Abstract

Background

The prevalence and risk factors for non-adherence to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) in clinical practice settings are under-studied.

Objectives

(1) To quantify DAA non-adherence in the total cohort and among subgroups with and without mental health conditions, alcohol use, and substance use, and (2) to investigate patient- and treatment-level risk factor non-adherence.

Design

Prospective, observational cohort study.

Participants

A total of 1562 patients receiving DAAs between January 2016 and October 2017 at 11 US medical centers including academic and community practices.

Main Measures

Self-reported medication non-adherence, defined as any missed doses in the past 7 days, surveyed early (T2: at 4 ± 2 weeks) and late in treatment (T3: 2–3 weeks prior to end of treatment). Non-adherence to post-treatment follow-up visits was defined as absence of lab results after DAA therapy completion.

Key Results

Of 1447 patients, 162 (11%) reported non-adherence at T2 or T3. Medical records indicated 262 (17%) of the 1562 participants had not returned for post-treatment visits. At baseline, 37% of patients reported mental health conditions, 15% reported alcohol use, and 23% reported using substances in the previous year. Baseline characteristics associated with DAA non-adherence included alcohol use (OR 1.96), younger age (< 35 years vs. > 55 years: OR 3.40), non-white race (OR > 2.26), and DAA treatment cohort, but not substance use or mental health condition. Non-adherence to follow-up exhibited association with younger age and a higher baseline overall symptom burden. Among 1287 patients with evaluable sustained virologic response (SVR) data, 53 patients (4%) did not achieve SVR. The bivariate correlation between adherence and SVR was negligible (r = 0.01).

Conclusions

DAA non-adherence was low and SVR rates were high. Mental health conditions, substance use, and alcohol use should not disqualify patients from DAA therapy. Patients with alcohol use disorder before DAA therapy initiation may benefit from targeted on-treatment support.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05394-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: adherence, liver disease, alcohol use, substance use

INTRODUCTION

Medication non-adherence to hepatitis C (HCV) therapy was investigated during pegylated interferon regimens and associated with side effects and lower sustained virologic response (SVR).1 In the era of all-oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), regimens have been simplified and side effects are less severe, thereby making universal access to HCV treatment and viral elimination a realistic goal.2,3 Nonetheless, third-party payers vary with regard to approving DAA therapy for disenfranchised populations4, 5 and most state Medicaid programs continue to have alcohol and/or illicit substance abstinence requirements prior to HCV therapy approval.6

The literature on DAA adherence among people who use substances mostly comes from DAA registration trials7–9; however, even in the largest pooled analysis, patients with significant drug abuse (except cannabinoids) in the prior 12 months were excluded.8 Real-world adherence data are currently emerging among DAA-treated patients engaged in opioid substitution treatment (OST) and have shown acceptable SVRs.10–12 Despite these data, considerable gaps exist regarding the prevalence of DAA non-adherence in patients treated in real-world settings as well as the impact of mental health and substance use on adherence.11 Filling these gaps is particularly important as providers and payers may have concerns about psychosocial risk factors for non-adherence and ability to achieve SVR.13

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Project (PROP-UP) is a large prospective, multi-center study of patient-reported outcomes in a real-world HCV-infected US cohort treated with DAAs. The specific aims of the current analysis were to (1) quantify the prevalence of DAA non-adherence in the total cohort and in the subgroups with and without mental health conditions, alcohol use, and substance use at baseline; (2) understand the most common patient-reported reasons for non-adherence; (3) investigate the associations between patient- and treatment-level factors with medication non-adherence; and (4) explore the relationship between patient factors and non-adherence to clinical follow-up.

METHODS

Study Design

A total of 1601 patients were enrolled across 11 subspecialty gastroenterology/hepatology practices, 9 academic and 2 community-based. Full protocol details have previously been described.14 From January 2016 to October 2017, patients prescribed any of five DAA regimens with and without ribavirin (RBV) were eligible. Data were collected directly from participants before treatment at baseline (T1), around treatment week 4 ± 2 weeks (T2), late in treatment (2–3 weeks prior to end of treatment, T3), and 12 weeks post-treatment (T4). At each time point, participants responded to several patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and medication adherence surveys at T2 and T3. Sites obtained local Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and all participants provided informed consent.

Participants

Subgroups with Mental Health Conditions, Alcohol Use, and Substance Use

Participants responded to questions related to psychiatric history and substance and alcohol use. Participants were classified as having mental health conditions if they reported taking medications for psychiatric conditions at enrollment or had ever been psychiatrically hospitalized. Substance and alcohol use questions were adapted from the validated Substance Abuse and Mental Illness Symptoms Screener (SAMISS) and included frequency and amount of alcohol consumption and use of non-prescription street drugs and misuse of prescription medication.15, 16 Current alcohol use was defined as ≥ 5 on the SAMISS.17, 18 Substance use was classified as any self-reported use of prescription drugs to get high or use of non-prescription street drugs in the last year.

Study Outcomes

Voils’ Medication Adherence Survey

The Voils’ Medication Adherence Survey (VMAS) is an adherence questionnaire shown to be valid and reliable for HCV. It includes 3 self-reported items (“I missed my medicine”; “I skipped a dose of my medicine”; “I did not take a dose of my medicine”) that measure the extent of adherence in the past 7 days using a 5-point Likert scale (from “none of the time” to “every time”).19, 20 Patients were categorized as adherent if answering “none of the time” to all 3 items; otherwise, they were categorized as non-adherent. The primary outcome was combined non-adherence at T2 and/or T3. The VMAS also assessed reasons for non-adherence.

Non-adherence to Clinical Follow-up

This secondary non-adherence measure was defined as absence of lab results, including HCV RNA, ≥ 10 weeks after DAA therapy completion, and after multiple attempts by clinicians to schedule follow-up visits.

Sustained Virologic Response

Sustained virologic response (SVR) status was ascertained from patients’ electronic health records (EHR) and was defined as an undetectable HCV RNA at ≥ 10 weeks after treatment completion.

Covariates

Patient Characteristics and Clinical Data

Self-reported demographics, education, employment, and income were obtained at baseline. Low socioeconomic status (SES) was defined as having ≤ high school education and self-reported annual income ≤ $40,000. Clinical data were extracted from EHRs at sites. Cirrhosis was ascertained using imaging, laboratory data, and expert clinician adjudication.

Overall Symptom Burden

A comprehensive list of 32 symptoms common to many health conditions was assessed using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) at baseline.21, 22 A total MSAS (TMSAS) score was calculated from the average of all 32 symptoms and ranged from 0 (absence of symptom) to 4 (severe, frequent and distressing).21, 23

On-treatment Side Effects

Three common DAA side effects and potential risk factors for non-adherence (fatigue, nausea, headache) were measured as change from baseline to treatment week 4 window using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) instruments and the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6).23–26

Statistical Analysis

All statistical estimates were computed along with corresponding 95% confidence intervals to indicate precision. Overall and subgroup-specific estimation of rates of non-adherence and SVR relied on tabulation of percentages of patients. For aims 3 and 4, multivariable logistic regression was used for both confirmatory analyses via logistic regression models specified a priori and in the investigation of potential associations and risk factors. For a priori models, logistic methods included use of Firth’s penalized likelihood approach. Covariate adjustment was used to attenuate biases due to potentially confounding factors. For the primary model of predictors of medication non-adherence, selected variables were age, sex, race, alcohol use, substance use, mental health condition, number of medical comorbidities, and DAA treatment cohort. This a priori selection was based on subgroups of primary interest (alcohol, substance use, mental health), age, race and sex, and interest in DAA treatment cohorts and number of baseline health comorbidities. For investigation of non-adherence risk factors, we used a cross-validation strategy based on data splitting and randomization to two groups. Sample 1 (n = 700) generated a set of candidate predictor variables derived from stepwise variable selection algorithms. Sample 2 (n = 862) was used to test and potentially validate the candidate models. Candidate variables using sample 2 were considered “validated” if p < 0.01. The candidate predictor variables for model building based on sample 1 included (1) sociodemographics; (2) clinical and treatment-related variables; and (3) mental health, alcohol, and substance use variables.

Analyses were performed using SAS System software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). PROMIS T scores were computed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and RStudio (RStudio Inc.).

RESULTS

Patient and Treatment Characteristics

Of the 1601 patients enrolled in PROP-UP, 1562 self-reported medication adherence during either the T2 or T3 assessment window. Among the 1513 patients with medication adherence data at T2, 65 (4%) were non-adherent, and among the 1476 patients with medication adherence data at T3, 119 (8%) were non-adherent. A total of 1447 patients provided either T2 and/or T3 medication adherence data; of these, 162 (11%) were non-adherent at either T2 and/or T3, and 88 (6%) changed from adherent to non-adherent status from T2 to T3. Among those 1447, 37% had mental health condition, 15% reported current alcohol use, and 23% reported prescription or non-prescription drug use in the last year.

Table 1 shows baseline patient characteristics stratified by non-adherence at T2 and/or T3 (n = 162) and adherence (n = 1285). The two strata exhibited notable differences in patient characteristics for age, sex, race, income, treatment cohort, and alcohol use (22% vs. 14%). The non-adherent patients exhibited a higher proportion of female patients (52% vs. 43%), black patients (43% vs. 31%), and patients with an annual income less than $40,000 (83% vs. 73%).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics by Adherence

| Characteristic | Total cohort* (n = 1562) | Adherence cohort (n = 1447) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-adherent patients† (n = 162) | Adherent patients‡ (n = 1285) | ||

| n (%) | |||

| Sociodemographic features | |||

| Age (median (IQR), mean (SD))|| | 60 (54–65) | 58 (49–63) | 60 (54–65) |

| 58 (11) | 55 (12) | 58 (10) | |

| < 35 | 87 (6) | 16 (10) | 61 (5) |

| 35–55 | 375 (24) | 48 (30) | 300 (23) |

| > 55 | 1100 (70) | 98 (60) | 924 (72) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 696 (45) | 84 (52) | 553 (43) |

| Male | 866 (55) | 78 (48) | 732 (57) |

| Race | |||

| Black | 505 (32) | 70 (43) | 401 (31) |

| White | 957 (62) | 76 (47) | 805 (63) |

| Other§ | 94 (6) | 16 (10) | 75 (6) |

| Education | |||

| Up to high school diploma or GED | 832 (54) | 78 (49) | 691 (54) |

| Vocational school or higher | 713 (46) | 82 (51) | 580 (46) |

| Annual income | |||

| Under $40,000 per year | 1133 (74) | 131 (83) | 911 (73) |

| $40,000 or above per year | 391 (26) | 27 (17) | 341 (27) |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | |||

| High | 843 (55) | 90 (57) | 694 (55) |

| Low | 688 (45) | 69 (43) | 564 (45) |

| Employment | |||

| Working full- or part-time | 538 (36) | 55 (36) | 445 (36) |

| Unemployed | 106 (7) | 13 (9) | 84 (7) |

| Disabled/applying | 675 (45) | 70 (46) | 554 (44) |

| Retired/homemaker/student | 190 (13) | 13 (9) | 163 (13) |

| Clinical and treatment features | |||

| Genotype | |||

| 1, 4, 6 | 1276 (82) | 136 (85) | 1047 (82) |

| 2 | 136 (9) | 13 (8) | 114 (9) |

| 3 | 133 (9) | 11 (7) | 111 (9) |

| Cirrhosis status | |||

| Non-cirrhotic | 818 (53) | 91 (56) | 675 (53) |

| Cirrhotic | 736 (47) | 71 (44) | 603 (47) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |||

| < 2 | 1469 (97) | 150 (94) | 1212 (97) |

| ≥ 2 | 49 (3) | 10 (6) | 34 (3) |

| HIV | |||

| No | 1471 (97) | 145 (97) | 1214 (97) |

| Yes | 52 (3) | 5 (3) | 44 (3) |

| Treatment experience | |||

| Naive | 1135 (82) | 109 (81) | 946 (82) |

| Experienced | 255 (18) | 26 (19) | 214 (18) |

| DAA treatment cohort | |||

| SOF/LED | 979 (63) | 84 (52) | 825 (64) |

| SOF/VEL | 328 (21) | 34 (21) | 275 (21) |

| GRZ/ELB | 169 (11) | 29 (18) | 125 (10) |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV | 67 (4) | 14 (8) | 47 (4) |

| SOF/DAC | 19 (1) | 1 (1) | 13 (1) |

| Ribavirin | |||

| Without | 1358 (87) | 144 (89) | 1116 (87) |

| With | 204 (13) | 18 (11) | 169 (13) |

| DAA treatment cohort by ribavirin¶ | |||

| SOF/LED | |||

| Without ribavirin | 862 (55) | 78 (48) | 718 (56) |

| With ribavirin | 117 (7) | 6 (4) | 107 (8) |

| SOF/VEL | |||

| Without ribavirin | 310 (20) | 34 (21) | 259 (20) |

| With ribavirin | 18 (1) | 0 (0) | 16 (1) |

| GRZ/ELB | |||

| Without ribavirin | 154 (10) | 27 (17) | 116 (9) |

| With ribavirin | 15 (1) | 2 (1) | 9 (1) |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV | |||

| Without ribavirin | 18 (1) | 4 (2) | 13 (1) |

| With ribavirin | 49 (3) | 10 (6) | 34 (3) |

| SOF/DAC | |||

| Without ribavirin | 14 (1) | 1 (1) | 10 (1) |

| With ribavirin | 5 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Treatment duration | |||

| 8 weeks | 153 (10) | 17 (10) | 114 (9) |

| 12 weeks | 1286 (82) | 135 (83) | 1079 (84) |

| 16 or 24 weeks | 123 (8) | 10 (6) | 92 (7) |

| Symptom burden and medical conditions | |||

| TMSAS | |||

| < 0.2 | 427 (28) | 36 (23) | 369 (29) |

| 0.2–1.0 | 834 (54) | 84 (53) | 680 (53) |

| ≥ 1.0 | 291 (19) | 39 (25) | 229 (18) |

| Number of medical comorbidities | |||

| 0–1 | 305 (20) | 29 (18) | 250 (19) |

| 2–3 | 398 (26) | 38 (23) | 340 (27) |

| 4+ | 857 (55) | 95 (59) | 693 (54) |

| Mental health and substance use features | |||

| Mental health condition | |||

| No | 984 (63) | 97 (60) | 812 (63) |

| Yes | 572 (37) | 65 (40) | 467 (37) |

| Alcohol use¶ | |||

| No | 1326 (85) | 127 (78) | 1103 (86) |

| Yes | 229 (15) | 35 (22) | 175 (14) |

| Substance use | |||

| No | 1201 (77) | 120 (74) | 995 (78) |

| Yes | 354 (23) | 42 (26) | 284 (22) |

“n” is the number of non-missing values. The percentage (%) is based on the non-missing counts. Missing values for all the characteristics were ≤ 3%, except treatment experience was missing for 11% of patients. Missing values for adherence at T2 or T3 were 7%

SD standard deviation; IQR interquartile range; DAA direct-acting antiviral; SOF/LED sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SOF/VEL sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; GRZ/ELB grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r + DSV ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir; SOF/DAC sofosbuvir/daclatasvir; TMSAS total score for the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

*Total cohort is the patients who had medication adherence at T2 or T3

†Non-adherent patients at T2 or T3

‡Adherent patients at T2 and T3. From the total cohort of patients with medication adherence data at T2 or T3 (n = 1562), there are 1447 patients with information about adherence

§For the total cohort (n = 1562), other race includes 22% American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander; 30% multiracial/biracial; 4% Asian; and 44% not reported or unknown

||Age: min = 24, max = 86

¶Variables with significant association with medication adherence at p < α = 0.01. For binary characteristics, the test statistic was the Pearson chi-square. For non-binary characteristics, the test statistic was the extended Mantel-Haenszel statistic for one stratum

In Figure 1a, the proportions of patients who were non-adherent during T2 (early treatment) and T3 (late treatment) are characterized by mental health history, alcohol use, and substance use. At T2, the rate of non-adherence for patients with mental health conditions, substance use, and alcohol use was 5–6% and similar to patients without these characteristics (4%). Overall, non-adherence doubled at T3 from 4 to 8% and was similar for participants with and without mental health conditions and those with or without substance use. At T3, the non-adherence rate was twice as high among patients with alcohol use compared to those without (14% vs. 7%).

Figure 1.

a Proportion of patients who were non-adherent by mental health condition, alcohol use, and substance use at T2 and T3. The 95% confidence intervals were computed using the Wilson score confidence limits. Superscript letter “a”: Among the 1513 patients with medication adherence data at T2, 65 (4%) were non-adherent, and among the 1476 patients with medication adherence data at T3, 119 (8%) were non-adherent. b Proportion of patients who were non-adherent: subgroups defined by sociodemographics, treatment cohort, symptoms burden, and medical comorbidities at T2 and T3. The 95% confidence intervals were computed using the Wilson score confidence limits. Superscript letter “a”: Among the 1513 patients with medication adherence data at T2, 65 (4%) were non-adherent, and among the 1476 patients with medication adherence data at T3, 119 (8%) were non-adherent. Superscript letter “b”: For the total cohort (n = 1562), other race includes 22% American Indian, Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander; 30% multiracial/biracial; 4% Asian; and 44% not reported or unknown. DAA direct-acting antiviral; SOF/LED sofosbuvir/ledipasvir’ SOF/VEL sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; GRZ/ELB grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r + DSV ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir; SOF/DAC sofosbuvir/daclatasvir; TMSAS total score for the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale; CI confidence interval.

Figure 1b shows non-adherence stratified by additional patient and treatment characteristics: demographics, treatment duration, RBV use, TMSAS scores, and health comorbidities. At T2, the non-adherence rate was 7% in black patients and 3% in whites; otherwise, no clinically important differences were noted among any other characteristics. Compared to T2, at T3, non-adherence increased by 14% among patients younger than 35, 9% in the “other” race category and among patients with elevated baseline creatinine of (2 mg/dL), and 6% among patients who had higher baseline symptom burden (scores ≥ 1 on the TMSAS).

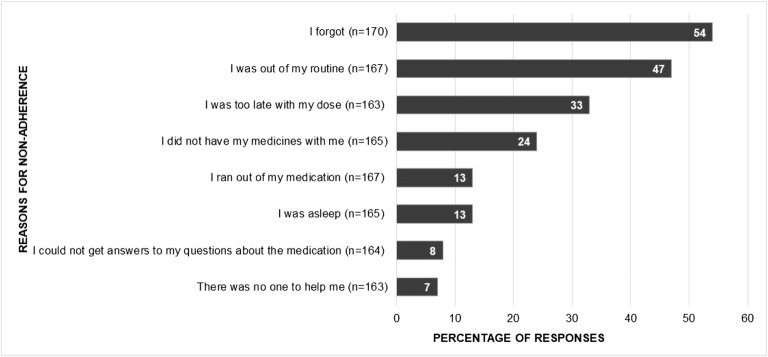

Among non-adherent patients at T2 and/or T3, the most common reasons for non-adherence were forgetfulness (54%), being out of a routine (47%), and being too late with the medication dose (33%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Reasons for non-adherence to DAA therapy. “n” is the number of responses for non-adherence reasons at T2 and T3.

Predictors of Medication Non-adherence

The multivariable model for non-adherence (Table 2) exhibited little or no association between non-adherence and substance use (OR 1.20 [95% CI 0.81, 1.78]) and mental health conditions (OR 1.02 [95% CI 0.71, 1.47]). In contrast, associations were evident for alcohol use (OR 1.96 [95% CI 1.27, 3.01]) and for age, race, number of health comorbidities, and DAA cohort. Compared to patients treated with SOF/LED, two other treatment cohorts exhibited higher rates of non-adherence: OBV/PTV/r + DSV (OR 2.04 [95% CI 1.27–3.27]) and GRZ/ELB (OR 2.80 [95% CI 1.44–5.46]). Cirrhosis, treatment experience, and RBV were not selected in the multivariable models.

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Model Predicting Medication Non-adherence

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| < 35 vs. > 55 | 3.40 | 1.78, 6.50 | p = 0.0002 |

| 35–55 vs. > 55 | 1.68 | 1.14, 2.47 | p = 0.0089 |

| Sex | |||

| Female vs. male | 1.45 | 1.03,2.04 | p = 0.0341 |

| Race | |||

| Black vs. white | 2.42 | 1.31, 4.45 | p = 0.0045 |

| Other* vs. white | 2.26 | 1.55, 3.28 | p = 0.0000 |

| DAA treatment cohort | |||

| SOF/VEL vs. SOF/LED | 1.40 | 0.90, 2.16 | p = 0.1357 |

| GRZ/ELB vs. SOF/LED | 2.80 | 1.44, 5.46 | p = 0.0025 |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV vs. SOF/LED | 2.04 | 1.27, 3.27 | p = 0.0032 |

| SOF/DAC vs. SOF/LED | 0.78 | 0.13, 4.80 | p = 0.7911 |

| Number of medical comorbidities† | |||

| Count +1 vs. count | 1.07 | 1.02, 1.13 | p = 0.0065 |

| Mental health condition | |||

| Yes vs. no | 1.02 | 0.71, 1.47 | p = 0.9098 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Yes vs. no | 1.96 | 1.27, 3.01 | p = 0.0022 |

| Substance use | |||

| Yes vs. no | 1.20 | 0.81, 1.78 | p = 0.3697 |

OR odds ratio; CI confidence interval; DAA direct-acting antiviral; SOF/LED sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SOF/VEL sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; GRZ/ELB grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r + DSV ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir; SOF/DAC sofosbuvir/daclatasvir

*For the total cohort (n = 1562), other race includes 22% American Indian, Alaskan Native, and Pacific Islander; 30% multiracial/biracial; 4% Asian; and 44% not reported or unknown

†Number of medical comorbidities is a continuous predictor

Exploration of Differences Among DAA Treatment Cohorts

We explored differences in non-adherence among DAA treatment cohorts in terms of patient characteristics stratified by DAA therapy (Table 3). Additional information on DAA regimens used, pill burden, and indications is shown in Online Appendix Table 1. Proportions of non-adherence by DAA therapy cohort are reported in Online Appendix Table 2. Patients treated with GRZ/ELB were more likely to be black, have low income, be disabled, or report a higher number of health comorbidities than those treated with SOF-containing regimens or OBV/PTV/r + DSV. Nearly one third of GRZ/ELB-treated patients reported current or past kidney disease and 20% had baseline serum creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL compared to a minority of patients treated with SOF-containing regimens or OBV/PTV/r + DSV. Patients treated with OBV/PTV/r + DSV were more likely to be white, were less likely to be treatment experienced (8% with OBV/PTV/r + DSV compared to 19–21% with other regimens), and, expectedly, were much more likely to be treated with RBV. Patients treated with OBV/PTV/r + DSV patients were more likely to report mental health conditions and alcohol use. Patient characteristics stratified by adherence versus non-adherence are found in Online Appendix Table 3.

Table 3.

Baseline Patient Characteristics by DAA Therapy Cohort and Adherence

| Characteristic | SOF/LED + SOF/VEL + SOF/DAC | GRZ/ELB | OBV/PTV/r + DSV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort (n = 1326) | Cohort (n = 169) | Cohort (n = 67) | |

| n (%) | |||

| Sociodemographic features | |||

| Age | |||

| < 35 | 71 (5) | 7 (4) | 9 (13) |

| 35–55 | 317 (24) | 40 (24) | 18 (27) |

| > 55 | 938 (71) | 122 (72) | 40 (60) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 587 (44) | 78 (46) | 31 (46) |

| Male | 739 (56) | 91 (54) | 36 (54) |

| Race | |||

| Black or African American | 406 (31) | 83 (49) | 16 (24) |

| White | 830 (63) | 78 (46) | 49 (73) |

| Other | 85 (6) | 7 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Education | |||

| Up to high school diploma or GED | 702 (54) | 95 (57) | 35 (52) |

| Vocational school or higher | 608 (46) | 73 (43) | 32 (48) |

| Annual income | |||

| Under $40,000 per year | 945 (73) | 138 (83) | 50 (75) |

| $40,000 or above per year | 345 (27) | 29 (17) | 17 (25) |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | |||

| High | 726 (56) | 81 (48) | 36 (54) |

| Low | 570 (44) | 87 (52) | 31 (46) |

| Employment | |||

| Working full- or part-time | 476 (37) | 31 (19) | 31 (47) |

| Unemployed | 92 (7) | 10 (6) | 4 (6) |

| Disabled/applying | 544 (43) | 103 (63) | 28 (42) |

| Retired/homemaker/student | 167 (13) | 20 (12) | 3 (5) |

| Clinical and treatment features | |||

| Genotype | |||

| 1, 4, 6 | 1042 (79) | 167 (100) | 67 (100) |

| 2 | 136 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 133 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Cirrhosis status | |||

| No | 695 (53) | 90 (54) | 33 (49) |

| Yes | 625 (47) | 77 (46) | 34 (51) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | |||

| < 2 | 1271 (99) | 133 (80) | 65 (98) |

| ≥ 2 | 14 (1) | 34 (20) | 1 (2) |

| Current or past kidney disease | |||

| No | 1221 (94) | 119 (71) | 64 (98) |

| Yes | 76 (6) | 48 (29) | 1 (2) |

| HIV | |||

| No | 1250 (97) | 162 (96) | 59 (98) |

| Yes | 45 (3) | 6 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Treatment experience | |||

| Naïve | 967 (81) | 112 (79) | 56 (92) |

| Experienced | 221 (19) | 29 (21) | 5 (8) |

| Ribavirin | |||

| Without | 1186 (89) | 154 (91) | 18 (27) |

| With | 140 (11) | 15 (9) | 49 (73) |

| Treatment duration | |||

| 8 weeks | 152 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| 12 weeks | 1070 (81) | 158 (93) | 58 (87) |

| 16 or 24 weeks | 104 (8) | 11 (7) | 8 (12) |

| Symptom burden and medical conditions | |||

| TMSAS | |||

| < 0.2 | 367 (28) | 38 (22) | 22 (33) |

| 0.2–1 | 714 (54) | 93 (55) | 27 (41) |

| ≥ 1 | 236 (18) | 38 (22) | 17 (26) |

| Number of medical comorbidities | |||

| 0–1 | 272 (21) | 17 (10) | 16 (24) |

| 2–3 | 346 (26) | 31 (18) | 21 (31) |

| 4+ | 706 (53) | 121 (72) | 30 (45) |

| Mental health and substance use features | |||

| Mental health condition | |||

| No | 835 (63) | 116 (69) | 33 (49) |

| Yes | 486 (37) | 52 (31) | 34 (51) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| No | 1127 (85) | 146 (87) | 53 (79) |

| Yes | 193 (15) | 22 (13) | 14 (21) |

| Substance use | |||

| No | 1015 (77) | 131 (78) | 55 (82) |

| Yes | 304 (23) | 38 (22) | 12 (18) |

DAA direct-acting antiviral; SOF/LED sofosbuvir/ledipasvir; SOF/VEL sofosbuvir/velpatasvir; GRZ/ELB grazoprevir/elbasvir; OBV/PTV/r + DSV ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir; SOF/DAC sofosbuvir/daclatasvir; TMSAS total score for the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

Predictors of Non-adherence with Clinical Follow-up

Among the 1562 patients enrolled in PROP-UP, 262 (17%) were non-adherent with clinical follow-up and had no SVR lab data after treatment completion despite multiple attempts. A multivariable model predicting non-adherence with clinical follow-up is shown in Table 4. Patients who were younger (age < 35 vs. > 55, OR 2.56 [95% CI 1.50–4.37]; age 35–55 vs. > 55, OR 1.87 [95% CI 1.37–2.54]) and those with higher total baseline symptom burden (TMSAS score ≥ 1.0 vs. < 0.2, OR 2.00 [95% CI 1.25–3.21]) were more likely to be non-adherent with clinical follow-up.

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Model Predicting Clinical Follow-up Non-adherence

| Predictor | Non-adherence to follow-up |

|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] (p value) | |

| Age | |

| < 35 vs. > 55 | 2.56 [1.50, 4.37] (p = 0.0006) |

| 35–55 vs. > 55 | 1.87 [1.37, 2.54] (p = 0.0001) |

| Sex | |

| Female vs. male | 0.92 [0.69, 1.22] (p = 0.5604) |

| Race | |

| Black vs. white | 0.70 [0.37, 1.35] (p = 0.2911) |

| Other vs. white | 1.31 [0.97, 1.78] (p = 0.0770) |

| Socioeconomic status (SES) | |

| Low vs. high | 0.95 [0.72, 1.26] (p = 0.7232) |

| Cirrhosis status | |

| Yes vs. no | 0.91 [0.68, 1.22] (p = 0.5422) |

| TMSAS—symptom burden | |

| 0.2–1.0 vs. < 0.2 | 1.34 [0.94, 1.92] (p = 0.1018) |

| ≥ 1.0 vs. < 0.2 | 2.00 [1.25, 3.21] (p = 0.0041) |

| Number of medical comorbidities | |

| Count +1 vs. count | 0.97 [0.92, 1.02] (p = 0.2117) |

| Mental health condition | |

| Yes vs. no | 1.15 [0.85, 1.55] (p = 0.3749) |

| Alcohol use | |

| Yes vs. no | 1.29 [0.89, 1.88] (p = 0.1730) |

| Substance use | |

| Yes vs. no | 0.85 [0.61, 1.18] (p = 0.3276) |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, TMSAS total score for the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

Adherence and SVR

Among the 1287 participants with adherence and SVR data (82% of study sample), a total of 53 patients (4%) failed to achieve SVR. SVR rates were similar for patients with and without mental health conditions (96% for both); 95% and 96% for those with and without alcohol use; and 95% and 96% for those with and without substance use. The overall observed SVR rate was 97% (117/121) for non-adherent patients and 96% (1038/1084) for adherent patients. SVR status was not correlated with non-adherence in a bivariate analysis (phi correlation coefficient = 0.014). Multivariable models for SVR were unreliable and inconclusive due to the small number of treatment failures.

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective study of DAA non-adherence in a real-world cohort, medication non-adherence early in treatment and/or near the end of treatment was quite low (11%) but increased over time. Though the high adherence rate is consistent with recent studies, it is remarkable given the high proportion of patients with potential non-adherence risk factors such as low income (74%), mental health conditions (37%), substance use (23%), and alcohol use (15%).7, 9, 27

Non-adherence increased from early to late in treatment, particularly among patients with alcohol use, those younger than 35, and among patients with higher overall symptom burden. Alcohol consumption and misuse had previously exhibited associations with slightly lower SVR rates in the interferon and DAA eras28, 29 and lower adherence to DAAs.30, 31 Non-adherence was not higher for patients with mental health conditions or substance use. Our results support data from registration trials that included patients on OST and found them to have comparable adherence and SVR to populations without substance use.7, 8 However, our findings are in contrast to another phase 2 clinical trial, which found recent drug use as a risk factor for non-adherence, but not controlled psychiatric disease or depressive symptoms.9

We also found that non-white race was associated with non-adherence. This is interesting in light of recent national data from the Veterans Affairs that showed lower SVR rates among black and Hispanic patients.32 Race has also been shown to be a risk factor for non-adherence in the interferon era and during treatment for other chronic diseases, highlighting the need for additional support during DAA therapy.33

Apart from sociodemographics, two regimen cohorts—GRZ/ELB and OBV/PTV/r + DSV—were associated with higher rates of non-adherence compared to sofosbuvir-containing regimens. While this finding was expected in the OBV/PTV/r + DSV cohort, given the larger pill burden, use of RBV, and twice daily dosing requirements, we were surprised by the higher non-adherence in patients on GRZ/ELB, which is a single-pill once-daily regimen. We observed that higher proportions of patients receiving GRZ/ELB were black, had lower income, were disabled, and had Cr ≥ 2 mg/dL. Although patients with baseline creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL had twice the rate of non-adherence at T3 (16% vs. 8%), the small sample size of non-adherent patients did not support fitting additional models to evaluate the effect of elevated creatinine. Larger, prospective studies could evaluate this relationship further. We were somewhat surprised by the lack of association between treatment duration and non-adherence; however, in contrast to interferon, DAAs are very well tolerated and treatment duration short, potentially explaining the lack of association.

This study has several important clinical implications. Overall non-adherence to DAAs was low and SVR was high (96%), although the optimal threshold of medication adherence is not known in the DAA era. Given that mental health conditions or substance use did not affect adherence to DAA treatment or SVR in this large, diverse cohort, there is no justification to use these patient characteristics as a basis for clinicians to withhold DAA therapy or for third-party payers to deny access to HCV treatment. Patients with alcohol use were more likely to be non-adherent early in treatment and further increase in non-adherence later in treatment suggesting that point-of-care screening for alcohol use may be useful to identify patients who may require support during DAA therapy to remain adherent. Furthermore, DAA therapy represents a window of opportunity to engage HCV patients in alcohol-related treatment; a recent study showed that receipt of alcohol-related care is under-utilized in patients with HCV.34

Younger patients were also more likely to be non-adherent with medications and clinical follow-up visits, although, interestingly, SVR rates among those with complete follow-up were 100%. The association between younger age and loss to follow-up on DAA therapy was recently shown in an inner city cohort.13 This finding is important because although young patients are less likely to have advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, they may be more likely to have recent drug use and to remain as a source of infection if SVR is not achieved, which is salient in light of the ongoing opioid epidemic. For this special population, additional strategies to support follow-up with clinic visits and services embedded within substance use treatment centers may be warranted. Finally, as the most common reasons for non-adherence were forgetfulness or being out of a routine, low-cost, technology-based strategies such as text message reminders may be leveraged to support adherence.

We must acknowledge certain study limitations. Mental health, substance use, and alcohol use were all self-reported. We did not have data on drug use at baseline nor patient adherence behaviors during treatment, although assessment of alcohol use was current. We did not collect data on homelessness, men who have sex with men, or OST. The non-adherence measure was self-reported, may underestimate non-adherence, and does not reflect actual pill-taking behavior. Electronic monitoring was not feasible due to the study size. Pharmacy refill data was not practical due to short-duration regimens.35 We were unable to reliably evaluate the association between medication non-adherence and SVR due to the low rate of treatment failure; however, without accounting for confounders, the bivariate correlation was negligible. As with any observational study, bias due to confounding is a concern.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite a substantial prevalence of mental health conditions, alcohol use, and substance use, DAA non-adherence was low and SVR was high. Psychosocial comorbidities should not serve as a basis for DAA denials either by clinicians or insurance payers. Simple, low-cost solutions such as point-of-care testing for alcohol use and concurrent treatment support, education about the importance of adherence, and medication reminder strategies may promote DAA adherence and appropriate long-term clinical follow-up.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 37 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following people: The UNC Patient Engagement Group; Shani Alston, La-Shell Johnson, Virginia Sharpless, Ken Berquist, Herleesha Anderson, Courtenay Pierce, Jenn Barr, Bryonna Jackson, Drew Foreman, Jane Giang, Jama Darling, Paul Hayashi, Steven Zacks, A. Sidney Barritt IV, Scott Elliot, Dawn Harrison, Danielle Cardona (University of North Carolina); Patrick Horne (University of Florida); Kelly Borges, Danielle Ciuffetelli (University of Pennsylvania); Chrissy Ammons, Kathleen Genther, Jessica Mason (Virginia Commonwealth University); Lelani Fetrow, Vicki Shah (Rush University); Theresa Cattoor, Alisha McLendon (Saint Louis University); Mariechristi Candido, Sophia Zaragoza, Sandeep Dhaliwal, Patricia Poole, Rebecca Hluahanich, Kathleen Haight, (University of California, Davis); Andrea Gajos, Elizabeth Wu, Carrie Bergmans (University of Michigan); AnnMarie Liapakis, MD, Kristine Drozd, Carol Eggers, Hong Chau, and Claudia Bertuccio (Yale University); William Harlan, Roberta Golden, Kylee Diaz (Asheville Gastroenterology Associates); William King, Megan Marles (Wilmington Gastroenterology Associates). Thank you to all the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was funded through a Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award to Donna Evon (CER 1408 20660). Additional support for this study (data management) was partially supported by the NIDDK-funded Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease (P30-DK34987; PI: Sandler) and the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute NIH NCATS (Grant Number: UL1TR002489). Additional support for Dr. Golin’s salary was partially supported by the NIH Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K24 HD06920) and by the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) (P30 AI 50410). The statements presented in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Sites obtained local Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and all participants provided informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

Donna M. Evon receives research funding from Gilead and Merck (paid to UNC). Michael Fried has received research funding from and served as a consultant for AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, Merck, and TARGET PharmaSolutions. Stock in TARGET PharmaSolutions is held in an independently managed trust. Anna S. Lok has received research support from BMS, Gilead, TARGET PharmaSolutions, AbbVie, and Merck, and served as an advisor for Gilead. Richard K. Sterling has received research support from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, Merck, and Roche, and served as a consultant for Merck, Bayer, Sa2lix, AbbVie, Gilead, Jansen, ViiV, Baxter, and Pfizer. Joseph K. Lim has received research support (paid to Yale University) and served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead. Nancy Reau has received research funding (paid to Rush) from AbbVie and Intercept and has served as a consultant for Merck, AbbVie, Abbott, and Gilead. Souvik Sarkar served on a Gilead and AbbVie Advisory Board. David R. Nelson has received research grant support from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, and Merck and owns stock in TARGET PharmaSolutions. K. Rajender Reddy is an Ad-Hoc Advisor to Gilead, BMS, Janssen, Merck, and AbbVie and has received research support from Gilead, BMS, Janssen, Merck, and AbbVie (paid to the University of Pennsylvania). Adrian M. Di Bisceglie has received research support from AbbVie, BMS, and Gilead and has served on advisory boards for AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and Merck. He serves as Chair of the Steering Committee for TARGET HCC, a registry study funded by TARGET PharmaSolutions. Paul Stewart has served as a consultant to TARGET PharmaSolutions. Jipcy Amador served as a biostatistics intern at TARGET PharmaSolutions in 2017. Carol E. Golin, Marina Serper, and Bryce Reeve declare that they have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lo Re V, 3rd, Teal V, Localio AR, Amorosa VK, Kaplan DE, Gross R. Relationship between adherence to hepatitis C virus therapy and virologic outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(6):353–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-6-201109200-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AASLD-IDSA. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org. Accessed June 30, 2019.

- 3.Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis C infection. Updated version, April 2016, https://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-c-guidelines-2016/en/. Accessed June 30, 2019. [PubMed]

- 4.Millman AJ, Ntiri-Reid B, Irvin R, Kaufmann MH, Aronsohn A, Duchin JS, et al. Barriers to Treatment Access for Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Case Series. Top Antivir Med. 2017;25(3):110–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooka K, Connolly JJ, Lim JK. Medicaid Reimbursement for Oral Direct Antiviral Agents for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(6):828–32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Examining Hepatitic C Virus Treatment Access: A Review Of Select State Medicaid Fee-For-Service and Managed Care Programs. https://nvhr.org/sites/default/files/Examining%20HCV%20Treatment%20Access%20Report.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2019.

- 7.Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, Dalgard O, Gane EJ, Shibolet O, et al. Elbasvir-Grazoprevir to Treat Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Persons Receiving Opioid Agonist Therapy: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):625–34. doi: 10.7326/M16-0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grebely J, Feld JJ, Wyles D, Sulkowski M, Ni L, Llewellyn J, et al. Sofosbuvir-Based Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapies for HCV in People Receiving Opioid Substitution Therapy: An Analysis of Phase 3 Studies. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(2):ofy001. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petersen T, Townsend K, Gordon LA, Sidharthan S, Silk R, Nelson A, et al. High adherence to all-oral directly acting antiviral HCV therapy among an inner-city patient population in a phase 2a study. Hepatol Int. 2016;10(2):310–9. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9680-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butner JL, Gupta N, Fabian C, Henry S, Shi JM, Tetrault JM. Onsite treatment of HCV infection with direct acting antivirals within an opioid treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;75:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason K, Dodd Z, Guyton M, Tookey P, Lettner B, Matelski J, et al. Understanding real-world adherence in the directly acting antiviral era: A prospective evaluation of adherence among people with a history of drug use at a community-based program in Toronto. Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yek C, de la Flor C, Marshall J, Zoellner C, Thompson G, Quirk L, et al. Effectiveness of direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C in difficult-to-treat patients in a safety-net health system: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0969-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kattakuzhy S, Gross C, Emmanuel B, Teferi G, Jenkins V, Silk R, et al. Expansion of Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection by Task Shifting to Community-Based Nonspecialist Providers: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):311–8. doi: 10.7326/M17-0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evon DM, Golin CE, Stewart P, Fried MW, Alston S, Reeve B, et al. Patient engagement and study design of PROP UP: A multi-site patient-centered prospective observational study of patients undergoing hepatitis C treatment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;57:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pence BW, Gaynes BN, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Jr, Ryder RW, Miller WC. Validation of a brief screening instrument for substance abuse and mental illness in HIV-positive patients. JAcquirImmuneDeficSyndr. 2005;40(4):434–44. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000177512.30576.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whetten K, Reif S, Swartz M, Stevens R, Ostermann J, Hanisch L, et al. A Brief Mental Health and Substance Abuse Screener for Persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(2):89–99. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voils CI, Maciejewski ML, Hoyle RH, Reeve BB, Gallagher P, Bryson CL, et al. Initial validation of a self-report measure of the extent of and reasons for medication nonadherence. Med Care. 2012;50(12):1013–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318269e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voils CI, King HA, Thorpe CT, Blalock DV, Kronish IM, Reeve BB, et al. Content Validity and Reliability of a Self-Report Measure of Medication Nonadherence in Hepatitis C Treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(10):2784–2797. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, Lepore JM, Friedlander-Klar H, Kiyasu E, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A(9):1326–36. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Thaler HT, Kasimis BS, Portenoy RK. Memorial symptom assessment scale. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2004;4(2):171–8. doi: 10.1586/14737167.4.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evon DM, Amador J, Stewart P, Reeve BB, Lok AS, Sterling RK, et al. Psychometric properties of the PROMIS short form measures in a U.S. cohort of 961 patients with chronic hepatitis C prescribed direct acting antiviral therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(7):1001–11. doi: 10.1111/apt.14531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(11):1179–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE, Jr, Garber WH, Batenhorst A, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):963–74. doi: 10.1023/A:1026119331193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Cook KF, Crane PK, Teresi JA, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S22–31. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, Nader F, Younossi Y, Hunt S. Adherence to treatment of chronic hepatitis C: from interferon containing regimens to interferon and ribavirin free regimens. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(28):e4151. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell M, Pauly MP, Moore CD, Chia C, Dorrell J, Cunanan RJ, et al. The impact of lifetime alcohol use on hepatitis C treatment outcomes in privately insured members of an integrated health care plan. Hepatology. 2012;56(4):1223–30. doi: 10.1002/hep.25755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsui JI, Williams EC, Green PK, Berry K, Su F, Ioannou GN. Alcohol use and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes among patients receiving direct antiviral agents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;169:101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akiyama MJ, Norton BL, Arnsten JH, Agyemang L, Heo M, Litwin AH. Intensive Models of Hepatitis C Care for People Who Inject Drugs Receiving Opioid Agonist Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Butt AA, Yan P, Shaikh OS, Chung RT, Sherman KE. study E. Treatment adherence and virological response rates in hepatitis C virus infected persons treated with sofosbuvir-based regimens: results from ERCHIVES. Liver Int. 2016;36(9):1275–83. doi: 10.1111/liv.13103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su F, Green PK, Berry K, Ioannou GN. The association between race/ethnicity and the effectiveness of direct antiviral agents for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2017;65(2):426–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.28901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conjeevaram HS, Fried MW, Jeffers LJ, Terrault NA, Wiley-Lucas TE, Afdhal N, et al. Peginterferon and ribavirin treatment in African American and Caucasian American patients with hepatitis C genotype 1. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(2):470–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owens MD, Ioannou GN, Tsui JL, Edelman EJ, Greene PA, Williams EC. Receipt of alcohol-related care among patients with HCV and unhealthy alcohol use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang PS, Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Winkelmayer WC, Mogun H, Avorn J. How well do patients report noncompliance with antihypertensive medications?: a comparison of self-report versus filled prescriptions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(1):11–9. doi: 10.1002/pds.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 37 kb)