Abstract

Background:

Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene are an important risk factor for Parkinson’s disease (PD). However, most GBA genetic studies in PD have been performed in patients of European origin and very few data are available in other populations.

Methods:

We sequenced the entire GBA coding region in 602 PD patients and 319 controls from Colombia and Peru enrolled as part of the Latin American Research Consortium on the Genetics of Parkinson’s disease (LARGE-PD).

Results:

We observed a significantly higher proportion of GBA mutation carriers in patients compared to healthy controls (5.5% vs 1.6%; OR= 4.3, p = 0.004). Interestingly, the frequency of mutations in Colombian patients (9.9%) was more than two-fold greater than in Peruvian patients (4.2%) and other European-derived populations reported in the literature (40–5%). This was primarily due to the presence of a population-specific mutation (p.K198E) found only in the Colombian cohort. We also observed that the age at onset was significantly earlier in GBA carriers when compared to non-carriers (47.1 ± 14.2 y vs. 55.9 ± 14.2 y; p = 0.0004).

Conclusion:

These findings suggest that GBA mutations are strongly associated with PD risk and earlier age at onset in Peru and Colombia. The high frequency of GBA carriers among Colombian PD patients (~10%) makes this population especially well-suited for novel therapeutic approaches that target GBA-related PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, genetics, Gaucher’s disease, glucocerebrosidase, GBA, Colombia, Peru

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disease arising from the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and other brainstem nuclei. Although the definitive etiological cause of the vast majority of cases is still unknown, PD likely originates from a complex interaction between aging, genetics, and environmental factors.

Genetic studies have identified more than a dozen “causal” genes and over 40 susceptibility loci for PD, highlighting the complexity of this disorder [1]. Among the susceptibility loci, mutations in the glucocerebrosidase (GBA) gene, which cause autosomal recessive Gaucher’s disease (GD), are the strongest risk factors for PD and confer a 3–6 fold increase in PD risk [2, 3]. However, mutation frequencies and distribution vary greatly between populations. For example, p.L444P (rs421016) and p.N370S (rs76763715) are the most common mutations in most populations, however the combined frequency of these two mutations ranges from approximately 15% of PD patients and 3% of controls among Ashkenazi Jews, to 3% of PD patients and less than 1% of controls in non-Ashkenazi Jewish populations [2]. Additionally, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and a meta-analysis of several GWAS showed that a common GBA polymorphism (p.E326K, rs2230288) significantly increases PD risk [4], despite the fact that is not considered “pathogenic” because it does not cause GD [5]. PD patients who carry GBA pathogenic mutations, or the p.E326K risk polymorphism, tend to have a significantly earlier age at onset (AAO) of motor symptoms [2, 3], more rapid cognitive decline with a greater effect on working memory/executive function and visuospatial abilities[6, 7], and more pronounced postural instability and gait difficulty (PIGD) [6]. Thus, it is widely accepted that GBA pathogenic mutations and some polymorphisms (such as p.E326K) not only modify PD risk but also influence the heterogeneity in symptom progression of PD patients.

Most studies assessing GBA-related PD risk have been performed in European and Asian-derived populations, while very few studies have been done in other populations such as Latinos.

The aim of the present study was to characterize the frequency and distribution of GBA variants in a cohort of 602 PD patients and 319 healthy controls from Colombia and Peru, and to assess their role in modifying risk and AAO of PD patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

We screened a total of 602 unrelated PD patients and 319 healthy controls recruited in Medellin, Colombia and Lima, Peru (Table 1). All of the individuals from Peru were recruited through the standardized protocol of the Latin American Research Consortium on the Genetics of Parkinson’s disease (LARGE-PD) without consideration of AAO. In contrast, participants from Colombia were added post hoc to LARGE-PD from a previous study with an enrollment bias for early-onset PD (EOPD; defined as AAO < 50 yrs) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the study population and logistic regression results for association between GBA variants and risk for PD

| PD | CTRL | OR (95% CI) p |

PD | CTRL | OR (95% CI) p |

PD | CTRL | OR (95% CI) p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 131 | 164 | 471 | 155 | 602 | 319 | |||

| 63 (49.2) | 82 (50) | 258 (54.8) | 49 (31.8) | 321 (53.6) | 131 (41.2) | |||

| 64.6 ± 13.4 (28–92) | 53.8 ± 14.1 (20–82) | 62.1 ± 12.2 (18–90) | 54 ± 12.8 (24–85) | 62.6 ± 12.5 (18–92) | 53.9 ± 13.5 (20–85) | |||

| 49.3 ± 16.4 (9–82) | N/A | 57.1 ± 13.2 (10–80) | N/A | 55.4 ± 14.3 (9–82) | N/A | |||

| 46.9 | N/A | 24.2 | N/A | 29.2 | N/A | |||

| 13 (9.9) | 3 (1.8) | 5.9 (1.5–23.7) 0.012 |

20 (4.2) | 2 (1.3) | 4.1 (0.9–18.6) 0.063 |

33 (5.5) | 5 (1.6) | 4.3 (1.6–11.5) 0.004 |

| 15 (11.4) | 4 (2.4) | 6.2 (1.8–21.2) 0.003 |

23 (4.9) | 2 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.0–19.9) 0.048 |

38 (6.3) | 6 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.7–10.4) 0.002 |

| 7 (6.0) | 2 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.2–36.3) 0.032 |

0 | 0 | N/A | 7 (1.3) | 2 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.5–13.6) 0.276 |

| 50.2 ± 16.3 | N/A | - | 57.4 ± 11.7 | N/A | - | 55.9 ± 14.2 | N/A | - |

| 43.7 ± 17.1 | N/A | 0.08f | 49.5 ± 11.6 | N/A | 0.005f | 47.1 ± 14.2 | N/A | 0.0003f |

| 42.4 ± 16.2 | N/A | 0.04f | 50.4 ± 11.7 | N/A | 0.0078f | 47.2 ± 14.1 | N/A | 0.0002f |

AAE= age at enrollment; AAO= age at onset; CI = confidence interval; CTRL = controls; EOPD= Early-Onset PD (≤50 years old); N = sample size; N/A = not applicable; OR = odds ratio; PD = Parkinson’s disease; y = years;

AAO was missing for 2 Colombian cases and 5 Peruvian cases;

mutation previously reported in at least one patient with Gaucher’s disease;

other GBA mutation carriers and p.E326K carriers were excluded from this analysis;

AAO of non-GBA carriers (no mutations nor p.E326K);

AAO of GBA mutation carriers;

AAO of GBA variant carriers (mutations + p.E326K);

one-tailed p-value (t-test)

All patients were evaluated by a movement disorder specialist at each site and met UK PD Society Brain Bank criteria for PD [8]. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at each site and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their enrollment in the study.

Mutation Screening

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using standard techniques. We amplified the entire GBA gene in a single 7,050-base-pair fragment to avoid the amplification of the pseudogene (Supplementary Table 1) and identify potential GBA-GBAP1 recombinants. Thereafter all 11 exons and intron-exon boundaries were sequenced, as previously described (Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Table 1) [7]. The sequencing success rate was 99.0%. Variants were numbered according to standard nomenclature (http://www.hgvs.org/mutnomen/) based on RefSeq NM_001005741.2 and NP_001005741.1 accession numbers removing the first 39 amino acids (Supplementary Table 2). A mutation was considered “pathogenic” if it was previously reported in at least 1 patient with GD in homozygous or compound heterozygous state or if it was predicted to have an obvious deleterious functional effect (e.g., frameshift or nonsense mutations). Previously published variants, such as p.E326K, which are not known to cause GD, were classified as polymorphisms. Rare nonsynonymous substitutions that have not been reported in GD patients were classified as variants of unknown significance.

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis assuming an additive model adjusted by sex and age was used to test for association between PD and GBA pathogenic mutations alone or in combination with the p.E326K risk polymorphism. The t-test was used to examine the association between GBA pathogenic mutations and AAO of motor symptoms. Analyses were performed using Stata software (version 14.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

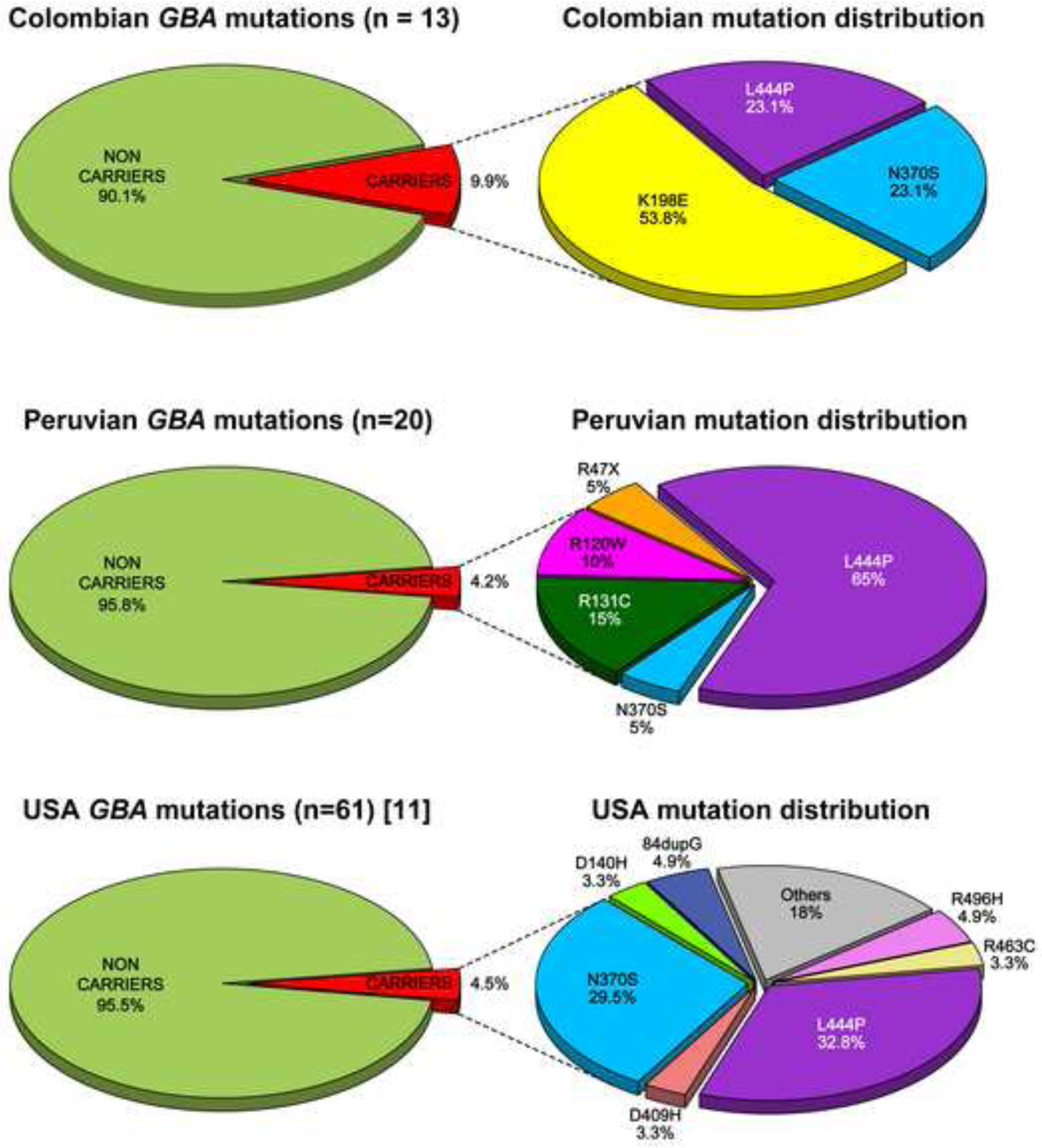

A total of 602 PD cases and 319 controls were included in this study (Table 1; combined cohort). Age at enrollment was comparable between cohorts for both patients and controls individually. The AAO was considerably earlier (~8 years) in the Colombian PD patients compared to the Peruvians, due to recruitment selection (see participants section). We identified a total of 10 different pathogenic mutations, 8 variants of unknown significance, and 3 nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Supplementary Table 2). Thirty-eight participants carried pathogenic mutations; 35 of these individuals were single heterozygotes and three were compound heterozygotes (Supplementary Table 3). Of the compound heterozygotes, two were PD patients who carried a pathogenic mutation (p.L444P) and the p.E326K SNP, and one was a control who carried a pathogenic mutation (p.K198E, rs773409311) and a variant of unknown significance (p.E388K, rs149171124) (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, the frequency of GBA pathogenic mutations was significantly different between PD patients (33/602; 5.5%) and healthy controls (5/319; 1.6%) in the combined sample; OR = 4.3 (1.6–11.5); p = 0.004; Table 1). The frequency of GBA pathogenic mutation carriers in the Colombian PD cohort (13/131; 9.9%) was more than double that observed among Peruvian PD patients (20/471; 4.2%). The higher overall frequency in the Colombian sample was driven by the presence of p.K198E, which was seen in more than half of the cases (7 of 13) and two controls, but was absent in the Peruvian cohort. It is noteworthy that while some common mutations in European derived populations (e.g. p.L444P, p.N370S) were found in both Colombian and Peruvian samples, their frequency varied between the two populations (Supplementary Table 2). p.L444P was the most common pathogenic variant (44.7%) in the combined cohort, and it was especially frequent in Peru (65%; Figure 1). The frequency of GBA pathogenic mutations in healthy controls was similar in the Colombian (3/164; 1.8%) and Peruvian (2/155; 1.3%) cohorts (Table 1). In addition to known pathogenic mutations, we also identified 3 nonsynonymous SNPs: p.K(−27)R, p.E326K and p.T369M. Since p.E326K has been shown to significantly increase PD risk [4], we repeated the analysis including individuals with this SNP. When included, the association between GBA variants and the risk of developing PD did not vary significantly (Table 1). In the combined sample, the mean AAO of motor impairment was significantly earlier in GBA pathogenic mutation carriers (~8 years) compared to non-carriers (p = 0.0003). The results did not change significantly when including p.E326K carriers (Table 1).

Figure 1. Pathogenic GBA mutation distribution in three different populations.

Frequency and distribution of GBA mutation carriers in PD patients from Colombia (A), Peru (B) and a US population [7] (C).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sequenced the entire GBA coding region in a large cohort of PD patients and healthy controls from two Latin American countries, Colombia and Peru. Our results show that GBA carriers from Colombia and Peru have a 6 and 4-fold increased risk for PD respectively, comparable to previous studies of European-derived populations [2]. However, the distribution and frequency of the variants identified differed, both between the Colombian and Peruvian samples, and between these two cohorts and a non-Hispanic white cohort from the US (Figure 1) [7].

In our Colombian cohort, the frequency of PD cases with GBA pathogenic mutations (9.9%) was higher than in our Peruvian cohort (4.2%) and in previous studies of populations of European descent (4–5%) [2, 7], but lower than the frequencies reported in Ashkenazi PD patients (~20%) [2]. The high frequency in the Colombian sample could be due to enrollment bias since any PD cohort with an earlier AAO is more likely to have a larger proportion of GBA carriers. However, in our cohort we believe that the higher carrier prevalence is primarily due to the presence of p.K198E, since the combined frequency of all other mutations was very similar in Colombia (6/131; 4.5%) and Peru (20/471; 4.2%). In fact. p.K198E alone accounted for more than half of the GBA-related PD cases (54%). The remaining 46% of the carriers had either p.L444P or p.N370S (Figure 1). Among GBA carriers in the Peruvian cohort, p.L444P was the predominant pathogenic mutation (65%), p.N370S was rare (5%), perhaps due to the difference in European ancestry between both populations. Three other pathogenic mutations (p.R47X (rs-ID not available), p.R120W (rs439898), p.R131C, (rs398123530) accounted for the remaining carriers (30%). The overall frequency in our Colombian sample was similar to the one reported in a Japanese PD cohort (9.4%) [9]. However, the distribution of pathogenic mutations was quite different; in the Japanese study two pathogenic mutations (p.R120W and RecNcil) accounted for more than 55% of all GBA-related PD cases. Thus, our results further demonstrate that the spectrum and frequency of pathogenic mutations in GBA-related PD can vary substantially between populations.

Our study is the first to report that the pathogenic mutation p.K198E, present in over 5% of our Colombian patients, increases PD risk (OR = 6.5, CI = 1.2–36.3; p = 0.032, Table 1). This variant was first identified in the homozygous state in an infant of Colombian descent with severe type 2 GD who died at the age of 2.5 years [10]. A study analyzing 25 Colombian GD patients reported three of them to be compound heterozygous carriers of p.K198E and p.N370S [11]. None of them presented with neurological abnormalities. Interestingly, all mutation carriers were found in the same region of Northwest Colombia (Antioquia) where Medellin is located and where our study participants were ascertained. Inhabitants of Antioquia, and more specifically the “paisa” population, constitute a genetically isolated community, suggesting a possible founder effect which could explain the high frequency observed for p.K198E in this population. A similar phenomenon has been previously described for a pathogenic mutation (p.C212Y) in the PRKN gene [12].

Only three other studies have assessed the frequency of GBA pathogenic mutations in Latin American PD patients to date. Furthermore, in all of these studies participants were only screened for the two most common pathogenic mutations, p.N370S and p.L444P. In 2010, an association study of 110 Brazilian PD patients and 155 Brazilian healthy controls reported an over-representation of GBA pathogenic mutations in the PD group compared with controls (5.4% vs 0%, p = 0.0047) [13]. This study identified two PD carriers for each mutation, p.N370S and p.L444P, respectively. A second Brazilian study from 2013 analyzed 141 Brazilian PD patients (no healthy controls) and found three p.L444P carriers (2.1%) and one p.N370S carrier (0.7%) [14]. Finally, a study performed in 128 Mexican Mestizo (MM) early onset PD patients (AAO<45 years old) and 252 healthy MM controls reported an excess of p.L444P in the PD group (n=7, 5.5%) compared to controls (n=0, p = 0.014) [15], and p.N370S was entirely absent in all participants. Overall, these data suggest that the frequency of p.N370S among PD patients is low in populations with high Amerindian ancestry, such as MM or Peruvians.

We also identified three nonsynonymous SNPs in our sample including p.E326K, a common PD risk variant that occurs at a frequency of 3.5–7% in European-derived populations [5, 7]. p.E326K was rare in our PD cohorts from Colombia and Peru (1.5% and 0.6% respectively) suggesting that this variant has a lesser role in determining risk in these populations.

The biological mechanism by which GBA pathogenic mutations increase PD risk is still unclear. Interestingly, in populations of European origin severe pathogenic mutations have a substantially higher effect on PD risk than mild mutations [16]. Furthermore, there is some evidence of heterogeneity in the effects of different GBA variants on motor and cognitive phenotypes in PD [7]. Whether similar genotype-phenotype correlations will hold true in Latin America remains to be determined. This issue might prove to be particularly complex if the distribution of variants among local subpopulations varies substantially, as we observed in our Peruvian and Colombian samples. Complete screening of the GBA gene combined with detailed longitudinal motor and cognitive assessments of large Latin American PD cohorts will be necessary to address this question [7].

Our study supports the hypothesis that GBA pathogenic mutations increase PD risk in Colombians and Peruvians, and suggests that novel population specific mutations might await discovery in other Latin American populations. It also highlights the importance of performing additional studies in Latin American populations to better phenotypically characterize GBA carriers and assess whether or not they have a poorer prognosis in terms of motor and cognitive performance. Furthermore, the high frequency of GBA carriers among Colombian PD patients makes this population especially attractive to study novel therapeutic approaches that target GBA-related PD.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

GBA mutations confer a 4 and 6 fold increase in PD risk in Peru and Colombia

GBA mutations are also associated with earlier age at onset (~8 yrs)

We identified a novel population specific mutation in Colombia (p.K198E)

The frequency of mutations in Colombian patients doubled most populations (9.9%)

Colombian PD patients may be a great target to apply novel GBA-related therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by “The Committee for Development and Research” (Comite para el desarrollo y la investigación-CODI)-Universidad de Antioquia (UdeA) grant #2017-14466 to MJ-Del-Rio and CV-P, The Parkinson’s Foundation, the American Parkinson’s Disease Association and the NIH (R01 NS065070).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- [1].Deng H, Wang P, Jankovic J, The genetics of Parkinson disease, Ageing research reviews 42 (2018) 72–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, Bar-Shira A, Berg D, Bras J, Brice A, Chen CM, Clark LN, Condroyer C, De Marco EV, Durr A, Eblan MJ, Fahn S, Farrer MJ, Fung HC, Gan-Or Z, Gasser T, Gershoni-Baruch R, Giladi N, Griffith A, Gurevich T, Januario C, Kropp P, Lang AE, Lee-Chen GJ, Lesage S, Marder K, Mata IF, Mirelman A, Mitsui J, Mizuta I, Nicoletti G, Oliveira C, Ottman R, Orr-Urtreger A, Pereira LV, Quattrone A, Rogaeva E, Rolfs A, Rosenbaum H, Rozenberg R, Samii A, Samaddar T, Schulte C, Sharma M, Singleton A, Spitz M, Tan EK, Tayebi N, Toda T, Troiano AR, Tsuji S, Wittstock M, Wolfsberg TG, Wu YR, Zabetian CP, Zhao Y, Ziegler SG, Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease, N. Engl. J. Med 361(17) (2009) 1651–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Clark LN, Ross BM, Wang Y, Mejia-Santana H, Harris J, Louis ED, Cote LJ, Andrews H, Fahn S, Waters C, Ford B, Frucht S, Ottman R, Marder K, Mutations in the glucocerebrosidase gene are associated with early-onset Parkinson disease, Neurology 69(12) (2007) 1270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chang D, Nalls MA, Hallgrimsdottir IB, Hunkapiller J, van der Brug M, Cai F, Kerchner GA, Ayalon G, Bingol B, Sheng M, Hinds D, Behrens TW, Singleton AB, Bhangale TR, Graham RR, A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci, Nat. Genet 49(10) (2017) 1511–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Duran R, Mencacci NE, Angeli AV, Shoai M, Deas E, Houlden H, Mehta A, Hughes D, Cox TM, Deegan P, Schapira AH, Lees AJ, Limousin P, Jarman PR, Bhatia KP, Wood NW, Hardy J, Foltynie T, The glucocerobrosidase E326K variant predisposes to Parkinson’s disease, but does not cause Gaucher’s disease, Mov. Disord 28(2) (2013) 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davis MY, Johnson CO, Leverenz JB, Weintraub D, Trojanowski JQ, Chen-Plotkin A, Van Deerlin VM, Quinn JF, Chung KA, Peterson-Hiller AL, Rosenthal LS, Dawson TM, Albert MS, Goldman JG, Stebbins GT, Bernard B, Wszolek ZK, Ross OA, Dickson DW, Eidelberg D, Mattis PJ, Niethammer M, Yearout D, Hu SC, Cholerton BA, Smith M, Mata IF, Montine TJ, Edwards KL, Zabetian CP, Association of GBA Mutations and the E326K Polymorphism With Motor and Cognitive Progression in Parkinson Disease, JAMA Neurol 73(10) (2016) 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mata IF, Leverenz JB, Weintraub D, Trojanowski JQ, Chen-Plotkin A, Van Deerlin VM, Ritz B, Rausch R, Factor SA, Wood-Siverio C, Quinn JF, Chung KA, Peterson-Hiller AL, Goldman JG, Stebbins GT, Bernard B, Espay AJ, Revilla FJ, Devoto J, Rosenthal LS, Dawson TM, Albert MS, Tsuang D, Huston H, Yearout D, Hu SC, Cholerton BA, Montine TJ, Edwards KL, Zabetian CP, GBA Variants are associated with a distinct pattern of cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord 31(1) (2016) 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ, Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases, J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 55(3) (1992) 181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mitsui J, Mizuta I, Toyoda A, Ashida R, Takahashi Y, Goto J, Fukuda Y, Date H, Iwata A, Yamamoto M, Hattori N, Murata M, Toda T, Tsuji S, Mutations for Gaucher disease confer high susceptibility to Parkinson disease, Arch. Neurol 66(5) (2009) 571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Orvisky E, Park JK, Parker A, Walker JM, Martin BM, Stubblefield BK, Uyama E, Tayebi N, Sidransky E, The identification of eight novel glucocerebrosidase (GBA) mutations in patients with Gaucher disease, Hum. Mutat 19(4) (2002) 458–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pomponio RJ, Cabrera-Salazar MA, Echeverri OY, Miller G, Barrera LA, Gaucher disease in Colombia: mutation identification and comparison to other Hispanic populations, Mol. Genet. Metab 86(4) (2005) 466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pineda-Trujillo N, Apergi M, Moreno S, Arias W, Lesage S, Franco A, Sepulveda-Falla D, Cano D, Buritica O, Pineda D, Uribe CS, de Yebenes JG, Lees AJ, Brice A, Bedoya G, Lopera F, Ruiz-Linares A, A genetic cluster of early onset Parkinson’s disease in a Colombian population, Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 141B(8) (2006) 885–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dos Santos AV, Pestana CP, Diniz KR, Campos M, Abdalla-Carvalho CB, de Rosso AL, Pereira JS, Nicaretta DH, de Carvalho WL, Dos Santos JM, Santos-Reboucas CB, Pimentel MM, Mutational analysis of GIGYF2, ATP13A2 and GBA genes in Brazilian patients with early-onset Parkinson’s disease, Neurosci. Lett 485(2) (2010) 121–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Abreu GM, Valenca DC, Campos MJ, da Silva CP, Pereira JS, Araujo Leite MA, Rosso AL, Nicaretta DH, Vasconcellos LF, da Silva DJ, Della Coletta MV, Dos Santos JM, Goncalves AP, Santos-Reboucas CB, Pimentel MM, Autosomal dominant Parkinson’s disease: Incidence of mutations in LRRK2, SNCA, VPS35 and GBA genes in Brazil, Neurosci. Lett 635 (2016) 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gonzalez-Del Rincon Mde L, Monroy Jaramillo N, Suarez Martinez AI, Yescas Gomez P, Boll Woehrlen MC, Lopez Lopez M, Alonso Vilatela ME, The L444P GBA mutation is associated with early-onset Parkinson’s disease in Mexican Mestizos, Clin. Genet 84(4) (2013) 386–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gan-Or Z, Amshalom I, Kilarski LL, Bar-Shira A, Gana-Weisz M, Mirelman A, Marder K, Bressman S, Giladi N, Orr-Urtreger A, Differential effects of severe vs mild GBA mutations on Parkinson disease, Neurology 84(9) (2015) 880–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.