Abstract

Background and Purpose

Breast cancer is the leading cause of death in women worldwide, with resistance to current therapeutic strategies, including tamoxifen, causing major clinical challenges and leading to more aggressive and metastatic disease. To address this, novel strategies that can inhibit the mechanisms responsible for tamoxifen resistance need to be assessed.

Experimental Approach

We examined the effect of the novel, clinically‐trialled, thiosemicarbazone anti‐cancer agent, DpC, and its potential as a combination therapy with the clinically used estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist, tamoxifen, using both tamoxifen‐resistant and ‐sensitive, human breast cancer cells (MDA‐MB‐453, MDA‐MB‐231 and MCF‐7) in 2D and 3D cell‐culture. Synergy was assessed using the Chou‐Talalay method. The molecular and anti‐proliferative effects of these agents and their combination was examined via Western blot, immunofluorescence and colony formation assays.

Key Results

Combinations of tamoxifen with DpC were highly synergistic, leading to potent inhibition of cell proliferation, colony formation, and ER‐α transcriptional activity. The combination also more efficiently reduced major molecular drivers of proliferation of tamoxifen‐resistant cells, including c‐Myc, cyclin D1, and p‐AKT, while up‐regulating the cell cycle inhibitor, p27, and inhibiting oncogenic phosphorylation of ER‐α at Ser167. Assessing these effects using 3D cell culture further confirmed the greater effects of DpC combined with tamoxifen in reducing ER‐α expression, and that of the proliferation marker, Ki‐67, in both tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 spheroids.

Conclusions and Implications

These studies demonstrate that the synergistic combination of DpC with tamoxifen could be a promising new therapeutic strategy to overcome tamoxifen resistance in ER‐positive breast cancer.

Abbreviations

- 4‐OHT

4‐hydroxy‐tamoxifen

- CI

combination index

- DpC

di‐2‐pyridylketone 4‐cyclohexyl‐4‐methyl‐3‐thiosemicarbazone

- EGFR

EGF receptor

- ER

oestrogen receptor

- EREs

oestrogen response elements

- IGF1R

insulin‐like growth factor 1 receptor

What is already known

Tamoxifen resistance is a major clinical problem, leading to development of aggressive, metastatic breast cancers.

Intrinsic and ligand‐independent mechanisms of ER‐α activation drive development of tamoxifen resistance.

What this study adds

The novel clinically trialled anti‐cancer agent DpC inhibits major pathways that drive ligand‐independent ER‐α activation.

Combining DpC with tamoxifen demonstrates potent synergy and overcomes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer.

What is the clinical significance

Combining DpC with tamoxifen may overcome tamoxifen resistance, preventing onset of more aggressive breast cancer.

These findings are highly significant, as 20% of ER‐positive breast cancer patients develop tamoxifen resistance.

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer‐related deaths, affecting 2.1 million women each year (Ali et al., 2016). The oestrogen receptor‐α (https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=620) is expressed in 75% of breast cancer cases (Zhang, Man, Zhao, Dong, & Ma, 2014) and is a ligand‐responsive transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in driving breast cancer progression (Hayashi et al., 2003). The orthodox genomic ER‐α pathway entails https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=1013 (E2) binding to ER‐α, resulting in dimerization and nuclear localization, where it binds to oestrogen response elements (EREs) to promote transcription responsible for growth, proliferation, and metastasis (Acconcia & Kumar, 2006; Klinge, 2001).

Therapies for ER‐positive breast cancer include selective ER modulators, with https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=1016 being the standard of care for younger women with breast cancer (Osborne, 1998). Tamoxifen binds ER‐α, blocking its ability to bind EREs (Obrero, Yu, & Shapiro, 2002). However, 20% of all ER‐positive breast cancer develop resistance to tamoxifen, leading to more aggressive neoplasms (Ali et al., 2016; Ring & Dowsett, 2004). Several mechanisms drive tamoxifen resistance, including the interaction of ER‐α with growth factors, such as https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=4916 and/or the over‐expression of human EGF receptors (i.e., https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=1797 and https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2019), activating downstream https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/FamilyDisplayForward?familyId=512 and https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2503/https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2286 pathways (Campbell et al., 2001; Fan, Wang, Santen, & Yue, 2007; Ghayad et al., 2010; Osborne, Shou, Massarweh, & Schiff, 2005; Riggins, Schrecengost, Guerrero, & Bouton, 2007). This enables ligand‐independent phosphorylation of ER‐α at Ser118 and Ser167 (Campbell et al., 2001; Ghayad et al., 2010; Kato et al., 1995; Sun et al., 2001), promoting c‐Myc and cyclin D1 expression (Ali et al., 2016; Green et al., 2016; Kilker, Hartl, Rutherford, & Planas‐Silva, 2004; Santen et al., 2009). In fact, over‐expression or activation of these latter proteins is extensively linked to tamoxifen resistance (Santen et al., 2009), and it is critical to develop novel strategies to inhibit or prevent resistance.

We synthesized the novel thiosemicarbazone, di‐2‐pyridylketone 4‐cyclohexyl‐4‐methyl‐3‐thiosemicarbazone (DpC), which has potent and selective anti‐cancer activity against multiple neoplasms in vitro and in vivo (Guo et al., 2016; Kovacevic, Chikhani, Lovejoy, & Richardson, 2011; Lovejoy et al., 2012). DpC binds iron and copper to form redox‐active complexes that are cytotoxic to cancer cells (Lane, Saletta, Suryo Rahmanto, Kovacevic, & Richardson, 2013) and up‐regulates the metastasis suppressor, N‐myc downstream regulated gene‐1 (Kovacevic et al., 2011). Following extensive pharmacokinetic and toxicity studies (Kovacevic et al., 2011; Lovejoy et al., 2012; Sestak et al., 2015), DpC entered Phase I clinical trials to assess its efficacy in advanced cancers (Jansson et al., 2015).

Importantly, DpC decreases the expression of key EGF receptors including EGFR, HER2, and HER3 (Kovacevic et al., 2011), while inhibiting downstream PI3K/AKT and MAPK signalling (Kovacevic et al., 2011; Kovacevic et al., 2016; Lui et al., 2015; Xi et al., 2017). As these pathways play major roles in tamoxifen resistance (Butt, McNeil, Musgrove, & Sutherland, 2005; Ghayad et al., 2010; Kato et al., 1995; Riggins et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2001), DpC may overcome this major clinical problem.

Considering this, we examined the role of DpC and its potential for synergy with tamoxifen in ER‐positive breast cancer. We have demonstrated that DpC combined with the active tamoxifen metabolite, 4‐hydroxy‐tamoxifen (4‐OHT), down‐regulates key oncogenes, including p‐AKT, c‐Myc, and cyclin D1, while potently inhibiting proliferation and colony formation of tamoxifen‐resistant and ‐sensitive MCF‐7 cells. Hence, the combination of DpC with tamoxifen has the potential to overcome tamoxifen resistance and prevent the progression of breast cancer.

2. METHODS

2.1. Cell culture

The human breast cancer cell lines, MCF‐7 (RRID:CVCL_0031), T47D (RRID:CVCL_0553), MDA‐MB‐453 (RRID:CVCL_0418), and MDA‐MB‐231 (RRID:CVCL_0062), were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cells were grown in MEM complete media (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% FCS (ThermoFisher Scientific). Tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells (resistant) and their sensitive vehicle control counterparts (sensitive) were generated (Knowlden et al., 2003) and generously provided by Dr. Elizabeth Caldon (Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney). The resistant cells were generated by continuous incubation with the active metabolite of tamoxifen, namely, 4‐OHT, for 6 months (Knowlden et al., 2003). All cells were authenticated based on viability, recovery, growth, morphology, and cytogenetic analysis (i.e., antigen expression, DNA profile, and iso‐enzymology) by the provider.

The cell lines were maintained in phenol red‐free RPMI media (ThermoFisher Scientific), supplemented with 5% (v/v) charcoal‐stripped serum (csFBS; Sigma‐Aldrich; MO, USA) and 100 μg·ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine (ThermoFisher Scientific). Resistant cells were grown in 10 μM 4‐OHT (re‐suspended in tetrahydrofuran) along with 10 pM β‐E2 (re‐suspended in ethanol). Sensitive cells were maintained in base media with 10 μM of tetrahydrofuran and 10 pM of ethanol. Cells were grown in an incubator at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. For studies assessing the effects of E2 and EGF, cells were incubated with phenol‐red free media containing 5% csFBC for 3 days prior to treatment with E2 and EGF at concentrations of 10 nM and 100 ng·ml−1, respectively, for 10 min/37°C.

2.2. MTT assay

Both tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells were seeded in 96‐well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with DpC or 4‐OHT at a range of concentrations (0–1.25 μM for DpC and 0–40 μM for 4‐OHT) and incubated for a further 72 hr. Proliferation was examined using the 3‐(4,5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2,5‐diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT; Sigma‐Aldrich) assay, using standard methods (Richardson, Tran, & Ponka, 1995). As shown previously, MTT colour formation was directly proportional to viable cell number (Richardson et al., 1995).

2.3. Chou–Talalay combination analysis

For the combination studies with DpC and 4‐OHT, the Chou–Talalay method was used (Chou, 2006; Chou, 2010). The resulting combination index (CI) offers a quantitative definition for an additive effect, where synergism is evident when CI < 1 and antagonism when CI > 1 in drug combinations (Chou, 2010). Briefly, to calculate the CI and dose reduction index, cells were incubated with DpC and 4‐OHT in a range that was eight times below, and eight times above, their respective IC50 values after a 72 hr/37°C incubation (i.e., 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 × IC50). The concentrations of DpC and 4‐OHT used were cell type dependent, as each cell line had its own IC50 values for these agents. The resulting dose–response curves were then analysed using Chou–Talalay methodology (Chou, 2006; Chou, 2010).

2.4. Protein extraction, Western blot, and antibodies

The antibody‐based procedures used in this study comply with the recommendations made by the British Journal of Pharmacology. Following treatment with either control, DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) for 24 hr/37°C, cells were then harvested and protein extracted using standard methods (Chen et al., 2012). Western blot analysis was performed via established methods (Gao & Richardson, 2001). The primary antibodies used (diluted at 1:1,000) included ER‐α (RRID:AB_2632959), p‐ER‐α (Ser167; RRID:AB_2102074), EGFR (RRID:AB_2262057), p‐EGFR (Tyr1068; RRID:AB_1903957), AKT (RRID:AB_329827), p‐AKT (Ser473; RRID:AB_329824), c‐Myc (RRID:AB_2151827), p‐c‐Myc (Ser62; RRID:AB_2151830), cyclin D1 (RRID:AB_2228523), p27 (RRID:AB_10693314), SRC3 (RRID:AB_823642), NF‐κB‐p65 (RRID:AB_2341215), and p‐NF‐κB‐p65 (Ser536; RRID:AB_331281; Cell Signaling Technology, MA); β‐actin (diluted at 1:10,000, RRID:AB_476692) was purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. The secondary antibodies implemented (diluted 1:10,000) include anti‐rabbit and anti‐mouse antibodies (Sigma‐Aldrich; RRID:AB_2336059, RRID:AB_2336060).

2.5. Spheroid generation and immunofluorescence

Spheroids were prepared by seeding 35,000 cells per well in phenol red‐free RPMI supplemented with 5% csFBS and 100 μg·ml−1 penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine in 96‐well plates coated with 0.75% (w/v) agarose. The plates were then incubated for 3–4 days/37°C in 5% CO2. Once established, spheroids were treated with either 5‐μM DpC, 5‐μM 4‐OHT, or these agents combined at 5 μM each (combination) for a further 24 hr/37°C. Spheroids were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 hr/20°C. Following fixation, spheroids were washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100, and blocked using 5% BSA in PBS overnight at 4°C. They were then incubated with either mouse Ki‐67 (RRID:AB_2797703) or rabbit ER‐α monoclonal antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. After washing 3 × 10 min with PBS, secondary antibodies (anti‐mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 488 [RRID:AB_10694704] and anti‐rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 594 [RRID:AB_2716249]; Cell Signaling Technology) were added at 1:200 dilution in BSA buffer for 1 hr/20°C. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Life Technologies), and spheroids imaged and photographed using a META confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany). Intensity analysis was performed using Fiji ImageJ software (NIH, Baltimore, MD; RRID:SCR_003070).

2.6. Colony formation assay

MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells were harvested and plated (70 cells per plate) in 100‐mm Petri dishes for 21 days with media containing either DpC (0.125 μM), 4‐OHT (0.125 μM), or their combination at 0.125 μM each. Colonies were then rinsed with 10‐ml PBS, fixed (acetic acid/methanol [1:7 v/v]), and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. After staining, colonies were visualized and examined microscopically.

2.7. Dual‐luciferase assay for ER‐α

The ERE Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Cignal Reporter Assay Kit; Qiagen, Netherlands) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, the MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells were transfected with the ERE Luciferase Reporter, as well as the relevant positive and negative controls for 48 hr. Cells were then incubated with either DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each), in the presence of E2 for a further 24 hr. Luciferase activity was then assessed implementing the Dual‐Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Cat. No. 1910; Promega) using a luminometer (FLUOstar; BMG Labtech, Germany).

2.8. Densitometry

Densitometry was performed using Quantity One software (Bio‐Rad; CA; RRID:SCR_014280) and normalized using the β‐actin loading control.

2.9. Data and statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. The group data subjected to statistical analysis have a minimum of n = 5 independent samples per group. Statistical comparisons between two groups were evaluated by the unpaired Student's t test and were considered significant when P < .05. The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations of the British Journal of Pharmacology on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2018). To provide blinding in our experiments, analysis of the experimental data was performed by different people to those that completed the experiment. All studies were designed to provide randomization, with cells being randomly assigned to different treatment groups.

2.10. Materials

DpC was synthesized as described previously (Lovejoy et al., 2012). 4‐OHT was supplied by Sigma‐Aldrich (MO, USA) and EGF was supplied by Cell Signaling Technology (MA, USA).

2.11. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (RRID:SCR_013077; Harding et al., 2018), and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 (Alexander, Cidlowski et al., 2019; Alexander, Fabbro et al., 2019a, 2019b).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Assessing the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT in breast cancer cells

The novel anti‐cancer agent, DpC, and its potential to synergize with the active metabolite of tamoxifen, https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=2817, was assessed using well‐characterized ER‐a positive (MCF‐7 and T47D) and ER‐a negative (MDA‐MB‐231 and MDA‐MB‐453) breast cancer cells (Miller & Katzenellenbogen, 1983; Vranic, Gatalica, & Wang, 2011).

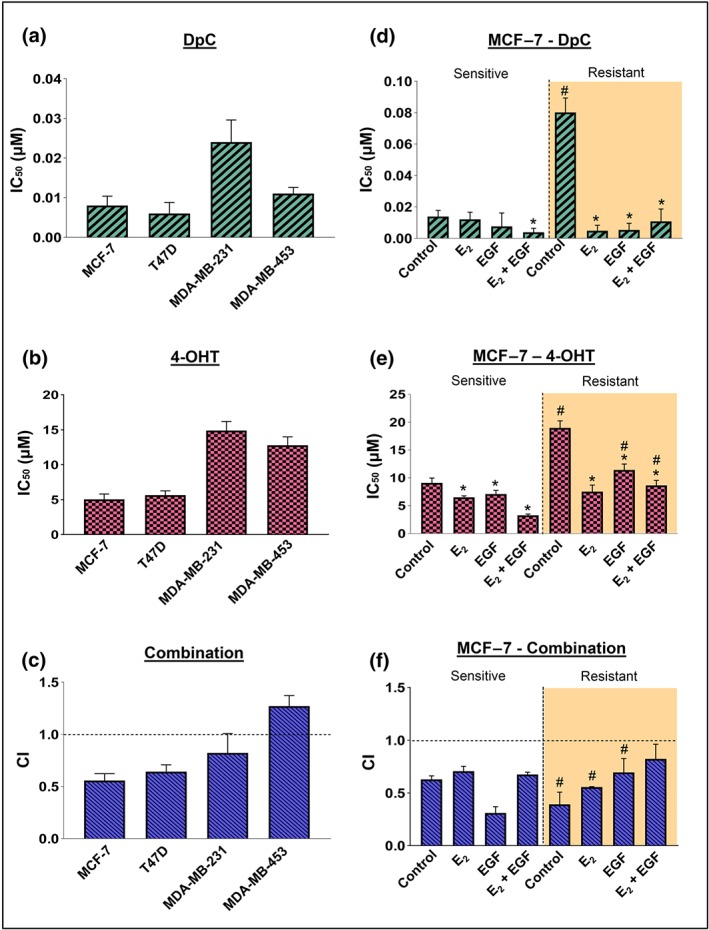

DpC substantially inhibited proliferation of all breast cancer cells examined, with IC50 values (72 hr) ranging from 0.006 to 0.024 μM (Figure 1a). ER‐positive breast cancer cells (T47D and MCF‐7) were most sensitive, while triple‐negative MDA‐MB‐231 cells were least sensitive to DpC (Figure 1a). 4‐OHT alone displayed much higher IC50 values than DpC, ranging from 7 to 14 μM (72 hr; Figure 1b). As expected, ER‐positive cells were two to three times more sensitive to 4‐OHT compared to ER‐negative cells (MDA‐MB‐453 and MDA‐MB‐231; Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

The combination of DpC and 4‐OHT is synergistic in ER‐positive breast cancer cells. IC50 values for (a) DpC and (b) 4‐OHT in MCF‐7, T47D, MDA‐MB‐231, and MDA‐MB‐453 breast cancer cells. (c) Combination index (CI) values of DpC in combination with 4‐OHT in MCF‐7, T47D, MDA‐MB‐231, and MDA‐MB‐453 breast cancer cells. IC50 values for (d) DpC and (e) 4‐OHT in MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells in the presence of control media or media containing E2, EGF, or both. (f) CI values of DpC combined with 4‐OHT in MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells in control media or media containing E2, EGF, or both. Data represent the mean ± SD of five independent experiments. *P < .05, significantly different from the respective control; # P < .05, significantly different from the corresponding treatment in MCF‐7‐sensitive cells

Next, we examined the potential synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT using the Chou–Talalay method (Chou, 2010). For ER‐positive MCF‐7 and T47D cells, the combination of DpC with 4‐OHT was highly synergistic (Figure 1c). In contrast, the ER‐negative MDA‐MB‐231 and MDA‐MB‐453 cells had CI values close to or >1, indicating no synergism (Figure 1c). These results suggest that the combination of DpC and 4‐OHT was synergistic only in ER‐positive breast cancer cells.

3.2. Assessing synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells

We next investigated the potential of combining DpC with 4‐OHT in overcoming tamoxifen resistance in ER‐positive cells using tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 (resistant) cells and their sensitive counterparts (sensitive; Knowlden et al., 2003). MTT studies were conducted to assess the IC50 values of each agent in these cells under different conditions, including (a) no ligands, (b) E2 alone (10 nM), (c) EGF alone (100 ng·ml−1), or (d) E2 (10 nM) and EGF (100 ng·ml−1) together, for 72 hr. This was done as E2 or EGF can activate ER‐α, with EGF also promoting tamoxifen resistance (Ghayad et al., 2010; Knowlden et al., 2003).

Tamoxifen‐sensitive MCF‐7 cells were highly sensitive to DpC under all conditions assessed, with IC50 values <0.02 μM (Figure 1d). Tamoxifen‐resistant cells had significantly higher IC50 values for DpC in the absence of ligands, although sensitivity was restored upon addition of E2, EGF, or their combination (Figure 1d). The IC50 values for 4‐OHT in the sensitive cells (Figure 1e) were up to 100‐fold higher compared to DpC (Figure 1d). As expected, the IC50 values for 4‐OHT in the resistant cells were significantly higher, or slightly higher (i.e., for E2), when compared to their sensitive counterparts (Figure 1e). However, in the presence of E2, EGF, or their combination, the resistant cells also became significantly more sensitive to 4‐OHT compared with the control (Figure 1e).

For both sensitive and resistant cells, a synergistic effect was observed when DpC and 4‐OHT were combined at the same dose ratios, with CI values <1 under all conditions (Figure 1f). Notably, synergy was more pronounced in control and E2‐treated resistant cells when compared with their sensitive counterparts. Assessing CI values using different doses of DpC and 4‐OHT (Tables S1 and S2) further confirmed that these agents were synergistic in the majority of combinations. Further, dose reduction index values (Tables S1 and S2) indicated the doses of DpC and 4‐OHT could be reduced to maintain efficacy, while potentially reducing toxicity, which would be highly beneficial in clinical use. Overall, these studies demonstrate that DpC in combination with 4‐OHT exhibited a synergistic effect in ER‐α‐positive cell types.

3.3. DpC alone or in combination with 4‐OHT decreases ER‐α expression

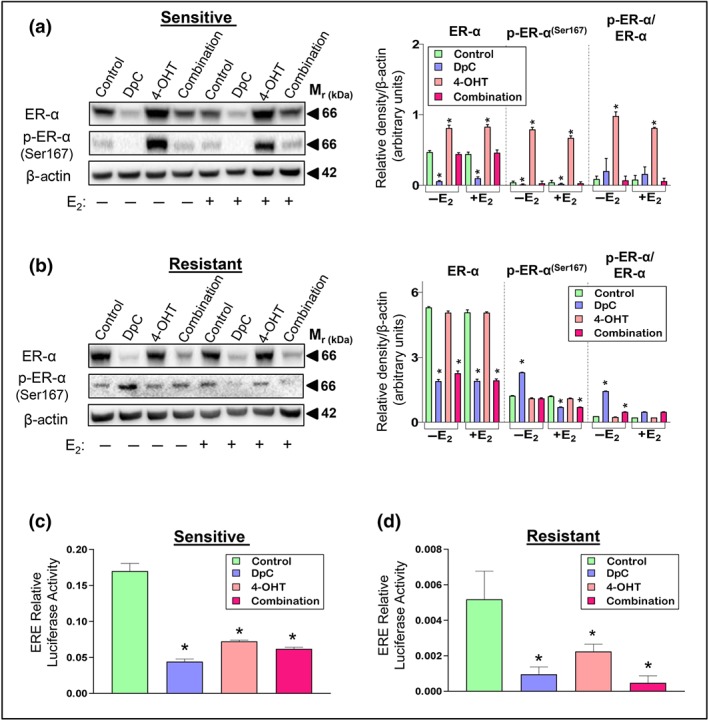

To elucidate the mechanisms underlying the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT, we next examined the effect of DpC alone or in combination with 4‐OHT on ER‐α in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells (Figure 2a,b). Both cell types were incubated for 24 hr with either DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or these agents combined (5 μM each), followed by a 10‐min incubation with or without the ER‐α activating ligand, E2 (10 nM). These doses were selected based on our studies using DpC in vitro (Kovacevic et al., 2011) and studies by others using 4‐OHT (Lee et al., 2018). The levels of total ER‐α or its phosphorylation at Ser167 (p‐ER‐α), which contributes to tamoxifen resistance (Bostner et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2001), were then assessed via Western blot.

Figure 2.

The effect of DpC, 4‐OHT, and their combination on ER‐α levels and transcriptional activity. Western blot analysis of total ER‐α and its phosphorylation at Ser167 in (a) sensitive and (b) tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells treated with either control media or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein loading control. Data represent the mean ± SD of five independent experiments. *P < .05, significantly different from the respective controls. Luciferase activity of ERE‐containing constructs in MCF‐7 (c) sensitive and (d) resistant cells treated with either control media or media containing DpC, 4‐OHT, or their combination. Data represent the mean ± SD of five independent experiments. *P < .05, significantly different from the respective control

In sensitive cells, DpC significantly down‐regulated ER‐α and p‐ER‐α (Figure 2a), while 4‐OHT markedly increased ER‐α and p‐ER‐α under all conditions (Figure 2a). This was expected, as 4‐OHT binds to ER‐α, leading to its stabilization and the inhibition of downstream signalling (Jaiyesimi, Buzdar, Decker, & Hortobagyi, 1995). Assessing the ratio of p‐ER‐α to total ER‐α for 4‐OHT demonstrated a significant increase, compared with the control, suggesting that 4‐OHT facilitated ER‐α phosphorylation (Figure 2a). In contrast, this ratio did not significantly alter for DpC relative to the control, suggesting that a decrease in ER‐α phosphorylation can be attributed to decreased total ER‐α. When DpC was combined with 4‐OHT (combination), total ER‐α and p‐ER‐α remained similar to the untreated controls under all conditions.

In resistant cells, DpC again markedly reduced total ER‐α, while 4‐OHT had no significant effect (Figure 2b). In contrast to sensitive cells (Figure 2a), DpC significantly increased p‐ER‐α in the absence of E2, while reducing its levels in the presence of E2 in resistant cells (Figure 2b). The combination of DpC with 4‐OHT in resistant cells gave similar results to DpC alone (Figure 2b).

3.4. DpC and 4‐OHT inhibit ER‐α transcriptional activity in sensitive and resistant MCF‐7 cells

Further studies assessed ER‐α transcriptional activity, as activated ER‐α can directly or indirectly bind to target gene EREs to promote breast cancer progression (Levin & Pietras, 2008). To achieve this, ERE dual‐luciferase reporter assays were performed, which was transfected into tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells followed by incubation with DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination for 24 hr.

A significant decrease in luciferase activity was observed in sensitive (Figure 2c) and resistant (Figure 2d) cells upon treatment with DpC or 4‐OHT. The combination of DpC and 4‐OHT also led to a pronounced down‐regulation of luciferase activity in sensitive and resistant cells, with the combination being most effective in resistant cells (Figure 2d).

Considering reduced ER‐α transcriptional activity, we further examined two major co‐activators of ER‐α, namely, SRC3 and NF‐κB‐p65 (Gionet, Jansson, Mader, & Pratt, 2009; Osborne et al., 2003). SRC3 was reduced by DpC and the combination in sensitive cells, while being reduced by DpC, 4‐OHT, and their combination in resistant cells (Figure S1). While total NF‐κB‐p65 was not affected by these agents in sensitive cells, DpC, 4‐OHT, and their combination reduced NF‐κB‐p65 in resistant cells. Notably, in the presence of E2, the combination treatment was most effective at reducing SRC3 and NF‐κB‐p65 levels in the resistant cells (Figure S1), demonstrating the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT. The activating phosphorylation of NF‐κB‐p65 (Ser536) was also most reduced by the combination in sensitive cells. However, its expression in the resistant cells was increased by DpC or 4‐OHT (Figure S1), which may account for the lower sensitivity of these cells to these agents alone (Figure 1d,e). Importantly, this adverse effect was prevented when resistant cells were incubated with DpC and 4‐OHT as a combination (Figure S1), further highlighting their synergy.

3.5. DpC down‐regulates AKT activation in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells

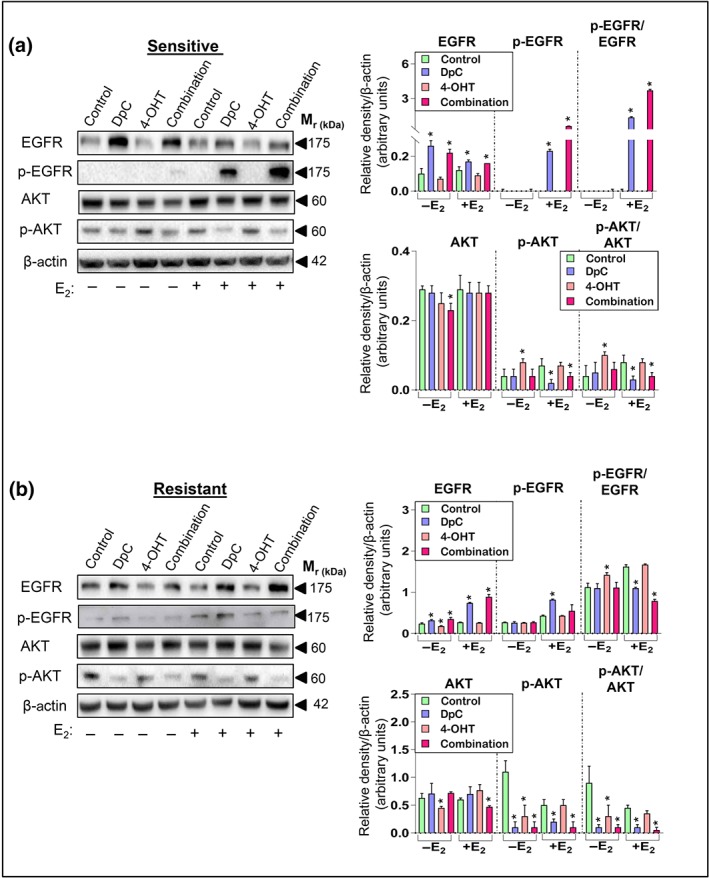

To determine whether the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT was due to inhibition of EGFR signalling, we assessed total EGFR and its activating phosphorylation at Tyr1068 in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells.

Considering its ability to down‐regulate EGFR in other cell types (Kovacevic et al., 2016), it was unexpected that DpC alone or in combination with 4‐OHT up‐regulated EGFR in sensitive and resistant cells, regardless of E2 treatment (Figure 3a,b). Further, DpC and the combination of DpC with 4‐OHT also distinctly up‐regulated p‐EGFR, although this was only evident in the presence of E2 in sensitive cells (Figure 3a). In resistant cells, DpC also significantly increased p‐EGFR when E2 was present (Figure 3b), although this effect was far less pronounced than in sensitive cells (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

DpC inhibits downstream AKT activation in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells. Western blot analysis of total EGFR and its phosphorylation at Tyr1068, along with total AKT and its phosphorylation at Ser473 in (a) tamoxifen‐sensitive and (b) tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells treated with either control media or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein loading control. Data represent the mean ± SD of five independent experiments. *P < .05, significantly different from the respective control

Conversely, 4‐OHT had no significant effect on total or phosphorylated EGFR in the sensitive cells (Figure 3a), while a slight but significant reduction in total EGFR was observed in resistant cells in the absence of E2 (Figure 3b). The ratio of p‐EGFR/EGFR was significantly increased for DpC and the combination in sensitive cells in the presence of E2 (Figure 3a), while a significant decrease in this ratio was observed under these conditions in resistant cells (Figure 3b). Overall, these results suggest that DpC promotes EGFR phosphorylation in sensitive MCF‐7 cells to a much greater extent than in resistant cells.

To further investigate this, we examined these cells in the presence of E2 and EGF together, as addition of EGF results in more robust EGFR activation (Stabile et al., 2005). Under control conditions, endogenous EGFR was very low in sensitive cells, with E2 + EGF having no substantial effect on EGFR (Figure S2A). In response to DpC alone, total and p‐EGFR levels were markedly increased in sensitive cells (Figure S2A), as observed with E2 alone (Figure 3a). However, the stimulatory effect of EGF + E2 on p‐EGFR was inhibited when DpC was combined with 4‐OHT (Figure S2A).

The resistant cells had much higher endogenous EGFR and to a lesser extent, p‐EGFR, than sensitive cells (Figure S2A). Further, resistant cells responded strongly to E2 + EGF treatment, with a pronounced increase in p‐EGFR observed after control, DpC, and 4‐OHT treatment, compared with the control without E2 + EGF (Figure S2A). However, this increase of p‐EGFR in resistant cells incubated with E2 and EGF was not observed with the combination treatment (Figure S2A). Hence, in the presence of E2 + EGF, the DpC and 4‐OHT combination potently inhibited EGFR activation.

To determine whether other major receptors were affected by these chemotherapeutic agents, we also assessed HER2 and insulin‐like growth factor 1 receptor (https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=1801) in sensitive and resistant cells, as these receptors contribute to tamoxifen resistance (Osborne et al., 2003; Osborne et al., 2005; Riggins et al., 2007). While HER2 was not markedly affected by DpC or 4‐OHT in sensitive cells, this receptor was reduced by DpC and the combination in resistant cells, regardless of E2 (Figure S2B). Further, the combination of DpC with 4‐OHT decreased IGF1R levels in sensitive cells, while having no distinct effect in resistant cells (Figure S2B).

As EGFR, HER2, and IGF1R signalling pathways converge on similar downstream targets, we investigated their major target, AKT, and its activating phosphorylation at Ser473 (Levin & Pietras, 2008), in sensitive and resistant MCF‐7 cells (Figure 3a,b). Once activated via phosphorylation, AKT directly phosphorylates ER‐α at Ser167, which is a major contributor to tamoxifen resistance (Campbell et al., 2001). In sensitive cells, total AKT was significantly reduced by the combination in the absence of E2, while no distinct effect was observed under other conditions (Figure 3a). Interestingly, 4‐OHT markedly increased p‐AKT in the absence of E2, while p‐AKT was significantly reduced by DpC alone or the combination in the presence of E2 (Figure 3a). A similar effect was observed in resistant cells, with DpC and the combination also significantly decreasing p‐AKT under all conditions (Figure 3b).

Taken together, our results showed that AKT activation was substantially inhibited in resistant cells, suggesting a mechanism by which DpC and its combination with 4‐OHT overcome resistance.

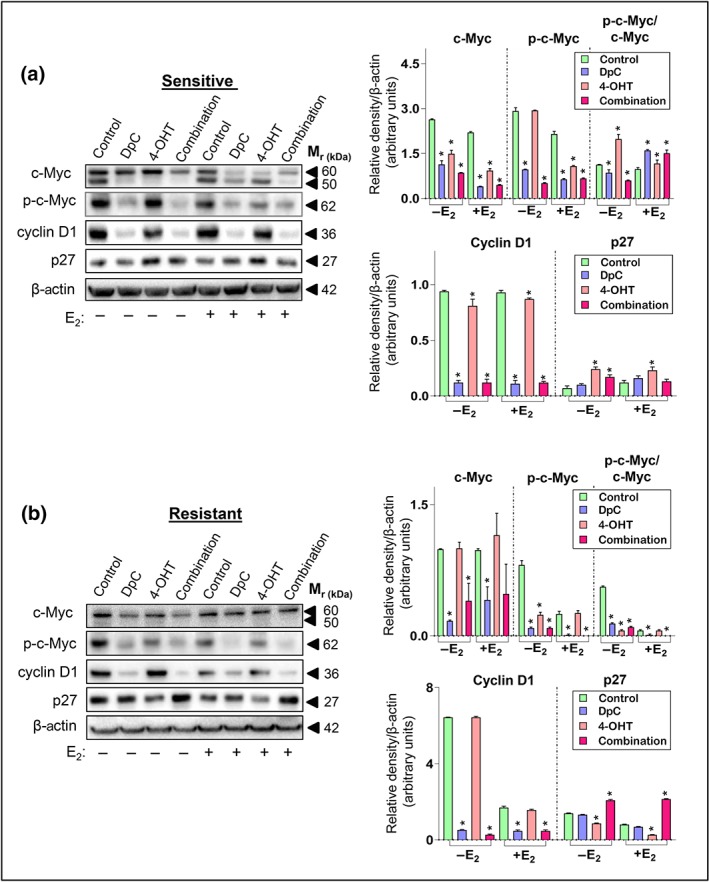

3.6. DpC combined with 4‐OHT attenuates c‐Myc and cyclin D1, while promoting p27 expression

We next assessed the major downstream targets of ER‐α and AKT, including c‐Myc and cyclin D1, both of which play oncogenic roles in breast cancer and are associated with tamoxifen resistance (Butt et al., 2005; Green et al., 2016; Sears, 2004). We also examined the tumour suppressor, p27, a major cyclin D1 inhibitor that attenuates proliferation (Chiarle, Pagano, & Inghirami, 2001).

In sensitive cells, c‐Myc was significantly down‐regulated under all conditions, with the combination having the most potent effect (Figure 4a). In these cells, c‐Myc was detected as two bands (~50 and 60 kDa), which may reflect different isoforms (Benassayag et al., 2005), or post‐translational modification (Hann, 2006), with quantitation assessing both bands as a total. Next, we examined phosphorylated c‐Myc (Ser62), as this phosphorylation is associated with increased c‐Myc stability and oncogenic activity (Sears, 2004; Yeh et al., 2004). Both DpC and the combination significantly decreased p‐c‐Myc under all conditions (Figure 4a). 4‐OHT also potently reduced p‐c‐Myc, but only in the presence of E2 in sensitive cells. A similar trend was observed for cyclin D1, with DpC and the combination significantly decreasing cyclin D1 under all conditions (Figure 4a). p27 was significantly increased by 4‐OHT in sensitive cells, while DpC had no significant effect (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Combining DpC with 4‐OHT inhibits c‐Myc and cyclin D1, while promoting p27 expression. Western blot analysis of c‐Myc and its phosphorylation site at Ser62, along with cyclin D1 and p27 in (a) sensitive‐ and (b) tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells treated with either control media or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein loading control. Data represent the mean ± SD of five independent experiments. *P < .05, significantly different from the respective control

In resistant cells, c‐Myc was predominantly expressed as the upper band (Figure 4b). DpC alone again significantly reduced total c‐Myc, p‐c‐Myc, and cyclin D1, while having no effect on p27 (Figure 4b). However, in direct contrast to its effects in sensitive cells (Figure 4a), 4‐OHT failed to decrease total c‐Myc or cyclin D1, while significantly reducing p27 in resistant cells (Figure 4b). This is in agreement with these cells being tamoxifen resistant (Kilker & Planas‐Silva, 2006). The combination was most effective in resistant cells, significantly decreasing c‐Myc phosphorylation and cyclin D1 expression and significantly increasing the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor, p27 (Figure 4b).

While the above studies were conducted with DpC at 5 μM, lower doses of DpC (i.e., 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM) alone or combined with 5‐μM 4‐OHT induced similar, dose‐dependent effects on ER‐α, p‐ER‐α, p‐AKT, p‐c‐Myc, and cyclin D1 in both sensitive and resistant cells (Figure S3).

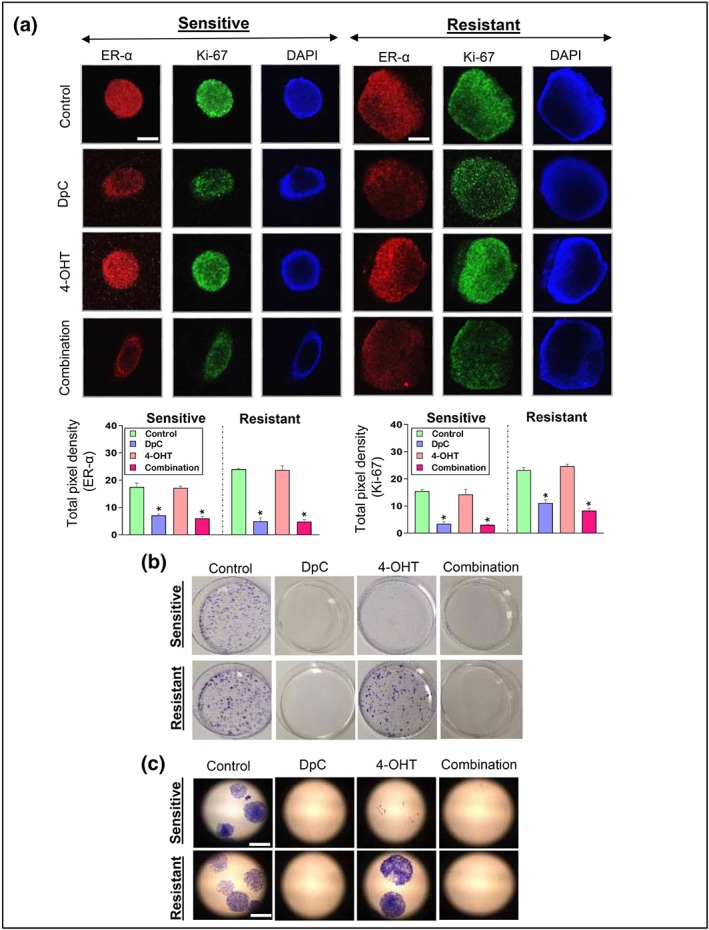

3.7. Combining DpC with 4‐OHT decreases proliferation and inhibits colony formation

To further assess the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT using more pathologically relevant tumour models, we examined these agents using 3D cell culture, where MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells were grown as spheroids. Spheroids better represent the in vivo setting and are more resistant to chemotherapy (Edmondson, Broglie, Adcock, & Yang, 2014; Nyga, Cheema, & Loizidou, 2011). Once established, spheroids were treated with DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination for 24 hr and examined for ER‐α and Ki‐67 (marker of proliferation; Yerushalmi, Woods, Ravdin, Hayes, & Gelmon, 2010) via immunofluorescence.

A significant down‐regulation of ER‐α and Ki‐67 was observed in sensitive and resistant spheroids treated with DpC alone or in combination with 4‐OHT (Figure 5a). Notably, 4‐OHT alone did not affect ER‐α and Ki‐67 under these conditions. These results support our current findings that down‐regulation of c‐Myc and cyclin D1 by DpC and the combination decreases proliferation. We also performed colony formation assays to determine the ability of sensitive and resistant cells to undergo unlimited division. While control cells formed large colonies, no colony formation was observed with DpC or the combination (Figure 5b,c). Further, 4‐OHT reduced colony formation in sensitive cells, but not in resistant cells where colonies were similar to the control (Figure 5b,c), which further confirms that these cells are resistant to tamoxifen.

Figure 5.

DpC and 4‐OHT inhibit 3D growth and colony formation of tamoxifen‐resistant and ‐sensitive MCF‐7 cells. (a) Representative images of ER‐α (red), Ki‐67 (green), and DAPI (blue) staining in multicellular 3D tumour spheroids of MCF‐7‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells treated with either control, DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) for 24 hr. The scale bar in the bottom right‐hand corner of the first image in each set represents 2 μm and is the same across all images. Quantification of pixel intensity for ER‐α and Ki‐67 was performed using ImageJ software and expressed as mean ± SD (five experiments). *P < .05, significantly different from the respective control. (b) Colony formation was analysed in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells in the presence of control media or media containing DpC (0.125 μM), 4‐OHT (0.125 μM), or their combination (0.125 μM each) for 21 days. Higher magnification (10×) images are shown in (c). Scale bar in the bottom right‐hand corner of the first image in (c) represents 2 μm and is the same across all images. Data represent five independent experiments

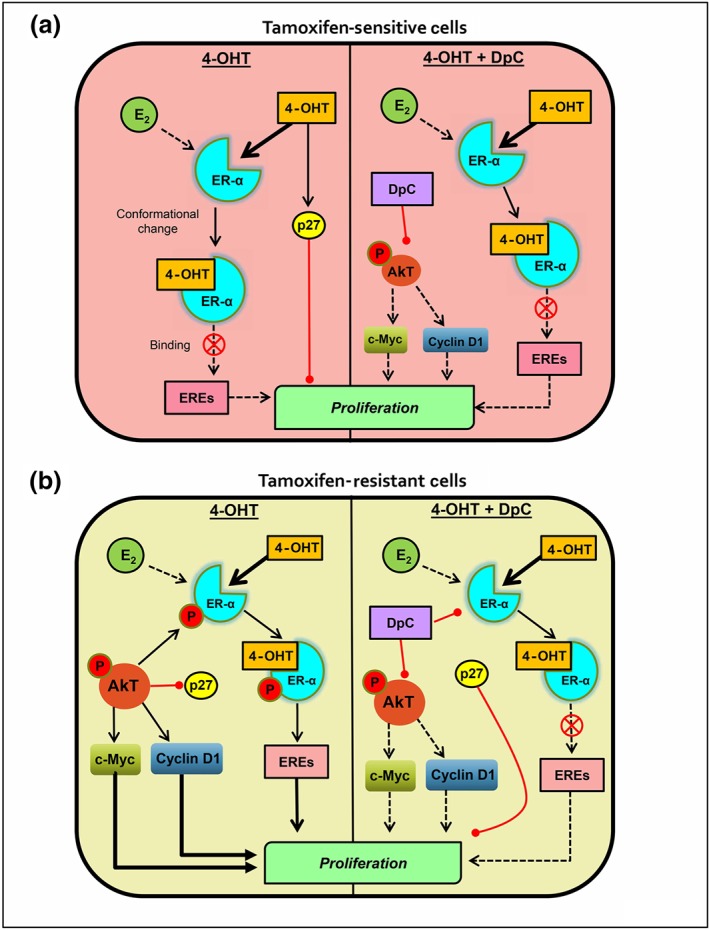

4. DISCUSSION

Various pathways contribute to tamoxifen resistance, with ER‐α over‐expression and its crosstalk with multiple oncogenic pathways such as EGFR and its downstream targets (i.e., AKT, c‐Myc, and cyclin D1) being major players (Butt et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2001; Chang, 2012; Fan et al., 2007; Ghayad et al., 2010; Knowlden et al., 2003). We demonstrated that the novel, clinically tested anti‐cancer agent, DpC, inhibits multiple oncogenic pathways, including EGFR, AKT, c‐Myc, and cyclin D1, in pancreatic and prostate cancer cells (Kovacevic et al., 2011; Kovacevic et al., 2016; Xi et al., 2017), leading to potent anti‐tumour activity in vitro and in vivo (Kovacevic et al., 2011; Lovejoy et al., 2012). These studies prompted us to examine the efficacy of DpC against breast cancer and its potential to overcome tamoxifen resistance.

Here, we have demonstrated that DpC has potent anti‐proliferative activity against ER‐positive, HER2 over‐expressing, and triple‐negative breast cancer cells. DpC was least effective against MDA‐MB‐231 triple‐negative cells, and this may be due to the absence of both ER‐α and HER2 (Holliday & Speirs, 2011), which we demonstrate are major DpC targets. DpC was most effective against ER‐positive cells, potently inhibiting proliferation and colony formation for tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells. Further, Chou–Talalay analysis demonstrated that the combination of DpC and 4‐OHT was synergistic in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells.

To elucidate the mechanisms of synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT, major molecular effectors in the development of tamoxifen resistance were examined. ER‐α was potently decreased by DpC in sensitive and resistant MCF‐7 cells using 2D and 3D culture. Further, the combination of DpC with 4‐OHT also decreased ER‐α and inhibited its transcriptional activity. These agents also decreased two major ER‐α co‐activators, namely, SRC3 and NF‐κB‐p65, further contributing to the reduced ER‐α transcriptional activity. In fact, NF‐κB‐p65 and SRC3 both contribute to tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer, and their inhibition may be a vital aspect of the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT in resistant cells (Biswas, Singh, Shi, Pardee, & Iglehart, 2005; Osborne et al., 2003).

The effect of DpC on reducing cyclin D1 and c‐Myc may further contribute to the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT, as cyclin D1 and c‐Myc are necessary for growth of tamoxifen‐resistant cells (Butt et al., 2005; Kilker et al., 2004; Kilker et al., 2006). Notably, cyclin D1 and c‐Myc are up‐regulated by p‐AKT, a major effector in the PI3K/AKT pathway (Butt et al., 2005; Kilker et al., 2006). We found that DpC alone, or in combination with 4‐OHT, strongly inhibited AKT activation in sensitive and resistant MCF‐7 cells. In fact, this inhibitory effect on AKT may be responsible for the decreased cyclin D1 and c‐Myc observed and could be central to the synergism between these two agents (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6.

Diagram of the effects of 4‐OHT alone or in combination with DpC in MCF‐7 tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells. (b) In the sensitive cells, E2 and 4‐OHT compete to bind to the ER‐α ligand binding site. Binding of 4‐OHT results in conformational change of the receptor, inhibiting its ability to promote the transcription of genes containing oestrogen response elements (EREs). 4‐OHT also up‐regulates p27, which further inhibits the cell cycle. When combined with 4‐OHT, DpC inhibits p‐AKT, leading to decreased c‐Myc and cyclin D1 levels, which further decrease tumour cell proliferation. (b) In tamoxifen‐resistant cells, increased activation of non‐genomic pathways enables enhanced AKT activation, which leads to (a) phosphorylation of the ER‐α receptor at Ser167, which enables its transcriptional activity, despite 4‐OHT binding (Likhite et al., 2006); (b) activation of downstream c‐Myc and cyclin D1; and (c) inhibition of p27 levels and activity (Kilker et al., 2006; Motti et al., 2004). Together, these effects drive proliferation and form the major mechanisms of resistance to 4‐OHT. Combining DpC with 4‐OHT in these cells inhibits p‐AKT, leading to reduced phosphorylation of ER‐α receptor at Ser167, as well as decreasing c‐Myc and cyclin D1 levels, consequently reducing tumour cell proliferation. By inhibiting p‐AKT, DpC also enables increased expression of p27 to further inhibit cell cycle progression

p‐AKT also promotes ER‐α activation by Ser167 phosphorylation, increasing ER‐α binding to DNA and promoting its transcriptional activity (Campbell et al., 2001; Likhite, Stossi, Kim, Katzenellenbogen, & Katzenellenbogen, 2006). However, it is important to note that while high levels of p‐ER‐α (Ser167) can correlate to good patient outcomes (Motomura et al., 2010), AKT is associated with poor outcomes and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer (Campbell et al., 2001). Here, DpC alone, or its combination with 4‐OHT, markedly decreased p‐ER‐α (Ser167) in resistant MCF‐7 cells. This may contribute to the synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT, as the resistant cells can no longer activate ER‐α via an intrinsic AKT‐mediated mechanism, leaving them more vulnerable to 4‐OHT. Alternatively, the ability of DpC to inhibit other major AKT targets (i.e., cyclin D1 and c‐Myc) and ER‐α co‐activators (i.e., SRC3 and NF‐κB‐p65) may be responsible for overcoming resistance to 4‐OHT.

Another protein that mediates breast cancer endocrine resistance is the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p27, with low levels being associated with breast cancer relapse (Arteaga, 2004). Restoration of p27 in endocrine‐resistant breast cancer cells re‐sensitizes them to anti‐oestrogen therapies (Arteaga, 2004). We showed that, in sensitive cells, 4‐OHT up‐regulated p27, which is in accordance with its anti‐proliferative activity (Kilker et al., 2006; Figure 6a). However, in resistant cells, p27 was decreased by 4‐OHT, demonstrating significant molecular alterations that confer tamoxifen resistance. While DpC alone did not affect p27, its combination with 4‐OHT induced a significant increase in p27 in resistant cells. This synergy may be mediated by the ability of DpC to decrease p‐AKT levels, as p‐AKT promotes degradation of p27 (Kilker et al., 2006; Motti, De Marco, Califano, Fusco, & Viglietto, 2004).

The expression and activation of EGFR is another key difference between tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant cells, with this protein being a major driver of tamoxifen resistance (Knowlden et al., 2003). In agreement with this, we demonstrate that the resistant cells had higher endogenous EGFR levels and responded robustly to E2 + EGF treatment by increasing activating phosphorylation of EGFR, which was in contrast to the sensitive cells. While DpC or its combination with 4‐OHT increased EGFR expression and activation in the sensitive cells, the activation of EGFR was reduced by DpC, and in particular its combination with 4‐OHT, in the resistant cells in the presence of E2 + EGF.

Importantly, downstream targets of EGFR signalling, namely, AKT, c‐Myc, and cyclin D1, were all decreased by DpC and its combination with 4‐OHT in both sensitive and resistant cells. This suggests that increased EGFR levels/activation observed under some conditions may be a compensatory response to counteract the inhibition of downstream signalling by DpC. Further, the inhibitory effect of these agents on downstream AKT signalling may also be mediated by other receptors, such as IGF1R and HER2, which were decreased by DpC alone and in combination with 4‐OHT in sensitive and resistant cells, respectively.

Another recently identified mechanism of anti‐oestrogen resistance involves the tumour micro‐environment (TME), with https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=4924 being produced by the TME and acting on breast cancer cells to promote resistance (Shee et al., 2018). FGF2 mediates its effects via the activation of MEK/ERK signalling to promote cyclin D1, which is vital for FGF2‐mediated resistance (Shee et al., 2018). Notably, we demonstrate here that DpC and particularly its combination with 4‐OHT potently inhibited cyclin D1 expression. Hence, this therapeutic approach may potentially also inhibit TME‐mediated mechanisms of resistance. However, further studies utilizing humanized in vivo models that incorporate the TME are required to assess this.

Overall, combining DpC with 4‐OHT was more effective than DpC alone against tamoxifen‐resistant cells, as shown by (a) the Chou–Talalay method demonstrating strong synergy between DpC and 4‐OHT (Figure 1c,f); (b) the combination treatment being most effective at inhibiting ER‐α transcriptional activity in resistant cells (Figure 2c); (c) the combination treatment most potently reducing ER‐α co‐activators SRC3 and NF‐κB‐p65 in resistant cells (Figure S1); and (d) only the combination treatment up‐regulated the tumour suppressor, p27, in resistant cells (Figure 4b). These results indicate that combining DpC with tamoxifen may be a promising therapeutic approach for ER‐positive breast cancer to overcome endocrine resistance.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.N.M. designed and performed experiments, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. S.C.L. performed experiments and analysed data. R.H. analysed data. Z.K., P.J.J., and D.R.R. designed experiments, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

DECLARATION OF TRANSPARENCY AND SCIENTIFIC RIGOUR

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research as stated in the BJP guidelines for https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bph.14207, and https://bpspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bph.14208, and as recommended by funding agencies, publishers, and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Supporting information

Table S1. Combination Index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) values for DpC and 4‐OHT at different IC50 iterations (i.e. 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 or 8 x IC50) in MCF‐7 Sensitive Cells.

Table S2. Combination Index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) values for DpC and 4‐OHT at different IC50 iterations (i.e. 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 or 8 x IC50) in MCF‐7 Resistant Cells.

Figure S1. Western blot analysis of SRC3, NF‐κB‐p65 and p‐NF‐κB‐p65 (Ser 536) in MCF‐7 sensitive (A) and resistant (B) cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.

Figure S2. (A) Western blot analysis of EGFR and p‐EGFR in MCF‐7 sensitive and resistant cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2 + EGF. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of total HER and IGF1R levels in sensitive and Tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC, 4‐OHT or their combination in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.

Figure S3. Western blot analysis of ER‐α, p‐ER‐α, p‐AKT, p‐c‐Myc and cyclin D1 in MCF‐7 sensitive (A) and resistant (B) cells treated with either control, DpC (0.1, 0.5 or 1 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM) or the combination of 4‐OHT (5 μM) with DpC (0.1, 0.5 or 1 μM) in the presence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by (a) Priority‐driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme (PdCCRS) Young Investigator Grant (1086449) awarded to Z.K., which was co‐funded by Cure Cancer Australia Foundation and Cancer Australia, and (b) PdCCRS Project Grant (1146599) awarded to D.R.R. and Z.K. and co‐funded by the National Breast Cancer Foundation and Cancer Australia. Z.K. is grateful for a University of Sydney Bridging Fellowship, a National Health and Medical Research Council RD Wright Fellowship (APP1140447), and a Cancer Institute New South Wales (CINSW) Career Development Fellowship (CDF171126). D.R.R. appreciates an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1062607 and 1159596). P.J.J. was supported by a CINSW Career Development Fellowship (CDF141147). S.N.M acknowledges funding provided by IRSIP‐HEC (Pakistan) and the Molecular Pathology and Pharmacology Program (USYD). We would also like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Caldon (Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney) for providing the tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant MCF‐7 cells and valuable experimental advice.

Maqbool SN, Lim SC, Park KC, et al. Overcoming tamoxifen resistance in oestrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer using the novel thiosemicarbazone anti‐cancer agent, DpC. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:2365–2380. 10.1111/bph.14985

Contributor Information

Des R. Richardson, Email: d.richardson@med.usyd.edu.au.

Patric J. Jansson, Email: patric.jansson@sydney.edu.au.

Zaklina Kovacevic, Email: zaklina.kovacevic@sydney.edu.au.

REFERENCES

- Acconcia, F. , & Kumar, R. (2006). Signaling regulation of genomic and nongenomic functions of estrogen receptors. Cancer Letters, 238, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Cidlowski, J. A. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , … CGTP Collaborators (2019). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Nuclear hormone receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S229–S246. 10.1111/bph.14750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , … CGTP Collaborators (2019a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Catalytic receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S247–S296. 10.1111/bph.14751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , … CGTP Collaborators (2019b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S297–S396. 10.1111/bph.14752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S. , Rasool, M. , Chaoudhry, H. , Pushparaj, P. N. , Jha, P. , Hafiz, A. , … Ali, A. (2016). Molecular mechanisms and mode of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Bioinformation, 12, 135–139. 10.6026/97320630012135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga, C. L. (2004). Cdk inhibitor p27Kip1 and hormone dependence in breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 10, 368S–371S. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-031204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benassayag, C. , Montero, L. , Colombie, N. , Gallant, P. , Cribbs, D. , & Morello, D. (2005). Human c‐Myc isoforms differentially regulate cell growth and apoptosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 25, 9897–9909. 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9897-9909.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, D. K. , Singh, S. , Shi, Q. , Pardee, A. B. , & Iglehart, J. D. (2005). Crossroads of estrogen receptor and NF‐κB signaling. Science STKE 2005: pe, 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostner, J. , Karlsson, E. , Pandiyan, M. J. , Westman, H. , Skoog, L. , Fornander, T. , … Stål, O. (2013). Activation of Akt, mTOR, and the estrogen receptor as a signature to predict tamoxifen treatment benefit. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 137, 397–406. 10.1007/s10549-012-2376-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A. J. , McNeil, C. M. , Musgrove, E. A. , & Sutherland, R. L. (2005). Downstream targets of growth factor and oestrogen signalling and endocrine resistance: The potential roles of c‐Myc, cyclin D1 and cyclin E. Endocrine‐Related Cancer, 12(Suppl 1), S47–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R. A. , Bhat‐Nakshatri, P. , Patel, N. M. , Constantinidou, D. , Ali, S. , & Nakshatri, H. (2001). Phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase/AKT‐mediated activation of estrogen receptor α: A new model for anti‐estrogen resistance. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276, 9817–9824. 10.1074/jbc.M010840200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M. (2012). Tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Biomol Ther (Seoul), 20, 256–267. 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.3.256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. , Zhang, D. , Yue, F. , Zheng, M. , Kovacevic, Z. , & Richardson, D. R. (2012). The iron chelators Dp44mT and DFO inhibit TGF‐β‐induced epithelial‐mesenchymal transition via up‐regulation of N‐Myc downstream‐regulated gene 1 (NDRG1). The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287, 17016–17028. 10.1074/jbc.M112.350470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarle, R. , Pagano, M. , & Inghirami, G. (2001). The cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and its prognostic role in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research, 3, 91–94. 10.1186/bcr277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, T. C. (2006). Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacological Reviews, 58, 621–681. 10.1124/pr.58.3.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou, T. C. (2010). Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou‐Talalay method. Cancer Research, 70, 440–446. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M. J. , Alexander, S. , Cirino, G. , Docherty, J. R. , George, C. H. , Giembycz, M. A. , … Ahluwalia, A. (2018). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting II: Updated and simplified guidance for authors and peer reviewers. British Journal of Pharmacology, 175, 987–993. 10.1111/bph.14153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, R. , Broglie, J. J. , Adcock, A. F. , & Yang, L. (2014). Three‐dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell‐based biosensors. Assay and Drug Development Technologies, 12, 207–218. 10.1089/adt.2014.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, P. , Wang, J. , Santen, R. J. , & Yue, W. (2007). Long‐term treatment with tamoxifen facilitates translocation of estrogen receptor alpha out of the nucleus and enhances its interaction with EGFR in MCF‐7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Research, 67, 1352–1360. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J. , & Richardson, D. R. (2001). The potential of iron chelators of the pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone class as effective antiproliferative agents, IV: The mechanisms involved in inhibiting cell‐cycle progression. Blood, 98, 842–850. 10.1182/blood.v98.3.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayad, S. E. , Vendrell, J. A. , Ben Larbi, S. , Dumontet, C. , Bieche, I. , & Cohen, P. A. (2010). Endocrine resistance associated with activated ErbB system in breast cancer cells is reversed by inhibiting MAPK or PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. International Journal of Cancer, 126, 545–562. 10.1002/ijc.24750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gionet, N. , Jansson, D. , Mader, S. , & Pratt, M. A. (2009). NF‐κB and estrogen receptor α interactions: Differential function in estrogen receptor‐negative and ‐positive hormone‐independent breast cancer cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 107, 448–459. 10.1002/jcb.22141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, A. R. , Aleskandarany, M. A. , Agarwal, D. , Elsheikh, S. , Nolan, C. C. , Diez‐Rodriguez, M. , … Rakha, E. A. (2016). MYC functions are specific in biological subtypes of breast cancer and confers resistance to endocrine therapy in luminal tumours. British Journal of Cancer, 114, 917–928. 10.1038/bjc.2016.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z. L. , Richardson, D. R. , Kalinowski, D. S. , Kovacevic, Z. , Tan‐Un, K. C. , & Chan, G. C. (2016). The novel thiosemicarbazone, di‐2‐pyridylketone 4‐cyclohexyl‐4‐methyl‐3‐thiosemicarbazone (DpC), inhibits neuroblastoma growth in vitro and in vivo via multiple mechanisms. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 9, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hann, S. R. (2006). Role of post‐translational modifications in regulating c‐Myc proteolysis, transcriptional activity and biological function. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 16, 288–302. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. D. , Sharman, J. L. , Faccenda, E. , Southan, C. , Pawson, A. J. , Ireland, S. , … NC‐IUPHAR (2018). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: Updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Research, 46, D1091–D1106. 10.1093/nar/gkx1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, S. I. , Eguchi, H. , Tanimoto, K. , Yoshida, T. , Omoto, Y. , Inoue, A. , … Yamaguchi, Y. (2003). The expression and function of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in human breast cancer and its clinical application. Endocrine‐Related Cancer, 10, 193–202. 10.1677/erc.0.0100193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, D. L. , & Speirs, V. (2011). Choosing the right cell line for breast cancer research. Breast Cancer Research, 13, 215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiyesimi, I. A. , Buzdar, A. U. , Decker, D. A. , & Hortobagyi, G. N. (1995). Use of tamoxifen for breast cancer: Twenty‐eight years later. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 13, 513–529. 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.2.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, P. J. , Kalinowski, D. S. , Lane, D. J. , Kovacevic, Z. , Seebacher, N. A. , Fouani, L. , … Richardson, D. R. (2015). The renaissance of polypharmacology in the development of anti‐cancer therapeutics: Inhibition of the “Triad of Death” in cancer by Di‐2‐pyridylketone thiosemicarbazones. Pharmacological Research, 100, 255–260. 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, S. , Endoh, H. , Masuhiro, Y. , Kitamoto, T. , Uchiyama, S. , Sasaki, H. , … Chambon, P. (1995). Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen‐activated protein kinase. Science, 270, 1491–1494. 10.1126/science.270.5241.1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilker, R. L. , Hartl, M. W. , Rutherford, T. M. , & Planas‐Silva, M. D. (2004). Cyclin D1 expression is dependent on estrogen receptor function in tamoxifen‐resistant breast cancer cells. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 92, 63–71. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilker, R. L. , & Planas‐Silva, M. D. (2006). Cyclin D1 is necessary for tamoxifen‐induced cell cycle progression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Research, 66, 11478–11484. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge, C. M. (2001). Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Research, 29, 2905–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowlden, J. M. , Hutcheson, I. R. , Jones, H. E. , Madden, T. , Gee, J. M. , Harper, M. E. , … Nicholson, R. I. (2003). Elevated levels of epidermal growth factor receptor/c‐erbB2 heterodimers mediate an autocrine growth regulatory pathway in tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells. Endocrinology, 144, 1032–1044. 10.1210/en.2002-220620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevic, Z. , Chikhani, S. , Lovejoy, D. B. , & Richardson, D. R. (2011). Novel thiosemicarbazone iron chelators induce up‐regulation and phosphorylation of the metastasis suppressor N‐myc down‐stream regulated gene 1: A new strategy for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Molecular Pharmacology, 80, 598–609. 10.1124/mol.111.073627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacevic, Z. , Menezes, S. V. , Sahni, S. , Kalinowski, D. S. , Bae, D. H. , Lane, D. J. , & Richardson, D. R. (2016). The metastasis suppressor, N‐MYC downstream‐regulated gene‐1 (NDRG1), down‐regulates the ErbB family of receptors to inhibit downstream oncogenic signaling pathways. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291, 1029–1052. 10.1074/jbc.M115.689653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane, D. J. , Saletta, F. , Suryo Rahmanto, Y. , Kovacevic, Z. , & Richardson, D. R. (2013). N‐myc downstream regulated 1 (NDRG1) is regulated by eukaryotic initiation factor 3a (eIF3a) during cellular stress caused by iron depletion. PLoS ONE, 8, e57273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. H. , Koh, D. , Na, H. , Ka, N. L. , Kim, S. , Kim, H. J. , … Lee, M. O. (2018). MTA1 is a novel regulator of autophagy that induces tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. Autophagy, 14, 812–824. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1388476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, E. R. , & Pietras, R. J. (2008). Estrogen receptors outside the nucleus in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 108, 351–361. 10.1007/s10549-007-9618-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhite, V. S. , Stossi, F. , Kim, K. , Katzenellenbogen, B. S. , & Katzenellenbogen, J. A. (2006). Kinase‐specific phosphorylation of the estrogen receptor changes receptor interactions with ligand, deoxyribonucleic acid, and coregulators associated with alterations in estrogen and tamoxifen activity. Molecular Endocrinology, 20, 3120–3132. 10.1210/me.2006-0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy, D. B. , Sharp, D. M. , Seebacher, N. , Obeidy, P. , Prichard, T. , Stefani, C. , … Richardson, D. R. (2012). Novel second‐generation di‐2‐pyridylketone thiosemicarbazones show synergism with standard chemotherapeutics and demonstrate potent activity against lung cancer xenografts after oral and intravenous administration in vivo. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 55, 7230–7244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui, G. Y. , Kovacevic, Z. , Richardson, V. , Merlot, A. M. , Kalinowski, D. S. , & Richardson, D. R. (2015). Targeting cancer by binding iron: Dissecting cellular signaling pathways. Oncotarget, 6, 18748–18779. 10.18632/oncotarget.4349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. A. , & Katzenellenbogen, B. S. (1983). Characterization and quantitation of antiestrogen binding sites in estrogen receptor‐positive and ‐negative human breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Research, 43, 3094–3100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motomura, K. , Ishitobi, M. , Komoike, Y. , Koyama, H. , Nagase, H. , Inaji, H. , & Noguchi, S. (2010). Expression of estrogen receptor beta and phosphorylation of estrogen receptor alpha serine 167 correlate with progression‐free survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer treated with aromatase inhibitors. Oncology, 79, 55–61. 10.1159/000319540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motti, M. L. , De Marco, C. , Califano, D. , Fusco, A. , & Viglietto, G. (2004). Akt‐dependent T198 phosphorylation of cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p27kip1 in breast cancer. Cell Cycle, 3, 1074–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyga, A. , Cheema, U. , & Loizidou, M. (2011). 3D tumour models: Novel in vitro approaches to cancer studies. J Cell Commun Signal, 5, 239–248. 10.1007/s12079-011-0132-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrero, M. , Yu, D. V. , & Shapiro, D. J. (2002). Estrogen receptor‐dependent and estrogen receptor‐independent pathways for tamoxifen and 4‐hydroxytamoxifen‐induced programmed cell death. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277, 45695–45703. 10.1074/jbc.M208092200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C. K. (1998). Tamoxifen in the treatment of breast cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 339, 1609–1618. 10.1056/NEJM199811263392207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C. K. , Bardou, V. , Hopp, T. A. , Chamness, G. C. , Hilsenbeck, S. G. , Fuqua, S. A. , … Schiff, R. (2003). Role of the estrogen receptor coactivator AIB1 (SRC‐3) and HER‐2/neu in tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 95, 353–361. 10.1093/jnci/95.5.353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C. K. , Shou, J. , Massarweh, S. , & Schiff, R. (2005). Crosstalk between estrogen receptor and growth factor receptor pathways as a cause for endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 11, 865s–870s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D. R. , Tran, E. H. , & Ponka, P. (1995). The potential of iron chelators of the pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone class as effective antiproliferative agents. Blood, 86, 4295–4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggins, R. B. , Schrecengost, R. S. , Guerrero, M. S. , & Bouton, A. H. (2007). Pathways to tamoxifen resistance. Cancer Letters, 256, 1–24. 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring, A. , & Dowsett, M. (2004). Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocrine‐Related Cancer, 11, 643–658. 10.1677/erc.1.00776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen, R. J. , Fan, P. , Zhang, Z. , Bao, Y. , Song, R. X. , & Yue, W. (2009). Estrogen signals via an extra‐nuclear pathway involving IGF‐1R and EGFR in tamoxifen‐sensitive and ‐resistant breast cancer cells. Steroids, 74, 586–594. 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears, R. C. (2004). The life cycle of C‐myc: From synthesis to degradation. Cell Cycle, 3, 1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestak, V. , Stariat, J. , Cermanova, J. , Potuckova, E. , Chladek, J. , Roh, J. , … Kovarikova, P. (2015). Novel and potent anti‐tumor and anti‐metastatic di‐2‐pyridylketone thiosemicarbazones demonstrate marked differences in pharmacology between the first and second generation lead agents. Oncotarget, 6, 42411–42428. 10.18632/oncotarget.6389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shee, K. , Yang, W. , Hinds, J. W. , Hampsch, R. A. , Varn, F. S. , Traphagen, N. A. , … Miller, T. W. (2018). Therapeutically targeting tumor microenvironment‐mediated drug resistance in estrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 215, 895–910. 10.1084/jem.20171818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabile, L. P. , Lyker, J. S. , Gubish, C. T. , Zhang, W. , Grandis, J. R. , & Siegfried, J. M. (2005). Combined targeting of the estrogen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor in non‐small cell lung cancer shows enhanced antiproliferative effects. Cancer Research, 65, 1459–1470. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M. , Paciga, J. E. , Feldman, R. I. , Yuan, Z. , Coppola, D. , Lu, Y. Y. , … Cheng, J. Q. (2001). Phosphatidylinositol‐3‐OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT2, activated in breast cancer, regulates and is induced by estrogen receptor α (ERα) via interaction between ERα and PI3K. Cancer Research, 61, 5985–5991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vranic, S. , Gatalica, Z. , & Wang, Z. Y. (2011). Update on the molecular profile of the MDA‐MB‐453 cell line as a model for apocrine breast carcinoma studies. Oncology Letters, 2, 1131–1137. 10.3892/ol.2011.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi, R. , Pun, I. H. , Menezes, S. V. , Fouani, L. , Kalinowski, D. S. , Huang, M. L. , … Kovacevic, Z. (2017). Novel thiosemicarbazones inhibit lysine‐rich carcinoembryonic antigen‐related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) coisolated (LYRIC) and the LYRIC‐induced epithelial‐mesenchymal transition via upregulation of N‐Myc downstream‐regulated gene 1 (NDRG1). Molecular Pharmacology, 91, 499–517. 10.1124/mol.116.107870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, E. , Cunningham, M. , Arnold, H. , Chasse, D. , Monteith, T. , Ivaldi, G. , … Sears, R. (2004). A signalling pathway controlling c‐Myc degradation that impacts oncogenic transformation of human cells. Nature Cell Biology, 6, 308–318. 10.1038/ncb1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yerushalmi, R. , Woods, R. , Ravdin, P. M. , Hayes, M. M. , & Gelmon, K. A. (2010). Ki67 in breast cancer: Prognostic and predictive potential. The Lancet Oncology, 11, 174–183. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70262-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. H. , Man, H. T. , Zhao, X. D. , Dong, N. , & Ma, S. L. (2014). Estrogen receptor‐positive breast cancer molecular signatures and therapeutic potentials (Review). Biomed Rep, 2, 41–52. 10.3892/br.2013.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Combination Index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) values for DpC and 4‐OHT at different IC50 iterations (i.e. 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 or 8 x IC50) in MCF‐7 Sensitive Cells.

Table S2. Combination Index (CI) and dose reduction index (DRI) values for DpC and 4‐OHT at different IC50 iterations (i.e. 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 or 8 x IC50) in MCF‐7 Resistant Cells.

Figure S1. Western blot analysis of SRC3, NF‐κB‐p65 and p‐NF‐κB‐p65 (Ser 536) in MCF‐7 sensitive (A) and resistant (B) cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.

Figure S2. (A) Western blot analysis of EGFR and p‐EGFR in MCF‐7 sensitive and resistant cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC (5 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM), or their combination (5 μM each) in the presence or absence of E2 + EGF. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of total HER and IGF1R levels in sensitive and Tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 cells treated with either control media, or media containing DpC, 4‐OHT or their combination in the presence or absence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.

Figure S3. Western blot analysis of ER‐α, p‐ER‐α, p‐AKT, p‐c‐Myc and cyclin D1 in MCF‐7 sensitive (A) and resistant (B) cells treated with either control, DpC (0.1, 0.5 or 1 μM), 4‐OHT (5 μM) or the combination of 4‐OHT (5 μM) with DpC (0.1, 0.5 or 1 μM) in the presence of E2. β‐actin was used as a protein‐loading control.