Abstract

Purpose: We investigated the relation between adversities in early adolescence and risk of a depressive phenotype in adulthood, and whether stress in adulthood modified these associations.

Methods: A total of 1138 men who have sex with men (MSM) participated in a Multicenter AIDS Cohort substudy in which they reported on adversities in early adolescence. Poisson regression estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) for associations between adversities and a depressive phenotype in adulthood. Stratified analyses examined the effects of stress in the last year on the depressive phenotype.

Results: In adjusted models, men who were verbally insulted; threatened by physical violence; had an object thrown at them; or punched, kicked, or beaten were at higher risk of having a depressive phenotype in adulthood (for ≥1 time per month vs. never, PR = 1.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.15–1.96; PR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.45–2.34; PR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.51–2.66; or PR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.35–2.34, respectively.) Being threatened with a weapon approached statistical significance (PR = 1.89, 95% CI = 0.96–3.72). Although higher stress was associated with depression overall, early adolescent victimization was only associated with depression among MSM not reporting high levels of stress in the last year (for ≥1 time per month vs. never, PR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.09–2.59; PR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.40–3.17; PR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.24–4.03; PR = 1.98, 95% CI = 1.22–3.22, respectively).

Conclusion: The attenuation of relationships between adversities and depression among men reporting high stress may suggest that adult stress overshadows long-term effects of early adolescent victimization on adult depression. Victimization in early adolescence may increase the risk of sustained depressive symptoms in mid- to later life, reinforcing the need for preventive strategies.

Keywords: depression, early adolescence, HIV, MSM, stress victimization

Introduction

Men who have sex with men (MSM) experience notable health disparities compared with men who have only opposite sex partners, including a fivefold higher risk of depressive symptoms.1 Given the negative effects of stigma on the health of sexual minority individuals,2–5 the heightened risk of depressive symptoms may be partially attributable to stress related to stigmatization.5,6

Experiences of stigma, discrimination, sexual orientation concealment, and internalized homophobia can lead to internalized gay ageism—the joint internalization of ageism and homophobia—exacerbating depression risk in later life.7 However, questions remain: what kinds of negative experiences in an individual's lifecourse have an impact on depression risk in older adulthood? How might the association between adverse events earlier in life differ depending on experiences of stress later in life?

For sexual minority individuals, these are important questions as they experience stress and victimization disproportionately throughout the lifecourse.3,8 Childhood victimization can include sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and neglect. With median prevalence of victimization ranging from 21% to 49%,9 many LGBT individuals have experienced childhood adversities, which may put them at higher risk for mental disorders in adulthood.10–13

In previous work from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), high scores on a young adolescent victimization index were cross-sectionally associated with depressive symptoms in adulthood.14 However, such single time point assessments in adulthood may not reflect longer term risk of clinically significant depression and could be prone to recall bias in those currently experiencing depressive symptoms.14 Furthermore, previous studies among sexual minority individuals have not investigated specific types of violence to understand whether certain acts are more harmful. Adverse events in childhood and adolescence alter social-emotional regulation through increasing sensitivity to everyday life events,15 raising the question of whether sensitization from victimization in young adolescence may modify the effect of adult stress to increase the risk of mental health problems. Evidence supports the idea that victimization up to age 18 may predict distress in early adulthood.16 Understanding the impact of young adolescent experiences of victimization on later life mental health and its relationship with stress could form the basis for identifying individuals at risk, especially among aging MSM who are living with HIV or at risk of HIV infection.

In this study, we examined five specific types of self-reported victimization in early adolescence in relation to long-term depressive symptoms in adulthood. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine young adolescent victimization and the role of adult stress in the last year in relation to depressive symptoms over time among HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM.

Methods

Study population

The MACS is a prospective cohort of HIV infection among MSM in Baltimore, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh. Enrolling MSM since 1984, it is one of the largest and longest running studies of the history of HIV/AIDS in the United States. Participants attend semi-annual study visits that include the administration of standardized questionnaires, collection of biospecimens for concurrent testing and repository storage, and physical examination.17–19 The study was approved by ethical review boards at Johns Hopkins University, the University of Pittsburgh, Northwestern University, and the University of California Los Angeles. Each participant provided written informed consent.

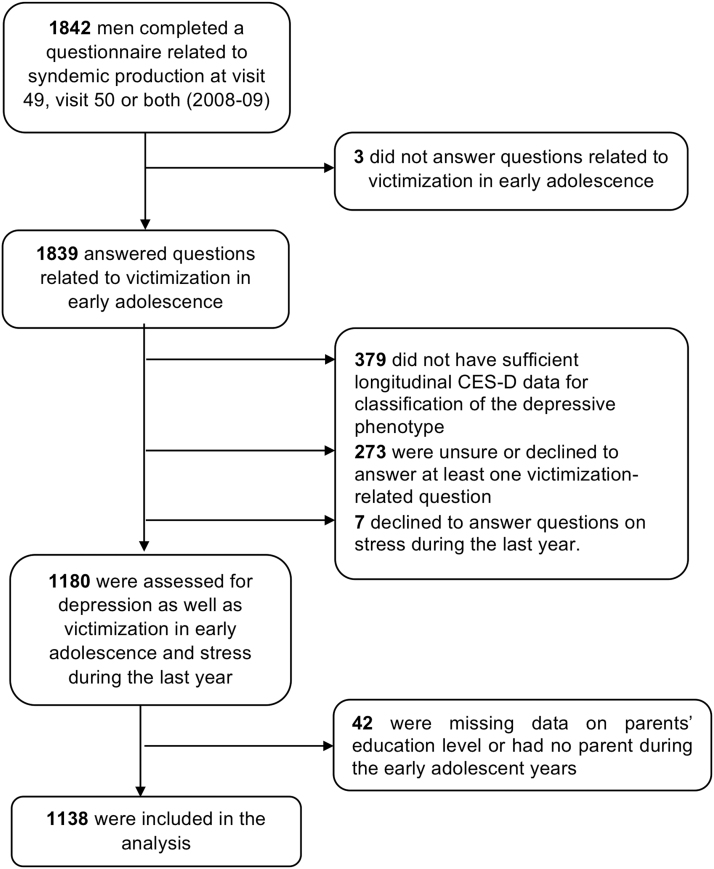

A total of 1842 MACS participants completed a Methamphetamine Substudy questionnaire in at least one of two consecutive study visits in 2008–2009.14 This substudy included the completion of a ∼30- to 45-minute survey examining the long-term health effects of methamphetamine use and asking about life events that could affect men's health. A subset of participants had sufficient longitudinal assessment of Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scores, and clinical and behavioral factors to allow for the identification of depressive phenotypes (N = 1460). We further excluded men if they were unsure if they were abused (n = 210); declined to answer one or more young adolescent victimization-related questions (n = 63); declined to answer any questions related to adult stress in the last year (n = 7); or could not recall or declined to provide information on parents' education level or had no parent during ages 12–14 years (n = 42; Figure 1). We considered information on parental education to be an important proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood, which was related to onset of depression in older adulthood.20

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram of Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study participants included in the analysis. CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression.

Outcome: depressive phenotype

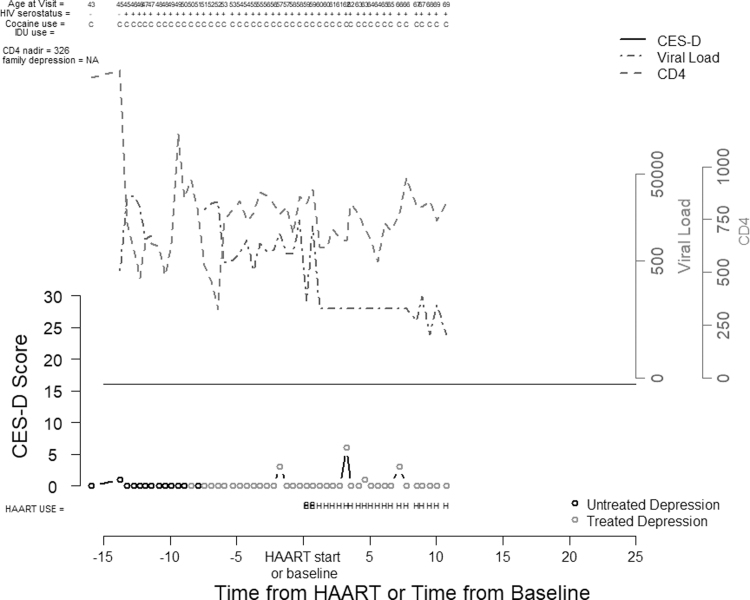

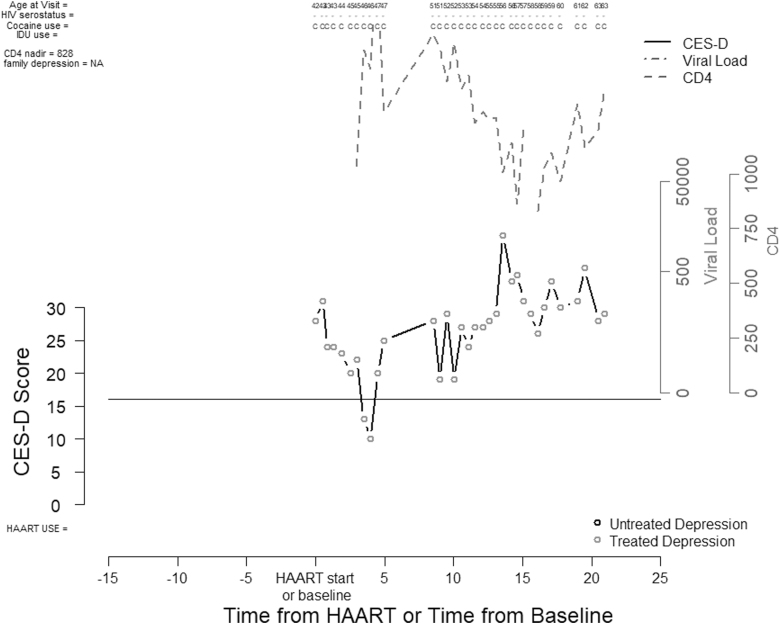

We examined long-term patterns of depressive symptoms to identify men with a depressive phenotype. The outcome was defined based on a novel clinical expertise-based classification system that used both CES-D scale scores and other MACS data.21 The classification system has been used in the MACS as a standard on which optimal metrics have been defined for using longitudinal CES-D data.21 In brief, MACS participants with at least 10 CES-D scores (over at least 5 years in adulthood) were classified as depressed or nondepressed by a clinical psychiatrist and two investigators using graphical displays of symptom patterns in conjunction with available relevant clinical (e.g., age, CD4 cell count, virologic suppression, and medication use) and behavioral data (e.g., drug use). Figures 2 and 3 show examples of a nondepressed versus depressed phenotype.

FIG. 2.

Example of CES-D scale scores and other clinical and behavioral plots used to classify a participant without the depressive phenotype. HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; IDU, injection drug use; NA, not available.

FIG. 3.

Example of CES-D scale scores and other clinical and behavioral plots used to classify a participant with the depressive phenotype.

Exposure: victimization in early adolescence

Young adolescent victimization was measured by five questions in the Methamphetamine Substudy, including if the participant was (1) verbally insulted; (2) threatened by physical violence; (3) had an object thrown at him; (4) punched, kicked, or beaten; or (5) threatened with a knife, gun, or another weapon.22 Questions referred to experiences occurring when the participant was 12–14 years old. This time period was chosen because (1) around 12–13 years is the time when consciousness about the direction of sexual identity begins,23 (2) youth who are 12–14 years of age have the highest rates of victimization in the United States,24 and (3) children who report same-sex attraction already report higher levels of victimization than their peers by this age.25 Victimization in early adolescence was categorized as frequent (≥1 per month); less frequent (<1 per month); and none.

To assess the repeatability of the victimization survey, we compared the responses at the two visits in which the Methamphetamine Substudy data were collected among a subset of participants who completed the survey at both time points. We used responses from the earliest administration of the survey if data were collected on young adolescent victimization at multiple visits. In addition, to evaluate the potential impact of nonresponse on the study results, we compared the characteristics and prevalence of the depressive phenotype of respondents to that of nonrespondents. All analyses were performed in SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Figures were created in R, version 3.2.2 (The R Foundation).

Effect modifier: adult stress

Adult stress in the last year was measured using a 14-item stressful life event scale.14 This scale included items regarding the amount of perceived stress experienced in the last 12 months related to a variety of factors (such as transportation, education, crime and violence, money and finances, and the neighborhood environment). Response categories ranged from no stress to extreme stress on a 5-point scale (no, a little, some, a lot, and extreme stress) and were summed. Participants were considered to have high stress if they averaged more than a little stress across the 14 items, in line with cutoffs used in previous research conducted in the MACS.14

Other variables included in the analysis were as follows: age (continuous), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and other), MACS Cohort (before 2001, 2001 or after), MACS Center (Baltimore, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles), parents' education (≤ high school, junior college/trade school, college or above), participant's education (≤ high school, some college, college or above), income (<20,000, 20,000–59,999, ≥60,000), used marijuana since last visit (yes/no), ever used marijuana (yes/no), ever used poppers (yes/no), ever used crack cocaine (yes/no), ever used uppers (yes/no), ever used heroin or other opiates (yes/no), ever used ecstasy, XTC, X, or MDMA (yes/no); alcohol use (none, low/moderate, moderate/heavy, binge), HIV infection (yes/no), number of supportive people (0, 1, ≥2), and adult stress (yes/no).

Statistical methods

Using the Kruskal–Wallis test or chi-squared test as appropriate, we compared the sociodemographic characteristics of groups of men who reported frequent young adolescent victimization, less frequent victimization, and no victimization. We estimated prevalence ratios (PRs) to quantify associations between victimization and depressive phenotypes using Poisson regression models with robust variance. A separate Poisson regression model was constructed for each of the five questions related to victimization; the prevalence of depression in the group reporting frequent victimization and in the group reporting less frequent victimization was compared with the reference group (men who reported no victimization). When data were too sparse, for example, for “being threatened with a knife, gun, or another weapon,” models were not fit.

As the exposure of interest occurred in early adolescence before study entry, adjusted models included a minimal set of covariates that were fixed: age at first CES-D assessment, MACS study site, recruitment cohort, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and other, vs. non-Hispanic White), and parental education level (≤ high school or missing one or both parents, junior college or trade school, vs. college and above). Participant adult SES, educational attainment, and HIV serostatus were not included as they were considered potential mediators of the young adolescent victimization–depression relationship. Because of the risk of differential recall bias by current depression status, we conducted a sensitivity analysis that excluded men who scored ≥20 on the CES-D at the study visit in which they reported early adolescent victimization (n = 234).

Associations between young adolescent victimization and adult depressive phenotypes were also examined separately by adult stress level as represented by self-report of stress during the last year. Effect modification by the level of adult stress was tested by adding two interaction terms (frequent victimization × adult stress; less frequent victimization × adult stress) to each of the Poisson regression models. p-values for the interaction terms were calculated using likelihood ratio tests.

Results

Among 1138 participants included in the analysis, 82% (n = 930) reported any type of victimization in early adolescence and 61% (n = 694) reported at least two types of victimization. At the time of the substudy, 47% of the analytical sample were living with HIV. Compared with participants who reported not being victimized, those who reported victimization in early adolescence were more likely to be non-Hispanic White men and to have attained at least a college education. In contrast, educational attainment of parents was similar across victimization status. As shown in Table 1, there appeared to be a pattern of drug use, such that men who reported victimization in early adolescence tended to more often report use of marijuana since last visit, ever using poppers, and ever using uppers, compared with participants not reporting any victimization in early adolescence. For the 710 (62%) participants who completed the survey twice, agreement of responses ranged between 73% and 92%. Participants were more likely to report being verbally insulted (75% vs. 69%) and threatened by physical violence (55% vs. 47%) at the first survey administration.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Characteristics | Victimization in early adolescence |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 per month (n = 554) | <1 per month (n = 376) | Never (n = 208) | ||

| Age,a median (IQR), years | 51 (46–57) | 53 (47–60) | 53 (47–61) | <0.001 |

| HIV infection, n (%) | 280 (51) | 166 (44) | 97 (47) | 0.15 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 392 (71) | 248 (66) | 126 (61) | 0.002 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 94 (17) | 83 (22) | 66 (32) | |

| Hispanic | 60 (11) | 41 (11) | 15 (7) | |

| Other | 8 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | |

| Cohort, n (%) | ||||

| Pre-2001 | 340 (61) | 237 (63) | 132 (64) | 0.82 |

| 2001+ | 214 (39) | 139 (37) | 76 (37) | |

| MACS center, n (%) | ||||

| Baltimore | 145 (26) | 87 (23) | 78 (38) | 0.001 |

| Chicago | 100 (18) | 80 (21) | 47 (23) | |

| Pittsburgh | 121 (22) | 88 (23) | 39 (19) | |

| Los Angeles | 188 (34) | 121 (32) | 44 (21) | |

| Parents' education, n (%) | ||||

| High school and below | 285 (51) | 188 (50) | 118 (57) | 0.53 |

| Junior college (2 years) or trade school | 99 (18) | 72 (19) | 30 (14) | |

| College and above | 170 (31) | 116 (31) | 60 (29) | |

| Education,an (%) | ||||

| High school and below | 60 (12) | 41 (12) | 42 (22) | 0.002 |

| Some college | 129 (26) | 65 (20) | 35 (18) | |

| College and above | 313 (62) | 226 (68) | 116 (60) | |

| Income, n (%) | ||||

| <20,000 | 136 (26) | 87 (25) | 63 (33) | 0.18 |

| 20,000–59,999 | 207 (39) | 130 (37) | 60 (31) | |

| ≥60,000 | 184 (35) | 132 (38) | 68 (36) | |

| Used marijuana since last visit, n (%) | 174 (32) | 92 (25) | 41 (20) | 0.002 |

| Ever used marijuana, n (%) | 431 (78) | 278 (76) | 155 (75) | 0.56 |

| Ever used poppers, n (%) | 390 (71) | 246 (67) | 118 (57) | 0.002 |

| Ever used crack cocaine, n (%) | 305 (56) | 192 (53) | 99 (48) | 0.18 |

| Ever used uppers, n (%) | 199 (36) | 105 (29) | 58 (28) | 0.022 |

| Ever used heroin or other opiates, n (%) | 46 (8) | 30 (8) | 18 (9) | 0.98 |

| Ever used ecstasy, XTC, X, or MDMA, n (%) | 132 (24) | 78 (21) | 33 (16) | 0.06 |

| Drinking, n (%) | ||||

| None | 104 (19) | 58 (16) | 42 (21) | 0.69 |

| Low/moderate | 316 (58) | 220 (60) | 121 (60) | |

| Moderate/heavy | 86 (16) | 63 (17) | 26 (13) | |

| Binge | 37 (7) | 23 (6) | 14 (7) | |

| Number of people that can be counted on for support, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 31 (6) | 21 (6) | 12 (6) | 0.99 |

| 1 | 96 (18) | 58 (17) | 36 (18) | |

| ≥2 | 397 (76) | 267 (77) | 151 (76) | |

| Experienced stress during the last year, n (%) | 193 (35) | 90 (24) | 39 (19) | <0.001 |

All variables starting from (and including) education were determined at the visit when participants completed the methamphetamine substudy questionnaire.

IQR, interquartile range; MACS, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study; MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine which is also known as ecstasy, sometimes abbreviated as XTC and X.

Prevalence of depression

Overall, the depressive phenotype prevalence was higher among participants who reported experiencing young adolescent victimization compared with those who did not. Moreover, the depressive phenotype was more common among MSM who reported young adolescent victimization and experienced stress in adulthood compared with those who did not. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, among MSM who were verbally insulted ≥1 time per month in early adolescence, 31% had the depressive phenotype in later adulthood, compared with 21% who were not verbally insulted in early adolescence. This pattern was similar for the other young adolescent victimization exposures, but with approximately twofold or higher prevalence in the frequently victimized group compared with the not victimized group (for all exposures except being verbally insulted).

Adjusted associations

When adjusting for age at first CES-D assessment, MACS study site, recruitment cohort, race/ethnicity, and parental education level (Table 2, Model 2), we found associations between frequent victimization (≥1 time a month) and higher risk of depression, compared with MSM who reported never being victimized in early adolescence (adjusted PR = 1.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.15–1.96 for verbally insulted; adjusted PR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.45–2.34 for threatened by physical violence; adjusted PR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.51–2.66 for having an object thrown at him; adjusted PR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.35–2.34 for being punched, kicked, or beaten). Being threatened with a weapon approached being statistically significantly associated with the depressive phenotype (adjusted PR = 1.89, 95% CI = 0.96–3.72). With the exception of being verbally insulted, we found statistically significant associations between less frequent young adolescent victimization (<1 per month) and depression, compared with depression among MSM who reported never being victimized in early adolescence.

Table 2.

Bivariate and Adjusted Associations Between Victimization in Early Adolescence and the Depressive Phenotype During Adulthood

| Victimization in early adolescence | Model 1 (N = 1138) |

Model 2 (N = 1138) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95% CI) | p | PR (95% CI) | p | |

| Verbally insulted | ||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.10 (0.81–1.49) | 0.539 | 1.16 (0.86–1.56) | 0.345 |

| ≥1 time/month | 1.45 (1.11–1.90) | 0.007 | 1.50 (1.15–1.96) | 0.003 |

| Threatened by physical violence | ||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.34 (1.06–1.70) | 0.013 | 1.33 (1.06–1.68) | 0.015 |

| ≥1 time/month | 1.97 (1.55–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.45–2.34) | <0.001 |

| Had an object thrown at him | ||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.48 (1.20–1.83) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.16–1.76) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 time/month | 2.15 (1.64–2.83) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.51–2.66) | <0.001 |

| Punched, kicked, or beaten | ||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.46 (1.18–1.80) | <0.001 | 1.46 (1.19–1.80) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 time/month | 1.90 (1.45–2.51) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.35–2.34) | <0.001 |

| Threatened with a weapon | ||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| <1 time/month | 2.00 (1.51–2.65) | <0.001 | 1.73 (1.30–2.30) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 time/month | 2.28 (1.19–4.37) | 0.013 | 1.89 (0.96–3.72) | 0.067 |

Model 1 is a univariable Poisson regression model using a robust variance estimator.

Model 2 is adjusted for age at first CES-D assessment used in the depressive phenotype, race/ethnicity, parental education, cohort, and MACS study site.

CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression; CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

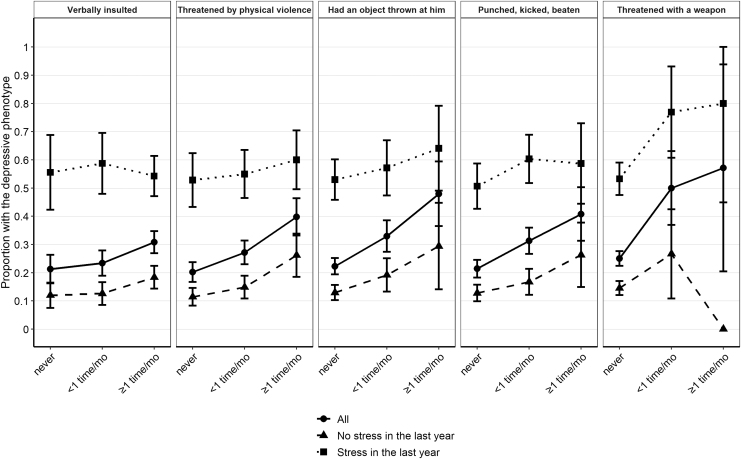

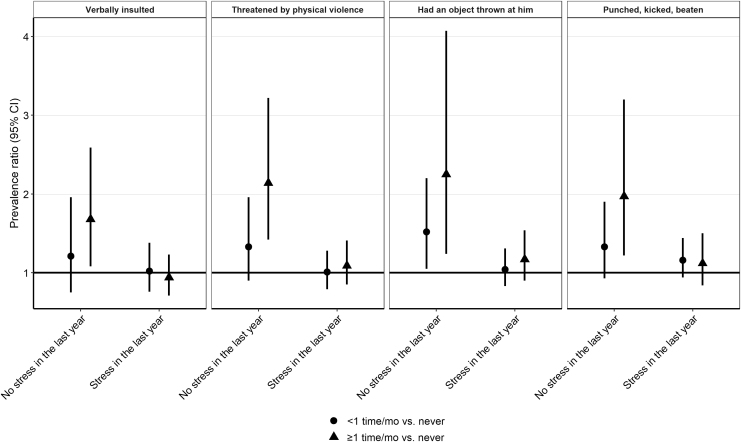

Associations stratified by adult stress

Although the prevalence of depression was higher among men with stress in the last year compared with men without stress in the last year as shown in Supplementary Table S1 (Fig. 4), Table 3 suggests that in analyses stratified by adult stress, stronger associations between victimization and depression were noted among participants not reporting stress. Table 3 and Figure 5 provide stratified adjusted analyses. Among men not reporting stress in the last year, the prevalence of a depressive phenotype was higher for MSM who reported being verbally insulted in early adolescence ≥1 time per month (adjusted PR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.09–2.59) compared with those who reported never having been verbally insulted in early adolescence. Similarly, among MSM not experiencing stress in the last year, being threatened by physical violence in early adolescence (adjusted PR = 2.11, 95% CI = 1.40–3.17); having an object thrown at him (adjusted PR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.24–4.03); and being punched, kicked, or beaten (adjusted PR = 1.98, 95% CI = 1.22–3.22) were associated with higher prevalence of the depressive phenotype. Among those who reported adult stress, these factors were not clearly related to depression and the associations were generally weaker in magnitude.

FIG. 4.

Prevalence and 95% CIs of the depressive phenotype by the frequency of victimization in early adolescence in the overall study population. The figure shows plots of the proportion of MSM with the depressive phenotype for each of the victimization indicators by their frequency. CIs, confidence intervals; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Table 3.

Association Between the Frequency of Victimization in Early Adolescence and the Prevalence of the Depressive Phenotype During Adulthood, Stratified by Stress Level During the Last Year

| Victimization in early adolescence | Experienced stress during the last year |

p Value for interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 816) |

Yes (n = 322) |

||||

| PR (95% CI) | p | PR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Verbally insulted | |||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | 0.15 | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.20 (0.74–1.95) | 0.449 | 1.04 (0.77–1.42) | 0.785 | |

| ≥1 time/month | 1.68 (1.09–2.59) | 0.018 | 0.96 (0.73–1.27) | 0.789 | |

| Threatened by physical violence | |||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | 0.04 | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.32 (0.90–1.93) | 0.161 | 1.02 (0.81–1.30) | 0.843 | |

| ≥1 time/month | 2.11 (1.40–3.17) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.87–1.44) | 0.376 | |

| Had an object thrown at him | |||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | 0.11 | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.52 (1.06–2.19) | 0.024 | 1.06 (0.85–1.33) | 0.602 | |

| ≥1 time/month | 2.24 (1.24–4.03) | 0.007 | 1.19 (0.91–1.57) | 0.211 | |

| Punched, kicked, or beaten | |||||

| Never | Ref | Ref | 0.22 | ||

| <1 time/month | 1.32 (0.92–1.89) | 0.125 | 1.18 (0.95–1.46) | 0.138 | |

| ≥1 time/month | 1.98 (1.22–3.22) | 0.006 | 1.14 (0.85–1.53) | 0.37 | |

All models were adjusted for age at first CES-D assessment used in the depressive phenotype, race/ethnicity, parental education level, cohort, and MACS study site.

FIG. 5.

Association between the frequency of victimization in early adolescence and the depressive phenotype during adulthood. The figure shows plots of the prevalence ratios displaying victimization for MSM with the depressive phenotype, stratified by stress in the last year.

Sensitivity analysis

As shown in Supplementary Table S2, among the subset of men scoring <20 on the CES-D at the MACS visit in which they reported on early adolescent victimization and who did not experience stress in the last year, associations remained generally consistent. However, the associations between being verbally insulted or punched, kicked, or beaten and depression became marginally significant. As shown in Supplementary Table S3, when stratifying by HIV serostatus, adjusted PRs were notably higher among HIV-negative versus HIV-positive MSM, although interaction terms testing differences by HIV serostatus were not statistically significant except for being punched, kicked, or beaten.

We also assessed the representativeness of our sample in comparison with the full cohort. Compared with responders, nonresponders were more likely to have a history of recreational drug use but were otherwise similar to responders.

Discussion

In this large study of MSM, we found that 82% of participants experienced one or more types of victimization in early adolescence. Being verbally insulted was the most prevalent type of adverse experience, reported by 77%. This is substantially higher than 1 year (28%) and lifetime (40%) prevalence estimates associated with “teasing or emotional bullying” in a representative sample of U.S. 10- to 13-year-olds.26 However, it echoes the prevalence of verbal harassment found among U.S. lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning high school students (85.2%).27 Given the stigma and emotional toll of early victimization, the observed prevalence in our study may even be an underestimate of the true burden of victimization if those victimized were less likely to respond to the survey.

The results suggested that all but one kind of young adolescent victimization—ranging from being verbally insulted to less common events—were significantly associated with the depressive phenotype in adulthood. The types of victimization were moderately correlated, illustrating that MSM who experience abuse often experience multiple forms of abuse. As expected, stress in the last year was related to higher levels of depression. Men reporting more frequent experiences of victimization appeared at higher risk of depression in adulthood, with associations primarily driven by MSM who perceived themselves as not stressed during the last year. It is possible that more immediate stressors may overshadow effects of earlier (less proximal) traumatic events on depression risk.

These findings are particularly important because discriminatory experiences, such as being insulted or threatened, are ∼3.5 times more likely among gay or bisexual individuals.4 Based on Meyer's minority stress theory, processes contributing to hostile and stressful social environments for sexual minority individuals include objective stressful events, expectations of such events, and internalization of negative societal attitudes.5 Stigma can lead to internalization of homophobia, which can lead to depression among sexual minority male youth.28 Adolescence is a sensitive developmental stage that may prime individuals for later risk of depression and anxiety.29 It is possible that bullying and abuse during this period are major factors explaining the associations with subsequent depressive symptoms for some sexual minority individuals.30

Although some studies have linked childhood or adolescent adversities to adult depression, the results are inconsistent.14,31 In a household probability sample of adult MSM, participants were asked about history of child abuse and history of anti-gay harassment occurring before the age of 16 years. MSM with a history of harassment were more likely to be distressed (defined as CES-D score 16–21) but were less likely to be depressed (CES-D score ≥22).31 Child abuse, however, was found to be a risk factor for depression but not distress in that study.31 Our previous work from the MACS showed that a summed index of young adolescent adversities was associated with higher risk of adult depressive symptoms at a single timepoint,14 but this could be attributed to recall bias by current depressive status. Furthermore, reports of depressive symptoms at a single timepoint are not necessarily indicative of long-term susceptibility to depression.

This study expands on previous research by differentiating types of abuse, which differ in severity and frequency of occurrence. Furthermore, our depressive phenotype corresponds to a summary of depressive symptom scores and indicators of depression over the duration of an individual's study participation (at least 5 years)—a novel outcome that incorporated clinical expertise and took advantage of data beyond CES-D scores.21 Finally, we were able to investigate whether the experience of adult stress in the last year modified the impact of young adolescent victimization on adult depressive symptoms.

Although we hypothesized that victimization in early adolescence might have a larger synergistic effect on depression among HIV-positive men, with the exception of being punched, kicked, or beaten, we did not find differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative men with respect to the impact of young adolescent adversities on long-term depression risk. Studies indicate that MSM may experience discrimination for multiple reasons including sexual minority status,32 possible HIV infection,33 and because of multiple health-related comorbidities that are more common among people with HIV (e.g., depression).34,35 Improved linkage to supportive services among HIV-positive men through their HIV care may mitigate any increased risk of depression resulting from young adolescent victimization. Alternatively, HIV-positive men in the MACS cohort are long-term survivors of HIV and may represent a more resilient group.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. We were reliant on the participants remembering victimization events that occurred in early adolescence. Although these are salient events likely to be remembered even after long periods, only 72% of study participants consistently recalled victimization experiences at two separate administrations of the survey, suggesting some discrepancy in recall that may have attenuated estimates of associations with the depressive symptom phenotype. This variability across repeated assessments could have resulted from survey fatigue; therefore, we used the first available report in our analyses to compensate for this possibility.

Several exclusions may have also affected our results. First, 14% of the sample was excluded because they reported that they were unsure of being abused. If these respondents were in fact more likely to have been abused, this may have potentially biased the strength of our associations toward the null. Likewise, our depressive phenotype measure required that a participant have data on the CES-D from at least 10 data points over time. If depressed individuals were less likely to show up as frequently for visits, this may also have caused us to include fewer depressed MACS participants. Our sample overall may not be representative of sexual minority men in the United States, given that they were sampled from the four MACS sites that are urban centers and do not represent the demographic characteristics of MSM in other parts of the country.

Depressive symptoms at the time of recall seemed to influence the recollection of events in early adolescence—we found that men reporting depressive symptoms at the time of the survey were more likely to recall abuse in early adolescence than participants without depressive symptoms. To evaluate the potential for differential recall to impact our results, we excluded these participants in a sensitivity analysis and found no substantive changes to the results. Nonresponse to the survey was also associated with higher prevalence of depressive phenotype and its predictors. To the degree that under- or overreporting of victimization is random, associations may be underestimates of the true association.

Future research

Further research is needed to investigate which factors can mitigate the negative effects of adverse events in early adolescence after they have occurred. If identified, such factors could be natural starting points to inform interventions to help MSM who are subsequently depressed. Of more immediate utility, surveys in adulthood of young adolescent experiences of victimization may serve as screening instruments to identify individuals at risk of long-term depression. Finally, further research should focus on whether the effects of early life traumatic events may be more pronounced within racial subgroups, among people experiencing certain types of stress, and whether these experiences can be compounded by discrimination.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that among sexual minority men, adverse events in early adolescence were related to sustained depression later in life. When comparing men who reported adult stress in the last year with those who did not, the association between early adolescent victimization and depression persisted among MSM not reporting high levels of stress. One interpretation is that early adversity is overshadowed by recent stressful events but may play an important role in priming MSM for depression in later life.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the collaborators, staff, and participants of the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS). The authors also wish to thank the Center for AIDS Research at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Data in this article were collected by MACS with centers in Baltimore (U01-AI35042): The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Joseph B. Margolick (PI), Jay Bream, Todd Brown, Adrian Dobs, Michelle Estrella, W. David Hardy, Lisette Johnson-Hill, Sean Leng, Anne Monroe, Cynthia Munro, Michael W. Plankey, Wendy Post, Ned Sacktor, Jennifer Schrack, Chloe Thio; Chicago (U01-AI35039): Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and Cook County Bureau of Health Services: Steven M. Wolinsky (PI), Sheila Badri, Dana Gabuzda, Frank J. Palella, Jr., Sudhir Penugonda, John P. Phair, Susheel Reddy, Matthew Stephens, Linda Teplin; Los Angeles (U01-AI35040): University of California, UCLA Schools of Public Health and Medicine: Roger Detels (PI), Otoniel Martínez-Maza (PI), Peter Anton, Robert Bolan, Elizabeth Breen, Anthony Butch, Shehnaz Hussain, Beth Jamieson, John Oishi, Harry Vinters, Dorothy Wiley, Mallory Witt, Otto Yang, Stephen Young, Zuo Feng Zhang; Pittsburgh (U01-AI35041): University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health: Charles R. Rinaldo (PI), James T. Becker, Phalguni Gupta, Kenneth Ho, Lawrence A. Kingsley, Susan Koletar, Jeremy J. Martinson, John W. Mellors, Anthony J. Silvestre, Ronald D. Stall; Data Coordinating Center (UM1-AI35043): The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Lisa P. Jacobson (PI), Gypsyamber D'Souza (PI), Alison Abraham, Keri Althoff, Michael Collaco, Priya Duggal, Sabina Haberlen, Eithne Keelaghan, Heather McKay, Alvaro Muñoz, Derek Ng, Anne Rostich, Eric C. Seaberg, Sol Su, Pamela Surkan, Nicholas Wada; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Robin E. Huebner; and the National Cancer Institute: Geraldina Dominguez; the Data Analysis and Coordination Center: Gypsyamber D'Souza, Stephen Gange, Elizabeth Golub (U01-HL146193-01) .

Disclaimer

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, or the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The MACS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with additional co-funding from the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Targeted supplemental funding for specific projects was also provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. MACS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR001079 (JHU Institute for Clinical and Translational Research) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences a component of the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Grant Nos. U01-AI35039, U01-AI35040, U01-AI35041, U01-AI35042, and UM1-AI35043), the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. R03-MH103961) and the Center for AIDS Research grant at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Scott RL, Lasiuk G, Norris C: The relationship between sexual orientation and depression in a national population sample. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:3522–3532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH: Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med 2015;38:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hatzenbuehler ML: How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull 2009;135:707–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mays VM, Cochran SD: Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1869–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thoits PA: Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51(Suppl.):S41–S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wight RG, LeBlanc AJ, Meyer IH, Harig FA: Internalized gay ageism, mattering, and depressive symptoms among midlife and older gay-identified men. Soc Sci Med 2015;147:200–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andersen JP, Zou C, Blosnich J: Multiple early victimization experiences as a pathway to explain physical health disparities among sexual minority and heterosexual individuals. Soc Sci Med 2015;133:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schneeberger AR, Dietl MF, Muenzenmaier KH, et al. : Stressful childhood experiences and health outcomes in sexual minority populations: A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014;49:1427–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Batten SV, Aslan M, Maciejewski PK, Mazure CM: Childhood maltreatment as a risk factor for adult cardiovascular disease and depression. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:249–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benjet C, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME: Chronic childhood adversity and onset of psychopathology during three life stages: Childhood, adolescence and adulthood. J Psychiatr Res 2010;44:732–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, et al. : Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:1319–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scott KM, Von Korff M, Angermeyer MC, et al. : Association of childhood adversities and early-onset mental disorders with adult-onset chronic physical conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:838–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herrick AL, Lim SH, Plankey MW, et al. : Adversity and syndemic production among men participating in the multicenter AIDS cohort study: A life-course approach. Am J Public Health 2013;103:79–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Infurna FJ, Rivers CT, Reich J, Zautra AJ: Childhood trauma and personal mastery: Their influence on emotional reactivity to everyday events in a community sample of middle-aged adults. PLoS One 2015;10:e0121840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manyema M, Norris SA, Richter LM: Stress begets stress: The association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health 2018;18:835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, et al. : The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol 1987;126:310–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Detels R, Jacobson L, Margolick J, et al. : The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1983 to… Public Health 2012;126:196–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dudley J, Jin S, Hoover D, et al. : The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: Retention after 9 1/2 years. Am J Epidemiol 1995;142:323–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tani Y, Fujiwara T, Kondo N, et al. : Childhood socioeconomic status and onset of depression among Japanese older adults: The JAGES Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;24:717–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Armstrong NM, Surkan PJ, Treisman GJ, et al. : Optimal metrics for identifying long term patterns of depression in older HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men. Aging Ment Health 2019;23:507–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herek GM: Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. J Interpers Violence 2009;24:54–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Katra G: Formation of homosexual orientation of men in adolescence. Pol Psychol Bull 2014;45:326–333 [Google Scholar]

- 24. The National Center for Victims of Crime. 2018 National Crime Victims' Rights Week Resource Guide: Crime and Victimization Fact Sheets—Urban and Rural Victimization. 2018. Available at https://ovc.ncjrs.gov/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_UrbanRural_508_QC.pdf Accessed June26, 2019

- 25. Martin-Storey A, Fish J: Victimization disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from ages 9 to 15. Child Dev 2019;90:71–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL: Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics 2009;124:1411–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Giga NM, et al. : The 2015 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation's Schools. New York, GLSEN, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bruce D, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA: Minority stress, positive identity development, and depressive symptoms: Implications for resilience among sexual minority male youth. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 2015;2:287–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Katz-Wise SL, Rosario M, Calzo JP, et al. : Associations of timing of sexual orientation developmental milestones and other sexual minority stressors with internalizing mental health symptoms among sexual minority young adults. Arch Sex Behav 2017;46:1441–1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Roberts AL, Rosario M, Slopen N, et al. : Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:143–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, et al. : Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: The Urban Men's Health Study. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC: Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. J Couns Psychol 2009;56:32–43 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, et al. : Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care 2010;22:630–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dew M, Becker J, Sanchez J, et al. : Prevalence and predictors of depressive, anxiety and substance use disorders in HIV-infected and uninfected men: A longitudinal evaluation. Psychol Med 1997;27:395–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gunn JM, Ayton DR, Densley K, et al. : The association between chronic illness, multimorbidity and depressive symptoms in an Australian primary care cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2012;47:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.