Abstract

Background

Lung cancer screening (LCS) requires complex processes to identify eligible patients, provide appropriate follow-up, and manage findings. It is unclear whether LCS in real-world clinical settings will realize the same benefits as the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST).

Objective

To evaluate the impact of process modifications on compliance with LCS guidelines during LCS program implementation, and to compare patient characteristics and outcomes with those in NLST.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO), a non-profit integrated healthcare system.

Patients

A total of 3375 patients who underwent a baseline lung cancer screening low-dose computed tomography (S-LDCT) scan between May 2014 and June 2017.

Measurements

Among those receiving an S-LDCT, proportion who met guidelines-based LCS eligibility criteria before and after LCS process modifications, differences in patient characteristics and outcomes between KPCO LCS patients and the NLST cohort, and factors associated with a positive screen.

Results

After modifying LCS eligibility confirmation processes, patients receiving S-LDCT who met guidelines-based LCS eligibility criteria increased from 45.6 to 92.7% (P < 0.001). Prior to changes, patients were older (68 vs. 67 years; P = 0.001), less likely to be current smokers (51.3% vs. 52.5%; P < 0.001), and less likely to have a ≥ 30-pack-year smoking history (50.0% vs. 95.3%; P < 0.001). Compared with NLST participants, KPCO LCS patients were older (67 vs. 60 years; P < 0.001), more likely to currently smoke (52.3% vs. 48.1%; P < 0.001), and more likely to have pulmonary disease. Among those with a positive baseline S-LDCT, the lung cancer detection rate was higher at KPCO (9.4% vs. 3.8%; P < 0.001) and was positively associated with prior pulmonary disease.

Conclusion

Adherence to LCS guidelines requires eligibility confirmation procedures. Among those with a positive baseline S-LDCT, comorbidity burden and lung cancer detection rates were notably higher than in NLST, suggesting that the study of long-term outcomes in patients undergoing LCS in real-world clinical settings is warranted.

KEY WORDS: lung cancer screening implementation, National Lung Screening Trial

INTRODUCTION

Since the 2011 publication of the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) findings demonstrated a 20% reduction in lung cancer deaths in the screened group, low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) has been accepted as an efficacious population-based approach for lung cancer screening (LCS).1 The trial findings, and subsequent recommendations from the US Preventative Services Task Force,2 resulted in LCS via LDCT being implemented in a variety of community and academic clinical settings.3–12 Most LCS programs base eligibility criteria on the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendations (ages 55–80 with ≥ 30 pack-years smoked and smoked in the last 15 years) and the additional Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) payment requirements.13 Thus, inaccurate or incomplete smoking history documentation in the electronic health record,3,5,8 incorrectly calculated pack-years,3,5 and ineligible patients receiving LCS-related LDCT scans8–10 present substantial challenges for implementation, uptake, and evaluation of LCS programs in real-world clinical settings. Because clinical trial data suggests that the benefits of LCS via LDCT outweigh the risks in those who meet the guidelines-based LCS eligibility criteria and that benefits are uncertain in other groups, it is important to ensure guidelines-concordant LCS practices.2 Moreover, CMS payment requirements related to shared decision-making and smoking cessation support, along with follow-up testing and handling of incidental findings identified via screening LDCT (S-LDCT), result in additional complexity for LCS workflows.3,5,6,8,9,12,14,15

The US Preventive Services Task Force “Grade B” recommendation for LCS via LDCT and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act requirements necessitated that health systems begin offering S-LDCT scans that require no copays for eligible members in 2013. In 2015, the CMS published a decision memo outlining specific LCS eligibility criteria that needed to be met.16 Thus, the primary objective of this study is to describe the implementation of LCS in a real-world clinical setting and to evaluate the impact of workflow changes that took place over the first 3 years of LCS implementation. Specifically, we examined the impact of process and staffing modifications aimed at improving adherence to US Preventive Services Task Force and CMS guidelines–based LCS by comparing the patients undergoing S-LDCTs within Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) “pre-” and “post-” referral and staffing changes. We also compared KPCO participants to published data that describe NLST participant characteristics.1,17,18 In addition, we examined variation in outcomes after a positive baseline S-LDCT between the KPCO and NLST cohorts,18 and evaluated demographic and clinical characteristics associated with positive S-LDCTs.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cohort analysis assessed the changes in demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients receiving a baseline S-LDCT between May 1, 2014, and June 30, 2017 with follow-up for outcomes and complications through June 30, 2018. Patients received their care at KPCO, a non-profit integrated healthcare delivery system. This study was reviewed and approved by the KPCO Institutional Review Board.

Lung Cancer Screening Implementation and Modifications

Implementation of LCS at KPCO began in May 2014, in a collaboration between the KPCO Population Health, Radiology, and Pulmonology departments. During a primary care visit, LCS eligibility—based on age and smoking history—was displayed in the EPIC®-based electronic health record patient landing page. The primary care provider would use shared decision-making tools provided within the electronic health record and, if the patient agreed, an S-LDCT was ordered. However, no process existed to prevent the S-LDCT order if LCS eligibility was not met.

In 2015, after the CMS coverage decision, initial analyses demonstrated that a high proportion of patients who had undergone LCS were not eligible according to the US Preventive Services Task Force and CMS guidelines. Although physicians were required to use an LCS-specific procedure code, anecdotal evidence suggested that physicians used this code for diagnostic LDCTs—intentionally or unintentionally—or to circumvent patient copays. As a result, in 2015, a formal referral process and new workflow was implemented in the electronic health record. This key change in process required confirmation of age and smoking status, as well as documentation of shared decision-making and smoking cessation counseling.

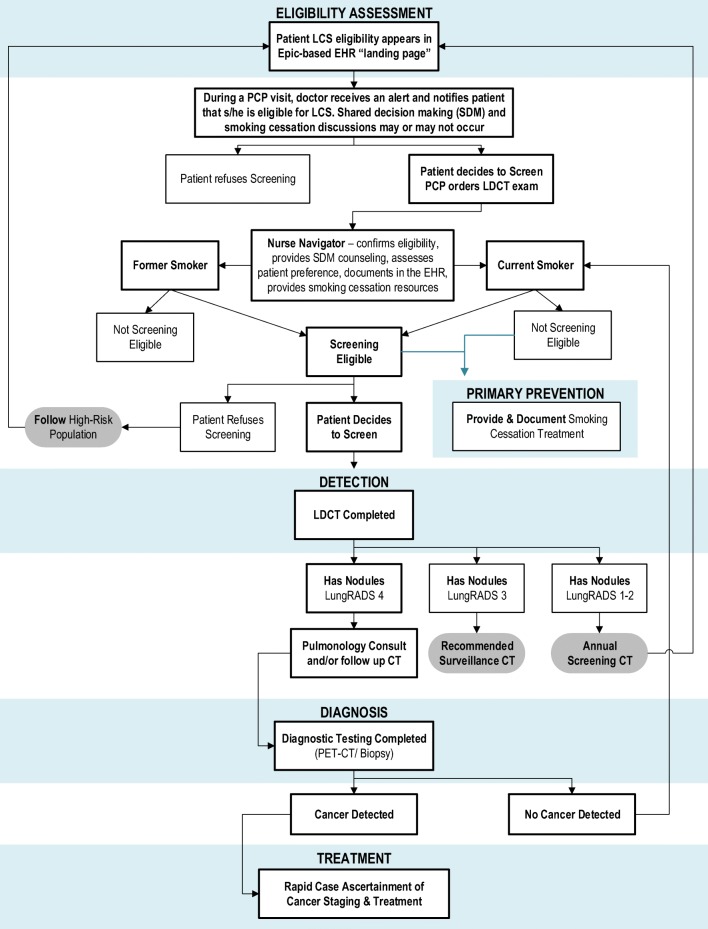

Nurse navigators within the Population Heath department were key to the new LCS workflow: nurse navigators received the LCS referral and administered a brief questionnaire to the member that assessed current smoking status, pack-years, and time since quitting smoking (among former smokers) to confirm LCS eligibility. The nurse navigators then updated smoking history in the electronic health record and if the member was confirmed to be eligible for LCS, the S-LDCT was ordered and scheduled, and the patient was entered into an electronic health record LCS reporting and tracking tool. The updated workflow process is outlined in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of KPCO LCS guidelines.

Data Sources

The primary data source for this analysis was the KPCO Virtual Data Warehouse. The Virtual Data Warehouse is the local research-ready database that contains data consistent with the standards and definitions used in the Health Care Systems Research Network and the Cancer Research Network.19,20 The Virtual Data Warehouse contains patient-level data extracted from the electronic health record, administrative, and claims databases,21–25 including tumor registry, procedure, diagnosis, census-based measures of socioeconomic status (e.g., median neighborhood education), and pharmacy data associated with all hospital and ambulatory encounters (internal and external claims). Characteristics associated with the NLST participants were derived from published trial results.1,17,18

Study Sample

KPCO members in the Denver/Boulder service area who received an LDCT between May 1, 2014, and June 30, 2017, were identified, and the first S-LDCT within that period was the baseline S-LDCT for each patient (Fig. 2). The cohort was split by patients whose baseline S-LDCT occurred prior to LCS program modifications (May 2014 through March 2015; the “pre-cohort”) and patients whose baseline S-LDCT occurred after LCS program modifications (April 2015 through June 2017; the “post-cohort”). Consistent with the follow-up period used in the evaluation of baseline S-LDCT in the NLST, patients were followed from baseline S-LDCT date to lung cancer diagnosis, their next LDCT, death, disenrollment from KPCO, or 12 months, whichever came first.18

Fig. 2.

Selection of LCS cohort.

Primary Outcomes

Among those receiving a baseline S-LDCT, primary outcomes included as follows: (1) the proportion who met guidelines-based LCS eligibility criteria (ages 55–80 years old with a ≥ 30-pack-year smoking history who have smoked in the past 15 years), and (2) the proportion of patients who had positive S-LDCT results based on a Lung-RADS assignment of 3 or 4.26 In addition, we compared KPCO patient demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes with those in the NLST. Lastly, we evaluated factors associated with a positive baseline S-LDCT.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to compare the characteristics of patients receiving S-LDCT between the pre- and post-cohorts. We calculated the proportion of patients who received an S-LDCT by age, sex, race, median neighborhood educational attainment, and the Quan adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).27 Differences in baseline characteristics of the pre-cohort patients compared with those of the post-cohort patients as well as characteristics of the overall KPCO LCS cohort compared with those enrolled in the NLST were evaluated using chi-square or Fisher exact tests. Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The association between patient characteristics and a positive S-LDCT (i.e., Lung-RADS 3 or 4) was evaluated using multivariable logistic regression. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were generated to measure the association for each of the following factors: age, gender, race, smoking status, pack-year history, years since quitting, census-based median family income, census-based education levels, CCI, pulmonary conditions, previous cancer diagnoses, and insurance status at time of S-LDCT. Customary residual and effect statistics were examined to assess model fit and evaluate for outliers.28 All analyses were performed using the SAS® Studio Software version 3.7 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 56,609 LDCT scans at KPCO between May 1, 2014, and June 30, 2017 (Fig. 2). After limiting to KPCO members with an S-LDCT in the Denver/Boulder service area, we included 3375 patients in the study cohort. A total of 653 patients received their baseline S-LDCT prior to workflow modifications (the pre-cohort), and 2722 patients received their baseline S-LDCT after workflow modifications (the post-cohort).

Patient Demographics Before and After Implementing the LCS Process Improvement

After implementing the new workflow processes, the percentage of patients who met eligibility criteria increased from 45.6 to 92.7% (P < 0.001; Table 1). Patients in the pre-cohort were older (68 years, IQR = 10 years vs. 67 years, IQR = 10 years, respectively; P < 0.001), less likely to be a current smoker (51.3% vs. 52.5%, respectively; P < 0.001), and less likely to have a ≥ 30-pack-year smoking history (50.0% vs. 95.3%, respectively; P < 0.001) than those in the post-cohort. Patients in the pre-cohort had a lower comorbidity burden than those in the post-cohort (37.8% vs. 32.4% with zero comorbid conditions, respectively; P = 0.02); specifically, there were fewer patients with asthma (8.6% vs. 26.9%; P < 0.001) and diabetes (15.5% vs. 20.6%; P = 0.003). Patients in the pre-cohort lived in neighborhoods with higher incomes (24.1% in the highest quintile vs. 19.0% in the highest quintile in the post-cohort; P = 0.02) and higher education levels (47% with bachelor’s degree or more vs. 45%; P < 0.001). There were no differences in the distribution of race or gender between the two cohorts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Undergoing a Baseline Lung Cancer Screening LDCT (S-LDCT)

| Pre (May 2014–Mar 2015) (N = 653) | Post (Apr 2015–Jun 2017) (N = 2722) | Total (N = 3375) | P value Pre versus post | NLST1, 17 (N = 26,310) | P value KPCO versus NLST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Met LCS eligibility criteria, N (%) | 298 (45.6) | 2524 (92.7) | 2822 (83.6) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Age at baseline S-LDCT, N (%) | ||||||

| < 55 | 24 (3.7) | 11 (0.4) | 35 (1.3) | < 0.001 | 2 (< 0.1) | < 0.001 |

| 55–64 | 183 (28.0) | 956 (35.1) | 1139 (33.7) | 19,304 (73.4) | ||

| 65–74 | 318 (48.7) | 1369 (50.3) | 1687 (50.0) | 7003 (26.6) | ||

| 75–79 | 81 (12.4) | 308 (11.3) | 389 (11.5) | 1 (< 0.1) | ||

| 80+ | 47 (7.2) | 78 (2.9) | 125 (3.7) | 0 | ||

| Age, median (IQR) | 68 (10) | 67 (10) | 67 (10) | < 0.001 | 60 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status at baseline S-LDCT, N (%) | ||||||

| Current | 335 (51.3) | 1430 (52.5) | 1765 (52.3) | < 0.001 | 12,642 (48.1) | < 0.001 |

| Quit/former | 291 (44.6) | 1271 (46.7) | 1562 (46.3) | 13,668 (51.9) | ||

| Never | 24 (3.7) | 16 (0.6) | 40 (1.2) | 0 | ||

| Missing | 3 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 8 (0.2) | 0 | ||

| Pack-year history, N (%) | ||||||

| < 30 pack-years | 159 (24.3) | 47 (1.7) | 206 (6.1) | < 0.001 | 6 (< 0.01) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 30 pack-years | 326 (50.0) | 2593 (95.3) | 2919 (86.5) | 26,303 (100) | ||

| Unknown | 168 (25.7) | 82 (3.0) | 250 (7.4) | 0 | ||

| Median pack-years (IQR) | 35 (14.5) | 40.5 (15) | 40 (15) | < 0.001 | 48 (27) | < 0.001 |

| Years since quitting, N (%) | ||||||

| Current smoker | 335 (51.3) | 1430 (52.5) | 1765 (52.3) | < 0.001 | 12,642 (48.1) | < 0.001 |

| < 15 years | 194 (29.7) | 1184 (43.5) | 1378 (40.8) | 13,612 (51.7) | ||

| ≥ 15 years | 47 (7.2) | 35 (1.3) | 82 (2.4) | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 77 (11.8) | 73 (2.7) | 150 (4.4) | 55 (0.2) | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, N (%) | ||||||

| 0 (good health) | 247 (37.8) | 883 (32.4) | 1130 (33.5) | 0.02 | NA | NA |

| 1–3 (average health) | 336 (51.5) | 1484 (54.5) | 1820 (53.9) | NA | NA | |

| 4 or more (poor health) | 70 (10.7) | 355 (13.0) | 425 (12.6) | NA | NA | |

| Comorbid conditions in year prior to baseline S-LDCT, N (%) | ||||||

| Asbestosis | 3 (0.5) | 9 (0.3) | 12 (0.4) | 0.71 | 276 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| Asthma | 56 (8.6) | 732 (26.9) | 788 (23.3) | < 0.001 | 1666 (6.3) | < 0.001 |

| Bronchiectasis | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 0.58 | 854 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 55 (8.4) | 670 (24.6) | 725 (21.5) | < 0.001 | 2592 (9.9) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 201 (30.8) | 897 (33.0) | 1098 (32.5) | 0.29 | 1347 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| Emphysema | 48 (7.4) | 211 (7.8) | 259 (7.7) | 0.73 | 2056 (7.8) | 0.78 |

| Chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD | 201 (30.8) | 897 (33.0) | 1098 (32.5) | 0.29 | 4674 (17.8) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 101 (15.5) | 560 (20.6) | 661 (19.6) | 0.003 | 2550 (9.7) | < 0.001 |

| Fibrosis | 2 (0.3) | 13 (0.5) | 15 (0.4) | 0.75 | 70 (0.3) | 0.07 |

| Heart disease* | 81 (12.4) | 414 (15.2) | 495 (14.7) | 0.07 | 3402 (12.9) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 283 (43.3) | 1240 (45.6) | 1523 (45.1) | 0.31 | 9295 (35.3) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 36 (5.5) | 136 (5.0) | 172 (5.1) | 0.59 | 5856 (22.3) | < 0.001 |

| Sarcoidosis | 0 | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | > 0.99 | 48 (0.2) | NA |

| Silicosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 30 (0.1) | NA |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 281 (1.0) | NA |

| Stroke | 4 (0.6) | 14 (0.5) | 18 (0.5) | 0.77 | 753 (2.9) | < 0.001 |

| Any of the above diseases | 432 (66.2) | 1927 (70.8) | 2359 (69.9) | 0.02 | 17,567 (66.8) | < 0.001 |

| Median family income (census tract quintile), N (%) | ||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 110 (16.8) | 564 (20.7) | 674 (20.0) | 0.02 | NA | NA |

| 2 | 132 (20.2) | 546 (20.1) | 678 (20.0) | NA | NA | |

| 3 | 123 (18.8) | 552 (20.3) | 675 (20.0) | NA | NA | |

| 4 | 130 (19.9) | 543 (19.9) | 673 (20.0) | NA | NA | |

| 5 (highest) | 158 (24.1) | 517 (19.0) | 675 (20.0) | NA | NA | |

| Education (census tract), % with college education+ | 47% | 45% | 45% | < 0.001 | 31% | ND |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||||

| Male | 353 (54.1) | 1530 (56.2) | 1883 (55.8) | 0.32 | 15,537 (59.1) | < 0.001 |

| Race, N (%) | ||||||

| Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 18 (2.8) | 51 (1.9) | 69 (2.0) | 0.33 | 546 (2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Black | 26 (4.0) | 118 (4.3) | 144 (4.3) | 1167 (4.4) | ||

| Other | 38 (5.8) | 122 (4.5) | 160 (4.7) | 499 (1.9) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 47 (7.2) | 185 (6.8) | 232 (6.9) | 96 (0.4) | ||

| White | 524 (80.2) | 2246 (82.5) | 2770 (82.1) | 24,002 (91.2) | ||

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 64 (9.8) | 272 (10.0) | 336 (10.0) | 0.82 | 464 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Lung-RADS, N (%) | ||||||

| No Lung-RADS assignment | 190 (29.1) | 84 (3.1) | 274 (8.1) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| 1 | 123 (18.8) | 276 (10.1)† | 399 (11.8) | NA | NA | |

| 2 | 232 (35.5) | 1803 (66.2)‡ | 2035 (60.3) | NA | NA | |

| 3 | 49 (7.5) | 388 (14.3)§ | 437 (12.9) | NA | NA | |

| 4A | 37 (5.7) | 107 (3.9) | 144 (4.3) | NA | NA | |

| 4B | 22 (3.4) | 62 (2.3) | 84 (2.5) | NA | NA | |

| 4X | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | NA | NA | |

| Positive S-LDCT result (Lung-RADS 3 or 4)║, N (%) | 108 (16.5) | 559 (20.5) | 667 (19.8) | 0.02 | 7049 (26.8) | < 0.001 |

| Confirmed lung cancer diagnosis, N (%) | 18 (2.8) | 59 (2.2) | 77 (2.3) | 0.37 | 292 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Previous malignancies, N (%) | ||||||

| Previous solid tumor (excluding lung) | 44 (6.7) | 223 (8.2) | 267 (7.9) | 0.22 | 1063 (4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Previous lung cancer | 9 (1.4) | 6 (0.2) | 15 (0.4) | < 0.001 | 10 (< 0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Insurance Status at time of screening, N (%) | ||||||

| HMO | 436 (66.8) | 1756 (64.5) | 2192 (64.9) | 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Deductible | 151 (23.1) | 780 (28.7) | 931 (27.5) | NA | NA | |

| Other | 66 (10.1) | 186 (6.8) | 252 (7.5) | NA | NA | |

*Heart disease measured as at least one of any of the following conditions: congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or MI †Post-number contains 2 people with Lung-RADS = 1S ‡Post-number contains 2 people with Lung-RADS = 2C and 31 people with RADS = 2S §Post-number contains 4 people with Lung-RADS = 3S ║Size for a positive S-LDCT lung nodule during the KPCO time period was 6 mm. Size for positive S-LDCT lung nodule for NLST was 4 mm

Patient Demographics Compared with NLST

Compared with NLST, the KPCO cohort was older (67 vs 60 years; P < 0.001), more likely to be current smokers (52.3% vs. 48.1%; P < 0.001), and more diverse (82.1% white vs. 91.2% white; P < 0.001; 10.0% Hispanic vs. 1.8% Hispanic; P < 0.001) than NLST participants. KPCO patients had more comorbidity including asthma, chronic bronchitis, COPD, diabetes, and hypertension (all P < 0.001; Table 1). Overall, there were 292 lung cancer cases detected among NLST participants after baseline screen (1.1%) while KPCO detected 77 (2.3%; P < 0.001).

Comparison of Outcomes Between the Pre- and Post-cohorts Among KPCO Patients with Positive Baseline Screens

S-LDCTs with a Lung-RADS 3 or 4 were considered positive, and patients in the KPCO pre-cohort had fewer positive S-LDCTs than patients in the post-cohort (16.5% vs. 20.5%; P = 0.02). Among patients with a positive S-LDCT (N = 667), there were 63 lung cancers detected (9.3% in the pre-cohort and 9.5% in the post-cohort; P = 0.94; Table 2). Relative to the post-cohort, a larger proportion of patients in the pre-cohort either did not have a Lung-RADS assignment or had the highest risk Lung-RADS category, Lung-RADS 4 (P < 0.001). The distribution of recommended follow-up time was significantly different between the pre- and post-cohorts (P < 0.001). For patients in the pre-cohort, the most common recommended interval follow-up for nodule management was 3 months (41.7%) versus 6 months in the post-cohort. There was no significant difference in the distribution of advanced (stage IIIB–IV) lung cancers between the pre- and post-cohorts (40.0% vs. 22.6%; P = 0.26).

Table 2.

Distribution of Outcomes Among Patients with a Positive S-LDCT

| Pre (May 2014–Mar 2015) (N = 108) | Post (Apr 2015–Jun 2017) (N = 559) | Total (N = 667)* | P value Pre versus post | NLST18 (N = 7049)* | P value KPCO versus NLST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung cancer diagnosis, N (%) | ||||||

| Total number (%) | 10 (9.3) | 53 (9.5) | 63 (9.4) | 0.94 | 270 (3.8) | < 0.001 |

| Stage I–IIIA | 6 (60.0) | 41 (77.4) | 47 (74.6) | 0.26 | 204 (75.6) | > 0.99 |

| Stage IIIB–IV | 4 (40.0) | 12 (22.6) | 16 (25.4) | 62 (23.0) | ||

| Unknown stage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.5) | ||

| Histologic type, N (%) | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 2 (20.0) | 21 (39.6) | 23 (36.5) | 0.50 | 118 (43.7) | < 0.001 |

| Bronchioloalveolar | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.2) | 38 (14.1) | ||

| Carcinoid | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.2) | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Non-small cell | 4 (40.0) | 9 (17.0) | 13 (20.6) | 34 (12.6) | ||

| Small cell | 0 | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.2) | 15 (5.6) | ||

| Squamous carcinoma | 4 (40.0) | 17 (32) | 21 (33) | 47 (17.4) | ||

| Large cell | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (5.2) | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | ||

| Follow-up post-baseline S-LDCT, N (%)† | ||||||

| Other chest CTs | 63 (58.3) | 361 (64.6) | 424 (63.6) | 0.22 | 5153 (73.1) | < 0.001 |

| PET | 21 (19.4) | 107 (19.1) | 128 (19.1) | 0.94 | 728 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

| Chest X-ray | 21 (19.4) | 133 (23.8) | 154 (23.1) | 0.33 | 1284 (18.2) | 0.002 |

| Any chest CT, PET, or X-ray | 74 (68.5) | 422 (75.5) | 496 (74.5) | 0.13 | 5717 (81.1) | < 0.001 |

| Bronchoscopy | 2 (1.9) | 9 (1.6) | 11 (1.6) | 0.70 | 306 (4.3) | < 0.001 |

| Percutaneous biopsy | 2 (1.9) | 17 (3.0) | 19 (2.8) | 0.75 | 155 (2.2) | 0.28 |

| Pleural drainage | 0 | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.7) | > 0.99 | NA | NA |

| Any bronchoscopy, percutaneous biopsy, pleural drainage | 6 (5.6) | 31 (5.5) | 37 (5.5) | > 0.99 | NA | NA |

| Thoracoscopy | 3 (2.8) | 6 (1.1) | 9 (1.3) | 0.17 | 82 (1.1) | 0.67 |

| Thoracotomy | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | > 0.99 | 197 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Mediastinoscopy/mediastinotomy | 0 | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | > 0.99 | 60 (0.9) | 0.27 |

| Utilization within 30 days after baseline S-LDCT, N (%) | ||||||

| ER visit | 2 (1.9) | 21 (3.8) | 23 (3.4) | 0.56 | NA | NA |

| Inpatient admission | 2 (1.9) | 7 (1.3) | 9 (1.3) | 0.64 | NA | NA |

| Death during study follow-up time‡, N (%) | 5 (4.6) | 18 (3.2) | 23 (3.4) | 0.40 | NA | NA |

| Clinical findings within 12 months post S-LDCT, N (%) | ||||||

| Respiratory failure | 6 (5.6) | 8 (1.4) | 14 (2.1) | 0.02 | NA | NA |

| Mediastinal adenopathy | 4 (3.7) | 10 (1.8) | 14 (2.1) | 0.26 | 277 (3.9) | 0.02 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 (2.8) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | 0.03 | 456 (6.5) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic bronchitis (newly diagnosed) | 14 (13.0) | 66 (11.8) | 80 (12.0) | 0.73 | NA | NA |

| Atelectasis | 7 (6.5) | 32 (5.7) | 39 (5.8) | 0.76 | 72 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| Emphysema | 3 (2.8) | 82 (14.7) | 85 (12.7) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Any 1 or more of the clinical findings above | 27 (25.0) | 179 (32.0) | 206 (30.9) | 0.15 | NA | NA |

| Other clinical findings§ | 6 (5.6) | 19 (3.4) | 25 (3.7) | 0.27 | NA | NA |

| Recommended follow-up, N (%) | ||||||

| 3 months | 45 (41.7) | 101 (18.1) | 146 (21.9) | < 0.001 | NA | NA |

| 6 months | 29 (26.9) | 323 (57.8) | 352 (52.8) | NA | NA | |

| 12 months | 10 (9.3) | 11 (2.0) | 21 (3.1) | NA | NA | |

| Completed program | 7 (6.5) | 1 (0.2) | 8 (1.2) | NA | NA | |

| Pulmonary referral | 17 (15.7) | 123 (22.0) | 140 (21.0) | NA | NA | |

*Nodules with a Lung-RADS classification of 3 or 4 were considered to be positive at KPCO. All non-calcified nodules with long-axis diameters of 4 mm or greater in the axial plane were considered to be positive in NLST †Follow-up from baseline S-LDCT to end of study (first of lung cancer diagnosis, their next LDCT screen, death, disenrollment from KPCO, or 12 months) ‡Death assessed from study entry through to end of study (first of lung cancer diagnosis, their next S-LDCT, death, disenrollment from KPCO, or 12 months) §Other clinical findings include as follows: anaphylaxis, brachial plexopathy, bronchiectasis, cardiac arrest, empyema, fibrosis, hemothorax, contrast-induced nephropathy, pneumothorax, sarcoidosis, and stroke/CVA

Positive Screen Outcome Comparison Between KPCO and NLST

Among those with a positive S-LDCT, there were 270 (3.8%) NLST participants compared with 63 at KPCO (9.4%; P < 0.001) diagnosed with lung cancer. There was no significant difference in the distribution of late-stage cancers (i.e., stage IIIB/IV) between KPCO and NLST participants (25.4% KPCO vs. 23.0% NLST, respectively; P > 0.999). KPCO had significantly fewer follow-up imaging procedures (chest CTs, PETs, or chest x-rays) than NLST (74.5% vs. 81.1%; P < 0.001), fewer bronchoscopies (1.6% vs. 4.3%; P < 0.001), and fewer thoracotomies (0.1% vs. 2.7%; P < 0.001). KPCO had less mediastinal adenopathy (2.1% vs. 3.9%, respectively; P = 0.02) and less pleural effusion (0.7% vs. 6.5%, respectively; P < 0.001) diagnosed than NLST participants.

Factors Associated with a Positive S-LDCT Result

In univariate models, increasing age, and COPD or pneumonia diagnosed in the year prior to baseline S-LDCT were significantly associated with increased odds of having a positive S-LDCT result, while non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity was associated with reduced odds of having a positive S-LDCT result (Table 3). In the fully adjusted logistic regression model, age at the time of S-LDCT (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.04 per 1-year increase, 95% CI = 1.03 to 1.06), a diagnosis of COPD in the prior year (AOR = 1.35, 95% CI = 1.07 to 1.71), and a diagnosis of pneumonia in the prior year (AOR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.09 to 2.30) remained significant.

Table 3.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Associated with a Positive S-LDCT

| Patient characteristics | N (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at S-LDCT, mean (SD) | 67 (6) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1731 (56) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Female | 1370 (44) | 0.99 (0.83–1.17) | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2446 (79) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 127 (4) | 0.58 (0.35–0.97) | 0.61 (0.36–1.02) |

| Hispanic | 312 (10) | 0.84 (0.62–1.13) | 0.93 (0.68–1.26) |

| Other/unknown† | 216 (7) | 1.01 (0.72–1.41) | 1.04 (0.74–1.46) |

| Quit years | |||

| Current smoker | 1631 (53) | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 15 years | 1313 (42) | 0.96 (0.81–1.15) | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) |

| ≥ 15 years | 55 (2) | 0.80 (0.40–1.60) | 0.95 (0.39–2.31) |

| Unknown | 102 (3) | 1.04 (0.65–1.68) | 1.15 (0.69–1.92) |

| Pack-year history | |||

| ≥ 30 | 2793 (90) | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 30 | 147 (5) | 1.13 (0.77–1.67) | 1.02 (0.67–1.54) |

| Unknown | 161 (5) | 0.73 (0.48–1.11) | 0.64 (0.36–1.13) |

| Median census education (% with college or greater) [IQR] | 45 [32, 59] | 0.72 (0.46–1.14) | 0.71 (0.45–1.14) |

| Year of S-LDCT | |||

| 2014 | 281 (9) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2015 | 973 (31) | 1.06 (0.78–1.46) | 1.01 (0.73–1.41) |

| 2016 | 1194 (39) | 0.78 (0.57–1.07) | 0.78 (0.55–1.11) |

| 2017 | 653 (21) | 0.89 (0.64–1.25) | 0.95 (0.66–1.38) |

| Specific comorbid conditions | |||

| Asthma | 750 (24) | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) | 0.98 (0.76–1.28) |

| COPD | 1010 (33) | 1.53 (1.28–1.83) | 1.35 (1.07–1.71) |

| Diabetes | 617 (20) | 0.96 (0.77–1.19) | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) |

| Heart disease | 446 (14) | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) |

| Hypertension | 1409 (45) | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) |

| Pneumonia | 146 (5) | 1.67 (1.16–2.40) | 1.58 (1.09–2.30) |

| Previous non-lung solid tumor | 243 (8) | 1.05 (0.76–1.44) | 0.94 (0.68–1.30) |

| Insurance status | |||

| HMO | 2007 (65) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Deductible | 867 (28) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) | 0.94 (0.75–1.18) |

| Other‡ | 227 (7) | 0.81 (0.58–1.14) | 1.09 (0.75–1.58) |

*Model mutually adjusted for all variables listed in this table

†“Other” races include Asian/Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, other, and unknown

‡“Other” insurance statuses include Medicaid, self-funded, triple option, and two-tier products

DISCUSSION

This is, to our knowledge, the first description of a comprehensive LCS program in a real-world clinical setting that highlights iterative developments in the screening process and their impact on LCS patient characteristics and outcomes relative to the NLST. Prior to implementing measures to ensure eligibility, only 46% of the patients receiving an S-LDCT reliably met eligibility criteria. After process improvement, the percent of patients receiving S-LDCT who met eligibility criteria jumped to 93%. This finding is consistent with two recently published studies using data from the National Health Interview survey that found slow uptake and underuse of screening and the number of adults inappropriately screened for lung cancer in excess of the number screened in accordance with the US Preventive Services Task Force LCS guidelines.29,30

Clinical Characteristics and Health Outcomes

Relative to NLST participants, and consistent with another recent study associated with screening in a non-trial setting,31 patients at KPCO who received a baseline S-LDCT (both pre- and post-implementation of modifications) were older (P < 0.001), were more likely to be current smokers (P < 0.001), and had a higher comorbidity burden (P < 0.001). One possible explanation for the demographic differences between the pre- and post-cohorts is that prior to workflow modifications, healthier patients may have been more engaged in healthcare and may have sought LCS despite not meeting eligibility criteria. This hypothesis is supported by an analysis of an LCS program in a large healthcare system in California. This analysis found that those with severe or moderate comorbidity (severe vs. no major comorbidity: OR = 0.2, 95% CI = 0.1–0.3; moderate vs. no major comorbidity: OR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.4–0.7) were less likely to receive S-LDCT orders, and that a visit to a primary care provider (vs. other providers: OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.7–3.4) was associated with increased likelihood of S-LDCT orders.32 Alternatively, primary care providers may have mistakenly used the S-LDCT-specific order code for diagnosing other conditions not associated with LCS (e.g., chest pain) and/or limiting the burden of imaging copays for the patient.

KPCO diagnosed 77 lung cancers (2.3% of all screens). This is consistent with NLST findings and rates reported by Milch et al. and Wilson et al. (both 2%) but is slightly higher than the 1–2% lung cancer yield reported by other studies.3,9,11,12,33 A higher proportion of lung cancers identified via screening at KPCO were diagnosed at potentially curable stages I–IIIA than reported by Lanni et al. in a different LCS setting (74.6% vs. 39%).11 There is a clinically significant trend toward lower rates of advanced cancers in the post-cohort, suggesting that more stringent adherence to eligibility criteria may lead to important improvements in screening outcomes.

Prevalence of follow-up imaging and procedures at KPCO was similar to other settings. Wagnetz et al. reported a biopsy rate of 3% in their lung cancer screening study; the KPCO rate was 2.8%.34 Wilson et al. reported a thoracoscopy/thoracotomy rate of 2%, while the rate at KPCO was 1.3% and 0.1%, respectively.33

The LCS Process

Adhering to eligibility guidelines is a common barrier in LCS; McKee et al. reported that 18% of patients screened did not meet eligibility criteria, and Milch et al. reported that 38% did not meet criteria.9,12 The most common reason for ineligibility was missing, incomplete, or outdated smoking history data (i.e., smoking status, quit dates, and pack-year history).32 However, consistent with the findings of Triplette et al., additional provider and health system resources are needed to capture complete smoking history and eligibility for every patient,35 as was the case for KPCO. If the estimated societal benefits associated with the NLST36 are going to be realized within real-world clinical settings, it may be important for providers and health systems to invest in these types of LCS process enhancements.

Other barriers to LCS include avoidable cost and risk of complications. LCS follow-up procedures to investigate positive S-LDCTs, such as biopsies, may unnecessarily place patients at risk for complications. Moreover, LCS exams in patients who do not meet LCS eligibility criteria result in increased costs to patients and health systems, and there is no evidence for benefits to these patients.2 In patients with significant comorbidities or those unable to undergo surgery, competing causes of death may diminish the benefit of LCS.37,38 Thus, the harms and costs of providing S-LDCT to patients who do not meet eligibility criteria may be substantial.

Limitations

This study presents the impacts of LCS process improvement initiatives on patient outcomes in a large real-world clinical setting; however, it is not without its limitations. First, our findings may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems that do not operate under an integrated care delivery model with mature electronic health records and IT infrastructures. Second, given that most patient characteristics, behaviors, and outcomes in the NLST were based on self-report rather than clinician assigned diagnostic codes captured in the electronic health record, direct comparison to all of the baseline NLST findings may be imperfect. In addition, positive S-LDCTs in our study were based on a Lung-RADS 1.0 assignment by a radiologist of 3 or 4.39 During the NLST trial, a finding of a new pulmonary nodule with a transverse diameter of > 4 mm was considered a positive S-LDCT. Pinsky and colleagues suggest that the adoption of the Lung-RADS classification system may improve the results of LCS programs and noted the need for studies like ours to confirm findings in clinical practice.40 Nevertheless, lessons learned through LCS process improvement initiatives at KPCO may inform the implementation and evaluation of processes to optimize LCS in other clinical practices and health systems.

CONCLUSION

The results of the NLST and subsequent US Preventive Services Task Force Grade B recommendations for LCS in high-risk adults provided a new avenue to reduce lung cancer mortality. In this LCS cohort, detection rates for early-stage lung cancer after baseline screen were higher than those of NLST, but long-term outcomes from this and other studies are required to determine the effectiveness of LCS programs in real-world clinical settings. To successfully implement guidelines-based LCS, it is important for health systems to evaluate the quality and effectiveness of their LCS processes and to invest in LCS process improvements to maximize benefits and reduce harms associated with LCS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Jeff Holzman.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UM1CA221939 and U24CA171524.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer VA. Force USPST. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):330–8. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, Larson M, Chan SH, King HA, et al. Implementation of Lung Cancer Screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):399–406. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caverly TJ, Fagerlin A, Wiener RS, Slatore CG, Tanner NT, Yun S, et al. Comparison of Observed Harms and Expected Mortality Benefit for Persons in the Veterans Health Affairs Lung Cancer Screening Demonstration Project. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):426–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Begnaud A, Hall T, Allen T. Lung Cancer Screening With Low-Dose CT: Implementation Amid Changing Public Policy at One Health Care System. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:e468–75. doi: 10.14694/edbk_159195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gesthalter YB, Koppelman E, Bolton R, Slatore CG, Yoon SH, Cain HC, et al. Evaluations of Implementation at Early-Adopting Lung Cancer Screening Programs: Lessons Learned. Chest. 2017;152(1):70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquinelli MM, Kovitz KL, Koshy M, Menchaca MG, Liu L, Winn R, et al. Outcomes From a Minority-Based Lung Cancer Screening Program vs the National Lung Screening Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Gould MK, Sakoda LC, Ritzwoller DP, Simoff MJ, Neslund-Dudas CM, Kushi LH, et al. Monitoring Lung Cancer Screening Use and Outcomes at Four Cancer Research Network Sites. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(12):1827–35. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-237OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.McKee BJ, McKee AB, Flacke S, Lamb CR, Hesketh PJ, Wald C. Initial experience with a free, high-volume, low-dose CT lung cancer screening program. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10(8):586–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Goulart BH, Ramsey SD. Moving beyond the national lung screening trial: discussing strategies for implementation of lung cancer screening programs. Oncologist. 2013;18(8):941–6. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lanni TB, Jr, Stevens C, Farah M, Boyer A, Davis J, Welsh R, et al. Early Results From the Implementation of a Lung Cancer Screening Program: The Beaumont Health System Experience. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41(3):218–22. doi: 10.1097/coc.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milch H, Kaminetzky M, Pak P, Godelman A, Shmukler A, Koenigsberg TC, et al. Computed tomography screening for lung cancer: preliminary results in a diverse urban population. J Thorac Imaging. 2015;30(2):157–63. doi: 10.1097/rti.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicare Coverage of Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT): Department of Health and Human Services - Ceters for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2015.

- 14.Brenner AT, Malo TL, Margolis M, Elston Lafata J, James S, Vu MB, et al. Evaluating Shared Decision Making for Lung Cancer Screening. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Copeland A, Criswell A, Ciupek A, King JC. Effectiveness of Lung Cancer Screening Implementation in the Community Setting in the United States. J Oncol Pract. 2019 Jul; 15(7):e607-e615. doi: 10.1200/jop.18.00788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N) Washington, DC2015. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274 Accessed October 14, 2019..

- 17.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Clapp JD, Clingan KL, Gareen IF, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the randomized national lung screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(23):1771–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Church TR, Black WC, Aberle DR, Berg CD, Clingan KL, Duan F, et al. Results of initial low-dose computed tomographic screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):1980–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Care Systems Research Network (HCSRN). VDW Data Model 2017. Available from: http://www.hcsrn.org. Accessed 14 Oct 2019.

- 20.National Cancer Institute Cancer Research Network. Welcome to the Cancer Research Network 2018. Available from: https://www.crn.cancer.gov/. Accessed 14 Oct 2019

- 21.Ritzwoller DP, Carroll N, Delate T, O'Keeffe-Rossetti M, Fishman PA, Loggers ET, et al. Validation of electronic data on chemotherapy and hormone therapy use in HMOs. Med Care. 2013;51(10):e67–73. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824def85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner EH, Greene SM, Hart G, Field TS, Fletcher S, Geiger AM, et al. Building a research consortium of large health systems: the Cancer Research Network. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;35:3–11. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornbrook MC, Hart G, Ellis JL, Bachman DJ, Ansell G, Greene SM, et al. Building a virtual cancer research organization. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005(35):12–25. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi033. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ross TR, Ng D, Brown JS, Pardee R, Hornbrook MC, Hart G, et al. The HMO Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse: A Public Data Model to Support Collaboration. EGEMS (Washington, DC) 2014;2(1):1049. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute. The HMO Cancer Research Network: Capacity, collaboration, and investigation,. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2010.

- 26.American College of Radiology. Lung-RADS Version 1.0 Assessment Categories 2014. Available from: https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Lung-RADS/LungRADS_AssessmentCategories.pdf?la=en. Accessed 14 Oct 2019.

- 27.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005:1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Allison PD, Chatterjee S, Hadi AS. Logistic Regression Using the SAS System: Theory and Application + Regressi: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

- 29.Richards TB, Doria-Rose VP, Soman A, Klabunde CN, Caraballo RS, Gray SC, et al. Lung Cancer Screening Inconsistent With U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huo J, Shen C, Volk RJ, Shih YT. Use of CT and Chest Radiography for Lung Cancer Screening Before and After Publication of Screening Guidelines: Intended and Unintended Uptake. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):439–41. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iaccarino JM, Steiling KA, Wiener RS. Lung Cancer Screening in a Safety-Net Hospital: Implications of Screening a Real-World Population versus the National Lung Screening Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(12):1493–5. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201806-389RL. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Li J, Chung S, Wei EK, Luft HS. New recommendation and coverage of low-dose computed tomography for lung cancer screening: uptake has increased but is still low. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):525. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3338-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Fuhrman CR, Fisher SN, Balogh P, Landreneau RJ, et al. The Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study (PLuSS): outcomes within 3 years of a first computed tomography scan. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(9):956–61. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-336OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagnetz U, Menezes RJ, Boerner S, Paul NS, Wagnetz D, Keshavjee S, et al. CT screening for lung cancer: implication of lung biopsy recommendations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):351–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.11.6726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Triplette M, Kross EK, Mann BA, Elmore JG, Slatore CG, Shahrir S, et al. An Assessment of Primary Care and Pulmonary Provider Perspectives on Lung Cancer Screening. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(1):69–75. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201705-392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Black WC, Gareen IF, Soneji SS, Sicks JD, Keeler EB, Aberle DR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CT screening in the National Lung Screening Trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1793–802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanner NT, Dai L, Bade BC, Gebregziabher M, Silvestri GA. Assessing the Generalizability of the National Lung Screening Trial: Comparison of Patients with Stage 1 Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(5):602–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0914OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howard DH, Richards TB, Bach PB, Kegler MC, Berg CJ. Comorbidities, smoking status, and life expectancy among individuals eligible for lung cancer screening. Cancer. 2015;121(24):4341–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American College of Radiology (ACR). Lung CT Screening Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADSTM) 2014. Available from: https://www.acr.org/Quality-Safety/Resources/LungRADS. Accessed 14 Oct 2019.

- 40.Pinsky PF, Gierada DS, Black W, Munden R, Nath H, Aberle D, et al. Performance of Lung-RADS in the National Lung Screening Trial: a retrospective assessment. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(7):485–91. doi: 10.7326/M14-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]