Abstract

Background

Whilst the pharmacological profiles and mechanisms of antidepressants are varied, there are common reasons why they might help people to stop smoking tobacco. Firstly, nicotine withdrawal may produce depressive symptoms and antidepressants may relieve these. Additionally, some antidepressants may have a specific effect on neural pathways or receptors that underlie nicotine addiction.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the efficacy, safety and tolerability of medications with antidepressant properties in assisting long‐term tobacco smoking cessation in people who smoke cigarettes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Specialized Register, which includes reports of trials indexed in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO, clinicaltrials.gov, the ICTRP, and other reviews and meeting abstracts, in May 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that recruited smokers, and compared antidepressant medications with placebo or no treatment, an alternative pharmacotherapy, or the same medication used in a different way. We excluded trials with less than six months follow‐up from efficacy analyses. We included trials with any follow‐up length in safety analyses.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data and assessed risk of bias using standard Cochrane methods. We also used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

The primary outcome measure was smoking cessation after at least six months follow‐up, expressed as a risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence available in each trial, and biochemically validated rates if available. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model.

Similarly, we presented incidence of safety and tolerance outcomes, including adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), psychiatric AEs, seizures, overdoses, suicide attempts, death by suicide, all‐cause mortality, and trial dropout due to drug, as RRs (95% CIs).

Main results

We included 115 studies (33 new to this update) in this review; most recruited adult participants from the community or from smoking cessation clinics. We judged 28 of the studies to be at high risk of bias; however, restricting analyses only to studies at low or unclear risk did not change clinical interpretation of the results. There was high‐certainty evidence that bupropion increased long‐term smoking cessation rates (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.52 to 1.77; I2 = 15%; 45 studies, 17,866 participants). There was insufficient evidence to establish whether participants taking bupropion were more likely to report SAEs compared to those taking placebo. Results were imprecise and CIs encompassed no difference (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.48; I2 = 0%; 21 studies, 10,625 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence, downgraded one level due to imprecision). We found high‐certainty evidence that use of bupropion resulted in more trial dropouts due to adverse events of the drug than placebo (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.56; I2 = 19%; 25 studies, 12,340 participants). Participants randomized to bupropion were also more likely to report psychiatric AEs compared with those randomized to placebo (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.37; I2 = 15%; 6 studies, 4439 participants).

We also looked at the safety and efficacy of bupropion when combined with other non‐antidepressant smoking cessation therapies. There was insufficient evidence to establish whether combination bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) resulted in superior quit rates to NRT alone (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.51; I2 = 52%; 12 studies, 3487 participants), or whether combination bupropion and varenicline resulted in superior quit rates to varenicline alone (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.55; I2 = 15%; 3 studies, 1057 participants). We judged the certainty of evidence to be low and moderate, respectively; in both cases due to imprecision, and also due to inconsistency in the former. Safety data were sparse for these comparisons, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions.

A meta‐analysis of six studies provided evidence that bupropion resulted in inferior smoking cessation rates to varenicline (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.79; I2 = 0%; 6 studies, 6286 participants), whilst there was no evidence of a difference in efficacy between bupropion and NRT (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.09; I2 = 18%; 10 studies, 8230 participants).

We also found some evidence that nortriptyline aided smoking cessation when compared with placebo (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.48 to 2.78; I2 = 16%; 6 studies, 975 participants), whilst there was insufficient evidence to determine whether bupropion or nortriptyline were more effective when compared with one another (RR 1.30 (favouring bupropion), 95% CI 0.93 to 1.82; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 417 participants). There was no evidence that any of the other antidepressants tested (including St John's Wort, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)) had a beneficial effect on smoking cessation. Findings were sparse and inconsistent as to whether antidepressants, primarily bupropion and nortriptyline, had a particular benefit for people with current or previous depression.

Authors' conclusions

There is high‐certainty evidence that bupropion can aid long‐term smoking cessation. However, bupropion also increases the number of adverse events, including psychiatric AEs, and there is high‐certainty evidence that people taking bupropion are more likely to discontinue treatment compared with placebo. However, there is no clear evidence to suggest whether people taking bupropion experience more or fewer SAEs than those taking placebo (moderate certainty). Nortriptyline also appears to have a beneficial effect on smoking quit rates relative to placebo. Evidence suggests that bupropion may be as successful as NRT and nortriptyline in helping people to quit smoking, but that it is less effective than varenicline. There is insufficient evidence to determine whether the other antidepressants tested, such as SSRIs, aid smoking cessation, and when looking at safety and tolerance outcomes, in most cases, paucity of data made it difficult to draw conclusions. Due to the high‐certainty evidence, further studies investigating the efficacy of bupropion versus placebo are unlikely to change our interpretation of the effect, providing no clear justification for pursuing bupropion for smoking cessation over front‐line smoking cessation aids already available. However, it is important that where studies of antidepressants for smoking cessation are carried out they measure and report safety and tolerability clearly.

Plain language summary

Do medicines used to treat depression help people to quit smoking?

Background and review questions

Some medicines and supplements that have been used to treat depression (antidepressants) have also been tested to see whether they can help people to stop smoking. Two of these treatments ‐ bupropion (sometimes called Zyban) and nortriptyline ‐ are sometimes given to help people quit smoking. This review looks at whether using antidepressants actually helps people to stop smoking (for six months or longer), and also looks at the safety of using these medicines.

Study characteristics

This review includes 115 studies looking at how helpful and safe different antidepressants are when used to quit smoking. Most of the studies were conducted in adults. We included studies of any length when looking at safety, but studies needed to be at least six months long when assessing whether people had managed to quit smoking. The evidence is up to date to May 2019.

Key results

Using the antidepressant, bupropion, makes it 52% to 77% more likely that a person will successfully stop smoking, which is equal to five to seven more people successfully quitting for six months or more for every one hundred people who try to quit. There is evidence that people who use the antidepressant, nortriptyline, to quit smoking also improve their chances of success. There is not enough evidence to determine whether other antidepressants help people to quit smoking.

There is evidence that bupropion increases unwanted effects, particularly those relating to mental health, and that unwanted effects may increase the chance that people stop using the medicine. However, the evidence does not suggest that bupropion is more likely to result in death, hospitalization, or life‐threatening events, like seizures. There is not enough information to draw clear conclusions about the safety of nortriptyline for stopping smoking.

The evidence does not suggest that taking bupropion at the same time as other stop‐smoking medicines, like varenicline (sometimes known as Champix or Chantix) or nicotine replacement therapy makes people more likely to quit smoking. People are as likely to quit smoking when using bupropion as when using nortriptyline or nicotine replacement therapy, however people using varenicline are more likely to quit than those using bupropion.

Certainty of evidence

There is high‐certainty evidence that bupropion helps people to quit smoking, meaning further research is very unlikely to change this conclusion. However, there is also high‐certainty evidence to suggest that people using bupropion are more likely to stop taking the medicine because of unpleasant effects than those taking a pill without medication (a placebo). The certainty of the evidence was moderate, low or very low for the other key questions we looked at. This means that the findings of those questions may change when more research is carried out. In most cases this was because there were not enough studies or studies were too small.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Tobacco use is one of the leading causes of preventable illness and death worldwide, accounting for over eight million deaths annually (GBD RFC 2017). Extrapolation based on current smoking trends, suggests that without widespread quitting, approximately 400 million tobacco‐related deaths will occur between 2010 and 2050, mostly among current smokers (Jha 2011). Most smokers would like to stop (CDC 2017); however, quitting tobacco use is difficult. This is because users develop both a psychological and physiological dependence on smoking. The physiological dependence is caused by a component of tobacco, called nicotine (McNeill 2017).

Description of the intervention

Whilst antidepressant medications are primarily used for the treatment of depression and disorders of negative affect, they have also been used to help individuals stop smoking. They offer an alternative to other frontline smoking cessation therapies, such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), and nicotine agonists, such as varenicline.

The following medications and substances, regarded as having antidepressant properties, have been investigated for their effect on smoking cessation in at least one study.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): doxepin, imipramine and nortriptyline

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): moclobemide, selegiline, lazabemide, and EVT302

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and zimeledine

Atypical antidepressants: bupropion, tryptophan, venlafaxine

Extracts of St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L)

Dietary supplement: S‐Adenosyl‐L‐Methionine (SAMe)

Of the antidepressant medications indicated for smoking cessation, the most commonly used is bupropion. It has both dopaminergic and adrenergic actions, and appears to be an antagonist at the nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptor (Fryer 1999). It has been licensed as a prescription aid to smoking cessation in many countries. The usual dose for smoking cessation is 150 mg once a day for three days, increasing to 150 mg twice a day continued for 7 to 12 weeks, and quit attempts are generally initiated one week after starting pharmacotherapy.

Following bupropion, the second most commonly tested medication for smoking cessation is the TCA, nortriptyline. It enhances noradrenergic and serotonergic activity by blocking reuptake of these neurotransmitters (Benowitz 2000). It is licensed for smoking cessation in New Zealand. The recommended regimen is 10 to 28 days of titration before the quit attempt, followed by a 12‐week dose of 75 mg to 100 mg daily (Cahill 2013).

No other antidepressants are currently licensed for use as smoking cessation aids, although others have been tested for possible use.

How the intervention might work

Multiple observations have provided a rationale for studying the effects of antidepressant medications for smoking cessation: a history of depression is found more frequently amongst smokers than nonsmokers, nicotine may have antidepressant effects, and antidepressants influence the neurotransmitters and receptors involved in nicotine addiction (Benowitz 2000; Kotlyar 2001). It has also been hypothesized that cessation may precipitate depression, however evidence suggests that this is unlikely to be the case, and that cessation may actually reduce the likelihood of depression (Taylor 2014).

The diverse pharmacological targets of antidepressants means their mechanisms of action are varied. Evidence suggests bupropion may aid smoking cessation by blocking nicotine effects, relieving withdrawal (Cryan 2003; West 2008), and reducing depressed mood (Lerman 2002a). Monoamine oxidase‐A (MOA‐A) inhibitors may aid smoking cessation by substituting the ability of smoking to act as a MOA inhibitor (Lewis 2007). It has been hypothesized that SSRIs might be helpful because they increase serotonin, which is also associated with improving negative affect (Benowitz 2000). The mechanisms of other antidepressants for smoking cessation remain unstudied.

Although there is an evident relationship between alleviating negative affect and antidepressant pharmacology, it is unclear whether antidepressants work mostly due to reducing negative affect, reducing urges to smoke or withdrawal symptoms, or by acting as nicotine blockers.

Why it is important to do this review

The ongoing impact of smoking on global morbidity and mortality necessitates effective and safe treatments to aid smoking cessation. Since the last update of this review was published in 2014 (Hughes 2014), a substantial amount of new evidence has emerged to assess antidepressants as smoking cessation aids. This has the potential to change or strengthen our conclusions regarding the efficacy of some of these antidepressants when compared with no treatment, whilst also strengthening the evidence regarding the safety of those antidepressant currently being used to help people quit smoking (bupropion and nortriptyline). Further evidence on safety outcomes may help to clarify the potential interaction between bupropion and seizures, as well as psychiatric adverse events. Multiple trials and observational studies have previously associated bupropion with increasing the risk of medically important adverse events, including seizures, anxiety, depression, and insomnia (Aubin 2012). New evidence may also help us to directly compare the safety and efficacy of antidepressants with other front‐line smoking cessation medications, providing a further aid to decision making when helping people to quit tobacco smoking.

Objectives

To assess the evidence for the efficacy, safety and tolerability of medications with antidepressant properties in assisting long‐term tobacco smoking cessation in people who smoke cigarettes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We included tobacco smokers of any age, with or without a history of mental illness. We did not include pregnant women, as these smokers are covered in a separate Cochrane Review (Coleman 2015).

Types of interventions

We included trials studying pharmacotherapies with antidepressant properties for smoking cessation. We included trials assessing different doses, durations and schedules of antidepressants.

We excluded trials where an additional, uncontrolled non‐antidepressant intervention component was used in only one of the trial arms. This is because the confounding effects of this intervention would have made it difficult to determine whether any change in outcome was related to the antidepressant or the confounding intervention component. Additionally, we excluded trials investigating antidepressant use for smoking harm reduction or relapse prevention, as they are covered elsewhere (Lindson‐Hawley 2016 and Livingstone‐Banks 2019, respectively).

Comparators

The following comparators were eligible for assessing safety, efficacy and tolerability: placebo, no pharmacotherapy, alternative therapeutic control, or different dosages/treatment regimes of the same antidepressant.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Efficacy, measured as smoking cessation

For this outcome we only included studies that set out to report smoking cessation rates at least six months after baseline, in line with the standard methods of Cochrane Tobacco Addiction. Where cessation was assessed at multiple intervals, we report only the longest follow‐up data. Additionally, where multiple definitions of abstinence are assessed, we report the strictest of these definitions (e.g. continuous/prolonged abstinence over point prevalence abstinence). We also report biochemical validation of abstinence over self‐reported abstinence (but it was not necessary for abstinence to have been biochemically validated for a study to be included).

Secondary outcomes

-

Safety, measured as:

number of people experiencing adverse events (AEs) of any severity (e.g. abnormal test findings, clinically significant symptoms and signs, changes in physical examination findings, hypersensitivity, and progression or worsening of underlying disease)

number of people experiencing psychiatric AEs (e.g. adverse events relating to mental health)

number of people experiencing serious adverse events (SAEs), i.e. events that result in death, are life‐threatening (immediate risk of death), require inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, result in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, and/or result in congenital anomaly or birth defect (e.g. seizures, overdoses, suicide attempts, death by suicide, all‐cause mortality).

We also recorded the following SAEs specifically, as these have previously been associated with the use of antidepressants for smoking cessation.

Number of people experiencing seizures

Number of people experiencing overdoses

Number of people experiencing suicide attempts

Number of people experiencing death by suicide

Number of people experiencing all‐cause mortality

Tolerability, measured as the number of participants who dropped out of the trial due to adverse events

For all safety and tolerability outcomes, we considered studies with follow‐up of any length.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified studies from the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Specialized Register. At the time of the updated search in May 2019, the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 4); MEDLINE (via OVID) to update April 2019; Embase (via OVID) to April 2019; PsycINFO (via OVID) to update April 2019; US National Library of Medicine to April 2019. See the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction website for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched to populate the Register. We searched the Register for reports of studies evaluating bupropion, nortriptyline or any other pharmacotherapy classified as having an antidepressant effect. Search terms included relevant individual drug names or antidepressant* or antidepressive*. See Appendix 1 for the Register search strategy.

Searching other resources

We searched ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov) and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) through the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Specialized Register.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (of JHB, JLB, NL, SH) independently screened titles and abstracts resulting from our searches for relevance, and obtained full‐text records of reports of eligible or possibly eligible studies. Two review authors (of JHB, JLB, NL, SH) then independently screened each full‐text record for eligibility. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third review author. For conference abstracts or trial registry entries where the record contained insufficient evidence for us to determine the eligibility of the study, we attempted to contact study investigators to obtain any additional data needed to make a final decision. We recorded all screening decisions made and presented the flow of studies and references through the reviewing process using a PRISMA flow diagram (Moher 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (of BH, JHB, JLB, NL, SH) independently extracted the following study data and compared the findings. Any discrepancies were resolved by mutual consent.

Type of antidepressant

Country and setting

Recruitment method

Definition of smoker used

Participant demographics (i.e. average age, gender, average cigarettes per day)

Intervention and control description (including dose, schedule, and behavioural support common to all arms)

Efficacy outcome(s) used in meta‐analysis, including length of follow‐up, definition of abstinence, and biochemical validation of smoking cessation

Any analysis investigating the interaction between efficacy and participants' depression status

Safety and tolerability outcomes, including AEs, psychiatric AEs, SAEs, types of SAEs, withdrawals due to treatment

Sources of funding and declarations of interest

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed included studies for risks of selection bias (method of random sequence generation and allocation concealment), bias due to an absence of blinding (taking into account both performance and detection bias in a single domain), attrition bias (levels and reporting of loss to follow‐up), and any other threats to study validity, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). For each new study in this update, two review authors (of JHB, JLB, NL, SH) independently assessed each study for each domain, in accordance with 'Risk of bias' guidance developed by Cochrane Tobacco Addiction to assess smoking cessation studies. Where there was any disagreement on the assessment, it was resolved through discussion with a third review author.

We considered studies at high risk of performance and detection bias where there was no blinding of participants or personnel or where there was evidence of unblinding; at unclear risk if insufficient information was available with which to judge; and at low risk if the study reported blinding of participants and personnel in detail and there was no evidence of unblinding. We considered studies to be at low risk of attrition bias where over half of the participants were followed up at the longest follow‐up and where numbers followed up were similar across arms (difference < 20%).

Measures of treatment effect

Smoking cessation

We calculated cessation rates for all studies that reported cessation at least six months following baseline. For each study, we used the strictest available criteria to define cessation as described above.

Where data were available, we expressed cessation as a risk ratio (RR) for each study. We calculated this as follows: (quitters in treatment group/total randomized to treatment group)/(quitters in control group/total randomized to control group), alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A RR > 1 indicates increased likelihood of quitting in the intervention group than in the control condition.

Adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs)

We calculated AE rates for all studies that reported adequate data, regardless of study length. Where numerical data were available, we expressed safety and tolerability data as RRs (95% CI). We calculated this as follows: (number of participants reporting (S)AEs in treatment group/total randomized to treatment group)/(number of participants reporting (S)AEs in control group/total randomized to control group). A RR > 1 indicates an increased likelihood of experiencing an AE or SAE in the intervention group than in the control condition.

In addition to overall AEs and overall SAEs, we calculated RRs (95% CI) for the following safety and tolerability outcomes, where data were available.

Psychiatric AEs

Seizures

Overdoses

Suicide attempts

Death by suicide

All‐cause mortality

Dropout due to adverse events

Insomnia

Anxiety

Unit of analysis issues

We only judged one cluster‐RCT to be eligible for inclusion (Siddiqi 2013). This study was not pooled in any meta‐analysis due to substantial heterogeneity of programme effects across clusters.

Dealing with missing data

As far as possible, we used an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis with people who dropped out or were lost to follow‐up treated as continuing smokers. Where participants appeared to have been randomized, but were not included in the data presented by the authors (and we were unable to obtain these), we noted this in the study description (see Characteristics of included studies). We extracted numbers lost to follow‐up from study reports and used these to assess the risk of attrition bias.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Before pooling studies, we considered both methodological and clinical variance between studies. Where pooling was deemed appropriate we investigated statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This describes the percentage variability in effect estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (chance).

Assessment of reporting biases

Where a comparison included a sufficient number of studies (≥ 10), we generated funnel plots to analyse and report on potential publication bias as advised by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019).

We therefore generated funnel plots for the following comparisons.

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ smoking cessation

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ AEs

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ SAEs

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ seizures

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ suicide attempts

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ death by suicide

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ all‐cause mortality

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ dropout due to drug

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ anxiety

Bupropion versus placebo/control ‐ insomnia

Bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone ‐ smoking cessation

Bupropion versus NRT ‐ smoking cessation

Data synthesis

For each type of medication and comparison where more than one eligible trial was identified, we performed separate meta‐analyses of cessation and safety outcomes using Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect methods. We pooled RRs and 95% CIs from individual study estimates to estimate pooled RRs (95% CIs). Where studies contributed more than one intervention arm to a pooled analysis, we split the control arm to avoid double‐counting.

We also carried out post hoc, exploratory analyses to inform our approach to safety and tolerance for the next update of this review. We combined the following comparisons when evaluating AEs, psychiatric AEs, SAEs, and dropouts due to adverse effects.

Bupropion compared to placebo/control

Bupropion plus NRT compared to NRT alone

Bupropion plus varenicline compared to varenicline alone

The rationale for this was that these studies all tested the additional effect of bupropion, and there was no evidence of an interaction for safety and tolerability outcomes (whereas there may be for effectiveness). We subgrouped studies by their comparison type, though acknowledge that these subgroups may currently be underpowered to detect differences between groups.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For comparisons where we had sufficient data, we separated participant data into the following subgroups to determine whether antidepressants had differential effects on the relevant population or intervention groups.

Split by mental health diagnoses: mental health diagnoses versus no mental health diagnoses

Split by level of behavioural support: multisession group support versus multisession individual counselling versus low intensity support versus not specified. To be identified as low intensity, support had to be regarded as part of the provision of routine care, i.e. time spent with smoker (including assessment for the trial) less than 30 minutes at the initial consultation, with no more than two further assessment and reinforcement visits.

Where reported, we also extracted data from analyses evaluating a potential interaction between current depression or past history of depression and quit rates. We relied upon the definition of depression used by study authors, which included both formal diagnoses and scores on validated depression scales. This interaction is investigated in more detail in van der Meer 2013.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses.

We excluded studies from meta‐analyses that were judged to be at high risk of bias for any of the assessed bias domains. We judged whether this exclusion notably altered the pooled RRs (95% CI).

We excluded studies from meta‐analyses with industry support. We did this in two stages: 1) we excluded studies that were funded by the pharmaceutical industry; 2) we excluded studies that were funded by the pharmaceutical industry or where the study medication was provided by the pharmaceutical industry. We judged whether this exclusion notably altered the pooled RRs (95% CI).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created 'Summary of findings' tables using standard Cochrane methodology (Higgins 2019), for the following comparisons, which we judged to be most clinically relevant.

Bupropion compared to placebo/control

Bupropion plus NRT compared to NRT alone

Bupropion plus varenicline compared to varenicline alone

We judged these comparisons to be of most relevance because bupropion is currently the only antidepressant used as a front‐line therapy for smoking cessation worldwide.

Following standard Cochrane methodology (Higgins 2019), we used GRADEpro GDT software and the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for smoking cessation, SAEs, and dropout due to adverse events of the drug, and to draw conclusions about the certainty of the evidence within the text of the review (Schünemann 2013). We chose these outcomes as they are important factors to consider regarding pharmaceutical efficacy, safety and tolerability, and are therefore useful to both clinicians and patients when deciding whether to provide or use a smoking cessation pharmacotherapy.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

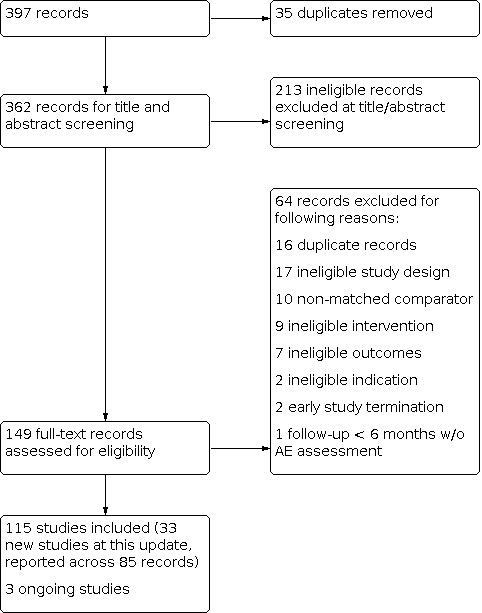

The most recent literature search for this update generated 397 records. After duplicates were removed, 362 records remained for title and abstract screening. We ruled out 213 records at this stage, leaving 149 records for full‐text screening. At this stage we identified 33 new, included studies (reported across 85 records in total) and three ongoing studies. See Figure 1 for full details of record/study flow information for the most recent updated search.

1.

Flow diagram for 2019 search update only

Included studies

We identified 33 additional eligible trials at this update, yielding a total of 115 included trials. The new trials studied:

bupropion: Anthenelli 2016; Benli 2017; Cinciripini 2018; CTRI/2013/07/003830; Ebbert 2014; Elsasser 2002; Fatemi 2013; Gilbert 2019; Gray 2011; Gray 2012; Johns 2017; Karam‐Hage 2011; Moreno‐Coutino 2015; NCT00132821; NCT00308763; NCT00495352; NCT00593099; NCT01406223; Perkins 2013; Rose 2014; Rose 2017; Sheng 2013; Singh 2010; Tidey 2011; Urdapilleta‐Herrera 2013; Weiner 2012; White 2005; Zincir 2013

EVT302: Berlin 2012

fluoxetine: Minami 2014; NCT00578669

lazabemide: Berlin 2002

St John’s wort: Barnes 2006

Further details of these newly included, as well as previously included studies, including dosing schedules, are recorded in the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Bupropion

Overall, we included 87 studies of bupropion. Outcomes for four of these studies are based only on conference abstracts or pharmaceutical company data (Ferry 1992; Ferry 1994; Selby 2003; SMK20001).

The majority of trials were conducted in North America, but we also included studies from Australia (Myles 2004); Brazil (Haggsträm 2006); China (Sheng 2013); Europe (Aubin 2004; Dalsgarð 2004; Fossati 2007; Górecka 2003; Rovina 2009; Stapleton 2013; Wagena 2005; Wittchen 2011; Zellweger 2005); India (CTRI/2013/07/003830; Johns 2017; Singh 2010); Israel (Planer 2011); New Zealand (Holt 2005); Pakistan (Siddiqi 2013); Taiwan (NCT00495352); and Turkey (Benli 2017; Uyar 2007; Zincir 2013). Three studies were carried out across multiple continents (Anthenelli 2016; Tonnesen 2003; Tonstad 2003).

A number of trials specifically recruited cohorts of participants with health conditions, including:

alcoholism (Grant 2007; Hays 2009; Karam‐Hage 2011)

bipolar disorder (NCT00593099)

cancer (Schnoll 2010)

cardiovascular disease (Eisenberg 2013; Planer 2011; Rigotti 2006; Tonstad 2003)

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Górecka 2003; Tashkin 2001; Wagena 2005)

mild depression (Moreno‐Coutino 2015)

psychiatric conditions (Anthenelli 2016)

schizophrenia (Evins 2001; Evins 2005; Evins 2007; Fatemi 2013; George 2002; George 2008; NCT00495352; Weiner 2012)

post‐traumatic stress disorder (Hertzberg 2001)

tuberculosis or suspected tuberculosis (Siddiqi 2013; CTRI/2013/07/003830)

Three of the studies in people with cardiovascular disease, and one other, enrolled hospital inpatients (Eisenberg 2013; Planer 2011; Rigotti 2006; Simon 2009).

Trials also studied specific populations of:

adolescents (Gray 2011; Gray 2012; Killen 2004; Muramoto 2007)

African‐Americans (Ahluwalia 2002; Cox 2012)

healthcare workers (Zellweger 2005)

hospital staff (Dalsgarð 2004)

low‐income and minority (NCT00308763)

Maori (Holt 2005)

males (Rose 2017)

smokers awaiting surgery (Myles 2004)

smokers who had previously failed to quit smoking using bupropion (Gonzales 2001; Selby 2003)

smokers who had just failed to quit using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (Hurt 2003; Rose 2013; Rose 2014).

More than half the bupropion studies followed participants for at least 12 months from the start of treatment or the target quit day. Twenty‐nine studies followed up participants for six months. The duration of follow‐up was below six months for 12 of the included studies, was of unknown duration for six studies, and one study measured number of days abstinent rather than numbers abstinent at a particular time point (Perkins 2013). However, these studies did measure safety outcomes; therefore they contributed data to our meta‐analyses of adverse events data, but not smoking cessation data.

In those studies which met or exceeded the six‐month follow‐up threshold, the majority reported an outcome of sustained (prolonged) abstinence. However, in 25 (33%) studies, only point prevalence rates were given, or the definition of abstinence was unclear.

Forty‐six trials evaluated bupropion for smoking cessation as a single pharmacotherapy versus placebo/non‐pharmacotherapeutic control, and three studies compared different doses of bupropion (Hurt 1997; Muramoto 2007; Swan 2003). Both Muramoto 2007 and Swan 2003 compared a 150 mg dose per day with a 300 mg dose per day, whereas Hurt 1997 looked at 100 mg per day versus 150 mg per day versus 300 mg per day. We pooled studies in which bupropion was used in combination with another pharmacotherapy or versus another pharmacotherapy in separate comparisons, as listed below.

Bupropion as an adjunct to NRT versus NRT alone (16 trials)

Bupropion as an adjunct to varenicline versus varenicline alone (6 trials)

Bupropion versus NRT (10 trials)

Bupropion versus varenicline (10 trials)

Bupropion versus nortriptyline (3 trials)

Bupropion versus gabapentin (1 trial)

Nortriptyline

We included 10 studies of the tricyclic antidepressant, nortriptyline in this review. Hall and colleagues conducted three trials (Hall 1998; Hall 2002; Hall 2004), and Prochazka and colleagues two (Prochazka 1998; Prochazka 2004), with all these trials conducted in the USA. One study was conducted in Australia (Richmond 2013), two in Brazil (Da Costa 2002; Haggsträm 2006), one in the Netherlands (Wagena 2005), and one in the UK (Aveyard 2008).

Richmond 2013 was the only study to be conducted in a specialist population, recruiting male prisoners who had been incarcerated for at least one month and had at least six months remaining of their sentences.

All studies were placebo controlled. They used nortriptyline doses of 75 mg/day to 100 mg/day or titrated doses to serum levels recommended for depression during the week prior to the quit date.

Treatment duration ranged from 12 to 14 weeks. Nearly all studies used a definition of cessation based on a sustained period of abstinence. Aveyard 2008, Hall 1998, Hall 2002, Hall 2004, and Richmond 2013 reported outcomes at ≥ 12 months of follow‐up and the other six studies had a maximum follow‐up of six months.

The three studies by Hall and colleagues used factorial designs to test nortriptyline versus placebo crossed with different intensities of behavioural support (Hall 1998; Hall 2002; Hall 2004). Conversely, the remaining studies provided a set amount of behavioural support to all participants, ranging from brief behavioural counselling to repeated group and individual sessions.

Six studies tested nortriptyline as a monotherapy, and four studies tested nortriptyline as an adjunct to NRT.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Fluoxetine

Seven studies of fluoxetine have been included in this review, with two of these studies identified for inclusion in the current update (Minami 2014; NCT00578669).

The majority of these trials took place in the USA (Brown 2014; Minami 2014; NCT00578669; Niaura 2002; Saules 2004; Spring 2007), and one in Iceland (Blondal 1999). Participants were recruited from clinics (Blondal 1999; Brown 2014; Niaura 2002; Saules 2004; Spring 2007), the community (Minami 2014), or through an unknown recruitment method (NCT00578669).

Brown 2014 was the only study to be conducted in a specialist population, recruiting smokers with elevated depressive symptoms.

Six of these studies conducted follow‐up to at least six months for cessation outcomes. Minami 2014 had a follow‐up duration of fewer than six months, so we only evaluated adverse events data for this study.

Four studies used varying doses of fluoxetine as a single pharmacotherapy: Niaura 2002 compared a 30 mg daily dose, a 60 mg daily dose, or placebo for 10 weeks; Spring 2007 used 60 mg or placebo for 12 weeks; NCT00578669 compared 20 mg daily for eight weeks preceding and following the target quit date to placebo. Minami 2014 also compared fluoxetine as a monotherapy (20 mg daily for 8 weeks prior to and following the target quit date) to placebo only.

The remaining three trials investigated fluoxetine as an adjunct to NRT, and used similar doses of fluoxetine: Blondal 1999 used 20 mg/day or placebo for three months as an adjunct to nicotine inhaler; Saules 2004 used 20 mg/day or 40 mg/day or placebo for 10 weeks as an adjunct to nicotine patch; and Brown 2014 compared 10 weeks of 20 mg daily fluoxetine, 16 weeks of 20 mg daily fluoxetine, or no additional treatment in participants using nicotine patch for eight weeks.

Paroxetine

One trial assessed paroxetine (20 mg, 40 mg or placebo) for nine weeks as an adjunct to nicotine patch (Killen 2000). It was conducted in the USA, with participants recruited from the community. It measured smoking cessation (defined as 7‐day point prevalence) at six months follow‐up.

Sertraline

One trial with six‐month follow‐up assessed sertraline (200 mg/day) for 11 weeks versus placebo in conjunction with six individual counselling sessions. All participants had a past history of major depression (Covey 2002).

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Moclobemide

Moclobemide was tested for smoking cessation in one placebo‐controlled trial, carried out in France (Berlin 1995). Participants were recruited using advertisements in community healthcare settings. Treatment with 400 mg/day began one week before quit day and continued for two months, reducing to 200 mg/day for a further month. No behavioural counselling was provided. Final follow‐up for smoking cessation (defined as prolonged abstinence) was at 12 months.

Selegiline

Five long‐term trials testing selegiline are included in this review, carried out in the USA (George 2003; Kahn 2012; Killen 2010; Weinberger 2010), and Israel (Biberman 2003). All studies recruited participants from the community.

Almost all studies delivered selegiline as a monotherapy compared to placebo, excluding Biberman 2003, which used a combination therapy of selegiline and nicotine patch compared to placebo.

Three studies used 10 mg/day of oral treatment (Biberman 2003; George 2003; Weinberger 2010), and two used 6 mg/day of patch treatment (Kahn 2012; Killen 2010). The nicotine patches also used in Biberman 2003 delivered 21 mg/day of nicotine for eight weeks. Three studies had treatment durations of nine weeks (George 2003; Kahn 2012; Weinberger 2010), one had a treatment duration of eight weeks (Killen 2010), and one continued therapy for 26 weeks (Biberman 2003). Three of the studies completed follow‐up at six months (George 2003; Kahn 2012; Killen 2010), and two continued follow‐up to 12 months (Biberman 2003; Weinberger 2010).

Lazabemide

Berlin 2002 is the only study of lazabemide included in this review. Due to its nature as a dose‐finding, exploratory study, its follow‐up period for smoking cessation was only eight weeks. Therefore, we only consider its safety data within this review.

The study was conducted in both France and Belgium; however, the method of participant recruitment is not reported. Participants were given either 50 mg lazabemide, 100 mg lazabemide or placebo. It was halted early due to liver toxicity observed in trials of the medication for other indications.

EVT302

Berlin 2012 is the only study of EVT302 included in this review. Its follow‐up for smoking cessation is only eight weeks, therefore we only consider its safety data within this review.

The study was conducted in Germany, with participants recruited through media advertisements. It compared EVT302 monotherapy (5 mg/day for 1 week preceding and 7 weeks following the target quit date) with placebo. It additionally compared EVT302 combination therapy with nicotine patch (21 mg/day for 7 weeks post‐target quit date) versus placebo EVT302 and nicotine patch.

Venlafaxine

Cinciripini 2005 is the only study of venflaxine included in this review. It recruited from the community and compared venlafaxine at a dose of up to 225 mg/day with placebo. All participants also received nicotine patches and nine brief individual counselling sessions; follow‐up was for 12 months.

Hypericum (St John’s wort)

Three studies of hypericum are included (Barnes 2006; Parsons 2009; Sood 2010), with Barnes 2006 newly included at this update. These studies took place in the USA (Sood 2010) and the UK (Barnes 2006; Parsons 2009). Participants were recruited from the community (Barnes 2006; Sood 2010) and stop‐smoking clinics (Parsons 2009).

All three studies reported prolonged abstinence at six months. Barnes 2006 compared 300 mg/day to 600 mg/day, starting one week prior to the target quit date and continuing for 12 weeks thereafter; Parsons 2009 compared 14 weeks of 900 mg/day St John's wort to placebo, starting two weeks prior to target quit date and continuing for 12 weeks thereafter; Sood 2010 compared 900 mg/day, 1800 mg/day, and placebo for 12 weeks.

S‐Adenosyl‐L‐Methionine (SAMe)

Sood 2012 is the only study of SAMe included in this review. It compared 1600 mg/day or 800 mg/day SAMe to placebo for eight weeks, with smoking cessation follow‐up at six months.

Excluded studies

For studies that were potentially relevant, but that we excluded, we have provided our reasons for exclusion in Characteristics of excluded studies. Reasons that records were excluded at full‐text stage for this update specifically, are also summarized in Figure 1.

As part of this update to the review, we have excluded studies investigating the use of antidepressants for smoking relapse prevention and harm reduction, as these studies are included in other reviews (Lindson‐Hawley 2016; Livingstone‐Banks 2019). Therefore, we have now excluded seven studies of relapse prevention (Covey 2007; Croghan 2007; Hall 2011; Hays 2001; Hays 2009; Hurt 2003; Killen 2006), and one of harm reduction (Hatsukami 2004), which were included in the previous update (Hughes 2014).

We identified the following three ongoing studies as part of our search which are likely to be relevant for inclusion when complete.

NCT03326128: compares two high doses of bupropion (300 mg/day to 450 mg/day, starting 4 weeks prior to and following target quit date).

NCT03342027: a factorial trial comparing bupropion to placebo, as well as an eight‐session tailored behavioural intervention.

Zawertailo 2018: compares bupropion (150 mg/day for the first 3 days, then twice daily for the remainder of the 12 weeks, starting 7 days prior to target quit day) and varenicline (0.5 mg once daily for first 3 days, then 0.5 mg twice daily for next 4 days, then 1 mg twice daily for the remainder of the 12 weeks, starting 7 days prior to target quit day).

Further details of these ongoing studies are summarized in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, we judged 12 studies to be at low risk of bias (low risk of bias across all domains), 28 at high risk of bias (high risk of bias in at least 1 domain), and the remaining 75 at unclear risk of bias. Reasons for the judgements made below are detailed in the Characteristics of included studies table, and a summary illustration of the 'Risk of bias' profile across studies is shown in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We assessed selection bias through investigating methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment for each study. We rated 46 studies at low risk for random sequence generation, 68 at unclear risk and one at high risk (Moreno‐Coutino 2015). We judged 31 studies to be at low risk for allocation concealment, 79 at unclear risk and five at high risk. When assessing both random sequence generation and allocation concealment, we assessed studies to be at unclear risk where there was insufficient methodological information available to be sure whether adequate measures had been taken to avoid selection bias.

Blinding

We assessed any risk of bias linked to blinding as one domain. However, we took into account both performance and detection bias when making this judgement. We judged 32 studies to be at low risk of bias for this domain, 64 at unclear risk and 19 at high risk. Where studies stated that they were "double‐blind" only, with no explicit clarification of who was blinded, we judged this to be unclear risk.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged studies to be at a low risk of attrition bias where the numbers of participants lost to follow‐up were clearly reported and the overall number lost to follow‐up was not more than 50%, and the difference in loss to follow‐up between groups was no greater than 20%. This is in accordance with 'Risk of bias' guidance produced by Cochrane Tobacco Addiction for assessing smoking cessation studies. We judged 69 of the studies to be at low risk of bias, 34 at unclear risk and 12 at high risk.

Other potential sources of bias

We found three studies with other sources of potential bias beyond those domains detailed previously. Siddiqi 2013 demonstrated substantial heterogeneity of programme effects across the different clusters of their cluster‐RCT. Twenty per cent of participants in the control arm smoked only hookah (no cigarettes) compared with 4% in the intervention arm. We judged that this put the study at high risk of bias. Weiner 2012 details that there was insufficient study drug available to meet demand. It is unclear how this was dealt with and whether it is accounted for in the dropouts reported. We judged this to be an unclear risk of bias. Finally, Zincir 2013 details that there were no adverse events recorded during their study. This seems highly unlikely according to the common definition of adverse events, and there is no detail given of how adverse events were measured in the study. We have therefore judged this to put the study at high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. Bupropion compared to placebo/no pharmacotherapy control for smoking cessation.

| Bupropion compared to placebo/control for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Population: people who smoke Setting: any; studies conducted in Asia, Australasia, Europe, USA Intervention: bupropion Comparison: placebo/control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo/control | Risk with bupropion | |||||

| Smoking cessation (at least six months follow‐up) | Study population | RR 1.64 (1.52 to 1.77) | 17,866 (46 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ||

| 11 per 100 | 18 per 100 (17 to 20) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 1.16 (0.90 to 1.48) | 10,625 (21 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | ||

| 2 per 100 | 3 per 100 (2 to 3) | |||||

| Dropouts due to adverse events of the drug | Study population | RR 1.37 (1.21 to 1.56) | 12,340 (25 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | ||

| 7 per 100 | 9 per 100 (8 to 10) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Confidence interval encompasses no difference as well as clinically significant increase. Total number of events less than 300.

Summary of findings 2. Bupropion plus NRT compared to NRT alone for smoking cessation.

| Bupropion plus NRT compared to NRT alone for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Population: people who smoke Setting: any; studies conducted in UK, USA Intervention: bupropion and NRT Comparison: NRT alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with NRT alone | Risk with bupropion and NRT | |||||

| Smoking cessation (at least six months follow‐up) | Study population | RR 1.19 (0.94 to 1.51) | 3487 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | ||

| 19 per 100 | 22 per 100 (17 to 28) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 1.52 (0.26 to 8.89) | 607 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d | ||

| 1 per 100 | 1 per 100 (0 to 6) | |||||

| Dropouts due to adverse events of the drug | Study population | RR 1.67 (0.95 to 2.92) | 538 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | ||

| 7 per 100 | 11 per 100 (6 to 19) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to inconsistency. Unexplained statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 52%). bDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Confidence interval encompasses no difference as well as clinically significant benefit. cDowngraded one level due to risk of bias. One of the three included studies judged to be at high risk of bias. Removing this study reduced the point estimate to 1.00. dDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. Fewer than 100 events.

Summary of findings 3. Bupropion plus varenicline compared to varenicline alone for smoking cessation.

| Bupropion plus varenicline compared to varenicline alone for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Population: people who smoke Setting: any; studies conducted in USA Intervention: bupropion and varenicline Comparison: varenicline alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with varenicline alone | Risk with bupropion and varenicline | |||||

| Smoking cessation (at least six months follow‐up) | Study population | RR 1.21 (0.95 to 1.55) | 1057 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | ||

| 21 per 100 | 26 per 100 (20 to 33) | |||||

| Serious adverse events | Study population | RR 1.23 (0.63 to 2.42) | 1268 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ||

| 2 per 100 | 3 per 100 (1 to 6) | |||||

| Dropouts due to adverse events of the drug | Study population | RR 0.80 (0.45 to 1.45) | 1230 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | ||

| 4 per 100 | 3 per 100 (2 to 6) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to imprecision. Fewer than 300 events overall. Confidence intervals encompass clinically significant benefit as well as no difference. bDowngraded two levels due to imprecision. Fewer than 100 events overall. Confidence intervals encompass clinically significant harm as well as clinically significant benefit.

Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control

Smoking cessation

There was evidence to suggest that bupropion was effective when compared to placebo or a non‐pharmacotherapeutic control to assist smoking cessation. Our meta‐analysis included 46 trials in which bupropion was the sole pharmacotherapy, with 17,866 participants: pooled risk ratio (RR) 1.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.52 to 1.77; I2 = 15%; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Table 1). The results were not sensitive to the exclusion of studies judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias overall. We excluded one cluster‐RCT of bupropion versus no pharmacotherapy from our meta‐analysis due to substantial heterogeneity of programme effects across clusters. This trial detected no evidence of a difference between bupropion and no pharmacotherapy (both groups received behavioural support) for smoking cessation at any follow‐up point (adjusted RR at 6‐month follow‐up: 1.1, 95% CI 0.5 to 2.3; 1299 participants) (Siddiqi 2013). Sensitivity analyses excluding studies with industry support did not indicate that our findings were sensitive to the inclusion of these studies (see Table 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 1: Smoking cessation

1. Sensitivity analyses excluding industry‐supported studies.

| Comparison and outcome | RR and CI excluding industry funded studies | RR and CI excluding studies with funding or medication provided by industry |

| Analysis 1.1 | 1.49 (1.33 to 1.66); studies = 26 | 1.48 (1.26 to 1.74); studies = 14 |

| Analysis 1.4 | 1.24 (1.14 to 1.35); studies = 9 | 1.24 (1.09 to 1.41); studies = 7 |

| Analysis 1.5 | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.21); studies = 11 | 0.88 (0.61 to 1.26); studies = 10 |

| Analysis 1.6 | 1.19 (0.72 to 1.94); studies = 4 | 1.19 (0.72 to 1.94); studies = 4 |

| Analysis 1.7 | 2.04 (0.23 to 17.84); studies = 7 | 2.61 (0.11 to 60.51); studies = 6 |

| Analysis 1.8 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 1.9 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 1.10 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 1.11 | 1.51 (0.44 to 5.27); studies = 6 | 1.51 (0.44 to 5.27); studies = 6 |

| Analysis 1.12 | 2.08 (0.93 to 4.64); studies = 4 | 2.27 (0.46 to 11.17); studies = 2 |

| Analysis 1.13 | 1.85 (1.55 to 2.20); studies = 11 | 1.85 (1.55 to 2.20); studies = 7 |

| Analysis 1.14 | 1.32 (0.98 to 1.77); studies = 11 | 1.11 (0.77 to 1.58); studies = 8 |

| Analysis 2.1 | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.32); studies = 11 | 0.78 (0.46 to 1.32); studies = 4 |

| Analysis 2.2 | 1.21 (1.02 to 1.43); studies = 2 | 1.24 (0.98 to 1.56); studies = 1 |

| Analysis 2.3 | 2.06 (0.20 to 21.67); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 2.4 | 2.93 (0.12 to 72.31); studies = 1 | 2.93 (0.12 to 72.31); studies = 1 |

| Analysis 2.5 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 2.6 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 2.7 | 0.68 (0.12 to 3.98); studies = 1 | 0.68 (0.12 to 3.98); studies = 1 |

| Analysis 2.10 | 1.04 (0.16 to 6.83); studies = 1 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 2.8 | 1.26 (0.60 to 2.65); studies = 1 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 2.9 | 1.62 (0.72 to 3.65); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.1 | 1.14 (0.85 to 1.51); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.2 | 1.05 (0.98 to 1.12); studies = 3 | 1.80 (0.53 to 6.16); studies = 1 |

| Analysis 3.3 | 1.31 (0.60 to 2.84); studies = 3 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.4 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.30); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.5 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.6 | 0.34 (0.01 to 8.27); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.7 | 0.34 (0.04 to 3.27); studies = 2 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.8 | Not estimable | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.9 | 0.34 (0.01 to 8.40); studies = 1 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.12 | 0.72 (0.37 to 1.40); studies = 4 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.10 | 1.49 (0.95 to 2.33); studies = 1 | Not estimable |

| Analysis 3.11 | 1.48 (1.15 to 1.89) | Not estimable |

CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio

We found no evidence suggesting that the effect of bupropion on smoking cessation depended upon the level of behavioural support offered to people stopping smoking. Three trials directly compared bupropion and placebo in factorial designs varying the behavioural support. There was no evidence from any of the three trials that the efficacy of bupropion differed between the lower and higher levels of behavioural support (Hall 2002; McCarthy 2008), or by the type of counselling approach used (Schmitz 2007). We also carried out a between‐study subgroup analysis of the possible interaction with behavioural support. We did this by classifying studies into low and high intensities of behavioural support (further split into delivery to a group or to individuals), using the criteria set in the Cochrane Review of NRT versus control (Hartmann‐Boyce 2018). Low‐intensity support consisted of less than 30 minutes at the initial consultation, with no more than two further assessment and reinforcement visits. Only one small trial met this criteria (Myles 2004). We found no evidence of a difference between subgroups (I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 2: Smoking cessation ‐ subgroup by level of behavioural support

One trial directly compared bupropion and placebo in a cohort of participants with mental health disorders to a cohort without (Anthenelli 2016). There was no evidence indicating that the effect of bupropion depended upon whether people had or did not have a psychiatric disorder. We also carried out a between studies subgroup analysis to assess the potential interaction between cessation rates and mental health disorders. We did this by pooling studies (or subgroups of studies) into groups depending upon whether the participants were recruited specifically because they had a mental health disorder or they represented the general population (including some studies that excluded people with current mental health disorders). Some of these groups included people with serious mental health disorders, such as people with schizophrenia (Evins 2001; Evins 2005; George 2002), or other disorders including post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Hertzberg 2001), and a mix of mental health disorders (Anthenelli 2016). We found no evidence of a differential effect of bupropion on cessation between subgroups (Analysis 1.3; I2 = 15%).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 3: Smoking cessation ‐ subgroup by mental health disorders

Depression

Four studies comparing bupropion to placebo/control analysed whether there was any interaction between depression and smoking quit rates (Anthenelli 2016 (analysis reported in West 2018); Aubin 2004; Cinciripini 2018; Kalman 2011). We did not find any evidence of this (Table 5).

2. Depression as a moderator of the relationship between antidepressants and smoking cessation.

| Study ID | Antidepressant | Direction of relationship | Evidence for interaction |

| Anthenelli 2016 | Bupropion | None | "Varenicline, bupropion and NRT were all effective in smokers with mental health problems (assessed with a number of variables, e.g. diagnostic history, HADS, use of psychotropic medication), and their relative efficacy was similar to that in smokers without a psychiatric history." |

| Aubin 2004 | Bupropion | None | "A similar subgroup analysis performed according to previous history of depression (evaluated by the MINI questionnaire) also failed to reveal an interaction with bupropion treatment." |

| Aveyard 2008 | Nortriptyline | None | "Participants randomised to nortriptyline plus nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation experienced less depression (OR 0.15) and anxiety early in the quit attempt when the risk of return to smoking is at its highest than those randomised to placebo plus nicotine replacement therapy. Contrary to expectations, no evidence was found that this led to greater abstinence." |

| Cinciripini 2018 | Bupropion | None | "Several measures failed to demonstrate significant effects as a function of time, treatment, or the interaction of treatment and time. For example, CES‐D scales including Depressive Affect, Interpersonal Relations, Positive Affect, and Somatic Symptoms, failed to demonstrate any effects of treatment or any treatment by time interactions." |

| Da Costa 2002 | Nortriptyline | Negative | "The best results were obtained with educational intervention, in those patients having no personal history of depression, who received the active drug. A negative history of depression was, however, the most important factor for the success of the treatment." |

| George 2003 | Selegiline | None (history), negative (current) | “There was no significant influence of a past history of major depression on smoking cessation outcomes (B = ‐0.49, SE = 0.90, Wald Statistic = 0.29, df = 1, p = .59), and when past history of major depression was entered into the logistic regression model as a covariate, it did not predict treatment failure with selegiline study medication (medication past history of depression status interaction: B = ‐0.02, SE = 1.03, Wald statistic = 0.00, df = 1, p = .98)." and "Furthermore, bivariate logistic regression analysis confirmed that having depressive symptoms at baseline negatively predicted smoking cessation outcomes with SEL on this continuous abstinence measure (B = 18.9, SE = 0.58, Wald statistic = 1048.9, df = 1, P < .01)." |

| Hall 2002 | Bupropion, nortripyline | Positive (for bupropion) | “There were higher abstinence rates for bupropion than nortriptyline for participants with a history of depressive disorder" |

| Kahn 2012 | Selegiline | None | "At the final HAM‐D assessment, the selegiline group (n = 90) reported a mean increase of 0.41 points and the placebo group (n = 85) reported a mean increase of 0.21 points. The difference between treatment groups was not statistically significant (t test, p = .65)." |

| Kalman 2011 | Bupropion | None | “Interaction effects between medication and tobacco dependence and medication and depressive symptoms were also nonsignificant.” |

| Killen 2000 | Paroxetine | None | "A stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association of abstinence at Week 26 with the variables [including depression scores] listed in Table 1. None of these variables were prospectively associated with abstinence." |

| Saules 2004 | Fluoxetine | None | “Examination of pre‐specified subgroups (i.e., gender, race, and history of major depressive disorder) did not reveal significant differences in smoking cessation by group” |

| Spring 2007 | Fluoxetine | None | Fluoxetine initially enhanced cessation for smokers with a history of major depression (P = .02) but subsequently impaired cessation regardless of depressive history. |

| Stapleton 2013 | Bupropion | Positive | “There was some evidence that the relative effectiveness of bupropion and NRT differed according to depression (χ2 = 2.86, P = 0.091), with bupropion appearing more beneficial than NRT in those with a history of depression (29.8 versus 18.5%)." |

| Wagena 2005 | Bupropion, nortriptyline | Positive (for bupropion) | “Results indicated that bupropion SR [sustained release] treatment was efficacious in helping smokers who were classified as depressed in achieving prolonged abstinence from smoking throughout the 26‐week period. The number of depressed participants from the nortriptyline‐treated group was considered too low to study this relationship." |

CES‐D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; df: degrees of freedom; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale; HAM‐D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MINI: Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; OR: odds ratio; SE: standard error

Safety

There was evidence to suggest that taking bupropion increased the incidence of adverse events (AEs) relative to placebo or non‐pharmacotherapeutic control (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.18; 19 studies, 10,893 participants; Analysis 1.4). However, a moderate degree of heterogeneity was detected between studies (I2 = 63%). Meta‐analysis of 21 studies did not provide clear evidence that the use of bupropion increased the likelihood of serious adverse events (SAEs) (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.48; I2 = 0%; 21 studies, 10,625 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Table 1), however the CIs encompassed both no difference as well as a clinically significant increase.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 4: Adverse events

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 5: Serious adverse events

There was also evidence to suggest bupropion increased the likelihood of developing psychiatric AEs. We meta‐analysed six studies (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.36; 6 studies, 4439 participants; Analysis 1.6). This effect is largely driven by Anthenelli 2016 (with an overall weighting of 96.9%), however as we judged this study to be at low risk of bias, and the effects are consistent with those detected by the other studies included in the analysis (I2 = 15%), this is not deemed to be problematic.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 6: Psychiatric adverse events

There was insufficient evidence to determine whether bupropion use was associated with the likelihood of seizures (RR 2.93, 95% CI 0.64 to 13.37; I2 = 0%; 13 studies, 7344 participants; Analysis 1.7), risk of overdose (RR 2.15, 95% CI 0.23 to 19.86; I2 = 0%; 5 studies, 5585 participants; Analysis 1.8), suicide attempts (RR 1.62, 95% CI 0.29 to 8.92; I2 = 0%; 10 studies, 6484 participants; Analysis 1.9), risk of death by suicide (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.01 to 8.26; I2 = n/a; 14 studies, 8822 participants; Analysis 1.10), or all‐cause mortality risk (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.87; I2 = 0%; 21 studies, 11,403 participants; Analysis 1.11). In all cases the number of events reported were very low, which resulted in substantial imprecision and CIs encompassing both clinically significant benefit and harm.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 7: Seizures

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 8: Overdoses

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 9: Suicide attempts

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 10: Death by suicide

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 11: All‐cause mortality

However, there was evidence that those randomized to receive bupropion were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety (RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.67; I2 = 40%; 11 studies, 7406 participants; Analysis 1.12) and insomnia (RR 1.78, 95% CI 1.62 to 1.96; I2 = 12%; 22 studies, 11,077 participants; Analysis 1.13) at follow‐up.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 12: Anxiety

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 13: Insomnia

Tolerability

There was evidence that the risk of dropout due to AEs of the drug was higher in groups receiving bupropion relative to placebo or no pharmaceutical treatment (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.56; I2 = 19%; 25 studies, 12,340 participants; high certainty evidence; Analysis 1.14; Table 1). Our point estimate suggests that participants taking bupropion had a 21% to 56% increased risk of dropping out relative to control.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Bupropion versus placebo/no pharmacotherapy control, Outcome 14: Dropouts due to drug

We carried out sensitivity analyses (not shown) for all of the above safety and tolerability analyses, removing studies at overall high risk of bias, where this was relevant. In no cases did this change the interpretation of the effect. Additional sensitivity analyses, excluding studies with industry support, did not indicate that our findings were sensitive to the inclusion of these studies (see Table 4).

Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone

Smoking cessation

There was moderate statistical heterogeneity in the results of 12 studies comparing bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) to NRT alone for smoking cessation (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.51; I2 = 52%; 12 studies, 3487 participants; low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.1; Table 2). The analysis thus found no clear evidence of a benefit of using bupropion plus NRT over using NRT alone. Nine of the 12 studies used nicotine patch, but two studies provided participants with nicotine lozenge (Piper 2009; Smith 2009), and one offered a choice of NRT (Stapleton 2013). However, splitting the analysis into these subgroups did not explain the heterogeneity detected (I2 = 0% for subgroup differences), nor did the exclusion of studies that did not use a bupropion placebo in the control arm (Smith 2009; Stapleton 2013). Removing the three studies deemed to be at an overall high risk of bias did not change the interpretation of the pooled effect estimate (Rose 2013; Smith 2009; Stapleton 2013). Sensitivity analyses excluding studies with industry support did not indicate that our findings were sensitive to the inclusion of these studies (see Table 4). Although the direction of the effect estimate changed when studies funded by the pharmaceutical industry, or where the medication was supplied by the pharmaceutical industry, were excluded; 95% CIs still encompassed evidence of benefit as well as harm.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 1: Smoking cessation

Depression

None of the relevant included studies investigated depression as a moderator of smoking quit rates.

Safety

There was evidence to indicate an increased risk of AEs when using combination bupropion and NRT relative to taking NRT alone (RR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.43; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 313 participants; Analysis 2.2); however the number of events was low (n = 192), and when one study at high risk of bias was removed the outcome become more imprecise and the CI spanned one (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.56). There was insufficient evidence for the other safety outcomes we analysed for this comparison (SAEs, seizures, suicide attempts, death by suicide, all‐cause mortality). Very few studies had relevant data, and those that did recorded few events. In the case of the SAEs outcome, the removal of one study deemed to be at high risk of bias changed the effect estimate from RR = 1.52 (95% CI 0.26 to 8.89; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 607 participants; very low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.3; Table 2) to RR = 1.00 (95% CI 0.06 to 15.83; I2 = n/a; 2 studies, 538 participants). Although this did not change the clinical interpretation of the result it does demonstrate that the effect estimate was highly dependent on this potentially biased study.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 2: Adverse events

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 3: Serious adverse events

There was some evidence that bupropion plus NRT led to increased reporting of insomnia in comparison to NRT alone (RR 1.55, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.93; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 556 participants; Analysis 2.8); however there was no clear evidence of an increase in anxiety in the bupropion plus NRT groups (RR 1.58, 95% CI 0.97 to 2.56; I2 = 47%; 3 studies, 1218 participants; Analysis 2.9). In both cases the results were based on a small number of studies and event rates were low (< 300).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 8: Insomnia

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 9: Anxiety

Tolerability

Only two studies measured dropout due to AEs of the drug, providing insufficient information to draw conclusions and an imprecise pooled effect estimate (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.95 to 2.92; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 538 participants; low certainty evidence; Analysis 2.10; Table 2).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Bupropion plus nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) versus NRT alone, Outcome 10: Dropouts due to drug

Removing studies judged to be at high risk of bias from safety and tolerability analyses did not affect the interpretation of these effects, and sensitivity analyses, excluding studies with industry support, did not indicate that our findings were sensitive to the inclusion of these studies (see Table 4).

Bupropion plus varenicline versus varenicline alone

Smoking cessation