Abstract

Background

Fatigue is a common and potentially distressing symptom for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with no accepted evidence‐based management guidelines. Evidence suggests that biologic interventions improve symptoms and signs in RA as well as reducing joint damage.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of biologic interventions on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases up to 1 April 2014: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Current Controlled Trials Register, the National Research Register Archive, The UKCRN Portfolio Database, AMED, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Social Science Citation Index, Web of Science, and Dissertation Abstracts International. In addition, we checked the reference lists of articles identified for inclusion for additional studies and contacted key authors.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials if they evaluated a biologic intervention in people with rheumatoid arthritis and had self reported fatigue as an outcome measure.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers selected relevant trials, assessed methodological quality and extracted data. Where appropriate, we pooled data in meta‐analyses using a random‐effects model.

Main results

We identified 32 studies for inclusion in this current review. Twenty studies evaluated five anti‐tumour necrosis factor (anti‐TNF) biologic agents (adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab and infliximab), and 12 studies focused on five non‐anti‐TNF biologic agents (abatacept, canakinumab, rituximab, tocilizumab and an anti‐interferon gamma monoclonal antibody). All but two of the studies were double‐blind randomised placebo‐controlled trials. In some trials, patients could receive concomitant disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These studies added either biologics or placebo to DMARDs. Investigators did not change the dose of the latter from baseline. In total, these studies included 9946 participants in the intervention groups and 4682 participants in the control groups. Overall, quality of randomised controlled trials was moderate with a low to unclear risk of bias in the reporting of the outcome of fatigue. We downgraded the quality of the studies from high to moderate because of potential reporting bias (studies included post hoc analyses favouring reporting of positive result and did not always include all randomised individuals). Some studies recruited only participants with early disease. The studies used five different instruments to assess fatigue in these studies: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Domain (FACIT‐F), Short Form‐36 Vitality Domain (SF‐36 VT), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (0 to 100 or 0 to 10) and the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS). We calculated standard mean differences for pooled data in meta‐analyses. Overall treatment by biologic agents led to statistically significant reduction in fatigue with a standardised mean difference of −0.43 (95% confidence interval (CI) −0.38 to −0.49). This equates to a difference of 6.45 units (95% CI 5.7 to 7.35) of FACIT‐F score (range 0 to 52). Both types of biologic agents achieved a similar level of improvement: for anti‐TNF agents, this stood at −0.42 (95% CI −0.35 to −0.49), equivalent to 6.3 units (95% CI 5.3 to 7.4) on the FACIT‐F score; and for non‐anti‐TNF agents, it was −0.46 (95% CI −0.39 to −0.53), equivalent to 6.9 units (95% CI 5.85 to 7.95) on the FACIT‐F score. In most studies, the double‐blind period was 24 weeks or less. No study assessed long‐term changes in fatigue.

Authors' conclusions

Treatment with biologic interventions in patients with active RA can lead to a small to moderate improvement in fatigue. The magnitude of improvement is similar for anti‐TNF and non‐anti‐TNF biologics. However, it is unclear whether the improvement results from a direct action of the biologics on fatigue or indirectly through reduction in inflammation, disease activity or some other mechanism.

Keywords: Humans; Abatacept; Abatacept/therapeutic use; Adalimumab; Adalimumab/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal; Antibodies, Monoclonal/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized/therapeutic use; Antirheumatic Agents; Antirheumatic Agents/therapeutic use; Arthritis, Rheumatoid; Arthritis, Rheumatoid/complications; Arthritis, Rheumatoid/drug therapy; Certolizumab Pegol; Certolizumab Pegol/therapeutic use; Etanercept; Etanercept/therapeutic use; Fatigue; Fatigue/drug therapy; Fatigue/etiology; Fatigue/therapy; Immunosuppressive Agents; Immunosuppressive Agents/therapeutic use; Infliximab; Infliximab/therapeutic use; Interferon‐gamma; Interferon‐gamma/antagonists & inhibitors; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Rituximab; Rituximab/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Biological interventions for the management of fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis

Background

What is rheumatoid arthritis and what are biologics?

When you have rheumatoid arthritis, your immune system, which normally fights infection, attacks the lining of your joints, causing swelling, stiffness and pain. The small joints of your hands and feet are usually affected first. There is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis at present, so treatments aim to relieve pain and stiffness and improve your ability to move. Biologics are medications that can reduce joint inflammation, improve symptoms and prevent joint damage.

Fatigue is an important symptom in people with rheumatoid arthritis. However, there is no consensus on the most effective management approaches for it. A number of studies have explored the effects of biologic response modifiers (biologics) in the management of rheumatoid arthritis and associated symptoms such as fatigue. We carried out the current review to evaluate the effects of these therapies on fatigue in adults with rheumatoid arthritis.

Study characteristics

We searched for all research published up to 1 April 2014, finding 32 relevant studies. There were 19 studies on five anti‐TNF biologics (adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab and infliximab) and 12 studies on five non‐anti‐TNF biologics (abatacept, canakinumab, rituximab, tocilizumab and an anti‐interferon gamma monoclonal antibody).

Key results

Altogether 9,946 participants received biologics and 4,682 participants received standard therapy. All but two of the studies were randomised placebo‐controlled trials, the gold standard in terms of study quality. We compared the effects of biologics versus placebo. In some studies, participants may have been taking standard therapy for rheumatoid arthritis at the start of the trial. In these studies, investigators added either biologics or placebo treatment to standard therapy. Overall, treatment by biologics led to small to moderate reductions (9 units reduction on a 0‐52 scale) in patient‐reported fatigue compared with 3 units in participants treated by placebo. It is unclear whether this improvement is due to a reduction in overall disease activity, a direct effect of the biologics or some other mechanism.

Quality of the evidence

There may have been some potential bias in the way investigators analysed data, and some studies did not include all randomised individuals, so we judged the quality of the evidence to be only moderate rather than high.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. All biologics for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis.

| All biologics for fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis | |||||

|

Patient or population: patients with fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis

Settings: hospital, outpatient clinics

Intervention: all biologics Comparison: placebo or usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Control | Biologics | ||||

| Fatigue continuous measures Follow‐up: median 24 weeks | The mean change in fatigue score from baseline in the control for all biologics ‐ was 3.3 units lower of the FACIT‐F score or 3.9 lower of the SF‐36 vitality. | The standardised mean difference between control and intervention groups at study endpoint for all biologics was 6.45 units lower of the FACIT‐F score or 7.65 units of SF‐36 vitality | 14,628 (30 studies) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ Moderatea | SMD −0.43 (95% CI −0.49 to −0.38). An SMD of 0.43 would be considered as a moderate effect. This equates to a difference of 6.45 units (95% CI 5.70 to 7.35) of FACIT‐F score (range 0‐52) or 7.65 units (95% CI 6.76 to 8.72) of SF‐36 vitality (range 0‐100). NNTB 5 (95% CI 5 to 6) |

| The mean change in fatigue score from baseline in the control for anti‐TNF biologics ‐ was 3.3 units lower of FACIT‐F score or 3.9 lower of the SF‐36 vitality. | The standardised mean difference between control and intervention groups at study endpoint for anti‐TNF biologics was 6.3 units lower of the FACIT‐F score or 7.5 units of SF‐36 vitality. | 8946 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Moderatea | SMD −0.42 (95% CI−0.35 to −0.49). An SMD of 0.42 would be considered as a moderate effect. This equates to a difference of 6.3 units (95% CI: 5.3 to 7.4) of FACIT‐F score (range 0‐52) or 7.5 units (95% CI 6.2 to 8.7) of SF‐36 vitality (range 0‐100). NNTB 6 (95% CI 5 to 7) | |

| The mean change in fatigue score from baseline in the control for non‐anti‐TNF biologics ‐ was 0.5 units lower of FACIT‐F score or 0.59 lower of the SF‐36 vitality. | The standardised mean difference between control and intervention groups at study endpoint for non‐anti‐TNF biologics was 6.9 units lower of FACIT‐F score or 8.19 units of SF‐36 vitality. | 5682 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Moderatea | An SMD of 0.46 would be considered as a moderate effect. This equates to a difference of 6.9 units (95% CI 5.85 to 7.95) of FACIT‐F score (range 0‐52) or 8.19 units (95% CI 6.94 to 9.43) of SF‐36 vitality (range 0‐100). NNTB 5 (95% CI 4 to 6) | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; NNTB: number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome; SMD: standardised mean difference. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aThe quality of the studies were downgraded from high to moderate because of potential reporting bias (studies included post hoc analysis favouring reporting of positive result and studies did not always include all randomised individuals.

Background

Description of the condition

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune, systemic, inflammatory condition causing pain and synovitis in the joints of the hands and feet (Conaghan 1999). Repeated flares of disease activity cause symptoms of pain, fatigue, stiffness and loss of function. People with RA have identified fatigue as a key problem, which they consider harder to manage than pain (Hewlett 2005). Quantitative studies consistently show that significant fatigue occurs in up to 70% of patients in the UK (almost 0.4 million people) and is as common and severe as pain (Department of Health 2006; Wolfe 1996). There is a Cochrane review on the effect of non‐pharmaceutical interventions on fatigue in patients with RA (Cramp 2013).

Description of the intervention

Medication for controlling the inflammatory response (and therefore symptoms) in RA comprises non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), rapid introduction of disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticoids and biologic therapies to inhibit disease progression (Luqmani 2006). Although there is evidence that biologic interventions can improve symptoms of pain, stiffness, inflammation and loss of function (Blumenauer 2002; Blumenauer 2003; Maxwell 2009; Mertens 2009; Navarro‐Sarabia 2005; Singh 2009), and studies increasingly include fatigue as a secondary outcome, no systematic review has clearly established the evidence for improvement in RA fatigue. Other pharmacological interventions such as anti‐depressants are often also used to improve intractable symptoms of RA such as pain and may also improve fatigue. A separate review is analysing these agents, along with DMARDs and NSAIDs.

How the intervention might work

RA fatigue probably acts through multiple and complex pathways that vary between and within patients over time (Hewlett 2008). Inflammatory activity may directly cause fatigue through systemic effects or indirectly through its effects on pain and function (Pollard 2006). Therefore, biologic agents may improve RA fatigue by reducing the inflammatory components of fatigue, pain and function.

Why it is important to do this review

People with RA have clearly identified fatigue as a common, unmanageable symptom that reduces quality of life (Hewlett 2005), and there is international consensus that all clinical trials should measure it (Kirwan 2007). In addition, ongoing research identifies fatigue as a key symptom associated with disease flare. Although there is no systematic review on the evidence for the effect of pharmacological interventions on RA fatigue, investigators often report the symptom as a secondary outcome. Clinicians need to be able to evaluate the potential (or limitations) of such interventions for reducing RA fatigue in order to reach concordant decisions with patients on treatment options.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of biologic interventions on fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Inclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trials of biologics in adults with confirmed RA that included fatigue as a primary or secondary outcome measure (and not just an adverse effect) and reported it separately for RA participants (Arnett 1988).

Exclusion criteria

Studies that only investigated non‐biologic interventions or non‐pharmacological interventions.

Types of participants

Adults (usually over 18 years of age) with a diagnosis of RA either confirmed by rheumatologist or using American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria (Arnett 1988).

Types of interventions

All recognised biologic interventions. These included anti‐TNF (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol and golimumab) and non‐anti‐TNF (rituximab, abatacept, tocilizumab, anakinra, canakinumab and anti‐IFN gamma monoclonal antibody) biologic agents.

The comparison arm could have been a placebo, alternative intervention (pharmacological or non‐pharmacological) or usual care, including no specific intervention for fatigue.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes for this systematic review were change in self reported fatigue scores using validated measures and adverse events. We defined validated measures as instruments used to assess fatigue in clinical trials or observational studies as detailed in a recent review (Hewlett 2007). We included adverse events in the initial protocol; however, since then a separate Cochrane review has assessed adverse events associated with anti‐TNF and non‐anti‐TNF biologic treatments, so we have referred to this publication rather than conducting a separate analysis (Singh 2011).

Secondary outcomes

In addition to presenting data on the primary outcome of fatigue in the 'Summary of findings' table, we also extracted the secondary outcomes of pain, anxiety and depression.

Search methods for identification of studies

We developed our search strategies in line with recommendations from the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Review Group and present them in Appendix 1. We applied these search strategies to all databases, adapting them appropriately to suit database style.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014, Issue no).

MEDLINE (1966 to April 2014).

EMBASE (1983 to April 2014).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2007 to April 2014).

Current Controlled Trials Register (USA) (2000 to April 2014).

The National Research Register (NRR) Archive (UK) (2006 to April 2014).

The UKCRN Portfolio Database (UK) (2006 to April 2014).

AMED (1985 to April 2014).

CINAHL (1982 to April 2014).

PsycINFO (1974 to April 2014).

Social Science Citation Index (1990 to April 2014).

Web of Science (1990 to April 2014).

Dissertation Abstracts International (1871 to April 2014).

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (Nov 2005 to April 2014).

Searching other resources

In addition, we handsearched the reference lists of included studies and previous review papers to find additional studies, as well as the Topical Review Series on fatigue in musculoskeletal disease (Hewlett 2008). We contacted relevant authors in the field to ask about unpublished research that the search strategies could not have detected.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors assessed titles and abstracts for all records identified through the search strategies, retrieving full texts for all those that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We also acquired the full reports if there was any uncertainty or disagreement surrounding their inclusion, or if abstracts were not available and it was not possible to exclude the trial on title alone. Two independent review authors screened all full‐text articles for inclusion/exclusion criteria, resolving disagreements by discussion and the involvement of an arbiter where necessary.

Data extraction and management

For data extraction, the review team allocated papers to different authors according to their areas of expertise, and two reviewers independently retrieved the following details for each publication, tabulating them on a standardised form: intervention (including characteristics and duration); details of the participants' health status; assignment to groups (including process used, concealment and comparability of groups); outcome measures; details of outcome measures used for assessing fatigue, timing of measurements; adherence to intervention/control, sample size and statistical analysis methods (including use of intention‐to‐treat principle) as well as power to detect a change in fatigue, adverse events and withdrawals.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The two review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of each trial using individual components of quality from tools such as the one provided by Cochrane. Additionally, two independent review authors assessed the risk of bias of the included studies. As recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008), we assessed the following methodological domains.

Sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other potential threats to validity (e.g. appropriate use of co‐interventions).

We explicitly assessed each of these domains as being at 'low' or 'high' risk of bias; where insufficient information was available, or there was uncertainty over the potential for bias, we rated the study as being at 'unclear' risk of bias in that domain.

We also assessed the power of the study to detect change in RA fatigue by examining the power calculations reported in the studies. Where this was missing, we based our assessment on recent publications focusing on the Patient Acceptable Symptom State or the minimally important differences in RA fatigue (Heiberg 2008; Wells 2007). We also used methods described in (Hewlett 2007) to assess the validity of the fatigue measure.

Measures of treatment effect

As we expected, the identified studies used a range of fatigue outcome measures, so we calculated standardised mean differences (SMD). We recorded the central estimate (mean) and standard deviation (SD). Where the standard deviations were not explicitly stated, we calculated them from the standard error, the different means and their respective confidence intervals (CIs) or P values. Where studies described adverse events as dichotomous data, we had planned to report them as the proportion of participants experiencing the event in each arm and would have made comparisons using the risk ratio (RR) and the corresponding 95% CI. For rare events (< 10%), we planned to report the Peto odds ratio. However, as stated in Primary outcomes, in the end we did not perform any analyses on adverse events since this has already been studied in a separate Cochrane review (Singh 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

Some studies included multiple doses of the same intervention. In these cases, we divided the control group into equal numbers and included pairwise comparisons in the meta‐analysis as recommended in sections 9.3.9 and 16.5.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Dealing with missing data

Where the change in scores was not available, we sought these data from the authors. Failing that, we imputed them using methods recommended in section 16.1.3.2 of Higgins 2008.

We carried out an intention‐to‐treat analysis in studies that included participants allocated to the intervention arm regardless of whether or not they completed the follow‐up. In these studies we assumed that participants who dropped out of the study had no changes in their outcomes, assigning a conservative assessment of response to treatment. We requested further details from authors in cases where published data were incomplete.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Where appropriate, we formally assessed heterogeneity of the data using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We judged a value greater than 50% to represent substantial heterogeneity. Where we detected this level of heterogeneity and there were sufficient studies available, we conducted subgroup analyses in an attempt to explain the heterogeneity.

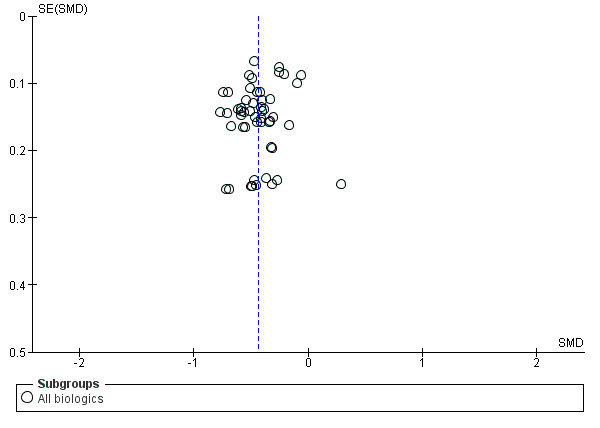

Assessment of reporting biases

We used a funnel plot to assess the possibility of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We evaluated the quality of included studies using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2008), which employs the following rating system: randomised trials (high), downgraded randomised trials (moderate), double‐downgraded randomised trials (low) and triple‐downgraded randomised trials (very low). The quality ratings may be decreased by:

limitations in the design and implementation of available studies, suggesting a high likelihood of bias;

indirectness of evidence (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes);

unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency of results (including problems with subgroup analyses);

imprecision of results (wide confidence intervals); or

high probability of publication bias.

We expected a mixture of changes from baseline and absolute group differences across a variety of measures of RA fatigue. We also anticipated some variation in methods of analysis, including absolute difference compared between groups, and baseline‐adjusted differences between groups. We followed the Cochrane guidelines described in section 9.4.5.2 of Higgins 2008 to decide which group of studies we could include in any meta‐analysis. We imputed the SD if necessary as described in section 16.1.3.

Summary of finding tables

We present the grading and meta‐analyses in a 'Summary of findings' table.

Where there was no heterogeneity, we used a fixed‐effect model, and where there was heterogeneity, we used a random‐effects model. When the outcome used, or the number, quality or heterogeneity of existing trials contraindicated meta‐analysis, we reported and discussed each study individually, using effect sizes for fatigue difference (differences divided by the SD) and Cohen's statistic (0.2 to 0.5 = small effect, 0.5 to 0.8 = moderate, > 0.8 = large effect) (Cohen 1998). We calculated SMDs for pooled data in meta‐analysis. If trials reported more than one outcome measure, such as FACIT and SF‐36 VT, we used the latter. Negative values indicated reduction in the fatigue.

In order to estimate the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) from the SMD, we performed a log transformation of the SMD to an odds ratio (OR) (Chinn 2000). Subsequently, we combined the resulting OR with an assumed control event rate (CER = 0.5) generating an estimated NNTB. These control group risks refer to proportions of people who improved by some (unspecified) amount in the continuous outcome ('responders').

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where sufficient studies were available and the data were heterogenous, we carried out separate meta‐analyses for studies according to different biologic agents.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned the following sensitivity analyses a priori in order to explore differences in effect size and to assess whether the conclusions were robust to the decision‐making process.

The effect of risk of bias in included studies ‐ defined as adequate allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessors.

The effect of imputing missing data or transforming variables.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

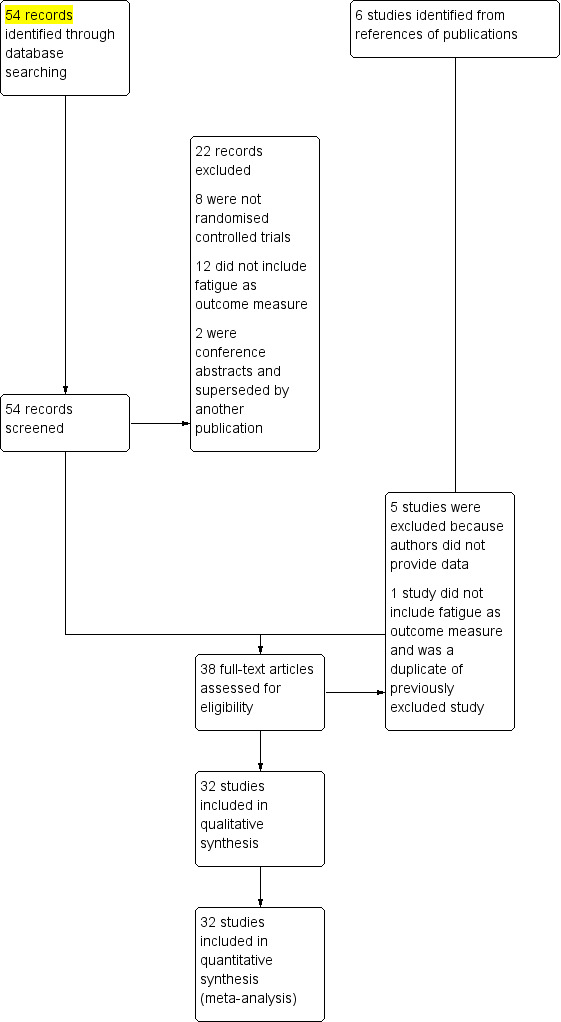

We undertook a comprehensive literature search, including screening of titles and abstracts (where available). We retrieved 54 full‐text references for further evaluation, including 32 that met the criteria for the current review and excluding the remaining 22. Handsearching of reference lists led to the retrieval of six further full‐text studies; we excluded one because fatigue was not an outcome measure and five because we were unable to obtain necessary data from the authors (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

All the studies recruited participants with established RA who fulfilled ACR criteria (Arnett 1988). There were 20 studies of five anti‐TNF agents: one studied infliximab (Maini 1999), three studied etanercept (Bae 2013; Emery 2008; Moreland 1999), six studied adalimumab (Hørslev‐Petersen 2014; Keystone 2004; Mittendorf 2007; Soubrier 2009; Strand 2012b; Weinblatt 2003), five studied certolizumab pegol (Choy 2012; Fleischmann 2009; Pope 2012; Smolen 2009a; Strand 2009), and five studied golimumab (Emery 2009; Keystone 2009; Li 2013; Smolen 2009b; Weinblatt 2013). All but two were randomised placebo‐controlled trials: Mittendorf 2007 reported the result of a pooled analysis of six randomised placebo‐controlled trials of adalimumab in RA, while Bae 2013 was a randomised open‐label active comparator trial of etanercept. Of the 12 non‐anti‐TNF biologic studies, 4 studied abatacept (Genovese 2005; Kremer 2003; Kremer 2006; Schiff 2008), three studied rituximab (Cohen 2006; Emery 2006; Rigby 2011), three studied tocilizumab (Genovese 2008; Smolen 2008; Strand 2012a), one studied canakinumab (Alten 2011), and one was an early phase trial of an anti‐IFN gamma monoclonal antibody (Lukina 1998). All but two of these studies were randomised placebo‐controlled trials: Bae 2013 compared etanercept with standard DMARD, and Lukina 1998 (which was translated from Russian) compared the effect of anti‐interferon gamma (anti‐IFNγ) monoclonal antibody with anti‐TNF antibodies as well as a combination of anti‐IFNγ and anti‐TNF antibodies. The sample size of Lukina 1998 was not based on statistical estimation; the study only recruited 25 participants and allocated just five to each treatment arm. This study (Lukina 1998) and the study by Maini 1999 did not contribute data to the meta‐analysis as we were unable to obtain precise estimate including standard deviation of change from the authors. In some trials, both active participants and controls could receive concomitant DMARDs. These studies added either biologics or placebo to DMARDs. The dose of the latter did not change from baseline. In total, these studies included 9,946 participants in the intervention groups and 4,682 participants in the control groups.

The primary outcomes of the included studies were disease activity, mostly assessed by ACR response criteria. The only exception is the pooled analyses in Mittendorf 2007, which focused on patient‐reported outcomes. None of the studies used fatigue as their primary outcome. These studies used five different instruments to assess fatigue: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Domain (FACIT‐F), Short Form‐36 Vitality Domain (SF‐36 VT), visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 to 100 or 0 to 10) and the Numerical Rating Scale NRS (0 to 10). The most commonly used instrument was SF‐36 VT, which authors reported in 15 studies. Nine studies used the FACIT‐F, five used a VAS, and three used an NRS. Fatigue measures were taken at the primary endpoints, which for most trials were at 24 weeks or less. One trial assessed fatigue at six weeks (Pope 2012), two trials at three months (Genovese 2005; Kremer 2003), and two studies at week 52 (Keystone 2004; Kremer 2006). Most papers did not provide data on pain, anxiety or depression, hence we were unable to conduct analyses of these secondary outcomes.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐two excluded publications did not meet the review inclusion criteria for the following reasons: 8 were not randomised controlled trials (Cella 2005; Duggan 2009; Frampton 2007; Kavanaugh 2012; Sansonno 2003; Strand 2012; Strand 2014; Yount 2007), 12 did not report fatigue as an outcome measure (Breedveld 2005; Furst 2003; Genovese 2010; Grigor 2004; Haugeberg 2009; Moreland 2000; Moreland 2002; Kavanaugh 2003; Kim 2007; Kremer 2008; Song 2007; Tak 2008), and two papers were conference abstracts superseded by another publication (Dougados 2007; Gnanasakthy 2013). We report details of the excluded studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables. Of the additional six studies identified through reference lists, five studies are awaiting classification until enough data is available to make a decision regarding inclusion (Elliott 1994; Kosinski 2000; St Clair 2004; Van der Kooij 2009; Westhovens 2006). We excluded the one remaining study, as fatigue was not an outcome measure and was a duplicate of a previously excluded study (Grigor 2004).

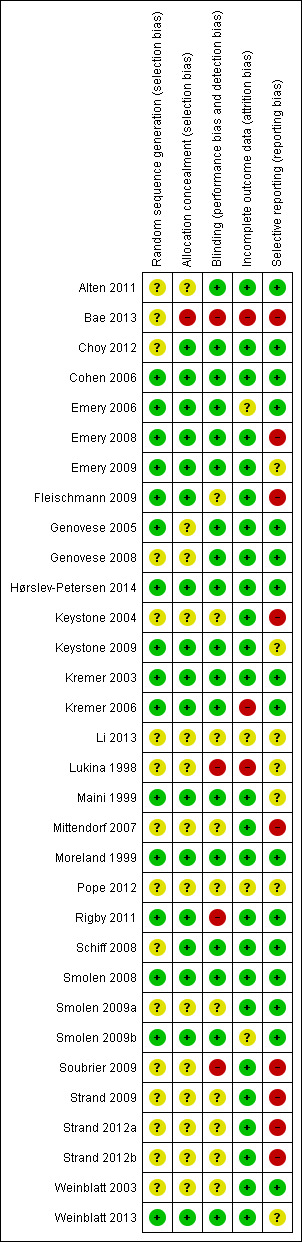

Risk of bias in included studies

Overall, for most of the included studies the risk of bias was low or unclear (Figure 2). However, for Lukina 1998, an early phase II trial of anti‐IFNγ monoclonal antibody, the risk of bias was high. This study did not provide any precision estimates on fatigue, so we did not include its results in the meta‐analyses of this review. Authors of study by Maini 1999 did not provide standard deviation so data from the study were not included in the meta‐analysis. Li 2013 and Pope 2012 were only available as conference abstracts, so carried a potential high risk of bias since details on randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding were not reported. Therefore, details on method of allocation, blinding and completeness of reporting could not be assessed adequately.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Investigators described all the studies as randomised controlled trials but did not report the method of randomisation in 12 studies.

Blinding

Investigators described all but two studies as double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trials (Lukina 1998; Bae 2013); however, 10 studies do not provide details.

Incomplete outcome data

Four studies did not provide sufficient details on attrition (Bae 2013; Li 2013; Lukina 1998; Pope 2012), and four studies did not account for a number of the participants who dropped out before the end of the studies (Emery 2006; Kremer 2003; Kremer 2006; Smolen 2009b).

Selective reporting

Selective reporting bias was a concern in four studies that either did not report details of improvement in fatigue or health‐related quality of life (HRQol) or did not report them at the primary endpoint of the trial (Emery 2008; Fleischmann 2009; Keystone 2004; Soubrier 2009) . Four studies described patient‐reported outcomes from previously published RCTs (Bae 2013; Strand 2009; Strand 2012a; Strand 2014).

Other potential sources of bias

In four studies, the lack of information on completeness of data from the questionnaire was a potential risk of bias (Emery 2006; Emery 2008, Lukina 1998; Maini 1999). Maini 1999 reported the second year result of a randomised controlled trial. After the first year, 94 participants had a treatment gap of over eight weeks, while the rest continued immediately into the second year. Those participants with the gap may have received other medications. Furthermore standard deviations of change were not provided by the authors. Lukina 1998 had no placebo control arm and had a very short‐term follow‐up as well as a very small sample size. Furthermore, authors did not provide the statistical analysis method or precision estimates. A funnel plot of all the studies did not suggest significant publication bias (Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 All Biologics, outcome: 1.1 All studies ‐ fatigue continuous measures.

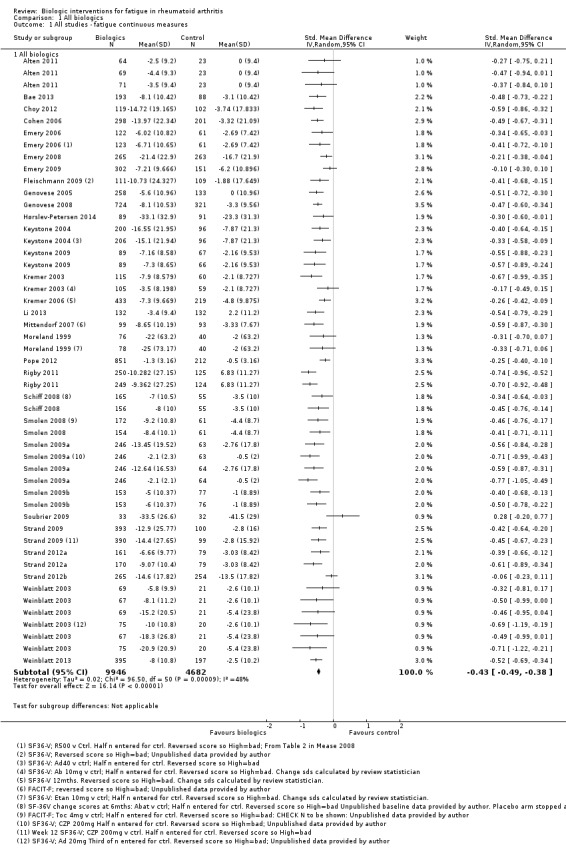

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Some of the trials were multidose trials and therefore provided at least two comparisons for the purpose of meta‐analyses. Data from Lukina 1998 and Maini 1999 did not contribute to the result of the meta‐analyses because the trial did not provide precision estimates, and there was no placebo control group. All the randomised placebo‐controlled trials reported statistically significant improvement in disease activity as well as pain score in the active treatment groups when compared with controls. Two studies did not use placebo controls (Bae 2013; Lukina 1998).

Primary outcomes

Self reported fatigue

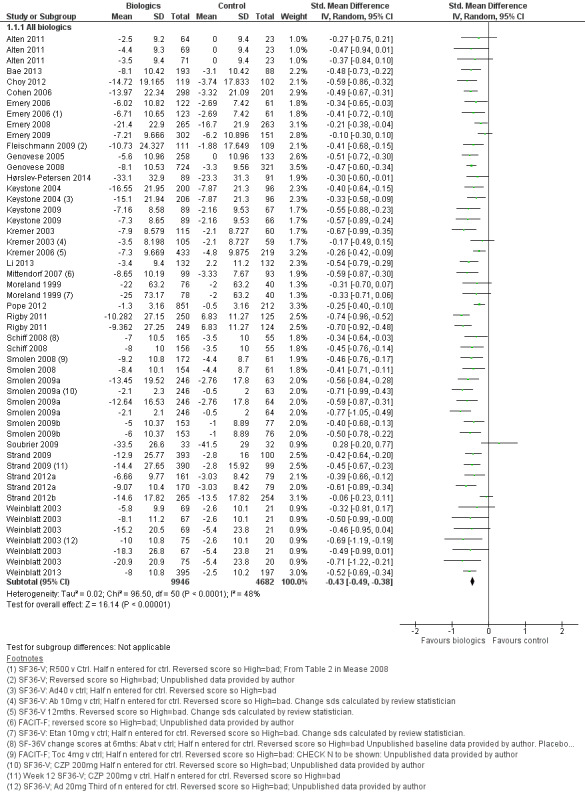

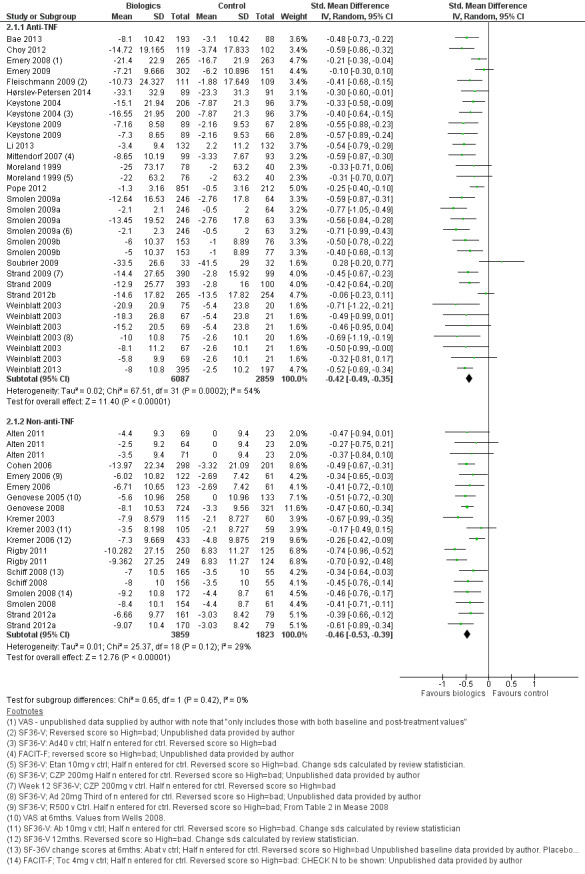

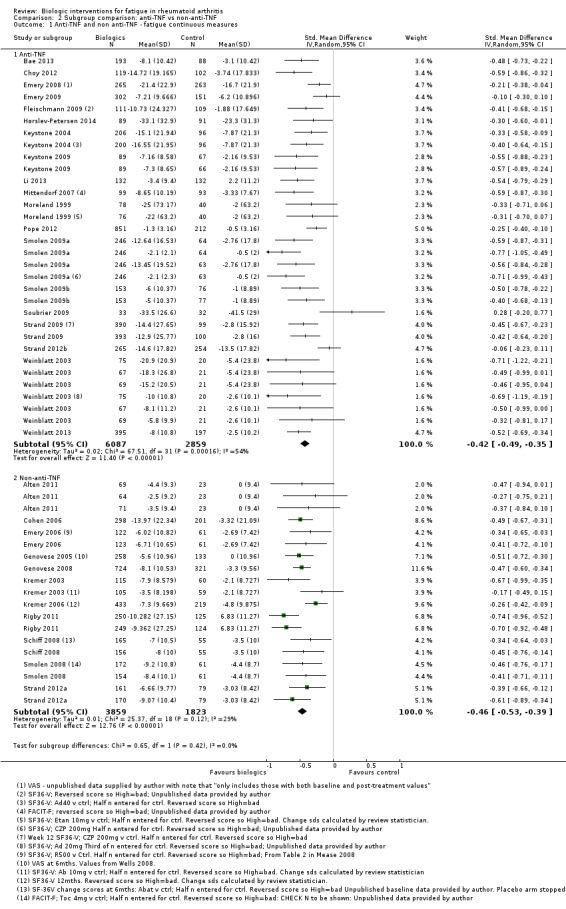

Overall treatment by biologic agents led to a statistically significant reduction in fatigue with an SMD of −0.43 (95% CI −0.49 to −0.38; P < 0.00001; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). There was statistically significant heterogeneity (I2 = 48%, P < 0.0001). Anti‐TNF biologic agents had an SMD of −0.42 (95% CI −0.49 to −0.35, P < 0.00001; Analysis 2.1; Figure 5) and non‐anti‐TNF agents had an SMD of −0.46 (95% CI −0.53 to −0.39; P < 0.00001; Analysis 4; Figure 5), showing similar effects on fatigue (Table 1). However, there was statistically significant heterogeneity in anti‐TNF trials (I2 = 54%, P = 0.0002). The precise cause of heterogeneity is unclear but may be due to different dosage, participant characteristics (early versus established disease), previous treatment (biologic naive versus failed biologic participants) and comorbidities that are associated with fatigue (e.g. depression).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 All biologics, Outcome 1 All studies ‐ fatigue continuous measures.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All Biologics, outcome: 1.1 All studies ‐ fatigue continuous measures.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Subgroup comparison: anti‐TNF vs non anti‐TNF, outcome: 4.1 Anti‐TNF and non anti‐TNF ‐ fatigue continuous measures.

We performed sensitivity analyses to explore the potential cause(s) of heterogeneity. Excluding dose‐ranging studies or trials in participants who had failed previous biologic therapy did not affect heterogeneity. Disease duration was, however, a significant factor. Five studies assessed the effect of anti‐TNF agents in early rheumatoid arthritis (Emery 2008; Hørslev‐Petersen 2014; Moreland 1999; Soubrier 2009; Strand 2012b). Excluding these studies reduced heterogeneity to statistical insignificance in the anti‐TNF meta‐analysis (I2 = 30%, P = 0.08). Most of the studies also reported significant improvement in disease activity as measured by ACR response criteria, disease activity score or both.

Secondary outcomes

Five studies did not report results of pain score, tender and swollen joints, or depression (Emery 2006; Kremer 2006; Maini 1999; Mittendorf 2007; Schiff 2008). All the other studies reported statistically significant reduction in pain score, physical function, and tender and swollen joint counts. However, improvement in pain was reported but data were not provided in many papers. Different pain instruments were used, visual analogue scale, SF‐36 bodily pain, numeric rating scale and percentage of patients with improvement in pain. Consequently, we were unable to pool data on pain for meta‐analysis. Most of the studies did not assess anxiety or depression. We could not determine whether reduction in fatigue is due to reduction in disease activity, pain, depression or a combination of these.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of this review was to provide an overview of the effects of biologic interventions on fatigue in people with RA. The review revealed 32 RCTs investigating biologic interventions and including fatigue as an outcome measure. There were two main categories of biologic interventions: anti‐TNF (20 studies) and non‐anti‐TNF biologics (12 studies). Overall the quality of the evidence was moderate. Both anti‐TNF and non‐anti‐TNF biologic treatments led to a small to moderate reduction in fatigue in participants with RA.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Randomised controlled trials of biologic agents for RA commonly assess fatigue. Clinical trials included in this review included all current biologic agents licensed for the treatment of RA. The magnitude of improvement is similar in the included studies. However, most of the studies were phase III trials conducted for the purpose of registration. Consequently, participants recruited into these trials had high disease activity, and the primary outcome measure was improvement in disease activity; change in fatigue was a secondary outcome measure. As the primary purpose of the interventions was not fatigue reduction, no consideration was given to factors that may confound or explain it, such as depression and reduced haemoglobin. Moreover, it is unclear whether improvement in fatigue was due to a reduction in overall disease activity or due to specific actions of the biologic agent. Analysis of fatigue in these studies did not make any adjustment for possible confounding factors such as change in pain, haemoglobin or mood. The duration of most of the double‐blind randomised controlled trials was 24 weeks or less. It is unclear whether improvement in fatigue is sustained with long‐term therapy. In these trials, recruited participants had highly active disease and moderate to high levels of fatigue at baseline. It is unclear whether biologic interventions improve fatigue in patients with moderate or low level of fatigue.

Quality of the evidence

Almost all the studies included are double‐blind, randomised placebo‐controlled trials. The quality of these trials was moderate, with highly variable reporting of fatigue using different measurement instruments. The SF‐36 VT was the most commonly used instrument. Many of these instruments were not developed specifically for assessing fatigue in RA, although they have been validated for assessing fatigue in other medical conditions and in general health. The use of the SF‐36 VT may also be questionable, as vitality may not be at the opposite end of the spectrum to fatigue. Consistent use of outcomes would simplify pooling of data and allow comparison between interventions.

Potential biases in the review process

There are two trials for which we failed to obtain data on fatigue from the authors; therefore there is some risk of reporting bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A recently published systematic review suggested that the biologic agents have a small to moderate effect in improving fatigue in RA, although it only included 10 studies (Chauffier 2012), all of which are included in this review. By including more studies, this Cochrane review reduces the risk of publication bias.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Treatment with biologic interventions in patients with active RA and moderate to high levels of fatigue may lead to a small to moderate improvement in fatigue. The magnitude of improvement is similar for anti‐TNF and non‐anti‐TNF biologic agents. However, it is unclear whether the improvement results directly from the biologic interventions on fatigue or indirectly through reduction in inflammation and disease activity.

Implications for research.

Future research needs to determine the mechanisms whereby biologic interventions reduce fatigue in patients with RA, in particular, to assess whether this is a direct or indirect effect of biologic agents through intermediary factors such as disease activity. In addition, it is important to assess whether the improvement in fatigue associated with biologic interventions observed in short‐term randomised controlled trials is maintained in the long term.

Acknowledgements

Louise Falzon, Trials Search Coordinator of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group, for providing assistance with the search strategy.

Eugene A. Sushchuk for invaluable help with translating a study from Russian.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

1. exp arthritis, rheumatoid/

2. ((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat$ or reumat$ or revmarthrit$) adj3 (arthrit$ or artrit$ or diseas$ or condition$ or nodule$)).tw.

3. 1 or 2

4. exp Fatigue/

5. fatigue$.tw.

6. (tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted).tw.

7. ((astenia or asthenic) and syndrome).tw.

8. ((lack or loss or lost) adj3 (energy or vigo?r)).tw.

9. (apath$ or lassitude or weak$ or letharg$).tw.

10. (feel$ adj3 (drained or sleep$ or sluggish)).tw.

11. vitality.tw.

12. or/4‐11

13. randomized controlled trial.pt.

14. controlled clinical trial.pt.

15. randomized.ab.

16. placebo.ab.

17. drug therapy.fs.

18. randomly.ab.

19. trial.ab.

20. groups.ab.

21. or/13‐20

22. (animals not (humans and animals)).sh.

23. 21 not 22

24. and/3,12,23

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

1 exp rheumatoid arthritis/

2 ((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat$ or reumat$ or revmarthrit$) adj3 (arthrit$ or artrit$ or diseas$ or condition$ or nodule$)).tw.

3 1 or 2

4 exp fatigue/

5 fatigue$.tw.

6 (tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted).tw.

7 ((astenia or asthenic) and syndrome).tw.

8 ((lack or loss or lost) adj3 (energy or vigo?r)).tw.

9 (apath$ or lassitude or weak$ or letharg$).tw.

10 (feel$ adj3 (drained or sleep$ or sluggish)).tw.

11 vitality.tw.

12 or/4‐11

13 3 and 12

14 random$.ti,ab.

15 factorial$.ti,ab.

16 (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab.

17 placebo$.ti,ab.

18 (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab.

19 (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab.

20 assign$.ti,ab.

21 allocat$.ti,ab.

22 volunteer$.ti,ab.

23 crossover procedure.sh.

24 double blind procedure.sh.

25 randomized controlled trial.sh.

26 single blind procedure.sh.

27 or/14‐26

28 exp animal/ or nonhuman/ or exp animal experiment/

29 exp human/

30 28 and 29

31 28 not 30

32 27 not 31

33 13 and 32

Appendix 3. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Arthritis, Rheumatoid explode all trees

#2 ((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat* or reumat* or revmarthrit*) near/3 (arthrit* or artrit* or diseas* or condition* or nodule*)):ti,ab

#3 (#1 OR #2)

#4 MeSH descriptor Fatigue explode all trees

#5 fatigue*:ti,ab

#6 (tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted):ti,ab

#7 ((astenia or asthenic) and syndrome):ti,ab

#8 ((lack or loss or lost) near/3 (energy or vigor)):ti,ab

#9 (apath* or lassitude or weak* or letharg*):ti,ab

#10 (feel* near/3 (drained or sleep* or sluggish)):ti,ab

#11 vitality:ti,ab

#12 (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11)

#13 (#3 AND #12)

Appendix 4. CINAHL search strategy

S75 S61 and S74

S74 S62 or S63 or S64 or S65 or S66 or S67 or S68 or S69 or S70 or S71 or S72 or S73

S73 TI Allocat* random* or AB Allocat* random*

S72 (MH "Quantitative Studies")

S71 (MH "Placebos")

S70 TI Placebo* or AB Placebo*

S69 TI Random* allocat* or AB Random* allocat*

S68 (MH "Random Assignment")

S67 TI Randomi?ed control* trial* or AB Randomi?ed control* trial*

S66 AB singl* blind* or AB singl* mask* or AB doub* blind* or AB doubl* mask* or AB trebl* blind* or AB trebl* mask* or AB tripl* blind* or AB tripl* mask*

S65 TI singl* blind* or TI singl* mask* or TI doub* blind* or TI doubl* mask* or TI trebl* blind* or TI trebl* mask* or TI tripl* blind* or TI tripl* mask*

S64 TI clinical* trial* or AB clinical* trial*

S63 PT clinical trial

S62 (MH "Clinical Trials+")

S61 S42 and S60

S60 S43 or S44 or S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 or S49 or S50 or S51 or S52 or S53 or S54 or S55 or S56 or S57 or S58 or S59

S59 ti vitality or ab vitality

S58 ab feel* N3 drain* or ab feel* N3 sleep* or ab feel* N3 sluggish

S57 ti feel* N3 drain* or ti feel* N3 sleep* or ti feel* N3 sluggish

S56 ab apath* or ab lassitude or ab weak* or ab letharg*

S55 ti apath* or ti lassitude or ti weak* or ti letharg*

S54 ab lack N3 vigour or abloss N3 vigour or ab lost N3 vigour

S53 ti lack N3 vigour or ti loss N3 vigour or ti lost N3 vigour

S52 ab lack N3 vigor or ab loss N3 vigor or ab lost N3 vigor

S51 ti lack N3 vigor or ti loss N3 vigor or ti lost N3 vigor

S50 ti lack N3 vigor or ti loss N3 vigor or ab lost N3 vigor

S49 ti lack N3 energy or ti loss N3 energy or ti lost N3 energy

S48 ab astenia syndrome or ab asthenic syndrome

S47 ti astenia syndrome or ti asthenic syndrome

S46 ab tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted

S45 ti tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted

S44 ti fatigue* or ab fatigue*

S43 (MH "Fatigue+")

S42 S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 or S34 or S35 or S36 or S37 or S38 or S39 or S40 or S41

S41 TI reumat* N3 nodule* or AB reumat* N3 nodule*

S40 TI reumat* N3 condition* or AB reumat* N3 condition*

S39 TI reumat* N3 diseas* or AB reumat* N3 diseas*

S38 TI reumat* N3 artrit* or AB reumat* N3 artrit*

S37 TI reumat* N3 arthrit* or AB reumat* N3 arthrit*

S36 TI revmarthrit* N3 nodule* or AB revmarthrit* N3 nodule*

S35 TI revmarthrit* N3 condition* or AB revmarthrit* N3 condition*

S34 TI revmarthrit* N3 diseas* or AB revmarthrit* N3 diseas*

S33 TI revmarthrit* N3 artrit* or AB revmarthrit* N3 artrit*

S32 TI revmarthrit* N3 arthrit* or AB revmarthrit* N3 arthrit*

S31 TI rheumat* N3 nodule* or AB rheumat* N3 nodule*

S30 TI rheumat* N3 condition* or AB rheumat* N3 condition*

S29 TI rheumat* N3 diseas* or AB rheumat* N3 diseas*

S28 TI rheumat* N3 artrit* or AB rheumat* N3 artrit*

S27 TI rheumat* N3 arthrit* or AB rheumat* N3 arthrit*

S26 TI revmatic N3 nodule* or AB revmatic N3 nodule*

S25 TI revmatic N3 condition* or AB revmatic N3 condition*

S24 TI revmatic N3 diseas* or AB revmatic N3 diseas*

S23 TI revmaticN3 artrit* or AB revmatic N3 artrit*

S22 TI revmatic N3 arthrit* or AB revmatic N3 arthrit*

S21 TI rheumatic N3 nodule* or AB rheumatic N3 nodule*

S20 TI rheumatic N3 condition* or AB rheumatic N3 condition*

S19 TI rheumatic N3 diseas* or AB rheumatic N3 diseas*

S18 TI rheumatic N3 artrit* or AB rheumatic N3 artrit*

S17 TI rheumatic N3 arthrit* or AB rheumatic N3 arthrit*

S16 TI revmatoid N3 nodule* or AB revmatoid N3 nodule*

S15 TI revmatoid N3 condition* or AB revmatoid N3 condition*

S14 TI revmatoid N3 diseas* or AB revmatoid N3 diseas*

S13 TI revmatoid N3 artrit* or AB revmatoid N3 artrit*

S12 TI revmatoid N3 arthrit* or AB revmatoid N3 arthrit*

S11 TI reumatoid N3 nodule* or AB reumatoid N3 nodule*

S10 TI reumatoid N3 condition* or AB reumatoid N3 condition*

S9 TI reumatoid N3 diseas* or AB reumatoid N3 diseas*

S8 TI reumatoid N3 artrit* or AB reumatoid N3 artrit*

S7 TI reumatoid N3 arthrit* or AB reumatoid N3 arthrit*

S6 TI rheumatoid N3 nodule* or AB rheumatoid N3 nodule*

S5 TI rheumatoid N3 condition* or AB rheumatoid N3 condition*

S4 TI rheumatoid N3 diseas* or AB rheumatoid N3 diseas*

S3 TI rheumatoid N3 artrit* or AB rheumatoid N3 artrit* *

S2 TI rheumatoid N3 arthrit* or AB rheumatoid N3 arthrit*

S1 (MH "Arthritis, Rheumatoid+")

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

1. rheumatoid arthritis/

2. ((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat$ or reumat$ or revmarthrit$) adj3 (arthrit$ or artrit$ or diseas$ or condition$ or nodule$)).tw.

3. 1 or 2

4. Fatigue/

5. fatigue$.tw.

6. (tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted).tw.

7. ((astenia or asthenic) and syndrome).tw.

8. ((lack or loss or lost) adj3 (energy or vigo?r)).tw.

9. (apath$ or lassitude or weak$ or letharg$).tw.

10. (feel$ adj3 (drained or sleep$ or sluggish)).tw.

11. vitality.tw.

12. or/4‐11

Appendix 6. AMED search strategy

1. exp arthritis, rheumatoid/

2. ((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat$ or reumat$ or revmarthrit$) adj3 (arthrit$ or artrit$ or diseas$ or condition$ or nodule$)).tw.

3. 1 or 2

4. exp Fatigue/

5. fatigue$.tw.

6. (tired$ or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted).tw.

7. ((astenia or asthenic) and syndrome).tw.

8. ((lack or loss or lost) adj3 (energy or vigo?r)).tw.

9. (apath$ or lassitude or weak$ or letharg$).tw.

10. (feel$ adj3 (drained or sleep$ or sluggish)).tw.

11. vitality.tw.

12. or/4‐11

13. 3 and 12

Appendix 7. Web of Science search strategy

Topic=((rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat* or reumat* or revmarthrit*) and (arthrit* or artrit* or diseas* or condition* or nodule*)) AND Topic=(fatigue* or tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or astenia syndrome or asthenic syndrome or apath* or

lassitude or weak* or

(lack or loss or lost) and (letharg* or energy or vigoor* or vigour*) or

Feel* and (drained or sleep* or sluggish)

(trial* or random* or placebo* or control* or double or treble or triple or blind* or mask* or allocat* or prospective* or volunteer*or comparative or evaluation or follow‐up or followup)

Appendix 8. Dissertation Abstracts search strategy

(rheumatoid or reumatoid or revmatoid or rheumatic or reumatic or revmatic or rheumat* or reumat* or revmarthrit*) in citation and abstract

AND (fatigue* or tired* or weary or weariness or exhaustion or exhausted or astenia syndrome or asthenic syndrome or apath* or lassitude or weak* or letharg* or energy or vigoor* or vigour* or drained or sleep* or sluggish) in citation and abstract

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. All biologics.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All studies ‐ fatigue continuous measures | 30 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 All biologics | 30 | 14628 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐0.49, ‐0.38] |

Comparison 2. Subgroup comparison : anti‐TNF vs non‐anti‐TNF.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Anti‐TNF and non anti‐TNF ‐ fatigue continuous measures | 30 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Anti‐TNF | 19 | 8946 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.42 [‐0.49, ‐0.35] |

| 1.2 Non‐anti‐TNF | 11 | 5682 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.46 [‐0.53, ‐0.39] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Subgroup comparison : anti‐TNF vs non‐anti‐TNF , Outcome 1 Anti‐TNF and non anti‐TNF ‐ fatigue continuous measures.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alten 2011.

| Methods | RCT of 12 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinics, Multicentre international Males or females ≥ 18 years of age Revised 1987 ACR classification criteria for RA, symptoms for ≥ 3 months Active RA, defined as ≥ 6/28 tender and swollen joints with CRP ≥ 10 mg/L, erythrocyte sedimentation ≥ 28 mm or both ACR Functional status classes I, II, or III Treated with methotrexate at the maximum tolerated dose (≤ 25 mg/week) and at a stable dose of ≥ 7.5 mg/week for ≥ 12 weeks. Patients who had failed treatment with any DMARD, including any such agent used in combination with methotrexate as well as any biologic agent, were eligible for participation after an appropriate washout period. Systemic corticosteroids, NSAIDs, including cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibitors or paracetamol, had to have been stable doses for at least 4 weeks. Maximum allowable dose of systemic corticosteroids was ≤ 10 mg/day prednisone or an equivalent for ≥ 4 weeks. Group 1‐4: Percentage Female: 81.2%, 89.1%, 84.5% and 74.3% respectively Age, mean (SD) years: 57.10 (11.899), 61.02 (12.244), 55.62 (11.236), 57.53 (12.121) respectively Exclusion Previous hypersensitivity to the study drug or to molecules with similar structures Intra‐articular therapy for RA within the previous 4 weeks Pregnant or breastfeeding Positive TB skin test without a follow‐up negative chest X‐ray |

|

| Interventions | Group 1: canakinumab 150 mg subcutaneously (SC) every 4 weeks + MTX

Group 2: canakinumab 300 mg SC every 2 weeks + MTX

Group 3: canakinumab 600 mg IV loading dose followed by 300 mg SC every 2 weeks + MTX Group 4: Placebo subcutaneously every 2 weeks + MTX |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: response to treatment according to ACR 50 criteria at 12 weeks

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Exclusions | Previous hypersensitivity to the study drug or to molecules with similar structures Intra‐articular therapy for RA within the previous 4 weeks Pregnant or breastfeeding Positive TB skin test without a follow‐up negative chest X‐ray | |

| Fatigue outcomes | FACIT, 0‐52, high = good | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomised in a double‐blind fashion |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomised in a double‐blind fashion |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Randomised in a double‐blind fashion |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | ITT |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Fatigue was reported in the main study report |

Bae 2013.

| Methods | RCT of 16 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinics Multicentre, Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, Korea and Thailand. RA, based on 1987 ACR criteria 28‐joint Disease Activity Score [DAS28] ≥3.2, who displayed inadequate response to oral MTX (stable dosing between 7.5 mg/week and 25 mg/week for minimum 3 months ETN + MTX group: 91.4% female, mean age (± SD) 48.4 years ± 12.0 DMARD+MTX group: 88.4% female, mean age (± SD) 48.5 years ± 11.3, Exclusion Not stated |

|

| Interventions | Subcutaneous etanercept (ETN) 25 mg per injection twice weekly was added to methotrexate (MTX). MTX according to local use, orally, weekly mean dose was 12.9 mg (1.9 mg‐25 mg) Patients were randomized to either of two treatment groups in an approximate 2:1 ratio: 1. ETN+MTX (N= 197) or 2. DMARD +MTX (N= 103). DMARD therapy (defined as the addition of DMARD investigator’s choice to MTX) followed the standard of care and approved local label or recommendations; the three most frequently used DMARDs in the study were leflunomide (n = 69), sulfasalazine (n = 23) and hydroxychloroquine (n = 11). |

|

| Outcomes | Primary Outcome: ACR response Secondary Outcomes 1. Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) ranges 0 (best) ‐ 3 (worse). 2. SF‐36 in eight domains: bodily pain, general health, physical functioning, role‐physical, mental health, role‐emotional, social functioning and vitality. SF‐36 scores range from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) for each of the eight domains. 3. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) ranges 0 (best) to 3 (worst) 4. FACIT‐F Scale. Scores range from 0 to 52, with higher scores indicating less fatigue. 5. Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: General Health (WPAI:GH) measures percentage impairment of usual activities and percentage impairment of work and productivity due to health, with higher scores reflecting higher percentage impairment. All assessments were carried out at baseline, week 8 and 16 |

|

| Exclusions | Not stated | |

| Fatigue outcomes | Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) NRS, 0‐10, high = bad, SF‐36 vitality | |

| Notes | This is patient‐reported outcome paper, earlier paper reported the main study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported in the text |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Open‐label |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | SD are not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | This is patient‐reported outcome paper, earlier paper reported the main study |

Choy 2012.

| Methods | RCT of 24 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinic, Multicentre international Inclusion criteria Aged 18‐75 years Adult‐onset RA of at least 6 months as defined by the 1987 ACR criteria Active disease defined as > 9 tender joints, > 9 swollen joints and at least 1 of the 3 following criteria: > 45 min EMS, ESR > 28 mm/h or CRP > 10 mg/L Receiving MTX for at least 6 months and on a stable dosage of 15‐25 mg/week for at least 8 weeks (10‐15 mg/week was deemed acceptable in cases where a dosage reduction had been necessary because of toxicity). All other DMARDs were to have been discontinued at least 28 days before the first study medication dose. Exclusion Any form of inflammatory arthritis other than RA History of chronic, serious or life‐threatening infection, current infection History or chest X‐ray suggestive of tuberculosis, or positive (defined per local medical practice) purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test (Mantoux) History of infected joint prosthesis IM, IV or IA CSs or IA hyaluronic acid in the 4 weeks preceding the study Prior treatment with any TNF‐ɑ inhibitor Receipt of any experimental, unregistered or biological therapy in the 6 months preceding the study NSAIDs and oral CSs at a dosage of < 10 mg/day prednisone equivalent were allowed if stable for > 4 weeks before study entry and thereafter Analgesics not allowed during the 4 days preceding baseline assessment, except paracetamol, which was not allowed within 24 h Group 1 and 2: Gender (percentage female): 72.2% and 66.1% respectively Age, mean (S.D.), years 53.0 (12.3) and 55.6 (11.7) respectively |

|

| Interventions | SC reconstituted lyophilised CZP 400 mg or placebo every 4 weeks from baseline to week 20. MTX 15‐25 mg/week (10‐15 mg/week was allowed if the dose had been reduced because of toxicity). Group 1: CZP + MTX Group 2: Placebo + MTX |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: ACR 20 response rate at week 24

Secondary outcomes:

Assessments of endpoints at weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 22 and 24 |

|

| Exclusions | Any form of inflammatory arthritis other than RA History of chronic, serious or life‐threatening infection, current infection History or chest X‐ray suggestive of tuberculosis, or positive (defined per local medical practice) purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test (Mantoux) History of infected joint prosthesis IM, IV or IA CSs or IA hyaluronic acid in the 4 weeks preceding the study Prior treatment with any TNF‐ɑ inhibitor Receipt of any experimental, unregistered or biological therapy in the 6 months preceding the study NSAIDs and oral CSs at a dosage of < 10 mg/day prednisone equivalent were allowed if stable for > 4 weeks before study entry and thereafter Analgesics not allowed during the 4 days preceding baseline assessment, except paracetamol, which was not allowed within 24 h | |

| Fatigue outcomes | SF‐36, 0‐100, high = good | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Patients were randomised on a 1:1 basis via an interactive voice‐response system |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Patients were randomised on a 1:1 basis via an interactive voice‐response system |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | To preserve the blind to clinical research staff, the study site pharmacist labelled clinical supplies (study medication syringes), and a sorbitol placebo was used to match the viscosity of CZP. Placebo injections |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Efficacy evaluations were carried out in the modified intention‐to‐treat (mITT) population, defined as all randomised patients who had taken at least 1 dose of study medication. For continuous data, missing data were imputed by last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Fatigue was reported in the main study report |

Cohen 2006.

| Methods | RCT of 24 weeks, followed up until week 104 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinic, multicentre international Inclusion 18‐80 years, active RA (≥ 8 swollen or tender joints), RA minimum 6 months, non‐response to anti‐TNF, taking MTX for minimum 12 weeks prior to screening Exclusion Significant systemic involvement secondary to RA, ACR functional class IV Group 1 and 2: Gender (percentage female): 81% and 81% respecitively Age (mean (SD) years): 52.8 (12.6), 52.2 (12.2) respecitively |

|

| Interventions | Rituximab 1000 mg on days 1 and 15 or placebo

MTX (10‐25 mg/week orally or parenterally), folate (≥ 5 mg/week), IV methylprednisolone (100 mg 30 min before infusion) and oral prednisolone (60 mg on days 2‐7, 30 mg on days 8‐14) Group 1: Placebo + MTX Group 2: RTX + MTX |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: ACR 20 response at week 24

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Exclusions | Significant systemic involvement secondary to RA, ACR functional class IV | |

| Fatigue outcomes | FACIT‐F, range 0‐52, high = bad SF‐36 VT, 0‐100, high = good | |

| Notes | Keystone 2008 provided further data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | "Patients were randomised at a ratio of 3:2" |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Patients were randomised at a ratio of 3:2" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Blinded study with the study sponsor, investigators and patients unaware of the treatment assignment of each patient" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | ITT population was defined as all randomised patients who received any part of an infusion of study medication and included patients who withdrew prematurely from the study for any reason and for whom assessments were not made. Last observation carried forward |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Fatigue was reported in the main study report |

Emery 2006.

| Methods | 3 x 3 factorial RCT of 24 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinic, Multicentre international Inclusions 18‐80 years, active RA (≥ 8 swollen or tender joints/CRP ≥ 1.5 mg/dL or ESR ≥ 28mm/h) despite MTX. Failed 1‐5 DMARDS or biologic agents, glucocorticoids ≤ 10 mg/day, RF positive Exclusions Significant systemic RA, other illness or lab abnormalities, recurrent significant infections, prior rituximab, allergy to agents Gender Placebo (percentage female): 80% (placebo), 83% (RTX 2x500mg) and 80% (RTX 2x1000mg) Age (mean years): 51.1 (placebo) 51.4 (RTX 2x500mg) and 51.1 (RTX 2x1000mg) |

|

| Interventions | All patients received MTX (10–25 mg/week); no other DMARDs were permitted RTX IV infusion on day 1 and 15. 9 Groups 1. RTX 2 x 500 mg + placebo glucocorticoid on days 1 and 15 2. RTX 2 x 500 mg + 100 glucocorticoid on day 1 and 15 3. RTX 2 x 500 mg + IV methylprednisolone premedication + oral prednisone for 2 weeks 4. RTX 2 x 1000 mg + placebo glucocorticoid on days 1 and 15 5. RTX 2 x 1000 mg + 100 glucocorticoid on days 1 and 15 6. RTX 2 x 1000 mg + intravenous methylprednisolone premedication + oral prednisone for 2 weeks 7. Pacebo 2 x infusion + placebo glucocorticoid on days 1 and 15 8. Placebo 2 x infusion + 100 glucocorticoid on days 1 and 15 9. Placebo 2 x infusion + intravenous methylprednisolone premedication + oral prednisone for 2 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: ACR 20 at 24 week Secondary outcomes: ACR50, 70 EULAR response HAQ‐DI SF‐36 FACIT‐F safety All assessments at baseline and week 24 |

|

| Exclusions | Significant systemic RA, other illness or lab abnormalities, recurrent significant infections, prior rituximab, allergy to agents | |

| Fatigue outcomes | FACIT‐F, range 0‐52, high = good SF‐36 VT, high = good | |

| Notes | Fatigue was reported in the main study report | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomised control trial |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | "Double‐blind, double‐dummy" |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | "Double‐blind, double‐dummy" |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Dropouts "failed" |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Fatigue was reported in the main study report |

Emery 2008.

| Methods | RCT of 52 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinics Multicentre, international in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Australia Inclusions 18 years or older, diagnosis of adult‐onset rheumatoid arthritis, disease duration minimum 3 months maximum 2 years, DAS 28 of 3.2 or more, and either Westergren ESR of ≥ 28 mm/h or CRP of ≥ 20 mg/L Exclusions Previous treatment with MTX, etanercept, or another TNF antagonist at any time or treatment with other DMARDs or corticosteroid injections in the 4 weeks before baseline visits. Individuals with important concurrent medical diseases were ineligible, as were those with other relevant comorbidities. Group 1 and 2: Gender (percentage female): 73% and 74% respecitively Age (mean (SD) years): 52.3 (0.8), 50.5 (0.9) respecitively |

|

| Interventions | All participants received oral methotrexate, starting at 7.5 mg once a week. ETN 50 mg by subcutaneous injection once a week for 52 weeks. In patients with tender or swollen joints, the dose was titrated up over 8 weeks to a maximum of 20 mg a week Group 1: Placebo+ MTX Group 2: ETN + MTX |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes:

Secondary outcomes (at weeks 12, 24, 36 and 52):

|

|

| Exclusions | Previous treatment with MTX, etanercept, or another TNF antagonist at any time or treatment with other DMARDs or corticosteroid injections in the 4 weeks before baseline visits. Individuals with important concurrent medical diseases were ineligible, as were those with other relevant comorbidities. | |

| Fatigue outcomes | Fatigue VAS, 0‐100, high = bad SF‐36 VT, 0‐100, high = good | |

| Notes | For all patients stable doses of oral corticosteroids (≤ 10 mg per day of prednisone or an equivalent agent) or a single non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug were permitted if started at least 4 weeks before baseline and kept constant throughout the first 24 weeks of the study. After completion of 24 weeks of treatment, reductions in dose of prednisone or other oral corticosteroid by 1 mg per day or less were allowed every week. Oral corticosteroids were tapered to 3 mg per day or less before the dose of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug was decreased. All patients received folic acid supplementation of 5 mg twice weekly (not given on the same day as methotrexate) to reduce side effects associated with methotrexate. Fatigue data reported in Kekow 2010. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were randomly assigned with a computerised randomisation and enrolment (CORE) system to generate and implement allocation sequence, manage assignment to treatment groups, and maintain blinding. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were randomly assigned with a computerised randomisation and enrolment (CORE) system to generate and implement allocation sequence, manage assignment to treatment groups, and maintain blinding. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Data were unblinded only if needed for medical management of patients. Masking was removed for one sponsor biostatistical programmer to do the 52‐week primary analysis for this report |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | ITT/LOCF |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | results of employment questionnaire were not reported |

Emery 2009.

| Methods | RCT of 24 week | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinic, Multicentre international Inclusions Adults who had RA, according to ACR criteria for at least 3 months Had not received more than 3 weekly doses of oral MTX as treatment of RA Active RA, with at least 4 swollen joints and at least 4 tender joints AND at least 2 of the following.

Prespecified TB screening criteria. Patients with positive results for TB skin or whole blood interferon‐γ–based QuantiFERON‐TB testing could participate but had to start prophylaxis for latent TB before or simultaneously with administration of the first dose of the study agent. Concurrent use of NSAIDs, other analgesics for RA, and oral corticosteroids (< 10 mg of prednisone/day or equivalent) was allowed if doses were stable for > 2 weeks Patients receiving anakinra could participate 4 weeks after receiving the last dose Patients receiving alefacept or efalizumab could participate 3 months after receiving the last dose Patients receiving an experimental agent could participate after the equivalent of 5 half‐lives of the agent Exclusions Patients who had previously received infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab, natalizumab or cytotoxic agents, including chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, nitrogen mustard, and other alkylating agents, were excluded. Group 1, 2 3, and 4 Gender (percentage female): 83.8%, 84.3%, 84.9% and 78.6% respectively Age, mean (SD) years: 48.6 (12.91), 48.2 (12.85), 50.9 (11.32) and 50.6 (11.58) |

|

| Interventions | Golimumab subcutaneously at week 0 and then every 4 weeks

MTX started at 10 mg/week at week 0 and escalated by 2.5 mg every 2 weeks to 20 mg/week by week 8

Duration of intervention = 24 weeks reported here (but 52 weeks plus 5 years open label extension) Group 1: placebo by SC injection plus MTX Group 2: golimumab 100 mg by SC injection plus placebo capsules Group 3: golimumab 50 mg by SC injection plus MTX capsules Group 4: golimumab 100 mg by SC injection plus MTX capsules |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: difference in the ACR 50 response at week 24 between groups 3 and 4 combined (combined group) versus group 1 and a pairwise comparison (group 3 or group 4 versus group 1).

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Exclusions | Patients who had previously received infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, rituximab, natalizumab or cytotoxic agents, including chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, nitrogen mustard, and other alkylating agents, were excluded. | |

| Fatigue outcomes | SF‐36 VT. 0‐100, high = good | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | An interactive voice response system (IVRS) was used to randomly assign eligible patients to 1 of 4 treatment groups in approximately equal proportions |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | IVRS was used to randomly assign eligible patients to 1 of 4 treatment groups in approximately equal proportions |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Golimumab and placebo were supplied as sterile liquid (aqueous medium of histidine, sorbitol, and polysorbate 80 (pH 5.5) with or without golimumab) for SC injection. Active and placebo MTX were supplied as double‐blinded, identical opaque capsules (filled with microcrystalline cellulose with or without MTX). An independent assessor at each study centre, who had no access to patient records and no other role in the study, performed the joint assessments. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All randomised patients (all of those who were entered in the IVRS for randomisation regardless of receipt of study treatment) were analysed by assigned treatment group (ITT) approach. Patients for whom all week 24 (the primary end point visit) ACR component data were missing were considered non‐responders, as were patients meeting predefined treatment failure criteria related to prohibited concomitant medications or discontinuation of the SC study agent due to lack of efficacy. Actual week 24 data were used for patients who discontinued the study agent for reasons other than lack of efficacy but returned for clinical evaluations, but these patients were considered non‐responders if they met any of the treatment failure criteria |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Main paper, methods section does not say whether fatigue and SF‐36 data are collected, but these are presented in a later paper |

Fleischmann 2009.

| Methods | RCT of 24 weeks | |

| Participants | Outpatient clinic, Multicentre international Inclusion criteria 18‐75 years, adult onset RA minimum 6 months, failed ≥1 DMARD, active disease ≥ 9 (out of 68) tender joints and ≥ 9 (out of 66) swollen joints and ≥ 1 of the following: > 45 min of morning stiffness, ESR ≥ 28 mm/h, CRP > 10 mg/L Exclusions Any inflammatory arthritis other than RA, history of chronic, serious or life‐threatening infection, any current infection, history of or a chest x ray suggesting tuberculosis or a positive PPD skin test, patients who received biological therapies for RA within 6 months, prior treatment with TNF‐α inhibitors, intra‐articular, periarticular, intramuscular and intravenous corticosteroids Group 1 and 2 Gender (percentage female): 89%and 78.4% respectively Age, mean (SD) years: 54.9 (11.6) and 52.7 (12.7) respectively |

|

| Interventions | 400 mg SC certolizumab pegol Group 1: Placebo SC Group 2: Certolizumab pegol SC |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: ACR 20 response at 24 weeks Secondary outcomes at week 24:

|

|

| Exclusions | Any inflammatory arthritis other than RA, history of chronic, serious or life‐threatening infection, any current infection, history of or a chest x ray suggesting tuberculosis or a positive PPD skin test, patients who received biological therapies for RA within 6 months, prior treatment with TNF‐α inhibitors, intra‐articular, periarticular, intramuscular and intravenous corticosteroids | |

| Fatigue outcomes | SF‐36 VT, 0‐100, high = good Fatigue Assessment Scale, 11‐point scale, high = bad | |

| Notes | — | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Interactive voice randomisation service |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Interactive voice randomisation service |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Intervention and placebo solutions were administered by blinded study personnel. No details given about outcome assessors |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Modified ITT for all efficacy analyses |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Health‐related quality of life data not shown but improvements claimed. SF‐36 data not published but have been provided subsequently |

Genovese 2005.

| Methods | RCT of 6 months | |