Abstract

CCCH-type tandem zinc finger (TZF) domains are found in many RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that regulate the essential processes of post-transcriptional gene expression and splicing through direct protein-RNA interactions. In Caenorhabditis elegans, RBPs control the translation, stability, or localization of maternal messenger RNAs required for patterning decisions before zygotic gene activation. MEX-5 (Muscle EXcess) is a C. elegans protein that leads a cascade of RBP localization events that is essential for axis polarization and germline differentiation after fertilization. Here, we report that at room temperature, the CCCH-type TZF domain of MEX-5 contains an unstructured zinc finger that folds upon binding of its RNA target. We have characterized the structure and dynamics of the TZF domain of MEX-5 and designed a variant MEX-5 in which both fingers are fully folded in the absence of RNA. Within the thermal range experienced by C. elegans, the population of the unfolded state of the TZF domain of MEX-5 varies. We observe that the TZF domain becomes less disordered at lower temperatures and more disordered at higher temperatures. However, in the temperature range in which C. elegans is fertile, when MEX-5 needs to be functional, only one of the two zinc fingers is folded.

Significance

RNA-binding proteins are important during embryogenesis, when they regulate messenger RNAs passed from mother to child through the oocyte. Errors in this regulation may lead to embryonic lethality and/or birth defects. This study is focused on MEX-5 (Muscle EXcess), an RNA-binding protein that controls the earliest stages of embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans through an unknown mechanism. To understand its function, we characterize the structure of the RNA-binding domain of MEX-5 in solution and determined how primary sequence modulates structure and stability. The RNA-binding domain of MEX-5 is partially disordered but folds upon RNA binding. This domain is tuned to be partially disordered only over the temperature range in which C. elegans is fertile and MEX-5 needs to be functional.

Introduction

During embryogenesis, a fertilized oocyte develops from a single cell, the zygote, into a multicellular organism. Before zygotic transcription begins, the restricted distribution of maternal factors and their regulation coordinate the early developmental processes (1,2). These maternal factors include quiescent messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and proteins present in the oocyte cytoplasm. The Caenorhabditis elegans zygote is a classic model for the study of intracellular asymmetries (3,4) in which conserved mechanisms of cell polarization and cytoplasmic organization have been elucidated (5). After fertilization, polarization of the C. elegans zygote along the anterior-posterior embryonic axis occurs through the action of several conserved polarity regulators, the maternal PAR proteins, which localize to the anterior (PAR-6, PAR-3, and PKC-3) or posterior (PAR-2 and PAR-1) cell cortex (6). As a response to this asymmetry, other cell-fate determinants become asymmetrically distributed in the cytoplasm. Among these cell-fate determinants is the CCCH-type tandem zinc finger (TZF) RNA-binding protein MEX-5 (Muscle EXcess), which redistributes across the length of the 50-μm zygote with a concentration gradient anterior high to posterior low in a time span of ∼10 min (7,8). Such anterior enrichment of MEX-5 is driven by a phosphogradient (9, 10, 11): phosphorylation of MEX-5 by the kinase PAR-1 results in increased MEX-5 diffusion in the posterior, whereas in the anterior, the phosphatase PP2A reverts MEX-5 to an unphosphorylated and slow-diffusing state (11). The spatial asymmetry in the generation of the phosphorylated forms of MEX-5 generates a diffusion gradient that causes the protein to concentrate in the region of low diffusivity (5). Subsequently, MEX-5 accumulation in the anterior leads to partitioning of other proteins such as PIE-1 and POS-1 to the posterior cytoplasm and PLK-1 to the anterior cytoplasm (7,12, 13, 14). The first stages of C. elegans development feature a series of rapid and invariant asymmetric cell divisions that determine the identity of the early embryonic blastomeres (5). As a consequence of proper anterior-posterior polarity, the zygote divides unequally, yielding the larger anterior cell AB and the smaller posterior cell P1. Consequently, during the first cell division, the two daughter blastomeres inherit different determinants, which specify their distinct fates (anterior/somatic and posterior/germline).

MEX-5 (UniProtKB: Q9XUB2) was first identified by Schubert et al. in a genetic screen for maternal effect lethal mutants (7). Schubert et al. (7) observed that adults homozygous for null mutations in the mex-5 gene produced embryos containing abnormally large numbers of muscles toward their anterior poles. These embryos were unable to undergo body morphogenesis and died without hatching. In 2007, Pagano et al. characterized MEX-5 RNA-binding specificity and showed that the protein binds to poly-U-rich sequences that are abundant in C. elegans 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) (15). According to these results, it has been proposed (15) that MEX-5 may function, in the two-cell stage and during further cell division, as a broad-spectrum RNA-binding protein to activate maternal mRNA turnover in the AB blastomere and in the somatic lineage cells (16). More recently, Han et al. (17) have proposed a mechanism to explain the repulsive coupling between MEX-5 and POS-1 in the zygote, which is similar in many respects to that for MEX-5 segregation: the polo-like kinase (PLK)-1 interacts with MEX-5, distributed along an anterior-rich cytoplasmic gradient, and is recruited into slow-diffusing complexes; in the anterior cytoplasm, PLK-1, in turn, phosphorylates POS-1 and inhibits the formation of stable, slow-diffusing POS-1/RNA complexes (17).

In addition to its role in the establishment of the body axis in the early stages of embryogenesis, MEX-5 has been shown to be essential for the spatial patterning of the P granules, ribonucleoprotein organelles found in the germline cytoplasm (18, 19, 20). P granule proteins form germ granules by phase transition, and this process is mediated by RNA binding. MEX-5 competes with the P granule proteins MEG-3 and PGL-3 for access to RNA and therefore suppresses the assembly of MEG-3 and PGL-3 into phase-separated liquid droplets in the anterior. To date, a comprehensive understanding of MEX-5 functions in vivo has not been yet elucidated, however.

The mex-5 gene encodes for a 468-amino acid (aa) protein with predicted low-complexity N- and C-terminal regions flanking a central RNA-binding domain. The N-terminal region is rich in polyglutamine stretches that could mediate MEX-5 self-association (11). The RNA-binding domain of MEX-5, residues 268–341 (see Fig. 1), has high sequence homology to the CCCH-type TZF motif that was first described in the vertebrate protein tristetraprolin (TTP), an RNA-binding protein that regulates mRNA stability (21, 22, 23). In TTP, each zinc finger (ZF) coordinates a zinc ion by means of three cysteine residues and one histidine (Fig. 1). Although several studies have characterized the RNA-binding specificity of MEX-5, insights into the structure of the TZF domain of MEX-5 are necessary to shine light onto the RNA-binding mechanisms and their contribution to the protein activity during the early stages of embryogenesis.

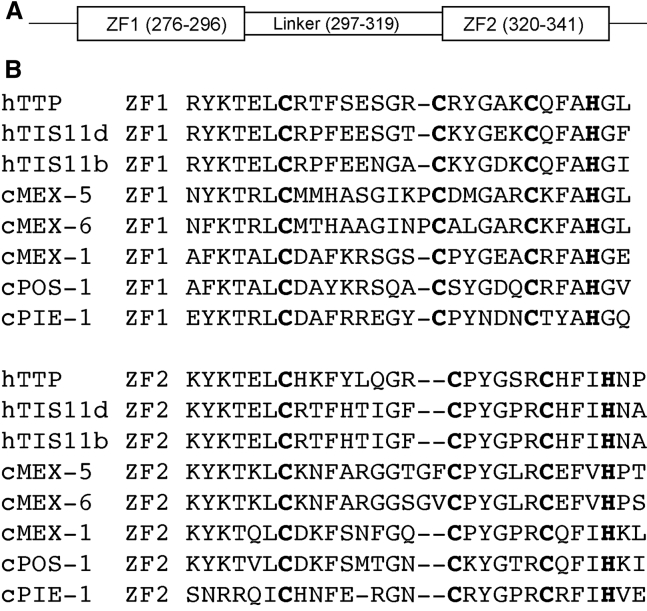

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of CCCH-type zinc fingers. (A) A schematic representation of the RNA-binding domain of MEX-5, also known as tandem zinc finger (TZF) domain, is shown. (B) Sequence alignment of CCCH-type zinc fingers in human (h) and C. elegans (c) is shown. The zinc-coordinating residues are highlighted in bold font.

In this study, we present the first structural characterization, to our knowledge, of the TZF domain of MEX-5. We show that in the range of temperatures in which C. elegans is fertile (between 9 and 25°C (24)), only the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5 is always folded, whereas the N-terminal zinc finger is unstructured and does not bind Zn2+ but folds and stably binds Zn2+ when binding RNA. We identified the structural elements that differ between the N- and C-terminal zinc fingers and that affect the Zn2+ binding affinity and thermodynamic stability of the zinc fingers. Finally, to validate our findings, we engineered a mutant variant of MEX-5 in which both zinc fingers are folded in the absence of RNA and that binds RNA with similar affinity as the wild-type protein.

Material and Methods

Protein expression

The RNA-binding domains of human MEX-5 (residues 268–346) and MEX-5312–346 were amplified from pMal-MEX-5 (15) and cloned into a modified pet28 vector with a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) tag between BamH1 restriction site. This vector was designed to include a 6xHis tag at the N-terminal, followed by the sequence encoding for SUMO and a BamH1 restriction site engineered for cloning of the fragment of interest. MEX-5CX10C was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and cloned into the same vector. Mutations described in Table 2 were generated via site-directed mutagenesis. MEX-5 and its variants were expressed within BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli-competent cells. Isotopic labeling with 15N and/or 13C was performed by growing the cells in M9 containing 1 g of 15NH4Cl per liter and 2 g of 13C glucose per liter, respectively. The cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.8 and then induced for 4 h with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1 thiogalactopyranoside and 0.1 mM ZnSO4 at the same temperature. Harvested cells were lysed using a cell disruptor in 50 mL buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 1 EDTA-free cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Tablet (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Lysates were centrifuged at 19,500 rotations per minute for 1 h at 4°C and passed through a 20-mL prepacked HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL); washed with five column volumes of 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole; and eluted with 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 350 mM imidazole. The SUMO tag was cleaved off with ULP1. The cleavage reaction was performed overnight at room temperature, using a ULP1/protein ratio of 1:10. The protein was then passed through sequential 5-mL HiTRAP Q and SP columns (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Marlborough, MA) pre-equilibrated with a buffer containing 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.0) and 50 mM NaCl. Purified protein solution was buffer exchanged into 50 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 6.2), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and 0.1 mM ZnSO4 by dialysis and concentrated to 250 μM for NMR spectroscopy experiments using a 3-kDa Centriprep concentrator (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA). All the experiments were performed using freshly prepared samples to prevent cysteine oxidation and protein degradation.

Table 2.

Mutations in ZF1 of MEX-5, within Cys276 and Cys286, that Mimic the Sequence of the Corresponding Fragment of ZF2

| MEX-5 Variant | Amino Acid Sequence between C276 and C286 |

|---|---|

| MEX-5 | CMMHASG-IKPC |

| Mutant A | CMMFASG-IKPC |

| Mutant B | CMMHASG-IKAC |

| Mutant C | CMMHASGGIKPC |

| Mutant D | CMMHASGAIKPC |

| Mutant E | CMMHASGGIGPC |

| Mutant F | CMMHASGGTGPC |

| Mutant G | CMNHASGGIKPC |

| Mutant H | CMNHASGGIGPC |

| MEX-5CX10C | CKNFARGGTGFCa |

Mutated residues are underlined.

This is the same sequence as in ZF2 (i.e. between C320 and C331).

NMR spectroscopy

Folding of MEX-5 and its variants was monitored via NMR spectroscopy. 15N-1H heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra were collected at 293 K on a Varian Inova spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA) operating at 600 MHz equipped with a triple-resonance cold probe. Data processing was performed using NMRPipe (25) and Sparky (26) software.

Triple-resonance spectra were collected at 600 MHz on 13C, 15N-labeled protein in 92% H2O/8% 2H2O. Complete protein backbone 1H, 13C, and 15N resonance assignments for MEX-5312–346 were made using HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HN(CA)CO, and HNCO. Aliphatic side-chain assignments were made using hCCH-TOCSY, HCcH-TOCSY, and HCcH-COSY experiments. Assignments for aromatic side chains were made from (H β)Cβ(CγCδ)Hδ and (Hβ)Cβ(CγCδCε)Hε spectra. A 15N-edited NOESY spectrum and a 13C-edited NOESY spectrum were acquired in 92% H2O/8% 2H2O with a mixing time of 300 ms. The chemical shift data have been submitted to the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank under accession number BMRB: 30623.

All backbone 15N relaxation rates, R1 and R2, and 1H-15N heteronuclear nuclear Overhauser enhancements (hetNOEs), were collected for uniformly 15N-labeled MEX-5312–346 in 50 mM MES (pH 6.2), 100 mM NaCl, 100 μM ZnOAc, and 100 μM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine on a 600 MHz Varian instrument (Palo Alto, CA) at 293 K. Time delays of 11.1 (× 2), 55.5 (× 2), 111, 222, 444, 666, and 832 ms were used for R1, and 6, 9 (× 2), 21, 39, 60 (× 2), 90, 120, 150, 180, and 210 ms were used for R2 measurements. The errors for each set were estimated based on the duplicate measurements. hetNOEs were calculated from the ratio of peak intensities of 1H-15N crosspeaks with and without proton saturation pulse, and the error for each spectrum was estimated from the noise. For relaxation-dispersion analysis, relaxation-compensated, constant-time Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) experiments (27,28) were collected at 293 K at a static magnetic field of 14.1 T with a constant relaxation time of 40 ms and values of τcp (milliseconds) of 0.714, 1 (× 2), 1.25, 1.67, 2, 2.5, 3.33, 5 (× 2), and 10, where τcp is the delay between 180° pulses in the CPMG pulse train.

Structure calculations

Intramolecular protein distance restraints were derived from 13C-edited and 15N-edited NOESY spectra. Ambiguous distance restraints for the ZF domain and torsional restraints were generated in CYANA 2.1 (29), and the same software was used to determine initial MEX-5312–346 structures. Dihedral-angle restraints were based primarily on 3J HNHα coupling constants from HNHA data (ϕ = 20 ± 45° if 3J HNHα > 7.5 Hz; ϕ = 50 ± 45° if 3 3J HNHα < 6.0 Hz). Additional ϕ and ψ restraints were assigned using TALOS (30), only in cases in which those restraints were unambiguous and consistent with the directly determined ϕ restraints. The 20 lowest-energy structures generated in CYANA were further refined using simulated annealing with the constraints described above to obtain the final ensemble of structures. All restrained simulated annealing was done in CNS (31,32). During all calculations, the zinc coordination was restrained to be tetrahedral. Quality of the structures was assessed using PSVS1.4 (33) and RPF (34) analysis; see Table 1. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB: 6PMG).

Table 1.

Summary of NMR and Structural Statistics for C. elegans MEX-5 ZF2

| Conformationally Restricting Constraintsa | |

|---|---|

| NOE-based distance constraints: | |

| Total | 303 |

| intraresidue [i = j] | 96 |

| sequential [|i − j| = 1] | 111 |

| medium range [1 < | i − j| < 5] | 40 |

| long-range [|i − j| ≥ 5] | 53 |

| NOE constraints per restrained residue | 9.2 |

| Dihedral-angle constraints | 43 |

| Total number of restricting constraints | 346 |

| Total number of restricting constraints per restrained residue | 10.5 |

| Restricting long-range constraints per restrained residue | 1.6 |

| Residual Constraint Violationsa | |

| Average number of distance violations per structure: | |

| 0.1–0.2 Å | 3.5 |

| 0.2–0.5 Å | 1.1 |

| >0.5 Å | 0 |

| Average RMS of distance violation/constraint | 0.05 Å |

| Maximal distance violation | 0.31 Å |

| Average number of dihedral-angle violations per structure: | |

| 1–10° | 3.65 |

| >10° | 0 |

| RMS of dihedral-angle violation/constraint | 1.14° |

| Maximal dihedral-angle violation | 7.90° |

| RMSD from Average Coordinatesa,b | |

| Backbone atoms | 1.9 Å |

| Heavy atoms | 2.7 Å |

| Ramachandran Statistics for Ordered Residues (MolProbity)a,b | |

| Most favored regions | 98.8% |

| Allowed regions | 1.2% |

| Disallowed regions | 0% |

| Global Quality Scoresa | Raw/Z-Score |

| Procheck G-factor (ϕ/ψ only)b | −0.24/−0.63 |

| Procheck G-factor (all dihedral angles)b | −0.13/−0.77 |

| Verify3D | 0.20/−4.17 |

| ProsaII | 0.13/−2.15 |

| MolProbity clash | 12.43/−0.61 |

Structural statistics were computed for the ensemble of 20 structures.

Summary of NMR and structural statistics generated using PSVS 1.5 (3). Average distance violations were calculated using the sum over r−6.

Values calculated over residues 320–341, between the first and last Zn+2-coordinating residues.

MEX-5 RNA-binding domain homology model building and preparation

The structure of the ligand-free RNA-binding domain of MEX-5 (residues 268–346) was generated starting from the lowest-energy NMR structure of TIS11d (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 1RGO) bound to an adenylate-uridylate-rich element (ARE) (5′-UUAUUUAUU-3′) using the SWISS-MODEL server (35, 36, 37). The resulting structure was solvated using VMD 1.9.2 (38) in an orthorhombic water box (60 × 75 × 66 Å). Six Cl− ions were added to the system to neutralize the charge.

Simulation protocol

The solvated protein, described above, was energy minimized and equilibrated using the NAMD 2.10 molecular modeling package (39) and the CHARMM27 force field (40). The force field was modified after Sakharov and Lim (41) to include polarization and charge transfer effects for the Zn2+ ions and the side chain atoms of the zinc-coordinating residues. Before equilibration, the system was subjected to energy minimization in three stages, with restraints sequentially removed: first, all heavy atoms were constrained; next, only Cα atoms were constrained; and finally, minimization was done without constraints. The system was subsequently subjected to stepwise heating during constant volume molecular dynamics (MD) with restraints applied to Cα atoms, followed by 10 ps of unconstrained constant-NPT MD equilibration at 1 atm and 298 K. Trajectories were subsequently collected from constant-NPT MD simulations at 1 atm and 298 K. Temperature and pressure were maintained using Langevin dynamics (damping coefficient: 5 ps−1) and the Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston method, respectively. The equations of motion were integrated using the SHAKE constraint algorithm to use a 2-fs time step (42). Nonbonded interactions were calculated at every time step, with a cutoff distance of 12 Å and a switching distance of 10 Å. The particle mesh Ewald method was used to treat electrostatic interactions with periodic boundary conditions (43,44). Three trajectories of MEX-5 were run, each for a total of 50 ns. Trajectories were analyzed using VMD 1.9.2 (38), and molecular configurations were visualized using STRIDE (45) and Tachyon (46).

To determine whether the zinc-coordinating histidine residue is sampling more than one rotameric state, we calculated the angle and the distance between the stacked aromatic side chains, His279 and His296 in ZF1 and for Phe323 and His341 in ZF2, respectively. The stacking angle was calculated as the angle between the normals of the two aromatic rings (the planes for the side chains are defined by atoms , , and for histidine and Cζ, , and for phenylalanine). The distance between the aromatic rings was calculated as the distance between the centers of mass for the heavy atoms of the two side chains.

Measurements of RNA-binding affinity

The RNA-binding activity of the TZF fragment of MEX-5 and its variant MEX-5CX10C were determined using fluorescent electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) with fluorescein end-labeled RNA as previously described (15,47). Briefly, the affinities of the peptides for the RNA sequences described in Fig. S13 were measured by direct titration of 3 nM labeled RNA with increasing concentrations of protein. Varying concentrations of the protein were incubated for 3 h at room temperature with 3 nM fluorescently labeled RNA in a buffer solution containing 10 mM TRIS (pH 8), 100 μM Zn(OAc)2, 100 mM KCl, 0.01 mg transfer RNA, 0.01% (v/v) octylphenoxypoly(ethyleneoxy)ethanol (IGEPAL), and 2 mM dithiothreitol. Samples were loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel in TB (TRIS-borate) buffer and run for 60 min at 120 V at 4°C to separate bound from free RNA. To detect the fluorescently labeled RNA, the gel was imaged using a Fluoro Image Analyzer Fuji FLA-5000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The fluorescence intensity of bound and unbound RNA were determined as a function of protein concentration using ImageJ (48,49). The data were fitted to a quadratic equation to determine the apparent equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd,app):

| (1) |

where ϕ is the fraction of bound RNA, P is the total protein concentration, R is labeled nucleic acid concentration, and b and m are the base and maximal signals.

To determine the temperature dependence of the RNA-binding affinity of MEX-5, we used fluorescence polarization measurements as previously described (15,50). In these experiments, the TZF domain of MEX5 was expressed as a C-terminal fusion to the maltose-binding protein (MBP): MBP-MEX-5. Comparison of the RNA-binding affinity, measured using EMSA, of the isolated TZF domain of MEX-5 with that of MBP-MEX-5 (15) shows that the MBP tag does not perturb the RNA-binding affinity of the TZF domain of MEX-5. Briefly, the affinity of MBP-MEX-5 for the fluorescein end-labeled 5′-UUUUAUUUAUUUU-3′ RNA oligonucleotide (ARE13) was measured at different temperatures by direct titration of 3 nM labeled RNA with increasing concentrations of protein. Equilibration reactions at varying concentration of MBP-MEX-5 were prepared using the same conditions as the electrophoretic mobility shift experiments above in 96-well black plates. The apparent fluorescence polarization was determined using a VictorX5 Plate Reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) equipped with fluorescein-sensitive filters and polarizers. A total of three reads were measured for each experiment, and the average and standard deviation of the millipolarization value (mP) were calculated for each protein concentration. The data were fitted at each temperature using Eq. 1 to obtain Kd,app constants as a function of the temperature. To characterize the thermodynamics of binding, the association constants, Ka,app = 1/Kd,app, were fitted as a function of the temperature using the following equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Equations 2 and 3 describe how Ka,app varies as a function of temperature in terms of the change in enthalpy, entropy, and heat capacity (ΔH, ΔS, ΔCp) of binding at the reference temperature, Tref. In Eq. 2, ΔH and ΔS are constant, whereas in Eq. 3, both ΔH and ΔS vary with temperature as determined by ΔCp.

Results

In the RNA-free state, only the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5 is folded

As a first step in the characterization of the structure and dynamics of the TZF domain of MEX-5, we collected and assigned the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the RNA-binding domain of MEX-5, comprising residues 268–346 (MEX-5268–346), in the RNA-free form. Dispersion of the chemical shifts and analysis of the crosspeak linewidths observed in the HSQC spectrum provide preliminary structural information such as the presence of folded or unfolded regions (51). Most of the 1H-15N crosspeaks for residues in the linker and in the C-terminal zinc finger (ZF2) could be assigned (Fig. 2 A). However, we observed that crosspeaks corresponding to residues in the N-terminal zinc finger (ZF1) were very low in intensity or broadened beyond detection. A similar result has been observed for the CCCH-type TZF domain of the human protein TTP (47,52). For TTP, the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum shows only crosspeaks corresponding to its N-terminal zinc finger, whereas the peaks corresponding to the C-terminal zinc finger are broadened beyond detection. In the case of TTP, it has been shown that this behavior is due to the C-terminal zinc finger being unstructured when the protein is not bound to RNA (47,52). In the RNA-free form, in fact, the C-terminal zinc finger of TTP is not able to stably coordinate a zinc ion and therefore is in a molten globule state, sampling several partially disordered conformations in the intermediate exchange regime (53). This behavior is different from what was observed for TIS11d, another member of the TTP family of proteins, in which both zinc fingers are folded and stably coordinate a zinc ion in the RNA-free form (54).

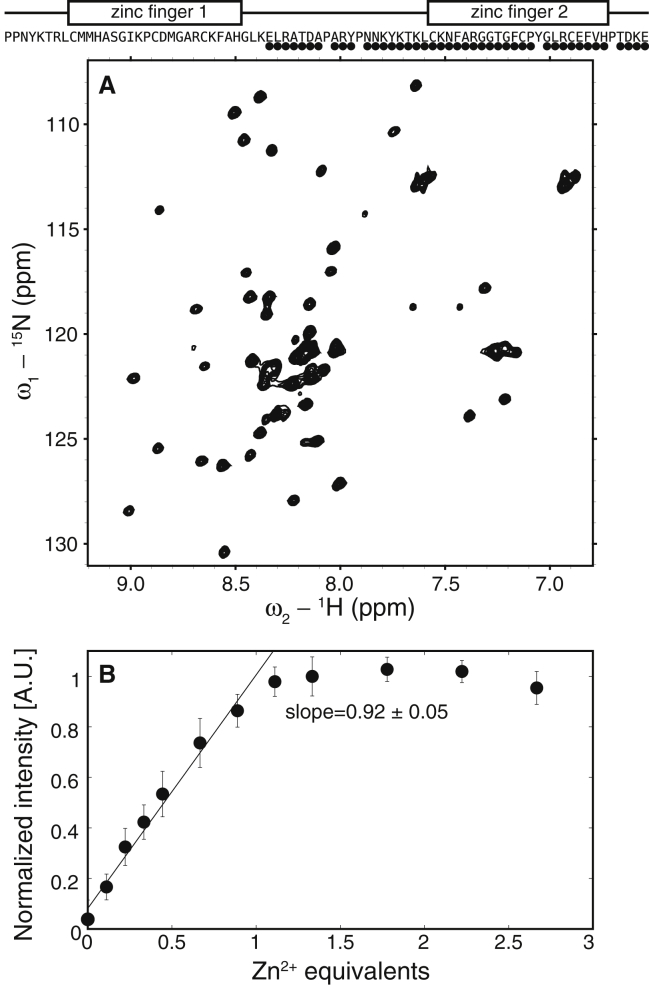

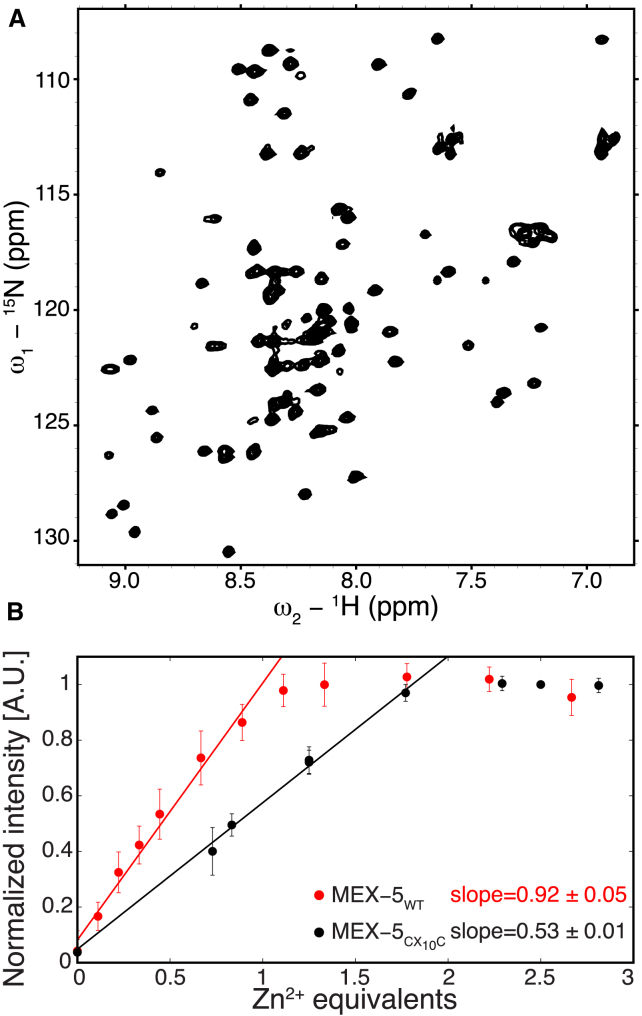

Figure 2.

The TZF domain of MEX-5 is partially unstructured in the RNA-free state. Above the panels, a schematic representation of the TZF domain depicts the ZFs as rectangles and the linker region as a line. The circles indicate residues along the primary sequence with an assigned crosspeak in the 15N-1H HSQC spectrum. (A) The 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of MEX-5 TZF domain is missing all crosspeaks from ZF1 and part of the linker. (B) Zn2+ titration of the TZF domain of MEX-5, monitored by NMR spectroscopy, is shown. Average crosspeak intensities from the 15N-1H HSQC spectra are shown as a function of zinc equivalents added to the protein, errors are estimated from the standard deviation. A linear regression is applied to the first part of the curve, and the resulting slope is shown in the plot.

To investigate the origin of the linewidth broadening of the crosspeaks corresponding to ZF1 in MEX-5, we measured the zinc-binding stoichiometry of the TZF domain of MEX-5. Starting from the unfolded TZF of MEX-5 in the absence of Zn2+, we collected a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra at increasing concentration of zinc ions, and we observed that the end-point of the titration curve occurred at one equivalent of zinc (Fig. 2 B). In light of these results, we concluded that in a similar manner to TTP, the TZF domain of MEX-5 is also partially unstructured in the RNA-free form because the N-terminal zinc finger does not stably bind Zn2+. Prediction of disorder in MEX-5, performed using PONDR (Predictor Of Naturally Disordered Regions (http://www.pondr.com) (55, 56, 57), is in agreement with our experimental findings. Two of the three PONDR predictors (VL3 (58) and VSL2 (59)) assigned different order scores to the residues in the two zinc fingers of MEX-5, indicating that the N-terminal zinc finger has a higher degree of disorder compared with the C-terminal one (see Fig. S1). The other predictor, VLXT (60), produced a similar score for the two zinc fingers (see Fig. S1). This discrepancy among the different predictors might be explained by noting that each predictor is most accurate in detecting disorder in different sequence contexts. The VL3 and VSL2 predictors provide accurate respective evaluations of long and short disordered regions. VLXT is a general disorder predictor that has been reported to underestimate the occurrence of long disordered regions when hydrophobic segments with a propensity to order are present, including potential binding sites like ZF1 (61,62).

In addition, we expressed and purified a shorter construct of MEX-5 containing only the C-terminal zinc finger (residues 312–346), MEX-5312–346 (Fig. S2). Comparison of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the MEX-5268–346 (the full TZF domain) and the MEX-5312–346 (only ZF2) constructs confirmed that the observed crosspeaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of MEX-5268–346 correspond exclusively to residues in ZF2. All the crosspeaks corresponding to ZF2 are present in both spectra, with negligible differences in chemical shifts (Fig. S3). This result indicates that in both constructs, the C-terminal zinc finger assumes the same three-dimensional structure, and thus, that the peptide fragment corresponding to residues 312–346 (ZF2) can independently fold and coordinate a zinc ion.

Both MEX-5 zinc fingers fold upon addition of zinc and RNA

Once we established that the N-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5 is unfolded, we investigated how RNA-binding affects the structure of the TZF domain of MEX-5. The only available three-dimensional structure for a CCCH-type TZF protein is the structure of the TZF domain of the human protein TIS11d in complex with a nonameric RNA (54). TIS11d is a member of the TTP family of proteins that regulates the stability of transcripts containing AREs in their 3′-UTR, described above (21, 22, 23). The solution structure of TIS11d in complex with its cognate RNA was determined using NMR spectroscopy and shows that each zinc finger of TIS11d recognizes and binds a UAUU motif (54). Other biochemical studies of the RNA-binding activity of CCCH-type TZF proteins (15,47,63,64) have confirmed that their minimal consensus sequence is a single-strand RNA oligonucleotide spanning eight nucleotides in length, supporting the hypothesis that each zinc finger recognizes a four-nucleotide motif. For MEX-5, it has been shown that the TZF domain binds with submicromolar affinity to any uridine-rich sequence containing six to eight uridines within an eight-nucleotide window (15). The same study also reported that MEX-5 recognizes with high affinity one of the RNA targets of the human homolog proteins TTP and TIS11d, the ARE located in the 3′-UTR of the tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) mRNA (15).

Here, we used the RNA oligonucleotide with sequence 5′-UUUUAUUUAUUUU-3′ (ARE13) from the 3′-UTR of TNF-α transcript as a binding partner of the TZF domain MEX-5268–346. This sequence contains the two UAUU repeats, each recognized by a zinc finger in TIS11d (54). The apparent dissociation constant of MEX-5268–346 for this sequence, measured using EMSA, is Kd,app = 16 ± 1 nM. To evaluate the structural changes in the TZF of MEX-5 upon addition of RNA, we acquired a 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of the protein in complex with the ARE13 RNA oligonucleotide (see Fig. S5). We observed an increased number of crosspeaks in the spectrum of the bound state (66 crosspeaks for a total of 72 nonproline residues) compared to the RNA-free state (43 crosspeaks). In addition, the chemical shifts of the crosspeaks in the bound state are significantly dispersed in the 1H dimension and deviate from the values of residues in a random coil conformation. The increased number of crosspeaks and their increased chemical shift dispersion indicate that upon RNA binding, the N-terminal zinc finger undergoes a conformational transition from a molten globule state to a folded state; therefore, both the zinc fingers in the TZF domain of MEX-5 become folded and stably coordinate a zinc ion.

The NMR solution structure of the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5

The primary sequence of the TZF domain of MEX-5 is characterized by unique features among the CCCH-type TZF protein family. The spacing between the cysteine and histidine zinc-coordinating residues, Cys-X8-Cys-X5-Cys-X3-H (where X is any residue), is invariant in the human proteins of the TTP family and in many C. elegans homologs (see Fig. 1). In MEX-5, however, the spacing between the first and second cysteine residues is increased in both zinc fingers: Cys-X9-Cys-X5-Cys-X3-H in ZF1 and Cys-X10-Cys-X5-Cys-X3-H in ZF2, respectively. The different spacing and the relatively low sequence homology with the human proteins TIS11d and TTP suggest that the structure of the zinc fingers in MEX-5 may be different from the known structure of TIS11d and from that of the other members of the protein family.

Structure determination was challenging using the MEX-5268–346 construct because of the partially unstructured nature of the domain. With the N-terminal zinc finger partially unfolded, more than half of the residues in the TZF domain (ZF1 and the linker) are in a molten globule conformation, with the corresponding crosspeaks having similar resonances or being broadened beyond detection. As a result, the spectra displayed crowded regions that made the assignment of the resonances infeasible. To overcome these difficulties, we collected all the NMR experiments with the MEX-5312–346 construct, which included only the structured C-terminal zinc finger. As discussed above, the structure of the isolated C-terminal zinc finger is not different from that of the zinc finger in the TZF domain (Fig. S3). For the MEX-5312–346 construct, all the observed crosspeaks in the 1H, 13C, and 15N triple-resonance and NOESY spectra were also observed in the corresponding spectra collected for the longer construct, MEX-5268–346.

The resulting ensemble of structures (root mean-square deviation = 0.6 Å for N, Cα, C′, and O atoms in the ordered region 320–341) (see Fig. 3 A; Table 1) shows that binding of the zinc ion is required to stabilize the structure of the finger and occurs through the side chains of Cys320, Cys331, Cys337, and His341 (see Fig. S4). The histidine residue coordinates the zinc via its Nε2 atom. The protein structure is further stabilized by hydrogen bonds from main chain amide groups to the sulfur atom of Cys337 and by long-range backbone hydrogen bonds (see Fig. 3 B). In addition, the conserved aromatic side chain of Phe323 is stacked against the side chain of His341, indicating that a van der Waals interaction between the phenylalanine and histidine side chains stabilizes the histidine residue in a rotameric state compatible with the zinc-coordination geometry, as was observed in TTP and TIS11d (65).

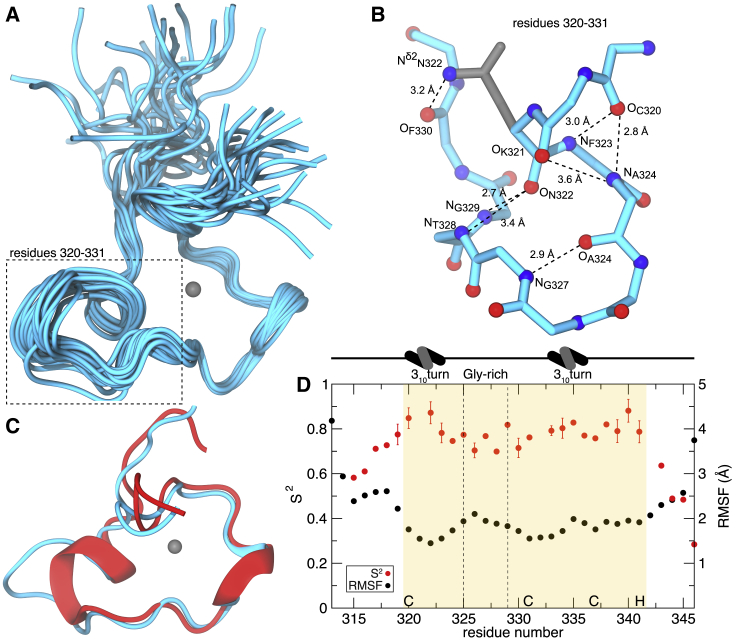

Figure 3.

The solution structure of MEX-5 ZF2. (A) The best 20 structures superimposed on backbone heavy atoms in ordered regions of the protein are shown. The zinc cation is represented as a gray sphere. (B) Hydrogen bonding within the Cys320-Cys331 region of MEX-5 ZF2 is shown. The backbone structure is depicted in cyan, oxygen atoms in red, nitrogen atoms in blue, and the side chain of Asn322 in gray. The atoms forming H-bonds are indicated in the figure. (C) A comparison of the backbone structure between TIS11d ZF2 and MEX-5 ZF2 is given. The lowest-energy structures of the ZF2 of TIS11d (red) and MEX-5 (cyan) are shown superimposed. Zinc is represented as a gray sphere. The α-helices are represented as ribbons. (D) The measure of the backbone flexibility within MEX-5 ZF2 is shown. S2 order parameters are depicted for each residue in red (bars represent the errors of the fit), and the root mean-square fluctuation within the best 20 structures are in black. The zinc finger is highlighted in the yellow box, and the Zn2+ coordinating residues, CCCH, are indicated on the x axis. The glycine-rich loop is highlighted by two dotted lines, and 310 turns are indicated at the top. To see this figure in color, go online.

The polypeptide backbone adopts little regular secondary structure. Within the zinc finger, there are two short 310-helix turns: Cys320 to Ala324, immediately after the first cysteine residue (Cys1) (Fig. 3 B); and Tyr333 to Cys337, immediately before the third cysteine residue (Cys3). The conformation of the zinc finger (residues 320–341) is well defined and relatively rigid in the refined ensemble of structures, with the exception of the flexible glycine-rich loop located between Cys1 and Cys2 (the second zinc-coordinating Cys), specifically residues Arg325, Gly326, Gly327, Thr328, and Gly329, as indicated by the higher root mean-square fluctuation values than the remaining of the domain (see Fig. 3 D). Further evidence of the high flexibility of the glycine-rich loop comes from the low values of the generalized order parameter S2 for these residues (Fig. 3 D) derived from the model-free analysis of the relaxation data (66). Comparing the C-terminal zinc fingers of MEX-5 and TIS11d, we observed a remarkable high similarity of the two backbone structures, with the exception of the region between Cys1 and Cys2 (see Fig. 3 C). In TIS11d, this region contains a six-residue-long α-helix starting at Cys1, whereas in MEX-5, there is a 310 turn from Cys320 to Ala324. The flexible glycine-rich loop follows the 310 turn, allowing the two ends of the loop to come in close proximity through the formation of hydrogen bonds between Asn322 at the N-terminus and Thr328, Gly329, and Phe330 at the C-terminus; the backbone carbonyl group of Asn322 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide group of Gly329 and the backbone amide group of Thr328, and the side chain amide group of Asn322 forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl group of Phe330 (see Fig. 3 B).

Internal motion in the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5

To characterize the internal dynamics of the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5, we determined the dynamic properties of the backbone amide moieties at multiple timescales (picosecond to nanosecond and microsecond to millisecond) using NMR 15N spin-relaxation experiments. We measured NMR 15N longitudinal (R1) and transverse (R2) relaxation rate constants and 1H-15N hetNOE. From these data, using the Lipari and Szabo model-free analysis (66,67), we derived parameters describing amplitudes (S2) and timescales (τe) of the backbone dynamics occurring in the picosecond-to-nanosecond timescale (see Fig. 3 D). An isotropic diffusion model was appropriate to characterize the overall tumbling motion with a τm = 2.4 ns. Out of the 29 residues of zinc finger 2 that were successfully analyzed, 15 were fitted to a motional model characterized by three parameters—S2, τe, and Rex—and the rest to a simpler model characterized by S2 and Rex. The presence of a chemical exchange contribution, Rex, to the transverse relaxation rate constant, R2, indicates that the residues in ZF2 undergo conformational fluctuations on the microsecond-to-millisecond timescale. Using CPMG relaxation dispersion experiments (27), we confirmed that these residues are indeed sampling conformational transitions in the microsecond-to-millisecond timescale (see Fig. S6).

Analysis of the order parameters, S2, describing the amplitude of the backbone motion on the picosecond-to-nanosecond timescale, shows that ZF2 is relatively dynamic in the picosecond-to-nanosecond timescale (see Fig. 3 D). This flexibility is not surprising because of the few secondary structural elements that characterize the structure of ZF2. The residues with the most restricted motions are those located in the 310 turns and between the third and fourth zinc-coordinating residues because they form hydrogen bonds that stabilize either the formation of the 310 turns or that bring the N- and C-terminal ends of ZF2 together, i.e., Val340 HN-Lys318 O. The stability of these hydrogen bonds was recapitulated using all-atom MD simulations, discussed in greater detail below (see Fig. S10 C). Apart from the N- and C-terminal tails, the most flexible region of ZF2 is the glycine-rich loop, as discussed above (see Fig. 3 D). The higher value of S2 measured for Gly329 is due to the formation of a hydrogen bond with N322, shown in Fig. 3 B.

The stacking between His and Phe aromatic rings stabilizes Zn2+ coordination in ZF2

To evaluate the structural differences between the two zinc fingers of MEX-5 that determine their different affinities to zinc ions, we used MD simulations. The initial structure of MEX-5 was built using homology modeling (35, 36, 37) from the solution structure of TIS11d solved by Hudson et al. (54). For this reason, the initial structure of MEX-5 in the MD simulations has both zinc fingers folded and coordinating Zn2+ ions. As discussed above, however, we demonstrated experimentally that only ZF2 of MEX-5 can stably bind Zn2+ in the RNA-free state. Consistent with this finding, Zn2+-coordination at ZF1 is lost in each of the three independent replicate MD trajectories that were collected for MEX-5 in the RNA-free state. In addition, the equilibrated structure of ZF2 converged to the same structure that we determined using NMR spectroscopy (Fig. S7).

We have previously shown that in TTP and TIS11d, the stacking interaction between the zinc-coordinating histidine and a conserved aromatic amino acid, three positions after the first zinc-coordinating cysteine, is crucial to maintain the imidazole ring of the zinc-coordinating histidine in a rotameric state compatible with zinc binding (65). In TTP and TIS11d, the conserved aromatic moiety is in the center of the short α-helix located between the first and second cysteine residues and is properly posed to stack against the side chain of the histidine residue.

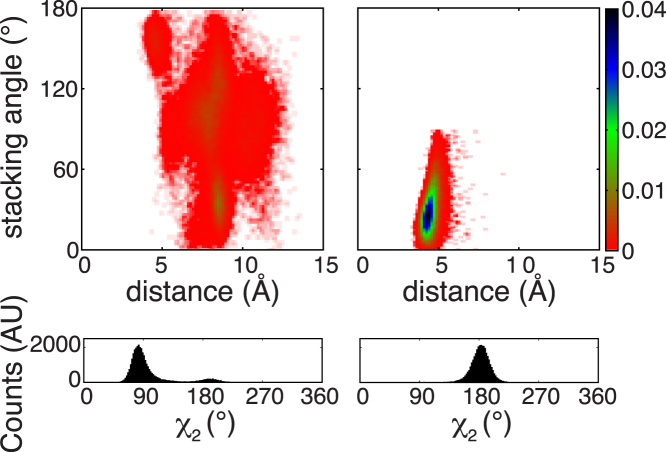

In light of this observation, we determined whether such aromatic stacking interactions were present in the two zinc fingers of MEX-5 during our MD simulations. We observed that this is the case in the C-terminal zinc finger, where His341 stacks against Phe323. As a result, the side chain of the histidine is constrained in the rotameric state characterized by the dihedral angle χ2 centered at 180° (see Fig. 4). The formation of this stacking interaction is supported experimentally by the presence of a strong NOE between Phe323 and His341 (see Fig. S8). In this conformation, the zinc-coordinating residues properly and stably coordinate the zinc ion with a tetrahedral geometry. In contrast, our simulations showed that in the N-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5, the stacking between His279, the equivalent residue to Phe323 in ZF2, and His296 was not maintained along the trajectories. As a result, His296 samples multiple rotameric states (Fig. 4). Therefore, the geometry of the zinc-coordinating residues deviates from the ideal tetrahedral geometry, and in two trajectories, we observed the displacement of at least one cysteine from the zinc-binding site.

Figure 4.

The zinc-coordinating His residue populates many rotameric states in ZF1 but only one state in ZF2. Top: probability density distributions of the stacking angle and distance between the stacked aromatic rings are shown for His279 and His296 in MEX-5 ZF1 (left) and for Phe323 and His341 in MEX-5 ZF2 (right). The color bars show the values of the probability density calculated for the stacking angle and distance as the number of counts normalized by the total number of observations and by the area of each bin. Configurations and distributions were extracted from three 50-ns MD trajectories. Bottom: probability distributions of the dihedral angle χ2 are shown for the zinc-coordinating histidines H296 (left) and H341 (right). To see this figure in color, go online.

Conformational transition of the Cys276-Cys286 region is associated with the loss of the His279-His296 stacking interaction

To further characterize the structural differences between the two zinc fingers of MEX-5, we used MD to analyze the factors affecting the conformation of the aromatic residues whose stacking against the zinc-coordinating histidine results in stabilization of Zn2+ binding. In ZF1 and ZF2, these aromatic residues are His279 and Phe323, respectively. Upon analysis of the of the zinc-coordinating histidine in the initial structure of MEX-5 built from homology modeling using the structure of TIS11d, we observed a clear difference between the N- and C-terminal zinc fingers. In each trajectory, the side chain of the zinc-coordinating histidine in the N-terminal zinc finger, His296, is in different rotameric states, whereas His341, in the C-terminal zinc finger, is constrained to a single rotameric state by the stacking interaction with Phe323. In two of the three trajectories, however, after an initial structural equilibration (∼5–10 ns), the side chains of His279 and His296 form a π-π stacking interaction, and as a result, the imidazole moiety of His296 populates a rotameric state corresponding to χ2 = 180°, compatible with Zn2+ binding (Fig. 4). In the third trajectory, the zinc coordination in ZF1 is perturbed during the initial equilibration, with a resulting bipyramidal geometry due to the presence of two water molecules in the zinc-binding pocket.

The stacking interaction observed for ZF1 in two of the three trajectories, however, is only short lived: 7 and 5 ns in each trajectory, respectively. For the period in which the stacking interaction between His279 and His296 is present, zinc is coordinated in ZF1 with the expected tetrahedral geometry. Subsequently, the region between the first and the second zinc-coordinating cysteine, Cys276 and Cys286, undergoes a conformational transition (Fig. S9) that results in an altered geometry of the zinc coordination and eventually in the displacement of Cys286 from the zinc-binding pocket. We observed that, along the MD trajectories, the region between Met278 and Cys286 samples two states, corresponding to conformations with and without the stacking between His279 and His296, respectively. The conformation that allows for proper stacking is characterized by the same backbone dihedral angles, ϕ and ψ, observed in the corresponding residues in ZF2 and contains a 310-helix turn between Cys276 and Ala280 (see Fig. S9).

Comparing the structural features of ZF1 in the stacking and nonstacking conformations, we observed that different hydrogen bonds occur within the region between the first two cysteine residues (see Fig. S10, A and B). The presence of hydrogen bonds between Cys276 and Met278 and His279 and Ala280 (Met278 HN-Cys276 S, His279 HN-Cys276 O and Ala280 HN-Cys276 O) characterizes the conformations in which stacking between His279 and His296 is observed. The equivalent hydrogen bonds are present in ZF2 (Asn322 HN-Cys320 S, Phe323 HN-Cys 320 O, and Ala324 HN-Cys320 O), in which stacking between Phe323 and His341 is stable. In ZF2, however, hydrogen bonds between Lys321 and Ala324 or Arg325 are more stable than the equivalent hydrogen bonds in ZF1 (between Met277 and His279 or Ala280), in which they are present only with low probability. Two additional hydrogen bonds, centered on Asn322, stabilize the structure of ZF2 but are absent in ZF1: Gly329 HN-Asn322 O and Asn322 Hδ2-Cys331 S or Asn322 Hδ2-Phe330 O. The presence of all these stable hydrogen bonds is in agreement with our NMR data, in which we observed several NOEs between the residues in the 321–324 region and between Asn322 and the residues in the 328–332 region (highlighted with circles in Fig. S8). Therefore, more hydrogen bonds stabilize the 310-helix turn between Cys320 to Ala324 in ZF2 than the equivalent 310-helix turn between Cys276 and Ala280 in ZF1. For this reason, the 310-helix turn of ZF1 is sampled with low probability. Finally, we observed that a hydrogen bond between His279 Nδ1 and Gly282 O stabilizes the conformation of His279 in a rotameric state compatible with stacking against His296; formation of this hydrogen bond correlates with the presence of aromatic stacking between His279 and His296 (see Fig. S11). All the hydrogen bonds described above are lost when His279 is not stacked against His296.

Rational design of a mutant of MEX-5 with a folded N-terminal zinc finger

Our MD simulations of MEX-5 revealed that in ZF1, the stacking between the side chains of His279 and His296 is not stable and results in destabilization of zinc coordination in ZF1. Analysis of the MD trajectories highlighted the critical role of many hydrogen bonds between the first and second cysteine residues in determining the structure of the zinc finger. In addition, comparison of MEX-5 to other CCCH-type zinc finger proteins shows that the amino acid sequence between the first and second cysteine residues displays the highest degree of diversity. In particular, the spacing between the first two coordinating cysteines is nine and ten residues for ZF1 and ZF2 of MEX-5, respectively, and eight residues for the other proteins of the family (see Fig. 1). From these observations, we hypothesized that the region between the first and second cysteine residues is important in determining the stability of the zinc finger. To test this hypothesis, we generated a series of mutants of the TZF domain of MEX-5, in which, in turn, the sequence of the Cys276-Cys286 fragment of ZF1 is replaced with the corresponding sequence of ZF2 (see Table 2).

The first mutation (Mutant A) in Table 2 was designed to test the hypothesis that the stacking interaction was less stable in ZF1 than in ZF2 because it is formed with a histidine residue rather than with a phenylalanine. The second mutation (Mutant B) was designed to determine whether the reduced flexibility of a proline residue relative to that of a phenylalanine can account for the difference in structure observed between ZF1 and ZF2. The third and fourth mutations (Mutants C and D) were designed to evaluate whether an extra amino acid is sufficient to stabilize the structure of ZF1. The fifth and sixth mutant variants (Mutants E and F) were designed to evaluate the effect of the increased flexibility of the glycine-rich loop present in ZF2 but not in ZF1. The seventh and eighth variants (Mutants G and H) were designed to test the effect of the two hydrogen bonds formed by Asn in stabilizing the structure of the finger. Lastly, the entire region between Cys296-Cys286 was replaced with the homologous sequence from ZF2 (Cys320-Cys331); this construct will be referred as MEX-5CX10C.

We investigated the effects of the introduced mutations on the structure of ZF1 by monitoring the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the variants of MEX-5. The construct MEX-5CX10C was the only one that displayed a significant difference in the spectrum compared to the wild-type domain (see Figs. 5 A and S12); we observed 73 crosspeaks in the spectrum (one peak corresponding to each amino acid in this construct, except for prolines), with those corresponding to the C-terminal zinc finger having the same chemical shifts as in the wild-type. All the other mutants described in Table 2 produced 1H-15N HSQC spectra with a similar number of crosspeaks as in the wild-type domain, indicating that in these MEX-5 variants, ZF1 does not stably coordinate zinc. These results indicate that in the variant MEX-5CX10C, both the zinc fingers are folded and coordinate zinc ions in the RNA-free form, whereas in the other variants, ZF1 is unstructured. These results support our MD results that the stability of the zinc finger is achieved through the concerted formation of several hydrogen bonds involving different residues located between the first and second cystine residues.

Figure 5.

The TZF domain of MEX-5CX10C is folded in the RNA-free state. (A) The 15N-1H HSQC spectrum of MEX-5CX10C TZF domain shows 78 crosspeaks, indicating that the domain is folded. (B) Shown is the Zn2+ titration of the TZF domain of MEX-5 and of the variant MEX-5CX10C, followed by NMR spectroscopy. The average crosspeak intensities from the 15N-1H HSQC spectra are shown as a function of zinc equivalents added to the protein, errors are estimated from the standard deviation. A linear regression is applied to the first part of each curve, and the resulting slope is shown in the plot. To see this figure in color, go online.

To confirm that both zinc fingers of the MEX-5CX10C variant are folded, we measured the zinc-binding stoichiometry of the TZF domain of MEX-5CX10C. We collected a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra at increasing concentration of zinc ions, and we observed that, as expected, the end point of the titration curve occurred at two equivalents of zinc (see Fig. 5 B).

Characterization of the RNA-binding activity of the mutant MEX-5

As discussed above, the mutations introduced in the construct MEX-5CX10C (see Table 2) had the effect of stabilizing the structure of ZF1, which stably coordinates zinc in the absence of RNA. To determine the effect of this structural change on the RNA-binding activity of MEX-5, we measured the apparent dissociation constant of the wild-type and the mutant variant TZF domain with four different RNA oligonucleotides. The choice of the RNA target sequences was guided by the rationale that, as observed for TTP and TIS11d (52,54), each zinc finger binds to a four-nucleotide-long, U-rich motif, with higher affinity for the UAUU sequence. Thus, we measured the binding affinity of the mutated TZF domain to oligonucleotides containing the UAUU and UUUU elements in different arrangements (see Fig. S13). The results obtained for this mutant variant were compared with those of the wild-type and show that the mutated TZF domain of MEX-5, as observed for the wild-type, binds with highest affinity to the UUUUAUUUAUUUU oligonucleotide. For all the tested sequences, we observed no substantial differences in binding affinity between mutated and wild-type domains (<2-fold). Because binding is coupled to ZF1 folding in wild-type MEX-5 (MEX-5WT), the free energy change measured upon binding will have contributions from both the folding of ZF1 and the association with RNA. This is not true for MEX-5CX10C, where both zinc fingers are folded in the free state. For this reason, we were surprised to observe that the two MEX-5 variants bind RNA with similar affinities. In MEX-5WT, folding of ZF1 is likely to make a favorable enthalpic contribution and an unfavorable entropic contribution to the free energy change measured upon RNA binding; this entropy-enthalpy compensation may explain the similar RNA-binding affinity measured for the two MEX-5 variants. Differences in amino acid composition between the two proteins (see Table 2) may also affect the thermodynamics of RNA binding. For this reason, a direct comparison of the binding free energy changes of MEX-5WT and MEX-5CX10C is difficult. For example, the hydrophobic amino acid content of MEX-5WT is higher than that of MEX-5CX10C: of the 9 aa that differ between the two variants, 5 aa are hydrophobic in MEX-5WT, whereas only 3 aa are hydrophobic in MEX-5CX10C. As a result, the binding entropies of the two MEX-5 variants will have different desolvation contributions: relative to MEX-5CX10C, MEX-5WT will have a lower entropic penalty upon binding because of the desolvation of a higher number of hydrophobic residues that may offset the entropic cost of folding ZF1 (68). MEX-5CX10C also contains an additional charged residue that can contribute to a different interaction energy with RNA relative to the wild-type protein. Moreover, the stacking interaction that stabilizes the conformation of the zinc-coordinating histidine is different between the two proteins (His279-His296 in MEX-5WT and Phe279-His296 in MEX-5CX10C) and can also contribute to the relative free energy of binding.

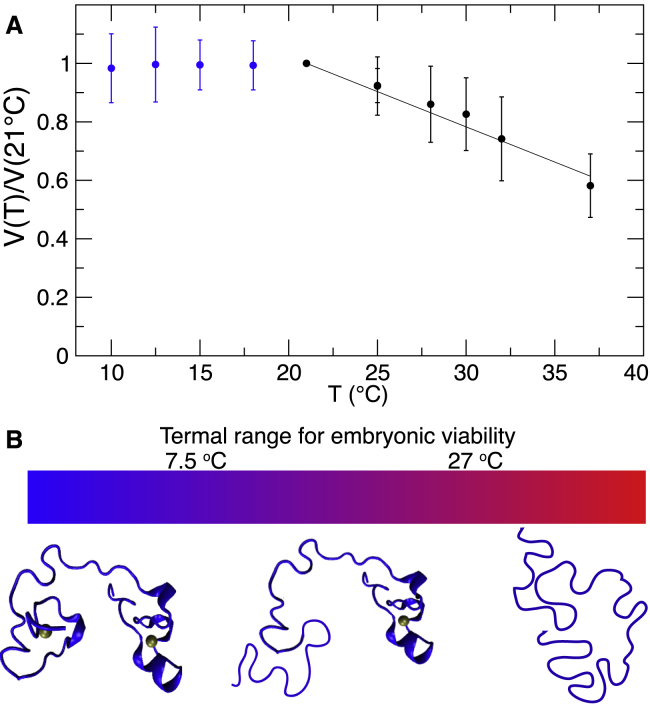

The structure of the MEX-5 TZF domain is dependent on the temperature

To study the effect of the temperature of the structure of MEX-5, we collected a series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra at different temperatures varying between 281 and 310 K. We observed that the volume of the crosspeaks corresponding to the linker and C-terminal zinc finger was constant in the spectra collected at temperatures between 281 and 294 K but progressively decreased as the temperature was increased above 294 K (Fig. 6 A), indicating that the C-terminal zinc finger begins to unfold at T > 294 K. At temperatures lower than 288 K, we observed eight crosspeaks corresponding to residues in the N-terminal zinc finger with low intensity. These eight crosspeaks overlapped with peaks present in the HSQC spectrum of the MEX-5 variant, MEX-5CX10C, in which both zinc fingers are folded. The fact that the chemical shifts for these crosspeaks are the same as those measured for the MEX-5 variant with a folded ZF1 indicates that at T < 288, the N-terminal zinc finger begins to fold. These crosspeaks were barely above the noise at 288 K, but their intensity increased with decreasing temperatures, whereas they were beyond detection at temperatures higher than 288 K. Assuming that the N-terminal zinc finger is 100% folded in MEX-5CX10C and using the volume of the crosspeaks in the MEX-5CX10C spectrum as a reference, we estimated that these residues from the N-terminal zinc finger populate the folded state to ∼30 ± 10% at 281 K. These results show that in the range of temperatures in which C. elegans is fertile, between 282 and 298 K (24), the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5 is stably folded, whereas the N-terminal zinc finger is only folded with low probability. Outside of this temperature range, the structure of MEX-5 changes: at temperatures lower than 282 K, the population of MEX-5 with both zinc fingers folded increases, whereas at temperatures higher than 298 K, an increasing population of MEX-5 has both zinc fingers unfolded (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

Temperature effect on the structure of the TZF domains of MEX-5. (A) The ratio of the crosspeak volume at a given temperature over the volume measured at T = 21°C is averaged for all the peaks of the C-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5, errors are estimated from the standard deviation. (B) A schematic representation of how the structure changes as a function of temperature is shown.

To evaluate whether RNA binding stabilized the structure of MEX-5, we measured the RNA-binding affinity of MEX-5 for UUUUAUUUAUUUU at different temperatures varying between 299 and 318 K, a range of temperatures in which, in the absence of RNA, ZF1 is unfolded, and the amount of unfolded ZF2 increases progressively (Fig. 6 A). The instrument used dictated the range of temperatures that we were able to sample in these experiments. A van’t Hoff plot of ln Ka,app as a function of 1/T shows a small deviation from a linear dependence. The data were fitted to a straight line as a function of ΔH, ΔS (Eq. 2), and to a three-parameter curve including ΔH, ΔS, and ΔCp (Eq. 3), as shown in Fig. S14. The two models were compared using F statistics: the three-parameter model, which included ΔCp, was the most appropriate for the data. The best fit of the binding constants, Ka,app, was obtained with the following parameters: ΔH = −13 ± 2 kcal mol−1, ΔS = −0.010 ± 0.006 kcal mol−1 K−1, and ΔCp = −0.7 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1 K−1 at a reference temperature of 298.15 K. These data show that for MEX-5, RNA binding is enthalpically driven but entropically disfavored. The negative ΔCp of binding is likely to result from the removal of hydrophobic surfaces from water that occurs upon folding of ZF1 of MEX-5 and upon the association of MEX-5 with the RNA bases (69, 70, 71, 72). The good fit of the data indicates that MEX-5 is able to bind RNA even at the highest temperature used in the experiment, when, in the absence of RNA, approximately half of the protein is unstructured. These results indicate that RNA binding stabilizes the folded state of MEX-5.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized the structure of the TZF domain of MEX-5 (residues 268–346). We demonstrated that, in the temperature range in which C. elegans is fertile, the N-terminal zinc finger of MEX-5 is mostly unstructured and unable to coordinate a zinc ion in the RNA-free form but undergoes a disorder-to-order transition upon RNA binding. This coupled folding-binding process can occur through one of the following mechanisms or through a combination of the two: 1) binding of ZF2 to RNA can induce folding of ZF1, and thus, folding is induced by binding; and 2) alternatively, RNA can capture a conformation of MEX-5 in which both zinc fingers are folded; in this case, RNA binding would follow a conformational selection mechanism. RNA binding stabilizes the structure of MEX-5, which remains folded at a higher temperature than in the free state. We also showed that ZF2 of MEX-5 can fold independently: the peptide fragment containing the C-terminal zinc finger assumes the same fold of the ZF in the full-length domain. By solving the solution structure of ZF2, we observed that although maintaining common structural features, the backbone conformation of the domain presents some differences from the two other structures so far solved for the members of the protein family, TIS11d (54) and POS-1 (A.E. and F.M., unpublished data). For example, we observed that, like TTP, TIS11d, and POS-1, the stacking of the zinc-coordinating histidine against an aromatic residue is necessary to maintain the histidine side chain in a rotameric state compatible with Zn2+ binding. On the other hand, the zinc finger of MEX-5 contains a shorter helix (four residues long) than what is observed in both TIS11d and POS-1, where the helix is six residues long and forms two turns (Fig. 3 C). The shorter helix observed in MEX-5 followed by the glycine-rich flexible loop (Fig. 3) may be important in defining the low RNA-binding specificity observed for MEX-5 relative to TTP and TIS11d. A certain consequence of the shorter helix is that a complex network of hydrogen bonds is required in MEX-5 to maintain the aromatic side chain (His279 and Phe323 in ZF1 and ZF2, respectively) in a conformation suitable to stack against the side chain of the zinc-coordinating histidine. This mechanism is different from what we observed in TTP and TIS11d, in which only one hydrogen bond was necessary to stabilize the conformation of the Phe side chain in a position where it could stack against the zinc-coordinating histidine (65). We identified key interactions within the ZFs of MEX-5 that stabilize zinc binding, and we validated these findings by designing a variant of the MEX-5 TZF domain that has both zinc fingers structured in the RNA-free state. This variant MEX-5 TZF domain still binds RNA with the same specificity as the wild-type domain.

Our findings provide new insights on the regulation of MEX-5 activity in C. elegans. It has been shown that the extent of structure in the free state of intrinsically disordered proteins can affect their biological activity (47,73). In particular, a disorder-to-order transition upon RNA binding, similar to the one described here for MEX-5, has been observed for another protein in the CCCH-type TZF family, the human TTP, but not in the homolog TIS11d. Previous studies have determined the effect of having a fully folded, RNA-binding domain on the cellular activity of TTP using a luciferase reporter assay, in which luciferase was placed under the control of the TNF-α 3′-UTR (47). Decreased reporter activity was observed when the partially unstructured RNA-binding domain of TTP was replaced with the fully structured domain of TIS11d, indicating that the increased structure is associated with higher RNA-degradation activity (47). This result showed that folding of the RNA-binding domain is tightly coupled with TTP and TIS11d activities in the cell. We observed that the TZF domain of MEX-5 has evolved to be partially structured only in the narrow range of temperatures in which the animal is able to reproduce, which corresponds to the range of temperatures in which MEX-5 needs to function because it plays a critical role during embryogenesis. In a similar manner to TTP, we hypothesize that having a partially structured TZF domain gives an additional degree of regulation to MEX-5 apart from phosphorylation that could confer functional advantages.

During the early stages of embryogenesis, MEX-5 contributes to the polarization of the body axes in the zygote distributing in the cytoplasm along an anterior-rich gradient and, in turn, establishing posterior segregation of other fate determinants, such as POS-1 and PIE-1. The MEX-5 distribution pattern in the cytoplasm depends on its RNA-binding activity and its phosphorylation state. These asymmetric protein distribution patterns in the one-cell embryo are retained upon cell divisions and result in the separation of the somatic lineage (anterior) and the germline (posterior). The degree of disorder of the TZF domain of MEX-5 may modulate its distribution in the zygote in several ways. For example, to bind RNA, MEX-5 requires spatially and timely availability of zinc ions in the cytoplasm to allow folding of the N-terminal zinc finger. In addition, both zinc fingers need to be folded for RNA binding, and folding involves a conformational entropic cost that has to be compensated by a favorable enthalpic contribution to the binding energy. In MEX-5, the population of folded state of the TZF domain is highly dependent on the temperature; consequently, the thermodynamics of RNA binding is also dependent on the temperature. Because the RNA-binding activity is essential for the function of MEX-5 in embryogenesis, we expect MEX-5 function to be also modulated by the temperature of the environment.

Author Contributions

D.T., A.E., S.P.R., and F.M. designed the experiments. D.T. performed the simulations and analyzed the corresponding results. D.T., A.E., and H.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the results. D.T. wrote the article with F.M.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Troy W. Whitfield for helpful discussions and C. Robert Matthews for sharing equipment.

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01 GM117008 (to F.M. and S.P.R.) and 2 R25 HL092610-11 (to H.S.), respectively.

Editor: Daniel Raleigh.

Footnotes

Davide Tavella’s present address is AbbVie Bioresearch Center, Worcester, Massachusetts 01605.

Hila Schaal’s present address is Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.02.032.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Hwang S.Y., Rose L.S. Control of asymmetric cell division in early C. elegans embryogenesis: teaming-up translational repression and protein degradation. BMB Rep. 2010;43:69–78. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2010.43.2.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumano G. Polarizing animal cells via mRNA localization in oogenesis and early development. Dev. Growth Differ. 2012;54:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein B., Macara I.G. The PAR proteins: fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Dev. Cell. 2007;13:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St Johnston D., Ahringer J. Cell polarity in eggs and epithelia: parallels and diversity. Cell. 2010;141:757–774. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffin E.E. Cytoplasmic localization and asymmetric division in the early embryo of Caenorhabditis elegans. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2015;4:267–282. doi: 10.1002/wdev.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose L.S., Kemphues K.J. Early patterning of the C. elegans embryo. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1998;32:521–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schubert C.M., Lin R., Priess J.R. MEX-5 and MEX-6 function to establish soma/germline asymmetry in early C. elegans embryos. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:671–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tenlen J.R., Molk J.N., Priess J.R. MEX-5 asymmetry in one-cell C. elegans embryos requires PAR-4- and PAR-1-dependent phosphorylation. Development. 2008;135:3665–3675. doi: 10.1242/dev.027060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown G.C., Kholodenko B.N. Spatial gradients of cellular phospho-proteins. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:452–454. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipkow K., Odde D.J. Model for protein concentration gradients in the cytoplasm. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2008;1:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s12195-008-0008-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin E.E., Odde D.J., Seydoux G. Regulation of the MEX-5 gradient by a spatially segregated kinase/phosphatase cycle. Cell. 2011;146:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budirahardja Y., Gönczy P. PLK-1 asymmetry contributes to asynchronous cell division of C. elegans embryos. Development. 2008;135:1303–1313. doi: 10.1242/dev.019075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mello C.C., Schubert C., Priess J.R. The PIE-1 protein and germline specification in C. elegans embryos. Nature. 1996;382:710–712. doi: 10.1038/382710a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivers D.M., Moreno S., Ahringer J. PAR proteins direct asymmetry of the cell cycle regulators Polo-like kinase and Cdc25. J. Cell Biol. 2008;180:877–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pagano J.M., Farley B.M., Ryder S.P. Molecular basis of RNA recognition by the embryonic polarity determinant MEX-5. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:8883–8894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallo C.M., Munro E., Seydoux G. Processing bodies and germ granules are distinct RNA granules that interact in C. elegans embryos. Dev. Biol. 2008;323:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han B., Antkowiak K.R., Griffin E.E. Polo-like kinase couples cytoplasmic protein gradients in the C. elegans zygote. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:60–69.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trcek T., Lehmann R. All about the RNA after all. eLife. 2017;6:e24106. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith J., Calidas D., Seydoux G. Spatial patterning of P granules by RNA-induced phase separation of the intrinsically-disordered protein MEG-3. eLife. 2016;5:e21337. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saha S., Weber C.A., Hyman A.A. Polar positioning of phase-separated liquid compartments in cells regulated by an mRNA competition mechanism. Cell. 2016;166:1572–1584.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varnum B.C., Lim R.W., Herschman H.R. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate induce a distinct, restricted subset of primary-response TIS genes in both proliferating and terminally differentiated myeloid cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:3580–3583. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuBois R.N., McLane M.W., Nathans D. A growth factor-inducible nuclear protein with a novel cysteine/histidine repetitive sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:19185–19191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai W.S., Stumpo D.J., Blackshear P.J. Rapid insulin-stimulated accumulation of an mRNA encoding a proline-rich protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:16556–16563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neves A., Busso C., Gönczy P. Cellular hallmarks reveal restricted aerobic metabolism at thermal limits. eLife. 2015;4:e04810. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goddard T.D., Kneller D.G. University of California; San Francisco, CA: 2007. SPARKY 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loria J.P., Rance M., Palmer A.G. A relaxation-compensated Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence for characterizing chemical exchange by NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2331–2332. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korzhnev D.M., Kloiber K., Kay L.E. Multiple-quantum relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy probing millisecond time-scale dynamics in proteins: theory and application. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:7320–7329. doi: 10.1021/ja049968b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Güntert P., Buchner L. Combined automated NOE assignment and structure calculation with CYANA. J. Biomol. NMR. 2015;62:453–471. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9924-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen Y., Delaglio F., Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brünger A.T., Adams P.D., Warren G.L. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunger A.T. Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhattacharya A., Tejero R., Montelione G.T. Evaluating protein structures determined by structural genomics consortia. Proteins. 2007;66:778–795. doi: 10.1002/prot.21165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y.J., Rosato A., Montelione G.T. RPF: a quality assessment tool for protein NMR structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W542–W546. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bordoli L., Kiefer F., Schwede T. Protein structure homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL workspace. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1–13. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arnold K., Bordoli L., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwede T., Kopp J., Peitsch M.C. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakharov D.V., Lim C. Zn protein simulations including charge transfer and local polarization effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4921–4929. doi: 10.1021/ja0429115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryckaert J.P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1997;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darden T., York D.M., Pedersen L.G. Particle mesh Ewald: an N log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;96:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Frishman D., Argos P. Knowledge-based protein secondary structure assignment. Proteins. 1995;23:566–579. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stone J. An efficient library for parallel ray tracing and animation. Master’s thesis (University of Missouri-Rolla) 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deveau L.M., Massi F. Three residues make an evolutionary switch for folding and RNA-destabilizing activity in the TTP family of proteins. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:435–443. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abramoff M., Magalhaes P., Ram S. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophoton. Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pagano J.M., Clingman C.C., Ryder S.P. Quantitative approaches to monitor protein-nucleic acid interactions using fluorescent probes. RNA. 2011;17:14–20. doi: 10.1261/rna.2428111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dyson H.J., Wright P.E. Unfolded proteins and protein folding studied by NMR. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3607–3622. doi: 10.1021/cr030403s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blackshear P.J., Lai W.S., Zhou P. Characteristics of the interaction of a synthetic human tristetraprolin tandem zinc finger peptide with AU-rich element-containing RNA substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19947–19955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palmer A.G., III NMR characterization of the dynamics of biomacromolecules. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3623–3640. doi: 10.1021/cr030413t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hudson B.P., Martinez-Yamout M.A., Wright P.E. Recognition of the mRNA AU-rich element by the zinc finger domain of TIS11d. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:257–264. doi: 10.1038/nsmb738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Romero P., Obradovic Z., Dunker A. Proceedings of International Conference on Neural Networks (ICNN’97). (IEEE) 1997. Identifying disordered regions in proteins from amino acid sequence; pp. 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garner E., Cannon P., Dunker A.K. Predicting disordered regions from amino acid sequence: common themes despite differing structural characterization. Genome Inform. Ser. Workshop Genome Inform. 1998;9:201–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garner E., Romero P., Obradovic Z. Predicting binding regions within disordered proteins. Genome Inform. Ser. Workshop Genome Inform. 1999;10:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng K., Vucetic S., Obradovic Z. Optimizing long intrinsic disorder predictors with protein evolutionary information. J. Bioinform. Comput. Biol. 2005;3:35–60. doi: 10.1142/s0219720005000886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng K., Radivojac P., Obradovic Z. Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunker A.K., Lawson J.D., Obradovic Z. Intrinsically disordered protein. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2001;19:26–59. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(00)00138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson D.E., Xue B., Uversky V.N. High-throughput characterization of intrinsic disorder in proteins from the Protein Structure Initiative. J. Struct. Biol. 2012;180:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xue B., Williams R.W., Uversky V.N. Archaic chaos: intrinsically disordered proteins in Archaea. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4(Suppl 1):S1–S21. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farley B.M., Pagano J.M., Ryder S.P. RNA target specificity of the embryonic cell fate determinant POS-1. RNA. 2008;14:2685–2697. doi: 10.1261/rna.1256708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaymak E., Ryder S.P. RNA recognition by the Caenorhabditis elegans oocyte maturation determinant OMA-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:30463–30472. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.496547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]