Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are membrane-bound proteins that depend on their lipid environment to carry out their physiological function. Combined efforts from many theoretical and experimental studies on the lipid-protein interaction profile of several GPCRs hint at an intricate relationship of these receptors with their surrounding membrane environment, with several lipids emerging as particularly important. Using coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations, we explore the lipid-protein interaction profiles of 28 different GPCRs, spanning different levels of classification and conformational states and totaling to 1 ms of simulation time. We find a close relationship with lipids for all GPCRs simulated, in particular, cholesterol and phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) lipids, but the number, location, and estimated strength of these interactions is dependent on the specific GPCR as well as its conformational state. Although both cholesterol and PIP lipids bind specifically to GPCRs, they utilize distinct mechanisms. Interactions with PIP lipids are mediated by charge-charge interactions with intracellular loop residues and stabilized by one or both of the transmembrane helices linked by the loop. Interactions with cholesterol, on the other hand, are mediated by a hydrophobic environment, usually made up of residues from more than one helix, capable of accommodating its ring structure and stabilized by interactions with aromatic and charged/polar residues. Cholesterol binding to GPCRs occurs in a small number of sites, some of which (like the binding site on the extracellular side of transmembrane 6/7) are shared among many class A GPCRs. Combined with a thorough investigation of the local membrane structure, our results provide a detailed picture of GPCR-lipid interactions. Additionally, we provide an accompanying website to interactively explore the lipid-protein interaction profile of all GPCRs simulated to facilitate analysis and comparison of our data.

Significance

Membrane proteins carry out their function and activity in an environment composed of many different lipid types. Despite this heterogeneity, membrane proteins have been shown to associate preferably with some lipids, most notably cholesterol, over others. We selected 28 different G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) from different families and simulated them using the same simulation setup and protocol. Analysis of the simulation data reveals specific interactions with lipids for all GPCRs as well as overall lipid interaction profiles that are unique to each GPCR structure and conformational state. Cholesterol and phosphatidylinositol phosphate lipids are the most prominent lipid types forming specific interactions with GPCRs, and we find that they do so by employing different mechanisms.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of membrane protein receptors, both in size and in the diversity of their physiological functions (1). Their structure consists of a structurally conserved seven transmembrane (TM) helical core whose sequence spans the full length of the membrane bilayer and ends with an eighth helix that stretches along the intracellular side of the membrane. The individual helices of the helical core are connected via three intracellular and three extracellular loops. GPCRs are essential drug targets, accounting for an estimated 1/3 of prescribed drugs (2,3).

One aspect that has attracted substantial attention, especially in the last decade, has been the ability of the membrane environment to guide or otherwise exert influence on GPCR activity and function. Two modes of modulation have been proposed in the literature: 1) direct and specific lipid-protein interactions and 2) altering of membrane physical properties (e.g., thickness, curvature, etc.) (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, either alone or in conjunction with experiments, have repeatedly shown that lipids can and often do affect the activity of membrane-embedded proteins. Recent in-depth reviews on the lipid-protein interaction landscape as it emerges from hundreds of MD simulation studies highlight the prevalence of such interactions with various membrane proteins, with a particular emphasis on GPCRs, their possible biological relevancy, and the importance of computational methods as essential tools in deciphering these interactions (11, 12, 13, 14, 15).

Among the most studied GPCRs in the literature are β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), adenosine A2A receptor (A2AR), and rhodopsin (RhodR, the complete list of abbreviations used in this study is given in Table S1; (11,16)). Microsecond-long MD simulations of β2AR (17), for example, reveal several interaction sites for cholesterol distributed unequally between the extracellular (ec) and intracellular (ic) sides of the receptor and differing in their relative strength of binding to the receptor. These interaction sites were later supported by longer and a more diverse set of simulations (18). Similarly, for A2AR, combined all-atom and coarse-grained MD simulations from independent studies show A2AR to be interacting with cholesterol at several interaction sites (19). Two sites, in particular, are noted for their cholesterol binding affinity: TM5/6 (ic) and TM6 (ec) (20). Rhodopsin, as well, has been shown to interact with cholesterol and docosahexaenoic acid lipids in a ligand-like manner (21). One such potential interaction with cholesterol, for instance, is located between helices TM7/1 of the receptor (22). Bulk lipid properties, in addition to specific lipid-protein interactions, have also been proposed as determining factors in rhodopsin activity (23). Specific lipid-GPCR interactions are believed to serve biologically important roles, with some interactions capable of acting as allosteric modulators of receptor activity, confer stability to the receptor, and may increase the coupling selectivity to effector proteins (24,25). The effect of membrane bulk lipid properties, rather than individual membrane components, is less well documented, but its importance has been highlighted for serotonin (5HT1AR) (26) and rhodopsin (21). MD simulations of other GPCRs, including serotonin (27), opioid receptors (28), and class F smoothened (SMO) (29), consistently show specific interactions of GPCRs with cholesterol. Moreover, simulations of β2AR and A2AR show cholesterol to not only have a different interaction profile depending on the state of the receptor (19) but also affect the conformational transition from active to inactive state of the receptor by restricting its conformational landscape (18). Experimental data, although scarcer, generally agree with the conclusions reached by MD simulations (24,25,30).

Despite the clear progress made, several aspects of GPCR-lipid interactions remain hidden. The majority of studies focus only on a few GPCRs, and MD simulations protocols used to study lipid-protein interactions differ in design and execution, making both the comparison of results as well as the extrapolation of data to other GPCRs difficult (a noteworthy exception is the work of Yen et al. in which they did analyze the phosphatidylinositol phosphate (PIP) interaction profile of nine class A GPCRs) (25). Additionally, in the last few years, we have learned that to obtain statistically accurate lipid distributions around proteins, microsecond-long simulations are required (17,20,31). This makes interpreting older simulation articles and resolving conflicting findings particularly challenging.

Recently, we developed a protocol to study lipid-protein interactions using the Martini model (32) by employing a highly realistic membrane model and long timescale simulations (31). We successfully applied the protocol to 10 different proteins, and we showed that the lipid interaction profile of proteins is a defining feature of their structure, expressed as a combination of specific and long-lasting interactions formed with individual lipids and the resultant membrane thickness and curvature caused by the disordering of the local membrane structure.

In this study, we have used our simulation protocol to study GPCR-lipid interactions. We have simulated 23 different GPCR structures, five of which we simulated in both the active and inactive state, totaling to 28 different structures (Table S1). Each GPCR has been simulated in a system containing four copies of itself for 30 μs. Altogether, after accounting for control simulations, we present data on GPCR-lipid interactions from a total of 1 ms simulation time. Our usage of a consistent protocol and identical simulation parameters coupled with the large number of GPCRs simulated allows us to study the lipid interaction profile of each GPCR separately as well as present our findings in a GPCR family-wide context. We show that GPCRs, through lipid-protein interactions, create a local membrane environment that is unique for each receptor.

Methods

System setup

The initial protein coordinates for all GPCRs were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. The corresponding Protein Data Bank (PDB) IDs and references are shown in Table S1. For each GPCR, nonprotein molecules and atoms were removed. Attached protein fragments were also excluded from the simulations, leaving only the helical core (including helix 8) and extra- and intracellular loops. The resulting structures were converted to a coarse-grained (CG) model using the Martinize protocol as outlined on the Martini website (http://www.cgmartini.nl/) and inserted into a bilayer using the insane tool (33). The secondary and tertiary structure of GPCRs were maintained using an elastic network. We have simulated 23 different GPCR structures belonging to class A, and five non-class A GPCRs, totaling 28 different GPCR structures simulated. 5 GPCRs (receptors adenosine 2A, β2, rhodopsin, M2 muscarinic acetylcholine, and μ-opioid) are simulated in both the active and inactive conformational state. Each system was simulated for 30 μs, and unless otherwise specified, analysis was performed on the last 5 μs of each trajectory. The total simulation time for this project, including the control simulations, is around 1 ms.

To test if our simulation protocol has any effect on our results, we performed three control simulations for β2AR (Fig. S2):

-

1)

Including ICL2 to test if its exclusion from our simulations has any effect,

-

2)

Including the palmitoylated Cys-341, and

-

3)

Pre-equilibrating the system for 100 ns using all-atom simulations. Manna et al. (34) highlighted the importance of a proper equilibration protocol for β2AR when carrying out all-atom MD simulations, so we wanted to ensure that our direct conversion of protein coordinates to a coarse-grained representation did not affect our results.

The overall system setup follows our recently published protocol, in which four copies of each protein are embedded equidistantly in a simulation box of ∼40 × 40 nm in the x and y plane. We find this surface area to be adequate in allowing both the insertion of multiple (here, four) protein copies as well as maintaining accurate ratios between lipids in the system, in particular those found at low concentrations. In comparison with simulating multiple copies of smaller setups containing one protein each, our setup enables us to have a much better representation of all lipid types in the system and allow for lipids to sample a larger area and thus completely escape the influence of embedded proteins. The lipid composition of our systems corresponds to the plasma membrane model developed by Ingólfsson et al. (35) and later applied to several protein systems (31). The exact lipid composition for each system simulated is described in Table S6, but in general, the outer leaflet contains ganglioside (GM) lipids, and the inner leaflet contains phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidic acid (PA), phosphatidylinositol (PI), and PI-phosphate, -bisphosphate, and -trisphosphate (PIP lipids). Both membrane leaflets contain cholesterol (CHOL), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and sphingomyelin (SM) lipids. Small amounts of lysophosphatidylcholine, diacylglycerol, and ceramide were also included. For GM lipids, we used the new parameters (36). The membrane system with embedded protein was generated using the insane protocol, resulting in a composition with ∼5200 residues (including proteins) and 165,000 beads per system. The final systems also contained water molecules, counterions, and 150 mM of NaCl.

Simulation protocol

All simulations were carried out using the GROMACS simulation package version 2016.4 (37), with the standard Martini v2.2 simulation settings and parameters (38) as published on the Martini website (available on martini website in the lipidome section: http://www.cgmartini.nl/index.php/force-field-parameters/lipids, with a detailed overview given in http://www.cgmartini.nl/index.php/force-field-parameters/lipids2/350-lipid-details). A short energy minimization procedure was performed using the steepest descent algorithm, with position restraints of 1000 kJ mol−1 nm−2 applied to protein beads, followed by a gradual equilibration procedure whereby position restraints were lowered and limited to only the protein backbone beads. Production runs were carried out using a 20-fs timestep, and weak position restraint was applied to backbone beads (1 kJ mol−1 nm−2). The temperature was kept at 310 K using the velocity rescale thermostat (39), with a time constant for coupling of 1 ps. A 1 bar pressure was applied semi-isotropically to the system and maintained using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat, with a compressibility of 3 × 10−4 bar−1 and a relaxation time constant of 12 ps.

To maintain the spacing between proteins and to decouple lipid-protein interactions from protein-protein contacts, we applied small position restraints on the backbone beads of GPCRs and simulated each system for 30 μs. Analysis presented here, unless stated otherwise, are carried out on the last 5 μs of the simulation trajectories and are mainly focused on lipids within a 7-Å distance cutoff from the protein (and unless otherwise stated, this is the default radius we use).

Analysis

A detailed explanation of the analysis protocol and tools used is available in the Supporting Materials and Methods.

Results

All simulations presented here are carried out using a complex membrane model in which we inserted four copies of each GPCR structure (Fig. 1 D). The membrane model has been described previously and has been applied to study lipid-protein interactions in 10 different proteins, including δOR, which is an opioid GPCR. We used the Martini CG force field to model our systems and the underlying interactions (32). Briefly, an equidistantly placed quartet of each GPCR structure is simulated in a membrane environment composed of 63 different lipid types and stretched in a 40 × 40 nm2 surface area in the lateral dimension. We use the same number density and relative ratios to represent each lipid type as described in our previous work (31). The resulting membrane model has an asymmetric lipid distribution whereby GM and PIP lipids, for instance, are found exclusively in the upper and lower leaflet, respectively.

Figure 1.

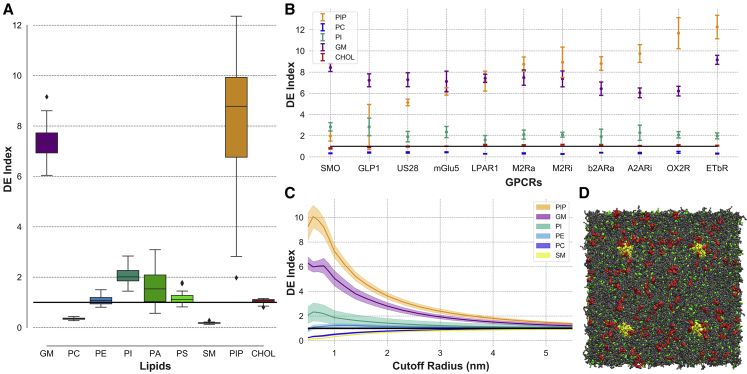

GPCR depletion enrichment (DE) index data as derived from our simulations. (A) Boxplot shows the DE index values for all GPCRs combined. We have grouped lipids according to their headgroup type into GM, PC, PE, PI, PA, PS, SM, PIP, and CHOL lipids, and for each lipid group, we show the three quartile values of the distribution. Data points that fall within a 1.5 interquartile range of the upper and lower quartiles are included in the “whiskers” of the boxplot. Data points that fall outside of this range are plotted individually. (B) DE index values for a selection of GPCRs (error bars are ± SD) are shown. The selection is based on increasing DE index values for PIP lipids. For clarity, if two or more GPCRs show the same range of values, only one is chosen. The full data set is available in the Supporting Materials and Methods. (C) DE index data as a function of cutoff radii from A2ARi are shown (error bars are ± SD). The black line in (A–C) corresponds to DE index of 1. (D) Shown is a snapshot of our system setup at 25 μs with proteins, GM lipids, and cholesterol shown in yellow, red, and green, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

When displaying lipid-protein interactions, for clarity and brevity reasons, we usually limit ourselves to a small sample of GPCRs. There are no hard rules regarding which GPCRs we show in a particular example, and for most cases, they can be substituted with any other structure without altering the message. We do, however, go to great lengths to provide a complete analysis of the lipid-protein interaction profile of all GPCRs, either in the Supporting Materials and Methods or through the accompanying website.

The lipid environment near GPCRs is distinctly different from the bulk membrane composition

We use the average number of lipids around proteins as a function of time and their cumulative average to show convergence of lipid distributions around proteins (Fig. S1). We note that shorter simulation times (<5 μs), at least using the Martini model, may not be adequate to fully capture the interactions of proteins with lipids. This is seen, for example, from the cumulative average number of lipids within 7 Å of proteins, which takes a significant amount of simulation time to reach an apparent equilibrium state. This is most noticeable for lipids that are present in smaller amounts like GM and PIP lipids and are key players in GPCR-lipid interactions. In a few cases, GM lipids take considerably more time to converge (Figs. S1 and S22). We think that using our protocol, a simulation time of around 20–25 μs should be sufficient for this type of systems. Our setup with four approximately independent proteins per simulation provides a statistical control on most results in addition to time-dependent analyses.

To understand how the lipid environment of GPCRs changes during the simulation, we define the Depletion Enrichment (DE) index (Fig. 1 and Tables S2 and S3; (40)). It is a metric that gives us a numerical measure of the tendency of lipids to escape a homogeneous solution and cluster close to (>1) or away from (<1) embedded proteins. Our data clearly show that GPCRs consistently favor a lipid environment that is different from a random or homogenous distribution. Calculated DE index data show that lipid distribution around GPCRs differs markedly from their distribution in the bulk bilayer, either by their enrichment (GM, PI, and PIP lipids) or depletion (PC and SM lipids) in the proximity of embedded proteins (Fig. 1 A). Interestingly, although these results are consistent among all GPCRs studied here, the magnitude of DE indices shows a noticeable variability between different GPCRs (Fig. 1 B). And even though we use a 7-Å distance cutoff in our analysis, the results presented here hold for other cutoff values as well (Fig. 1 C). Fig. 1 C, additionally, highlights the impact of embedded GPCRs on the local membrane environment, in which their effect is “felt” even at 5 nm (50 Å) away (considering that the DE index for each consecutive radius includes lipids from all previous radii, which means its convergence to 1 will be slower and so the GPCR effect on the local membrane may be shorter than 5 nm).

Next, we tested if lipid distributions around class A and non-class A GPCRs differ. We calculated two-sided two-sample t-tests between the average DE indices of class A and non-class A GPCRs. As a control, we performed the same calculations on aminergic and nonaminergic class A GPCRs (Table S5). The results reveal that the distribution of PIP and CHOL, but not GM, lipids differs significantly between class A and non-class A GPCRs but does not differ between aminergic and nonaminergic class A GPCRs (independent of distance cutoff). PE and PS lipids, as well, show a different distribution between class A and non-class A GPCRs.

The average DE index for class A and non-class A GPCRs (with the corresponding 95% confidence interval for the mean) at 7 Å is 9.1 ± 0.6 and 4.9 ± 1.2, respectively, underscoring the higher enrichment of PIP lipids in class A GPCRs (Table S4). Non-class A GPCRs like glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1) and SMO in particular have a much lower enrichment of PIP lipids than other GPCRs. The same calculations for cholesterol yield 1.07 ± 0.02 and 0.89 ± 0.04, respectively, showing a depletion of cholesterol for non-class A GPCRs at 7 Å. Other lipids, like PI and PA, display a higher enrichment close to proteins, but with the exception of SMO, their levels are lower compared to PIP lipids. On the other hand, PC lipids are significantly depleted, whereas PE levels, in general, remain close to one for class A GPCRs but show a higher enrichment for non-class A GPCRs.

The depletion of a particular lipid around a protein, however, is not necessarily a result of their “incompatibility” with each other as it could be a byproduct of the positive enrichment of a different lipid (in the case of PC lipids, this may be the clustering of GM lipids, whereas the depletion of PE lipids may be a result of the enrichment of negatively charged lipids).

Overall, the local environment of GPCRs is characterized by an enrichment of GM lipids in the upper leaflet and negatively charged lipids, particularly PIP lipids, in the lower leaflet relative to the surrounding membrane. These results are consistent in our entire set of GPCR simulations.

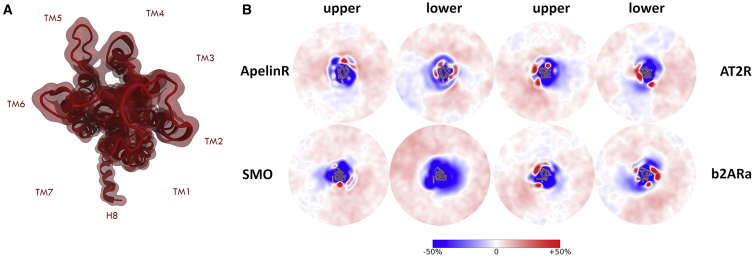

Two-dimensional density profiles reveal a highly localized cholesterol distribution around GPCRs

To visualize GPCR-lipid interactions, we calculated two-dimensional (2D) density maps of cholesterol, fully saturated (FS), and polyunsaturated (PU) lipids around the protein (Fig. 2; Figs. S4–S6) during the last 5 μs of the simulation, separated into upper and lower membrane leaflet densities. Cholesterol density profiles are distinguished by a well-defined localization of cholesterol molecules around proteins, especially when compared to the density profile of PU and FS lipids, hinting at specific interactions of cholesterol with embedded GPCRs. Perhaps one of our most important findings is that we observe specific interactions with cholesterol for all GPCRs simulated. The number and location of these interaction sites differs significantly, however. For instance, we only observe one interaction site for SMO in the upper leaflet, located between helices TM2/3 (ec), and no interaction sites on the lower leaflet side of the receptor. We observe cholesterol interaction sites in both the ec and ic sides of the receptor for the majority of GPCRs simulated. For example, within aminergic GPCRs, we see 3, 4, and 7 interaction sites for dopamine receptor (D3R), histamine receptor, and 5HT1B, respectively. The total number of putative cholesterol interaction sites can vary from one for SMO to eight for cannabinoid receptor (CB1R) and β2ARa. Differences in the number and location of cholesterol binding sites are also observed between different conformational states of the same receptor (Fig. S4). Although our data set for non-class A GPCRs is small and we do see a few putative cholesterol binding sites, overall, we find fewer interaction sites for non-class A GPCRs compared to their class A counterparts, which may explain their differences in the calculated DE indices. In Figs. S13–S16, we give a detailed overview and comparison of GPCR-cholesterol interactions from our simulation results, available crystallographic information, and other MD studies.

Figure 2.

2D density profiles. (A) Orientation of GPCRs within 2D maps: H8 is facing downwards with helices TM1-7 going counterclockwise. (B) Shown is the density profile of three class A GPCRs: apelin receptor (ApelinR), angiotensin receptor (AT2R), and β2AR, as well as class F smoothened (SMO). The GPCRs shown here were chosen to showcase the different number and location of interaction sites as well as being from different subclasses of the GPCR family (peptide, aminergic, and frizzled receptors, respectively). The complete analysis is given in Fig. S4. Density profiles are divided into an upper and lower profile corresponding to the extracellular and intracellular side of the receptor, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

To study the changes induced by GPCRs in the surrounding lipid environment, we grouped lipids into two categories based on the degree of saturation of their lipid tails: lipids that lack any unsaturated bond (FS) and lipids that possess multiple unsaturated bonds (PU). Because we only consider lipids that fall on each edge of the saturation scale, this grouping leaves many lipids unaccounted for, but in exchange, it gives us a clear look into the local membrane environment of GPCRs based on the tail saturation degree. The distribution of FS and PU lipids (Figs. S5 and S6), especially compared to the density profile of cholesterol, is distinctly nonlocal and nonuniform. FS and PU density profiles underscore the GPCR preference for a disorganized lipid environment with PU lipids localized predominantly around the embedded protein. FS lipids, however, seem to be excluded from the protein. This is especially noticeable in the lower leaflet of the membrane. This asymmetrical distribution of lipids, according to their tail saturation degree by the presence of a GPCR, is manifested locally around the protein and is observable by resulting changes in membrane curvature and thickness (Fig. 3).

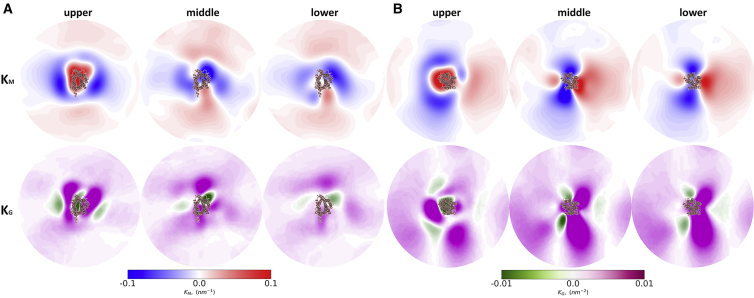

Figure 3.

GPCR curvature analysis. Shown are the mean (KM) and Gaussian (KG) curvature for (A): ApelinR and (B) AT2R, calculated separately for the upper, middle, and lower bilayer plane. For brevity, only the profiles of ApelinR and AT2R from Fig. 2 are shown here. To see this figure in color, go online.

GPCRs induce a unique local membrane environment

Given the changes in the density of FS and PU lipids close to GPCRs in comparison to the surrounding membrane environment, we analyzed how these changes are reflected in the local membrane thickness and curvature. Bulk lipid properties, sometimes also referred to as solvent-like effects (21), is a description of the changes in local membrane physical properties as a result of rearrangements of membrane structural components. The activity of mechanosensitive channels, for instance, is modulated by these effects (41). The importance of bilayer-mediated effects has been recognized for GPCRs as well, most notably for rhodopsin (10) and 5HT1A (26). To gain a deeper understanding of this, we analyzed the membrane thickness as well as the mean and Gaussian curvature of our systems (Fig. 3; Figs. S7–S9).

To our surprise, even though GPCRs share a conserved helical core, the subtle structural differences between them seem to be sufficient to induce different thickness and curvature profiles. A feature that we observe among some GPCR-induced membrane curvatures, especially in the upper leaflet, is a positive mean curvature in and around the protein insertion point with a steep change to negative mean curvature in the surrounding membrane environment. GPCR thickness and curvature profiles highlight the GPCR-induced perturbations in the local membrane environment. In the following sections, we analyze specific GPCR-lipid interactions by focusing on cholesterol and PIP lipids.

GPCRs interact specifically with PIP lipids on the intracellular surface

PIP lipids are negatively charged lipids located exclusively in the lower leaflet. Unlike cholesterol, they only account for a small fraction of membrane lipids (around 0.7%). Despite this, or perhaps because of it, they have repeatedly been shown to form specific interactions with membrane proteins (e.g., receptor tyrosine kinases) (31,42). PIP lipids may modulate key functional aspects of protein activity, and considering their low quantities, they may act as modulators of protein activity. Although experimental data are lacking, GPCR-PIP lipid interactions have recently been highlighted with respect to three GPCRs: β1AR, NTSR1, and A2AR. Yen et al. (25) show compelling evidence from combined experimental and computational methods that PIP lipids stabilize the active state of these GPCRs as well as increase its coupling selectivity to G proteins. Active state stabilization by PIP lipids is also noted by Song et al. (19). MD simulations point to the possibility of such interactions being present in other GPCRs as well. To test this hypothesis and gain further insight into this aspect of GPCR-lipid interactions, we analyzed our set of GPCRs for potential interactions with PIP lipids (Fig. 4).

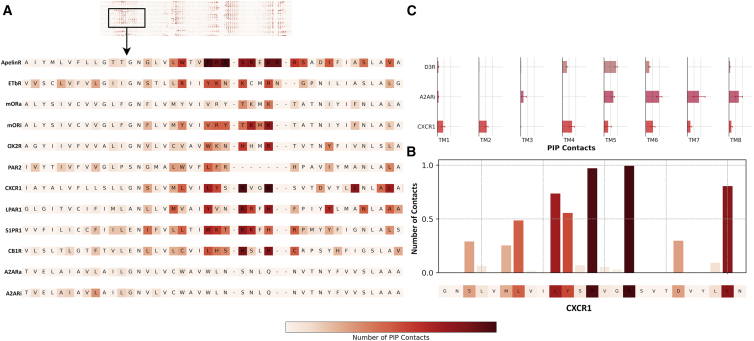

Figure 4.

Sequence heatmaps of GPCR-PIP lipid interactions. (A) Shown is a scaled-down image of all GPCR heatmaps and a zoomed-in view of the TM1-ICL1-TM2 interface for a selection of GPCRs showing the increase in the number of contacts of PIP lipids with charged residues in a White-Red scale. (B) Bar graph of the number of contacts with PIP lipids with CXCR1 TM1-ICL1-TM2 residues is shown. (C) Normalized bar graph presentation of the involvement of each TM helix for three selected GPCRs (D3R, A2ARi, and CXCR1) is shown. Error bars are ± SD. We did not apply selection criteria when choosing the GPCRs to show here, and for each part of the figure, a complete analysis is provided in the Supporting Materials and Methods covering all GPCRs (e.g., Fig. S19 contains the full sequence alignment highlighted here in subplot Table S4. Mean and 95% Confidence Intervals for All DE Indices Corresponding to Four Different GPCR Classifications, Table S5. p-Values Calculated from a Two Sample T-test Comparing the Average DE Indices of Class A versus Non-Class A GPCRs, as Well as Aminergic vs Non-Aminergic Class A GPCRs, the Control, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material). To see this figure in color, go online.

Indeed, we observe a close relationship between GPCRs and PIP lipids in our simulations. For each structure, we find several well-defined and stable interactions with PIP lipids. Starting from the upper leaflet, GPCRs transverse the bilayer seven times. Each turn, depending on the side, is formed by extracellular or intracellular loops. PIP lipids, being confined in the lower membrane leaflet, interact with GPCRs mainly, although not exclusively, at these turning points: TM1-ICL1-TM2, TM3-ICL2-TM4, TM5-ICL3-TM6, and TM7/8. Interaction of PIP lipids with the first of these interfaces, TM1-ICL1-TM2, for a selection of GPCRs is shown in Fig. 4, and the complete set of results in provided in Figs. S10, S18, and S19. Because of GPCR ICLs extension outside of the membrane and into an aqueous environment, their sequences are lined with charged residues (arginine and lysine) that we identify as the key residues involved in establishing and maintaining interactions with PIP lipids through charge-charge interactions. For chemokine receptor (CXCR1), for instance, interactions with PIP lipids are mediated by two arginine residues (Fig. 4 B), with similar interactions being observed for most other GPCRs as well (Fig. 4 A), although not for A2AR because it lacks charged residues at this interface. Additionally and somewhat surprisingly, this interaction with PIP lipids at the TM1-ICL1-TM2 interface is lacking for β2AR (in both of its conformational states) and D3R. Yen et al., in their study of β1AR, noted PIP lipid interactions with the receptors TM5, TM6, and TM7 but not TM1 and TM2 helices. These results imply that although GPCR-PIP lipid interactions are mediated by charge-charge interactions, the presence of charged residues alone is not a sufficient indicator to guarantee interaction. The intracellular loop plus the incoming and outgoing TM helices may constitute the interacting interface that ensures a specific binding of PIP lipids.

When we look at the involvement of different TMs in establishing and maintaining contacts with PIP lipids, we see that GPCRs differ noticeably in the localization of PIP contacts and the extent of the involvement of TM helices in maintaining these interactions (Fig. 4 C). CXCR1, for instance, displays a higher number of contacts with TM helices 1, 2, 4, and 6. D3R, on the other hand, displays a higher localization of PIP lipids at the distal part of TM5. Similarly, A2ARi is characterized by a very different involvement of TM helices, namely TMs 6, 7, and 8. These three examples show the different ways PIP lipids interact with GPCRs (for the complete results, see Fig. S10).

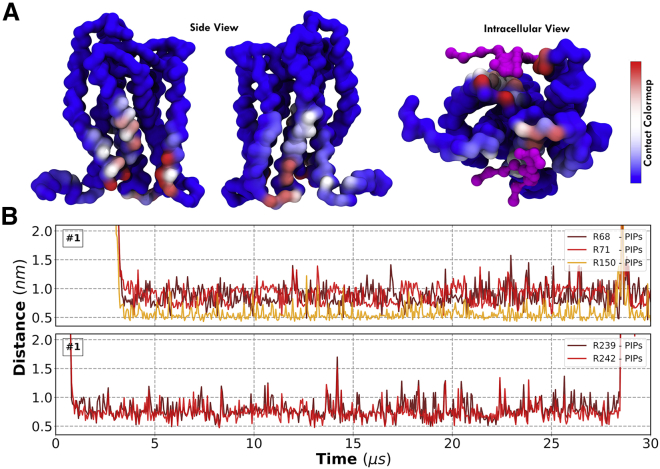

We selected CXCR1 as an example to showcase its interaction with PIP lipids in further detail. We identify two PIP interaction sites or hotspots (Figs. 4 and 5). The first one is formed by three helices (TM1, TM2, and TM4) and binds PIP lipids with greater affinity than the second hotspot, which is located on the interface between ICL3 and TM6. Arginine and lysine residues at the intracellular part of TM1 and TM4 helices interact with the charged headgroup of PIP lipids, thus forming strong interactions that are maintained throughout the simulation trajectory; we show this by calculating the center-of-mass distances between contacting PIP lipids and Arg68, Arg71, and Arg150 residues of CXCR1 (Figs. 5 B and S11).

Figure 5.

CXCR1-PIP lipid interactions. (A) Shown is a protein surface presentation of the number of contacts with PIP lipids (increasing number of contacts corresponds to Blue-White-Red color change) viewed in the plane parallel to the bilayer (showing helices one to four and five to eight on the left and right figure, respectively) and normal to the bilayer (showing example snapshots of PIP lipids—in magenta—bound to the protein). (B) Center-of-mass distances between key residues in each interaction site are identified with PIP lipids. For this particular case, interactions, once formed, are maintained throughout the duration of the trajectory. To see this figure in color, go online.

Three key findings from our simulations with respect to GPCR-PIP lipid interactions are 1) GPCR interactions with PIP lipids are present in all GPCRs simulated, including non-class A GPCRs; 2) they are specific to PIP lipids in the sense that the binding sites are generally inert to other lipids (interactions with other charged lipids are observed, but they are easily displaced by PIPs); and 3) the prevalence of interaction sites (measured as number of contacts), their relative strength (measured as duration of contacts), and their localization vary considerably among different GPCRs. We have already known that the location of identified cholesterol hotspots depends on the receptor; here, we show that the same is true for GPCR-PIP lipid interactions.

Cholesterol interactions are a unique identifier for GPCRs

MD simulations either alone or in tandem with experiments have elucidated cholesterol interaction sites for several GPCRs: β2AR, A2AR, SMO, δOPR, μOR, rhodopsin, and 5HT1A (see Introduction). Understanding GPCR-cholesterol interactions in a GPCR-wide context has, however, been challenging. Why and how do cholesterol molecules interact with GPCRs? One mechanism that has been proposed to underlie GPCR-cholesterol interactions is the characterization of cholesterol binding motifs (i.e., the CRAC and CARC motifs) (43). These are 5–13 aa-long sequences that exhibit a high binding affinity for cholesterol. These motifs indeed show a higher propensity for cholesterol interactions (44) and have been found to form the interface of putative cholesterol interaction sites in GPCRs (43). Because of their somewhat indiscriminate definition, however, it is difficult to properly assess their importance and relevance. To address these issues as well as gain a deeper insight into the “how” part of the GPCR-cholesterol question, we present a detailed analysis of our data with respect to cholesterol interactions.

For each simulated GPCR structure, we identify several sites with an increased cholesterol localization (measured as number of contacts and 2D density profiles). These interaction sites, however, do not have the same binding strength for cholesterol, and when they are studied further using other computational tools, usually only a few of them display a consistent interaction with cholesterol. This is why in our calculations we simultaneously consider the number of contacts with cholesterol as well as their duration, resulting in a much clearer picture of GPCR-cholesterol interactions (Figs. S13–S15).

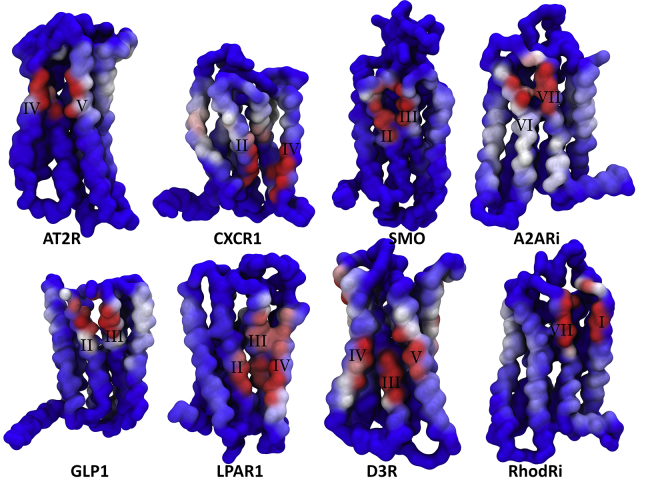

We show interactions with cholesterol for a small subset of GPCRs in Fig. 6 (a detailed comparison and complete analysis is given in Figs. S4, S13–S16, S20, and S21). Each GPCR structure displays at least one site of pronounced affinity for cholesterol binding that is stable and usually maintained throughout the simulation, and on average, we find five to seven interaction sites per GPCR, one to three of which are noted for the stability of the interaction.

Figure 6.

GPCR-cholesterol interaction for a sample of eight GPCRs shown as a surface presentation of cholesterol contact durations. Color scale (red-white-blue) represents an increase in the duration of cholesterol contacts (similar to Fig. 5). A larger set of GPCRs, including a detailed comparison between contact duration and contact number as the visualization metric, is given in the Supporting Materials and Methods. To see this figure in color, go online.

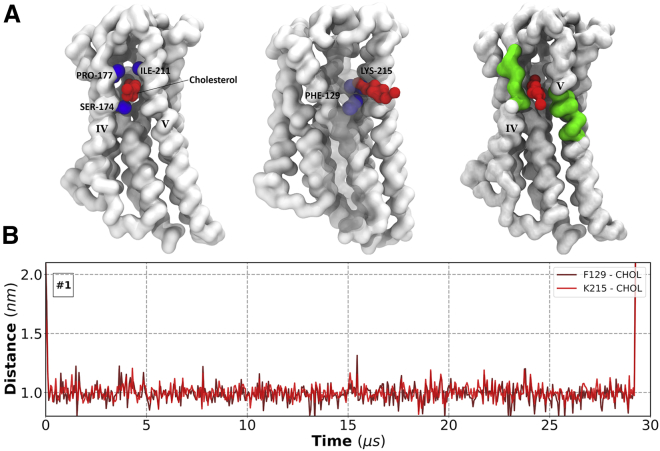

The binding of cholesterol to AT2R is an interesting example displaying the interaction between GPCRs and cholesterol (Fig. 7 A). Helices TM4 and TM5 on the extracellular side of the receptor are spaced just sufficiently far apart to accommodate one cholesterol molecule in between them. The entrance to this crevice is made of hydrophobic residues (Pro-177 and Ile-211), and we consistently find a cholesterol molecule inserted inside this crevice, interacting with a phenylalanine (Phe-129) residue in TM3. This binding is mediated by interactions with the hydroxyl-containing (ROH) bead of cholesterol and Lys-215 (K5.42) in TM5 (Fig. 7 B). This interaction is present in all four copies of AT2R, in one case persisting for the last 29 μs in the 30 μs simulation. Although we cannot observe complete insertion of cholesterol because of limited conformational flexibility of the proteins in coarse-grained simulations, lipid entry in GPCRs has been noted before in atomistic simulations for CB2R (45), opsin (46), and A2AR (30). Analysis for all protein copies is shown in Fig. S12.

Figure 7.

Cholesterol binding to angiotensin receptor (AT2R). (A) Simulation snapshots show a cholesterol (red) molecule buried inside helices TM4 and TM5 of AT2R (white). Residues lining up the entrance to this crevice are shown as blue spheres; cholesterol’s hydroxyl-containing ROH bead interacts with Lys-215 (K5.42). TM4 is left transparent for clarity; CRAC and CARC motifs present in TM4 and TM5, respectively, are colored in green. (B) Shown are center-of-mass distance calculations between cholesterol and Phe-129 (3.37) and Lys-215 (K5.42), respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

An important feature of AT2R-cholesterol interaction is that TM4 contains a CRAC motif and TM5 contains a CARC motif, both lining up the cholesterol entry gateway. Analyzing our data in the context of cholesterol binding motifs reveals a more complicated story, however. Indeed, we find CRAC and CARC motifs to take part in forming cholesterol interaction sites for several GPCRs: A2AR, ApelinR, AT2R, CB1R, CXCR1, D3R, endothelin (ETBR), GLP1, GlucagonR, protease-activated receptor, and lysophospholipid sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor, showing that these motifs are capable and do bind cholesterol. When they are present, CRAC and CARC motifs constitute one way cholesterol may bind to GPCRs. In the context of all simulations performed, however, we find that the mere presence of these motifs is insufficient to determine the existence of cholesterol hotspots, regardless of their location within TM helices. This is because we find many stable GPCR-cholesterol interactions that are not mediated by these motifs and even plenty of such motifs that do not bind cholesterol at all. We further note that the number of CRAC/CARC motifs in GPCRs vary strongly, from three on A2AR (two of which overlap with one another) up to 13 for mGlu5 (nine CRAC and four CARC motifs). Coincidentally, the two TM helices of mGlu5 that feature the highest localization of cholesterol do not do it through any of those motifs. On the other hand, other GPCRs, like CXCR1 and xphinboxind 1-phosphate receptor, do bind cholesterol through these motifs at their most pronounced interaction site. Similar comments about these motifs have also been made in the literature (11,47,48).

GPCR-lipid interactions are dependent on the conformational state of the receptor

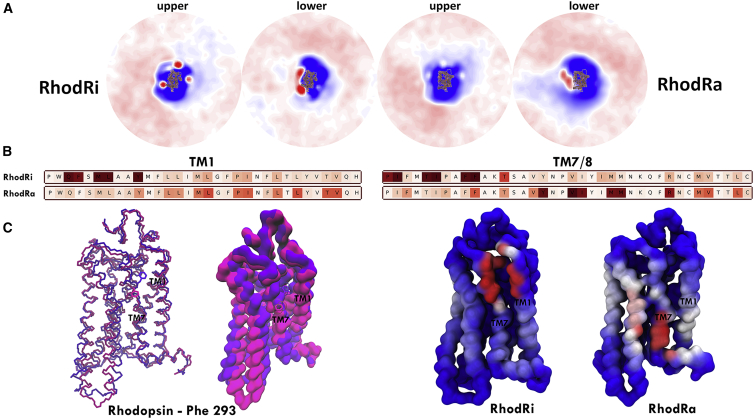

MD simulations of β2AR (18) show that cholesterol reduces the conformational landscape sampled by the receptor through specific lipid-protein interactions rather than cholesterol’s order-inducing effect on membrane lipids. Simulations of μOR (28) and A2AR (19) using CGMD reveal cholesterol interactions that vary based on the conformational state of the receptor. We reaffirm these findings in the case of μOR and A2AR and show that β2AR, M2R, and RhodR as well interact with cholesterol in a conformation-dependent manner. Specific interactions with cholesterol for rhodopsin have been noted before, with one of the interaction sites identified being located at the TM7/1 helix (22), and rhodopsin interactions with docosahexaenoic acid have been shown to depend on the conformational state of the receptor (21).

Rhodopsin-cholesterol interactions differ significantly depending on the conformational state of the receptor (Fig. 8 A). We observe three interaction sites on the extracellular side of RhodRi that are largely missing in RhodRa. In terms of the duration of contacts, TM7/1 is the most prominent interaction site with cholesterol for RhodRi. Sequence heatmaps for the duration of contacts show that this site is completely absent in RhodRa (Fig. 8 B). What difference between the structures of RhodRi and RhodRa accounts for this change? Phe-293 is the key residue modifying rhodopsin-cholesterol interactions. Phe-293 faces the inside of the receptor in RhodRi, allowing cholesterol molecules to easily access the TM7/1 interface, and assists in binding cholesterol. In RhodRa, it, however, faces away from the receptor and thus unavailable to interact with cholesterol. For RhodRa, on the other hand, we observe a cholesterol interaction site on the distal part of TM7, which is not present in RhodRi.

Figure 8.

Cholesterol interactions with RhodRi and RhodRa. (A) 2D density profiles for rhodopsin are shown. (B) Sequence heatmap of the duration of contacts for TM1 and TM7/8 helices for RhodRi and RhodRa is shown. (C) Comparison of the position of Phe 293 in RhodRi (violet) and RhodRa (magenta) and the resulting change in their cholesterol interaction profile is shown. Color gradients are as described previously. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Currently, we know 323 structures divided over 61 different GPCRs (49). The vast majority of these structures belong to class A GPCRs, with class B, C, and F only accounting for 37 of the structures. Out of all class A GPCR structures, almost half (132 or 45%) belong to only four GPCRs: β1AR (24), β2AR (22), A2AR (45), and rhodopsin (41). MD simulations, which rely on the availability of initial protein coordinates, reflect this, with the majority of articles being published on these GPCRs as well. Our set of structures simulated spans 23 (or ∼40% of the 61) different GPCRs and allows us to characterize the lipid interaction profile of each structure individually but also understand lipid-protein interactions in a GPCR-wide context.

We analyzed GPCR-lipid interactions with single lipids as well as by grouping lipids based off their headgroup type and lipid tail saturation level. The results show that GPCRs are characterized by a unique lipid-protein interaction profile that is not only GPCR dependent but also conformation dependent. We consistently see GPCRs interacting specifically with cholesterol, GM, and PIP lipids in an environment that is strikingly different from the surrounding membrane. We observe that, for the most part, GPCRs share the type of lipid group but not the degree that it is enriched/depleted and that the local membrane environments of class A GPCR and non-class A GPCRs differ.

We analyzed all GPCR crystal structures for interactions with cholesterol and found that 20% of GPCR crystal structures solved (64 out of 323) have been co-crystallized with cholesterol. Of them, 38 (59%) are A2AR (27) and β2AR (11) structures. Interestingly, none of the β1AR and rhodopsin structures solved contain bound cholesterol molecules, despite them being solved at roughly equal numbers to β2AR and A2AR, respectively. Serotonin receptors (5HT2A and 5HT2B) account for an additional nine structures. Of all structures that have been crystallized with cholesterol, the only ones we did not simulate are thromboxane A2 and P2Y receptors. We give a detailed comparison of our simulation results with available experimental data in Figs. S13–S16. A summary of cholesterol interaction sites from crystallographic data shows that the interaction sites appearing more than once are TM1-4 (ic), TM1-2 (ec), TM4-5 (ic), TM6-7 (ec), and TM8/1. These are interaction sites that we also consistently observe in our simulations, and based on the number and duration of contacts with cholesterol, we observe the TM2/3 (ec), TM6-7 (ec), and TM8/1 (ic) interaction sites more frequently than TM1/4 (ic), TM5-6 (ec), TM6-7 (ic), and TM7/1 (ec). Other sites like TM1-2 (ec), TM4-5 (ec), and TM4-5 (ic) occur even less frequently.

Overall, GPCRs express two larger (TM1-4 and TM5-8/1) and two smaller (TM4-5 and TM7-8/1) surfaces for cholesterol binding, and each of these surfaces can bind cholesterol in either the extracellular or ic side (Fig. S17). For instance, binding on the TM1-4 surface can occur on the extracellular side between TM1-2 and TM2-3 (albeit to a much lesser extent) and on the intracellular side between TM1-2/4. The other large surface (TM5-8/1) displays several binding sites for cholesterol with the most prominent, in our simulations, being the TM6/7 (ec) interface. The TM6-7 (ec) interface in particular seems to occur on many class A GPCRs. We consistently find a high cholesterol occupancy at this site sufficient to accommodate two cholesterol molecules (similar to what is observed in crystal structures). The hydrophobic residue (usually either valine, leucine, or isoleucine) in the 6.46 position is seen to interact preferably with cholesterol for many class A GPCRs. Non-class A GPCRs (SMO, GLP1, calcitoninR), however, do not seem to display this interaction site. In terms of GPCR ligand binding and functional activity, cholesterol can either act as a positive or negative modulator (30). Guixà-González et al. (30) summarized the relevant literature on this issue, highlighting the receptor-dependent activity of cholesterol. Considering that cholesterol enhances the function capabilities of β2AR and μOR and diminishes that of rhodopsin, we speculate that if the TM6-7 (ec) interaction site, which we do observe for the former but do not for the latter, may be at least partly responsible for it. Although the nature of our simulation protocol hinders us from making any definitive statements, we do think this issue merits further investigation.

In their 2008 study, Hanson et al. (50) defined the cholesterol consensus motif, which differs from CRAC/CARC motifs in that it is a spatial arrangement of residues rather than a linear sequence. They defined it in the context of β2AR and estimated that the motif exists in 21% of human class A GPCRs. Our results strongly point toward a cholesterol binding profile of GPCRs that involves residues from multiple helices. The majority of interactions with cholesterol that we observe, especially those that are present for a majority of the simulation time, are found at the interfaces between two or three helices and often also supported by residues from extracellular and intracellular loops. Even cholesterol interactions that predominantly involve TM1 are supported by interactions of cholesterol (ROH bead) with H8 residues.

Based on our simulations, it appears that cholesterol binding is conditioned on two key components: a hydrophobic residue environment that stabilizes cholesterol and a geometric compatibility between cholesterol and the protein interface, which accommodates its ring structure. Shielding of the cholesterol hydroxyl group (“ROH” bead in our system) from the hydrophobic environment is also important, but we find that nearby lipids help with it, and as such, charged residues are not an essential requirement. Cholesterol binding may occur in the absence of aromatic residues; the presence of aromatic residues, however, is observed very frequently, and their orientation may serve as a determining factor for cholesterol binding as we observe for rhodopsin (Fig. 8).

CRAC/CARC motifs may be unique in that they are linear sequences that fulfill all these requirements themselves, but usually, we see two or three TM helices working in concert to bind cholesterol.

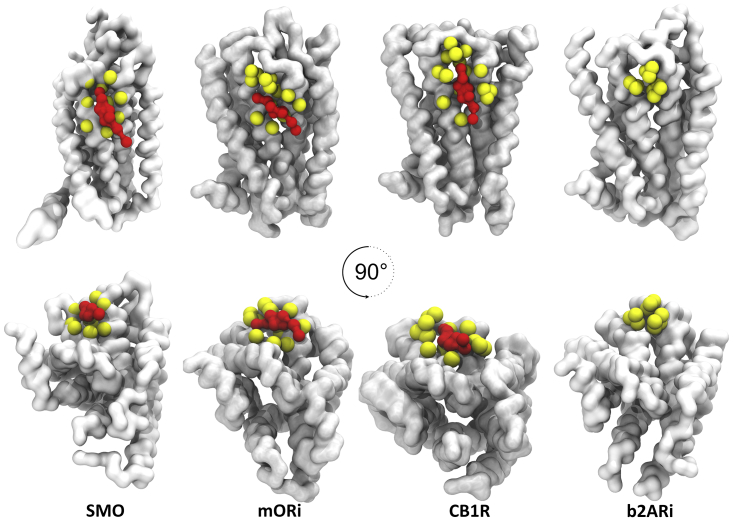

Fig. 9 highlights the TM2/3 (ec) interface for four different GPCRs: three (SMO, μOri, and CB1R) bind cholesterol specifically at that site, and the fourth (β2ARi) does not. The reason for this is that residues comprising the TM2/3 (ec) interface for β2AR do not provide the “geometric compatibility” necessary for binding. SMO, μORi, and CB1R residues at the TM2/3 (ec) interface form an “interacting bed” that enables cholesterol binding. The spacing of residues is also an important factor determining the interaction strength. For these proteins, the binding strength (measured as duration of contacts) is SMO ≥ CB1R > μORi.

Figure 9.

Overview of cholesterol binding sites. We show cholesterol binding at the TM2/3 (ec) interface for three GPCRs: SMO, μORi, and CB1R. For comparison, the same interface is shown for β2ARi in which this interaction site is missing. Proteins are shown in white, cholesterol are shown in red, and residues comprising the TM2/3 (ec) interface are shown in yellow. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also find PIP lipids are closely involved in lipid-protein interactions with GPCRs. PIP lipids and in particular interactions with PtdIns(4,5)P2, confer stability to GPCRs and increase their GTPase activity (25). Mass spectrometry experiments in tandem with computer simulations showed that PIP2 lipids stabilize the active state of GPCRs and act as allosteric modulators (25). This effect seems to be higher for PIP2 than for PA, PI, PS, and other PIP lipids, and the cytoplasmic side of GPCRs may contain PIP binding hotspots. MD simulations in the case of A2AR reaffirm the importance of PIP lipids interactions (19). Here, we confirm these findings and furthermore extend them to the whole GPCR family. We also find that PIP lipid interactions, although being mediated by charge interactions, differ among GPCRs. Taking all simulations into account, we see that PIP lipids bind at four different sites on GPCR surfaces (TM1-ICL1-TM2, TM3-ICL2-TM4, TM5-ICL3-TM6, and TM7/8) but GPCRs differ in how and which of these sites are utilized. For example, A2AR and β2AR receptors do not make any noticeable contacts through their TM1-ICL1-TM2 interface, whereas many other GPCRs do. The number of PIP lipids bound to each of these sites varies among GPCRs simulated as well as does the longevity of these interactions. For instance, CXCR1 binds PIP lipids for the whole simulation time (Fig. 5); SMO does so only for a fraction of it.

In our simulations, we have used the Martini model to study GPCR-lipid interactions, and as such, all underlying assumptions on which the model is built as well as its advantages and shortcomings are carried forward to our results. Because of the nature of the model, we lack the resolution to describe in detail the lipid-binding sites identified as well as provide a quantitative measure of their strength. When we refer here to the strength of a binding site, we base it on the number and duration of lipid contacts. That is, however, not a replacement for carrying out all-atom simulations and free energy calculation methods. Furthermore, to analyze lipid-protein interactions in a GPCR-wide context, we used the same system setup for all structures. The disadvantage of this approach is that our complex membrane model does not represent the “natural” environment to any GPCR in particular. This is, however, a problem that all MD simulation studies of membrane proteins face (12).

Our membrane model contains three different PIP lipids in equal amounts (PIP1, PIP2 and PIP3), and we observe each of them interacting with GPCRs. Current experimental evidence (25), however, shows PIP2 to be of higher preference and acting in a structure-specific manner compared to other lipid types. Although we do observe PIP2 interactions to occur more frequently than PIP1, we lack either the resolution or the sampling to address this question properly. In our model, we also lack any GPCR effector proteins and as such cannot comment on how GPCR-PIP lipid interactions affect coupling to G proteins. We do note, however, that PIP lipid interactions with the active and inactive state of GPCRs simulated here differ from each other (Fig. S18). More detailed simulations at a higher resolution coupled with free energy calculation methods are, however, necessary to fully characterize these details.

Our results represent a large-scale attempt to understand lipid-GPCR interactions at the family level of classification. To this end, we have uncovered that GPCRs, despite sharing common structural features and a conserved helical core, nevertheless create a unique local membrane environment and interact with lipids in a GPCR conformation-specific manner. Lipids have been implicated as either affecting or directly controlling the activity of many proteins, even acting as allosteric modulators (11). Humans express over 800 different GPCRs and the ligand binding landscape of GPCR is in the thousands. Yet signaling as a response to ligand binding is mediated by only four Gα families (2). Flock et al. (2) proposed the existence of a “selectivity barcode” at the GPCR-G protein interface that could enable this large array of GPCRs to maintain their specific response by only coupling to a few effector proteins. GPCR-lipid interactions may present another such barcode that characterizes GPCRs and helps in retaining their specific response.

Conclusions

We observe specific interactions with lipids for all GPCRs simulated. The lipid types we observe to consistently and most prominently form specific and long-lasting interactions with GPCRs are cholesterol and PIP lipids. Analysis of these interactions, however, reveal that although cholesterol interactions depend on the existence of a hydrophobic environment and aromatic residues to stabilize its ring structure, interactions with PIP lipids rely on the existence of charged residues lining up the sequence of intracellular loops.

When we compare the cholesterol interaction profiles between different GPCRs, or even different conformational states of the same GPCR, we find some interaction sites that are quite common (e.g., TM6-7 (ec), TM2/3 (ec)) and others that occur rarely (e.g., TM4-5 (ic)). In the cases in which the same interaction site is observed to bind cholesterol for multiple GPCRs, we still see differences in the binding strength of cholesterol and its binding conformation (Fig. 9).

Accounting for the lipid type, the different interaction sites, and their binding strength, as well as the resulting changes in bilayer thickness and curvature, we conclude that the GPCR-lipid interaction profile constitutes a defining feature for each GPCR structure.

Along with the main text, we provide a webpage (https://bisejdiu.github.io/GPCR-lipid-interactions) in which users can interactively view interactions of GPCRs with cholesterol and PIP lipids represented as three-dimensional densities as well as the calculated thickness and curvature profiles.

Author Contributions

B.I.S. and D.P.T. designed the research. B.I.S. performed the research and analyzed the data. B.I.S. and D.P.T. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada with further support from the Canada Research Chairs program. Calculations were performed on Compute Canada facilities, funded by the Canada Foundation for Innovation and partners.

Editor: Alemayehu Gorfe.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.03.008.

Supporting Citations

References (51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

Aminergic, non-Aminergic Class A, Class A and non Class A GPCRs. Data are shown for the following distance cutoffs (in nm): 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0

References

- 1.Isberg V., Mordalski S., Gloriam D.E. GPCRdb: an information system for G protein-coupled receptors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D356–D364. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flock T., Hauser A.S., Babu M.M. Selectivity determinants of GPCR-G-protein binding. Nature. 2017;545:317–322. doi: 10.1038/nature22070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manglik A., Kruse A.C. Structural basis for G protein-coupled receptor activation. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5628–5634. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gimpl G. Interaction of G protein coupled receptors and cholesterol. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2016;199:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song Y., Kenworthy A.K., Sanders C.R. Cholesterol as a co-solvent and a ligand for membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2014;23:1–22. doi: 10.1002/pro.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sengupta D., Chattopadhyay A. Molecular dynamics simulations of GPCR-cholesterol interaction: an emerging paradigm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parrill A.L., Tigyi G. Integrating the puzzle pieces: the current atomistic picture of phospholipid-G protein coupled receptor interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1831:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mondal S., Khelashvili G., Weinstein H. Not just an oil slick: how the energetics of protein-membrane interactions impacts the function and organization of transmembrane proteins. Biophys. J. 2014;106:2305–2316. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soubias O., Gawrisch K. The role of the lipid matrix for structure and function of the GPCR rhodopsin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soubias O., Teague W.E., Jr., Gawrisch K. Rhodopsin/lipid hydrophobic matching-rhodopsin oligomerization and function. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1125–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corradi V., Sejdiu B.I., Tieleman D.P. Emerging diversity in lipid-protein interactions. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:5775–5848. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrink S.J., Corradi V., Sansom M.S.P. Computational modeling of realistic cell membranes. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:6184–6226. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enkavi G., Javanainen M., Vattulainen I. Multiscale simulations of biological membranes: the challenge to understand biological phenomena in a living substance. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:5607–5774. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muller M.P., Jiang T., Tajkhorshid E. Characterization of lipid-protein interactions and lipid-mediated modulation of membrane protein function through molecular simulation. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:6086–6161. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng X., Smith J.C. Biological membrane organization and cellular signaling. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:5849–5880. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genheden S., Essex J.W., Lee A.G. G protein coupled receptor interactions with cholesterol deep in the membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2017;1859:268–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cang X., Du Y., Jiang H. Mapping the functional binding sites of cholesterol in β2-adrenergic receptor by long-time molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:1085–1094. doi: 10.1021/jp3118192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manna M., Niemelä M., Vattulainen I. Mechanism of allosteric regulation of β2-adrenergic receptor by cholesterol. eLife. 2016;5:e18432. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song W., Yen H.Y., Sansom M.S.P. State-dependent lipid interactions with the A2a receptor revealed by MD simulations using in vivo-mimetic membranes. Structure. 2019;27:392–403.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouviere E., Arnarez C., Lyman E. Identification of two new cholesterol interaction sites on the A2A adenosine receptor. Biophys. J. 2017;113:2415–2424. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salas-Estrada L.A., Leioatts N., Grossfield A. Lipids alter rhodopsin function via ligand-like and solvent-like interactions. Biophys. J. 2018;114:355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horn J.N., Kao T.C., Grossfield A. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics provides insight into the interactions of lipids and cholesterol with rhodopsin. In: Filizola M., editor. G Protein-Coupled Receptors - Modeling and Simulation. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 796. Springer-Verlag; 2014. pp. 75–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teague W.E., Jr., Soubias O., Gawrisch K. Elastic properties of polyunsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines influence rhodopsin function. Faraday Discuss. 2013;161:383–395; discussion 419–459.. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20095c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawaliby R., Trubbia C., Govaerts C. Allosteric regulation of G protein-coupled receptor activity by phospholipids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:35–39. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen H.Y., Hoi K.K., Robinson C.V. PtdIns(4,5)P2 stabilizes active states of GPCRs and enhances selectivity of G-protein coupling. Nature. 2018;559:423–427. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutierrez M.G., Mansfield K.S., Malmstadt N. The functional activity of the human serotonin 5-HT1A receptor is controlled by lipid bilayer composition. Biophys. J. 2016;110:2486–2495. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta D., Chattopadhyay A. Identification of cholesterol binding sites in the serotonin1A receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:12991–12996. doi: 10.1021/jp309888u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marino K.A., Prada-Gracia D., Filizola M. Impact of lipid composition and receptor conformation on the spatio-temporal organization of μ-opioid receptors in a multi-component plasma membrane model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016;12:e1005240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedger G., Koldsø H., Sansom M.S.P. Cholesterol interaction sites on the transmembrane domain of the hedgehog signal transducer and class F G protein-coupled receptor smoothened. Structure. 2019;27:549–559.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guixà-González R., Albasanz J.L., Selent J. Membrane cholesterol access into a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14505. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corradi V., Mendez-Villuendas E., Tieleman D.P. Lipid-protein interactions are unique fingerprints for membrane proteins. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018;4:709–717. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wassenaar T.A., Ingólfsson H.I., Marrink S.J. Computational lipidomics with insane: a versatile tool for generating custom membranes for molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manna M., Kulig W., Vattulainen I. How to minimize artifacts in atomistic simulations of membrane proteins, whose crystal structure is heavily engineered: β2-adrenergic receptor in the spotlight. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3432–3445. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ingólfsson H.I., Melo M.N., Marrink S.J. Lipid organization of the plasma membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu R.-X., Ingólfsson H.I., Tieleman D.P. Ganglioside-lipid and ganglioside-protein interactions revealed by coarse-grained and atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:3262–3275. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b07142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Jong D.H., Singh G., Marrink S.J. Improved parameters for the martini coarse-grained protein force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:687–697. doi: 10.1021/ct300646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu R.-X., Baoukina S., Tieleman D.P. Cholesterol flip-flop in heterogeneous membranes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:2064–2070. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pliotas C., Dahl A.C., Naismith J.H. The role of lipids in mechanosensation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:991–998. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedger G., Sansom M.S., Koldsø H. The juxtamembrane regions of human receptor tyrosine kinases exhibit conserved interaction sites with anionic lipids. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9198. doi: 10.1038/srep09198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jafurulla M., Tiwari S., Chattopadhyay A. Identification of cholesterol recognition amino acid consensus (CRAC) motif in G-protein coupled receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;404:569–573. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fantini J., Di Scala C., Barrantes F.J. A mirror code for protein-cholesterol interactions in the two leaflets of biological membranes. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21907. doi: 10.1038/srep21907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurst D.P., Grossfield A., Reggio P.H. A lipid pathway for ligand binding is necessary for a cannabinoid G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:17954–17964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park J.H., Scheerer P., Ernst O.P. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature. 2008;454:183–187. doi: 10.1038/nature07063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee A.G. A database of predicted binding sites for cholesterol on membrane proteins, deep in the membrane. Biophys. J. 2018;115:522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee A.G. Interfacial binding sites for cholesterol on G protein-coupled receptors. Biophys. J. 2019;116:1586–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jianyi Y., and Z. Yang. GPCR-EXP: a database for experimentally solved GPCR structures, https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/GPCR-EXP/.

- 50.Hanson M.A., Cherezov V., Stevens R.C. A specific cholesterol binding site is established by the 2.8 A structure of the human beta2-adrenergic receptor. Structure. 2008;16:897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fantini J., Barrantes F.J. How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:31. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Castro E., Sigrist C.J., Hulo N. ScanProsite: detection of PROSITE signature matches and ProRule-associated functional and structural residues in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Suppl 2):W362–W365. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGibbon R.T., Beauchamp K.A., Pande V.S. MDTraj: a modern open library for the analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1528–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones E., Oliphant T., Peterson P. 2014. SciPy: open source scientific tools for Python. https://www.scipy.org. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seabold S., Perktold J. Statsmodels: econometric and statistical modeling with python. Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference. 2010;2010:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunter J.D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007;9:90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waskom M., Botvinnik O., Quintero E. 2014. Seaborn: statistical data visualization. Seaborn; p. 5. https://seaborn.pydata.org. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rose A.S., Hildebrand P.W. NGL Viewer: a web application for molecular visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W576–W579. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cignoni P., Callieri M., Ranzuglia G. Meshlab: an open-source mesh processing tool. Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference. 2008;2008:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang C., Jiang Y., Xu H.E. Structural basis for molecular recognition at serotonin receptors. Science. 2013;340:610–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1232807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lebon G., Warne T., Tate C.G. Agonist-bound adenosine A2A receptor structures reveal common features of GPCR activation. Nature. 2011;474:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature10136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jaakola V.P., Griffith M.T., Stevens R.C. The 2.6 angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322:1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma Y., Yue Y., Li C. Structural basis for apelin control of the human apelin receptor. Structure. 2017;25:858–866.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H., Han G.W., Cherezov V. Structural basis for selectivity and diversity in angiotensin II receptors. Nature. 2017;544:327–332. doi: 10.1038/nature22035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasmussen S.G., DeVree B.T., Kobilka B.K. Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011;477:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cherezov V., Rosenbaum D.M., Stevens R.C. High-resolution crystal structure of an engineered human beta2-adrenergic G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hua T., Vemuri K., Korde A. Crystal structure of the human cannabinoid receptor CB1. Cell. 2016;167:750–762.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park S.H., Das B.B., Opella S.J. Structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR1 in phospholipid bilayers. Nature. 2012;491:779–783. doi: 10.1038/nature11580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chien E.Y., Liu W., Stevens R.C. Structure of the human dopamine D3 receptor in complex with a D2/D3 selective antagonist. Science. 2010;330:1091–1095. doi: 10.1126/science.1197410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shihoya W., Nishizawa T., Nureki O. X-ray structures of endothelin ETB receptor bound to clinical antagonist bosentan and its analog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shimamura T., Shiroishi M., Iwata S. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature. 2011;475:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chrencik J.E., Roth C.B., Hanson M.A. Crystal structure of antagonist bound human lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1. Cell. 2015;161:1633–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kruse A.C., Ring A.M., Kobilka B.K. Activation and allosteric modulation of a muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature. 2013;504:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nature12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haga K., Kruse A.C., Kobayashi T. Structure of the human M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor bound to an antagonist. Nature. 2012;482:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature10753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang W., Manglik A., Kobilka B.K. Structural insights into μ-opioid receptor activation. Nature. 2015;524:315–321. doi: 10.1038/nature14886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manglik A., Kruse A.C., Granier S. Crystal structure of the μ-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Suno R., Kimura K.T., Tsujimoto H. Crystal structures of human orexin 2 receptor bound to the subtype-selective antagonist EMPA. Structure. 2018;26:7–19.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheng R.K.Y., Fiez-Vandal C., Dekker N. Structural insight into allosteric modulation of protease-activated receptor 2. Nature. 2017;545:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature22309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Choe H.W., Kim Y.J., Ernst O.P. Crystal structure of metarhodopsin II. Nature. 2011;471:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature09789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li J., Edwards P.C., Schertler G.F. Structure of bovine rhodopsin in a trigonal crystal form. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:1409–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hanson M.A., Roth C.B., Stevens R.C. Crystal structure of a lipid G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2012;335:851–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1215904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burg J.S., Ingram J.R., Garcia K.C. Structural biology. Structural basis for chemokine recognition and activation of a viral G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 2015;347:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liang Y.L., Khoshouei M., Sexton P.M. Phase-plate cryo-EM structure of a class B GPCR-G-protein complex. Nature. 2017;546:118–123. doi: 10.1038/nature22327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Song G., Yang D., Stevens R.C. Human GLP-1 receptor transmembrane domain structure in complex with allosteric modulators. Nature. 2017;546:312–315. doi: 10.1038/nature22378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Siu F.Y., He M., Stevens R.C. Structure of the human glucagon class B G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2013;499:444–449. doi: 10.1038/nature12393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doré A.S., Okrasa K., Marshall F.H. Structure of class C GPCR metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 transmembrane domain. Nature. 2014;511:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature13396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang C., Wu H., Stevens R.C. Structural basis for Smoothened receptor modulation and chemoresistance to anticancer drugs. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4355. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shan J., Khelashvili G., Weinstein H. Ligand-dependent conformations and dynamics of the serotonin 5-HT(2A) receptor determine its activation and membrane-driven oligomerization properties. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2012;8:e1002473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Aminergic, non-Aminergic Class A, Class A and non Class A GPCRs. Data are shown for the following distance cutoffs (in nm): 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0