national surveys of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students in the 2016 and 2017 Monitoring the Future study (MTF) to assess the association between lifetime history of diagnosed concussions and recent (past 30-day and 2-week) substance use. Our second purpose is to examine the potential confounding and moderating effects of sensation-seeking on the association between concussion and recent substance use in this population.

METHODS

Study Design

The present study uses cross-sectional data from MTF for 2016 and 2017.21 Based on a three-stage sampling procedure, MTF surveys nationally representative samples of approximately 15,000 US 12th graders and approximately 30,000 US 8th and 10th graders annually. Response rates for 2016 and 2017 were 89%, 87%, and 83% for the 8th, 10th, and 12th grade samples, respectively. The institutional review board at the University of Michigan approved this study. A waiver of informed consent was sent to parents providing them a means to decline their child’s participation if necessary. Project design and sampling methods are described in greater detail elsewhere.21-22

Sample

A measure of lifetime prevalence of concussions was included on one-third of 8th and 10th grade and one-sixth of 12th grade questionnaire forms distributed randomly within data collection forums in 2016 and 2017. The analytic sample included 25,408 respondents for the three grades combined (which included 4,359 12th grade respondents). Refer to Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Table 1:

Sociodemographic characteristics for the full (8th, 10th, and 12th grade) and 12th grade sample

| Total1,3 % (n) |

12th graders2,3 % (n) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | n = (25408) | n = (4359) | ||

| Male (reference) | 49.5% | (11979) | 48.9% | (2012) |

| Female | 50.4% | (12043) | 51.0% | (2071) |

| Race | ||||

| White (reference) | 44.6% | (11421) | 48.5% | (2204) |

| Black | 12.3% | (3028) | 13.3% | (546) |

| Hispanic | 21.1% | (5323) | 18.3% | (759) |

| Other | 22.0% | (5636) | 19.9% | (850) |

| Parental Level of Education | ||||

| Both parents do not have a college degree (reference) | 43.4% | (9633) | 49.8% | (1871) |

| At least one parent has a college degree or higher | 56.6% | (12747) | 50.2% | (2129) |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Lives in a large MSA (reference) | 32.0% | (8681) | 33.3% | (1654) |

| Lives in a MSA | 48.8% | (11645) | 46.6% | (1909) |

| Lives in a non-MSA | 19.2% | (5082) | 20.1% | (796) |

| Region | ||||

| Lives in the Northeast (reference) | 17.2% | (4752) | 15.9% | (821) |

| Lives in the Midwest | 21.7% | (5622) | 21.4% | (966) |

| Lives in the South | 37.5% | (8872) | 39.5% | (1564) |

| Lives in the West | 23.6% | (6162) | 23.2% | (1008) |

| Grade | ||||

| 8th (reference) | 44.2% | (11232) | -- | -- |

| 10th | 38.7% | (9817) | -- | -- |

| 12th | 17.1% | (4359) | -- | -- |

| Truancy | ||||

| Did not cut class in the past four weeks (reference) | 85.2% | (19472) | 69.3% | (2757) |

| Cut class at least once in the past four weeks | 14.8% | (3384) | 30.7% | (1174) |

| Average Grade in School | ||||

| Average grade of a B- or higher (reference) | 81.1% | (19406) | 86.3% | (3553) |

| Average grade of a C+ or lower | 18.9% | (4564) | 13.7% | (515) |

| Nights Out per Week Without Parent | ||||

| Goes out at night 2 nights a week or less (reference) | 71.9% | (16957) | 63.6% | (2559) |

| Goes out at night 3 nights a week or more | 28.1% | (6588) | 36.4% | (1440) |

| Participation in Competitive Sport (past-year) | ||||

| Does not participate in sport (reference) | 25.4% | (6116) | 34.4% | (1225) |

| Participates in at least one sport | 74.6% | (17881) | 65.6% | (2444) |

% = percent; n = sample size; MSA = Metropolitan Statistical Area

All percentages were estimated using custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample and to adjust for the different sample sizes for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. Unweighted sample sizes are provided.

All percentages were estimated using custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample. Unweighted sample sizes are provided.

The percent of missing data from each item is the following: sex 5.5% (12th grade sample 6.3%), race 0.0% (12th grade sample 0.0%), parental level of education 11.9% (12th grade sample 8.2%), urbanicity 0.0% (12th grade sample 0.0%), region 0.0% (12th grade sample 0.0%), grade 0.0% (12th grade sample 0.0%), truancy 10.0% (12th grade sample 9.8%), average grade in school 5.7% (12th grade sample 6.7%), nights out per week 7.3% (12th grade sample 8.3%), participation in sport 5.6% (12th grade sample 15.8%).

Measures

Lifetime diagnosis of concussion4 was measured with a single item that asked respondents the following: “Have you ever had a head injury that was diagnosed as a concussion?” Response options included “No”, “Yes, once”, and “Yes, more than once.” For the analysis, three variables were constructed to assess lifetime reports of any concussion (i.e., “Yes, once” and “Yes, more than once”), one concussion (i.e., “Yes once”), and multiple concussions (i.e., “Yes, more than once”).

Consistent with past MTF studies,14,17 propensity toward sensation-seeking was measured with two items that asked respondents “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements…(1) I get a real kick out of doing things that are a little dangerous, (2) I like to test myself every now and then by doing something a little risky.” The five response options ranged from “disagree” to “agree.” A three-category mutually exclusive variable was constructed by taking the mean score of the two items and included the following groups: (1) low sensation-seeking (i.e., a score between 1.00 and 2.00), moderate sensation-seeking (i.e., a score between 2.01 and 3.50), and high sensation-seeking (i.e., a score between 3.51 and 5.00). The constructed measure has an alpha score that ranges between .81 and .82 among 12th graders across the forms that provide these two items. Only 12th grade respondents received both sensation-seeking and concussion items; thus analyses concerning sensation-seeking include only the national samples of 12th graders.

Past 30-day/past two-week substance use21-23 asked about substance use “during the past 30 days” on all items except binge drinking, which asked about “the past two weeks”: past 30-day cigarette use (i.e., ‘How frequently have you smoked cigarettes …?’), past two-week binge drinking (i.e., ‘How many times have you had five or more drinks in a row …?’), past 30-day marijuana use (i.e., ‘On how many occasions have you used marijuana or hashish …?’), past 30-day nonmedical use of prescription drugs (i.e., ‘On how many occasions have you taken [amphetamines, sedatives, tranquilizers] on your own -- that is, without a doctor telling you to take them …?’), and past 30-day illicit substance use other than marijuana (i.e., ‘On how many occasions have you used [cocaine, crack, LSD, hallucinogens, and heroin] …?’). Separate questions were asked for each of the nonmedical prescription drugs (i.e., amphetamines, sedatives, and tranquilizers) and illicit substances other than marijuana (i.e., cocaine, crack, LSD, hallucinogens, and heroin). For analytic purposes, overall measures (i.e., indicated at least one of the items) of nonmedical prescription drug use and illicit drug use were assessed. Finally, the response categories for the questions assessing past 30-day/two-week substance use were recoded and treated as dichotomous variables (i.e., no use = 0, and any use = 1).

Control variables accounted for potentially confounding factors known to be associated with substance use among adolescents,21-25 including sex, grade level, race, parental level of education, truancy, school performance, involvement in sports, number of nights respondent goes out at night without a parent during a typical week, urbanicity, and geographic location (see Table 1).

Analysis

To address our first purpose, descriptive statistics, odds ratios (OR), and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) were used to assess the association between lifetime prevalence of diagnosed concussions and past 30-day/two-week substance use for the entire sample of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. Interaction effects between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and each of the sociodemographic items were tested (Table 1). To address our second purpose, the above association was tested in the 12th grade sample while accounting for sensation-seeking as a potentially confounding or mediating factor, and controlling for sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, we tested interaction effects between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and respondents’ propensity toward sensation-seeking.

STATA 15.0 was used to conduct analyses (Version 15.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas) and binary logistic regression models were used to estimate ORs, AORs and 95% confidence intervals. All analyses applied custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample and adjust for the different sample sizes for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. Due to missing data on some of the items, analyses were conducted using both listwise deletion and multiple imputation.26 Both sets of analyses yielded similar results; analyses using listwise deletion were presented for ease of reproducibility. Finally, sensitivity analyses compared past-year to past 30-day substance use for marijuana, nonmedical prescription drugs, and illicit drugs other than marijuana; again analyses yielded similar results.

RESULTS

Lifetime diagnosis of concussion

Tables 1 and 2 provide descriptive statistics for sociodemographic characteristics, lifetime prevalence of diagnosed concussions, propensity toward sensation-seeking, and past 30-day/two-week substance use for the combined (8th, 10th, and 12th) sample and the 12th grade sample. For the combined sample, 18.4% of respondents reported at least one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime; 13.4% reported only one diagnosed concussion, while 5.0% reported multiple diagnosed concussions during their lifetime. For the 12th grade sample, 14.7% reported only one diagnosed concussion while 5.6% reported multiple diagnosed concussions during their lifetime.

Table 2:

Descriptives for key indicator and outcome variables.

| Total1,3 % (n) |

12th graders2,3 % (n) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Indicator Variables | n = 25408 | n = 4359 | ||

| Diagnosed Concussion (lifetime) | ||||

| No Diagnosed Concussion (reference) | 81.6% | (19735) | 79.4% | (2956) |

| One Diagnosed Concussion | 13.4% | (3322) | 14.7% | (549) |

| Multiple Diagnosed Concussions | 5.0% | (1224) | 5.9% | (241) |

| Propensity Toward Sensation Seeking | ||||

| Low Sensation Seeking (reference) | -- | -- | 24.0% | (927) |

| Moderate Sensation Seeking | -- | -- | 40.3% | (1473) |

| High Risk Sensation Seeking | -- | -- | 35.7% | (1331) |

| Substance Use Outcomes | ||||

| Binge Drinking | ||||

| No Past Two-Week Binge Drinking | 91.9% | (21269) | 83.2% | (3251) |

| Past Two-Week Binge Drinking | 8.1% | (2038) | 16.8% | (740) |

| Cigarette Use | ||||

| No Past 30-Day Cigarette Use | 95.7% | (23317) | 90.6% | (3816) |

| Past 30-Day Cigarette Use | 4.3% | (1098) | 9.4% | (390) |

| Marijuana Use | ||||

| No Past 30-Day Marijuana Use | 88.1% | (21176) | 77.1% | (3166) |

| Past 30-Day Marijuana Use | 11.9% | (2981) | 22.9% | (937) |

| Illicit Drug Use | ||||

| No Past 30-Day Illicit Drug Use | 98.7% | (24310) | 97.1% | (4109) |

| Past 30-Day Illicit Drug Use | 1.2% | (335) | 2.9% | (127) |

| Nonmedical Rx Drug Use | ||||

| No Past 30-Day Nonmedical Rx Drug Use | 96.1% | (23486) | 95.5% | (4005) |

| Past 30-Day Nonmedical Rx Drug Use | 3.9% | (963) | 4.5% | (183) |

% = percent; n = sample size; Rx = prescription. Sample sizes vary due to missing data.

All percentages were estimated using custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample and to adjust for the different sample sizes for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. Unweighted sample sizes are provided.

All percentages were estimated using custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample. Unweighted sample sizes are provided.

The percent of missing data from each item is the following: concussion 4.4% (12th grade sample 14.1%), sensation seeking 14.4% (12th grade sample only), binge drinking 8.3% (12th grade sample 8.4%), cigarette use 3.9% (12th grade sample 3.5%), marijuana use 4.9% (12th grade sample 5.9%), illicit drug use 3.0% (12th grade sample 2.8%), nonmedical prescription drug use 3.8% (12th grade sample 3.9%).

Association between concussion and substance use (combined 8th, 10th, and 12th grade sample)

Table 3 shows the association between lifetime prevalence of diagnosed concussions and past 30-day/two-week substance use for the combined sample. As shown, respondents who reported one or multiple diagnosed concussions had significantly higher odds of binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use other than marijuana when compared to their peers who had never reported a diagnosed concussion. Additionally, those reporting multiple diagnosed concussions had higher odds of binge drinking, cigarette use, and marijuana use when compared to respondents who had reported only one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime. No statistically significant differences between respondents reporting multiple diagnosed concussions and those who reported only one diagnosed concussion were found for illicit drug use other than marijuana and nonmedical prescription drug use.

Table 3:

Assessing the association between lifetime diagnosed concussion and substance use (8th, 10th, and 12th grade sample).

| Binge Drinking | Cigarette Use | Marijuana Use | Illicit Drug Use | Nonmedical Rx Drug Use | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 11 | Model 21 | Model 31 | Model 41 | Model 51 | |||||||||||

| Diagnosed Concussion (lifetime) | % | OR | 95% CI | % | OR | 95% CI | % | OR | 95% CI | % | OR | 95% CI | % | OR | 95% CI |

| No Diagnosed Concussion (reference) | 6.7% | Reference | 3.6% | Reference | 10.4% | Reference | 0.9% | Reference | 3.0% | Reference | |||||

| One Diagnosed Concussion | 11.6% | 1.83*** | (1.58, 2.11)5 | 6.0% | 1.72*** | (1.41, 2.10)5 | 14.9% | 1.50*** | (1.31, 1.72)5 | 2.2% | 2.61*** | (1.94, 3.49)3 | 6.1% | 2.08*** | (1.71, 2.54)5 |

| Multiple Diagnosed Concussions | 18.0% | 3.05*** | (2.58, 3.60)5 | 9.9% | 2.97*** | (2.34, 3.78)5 | 22.4% | 2.48*** | (2.09, 2.93)5 | 3.5% | 4.14*** | (2.79, 6.15)3 | 10.5% | 3.73*** | (2.90, 4.80)5 |

| n = 22,525 | n = 23,924 | n = 23,357 | n = 23,807 | n = 23,640 | |||||||||||

| Model 62 | Model 72 | Model 82 | Model 92 | Model 102 | |||||||||||

| Diagnosed Concussion (lifetime) | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| No Diagnosed Concussion (reference) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| One Diagnosed Concussion | 1.45*** | (1.22, 1.72)4 | 1.40** | (1.10, 1.77)3 | 1.40*** | (1.22, 1.62)4 | 1.81*** | (1.27, 2.58) | 1.98*** | (1.57, 2.49) | |||||

| Multiple Diagnosed Concussions | 2.07*** | (1.66, 2.58)4 | 2.12*** | (1.54, 2.91)3 | 1.91*** | (1.54, 2.37)4 | 2.00** | (1.21, 3.31) | 2.72*** | (1.93, 3.82) | |||||

| n = 17,493 | n = 18,204 | n = 18,171 | n = 18,439 | n = 18,396 | |||||||||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001; % = percent; AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. Sample sizes vary due to missing data. All analyses (Models 1 through 10) used custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample and to adjust for the different sample sizes for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders.

Models 1 through 5 only assess the bivariate association between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and past two week/30-day substance use (no control variables were included).

Models 6 through 10 assess the association between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and past two week/30-day substance use when controlling for sex, race, parental level of education, urbanicity (e.g., residence in an MSA), region, grade, truancy, average grade, average nights out per week, and participation in competitive sports (see Table 1 for more details on these control variables).

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .05 alpha level.

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .01 alpha level.

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .001 alpha level.

Only one notable significant interaction effect was found between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and sociodemographic characteristics; namely, females with one diagnosed concussion (i.e., female X one diagnosed concussion: AOR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.15, 3.17) reached statistical significance with respect to nonmedical prescription drug use. This significant interaction effect suggests that the association between past 30-day nonmedical prescription drug use and reporting one diagnosed concussion is stronger for females than males (results are based on stratifying by sex: male AOR = 1.34, 95% CI = .909, 1.99; female AOR = 2.72, 95% CI = 2.02, 3.76).

Association between concussion and substance use when accounting for propensity toward sensation-seeking (12th grade sample)

Sensation-seeking as a potential confound.

Table 4 provides the results assessing the association between lifetime diagnosis of concussions and past 30-day/two-week substance use in the 12th grade sample. Models 11 through 15 show the results assessing the association controlling for sociodemographic characteristics but not accounting for propensity toward sensation-seeking. Consistent with the combined sample, 12th grade respondents who indicated multiple diagnosed concussions had higher odds of binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, and nonmedical prescription drug use when compared to respondents who reported no diagnosed concussion. Those who reported only one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime had higher odds of binge drinking and marijuana use when compared to peers who reported no diagnosed concussion.

Table 4:

Assessing the association between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and substance use when accounting for sensation-seeking (12th grade sample)

| Binge Drinking | Cigarette Use | Marijuana Use | Illicit Drug Use | Nonmedical Rx Drug Use | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 111 | Model 121 | Model 131 | Model 141 | Model 151 | |||||||||||

| Diagnosed Concussion (lifetime) | % | AOR | 95% CI | % | AOR | 95% CI | % | AOR | 95% CI | % | AOR | 95% CI | % | AOR | 95% CI |

| No Concussion (reference) | 14.6% | Reference | 8.5% | Reference | 20.6% | Reference | 2.2% | Reference | 3.6% | Reference | |||||

| One Diagnosed Concussion | 22.2% | 1.83* | (1.03, 1.86) | 10.0% | 1.05 | (0.68, 1.61)3 | 26.6% | 1.47** | (1.13, 1.92) | 4.3% | 1.60 | (0.89, 2.87) | 5.3% | 1.47 | (0.82, 2.64)3 |

| Multiple Diagnosed Concussions | 31.3% | 1.93*** | (1.31, 2.83) | 17.1% | 1.99** | (1.25, 3.17)3 | 35.0% | 1.79** | (1.25, 2.57) | 4.1% | 1.46 | (0.58, 3.71) | 11.8% | 3.07*** | (1.65, 5.71)3 |

| n = 3,000 | n = 3,125 | n = 3,079 | n = 3,156 | n = 3,147 | |||||||||||

| Model 162 | Model 172 | Model 182 | Model 192 | Model 202 | |||||||||||

| Diagnosed Concussion (lifetime) | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |||||

| No Concussion (reference) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| One Diagnosed Concussion | 1.35 | (1.00, 1.82) | 1.04 | (0.66, 1.62)3 | 1.43** | (1.09, 1.88) | 1.66 | (0.91, 3.01) | 1.46 | (0.81, 2.60)3 | |||||

| Multiple Diagnosed Concussions | 1.73** | (1.14, 2.62) | 1.85** | (1.16, 2.95)3 | 1.62* | (1.12, 2.35) | 1.54 | (0.59, 4.03) | 2.92*** | (1.56, 5.45)3 | |||||

| Propensity Toward Sensation Seeking | |||||||||||||||

| Low Sensation Seeking (reference) | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| Moderate Sensation Seeking | 1.67*** | (1.17, 2.39) | 1.05 | (0.70, 1.59) | 1.66*** | (1.23, 2.24) | 0.74 | (0.34, 1.59) | 1.77 | (0.98, 3.20) | |||||

| High Risk Sensation Seeking | 2.96*** | (2.08, 4.22) | 1.94*** | (1.30, 2.90) | 2.87*** | (2.13, 3.88) | 1.03 | (0.55, 1.95) | 2.18* | (1.18, 4.01) | |||||

| n = 2,980 | n = 3,105 | n = 3,059 | n = 3,136 | n = 3,127 | |||||||||||

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001; % = percent; AOR = Adjusted Odds Ratio. Sample sizes vary due to missing data. All analyses (Models 11 through 20) used custom weights provided by MTF to account for the probability of selection into the sample.

Models 11 through 15 assess the association between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and past two week/30-day substance use when controlling for sex, race, parental level of education, urbanicity (e.g., residence in an MSA), region, truancy, average grade, average nights out per week, and participation in competitive sports (see Table 1 for more details on these control variables). These models did not include the variables assessing propensity toward risk taking.

Models 16 through 20 assess the association between lifetime diagnosis of concussion and past two week/30-day substance use when controlling for sex, race, parental level of education, urbanicity (e.g., residence in an MSA), region, truancy, average grade, average nights out per week, participation in competitive sports (see Table 1 for more details on these control variables), and propensity toward risk taking.

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .05 alpha level.

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .01 alpha level.

Differences between one diagnosed concussion and multiple diagnosed concussions are significant at the .001 alpha level.

In the 12th grade sample, respondents with a high propensity toward sensation-seeking had higher odds of indicating at least one diagnosed concussion (OR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.27, 2.06) and multiple concussions (OR = 2.65, 95% CI = 1.68, 4.19) when compared to peers with a low propensity toward sensation-seeking; those who had a moderate propensity toward sensation-seeking had similar odds of reporting at least one, only one, or multiple diagnosed concussions during their lifetime when compared to their peers who had a low propensity toward sensation-seeking (results not tabled).

The results that include sensation-seeking for 12th graders are provided in models 16 through 20. Those who reported just one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime had higher odds of marijuana use when compared to respondents who never indicated having a diagnosed concussion (the association with binge drinking was no longer statistically significant, refer to models 11 and 16). For those who reported multiple concussions, the inclusion of sensation-seeking did not alter the findings, as reflected in comparing corresponding AORs in models 11 through 15 and 16 through 20. Thus, controlling for sensation-seeking, multiple concussions were significantly associated with binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, and nonmedical prescription drug use. Respondents with high propensity, compared to those with low propensity, toward sensation-seeking had higher odds of binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, and nonmedical prescription drug use.

Sensation-seeking as moderator.

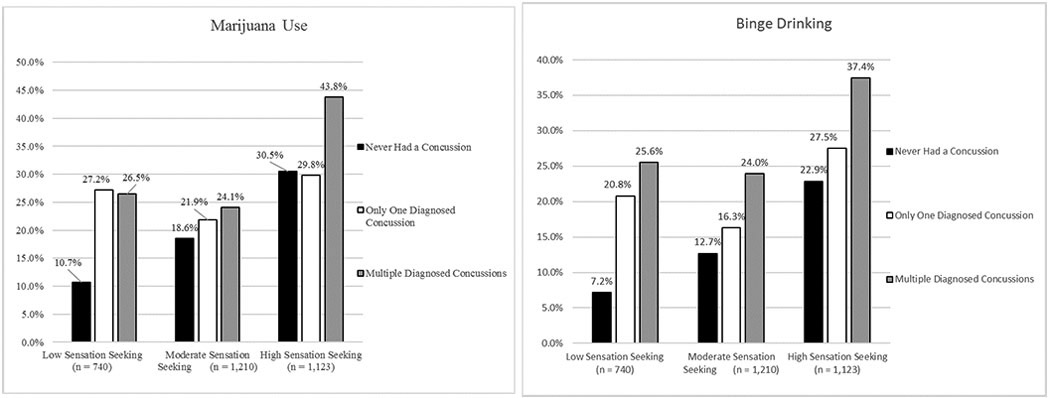

The interaction effects between lifetime diagnosis of concussions and propensity toward sensation-seeking produced several statistically significant results (interaction effects not tabled; stratified results presented in Figure 1). With respect to binge drinking, significant interaction effects were found for moderate sensation-seeking by multiple diagnosed concussions (AOR = .262, 95% CI = .074, .926) and high sensation-seeking by multiple diagnosed concussions (AOR = .245, 95% CI = .066, .909). Regarding marijuana use, significant interaction effects were found for moderate sensation-seeking by one diagnosed concussion (AOR = .354, 95% CI = .166, .754), high sensation-seeking by one diagnosed concussion (AOR = .361, 95% CI = .181, .719), and moderate sensation-seeking by multiple diagnosed concussions (AOR = .236, 95% CI = .076, .727). These results show that the association between diagnosed concussions and substance use (i.e., binge drinking and marijuana use) is stronger for respondents with a low propensity toward sensation-seeking than for those with medium or high sensation-seeking (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sensation-seeking as a moderator for marijuana use and binge drinking.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 1 in 5 US teens between the 8th and 12th grade report at least one diagnosed concussion during their lifetime, with 5.0% reporting multiple concussions (lifetime prevalence for diagnosed concussion was consistent across the 2016 and 2017 samples).4 Consistent with prior research on adolecents,5-8 we found substantial associations between lifetime prevalence of diagnosed concussions and past 30-day/two-week substance use in the sample of 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. In particular, the odds of engaging in binge drinking, cigarette use, marijuana use, illicit drug use, and nonmedical prescription drug use was highest among adolescents who reported multiple diagnosed concussions during their lifetime, highlighting the potential link between substance use and exposure to multiple head injuries. While the findings also show evidence of an association between single incidents of concussion and substance use, this association was relatively modest.

In addition, 12th graders who have a high propensity for sensation-seeking were more likely to report any diagnosed concussion during their lifetime. Interestingly, when the analytic models accounted for adolescents’ propensity toward sensation seeking, the positive association between diagnosed concussions and substance use was relatively similar to the analytic models that did not control for sensation-seeking; this was particularly evident for the association between multiple diagnosed concussions and substance use. This indicates that, although sensation-seeking is related to both concussion and substance use, it does not largely account for the association between concussion and substance use and warrants further study.

Regarding the potential moderating effect of sensation-seeking, the interaction effect between sensation-seeking and diagnosed concussion revealed that the association between concussion and substance use (i.e., binge drinking and marijuana use) was strongest among adolescents who had a low propensity toward sensation-seeking. For instance, the odds of marijuana use were four times (with one concussion) and eight times (with multiple concussions) higher among previously concussed low-sensation-seeking adolescents, while the odds of marijuana use were roughly one-and-a-half times higher among concussed high-sensation-seeking adolescents (see Figure 1). These findings suggest that while adolescents who have been diagnosed with a concussion (particularly those with multiple concussions) are at greater risk of substance use and vice versa, it is the group of adolescents who are the least prone to engage in risky behaviors whose concussion history and substance use are most strongly associated. This may suggest that these injuries can impact certain executive functions, like impulse control, which can lead to a greater susceptibility to engage in substance use in low-risk populations of adolescents. Problematically, many of these low risk youth may be at an increased risk of sustaining head injuries due to the fact that they are also more likely to participate in multiple sports.4,27

The analyses clearly demonstrate that concussion, sensation-seeking, and substance use are linked; however, the cross-sectional design does not permit assessment of the causal pattern that tie these factors together. Despite this limitation in the study design, the analyses do reveal an independent association between concussion and substance use when risk-taking or sensation-seeking behavior is accounted for in the models. This finding argues against the possibility that sensation-seeking is driving a spurious association between concussion and substance use. Additionally, these analyses highlight that head injuries and substance use may impact certain segments of the adolescent population more negatively. In particular, adolescents who are least likely to either engage in substance use or sustain a concussion (based on having low propensity toward sensation-seeking) demonstrate the greatest behavioral disturbance as it relates to the impact of concussion on risky drinking and marijuana use.

Several limitations should be noted. First, the measure of diagnosed concussion is based on self-report, and thus given to potential over- or under-estimation. The prevalence that we report is consistent with what other studies have reported.5 Furthermore, using self-report, rather than ER or medically reported concussion permits consideration of national and subgroup estimates regarding adolescent head injury. Second, the study is cross-sectional, precluding causal interpretation of the association between concussion, propensity toward sensation-seeking, and substance use. It is likely that there is some reciprocal relations among concussion and substance use. Accordingly, future studies would benefit from using large-scale longitudinal data to investigate the short- and long-term impact of concussion on substance use as adolescents transition into young adulthood. Third, the measures for concussion and substance use were temporally incongruent (i.e., lifetime versus past 30-day/two-week) indicating that the reported associations between the two may not be directly causal and attributable in part to other unmeasured factors; however, the associations held after controlling for sensation seeking and numerous sociodemographic and behavior characteristics. Furthermore, it should be noted that the analyses produced similar results using lifetime and past-year measures of substance use. Finally, the measure assessing lifetime prevalence of concussion may be capturing more mild or moderate (e.g., the diagnosis may have not come within a healthcare setting) forms of head injuries and may produce higher rates than what is found from emergency department data or from questions asking about ‘significant’ head injuries.4,28-29 Despite these limitations, the study supplies nationally representative findings for adolescents in the US and brings needed epidemiological data to track the negative correlates of concussions during adolescence.

In summary, the national results are consistent with regional studies assessing the association between head injuries and substance use among adolescents.5-8 We advance this literature by showing that the associations hold even when controlling for sensation-seeking, a potentially confounding factor, and by finding substantial differences in substance use between adolescents reporting only one diagnosed concussion and those reporting two or more diagnosed concussions during their lifetime. In particular, the positive association between substance use and concussion increases with the accumulation of brain injuries during adolescence. The results suggest that exposure to a single diagnosed concussion is associated with a modest increase in the risk of substance use. Substance abuse prevention efforts should be directed toward adolescents who have experienced multiple head injuries given that this subpopulation is more likely to experience cognitive impairments that influence riskier forms of behavior.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The development of this manuscript was supported by research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse [L40DA042452, R01DA031160, R01DA036541, and R01DA001411], National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [K23HD078502], and National Cancer Institute [R01CA203809], National Institutes of Health. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations:

- (MTF)

Monitoring the Future

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coronado VG, Basabaraju SV, McGuire LC, et al. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury—related deaths—United States, 1997–2007. Surveill Summ. 2011;60(SS05):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Traumatic brain injury in the United States. Emergency departments visits, hospitalizations and deaths, 2001–2010. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2010. www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/data/index.html. Accessed December 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faul M, Xu L, Wald MM, Coronado VG. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/blue_book.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veliz P, McCabe SE, Eckner JT, Schulenberg J. Prevalence of concussion among U.S. adolescents and correlated factors. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1180–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilie G, Boak A, Adlaf EM, Asbridge M, Cusimano MD. Prevalence and correlates of traumatic brain injuries among adolescents. JAMA. 2013;309(24): 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilie G, Boak A, Mann RE, et al. Energy drinks, alcohol, sports and traumatic brain injuries among adolescents. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9): e0135860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilie G, Mann RE, Hamilton H, et al. Substance use and related harms among adolescents with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015; 30(5):293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livingston EM, Thornton AE, Cox DN. Traumatic brain injury in adolescents: incidence and correlates. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiarty. 2017;56(10):895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjork JM, Grant SJ. Does Traumatic Brain Injury Increase Risk for Substance Abuse? J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(7):1077–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bombardier CH, Rimmele CT, Zintel H: The magnitude and correlates of alcohol and drug use before traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(12):1765–1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigan JD. Substance abuse as a mediating factor in outcome from traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(4):302–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parry-Jones BL, Vaughan FL, Miles Cox W. Traumatic brain injury and substance misuse: A systematic review of prevalence and outcomes research (1994–2004). Neuropsychol. 2006;16(5):537–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argyrioua E, Umb M, Carronb C, Cydersb MA. Age and impulsive behavior in drug addiction: A review of past research and future directions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2018;164:106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. (2008). Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 2008;32(5):723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keyes KM, Jager J, Hamilton A, O’Malley PM, Miech R, Schulenberg JE. National multi-cohort time trends in adolescent risk preference and the relation with substance use and problem behavior from 1976 to 2011. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malmberg M, Overbeek G, Monshouwer K, Lammers J, Vollebergh WA, Engels RC. Substance use risk profiles and associations with early substance use in adolescence. J Behav Med. 2010;33(6):474–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Res. 2013:35(2);193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beidler E, Covassin T, Donnellan M, Nogle S, Pontifex MB, Kontos AP. Higher risk-taking behavioursbehaviors and sensation seeking needs in collegiate student-athletes with a history of multiple sport-related concussions. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):A66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim E Agitation, aggression, and disinhibition syndromes after traumatic brain injury. Neurorehabilitation. 2002;17(4): 297–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connor KL, Dain Allred C, Cameron KL, et al. The prevalence of concussion within the military academies: findings from the concussion assessment, research, and education (care) consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):A33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2016: Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. The Monitoring the Future Project After Four Decades: Design and Procedures (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 82). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Issues of validity and population coverage in student surveys of drug use. NIDA Res Monogr 1985;57:31–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown TN, Schulenberg J, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Consistency and change in correlates of youth substance use, 1976-1997. (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 49). Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veliz P, Boyd C, McCabe SE. Competitive sport involvement and substance use among adolescents: a nationwide study. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(2):156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85–95 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarrett N, Veliz P, Sabo D. Teen Sport in America: Why Participation Matters. Meadow, NY: Women’s Sports Foundation; 2018. https://www.womenssportsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/teen-sport-in-america-full-report-web.pdf. Accessed Feburary 15, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veliz P Variation in national survey estimates and youth traumatic brain injury – Where does the truth lie? JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veliz P, Eckner JT, Zdroik J, Schulenberg J. Lifetime prevelance of self-reported concussion among adolescents involved in competitive sports: a national US study. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(2):272–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]