Abstract

Recent studies have examined the effects of conventional transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on working memory (WM) performance, but this method has relatively low spatial precision and generally involves a reference electrode that complicates interpretation. Herein, we report a repeated-measures crossover study of 25 healthy adults who underwent multielectrode tDCS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), right DLPFC, or sham in 3 separate visits. Shortly after each stimulation session, participants performed a verbal WM (VWM) task during magnetoencephalography, and the resulting data were examined in the time–frequency domain and imaged using a beamformer. We found that after left DLPFC stimulation, participants exhibited stronger responses across a network of left-lateralized cortical areas, including the supramarginal gyrus, prefrontal cortex, inferior frontal gyrus, and cuneus, as well as the right hemispheric homologues of these regions. Importantly, these effects were specific to the alpha-band, which has been previously implicated in VWM processing. Although stimulation condition did not significantly affect performance, stepwise regression revealed a relationship between reaction time and response amplitude in the left precuneus and supramarginal gyrus. These findings suggest that multielectrode tDCS targeting the left DLPFC affects the neural dynamics underlying offline VWM processing, including utilization of a more extensive bilateral cortical network.

Keywords: magnetoencephalography, neurostimulation, transcranial direct current stimulation, working memory

Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is an emerging noninvasive method to modulate cortical brain activity that involves applying a relatively small electrical current (i.e., < 2 milliamps) to the scalp surface. tDCS is not strong enough to induce action potentials in the brain (Filmer et al. 2014; Fertonani and Miniussi 2017) but is thought to alter the response threshold of underlying neurons by directly altering the local ionic environment (Nitsche and Paulus 2000, 2001; Liebetanz et al. 2002; Nitsche et al. 2003a, 2003b; Coffman et al. 2014) and by purported polarity-dependent effects on gamma-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamatergic activity (Liebetanz et al. 2002; Nitsche et al. 2005; Stagg et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2014; Bachtiar et al. 2015). Such changes are thought to extend well beyond the time period immediately following the stimulation session (Kuo et al. 2013; Bachtiar et al. 2015), which results in prolonged “offline” effects of tDCS on cognitive function (Manuel and Schnider 2016; Metzuyanim-Gorlick and Mashal 2016; Wiesman et al. 2018; McDermott et al. 2019).

One cognitive faculty that has repeatedly been the target of tDCS is working memory (WM) (Hill et al. 2016; Mancuso et al. 2016), which involves the real-time storage, retention, and retrieval of incoming stimulus information in order to complete everyday tasks. WM consists of 3 phases: encoding, which involves the process of transforming information from a physical representation to a physiological representation and entering it into a short-term buffer, maintenance, which involves storing the representations for a short amount of time for future processing, and retrieval, which involves retrieving the elements from memory storage and using them to complete a task (Baddeley, 1992). In terms of its neural bases, verbal WM (VWM) has been found to heavily involve left-lateralized frontal-parietal networks, superior temporal and occipital cortices, and the cerebellum (Cabeza and Nyberg 2000; D'Esposito 2007; Rottschy et al. 2012; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a, 2018b; Proskovec et al. 2018). These areas are also key in other higher level cognitive functions, including attention and verbal and visual processing. In terms of the spectro-temporal dynamics, alpha frequency (8–14 Hz) activity has been implicated as essential to VWM processing in these brain regions (Jensen et al. 2002; Jensen and Mazaheri 2010; Händel et al. 2011; Bonnefond and Jensen 2012; Roux and Uhlhaas 2014; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015,Proskovec et al. 2016). Most commonly, this alpha activity is observed in the form of a sustained left frontotemporal desynchronization throughout encoding and most of maintenance, and a strong synchronization in the occipital cortices during the maintenance phase, which is believed to reflect the inhibition of incoming visual information to help preserve visual memory representations.

Despite a large body of research into the potential therapeutic and clinical significance of tDCS in improving cognition, its impact on WM function in particular has remained elusive. Meta-analyses of the overall effect of tDCS (i.e., collapsed across different target regions) on WM have found that the purported improvement is negligible or even nonexistent (Mancuso et al. 2016; Brunoni et al. 2018), and some research has even reported negative effects on WM abilities (Marshall et al. 2005; Ferrucci et al. 2008). On the other hand, left prefrontal stimulation in particular has been found to modestly enhance WM performance in a meta-analysis (Mancuso et al. 2016). Concerning the underlying neuronal dynamics, tDCS-induced changes in neuronal excitability likely have the potential to both improve and hinder task performance by altering regional neural activity in facilitating or detrimental ways. Such disparate effects may arise due to differences in the stimulation montage and other parameters. For example, as mentioned above, most tDCS studies showing a WM-enhancing effect have used an anodal left prefrontal montage (Mancuso et al. 2016; Brunoni et al. 2018). Importantly, the vast majority of literature on this topic has used conventional tDCS, which requires 2 electrodes positioned at different locations (i.e., an anode and a cathode). While the so-called “reference” electrode (i.e., cathode) is often positioned on the right supraorbital region and assumed to have only a negligible effect on neural activity, this assumption has not been empirically demonstrated and may underlie some of the variability seen in the literature, especially in the area of WM. Multielectrode tDCS (ME-tDCS) circumvents this concern by using a “center-surround” configuration, where the center electrode is surrounded by a number of electrodes of the opposing polarity. Beyond minimizing the concern with a “reference,” ME-tDCS also creates a much more focal current loop near the brain area of interest (Datta et al. 2008; Datta et al. 2009; Edwards et al. 2013; Kuo et al. 2013). Very few studies have used ME-tDCS to investigate the effects of prefrontal stimulation on VWM function, and even fewer have probed the underlying neural dynamics. In sum, the effect of tDCS on VWM function remains a matter of debate, and the underlying alterations in neuronal dynamics are even further unknown.

In the current study, we investigate the offline behavioral and neural effects of prefrontal ME-tDCS on VWM function using the high temporal and spatial precision of magnetoencephalography (MEG). Briefly, healthy adults completed a 3-session, single-blind, cross-over design that included sham stimulation and 20 minutes of ME-tDCS to the left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortices (DLPFC). Combined with behavioral outcomes, we quantify how prefrontal stimulation with ME-tDCS affects the network level dynamics underlying VWM processing. Due to the established importance of the left DLPFC for VWM function, our primary hypothesis was that left prefrontal stimulation would uniquely impact the oscillatory neural dynamics serving VWM function across a network of cortical regions involved in verbal perception, processing, and comprehension. Further, we expected that these altered neural dynamics would be predictive of performance on the task, signaling their importance in VWM processing.

Materials and Methods

Participants

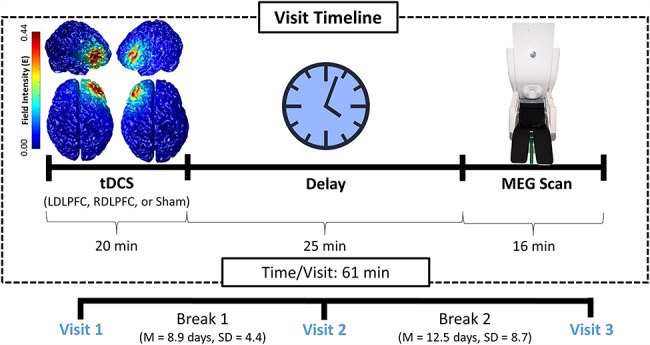

We collected data from 25 healthy adults for this study. All participants were between the ages of 19 and 32 years (10 females; mean age = 23.4; standard deviation (SD) = 3.56; 24 right-handed). Exclusionary criteria included any neurological or psychiatric disorder, any medical illness known to affect central nervous system function (e.g., stroke, neurodegenerative disorders, multiple sclerosis, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia, HIV infection, lupus, history of or current cancer, major heart conditions), history of head trauma, current substance abuse, and any nonremovable metal implants that would interfere with MEG data acquisition. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center reviewed and approved this investigation. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant following a detailed description of the study. Each participant completed 3 consecutive visits at least 1 week apart (mean delay: 10.75 days, SD: 7.14 days; Fig. 1) and received 1 of the 3 stimulation conditions on each visit (i.e., right DLPFC, left DLPFC, sham), followed by MEG recording. With the exception of the pseudorandomized order of the stimulation condition across the 3 visits, all participants completed the same experimental protocol on each visit.

Figure 1.

Visit timeline. In each of the 3 visits, participants underwent a ME-tDCS session targeting either the left DLPFC, right DLPFC, or a Sham session (pseudorandomized and single-blinded). About 25 minutes after tDCS, participants completed the VWM task during MEG. The remaining 2 stimulation sessions and accompanying MEG scans were completed at later dates at least 1 week apart.

tDCS Protocol

A within-subjects crossover design was implemented to elucidate the effects of tDCS on VWM performance. Participants were blinded to their condition at each visit (Fig. 1), as were all personnel involved in data management and the early stages of data processing (i.e., filtering, artifact rejection, sensor-level statistical comparisons, and beamforming). Each tDCS electrode was secured atop electroconductive gel using an electroencephalography (EEG) cap and positioned using the International 10/20 system. Across all 3 conditions, a 4 × 1 multielectrode anode-center cathode-surround montage was employed, centered on either the left or right DLPFC, defined as F3 and F4 using the International 10–20 coordinate system. Importantly, Okamoto et al. (Okamoto et al. 2004; Okamoto and Dan 2005) have developed a method for transforming the scalp-based International 10–20 coordinate system to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI)-based coordinates. Briefly, using data from a large sample of healthy adults, they developed a probabilistic distribution of the cortical projection points in MNI space that corresponds to input coordinates from the International 10–20 system. Based on their data, coordinates in the International 10–20 system (i.e., scalp-based) can be estimated in MNI space with an average SD of 8 mm, which is negligible given the size of our tDCS array. Thus, we computed the coordinates of the tDCS array in the International 10–20 system and then used the transformation methods provided by Okamoto et al. (Okamoto et al. 2004; Okamoto and Dan 2005) to obtain the MNI coordinates that corresponded to these scalp-based locations. These data indicated that the different array configurations were centered over the left and right DLPFC, as designed. In the sham condition, the electrode array was placed in the same location and pseudorandomized across participants whether it was over the left or right DLPFC.

Participants in each anodal stimulation condition underwent 20 min of 2.0 mA stimulation, plus a 30 s ramp-up period, while completing a battery of neuropsychological measures to stay cognitively engaged during stimulation. Three dimensional current density modeling of this stimulation was performed using finite-element modeling of current flow to further verify that the DLPFCs were being targeted effectively (Kempe et al. 2014; Ruffini et al. 2014), and this analysis was performed in the COMETS2 toolbox (Lee et al. 2017). During the sham condition, participants completed the same neuropsychological battery for 20 min, but no stimulation was applied outside of the ∼30 s ramp-up period. A Soterix Medical (New York, NY, USA) tDCS system with a 4 × 1 ME-tDCS adaptor was used for stimulation. Following the active/sham stimulation, participants were prepared for MEG recording and then seated with their head positioned within the MEG helmet. This protocol was in line with the findings of Kuo et al. (Kuo et al. 2013) who found that the level of cortical excitability peaks about 20 min after the cessation of tDCS and then slowly dissipates over the next 70–90 min. Consistent with these data, Bachtiar et al. (Bachtiar et al. 2015) reported that local GABA decreases following anodal tDCS peaked about 20 min after stimulation, and previous papers from our lab have shown lasting effects of tDCS on cognition and neurophysiology from 20 to 90 minutes post-stimulation (Heinrichs-Graham et al. 2017; McDermott et al. 2019; Wiesman et al. 2018; Wilson et al. 2018). Thus, we aligned our MEG recording session to coincide with this period of altered neuronal excitability. During the interim, participants were allowed to clean the electroconductive gel from their hair before being prepared for their MEG scan. The latter included removal of all ferromagnetic items, digitization of the fiducials and head surface, and positioning within the instrument. Importantly, the VWM task described below was the second of 4 cognitive paradigms that all participants performed during MEG, all of which were within the time period of maximum tDCS-related neural alterations (see above). The other 3 tasks that all participants performed were designed to study visual selective attention, visuospatial processing, and abstract reasoning.

Task Paradigm

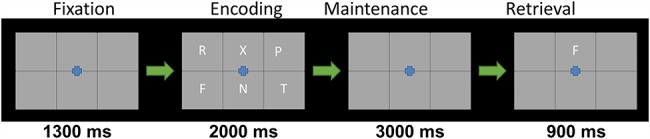

This study utilized an established paradigm to tap VWM function, which has been described in several previous studies from our laboratory (Fig. 2; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a). Briefly, participants were shown a centrally presented fixation embedded in a 3 × 2 grid for 1.3 s. An array of 6 consonants then appeared at fixed locations within the grid for 2.0 s (i.e., encoding). Following this, the letters disappeared, and the empty grid remained on the screen for 3.0 s (i.e., maintenance). A single probe letter then appeared in the grid for 0.9 s, and the participant was instructed to respond by button press with their right index or middle finger as to whether the probe was in or out of the previous array of letters (i.e., retrieval). A total of 128 trials were completed, equally split and pseudorandomized between in- and out-of-set trials, for a total run time of about 16 min.

Figure 2.

Sternberg VWM task. Each trial began with an empty 2 × 3 grid with a fixation cross in the center presented for 1300 ms, followed by a 2 × 3 grid of consonants presented for 2000 ms (encoding). Afterwards, the consonants disappeared for 3000 ms (maintenance). Finally, a 2 × 3 grid with a single probe consonant in the upper middle was presented for 900 ms (retrieval), and participants were tasked with responding (by button press) if the consonant was among the previous 6 letters (index finger) or not (middle finger).

MEG Acquisition and Coregistration

All recordings were conducted in a 1-layer magnetically shielded room with active shielding engaged. Neuromagnetic responses were sampled continuously at 1 kHz with an acquisition bandwidth of 0.1–330 Hz using an Elekta MEG system with 306 magnetic sensors (Elekta). Using MaxFilter (v2.2; Elekta), MEG data from each subject were individually corrected for head motion and subjected to noise reduction using the signal space separation method with a temporal extension (Taulu et al. 2005; Taulu and Simola 2006).

Prior to starting the MEG experiment, 4 coils were attached to the subject’s head and localized, together with the 3 fiducial points and scalp surface, with a 3-D digitizer (Fastrak 3SF0002, Polhemus Navigator Sciences). Once the subject was positioned for MEG recording, an electric current with a unique frequency label (e.g., 322 Hz) was fed to each of the coils. This induced a measurable magnetic field and allowed for each coil to be localized in reference to the sensors throughout the recording session. Since the coil locations were also known in head coordinates, all MEG measurements could be transformed into a common coordinate system. With this coordinate system, each participant’s MEG data were coregistered with a high-resolution structural T1-weighted template brain using Brain Electrical Source Analysis (BESA) MRI (Version 2.0). The structural MRI data were in standardized space and aligned parallel to the anterior and posterior commissures. Following source analysis (i.e., beamforming), each participant’s 4.0 × 4.0 × 4.0 mm MEG functional images were spatially resampled.

MEG Time Frequency Transformation and Statistics

Cardiac artifacts were removed from the data using signal-space projection, which was accounted for during source reconstruction (Uusitalo and Ilmoniemi 1997). The continuous magnetic time series was divided into epochs of 7.2 s duration, with the onset of the encoding grid defined as time 0.0 s and the baseline being defined as −0.2 to 0.0 s. Epochs containing artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle artifacts, etc.) were rejected based on individual amplitude and gradient thresholds, supplemented with visual inspection. Further, only trials where participants responded correctly were used in downstream analyses. This resulted in an average of 107.72 (SD = 9.81) correct and artifact-free trials in visit 1, 110.6 trials (SD = 13.56) in visit 2, and 110.6 trials (SD = 9.50) in visit 3, and there was no significant difference between the number of trials per visit (F [2, 72] = 0.560, P = 0.574). There was also no difference in the number of trials between stimulation conditions (F (2, 72) = 0.090, P = 0.914).

Artifact-free epochs were transformed into the time–frequency domain using complex demodulation, and the resulting spectral power estimations per sensor were averaged over trials to generate time–frequency plots of mean spectral density. These sensor-level data were normalized using the respective bin’s baseline power, which was calculated as the mean power during the −0.2 to 0.0 s time period. The specific time–frequency windows used for imaging were determined by statistical analysis of the sensor-level spectrograms across the entire array of gradiometers. To reduce the risk of false-positive results while maintaining reasonable sensitivity, a 2-stage procedure was followed to control for Type 1 error. In the first stage, 1-sample t-tests were conducted on each data point, and the output spectrogram of t-values was thresholded at P < 0.05 to define time–frequency bins containing potentially significant oscillatory deviations relative to baseline across all participants. In stage 2, time–frequency bins that survived the threshold were clustered with temporally and/or spectrally neighboring bins that were also above the (P < 0.05) threshold, and a cluster value was derived by summing all of the t-values of all data points in the cluster. Nonparametric permutation testing was then used to derive a distribution of cluster values, and the significance level of the observed clusters (from stage 1) was tested directly using this distribution (Ernst 2004; Maris and Oostenveld 2007). For each comparison, at least 1000 permutations were computed to build a distribution of cluster values. Based on these analyses, the time–frequency windows that contained significant oscillatory events across all participants were subjected to the beamforming analysis.

MEG Source Imaging and Statistics

Cortical networks were imaged using the dynamic imaging of coherent sources beamformer ( Van Veen et al. 1997; Gross et al. 2001), which employs spatial filters in the frequency domain to calculate source power for the entire brain volume. The single images were derived from the cross-spectral densities of all combinations of MEG gradiometers averaged over the time–frequency range of interest and the solution of the forward problem for each location on a grid specified by input voxel space. Following convention, we computed noise-normalized, source power per voxel in each participant using active (i.e., task) and passive (i.e., baseline) periods of equal duration and bandwidth (Van Veen et al. 1997; Hillebrand et al. 2005). Such images are typically referred to as pseudo-t maps, with units (pseudo-t) that reflect noise-normalized power differences (i.e., active vs. passive) per voxel. MEG preprocessing and imaging used the BESA version 6.1 software.

Normalized differential source power was computed for the statistically selected time-frequency bands (see below) over the entire brain volume per participant at 4.0 mm isotropic resolution. The resulting 3D maps of brain activity were averaged across all alpha encoding (8–14 Hz) time bins (300–1900 ms) and all alpha maintenance (12–18 Hz) time bins (2500–3300 ms). To assess the neuroanatomical basis of significant variations in these oscillatory neural responses as a function of tDCS condition, these maps were subjected to whole-brain repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVAs), with stimulation condition as the within-subjects factor. Multiple comparisons were accounted for in these ANOVAs by setting a stringent voxel-wise significance threshold of P < 0.01, paired with a cluster-wise voxel threshold of k > 200. This relatively conservative threshold was implemented to prevent the interpretation of false positives in the functional maps. For illustration purposes, the participant-level average maps were also averaged across participants within each condition to visualize differential patterns of cortical activity between stimulation conditions. Finally, to identify relationships between neural oscillatory activity and behavior, we extracted pseudo-t values from the peak voxel of each significant cluster within each time–frequency response (i.e., the alpha encoding and alpha maintenance responses) and entered them into stepwise multiple regression models for our behavioral performance metrics. This included 4 total models, one each for alpha encoding responses and alpha maintenance responses predicting reaction time (RT) and accuracy. Whole-brain statistics was performed in SPM12, and all other statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (V25).

Results

Current Distribution Modeling and Behavioral Effects

Over the course of 3 visits, participants underwent 3 different stimulation conditions with ME-tDCS: anodal right DLPFC, anodal left DLPFC, and sham left/right DLPFC. Three-dimensional current distribution modeling showed that the field intensity was strongest in the right and left DLPFCs for the 2 anodal stimulation conditions (Fig. 1). After stimulation, participants completed a VWM task during MEG. Participants performed well on the VWM task, both in terms of RT (left DLPFC = 742.26 ms, SD = 134.41 ms; right DLPFC = 738.42 ms, SD = 163.98 ms; sham = 740.42 ms, SD = 124.51 ms) and accuracy (left DLPFC = 86.06%, SD = 6.96%; right DLPFC = 85.06%, SD = 10.78%; sham = 85.84%, SD = 8.02%), but interestingly, there were no significant differences for accuracy nor RT between stimulation conditions (RT: F (2, 72) = 0.005, P = 0.995; Accuracy: F (2, 72) = 0.090, P = 0.914).

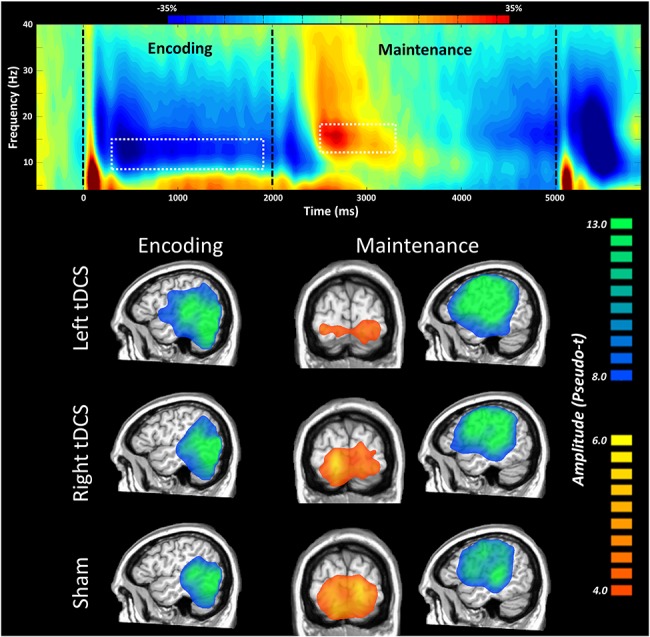

Alpha-frequency Responses to the VWM Task

Statistical analysis of the sensor-level spectrograms revealed significant oscillatory responses in the alpha band during both encoding (8–14 Hz; 300–1900 ms) and maintenance (12–18 Hz; 2500–3300 ms; Fig. 3 (top)). Beamformer source imaging revealed that these responses corresponded to a robust left-lateralized desynchronization throughout the occipital, parietal, temporal, and frontal cortices during the encoding phase, along with a robust desynchronization in the frontal cortices and a synchronization in the occipital cortices during the maintenance phase (Fig. 3, bottom). Qualitatively, the desynchronizations in the encoding and maintenance phases appeared to be stronger and more widespread in the left DLPFC stimulation condition as compared to the right DLPFC and sham conditions. In contrast, the synchronization observed in the occipital cortices (during maintenance) was more widespread in the sham stimulation condition as compared to the 2 active tDCS conditions.

Figure 3.

Neural oscillatory responses during the VWM task. Time–frequency spectrogram displaying significant sensor level activity (top). Time is shown on the x-axis in milliseconds, and frequency is shown on the y-axis in Hz. Percent change in power is shown in the color bar above. We found an initial desynchronization in the alpha band during the encoding phase, followed by an alpha synchronization in the maintenance phase. Dotted white outlines indicate the extents of time–frequency windows that were subjected to source analysis. Grand averages across all participants in the maintenance and encoding time bins as a function of stimulation condition (bottom) showed a large desynchronization spanning from the lateral occipital to the parietal and temporal cortices in the left hemisphere in the encoding phase across all stimulation conditions. In the maintenance phase, a large desynchronization was centered on the left DLPFC and left parietal regions, while a synchronization was present in the bilateral occipital cortices.

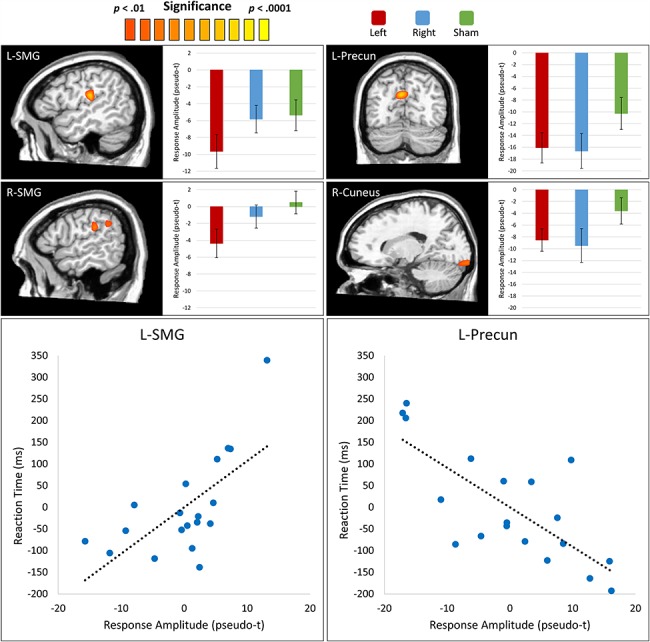

Effects of DLPFC ME-tDCS on Alpha-frequency VWM Responses

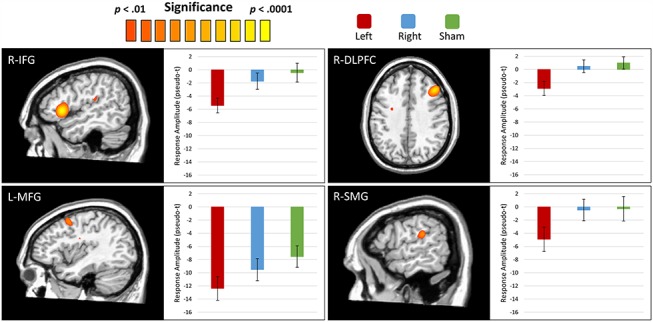

To statistically examine the effects of DLPFC ME-tDCS on the neural dynamics underlying VWM function, we used the participant-level whole-brain encoding and maintenance maps to compute repeated-measures ANOVAs for the alpha encoding and maintenance responses. Pseudo-t amplitude values were then extracted from the peak voxel of significant clusters and subjected to post hoc t-tests to identify the direction of the ME-tDCS condition effects. For the alpha encoding response, we found robust stimulation condition effects in the left and right supramarginal gyri, left precuneus, and the right cuneus, among others (Fig. 4). Post hoc analyses for these alpha encoding effects revealed that left DLPFC stimulation elicited a more robust response in the left and right supramarginal gyri as compared to the right DLPFC and sham stimulation. Further, left and right DLPFCs stimulation induced a significantly stronger response as compared to sham in the left precuneus and the right cuneus. For the alpha maintenance responses, significant effects were observed in the right inferior frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus, the right DLPFC, and the right supramarginal gyrus (Fig. 5). Follow-up testing for these peaks revealed that all 4 displayed a similar pattern to the encoding peaks, whereby left DLPFC stimulation induced a significantly larger response as compared to right DLPFC and sham stimulation. Comprehensive repeated-measures ANOVA results for the encoding and maintenance responses can be found in Table S1.

Figure 4.

Effects of ME-tDCS on the alpha encoding response. (Top) Whole brain ANOVAs testing for differences in the alpha encoding response as a function of stimulation condition revealed significant clusters in the left supramarginal gyrus (L-SMG), right supramarginal gyrus (R-SMG), left precuneus (L-Precun), and right cuneus. Post hoc analyses revealed that there was significantly stronger desynchronization in the bilateral supramarginal gyri following left DLPFC stimulation as compared to right DLPFC and sham stimulation. Note that the bar graph displayed for the R-SMG peak corresponds to the more anterior of the 2 clusters shown. In contrast, ME-tDCS of both the left and right DLPFCs elicited a stronger desynchronization in the L-Precun and the right cuneus as compared to sham. Bars reflect the standard error of the mean. (Bottom) Partial correlation plots for RT and the L-SMG and L-Precun are displayed. Both regions displayed significant correlation with RT after stepwise multiple regression analysis.

Figure 5.

Effects of ME-tDCS on the alpha maintenance response. Whole brain ANOVAs testing for differences in the alpha maintenance response as a function of stimulation condition revealed significant clusters in the right inferior frontal gyrus (R-IFG), left middle frontal gyrus (L-MFG), right DLPFC (R-DLPFC), and right supramarginal gyrus (R-SMG). In all 4 regions, the left DLPFC stimulation condition elicited a significantly stronger desynchronization response as compared to the R-DLPFC stimulation and sham conditions. Bars reflect the standard error of the mean.

Finally, to investigate the relevance of these responses to VWM function, we extracted amplitude values from the peak voxel of each significant cluster in the ANOVAs and averaged these values across all stimulation conditions. We then entered these mean values into stepwise multiple regression models predicting behavioral performance metrics (i.e., RT and accuracy). We found significant relationships between RT and alpha encoding response amplitude in the left precuneus (rpartial = −0.75, P < 0.001) and left supramarginal gyrus (rpartial = 0.67, P = 0.003), with the variance explained by each response being distinct from the variance explained by the other. Essentially, a greater desynchronization in the precuneus predicted slower RTs, while a greater desynchronization in the left supramarginal gyrus predicted faster responses (Fig. 4, bottom). Additionally, a pairwise correlation between RT and the right supramarginal encoding response revealed a significant relationship (r = 0.48; P = 0.036) in the same direction as its homologue in the left hemisphere, and the left and right supramarginal responses were tightly coupled across participants (r = 0.82, P < 0.001). This suggests that the bilateral supramarginal responses shared a large amount of variance and thus were likely acting in concert. No significant relationships were identified between neural responses and RT in the maintenance period or between neural responses and accuracy in the encoding or maintenance periods.

Discussion

Despite a large literature examining the effects of neurostimulation of the prefrontal cortices on VWM function, there remains little consensus regarding the nature of such effects. Further, how such stimulation alters the neural dynamics has only rarely been investigated. Herein, we applied ME-tDCS to the right and left DLPFC of healthy participants who then performed an extensively validated VWM task during MEG to better understand the impact of ME-tDCS on cognitive function and the underlying neural dynamics, especially in regard to the function of the left and right DLPFC. Using advanced source-imaging and whole-brain statistical analysis, we found that stimulation of the left DLPFC modulates the activity of a number of regions associated with VWM processing. Moreover, activity in some of these regions robustly predicted VWM task performance, indicating the importance of these patterns of neural activity for VWM function.

We found a robust desynchronization in the alpha band in the encoding and maintenance phases of the VWM paradigm in left-lateralized brain regions, extending anteriorly from occipital to frontal regions. This alpha desynchronization is known to represent the active processing of visual stimuli (van Dijk et al. 2008; Jensen and Mazaheri 2010), and the left-lateralized pattern of such alpha activity is essential for VWM processing (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a, 2018b; Proskovec et al. 2018). Additionally, we observed a much more focal alpha/beta (12–18 Hz) synchronization in occipital regions during the maintenance period, likely representing the protection of encoded stimulus features through the active inhibition of incoming visual information (Jensen et al. 2002; Tuladhar et al. 2007; Händel et al. 2011; Bonnefond and Jensen 2012). More specifically, we observed extensive dynamics including a left-lateralized occipital to frontal shift in the alpha desynchronization response during the encoding phase of the task, with regional peaks in lateral occipital, supramarginal, and inferior frontal cortices, which is consistent with many previous VWM studies (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a, 2018b; Proskovec et al. 2018). As visual–verbal information was encoded and transmitted to higher level cortical areas for further processing, the wave of desynchronization moved from occipital to frontal cortices. Supporting this conceptualization, this desynchronization in frontal and supramarginal areas remained during the maintenance phase, when no visual stimuli were present. Despite being a decrease in amplitude from basal levels of alpha activity, the desynchronization patterns in the encoding and maintenance phases represent the activation of these areas (Klimesch et al. 2007; Jensen and Mazaheri 2010; Klimesch 2012), leading to an active disinhibition of these cortices during stimulus processing and maintenance. Additionally, the temporally coincident alpha synchronization observed in the occipital cortices was more confined to occipital visual regions and as mentioned above likely represented the active gating of stimuli in these neuronal populations to limit the intrusion and interference of visual information unrelated to the task (Jensen et al. 2002; Tuladhar et al. 2007; Händel et al. 2011; Bonnefond and Jensen 2012).

In regard to the effects of stimulation condition on these network dynamics, we found that left DLPFC stimulation was associated with an accentuated desynchronization across left-lateralized brain regions relative to the right DLPFC and sham stimulation conditions. The most robust effect was centered on the left supramarginal gyrus, a region integral to VWM performance (Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a, 2018b; Proskovec et al. 2018). These effects may be due to a higher amount of cortical disruption following stimulation of left DLPFC, a key region in VWM, and more brain areas being recruited to compensate for such a disruption. Intriguingly, a similar effect was also observed in the right supramarginal gyrus, such that stimulation over the left DLPFC was associated with stronger activity, here relative to both right DLPFC and sham stimulation. The activation of bilateral homologous cortices with increased cognitive load has been well-supported in older adults (Cabeza et al. 2002; Emery et al. 2008; Proskovec et al. 2016) and is thought to index the recruitment of additional neural resources to handle increases in cognitive load. Supporting this, slower behavioral responses on the task were associated with stronger alpha oscillatory responses in the right and left supramarginal gyrus.

In addition to the effects of left DLPFC stimulation on the bilateral supramarginal gyri and other regions, there was also a laterality invariant effect of stimulation in the inferior occipital cortex and the precuneus during encoding. In other words, the alpha desynchronization response in these early visual regions was greater for both the left and right DLPFC stimulation conditions, as compared to the sham condition. Due to the critical role of the bilateral DLPFC in executive function (Goldman-Rakic et al. 1992; Fried et al. 2014), these posterior visual effects could perhaps be a compensatory mechanism by which the stimuli are processed more extensively at an “earlier” stage of the visual pathway, or alternatively, it might represent the intrusion of extraneous visual information. Further research will be needed to elucidate this effect.

Behaviorally, there were no significant differences between stimulation conditions. This may be due to the relatively simple nature of the VWM task, combined with the high level of cognitive function that would be expected from our sample of healthy young adults. Thus, these participants may be able to adequately compensate for any minor disruptive influences, and future research might test this hypothesis by varying the cognitive load of a similar VWM task under similar stimulation conditions. Although no conditional effects of stimulation on behavior were observed, subsequent analyses using step-wise regressions revealed key relationships between RT and response amplitude in the left precuneus and left supramarginal gyrus. Intriguingly, the alpha response in these spatially disparate regions predicted RT in divergent directions, such that faster responding on the task was related to a larger desynchronization in the supramarginal and a weaker desynchronization in the precuneus. Additionally, activity in the right and left supramarginal shared a high amount of variance across participants, and response amplitude in the right supramarginal also covaried with RT independently. This supports our hypothesis that the recruitment of the right supramarginal was a compensatory mechanism to maintain adequate processing despite the disruption of activity by the left DLPFC stimulation.

Generally, the findings of this study are in line with the observations of others exploring ME-tDCS effects on WM dynamics. In 2 separate studies, Hill et al. (Hill et al. 2017, 2018) found no significant differences in task performance despite widespread differences in EEG activity. In addition, their meta-analysis of the tDCS literature also concluded that the benefits of tDCS are negligible, and the existence of this effect remains uncertain due to the small effect sizes found in many of the studies (Hill et al. 2016). Although our analyses revealed a potential link between the neural dynamics being modulated by ME-tDCS application and WM performance, we also found no difference in task performance as a function of stimulation condition. Importantly, these previous studies did not examine the differential impact of stimulating the left versus right DLPFC and thus did not report the same laterality-specific effects of ME-tDCS that we find here. This is critical, as VWM tasks such as the ones used here and in these previous works are known to preferentially recruit left-lateralized neural networks (Cabeza and Nyberg 2000; D'Esposito 2007; Rottschy et al. 2012; Heinrichs-Graham and Wilson 2015; McDermott et al. 2016a, 2016b; Proskovec et al. 2016, 2019; Wiesman et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2017; Embury et al. 2018a, 2018b; Proskovec et al. 2018). Additionally, our study used the exceptional spatio-temporal precision of MEG, which facilitated the imaging of frequency-specific responses to the cortical surface using a beamformer, and allowed us to examine the network effects of prefrontal ME-tDCS stimulation.

In regards to the underlying neural mechanisms that led to the observed tDCS effects, the link between alpha oscillations and neurotransmitters levels, such as local levels of GABA, is not yet fully understood. However, studies have revealed alpha modulation in the presence of GABA altering drugs (Campbell et al. 2014; Lozano-Soldevilla et al. 2014), and tDCS has been found to modulate regional GABA (Bachtiar et al. 2015). In the context of the systems-level results observed here, this could mean that tDCS of the left DLPFC interfered with local neurotransmission in this region, thus requiring compensation from other cortical areas implicated in VWM processing. Of note, this interpretation is speculative, and much more work is needed to determine the underlying neural mechanisms of tDCS, its influence on oscillatory activity, and how different oscillatory frequencies and cortical regions may interact as a direct and indirect result of tDCS.

Before closing, it is important to note the limitations of this study. For one, our VWM paradigm was relatively simple, and we did not see any differences in RT or accuracy across the different stimulation conditions. On the one hand, this was desirable because performance differences can complicate interpreting neural differences (i.e., do the neural differences simply reflect performance differences), but on the other, the lack of behavioral differences limits interpretation of some of the tDCS effects. Although speculative, the lack of behavioral differences may reflect that our healthy young adults were able to employ compensatory responses to maintain adequate performance, as several elements of our data support this interpretation. It is also important to note that lateralized neural responses are often observed in contralateral visual cortices during encoding and maintenance when stimuli are presented to one visual hemifield (Sauseng et al. 2009). We did not study the interaction between stimulus and tDCS laterality in this investigation, but it would be interesting to explore how VWM with ME-tDCS is modulated when stimuli are presented to one visual hemifield. Regardless, there is definitely motivation for future studies to incorporate more complex VWM paradigms that may have greater sensitivity to minor behavioral differences. Another limitation rests in the fact that we only investigated one amplitude and duration of stimulation, and future studies should examine stronger amplitudes and longer durations. It is also important to discuss the repeatability of our experimental manipulation and outcome metrics (i.e., tDCS and MEG). Although to our knowledge, there exists no comprehensive investigation of the intrasubject stability of MEG responses after tDCS, a number of previous studies have shown that multispectral MEG responses in general exhibit high reliability across repeated sessions (Muthukumaraswamy et al. 2010; Becker et al. 2012; Wilson et al. 2014; Tan et al. 2015, 2016; Recasens and Uhlhaas 2017). In contrast, very little work has been devoted to understanding the repeatability of neural changes induced by transcranial stimulation, and this should be a topic of future interest. Finally, although the use of ME-tDCS (rather than conventional tDCS) remains a strength of this study, we made no explicit comparison between the 2 methods. Thus, future studies might explore the differential impact of ME and conventional tDCS on VWM function to elucidate which of our findings might be attributable to this component of our study. Despite these limitations, the current findings suggest that ME-tDCS, and particularly anodal ME-tDCS of the left DLPFC, may potentially interfere with the oscillatory neural dynamics supporting VWM processing by forcing the left-lateralized language areas to devote more resources to task completion. In particular, this was observed in the form of a stronger desynchronization in left hemispheric language regions, as well as the additional recruitment of right hemisphere homologues. More studies will need to be conducted to further interpret the effects of ME-tDCS on different facets of cognition besides VWM, but our findings currently provide critical insight into the complex effects of ME-tDCS on VWM in humans and its potentially detrimental effects on such cognitive processes. Ultimately, this adds to the growing literature on the effects of ME-tDCS on cognitive function and allows us to better understand its effects through the lens of its specific impact on the underlying neurophysiology.

Supplementary Material

Funding

National Institutes of Health (grants R01-MH103220 to T.W.W., R01-MH116782 to T.W.W., RF1-MH117032 to T.W.W., R01-MH118013 to T.W.W., and F31-AG055332 to A.I.W.) and the National Science Foundation (grant 1539067 to T.W.W.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Bachtiar V, Near J, Johansen-Berg H, Stagg CJ. 2015. Modulation of gaba and resting state functional connectivity by transcranial direct current stimulation. Elife. 4:e08789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. 1992. Working memory. Science. 255:556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JT, Fabrizio M, Sudre G, Haridis A, Ambrose T, Aizenstein HJ, Eddy W, Lopez OL, Wolk DA, Parkkonen L. 2012. Potential utility of resting-state magnetoencephalography as a biomarker of cns abnormality in hiv disease. J Neurosci Methods. 206(2):176–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefond M, Jensen O. 2012. Alpha oscillations serve to protect working memory maintenance against anticipated distracters. Curr Biol. 22(20):1969–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunoni AR, Sampaio-Junior B, Moffa AH, Aparício LV, Gordon P, Klein I, Rios RM, Razza LB, Loo C, Padberg F et al. 2018. Noninvasive brain stimulation in psychiatric disorders: a primer. Braz J Psychiatr. 41(1):70–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Anderson ND, Locantore JK, McIntosh AR. 2002. Aging gracefully: compensatory brain activity in high-performing older adults. Neuroimage. 17(3):1394–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza R, Nyberg L. 2000. Imaging cognition ii: an empirical review of 275 pet and fmri studies. J Cogn Neurosci. 12(1):1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AE, Sumner P, Singh KD, Muthukumaraswamy SD. 2014. Acute effects of alcohol on stimulus-induced gamma oscillations in human primary visual and motor cortices. Neuropsychopharmacology. 39(9):2104–2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffman BA, Clark VP, Parasuraman R. 2014. Battery powered thought: enhancement of attention, learning, and memory in healthy adults using transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroimage. 85(Pt 3):895–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M. 2007. From cognitive to neural models of working memory. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 362(1481):761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A, Bansal V, Diaz J, Patel J, Reato D, Bikson M. 2009. Gyri-precise head model of transcranial direct current stimulation: improved spatial focality using a ring electrode versus conventional rectangular pad. Brain Stimul. 2(4):201–207207.e201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta A, Elwassif M, Battaglia F, Bikson M. 2008. Transcranial current stimulation focality using disc and ring electrode configurations: fem analysis. J Neural Eng. 5(2):163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards D, Cortes M, Datta A, Minhas P, Wassermann EM, Bikson M. 2013. Physiological and modeling evidence for focal transcranial electrical brain stimulation in humans: a basis for high-definition tdcs. Neuroimage. 74:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embury CM, Wiesman AI, Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, McDermott TJ, Lord GH, Brau KL, Drincic AT, Desouza CV, Wilson TW. 2018a. Altered brain dynamics in patients with type 1 diabetes during working memory processing. Diabetes. 67(6):1140–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embury CM, Wiesman AI, Proskovec AL, Mills MS, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wang YP, Calhoun VD, Stephen JM, Wilson TW. 2018b. Neural dynamics of verbal working memory processing in children and adolescents. Neuroimage. 185:191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery L, Heaven TJ, Paxton JL, Braver TS. 2008. Age-related changes in neural activity during performance matched working memory manipulation. Neuroimage. 42(4):1577–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M. 2004. Permutation methods: A basis for exact inference. Statist Sci. 19(4):676–685. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci R, Marceglia S, Vergari M, Cogiamanian F, Mrakic-Sposta S, Mameli F, Zago S, Barbieri S, Priori A. 2008. Cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation impairs the practice-dependent proficiency increase in working memory. J Cogn Neurosci. 20(9):1687–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fertonani A, Miniussi C. 2017. Transcranial electrical stimulation: what we know and do not know about mechanisms. Neuroscientist. 23(2):109–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmer HL, Dux PE, Mattingley JB. 2014. Applications of transcranial direct current stimulation for understanding brain function. Trends Neurosci. 37(12):742–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PJ, Rushmore RJ, Moss MB, Valero-Cabré A, Pascual-Leone A. 2014. Causal evidence supporting functional dissociation of verbal and spatial working memory in the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 39(11):1973–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS, Bates JF, Chafee MV. 1992. The prefrontal cortex and internally generated motor acts. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2(6):830–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Kujala J, Hamalainen M, Timmermann L, Schnitzler A, Salmelin R. 2001. Dynamic imaging of coherent sources: studying neural interactions in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 98(2):694–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E, McDermott TJ, Mills MS, Coolidge NM, Wilson TW. 2017. Transcranial direct-current stimulation modulates offline visual oscillatory activity: a magnetoencephalography study. Cortex. 88:19–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2015. Spatiotemporal oscillatory dynamics during the encoding and maintenance phases of a visual working memory task. Cortex. 69:121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE. 2016. Effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory: a systematic review and meta-analysis of findings from healthy and neuropsychiatric populations. Brain Stimul. 9(2):197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Rogasch NC, Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE. 2017. Effects of prefrontal bipolar and high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation on cortical reactivity and working memory in healthy adults. Neuroimage. 152:142–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AT, Rogasch NC, Fitzgerald PB, Hoy KE. 2018. Effects of single versus dual-site high-definition transcranial direct current stimulation (hd-tdcs) on cortical reactivity and working memory performance in healthy subjects. Brain Stimul. 11(5):1033–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand A, Singh KD, Holliday IE, Furlong PL, Barnes GR. 2005. A new approach to neuroimaging with magnetoencephalography. Hum Brain Mapp. 25(2):199–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Händel BF, Haarmeier T, Jensen O. 2011. Alpha oscillations correlate with the successful inhibition of unattended stimuli. J Cogn Neurosci. 23(9):2494–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Gelfand J, Kounios J, Lisman JE. 2002. Oscillations in the alpha band (9-12 hz) increase with memory load during retention in a short-term memory task. Cereb Cortex. 12(8):877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Mazaheri A. 2010. Shaping functional architecture by oscillatory alpha activity: gating by inhibition. Front Hum Neurosci. 4:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempe R, Huang Y, Parra LC. 2014. Simulating pad-electrodes with high-definition arrays in transcranial electric stimulation. J Neural Eng. 11(2):026003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Stephenson MC, Morris PG, Jackson SR. 2014. Tdcs-induced alterations in gaba concentration within primary motor cortex predict motor learning and motor memory: a 7 t magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuroimage. 99:237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W. 2012. Α-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends Cogn Sci. 16(12):606–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimesch W, Sauseng P, Hanslmayr S. 2007. Eeg alpha oscillations: the inhibition-timing hypothesis. Brain Res Rev. 53(1):63–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HI, Bikson M, Datta A, Minhas P, Paulus W, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. 2013. Comparing cortical plasticity induced by conventional and high-definition 4 × 1 ring tdcs: a neurophysiological study. Brain Stimul. 6(4):644–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Jung YJ, Lee SJ, Im CH. 2017. Comets2: an advanced matlab toolbox for the numerical analysis of electric fields generated by transcranial direct current stimulation. J Neurosci Methods. 277:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebetanz D, Nitsche MA, Tergau F, Paulus W. 2002. Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial dc-stimulation-induced after-effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain. 125(Pt 10):2238–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Soldevilla D, Huurne N, Cools R, Jensen O. 2014. Gabaergic modulation of visual gamma and alpha oscillations and its consequences for working memory performance. Curr Biol. 24(24):2878–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso LE, Ilieva IP, Hamilton RH, Farah MJ. 2016. Does transcranial direct current stimulation improve healthy working memory?: a meta-analytic review. J Cogn Neurosci. 28(8):1063–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel AL, Schnider A. 2016. Effect of prefrontal and parietal tdcs on learning and recognition of verbal and non-verbal material. Clin Neurophysiol. 127(7):2592–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E, Oostenveld R. 2007. Nonparametric statistical testing of eeg- and meg-data. J Neurosci Methods. 164(1):177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L, Mölle M, Siebner HR, Born J. 2005. Bifrontal transcranial direct current stimulation slows reaction time in a working memory task. BMC Neurosci. 6:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott TJ, Badura-Brack AS, Becker KM, Ryan TJ, Bar-Haim Y, Pine DS, Khanna MM, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2016a. Attention training improves aberrant neural dynamics during working memory processing in veterans with ptsd. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 16(6):1140–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott TJ, Badura-Brack AS, Becker KM, Ryan TJ, Khanna MM, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2016b. Male veterans with ptsd exhibit aberrant neural dynamics during working memory processing: an meg study. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 41(4):251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott TJ, Wiesman AI, Mills MS, Spooner RK, Coolidge NM, Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2019. Tdcs modulates behavioral performance and the neural oscillatory dynamics serving visual selective attention. Hum Brain Mapp. 40(3):729–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzuyanim-Gorlick S, Mashal N. 2016. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on cognitive inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 234(6):1537–1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumaraswamy SD, Singh KD, Swettenham JB, Jones DK. 2010. Visual gamma oscillations and evoked responses: variability, repeatability and structural mri correlates. Neuroimage. 49(4):3349–3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Antal A, Tergau F, Paulus W. 2003a. Safety criteria for transcranial direct current stimulation (tdcs) in humans. Clin Neurophysiol. 114(11):2220–2222author reply 2222–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Nitsche MS, Klein CC, Tergau F, Rothwell JC, Paulus W. 2003b. Level of action of cathodal dc polarisation induced inhibition of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol. 114(4):600–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Paulus W. 2000. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 527(Pt 3):633–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Paulus W. 2001. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial dc motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology. 57(10):1899–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsche MA, Seeber A, Frommann K, Klein CC, Rochford C, Nitsche MS, Fricke K, Liebetanz D, Lang N, Antal A et al. 2005. Modulating parameters of excitability during and after transcranial direct current stimulation of the human motor cortex. J Physiol. 568(Pt 1):291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Dan H, Sakamoto K, Takeo K, Shimizu K, Kohno S, Oda I, Isobe S, Suzuki T, Kohyama K et al. 2004. Three-dimensional probabilistic anatomical cranio-cerebral correlation via the international 10-20 system oriented for transcranial functional brain mapping. Neuroimage. 21(1):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Dan I. 2005. Automated cortical projection of head-surface locations for transcranial functional brain mapping. Neuroimage. 26(1):18–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2016. Aging modulates the oscillatory dynamics underlying successful working memory encoding and maintenance. Hum Brain Mapp. 37(6):2348–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2019. Load modulates the alpha and beta oscillatory dynamics serving verbal working memory. Neuroimage. 184:256–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proskovec AL, Wiesman AI, Heinrichs-Graham E, Wilson TW. 2018. Beta oscillatory dynamics in the prefrontal and superior temporal cortices predict spatial working memory performance. Sci Rep. 8(1):8488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recasens M, Uhlhaas PJ. 2017. Test–retest reliability of the magnetic mismatch negativity response to sound duration and omission deviants. Neuroimage. 157:184–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottschy C, Langner R, Dogan I, Reetz K, Laird AR, Schulz JB, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. 2012. Modelling neural correlates of working memory: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Neuroimage. 60(1):830–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux F, Uhlhaas PJ. 2014. Working memory and neural oscillations: Α-γ versus θ-γ codes for distinct wm information? Trends Cogn Sci. 18(1):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffini G, Fox MD, Ripolles O, Miranda PC, Pascual-Leone A. 2014. Optimization of multifocal transcranial current stimulation for weighted cortical pattern targeting from realistic modeling of electric fields. Neuroimage. 89:216–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauseng P, Klimesch W, Heise KF, Gruber WR, Holz E, Karim AA, Glennon M, Gerloff C, Birbaumer N, Hummel FC. 2009. Brain oscillatory substrates of visual short-term memory capacity. Curr Biol. 19(21):1846–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg CJ, Best JG, Stephenson MC, O'Shea J, Wylezinska M, Kincses ZT, Morris PG, Matthews PM, Johansen-Berg H. 2009. Polarity-sensitive modulation of cortical neurotransmitters by transcranial stimulation. J Neurosci. 29(16):5202–5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H-R, Gross J, Uhlhaas P. 2015. Meg—measured auditory steady-state oscillations show high test–retest reliability: a sensor and source-space analysis. Neuroimage. 122:417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H-R, Gross J, Uhlhaas P. 2016. Meg sensor and source measures of visually induced gamma-band oscillations are highly reliable. Neuroimage. 137:34–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S, Simola J. 2006. Spatiotemporal signal space separation method for rejecting nearby interference in meg measurements. Phys Med Biol. 51(7):1759–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taulu S, Simola J, Kajola M. 2005. Applications of the signal space separation method. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 53(9):3359–3372. [Google Scholar]

- Tuladhar AM, Huurne N, Schoffelen JM, Maris E, Oostenveld R, Jensen O. 2007. Parieto-occipital sources account for the increase in alpha activity with working memory load. Hum Brain Mapp. 28(8):785–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uusitalo MA, Ilmoniemi RJ. 1997. Signal-space projection method for separating meg or eeg into components. Med Biol Eng Comput. 35(2):135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijk H, Schoffelen JM, Oostenveld R, Jensen O. 2008. Prestimulus oscillatory activity in the alpha band predicts visual discrimination ability. J Neurosci. 28(8):1816–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Veen BD, van Drongelen W, Yuchtman M, Suzuki A. 1997. Localization of brain electrical activity via linearly constrained minimum variance spatial filtering. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 44(9):867–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman AI, Heinrichs-Graham E, McDermott TJ, Santamaria PM, Gendelman HE, Wilson TW. 2016. Quiet connections: reduced fronto-temporal connectivity in nondemented parkinson's disease during working memory encoding. Hum Brain Mapp. 37(9):3224–3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesman AI, Mills MS, McDermott TJ, Spooner RK, Coolidge NM, Wilson TW. 2018. Polarity-dependent modulation of multi-spectral neuronal activity by transcranial direct current stimulation. Cortex. 108:222–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Heinrichs-Graham E, Becker KM. 2014. Circadian modulation of motor-related beta oscillatory responses. Neuroimage. 102(Pt 2):531–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, McDermott TJ, Mills MS, Coolidge NM, Heinrichs-Graham E. 2018. Tdcs modulates visual gamma oscillations and basal alpha activity in occipital cortices: evidence from meg. Cereb Cortex. 28(5):1597–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TW, Proskovec AL, Heinrichs-Graham E, O'Neill J, Robertson KR, Fox HS, Swindells S. 2017. Aberrant neuronal dynamics during working memory operations in the aging hiv-infected brain. Sci Rep. 7:41568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.