Abstract

Background: The reliability of long-term maternal recall of breastfeeding has been assessed previously, but not maternal milk expression (pumping) and child consumption of expressed milk.

Objective: To examine the reliability of maternal recall of feeding at the breast, maternal milk expression, and child consumption of expressed milk 6 years after delivery using the Brief Breastfeeding and Milk Expression Recall Survey (BaByMERS).

Methods: At 12 months postpartum, women who delivered a singleton, live-born infant at >24 weeks of gestation at a major U.S. academic hospital completed BaByMERS. Five years later, they were recontacted to complete the same questionnaire. Kappa statistics (κ), intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and Bland/Altman plots examined agreement. Sociodemographics were examined through stratified comparisons.

Results: Of 299 women who completed both questionnaires, 35% had a postgraduate education and 82% identified as white/Caucasian. Kappa statistics showed substantial agreement for ever breastfeeding or feeding breast milk (combined) (κ = 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.44–0.98) and ever feeding at the breast (κ = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.62–0.89). Recall for duration of feeding at the breast was excellent (ICC = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.95–0.97), and of maternal milk expression was slightly less so (ICC = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.80–0.97). Maternal minority race/ethnicity, lower educational attainment, unmarried marital status, public/no health insurance, and smoking were associated with lower reliability; these differences were usually small and not consistent across all feeding practices.

Conclusions: Maternal recall of contemporary lactation and infant feeding using BaByMERS was strongly reliable 6 years after delivery. BaByMERS may be useful to collect recall data, with attention to subpopulations that may exhibit lower recall reliability.

Keywords: recall bias, breastfeeding, milk expression, pumping, infant feeding practices, lactation

Introduction

Breastfeeding statistics commonly serve as a population-level indicator of maternal and child health, and accurate measurement of breastfeeding is important in research on the etiology of outcomes such as childhood asthma and allergies,1,2 overweight and obesity,2,3 cognitive development,2,4 as well as maternal cancers and type 2 diabetes.5 Most epidemiologic studies use retrospective data about breastfeeding that rely on maternal recall. However, if recall is poor, breastfeeding exposure may be misclassified and effect estimates may be biased as a result.

Several previous studies that examined maternal recall of breastfeeding showed that even though mothers tended to slightly overestimate their breastfeeding duration when queried after several years,6–13 maternal recall related to any breastfeeding (both for ever/never binary initiation and duration) remains strongly reliable, as evidenced by high correlation statistics.6,7,14–18 In samples with high rates of breastfeeding, agreement for breastfeeding initiation is almost perfect.7,8,14,19 Sociodemographic factors may affect recall accuracy, but the literature is mixed in terms of which factors are important. For instance, studies have reported that mothers who are multiparous,6,15 smokers,6 older,10 and have low educational attainment6,12,17 tend to have larger median recall bias toward overestimation and lower reliability (correlation statistics).

However, infant feeding practices have recently changed from predominantly feeding at the breast to including increasing amounts of maternal milk expression (pumping) and feeding children expressed milk, in addition or instead.20 To date, no studies evaluating recall have included assessment of maternal milk expression and feeding expressed milk.

Differentiating maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk from feeding at the breast is increasingly important as research emerges to suggest they may have differing effects on maternal and child health.21,22 The Brief Breastfeeding and Milk Expression Recall Survey (BaByMERS) captures a recalled history of each of these feeding practices, but how well women recall these practices after several years using the BaByMERS has not been examined.23 Evaluating recall reliability is an important part of validating such an interview tool for use in future research. Our objective in the present study was to compare maternal responses using the BaByMERS at 12 months and 6 years postpartum to evaluate the reliability of maternal recall using this tool.

Materials and Methods

Study population and data collection

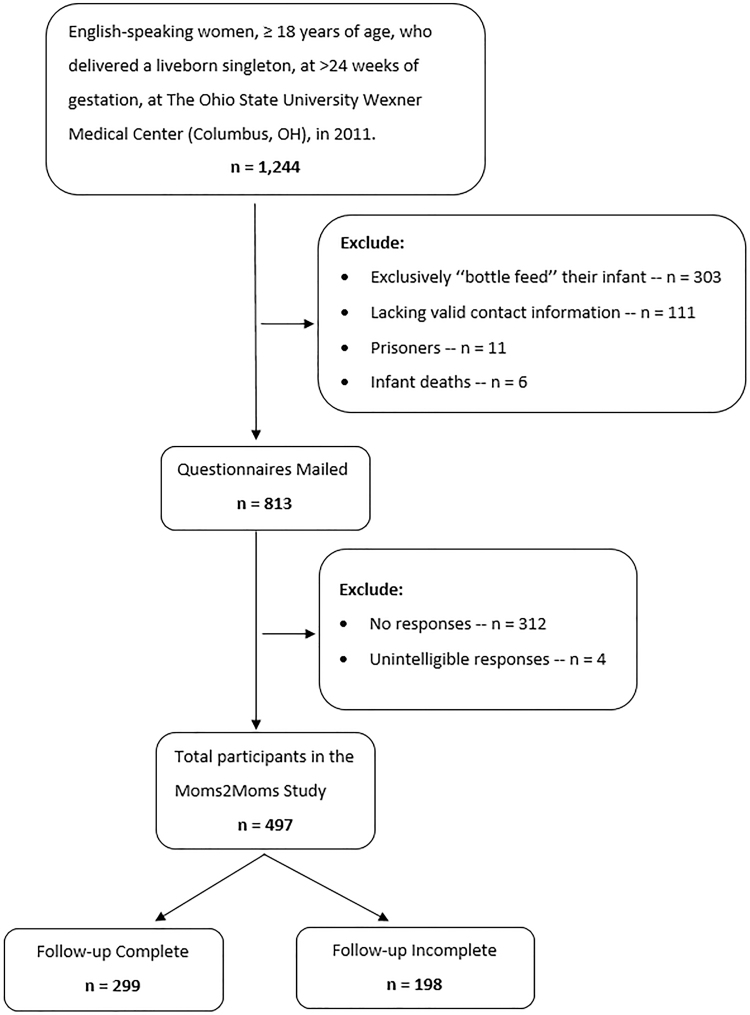

A list was assembled of all women who were at least 18 years of age and English speaking, who had delivered a live-born singleton at >24 weeks of gestation at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, during 5 months of 2011–12 (n = 1,244). Women who indicated at delivery that they planned to exclusively formula (“bottle”) feed their infant (n = 303), lacked valid contact information (n = 111), were prisoners (n = 11), or whose infants had died (n = 6) were excluded from the study.24

When the women were 12 months postpartum, the BaByMERS questionnaire was mailed to eligible women (n = 813) as part of the Moms2Moms Study to assess maternal lactation and infant feeding practices (Appendix Fig. A1). Maternal and child characteristics were gathered from the obstetric record and the questionnaire. The methods of this baseline (first phase) data collection have been reported in detail previously.24 Four hundred ninety-seven women completed the questionnaire with intelligible responses and received a $10 incentive.

In 2017–18, when the children were 6 years of age, these mothers were recontacted to complete the BaByMERS questionnaire again via telephone. Slight changes were made to this new version of the survey to improve clarity but not to change the meaning (Appendix Table A1). Participants who completed this follow-up study (second phase) received a $5 incentive.

Questionnaire and variables

The BaByMERS questionnaire assessed whether (initiation) and for how long (duration) the woman fed her infant at the breast, the woman expressed milk, and the child consumed expressed milk. Binary initiation variables (ever versus never) were created for each of those feeding and lactation practices: feeding at the breast, maternal milk expression, child consumption of expressed milk, as well as breastfeeding or feeding breast milk (based on the questions about feeding at the breast and child consumption of expressed milk) (Appendix Table A1). Continuous duration variables, such as feeding at the breast, maternal milk expression, child consumption of expressed milk, and breastfeeding or feeding breast milk, were calculated in days, as the difference between the age of the child at starting and stopping each feeding practice, including the day of delivery. For women who were still participating in a particular feeding practice at 12 months after delivery, the duration was considered 365 days for the data from the first time point. Values >365 days reported at the second time point were also set to 365 days for comparability.

Maternal and child characteristics gathered at the first administration of BaByMERS included maternal age at delivery (from the obstetric record, categorized as ≤30 versus >30 years in stratified analysis); race (white/Caucasian, black/African American, other); ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic); education (high school/General Educational Development [GED] or less, some college/associate's degree, bachelor's degree, postgraduate degree); marital status (married/living with partner versus unmarried/not living with partner); parity (from the obstetric record, primiparous versus multiparous); smoking status during pregnancy (yes versus no); reception of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) benefits during pregnancy or infancy (yes versus no); annual household income (<$35,000 versus ≥ $35,000); insurance type (from the obstetric record, public or no health insurance versus private insurance); whether the mother ever went to work or school 20+ hours per week in the first year postpartum (yes versus no); child's sex (from the obstetric record); cesarean section (from the obstetric record, yes versus no for vaginal delivery); birth maturity (from the obstetric record, preterm birth versus term birth); and birth weight (from the obstetric record, categorized as ≤3.3 kg versus >3.3 kg in stratified analysis).

Statistical analysis

Chi-square, two-sample t, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to compare sociodemographic characteristics among follow-up study responders (completed the BaByMERS at both time points) and nonresponders (completed the BaByMERS at only the first time point). The Shapiro/Wilk test was used to check the normality of continuous sociodemographic variables.

The Kappa statistic was applied to assess the agreement between maternal responses at 6 years postdelivery (“recalled”) with responses at 12 months postdelivery (“recorded”) for binary initiation variables for each feeding practice. The agreement was considered to be moderate if 0.40 < κ ≤ 0.60, to be substantial if 0.60 < κ ≤ 0.80, and to be almost perfect if κ > 0.80.25 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated based on a single-rater, absolute agreement, two-way effects model to examine the proportion of the paired feeding duration variance over the total variance. Strong reliability was considered if 0.75 < ICC ≤0.90 and excellent reliability was considered if ICC >0.90.26 After calculating the ICC for the full sample, including mothers with 0 duration of a given feeding practice, we stratified the sample by sociodemographic factors to identify subgroups with particularly excellent or poor recall. The differences between the durations reported at the two time points were calculated as recalled minus recorded. Over/underestimation error was defined as recalled duration more than 30 days more/less than the recorded duration. Bland/Altman plots displayed the mean and the ±1.96 standard deviations (SD) of the differences between the paired recorded and recalled feeding durations.27 All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Of the 497 participants who answered the recorded BaByMERS at 12 months after delivery, 299 completed the recalled questionnaire 6 years after delivery (Appendix Fig. A1), the “follow-up complete” group (Table 1). Participants who were nonresponsive, could not be located, or refused the invitation to the second phase were defined as a “follow-up incomplete” group (n = 198). The 299 participants who completed the follow-up study comprised a diverse sample: 35% mothers had a postgraduate education, half were primiparous at the time of the first phase, 6% smoked during pregnancy, a quarter enrolled in WIC during pregnancy or the first year postpartum, 27% had income <$35,000, and 15% had no health insurance or public insurance; more than one-third of infants were delivered by cesarean section. Mothers who delivered at term, had higher educational attainment, higher annual household income, private insurance, and did not enroll in WIC were more likely to complete the follow-up study 6 years postpartum.

Table 1.

Maternal and Child Characteristics at Baseline, Moms2Moms Study and Follow-Up (n = 497)

| Characteristics | Total participants (n = 497) | Follow-up incomplete (n = 198) | Follow-up complete (n = 299) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age at delivery (years), mean (SD) | 30.2 (4.9) | 29.7 (5.4) | 30.5 (4.5) | 0.09a |

| Race, n (%) | 0.12b | |||

| White/Caucasian | 391 (78.7) | 147 (74.2) | 244 (81.6) | |

| Black/African American | 55 (11.0) | 24 (12.1) | 31 (10.4) | |

| Other | 50 (10.0) | 26 (13.1) | 24 (8.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.85b | |||

| Hispanic | 24 (4.8) | 10 (5.1) | 14 (4.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 473 (95.2) | 188 (95.0) | 285 (95.3) | |

| Education, n (%) | <0.01b | |||

| High school/GED or less | 68 (13.7) | 36 (18.2) | 32 (10.7) | |

| Some college/associate's degree or less | 92 (18.5) | 47 (23.7) | 45 (15.1) | |

| Bachelor's degree | 176 (35.4) | 59 (29.8) | 117 (39.1) | |

| Postgraduate degree | 159 (32.0) | 54 (27.3) | 105 (35.1) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.16b | |||

| Married/living with partner | 439 (88.3) | 169 (85.4) | 270 (90.3) | |

| Unmarried/not living with partner | 56 (11.3) | 27 (13.6) | 29 (9.7) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Parity, n (%) | 0.07b | |||

| Primiparous | 248 (49.9) | 89 (45.0) | 159 (53.2) | |

| Multiparous | 249 (50.1) | 109 (55.1) | 140 (46.8) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy, n (%) | 0.06b | |||

| Yes | 39 (7.8) | 21 (10.6) | 18 (6.0) | |

| No | 456 (91.8) | 175 (88.4) | 281 (94.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| WIC enrollment in pregnancy or infancy, n (%) | 0.02b | |||

| Yes | 139 (28.0) | 67 (33.8) | 72 (24.1) | |

| No | 355 (71.4) | 129 (65.2) | 226 (75.6) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Annual household income <$35,000, n (%) | 0.01b | |||

| Yes | 153 (30.8) | 73 (36.9) | 80 (26.8) | |

| No | 341 (68.6) | 123 (62.1) | 218 (72.9) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Public or no health insurance, n (%) | <0.0001b | |||

| Yes | 108 (21.7) | 62 (31.8) | 46 (15.4) | |

| No | 388 (78.1) | 135 (68.2) | 253 (84.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mom ever went to work/school 20+ hours/week | 0.70b | |||

| Yes | 340 (68.4) | 137 (69.2) | 203 (67.9) | |

| No | 156 (31.4) | 60 (30.3) | 96 (32.1) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Child's characteristics | ||||

| Sex, n (%) | 0.66b | |||

| Male | 255 (51.3) | 104 (52.5) | 151 (50.5) | |

| Female | 242 (48.7) | 94 (47.5) | 148 (49.5) | |

| Cesarean section delivery, n (%) | 0.58b | |||

| Yes | 186 (37.4) | 76 (38.4) | 110 (36.8) | |

| No | 282 (56.7) | 108 (54.6) | 174 (58.2) | |

| Missing | 29 (5.8) | 14 (7.0) | 15 (5.0) | |

| Birth maturity, n (%) | <0.01b | |||

| Preterm birth | 58 (11.7) | 35 (17.8) | 23 (7.7) | |

| Term birth | 439 (88.3) | 163 (82.3) | 276 (92.3) | |

| Birth weight (kg), median (IQR) | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.6) | 0.06c |

Shapiro/Wilk test was used to check the normality of continuous sociodemographics. Normal continuous variable—age at delivery—is shown as mean and SD; non-normal continuous variable—birth weight—is shown as median and IQR.

Two-sample t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables.

Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for non-normally distributed continuous variables.

GED, general educational development; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

The Kappa statistics showed substantial agreement between the two time points for initiations of feeding at the breast (κ = 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.62–0.89), maternal milk expression (κ = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.83), and breastfeeding or feeding breast milk (κ = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.44–0.98) (Table 2). Only moderate agreement was observed for initiations of child consumption of expressed milk (κ = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.33–0.63).

Table 2.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Values for Initiation (Ever/Never) of Each Feeding Practice, Moms2Moms Follow-Up (n = 299)

| Feeding and lactation practices | n | Kappa | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding at the breast (ever/never) | 296 | 0.76 | 0.62–0.89 |

| Maternal milk expression (ever/never) | 296 | 0.67 | 0.51–0.83 |

| Child consumption of expressed milk (ever/never) | 297 | 0.48 | 0.33–0.63 |

| Breastfeeding or feeding Breast milk (ever/never) | 297 | 0.71 | 0.44–0.98 |

Missing data: three missing for recalled initiation of feeding at the breast and recalled initiation of maternal milk expression, two missing for recalled initiation of child consumption of expressed milk and recalled initiation of breastfeeding or feeding breast milk.

CI, confidence interval.

The reliability of maternal recall for durations of feeding at the breast, and breastfeeding or feeding breast milk, was excellent (ICC = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.95–0.97 and ICC = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.92–0.95, respectively), and maternal recall for durations of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk was slightly less reliable but still strong (ICC = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.80–0.87 and ICC = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.72–0.81, respectively) (Table 3). More than half of the mothers could recall the durations of all feeding or lactation practices to within 1 month.

Table 3.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Duration of Each Feeding Practice, Moms2Moms Follow-Up (n = 299)

| Feeding and lactation practices | n | Recorded median (IQR) (days) | Recalled median (IQR) (days) | Median of differences (IQR) | Underestimation error >30 days (%) | Overestimation error >30 days (%) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding at the breast | 296 | 180 (323) | 188 (320) | 0 (15) | 17 (5.7) | 41 (13.9) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Maternal milk expression | 293 | 150 (215) | 179 (242) | 0 (49) | 54 (18.4) | 70 (23.9) | 0.83 (0.80–0.87) |

| Child consumption of expressed milk | 289 | 148 (223) | 160 (262) | 3 (49) | 49 (17.0) | 79 (27.3) | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) |

| Breastfeeding or feeding breast milk | 296 | 239 (275) | 255 (245) | 0 (30) | 12 (4.1) | 58 (19.6) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

Difference = Recalled duration − Recorded duration.

Missing data: 3 missing for recalled duration of feeding at the breast and recalled duration of breastfeeding or feeding breast milk, 6 missing for recalled duration of maternal milk expression, and 10 missing for recalled duration of child consumption of expressed milk.

CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IQR, interquartile range.

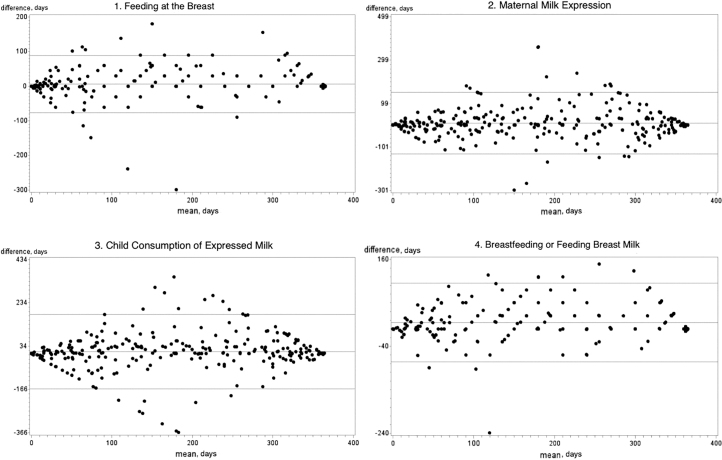

The Bland/Altman plots showed the bias between each paired recorded and recalled duration value (Fig. 1). Mothers tended to slightly overestimate the durations of all the feeding or lactation practices when they recalled them (difference = 6.4 days, SD = 41.3 for feeding at breast; difference = 9.6 days, SD = 70.4 for maternal milk expression; difference = 8.7 days, SD = 85.5 for child consumption of expressed milk; difference = 14.8 days, SD = 45.4 for breastfeeding or feeding breast milk).

FIG. 1.

Bland/Altman plots for bias between recorded and recalled durations of each feeding practice, Moms2Moms follow-up (n = 299).

When stratified by participant characteristics, the reliability of maternal recall for the feeding practice duration variables was fairly consistent and high across subgroups with a few exceptions. Mothers who identified as a race other than white/Caucasian or black/African American, Hispanic women, and women with a high school/GED or less education tended to have a poorer recall reliability for the duration of child consumption of expressed milk (ICC = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.19–0.77; ICC = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.13–0.83; ICC = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.35–0.79; respectively), although the CIs overlapped with that of all mothers (ICC = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.72–0.81) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Duration of Child Consumption of Expressed Milk, by Maternal and Child Characteristics (n = 289)

| Characteristics | n | Recorded median (IQR) (days) | Recalled median (IQR) (days) | Median of differences (IQR) | Underestimation error >30 days (%) | Overestimation error >30 days (%) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| All moms | 289 | 148 (223) | 160 (262) | 3 (49) | 49 (17.0) | 79 (27.3) | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) |

| Age at delivery (years) | |||||||

| ≤30 | 151 | 120 (219) | 148 (241) | 2 (50) | 27 (17.8) | 43 (28.5) | 0.78 (0.71–0.84) |

| >30 | 138 | 162 (244) | 184 (245) | 5 (48) | 22 (15.9) | 36 (26.1) | 0.74 (0.66–0.81) |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 238 | 152 (221) | 181 (249) | 7 (51) | 41 (17.2) | 69 (30.0) | 0.77 (0.72–0.82) |

| Black/African American | 30 | 61 (178) | 51 (199) | 0 (3) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (20.0) | 0.85 (0.73–0.93) |

| Other | 21 | 106 (216) | 121 (271) | 0 (51) | 5 (23.8) | 4 (19.1) | 0.46 (0.19–0.77) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 12 | 63 (169) | 76 (225) | -6 (54) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 0.45 (0.13–0.83) |

| Non-Hispanic | 277 | 149 (220) | 178 (260) | 3 (49) | 46 (16.6) | 77 (27.8) | 0.78 (0.73–0.82) |

| Education | |||||||

| High school/GED or less | 30 | 29 (120) | 29 (151) | 0 (54) | 7 (23.3) | 8 (26.7) | 0.58 (0.35–0.79) |

| Some college/associate's degree | 43 | 61 (175) | 77 (259) | 0 (66) | 6 (14.0) | 11 (25.6) | 0.77 (0.62–0.86) |

| Bachelor's degree | 114 | 151 (211) | 198 (244) | 8 (57) | 17 (14.9) | 35 (30.7) | 0.78 (0.70–0.84) |

| Postgraduate degree | 102 | 211 (226) | 210 (241) | 2 (46) | 19 (18.6) | 25 (24.5) | 0.73 (0.64–0.81) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 260 | 151 (214) | 180 (249) | 3 (53) | 48 (18.5) | 70 (26.9) | 0.74 (0.68–0.79) |

| Unmarried/not living with partner | 29 | 53 (136) | 54 (180) | 1 (33) | 1 (3.5) | 9 (31.0) | 0.96 (0.92–0.98) |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primiparous | 154 | 178 (235) | 197 (253) | 3 (45) | 24 (15.6) | 38 (24.7) | 0.81 (0.75–0.86) |

| Multiparous | 135 | 107 (214) | 137 (242) | 3 (60) | 25 (18.5) | 41 (30.8) | 0.70 (0.61–0.78) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 46 (133) | 31 (180) | 6 (61) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (22.2) | 0.91 (0.78–0.96) |

| No | 271 | 151 (216) | 180 (251) | 3 (49) | 44 (16.2) | 75 (27.7) | 0.75 (0.70–0.80) |

| WIC enrollment in pregnancy or infancy | |||||||

| Yes | 67 | 60 (163) | 54 (199) | 0 (40) | 10 (14.9) | 16 (23.9) | 0.79 (0.68–0.86) |

| No | 221 | 176 (219) | 196 (240) | 5 (51) | 38 (17.2) | 63 (28.5) | 0.75 (0.68–0.80) |

| Annual household income <$35,000 | |||||||

| Yes | 75 | 74 (176) | 90 (197) | 0 (53) | 15 (20.0) | 17 (22.7) | 0.76 (0.66–0.84) |

| No | 213 | 170 (216) | 206 (251) | 6 (51) | 34 (16.0) | 62 (29.1) | 0.75 (0.69–0.80) |

| Public or no health insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 43 | 59 (172) | 56 (210) | 0 (25) | 6 (14.0) | 7 (16.3) | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) |

| No | 246 | 160 (216) | 181 (250) | 5 (57) | 43 (17.5) | 72 (29.3) | 0.72 (0.66–0.78) |

| Mom ever went to work/school 20+ hours/week | |||||||

| Yes | 198 | 149 (215) | 174 (250) | 7 (54) | 32 (16.2) | 60 (30.3) | 0.79 (0.73–0.84) |

| No | 91 | 118 (245) | 151 (292) | 2 (49) | 17 (18.7) | 19 (20.9) | 0.71 (0.61–0.80) |

| Child's characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 146 | 144 (234) | 157 (246) | 0 (54) | 30 (20.6) | 37 (25.3) | 0.76 (0.68–0.82) |

| Female | 143 | 149 (215) | 178 (250) | 8 (49) | 19 (13.3) | 42 (29.4) | 0.78 (0.71–0.83) |

| Birth maturity | |||||||

| Preterm birth | 23 | 119 (212) | 120 (203) | 0 (57) | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 0.95 (0.89–0.98) |

| Term birth | 266 | 149 (221) | 174 (260) | 4 (49) | 45 (16.9) | 74 (27.8) | 0.75 (0.70–0.80) |

| Birth weight (kg) | |||||||

| ≤3.3 | 129 | 120 (218) | 151 (231) | 0 (47) | 21 (16.3) | 33 (25.6) | 0.72 (0.63–0.80) |

| >3.3 | 160 | 151 (222) | 180 (276) | 8 (49) | 28 (17.5) | 46 (28.8) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) |

Difference = Recalled duration − Recorded duration.

Missing data: 10 missing for recalled duration of child consumption of expressed milk, therefore n = 289.

CI, confidence interval; GED, general educational development; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IQR, interquartile range; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Compared with the full sample (ICC = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.95–0.97, Appendix Table A2), mothers who were black/African American, unmarried/not living with a partner, or with public/no health insurance had slightly lower recall reliability on the duration of feeding at the breast (ICC = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.72–0.92; ICC = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.77–0.94; ICC = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.85–0.95; respectively), but these estimates were close to those for the full sample. On the duration of breastfeeding or feeding breast milk (median of differences for the full sample = 0 days, interquartile range [IQR] = 30 days, ICC = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.92–0.95) (Appendix Table A3), mothers who smoked during pregnancy tended to have a larger median recall bias toward overestimation (median = 30 days, IQR = 31 days), and Hispanic mothers had a lower recall reliability (ICC = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.43–0.91). In contrast with the full sample on the duration of maternal milk expression (ICC = 0.83, 95% CI = 0.80–0.87) (Appendix Table A4), women who identified as a race other than white/Caucasian or black/African American and who had a high school/GED or less education reported less reliably (ICC = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.32–0.80; ICC = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.36–0.79; respectively).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, maternal recall of infant feeding and maternal lactation practices was strongly reliable 6 years after delivery, although the recall of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk was somewhat less than feeding at the breast. More than three-fourths of the mothers were able to accurately recall their recorded durations of feeding at the breast and breastfeeding or feeding breast milk to within 1 month. The reliability of maternal recall was somewhat reduced for some subgroups distinguished by minority race or ethnicity, lower economic status, or smoking. This was not consistent across feeding practices and was generally of small to moderate magnitude.

Amissah et al. found that maternal recall of breastfeeding duration was valid 6 years after childbirth with a 1-week bias toward overestimation (ICC = 0.84); and smoking and low educational attainment stood out as the main factors associated with lower recall validity (ICC = 0.61; ICC = 0.63, separately).6 Natland et al. reported the accuracy of 20-year maternal recall for breastfeeding initiation and duration was high (κ = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.82–0.88; ICC = 0.82), with a modest median overestimation of 2 weeks.7 The review article written by Li et al. also examined the reliability of maternal recall for both breastfeeding initiation and duration after years, based on 11 studies published between 1966 and 2003.17 Beyond their studies, we assessed the reliability of maternal recall for each separate feeding and lactation practice using our unique BaByMERS: feeding at the breast, maternal milk expression, child consumption of expressed milk, and breastfeeding or feeding breast milk (combined), on both initiation and duration variables. Demographic factors that may affect maternal recall were also tested in our study.

Around a quarter of mothers recalled the durations of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk to be more than a month longer than recorded, although the recall reliability remained high. As shown in previous studies, the higher the rates of breastfeeding, the stronger the reliability of maternal recall.7,14 The prevalence of feeding at the breast in our sample was 98%, whereas the prevalence of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk was 91%. Furthermore, the median recorded duration of feeding at the breast was 1 month longer than that of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk. Therefore, it was reasonable that the reliability of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk was lower than that of feeding at the breast.

Some subgroups defined by maternal race/ethnicity, education, marital status, insurance type, and smoking had somewhat poorer maternal recall reliability, but not consistently across all feeding or lactation practices. Only a few studies have examined how sociodemographic factors could potentially affect the reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding behaviors.6,10,15,17 Findings from those studies have been inconclusive. Li et al. reported that differences in recall by maternal race/ethnicity, education, and socioeconomic status may have stemmed from differences in social norms or beliefs or communication quality with the interviewers.17 They explained that the reason of overestimation of breastfeeding among wealthier and more educated mothers may be according to their beliefs or those of the interviewers.17 It may also be that lower educational attainment was related to poorer understanding of the questions, especially for new concepts such as milk expression. Prior studies have reported that mothers with lower socioeconomic status recalled more poorly on traditional breastfeeding questions.15,17,28 Alternatively, these sociodemographic factors may simply reflect the fact that women in these subgroups had shorter durations for each feeding practice, on average, and prior research has shown that shorter duration is associated with poorer recall, as mentioned previously.7,9,14

The present study is unique because it was the first study to examine maternal recall of maternal milk expression and child consumption of expressed milk. It validated maternal recall reliability based on both feeding initiation (binary ever/never) and duration (continuous) variables. It was a longitudinal, prospective cohort study. Also, this was one of the very few studies to assess how sociodemographic factors may affect breastfeeding recall.

A limitation of the study was that the study sample came from a single clinical site, so the results may not be generalizable to all U.S. women. Second, as with any longitudinal study, loss to follow-up affected a portion of the sample, and some background characteristics differed between the original sample and the follow-up sample. Our estimates may have been affected by differential loss to follow-up. Third, we were able to compare self-reported feeding practices at two time points, rather than to compare self-report with an ideal gold standard that would be unaffected by self-report. Thus, inaccurate reporting was a possibility at both time points. However, self-report is the typical method to measure breastfeeding in epidemiologic research, so our data reflect typical practice. Also, it is possible that if the BaByMERS had been administered at the first phase as an interview rather than self-administered questionnaire, reliability may have been even higher. We have previously reported that the interview version of the BaByMERS has high concordance with responses to commonly used breastfeeding questions in federal child health surveys and may perform better for capturing expressed milk feeding.29 Finally, around a quarter of the mothers continued feeding at the breast, and two mothers continued feeding their child expressed breast milk beyond 12 months postpartum. The durations of these practices at both time points were truncated to 365 days. This could lead to a small overestimation of the accuracy of maternal recall on all feeding durations.

Conclusion

Maternal recall of child consumption of expressed milk, maternal milk expression, and feeding at the breast was strong to excellent after 6 years after delivery using BaByMERS. Overall, BaByMERS exhibits acceptable accuracy in capturing the recall history of these contemporary feeding and lactation practices after several years, and can be used as an interview tool for recording infant feeding and maternal lactation in future research. Future researchers should consider that the reliability was lower for some practices among women from racial and ethnic minority groups, women with less educational attainment, unmarried women, women with public or no health insurance, and those who smoked, although this was not consistent across feeding practices and was generally of small to moderate magnitude.

Acknowledgments

We thank the women who participated in the Moms2Moms Follow-up Study and Kelly Boone, Chelsea Dillon, Kendra Heck, Rachel Ronau, Hanna Schlaack, Erin Shafer, Thalia Cronin, Justin Jackson, and Kamma Smith (Nationwide Children's Hospital) for data collection and administrative support.

Appendix

Appendix Fig. A1.

Participant flow diagram, Moms2Moms follow-up study.

Appendix Table A1.

Brief Breastfeeding and Milk Expression Recall Survey

| Construct measured | 12-months postpartum (recorded) |

6-years postpartum (recalled) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Answer options | Questions | Answer options | |

| Feeding at the breast | 1. How old was [child] when you first directly breastfed him/her at your breast? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Write “0” if you never directly breastfed your child | 1. Was [child] ever breastfed directly at the breast? | Yes | No | Refused | Don't know [if No, Refused, Don't know, skip to 4] |

| 2. How old was [child] when [he/she] started feeding at the breast? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Refused | Don't know | |||

| 2. How old was [child] when you stopped directly breastfeeding him/her at your breast? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still directly breastfeeding your child | Write “0” if you never directly breastfed your child | 3. How old was [child] when [he/she] completely stopped feeding at the breast? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still feeding at the breast | Refused | Don't know | |

| Maternal milk expression | The next couple of questions are about expressing your breast milk using a breast pump or your hands. | |||

| 3. When after your delivery did you first start to pump your breast milk to be fed to your own child? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Write “0” if you never pumped your breast milk | 4. Did you ever use a breast pump or your hands to express milk for [child]? | Yes | No | Refused | Don't know [if No, Refused, Don't know, skip to 7] | |

| 5. How old was [child] when you started using a breast pump or your hands to express your breast milk? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Refused | Don't know | |||

| 4. When after your delivery did you stop pumping your breast milk to be fed to your own child? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still pumping breast milk | Write “0” if you never pumped your breast milk | 6. How old was [child] when you stopped using a breast pump or your hands to express your breast milk? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still expressing breast milk | Refused | Don't know | |

| Child consumption of expressed milk | 5. How old was [child] when [he/she] was first fed any of your pumped breast milk? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Write “0” if your child was never fed your pumped milk | 7. Did [child] ever drink expressed breast milk? | Yes | No | Refused | Don't know [if No, Refused, Don't know, stop] |

| 8. How old was [child] when [he/she] started drinking expressed breast milk? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Refused | Don't know | |||

| 6. How old was [child] when [he/she] was no longer fed any of your pumped breast milk? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still feeding pumped breast milk | Write “0” if your child was never fed your pumped milk | 9. How old was [child] when [he/she] completely stopped drinking expressed breast milk? Include fresh and frozen breast milk and breast milk mixed in cereal. | Number in days, weeks, or months | Still drinking expressed breast milk | Refused | Don't know | |

| Breastfeeding or feeding breast milk | 7. How old was [child] when [he/she] was first fed your breast milk (including directly at your breast or pumped milk)? | Number in days, weeks, or months | Write “0” if never fed your child breast milk | Initiation: Derived from 1 to 7 above | If 1 = “Yes” or 7 = “Yes” then Yes. |

| If 1 = “No” and 7 = “No” then No. | ||||

| 8. How old was [child] when [he/she] was no longer fed your breast milk (either directly at your breast or pumped milk)? | Number in days, weeks, or months |Still feeding your child breast milk (either directly at your breast or pumped milk) | Write “0” if you never fed your child your breast milk | Duration: Derived from 2, 3, 8, 9 above | Maximum value among 3 − 2 and 9 − 8 | |

Appendix Table A2.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Duration of Feeding at the Breast, by Maternal and Child Characteristics (n = 296)

| Characteristics | n | Recorded median (IQR) (days) | Recalled median (IQR) (days) | Median of differences (IQR) | Underestimation error >30 days (%) | Overestimation error >30 days (%) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| All moms | 296 | 180 (323) | 188 (320) | 0 (15) | 17 (5.7) | 41 (13.9) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Age at delivery (years) | |||||||

| ≤30 | 152 | 150 (300) | 180 (323) | 0 (29) | 10 (6.6) | 24 (15.8) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) |

| >30 | 144 | 270 (305) | 285 (305) | 0 (6) | 7 (4.9) | 17 (11.8) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 243 | 180 (321) | 210 (309) | 0 (16) | 13 (5.4) | 32 (13.2) | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) |

| Black/African American | 31 | 90 (212) | 120 (212) | 0 (45) | 2 (6.5) | 8 (25.8) | 0.85 (0.72–0.92) |

| Other | 22 | 288 (276) | 273 (351) | 0 (5) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (4.6) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 13 | 98 (335) | 180 (314) | 0 (31) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.91 (0.76–0.97) |

| Non-Hispanic | 283 | 180 (322) | 210 (321) | 0 (15) | 17 (6.0) | 38 (13.4) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Education | |||||||

| High school/GED or less | 31 | 90 (284) | 120 (210) | 0 (30) | 4 (12.9) | 6 (19.4) | 0.94 (0.89–0.97) |

| Some college/associate's degree | 44 | 90 (249) | 75 (283) | 0 (11) | 3 (6.8) | 4 (9.1) | 0.94 (0.89–0.96) |

| Bachelor's degree | 117 | 180 (316) | 210 (295) | 0 (30) | 4 (3.4) | 19 (16.2) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Postgraduate degree | 104 | 300 (275) | 285 (275) | 0 (5) | 6 (5.8) | 12 (11.5) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 267 | 210 (309) | 210 (307) | 0 (15) | 16(6.0) | 37 (13.9) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Unmarried/not living with partner | 29 | 60 (200) | 120 (159) | 0 (15) | 1 (3.5) | 4 (13.8) | 0.88 (0.77–0.94) |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primiparous | 158 | 180 (322) | 203 (314) | 0 (14) | 8 (5.1) | 23 (14.6) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) |

| Multiparous | 138 | 195 (327) | 180 (326) | 0 (27) | 9 (6.5) | 18 (13.0) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 52 (114) | 53 (180) | 0 (17) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.6) | 0.97 (0.92–0.99) |

| No | 278 | 210 (316) | 210 (308) | 0 (14) | 16 (5.8) | 40 (14.4) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| WIC enrollment in pregnancy or infancy | |||||||

| Yes | 70 | 90 (270) | 120 (249) | 0 (21) | 7 (10.0) | 11 (15.7) | 0.93 (0.90–0.96) |

| No | 225 | 238 (302) | 240 (295) | 0 (14) | 10 (4.4) | 30 (13.3) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Annual household income <$35,000 | |||||||

| Yes | 78 | 117 (276) | 127 (248) | 0 (21) | 5 (6.4) | 12 (15.4) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) |

| No | 217 | 238 (305) | 240 (295) | 0 (14) | 12 (5.5) | 29 (13.4) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Public or no health insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 44 | 95 (263) | 98 (234) | 0 (21) | 5 (11.4) | 7 (15.9) | 0.91 (0.85–0.95) |

| No | 252 | 210 (305) | 237 (305) | 0 (14) | 12 (4.7) | 34 (13.5) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Mom ever went to work/school 20+ hours/week | |||||||

| Yes | 201 | 150 (288) | 180 (304) | 0 (30) | 12 (6.0) | 35 (17.4) | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) |

| No | 95 | 300 (322) | 300 (335) | 0 (0) | 5 (5.3) | 6 (6.3) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

| Child's characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 148 | 180 (323) | 210 (304) | 0 (25) | 8 (5.4) | 27 (18.2) | 0.97 (0.95–0.98) |

| Female | 148 | 180 (328) | 180 (326) | 0 (10) | 9 (6.1) | 14 (9.5) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) |

| Birth maturity | |||||||

| Preterm birth | 23 | 13 (220) | 30 (178) | 0 (12) | 4 (17.4) | 4 (17.4) | 0.95 (0.89–0.98) |

| Term birth | 273 | 210 (307) | 210 (305) | 0 (15) | 13 (4.8) | 37 (13.6) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

| Birth weight (kg) | |||||||

| ≤3.3 | 131 | 120 (316) | 160 (331) | 0 (8) | 9 (6.8) | 15 (11.5) | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) |

| >3.3 | 165 | 240 (309) | 240 (275) | 0 (27) | 8 (4.9) | 26 (15.8) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) |

Difference = Recalled duration − Recorded duration.

Missing data: three missing for recalled duration of feeding at the breast, therefore n = 296.

CI, confidence interval; GED, general educational development; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IQR, interquartile range; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Appendix Table A3.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Duration of Breastfeeding or Feeding Breast Milk, by Maternal and Child Characteristics (n = 296)

| Characteristics | n | Recorded median (IQR) (days) | Recalled median (IQR) (days) | Median of differences (IQR) | Underestimation error >30 days (%) | Overestimation error >30 days (%) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| All moms | 296 | 239 (275) | 255 (245) | 0 (30) | 12 (4.1) | 58 (19.6) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

| Age at delivery (years) | |||||||

| ≤30 | 152 | 180 (299) | 210 (274) | 0 (30) | 7 (4.6) | 32 (21.1) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

| >30 | 144 | 300 (245) | 330 (216) | 0 (21) | 5 (3.5) | 26 (18.1) | 0.93 (0.90–0.95) |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 243 | 240 (275) | 270 (245) | 0 (30) | 9 (3.7) | 49 (20.2) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

| Black/African American | 30 | 120 (209) | 158 (198) | 1 (45) | 1 (3.3) | 8 (26.7) | 0.87 (0.76–0.93) |

| Other | 23 | 330 (216) | 343 (309) | 0 (19) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.4) | 0.94 (0.88–0.97) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 13 | 165 (290) | 240 (215) | 0 (31) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0.75 (0.43–0.91) |

| Non-Hispanic | 283 | 240 (275) | 270 (245) | 0 (30) | 12 (4.2) | 55 (19.4) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) |

| Education | |||||||

| High school/GED or less | 30 | 119 (270) | 120 (242) | 2 (30) | 2 (6.7) | 7 (23.3) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) |

| Some college/associate's degree | 44 | 120 (258) | 170 (241) | 0 (24) | 2 (4.6) | 9 (20.5) | 0.91 (0.85–0.95) |

| Bachelor's degree | 117 | 231 (245) | 240 (215) | 0 (30) | 3 (2.6) | 26 (22.2) | 0.92 (0.88–0.94) |

| Postgraduate degree | 105 | 330 (215) | 354 (187) | 0 (15) | 5 (4.8) | 16 (15.2) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 267 | 240 (246) | 270 (239) | 0 (30) | 11 (4.1) | 49 (18.4) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

| Unmarried/not living with partner | 29 | 117 (183) | 120 (198) | 11 (36) | 1 (3.5) | 9 (31.0) | 0.89 (0.78–0.94) |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primiparous | 159 | 210 (246) | 240 (245) | 0 (30) | 5 (3.1) | 24 (15.1) | 0.94 (0.92–0.95) |

| Multiparous | 137 | 240 (275) | 270 (245) | 0 (30) | 7 (5.1) | 29 (21.2) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 76 (153) | 120 (189) | 30 (31) | 1 (5.6) | 5 (27.8) | 0.95 (0.87–0.98) |

| No | 278 | 240 (248) | 270 (245) | 0 (30) | 11 (4.0) | 53 (19.1) | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) |

| WIC enrollment in pregnancy or infancy | |||||||

| Yes | 69 | 120 (258) | 120 (258) | 0 (30) | 5 (7.3) | 15 (21.7) | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) |

| No | 226 | 269 (245) | 300 (215) | 0 (30) | 7 (3.1) | 43 (19.0) | 0.93 (0.90–0.94) |

| Annual household income <$35,000 | |||||||

| Yes | 78 | 120 (277) | 180 (254) | 0 (30) | 4 (5.1) | 16 (20.5) | 0.95 (0.92–0.96) |

| No | 217 | 269 (245) | 300 (215) | 0 (30) | 8 (3.7) | 42 (19.4) | 0.93 (0.90–0.94) |

| Public or no health insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 43 | 120 (243) | 120 (258) | 0 (31) | 3 (7.0) | 9 (20.9) | 0.93 (0.88–0.96) |

| No | 253 | 240 (245) | 270 (230) | 0 (30) | 9 (3.6) | 49 (19.4) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) |

| Mom ever went to work/school 20+ hours/week | |||||||

| Yes | 201 | 180 (270) | 234 (242) | 0 (31) | 9 (4.5) | 51 (25.4) | 0.91 (0.88–0.93) |

| No | 95 | 330 (245) | 360 (245) | 0 (3) | 3 (3.2) | 7 (7.4) | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) |

| Child's characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 149 | 240 (275) | 270 (239) | 0 (30) | 5 (3.4) | 32 (21.5) | 0.95 (0.93–0.96) |

| Female | 147 | 210 (275) | 240 (248) | 0 (30) | 7 (4.8) | 26 (17.7) | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) |

| Birth maturity | |||||||

| Preterm birth | 23 | 148 (241) | 160 (204) | 0 (26) | 4 (17.4) | 5 (21.7) | 0.96 (0.91–0.98) |

| Term birth | 273 | 270 (245) | 270 (245) | 0 (30) | 8 (2.9) | 53 (19.4) | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) |

| Birth weight (kg) | |||||||

| ≤3.3 | 131 | 180 (292) | 210 (273) | 0 (30) | 7 (5.3) | 24 (18.3) | 0.91 (0.87–0.93) |

| >3.3 | 165 | 270 (245) | 285 (215) | 0 (30) | 5 (3.0) | 34 (20.6) | 0.96 (0.94–0.97) |

Difference = Recalled duration − Recorded duration.

Missing data: three missing for recalled duration of breastfeeding or feeding breast milk, therefore n = 296.

CI, confidence interval; GED, general educational development; IQR, interquartile range; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Appendix Table A4.

Comparison of Recorded and Recalled Duration of Maternal Milk Expression, by Maternal and Child Characteristics (n = 293)

| Characteristics | n | Recorded median (IQR) (days) | Recalled median (IQR) (days) | Median of differences (IQR) | Underestimation error >30 days (%) | Overestimation error >30 days (%) | ICC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | |||||||

| All moms | 293 | 150 (215) | 179 (242) | 0 (49) | 54 (18.4) | 70 (23.9) | 0.83 (0.80–0.87) |

| Age at delivery (years) | |||||||

| ≤30 | 150 | 120 (212) | 151 (223) | 0 (49) | 25 (16.7) | 39 (26.0) | 0.83 (0.77–0.87) |

| >30 | 143 | 176 (224) | 180 (245) | 0 (53) | 29 (20.3) | 31 (21.7) | 0.84 (0.78–0.88) |

| Race | |||||||

| White/Caucasian | 241 | 175 (237) | 180 (231) | 0 (57) | 51 (21.2) | 54 (22.4) | 0.86 (0.82–0.89) |

| Black/African American | 29 | 61 (131) | 80 (180) | 0 (25) | 2 (6.9) | 7 (24.1) | 0.74 (0.55–0.87) |

| Other | 23 | 90 (136) | 121 (260) | 13 (102) | 1 (4.4) | 9 (39.1) | 0.59 (0.32–0.80) |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 14 | 76 (174) | 91 (208) | 4 (86) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (35.7) | 0.80 (0.53–0.92) |

| Non-Hispanic | 279 | 156 (218) | 179 (241) | 0 (51) | 53 (19.0) | 65 (23.3) | 0.83 (0.80–0.87) |

| Education | |||||||

| High school/GED or less | 32 | 30 (134) | 49 (140) | 0 (46) | 6 (18.8) | 6 (18.8) | 0.60 (0.36–0.79) |

| Some college/associate's degree | 44 | 77 (174) | 104 (219) | 1 (46) | 8 (18.2) | 9 (20.5) | 0.78 (0.65–0.88) |

| Bachelor's degree | 113 | 160 (239) | 180 (208) | 2 (52) | 18 (16.0) | 30 (26.6) | 0.81 (0.73–0.86) |

| Postgraduate degree | 104 | 209 (217) | 211 (241) | 0 (56) | 22 (21.2) | 25 (24.0) | 0.89 (0.84–0.92) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Married/living with partner | 264 | 167 (235) | 180 (231) | 0 (53) | 53 (20.1) | 62 (23.5) | 0.84 (0.80–0.87) |

| Unmarried/not living with partner | 29 | 53 (101) | 60 (159) | 2 (32) | 1 (3.5) | 8 (27.6) | 0.71 (0.49–0.85) |

| Parity | |||||||

| Primiparous | 155 | 180 (216) | 204 (226) | 0 (48) | 27 (17.4) | 38 (24.5) | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) |

| Multiparous | 138 | 114 (230) | 121 (240) | 0 (53) | 27 (19.6) | 32 (23.2) | 0.79 (0.72–0.85) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | |||||||

| Yes | 18 | 49 (139) | 60 (179) | 2 (52) | 4 (22.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.78 (0.53–0.90) |

| No | 275 | 160 (235) | 179 (239) | 0 (51) | 50 (18.2) | 65 (23.6) | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) |

| WIC enrollment in pregnancy or infancy | |||||||

| Yes | 70 | 60 (167) | 84 (179) | 3 (41) | 8 (11.4) | 17 (24.3) | 0.77 (0.66–0.85) |

| No | 222 | 178 (215) | 181 (228) | 0 (53) | 45 (20.3) | 53 (23.9) | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) |

| Annual household income <$35,000 | |||||||

| Yes | 78 | 86 (161) | 118 (178) | 2 (49) | 9 (11.5) | 21 (26.9) | 0.72 (0.60–0.81) |

| No | 214 | 178 (234) | 181 (232) | 0 (58) | 45 (21.0) | 49 (22.9) | 0.86 (0.82–0.89) |

| Public or no health insurance | |||||||

| Yes | 45 | 60 (174) | 60 (188) | 0 (27) | 4 (8.9) | 8 (17.8) | 0.82 (0.70–0.89) |

| No | 248 | 171 (219) | 180 (221) | 1 (53) | 50 (20.2) | 62 (25.0) | 0.83 (0.78–0.86) |

| Mom ever went to work/school 20+ hours/week | |||||||

| Yes | 200 | 150 (235) | 178 (217) | 0 (50) | 36 (18.0) | 47 (23.5) | 0.88 (0.85–0.91) |

| No | 93 | 149 (233) | 179 (266) | 3 (48) | 18 (19.4) | 23 (24.7) | 0.74 (0.64–0.82) |

| Child's characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 147 | 144 (227) | 178(221) | 0 (59) | 31 (21.1) | 37 (25.2) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) |

| Female | 146 | 160 (235) | 179 (259) | 1 (46) | 25 (15.8) | 33 (22.6) | 0.88 (0.83–0.91) |

| Birth maturity | |||||||

| Preterm birth | 23 | 120 (213) | 178 (166) | 0 (53) | 1 (4.4) | 4 (17.4) | 0.92 (0.81–0.96) |

| Term birth | 270 | 150 (236) | 179 (244) | 1 (49) | 53 (19.6) | 66 (24.4) | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) |

| Birth weight (kg) | |||||||

| ≤3.3 | 128 | 120 (209) | 166 (218) | 0 (49) | 20 (15.6) | 32 (25.0) | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) |

| >3.3 | 165 | 169 (235) | 180 (248) | 1 (52) | 34 (20.6) | 38 (23.0) | 0.85 (0.80–0.88) |

Difference = Recalled duration − Recorded duration

Missing data: six missing for recalled duration of maternal milk expression, therefore n = 293.

CI, confidence interval; GED, general educational development; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IQR, interquartile range; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Funding Information

The project described was supported by the Grant 1R03SH000048 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Award Number Grant UL1TR002733 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1. Lodge CJ, Tan DJ, Lau MXZ, et al. Breastfeeding and asthma and allergies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:38–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horta BL, Victora CG. Long-term effects of breastfeeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013;74 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yan J, Liu L, Zhu Y, et al. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, Victora CG. Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104(s467):96–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amissah EA, Kancherla V, Ko YA, et al. Validation study of maternal recall on breastfeeding duration 6 years after childbirth. J Hum Lact 2017;33:390–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Natland ST, Andersen LF, Nilsen TI, et al. Maternal recall of breastfeeding duration twenty years after delivery. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tienboon P, Rutishauser IH, Wahlqvist ML. Maternal recall of infant feeding practices after an interval of 14 to 15 years. Aust J Nutr Diet 1994;51:25 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gillespie B, d'Arcy H, Schwartz K, et al. Recall of age of weaning and other breastfeeding variables. Int Breastfeed J 2006;1:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Promislow JH, Gladen BC, Sandler DP. Maternal recall of breastfeeding duration by elderly women. Am J Epidemiol 2005;161:289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burnham L, Buczek M, Braun N, et al. Determining length of breastfeeding exclusivity: validity of maternal report 2 years after birth. J Hum Lact 2014;30:190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agampodi SB, Fernando S, Dharmaratne SD, et al. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding; validity of retrospective assessment at nine months of age. BMC Pediatr 2011;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bland RM, Rollins NC, Solarsh G, et al. Maternal recall of exclusive breast feeding duration. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:778–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Zyl Z, Maslin K, Dean T, et al. The accuracy of dietary recall of infant feeding and food allergen data. J Hum Nutr Diet 2016;29:777–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cupul-Uicab LA, Gladen BC, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Reliability of reported breastfeeding duration among reproductive-aged women from Mexico. Matern Child Nutr 2009;5:125–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barbosa RW, Oliveira AE, Zandonade E, et al. Mothers' memory about breastfeeding and sucking habits in the first months of life for their children. Rev Paul Pediatr 2012;30:180–186 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li R, Scanlon KS, Serdula MK. The validity and reliability of maternal recall of breastfeeding practice. Nutr Rev 2005;63:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Troy LM, Michels KB, Hunter DJ, et al. Self-reported birthweight and history of having been breastfed among younger women: An assessment of validity. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomeo CA, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, et al. Reproducibility and validity of maternal recall of pregnancy-related events. Epidemiology 1999;10:774–777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Labiner-Wolfe J, Fein SB, Shealy KR, et al. Prevalence of breast milk expression and associated factors. Pediatrics 2008;122(Supplement 2):S63–S68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boone KM, Geraghty SR, Keim SA. Feeding at the breast and expressed milk feeding: Associations with otitis media and diarrhea in infants. J Pediatr 2016;174:118–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soto-Ramírez N, Karmaus W, Zhang H, et al. Modes of infant feeding and the occurrence of coughing/wheezing in the first year of life. J Hum Lact 2012;29:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Keim SA, Smith K, Boone KM, et al. Cognitive testing of the Brief Breastfeeding and Milk Expression Recall Survey. Breastfeed Med 2018;13:60–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keim SA, McNamara KA, Dillon CE, et al. Breastmilk sharing: Awareness and participation among women in the Moms2Moms Study. Breastfeed Med 2014;9:398–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Watson PF, Petrie A. Method agreement analysis: A review of correct methodology. Theriogenology 2010;73:1167–1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 2016;15:155–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giavarina D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem Med 2015;25:141–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tate AR, Dezateux C, Cole TJ, et al. ; Millennium Cohort Study Child Health G. Factors affecting a mother's recall of her baby's birth weight. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:688–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keim SA, Smith K, Ingol TI, et al. Improved estimation of breastfeeding rates using a novel breastfeeding and milk expression survey. Breastfeed Med 2019;14:499–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]