Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with Truvada has emerged as an increasingly common approach to HIV prevention among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. This study examined generational differences and similarities in narrative accounts of PrEP among a diverse sample of 89 gay and bisexual men in the United States. Over 50% of men in the older (52–59 years) and younger (18–25 years) generations endorsed positive views, compared with 32% of men in the middle (34–41 years) generation. Men in the middle cohort expressed the most negative (21%) and ambivalent (47%) views of PrEP. Thematic analysis of men’s narratives revealed three central stories about the perceived impact of PrEP: (1) PrEP has a positive impact on public health by preventing HIV transmission (endorsed more frequently by men in the older and younger cohorts); (2) PrEP has a positive effect on gay and bisexual men’s sexual culture by decreasing anxiety and making sex more enjoyable (endorsed more frequently by men in the middle and younger cohorts); and (3) PrEP has a negative impact on public health and sexual culture by increasing condomless, multi-partner sex (endorsed more frequently by men in the middle and younger cohorts). Results are discussed in terms of the significance of generation-cohort in meanings of sexual health and culture and implications for public health approaches to PrEP promotion among gay and bisexual men.

Keywords: PrEP, HIV/AIDS, gay men, public health, narrative, sexual culture

INTRODUCTION

Nearly 30 years after the identification of the first cases of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and its causal agent, the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), a prevention breakthrough emerged with the discovery of the effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis using Truvada (PrEP; Grant et al., 2010). This discovery occurred at a critical point in the containment of the virus among gay and bisexual men, as rates of new infection had been steadily on the rise and condomless sex (“barebacking”) was becoming increasingly common (e.g., Carballo-Diéguez & Bauermeister, 2004; Halkitis & Parsons, 2003; Halkitis, Parsons, & Wilton, 2003). This shift in the sexual culture of gay and bisexual men likely reflected a complacency about HIV, with treatment advances having transformed the virus from a lethal diagnosis to a chronic, manageable health condition (Halkitis et al., 2003), as well as a desire for enhanced intimacy through sex absent barriers (Carballo-Diéguez & Bauermeister, 2004; Halkitis et al., 2003). Early studies of barebacking revealed that most men were practicing what they believed to be an effective form of risk reduction by “serosorting” (i.e., engaging in condomless sex only with men of the same HIV serostatus; e.g., Halkitis, Wilton, & Galatowitsch, 2005).

A new generation of gay and bisexual men born in the early 1990s had not witnessed the devastation of the epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s (Hammack, Frost, Meyer, & Pletta, 2018) and were seroconverting at concerning rates (e.g., Grulich & Kaldor, 2008). Their norms around sex appeared to diverge from older men, a group that had been socialized into a culture promoting safer sex through condom use. Older generations of men who had been vigilant about condom use for decades also experienced “condom fatigue” as the meaning of HIV shifted, opting to forego condoms and thus risking HIV infection (Halkitis et al., 2003).

This brief account grounds the emergence of PrEP in a historical moment but also highlights the way in which gay and bisexual men of distinct birth cohorts may diverge in their understanding of sex and sexual culture because of their distinct relations to AIDS (Halkitis, 2014; Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). A recent study using a nationally representative sample of gay and bisexual men in the United States (USA) revealed differences in HIV testing and familiarity with PrEP across cohorts (Hammack, Meyer, Krueger, Lightfoot, & Frost, 2018). The study discovered that younger men (ages 18–25) and older men (ages 52–29) were less familiar with PrEP than men ages 34–41, and 25% of younger men had never been tested for HIV (Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018). Recent epidemiological research revealed that gay and bisexual men under 34 account for 64% of new HIV infections, while rates of infection have decreased or remained stable for older cohorts of men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). These findings highlight the value of examining differences in HIV prevention strategies across age cohorts, with a particular eye toward younger men.

As part of a larger study examining generational differences in identity, stress, and health among sexual minorities in the USA, this article examines differences and similarities across three birth cohorts of gay and bisexual men in the meaning and significance of PrEP. We sought to examine the way in which narrative accounts of PrEP converged or diverged across generations in terms of (a) men’s overall attitudes toward PrEP, (b) their perceptions of the impact of PrEP on public health, and (c) their perceptions of the impact of PrEP on sexual culture. We sought to reveal the way in which a paradigm that foregrounds the significance of narrative and generation-cohort challenges notions of gay and bisexual men as a monolithic social category (Hammack, 2018; Hammack, Frost et al., 2018), as well as to produce knowledge that can be used to enhance HIV prevention efforts by responding to diverse understandings of PrEP.

Sexual Culture and the Course of Gay and Bisexual Men’s Lives

Following early attempts to construct universal stage-based concepts of sexual minority identity development (e.g., Cass, 1979; Troiden, 1979), a new paradigm for sexual orientation has gradually emerged that better accommodates sensitivity to social and cultural change in the diverse settings in which lives unfold. A life course narrative paradigm emphasizes the way in which sexual identity development occurs through a dynamic engagement with stories about sexual and gender diversity that proliferate in cultures at particular historical moments (Cohler & Hammack, 2007; Hammack & Cohler, 2009, 2011; Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). This paradigm sensitizes us to both the historical context of development and the timing of exposure to narratives at particular moments in life. For example, gay and bisexual men born in the 1990s and today in early adulthood experienced adolescence during the marriage equality movement and may be more likely to see their same-sex attraction as indicative of a normative form of sexual diversity compared with prior generations of men (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). Men born in the late 1970s and early 1980s and today in their thirties and early forties, by contrast, experienced their adolescence in the 1990s, when homosexuality remained highly stigmatized in US society. Men of this generation might be more likely to have immersed themselves in sexual minority communities as a buffer against the potential negative effects of minority stress (see Meyer, 2003).

A life course narrative paradigm proposes that social change in the cultural meaning of identities and practices can produce diversity in development across generations. In the case of gay and bisexual men’s health and identity, we suggest that this social change has been significant over the past half-century and has resulted in a proliferation of discourses related to health and identity. The way in which diverse groups of men engage with these discourses is a goal of empirical study (Hammack, 2018; Hammack, Frost et al., 2018).

In the current study, we identified three distinct generations of gay and bisexual men whose experience of health and identity development likely diverged owing to distinctions in the social ecology of development. Because our focus is on narratives related to HIV/AIDS, health, and sexual culture, we emphasized the way in which each generation is positioned in relation to the AIDS epidemic. The oldest generation, which we refer to as the AIDS-1 Generation, consists of men born in the 1950s and 1960s and in their fifties at the time of our study. These men experienced childhood and early adolescence at a critical historical moment for sexual and gender identity minorities: the Stonewall Inn riots of 1969 (Carter, 2004). Men of this generation experienced adolescence and young adulthood in the 1970s, an era of community building for sexual minorities and social change in scientific and cultural attitudes toward homosexuality (e.g., the declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness in 1973; see Minton, 2001). They likely benefitted from heightened visibility and the growth of institutions and communities that facilitated social and sexual connections with other same-sex attracted men (see D’Emilio, 1983; Levine, 1979). However, men of this generation experienced significant losses with the emergence of the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and the cultural backlash that condemned homosexuality and the sexual minority community at large (Herek & Glunt, 1988).

Men of the AIDS-1 generation had experienced a sexual culture in early adulthood in which condomless sex with multiple partners was normative. They then experienced the radical shift in gay men’s sexual culture in the 1980s in which condoms and monogamy became key tools in the effort to prevent HIV transmission (e.g., Davidson, 1991). In their thirties, men of this generation witnessed the discovery of protease inhibitors in the mid-1990s as a breakthrough treatment approach for HIV that effectively transformed the meaning of HIV/AIDS from a lethal illness to a chronic, manageable condition (e.g., Rofes, 1998). By the time these men were at midlife (the 2000s), the sexual culture had shifted again to accommodate condomless sex with multiple partners, often with intentional risk reduction strategies such as serosorting (Adam, 2005, 2009; Dean, 2009). As these men approached their fifties in 2012, PrEP was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an effective form of prevention for HIV.

The middle generation, which we refer to as the AIDS-2 Generation, was born in the 1970s and early 1980s and were in their thirties and early forties at the time of our study. They experienced childhood and early adolescence during the height of the AIDS epidemic and were thus subject to considerable stigmatizing discourse and an equation of male homosexuality with disease and early death (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). The sexual culture into which many were socialized in the 1990s was one in which condoms and monogamy were privileged, and condomless, multi-partner sex was taboo. Men of this generation experienced shifts in gay male sexual culture in their twenties and witnessed the emergence of PrEP in their thirties.

The youngest generation, which we refer to as the Post-AIDS Generation, was born in the 1990s and were 18–25 years old at the time of our study. They experienced childhood and early adolescence with the dominant discourse of marriage equality and with a “post-AIDS” sexual culture in which HIV was no longer seen as a fatal illness. Unlike men of the two prior generations, they did not witness the immediate impact of AIDS and hence may have approached condomless sex with less concern about HIV. Men of this generation were in adolescence or early adulthood at the time PrEP was approved in 2012. Hence their entire experience of sexual culture has occurred at a time in which PrEP was available as a highly effective prevention tool and barebacking was seen as increasingly less taboo.

In sum, gay and bisexual men alive today are members of distinct generation-cohorts whose development likely diverges based on the history of gay men’s sexual culture over the past half-century (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). Men in their fifties initially experienced an open sexual culture of the 1970s which, prior to AIDS, was characterized by sex with multiple partners and did not mandate condom use. They then experienced the cultural trauma of AIDS and the radical shift in the meaning and practice of sex between men. Today they experience a new sexual culture that has benefitted from advances in prevention and treatment of HIV. Men in their thirties, by contrast, came to sexual maturity in an era of compulsory condom use and negativity toward multi-partner sex, having been socialized at a time when homosexuality and disease were closely linked. They now experience a more open sexual culture with the availability and adoption of PrEP. Men in late adolescence and young adulthood had little encounter with AIDS and thus experienced sexual maturity at a time when bareback sex had become more common and increasingly less stigmatized with the emergence of PrEP.

PrEP, Public Health, and Sexual Culture

Although research has demonstrated PrEP can be an effective HIV prevention tool when used correctly, narratives about PrEP and its impact on public health and sexual culture have not been universally positive. For example, the “Play Sure” campaign initiated on December 1, 2015 in New York City frames PrEP as a tool that can be used to enhance safety while also promoting sexual pleasure and intentionally avoiding any language of sexual stigma (see Figure 1). By contrast, the Los Angeles-based AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) initiated a campaign the same month called “PrEP: The Revolution that Didn’t Happen” (Figure 2). This campaign strikes a more negative tone, promoting the idea that PrEP has reduced safety by discouraging prior prevention methods. The campaign makes heavy use of sex-negative and stigmatizing language, as well as inaccurate information about the science behind PrEP and its effectiveness.

Figure 1.

Advertisement from New York City’s “Play Sure” campaign, December, 2015.

Figure 2.

Advertisement from Los Angeles’ AIDS Healthcare Foundation (AHF) campaign, “PrEP: The Revolution that Didn’t Happen,” December, 2015.

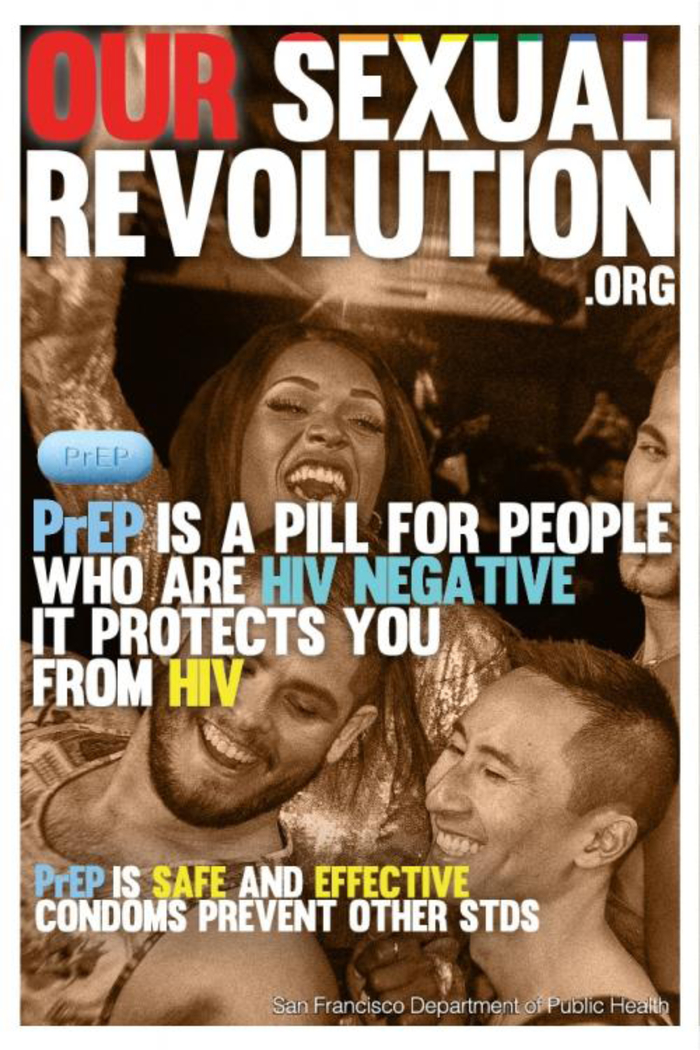

Narratives of PrEP have also framed its impact on sexual culture. For example, campaigns such as the “I Like to Party” video ad (released in November, 2015 by Public Health Solutions) suggest that PrEP has led to a more promiscuous, overly “casual” sexual culture and frames this shift as negative. Thus the emergence of PrEP is framed as having a negative impact on gay and bisexual men’s sexual culture by stigmatizing multi-partner sex and sex in general. By contrast, the “Our Sexual Revolution” campaign initiated in June, 2016, by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation depicts PrEP in a highly positive light for its impact on sexual culture, using the language of “sexual revolution” (Figure 3). The campaign alludes to the earlier period of sexual revolution and a more “queer” sexual culture of the pre-AIDS era in which heteronormative concepts like monogamy were directly challenged.

Figure 3.

Advertisement from the San Francisco AIDS Foundation’s “Our Sexual Revolution” campaign, June, 2016.

Schwartz and Grimm (2017) examined over 1,000 of the top tweets on Twitter about PrEP the year before it was officially endorsed by the CDC as a highly recommended prevention tool for gay and bisexual men who are HIV-negative and at substantial risk for HIV infection. They found that the majority of tweets (54%) could be classified as purely informational and focused on spreading awareness of PrEP. Tweets also discussed barriers to use of PrEP (15%) and consequences or limitations of PrEP (13%). They found evidence of perpetuation of the competing narratives of PrEP’s impact on public health and sexual culture, with 7% of tweets explicitly stigmatizing use of PrEP and 9% explicitly destigmatizing PrEP. These destigmatizing or “anti-stigma” tweets were the most likely to be selected as a “favorite” and to be re-tweeted.

The current context is one in which knowledge and awareness of PrEP is in a state of broad emergence within communities of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. While research suggests that knowledge and awareness of PrEP among gay and bisexual men is increasing over time (Mosley, Khaketla, Armstrong, Cui, & Sereda, 2018), many men are unaware of PrEP and its potential benefits for HIV prevention (Fallon, Park, Ogbue, Flynn, & German, 2017; Hoff et al., 2015; Merchant et al., 2016). Men who are aware of PrEP appear to get much of their information about it online, including websites, social media, and hookup apps where other men note PrEP use (Goedel, Halkitis, Greene, & Duncan, 2016; Merchant et al., 2016; Pérez-Figueroa, Kapadia, Barton, Eddy, & Halkitis, 2015).

Research on PrEP has revealed that many men are interested in or willing to use PrEP (Barash & Golden, 2010; Brooks et al., 2012; Goedel et al., 2016; Hoff et al., 2015; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Merchant et al., 2016; Oldenburg et al., 2016; Rendina, Whitfield, Grov, Starks, & Parsons, 2017), though the percentage of HIV-negative men on PrEP remains low (e.g., Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018; Klevens et al., 2018; Lachowsky et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2017; Strauss et al., 2017). In spite of willingness to use PrEP, many studies suggest that PrEP has not been widely adopted. For example, 78% of HIV-negative men in one recent study reported a willingness to use PrEP, but only 5% were actually doing so (Oldenburg et al., 2016). In a nationally representative sample of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men, only 4.1% reported PrEP use (Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018).

Recent research generally indicates a high degree of ambivalence about PrEP among men, with one recent study revealing almost equal numbers of men unwilling (42%) and willing (41%) to take PrEP (Rendina et al., 2017). In a survey of nearly 1,000 gay and bisexual men across the USA, Parsons and colleagues (2017) found that 53% of men who met the criteria established by the CDC were unwilling to take PrEP or did not believe they were appropriate candidates. Among a nationally representative sample of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men, 68.4% of those familiar with PrEP reported positive attitudes toward using it (Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018).

Many factors seem to play a role in heightened levels of willingness or interest in PrEP, especially if one is in a serodiscordant relationship (Brooks et al., 2012; Hoff et al., 2015; Kubicek et al., 2015; Kuhns, Hotton, Schneider, Garofalo, & Fujimoto, 2017). Lack of interest or unwillingness to use PrEP appears to be associated with concerns about side effects (Goedel et al., 2016; Mutchler et al., 2015), lack of knowledge (Goedel et al., 2016), perceived inaccessibility and unaffordability (Calabrese et al., 2016; Goedel et al., 2016; Hubach et al., 2017; Kubicek et al., 2015; Oldenburg et al., 2016; Pérez-Figueroa et al., 2015; Whitfield, John, Rendina, Grov, & Parsons, 2018), perceived stigma (Franks et al., 2018; Hubach et al., 2017; Kubicek et al., 2015; Mutchler et al., 2015; Pérez-Figueroa et al., 2015; Young, Flowers, & McDaid, 2016), and the perception that PrEP will lead to reduced condom use and greater sexual risk behavior (Eaton, Matthews et al., 2017; Grov, Rendina, Whitfield, Ventuneac, & Parsons, 2016; Hoff et al., 2015; Kubicek et al., 2015; Oldenburg et al., 2016; Pérez-Figueroa et al., 2015). Research has begun to document positive changes to sex and sexual culture some men on PrEP identify, such as more direct communication about HIV (Hannaford et al., 2018), reduced stigma against HIV-positive partners (Storholm, Volk, Marcus, Silverberg, & Satre, 2017), and reduced anxiety associated with sex (Brooks et al., 2012; Hojilla et al., 2016; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Storholm et al., 2017).

Some of the limited research conducted about men’s attitudes toward and use of PrEP suggests potential differences based on generation-cohort. For example, studies with younger men (approximately 18–25 years) suggest greater concerns about side effects than studies with a wider age range of men (e.g., Kubicek et al., 2015; Mutchler et al., 2015; Parsons, Rendina, Whitfield, & Grov, 2016). One study found that older men (over age 48) reported they would be more likely to stop using condoms if on PrEP, compared to younger men who reported they would maintain condom use (Hoff et al., 2015). Some studies suggest younger men may be more willing to take PrEP than older men (Barash & Golden, 2010; Kwakwa et al., 2016). Research that has examined differences across age cohorts suggests that PrEP use is low across cohorts but that familiarity is higher among men in the AIDS-2 generation than in either the AIDS-1 or post-AIDS generations (Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018). No studies to our knowledge have used qualitative methods in order to more closely interrogate cohort differences in attitudes or narrative accounts of PrEP.

Most gay and bisexual men appear to be in an active state of decision making about whether to use PrEP (e.g., Goedel et al., 2016; Grov et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2017; Rendina et al., 2017), and research must address the ways in which diverse groups of men engage with narratives about PrEP in this process. While men in urban centers may be receiving information about PrEP through targeted advertising campaigns or LGBT-oriented health centers (Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018), many men appear to be receiving information online (e.g., Pérez-Figueroa et al., 2015; Schwartz & Grimm, 2017). In order to tailor effective messaging to diverse communities of gay and bisexual men, research is needed to understand the way in which men are currently engaging with narratives of the meaning and effectiveness of PrEP for public health and sexual culture.

The Current Study

To examine variability in how gay and bisexual men are engaging with competing narratives of PrEP and its impact on public health and sexual culture, we interviewed men of distinct birth cohorts whose context of development diverged with regard to sexual culture and HIV/AIDS (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). Our aim was to examine similarities and differences in how men who were socialized in distinct historical eras and may be at differential risk for HIV interpreted the meaning and significance of PrEP, not only for their own health and sexual lives but also for the larger community. We sought to produce knowledge that could be beneficial to prevention efforts underway to dramatically reduce HIV infection among gay and bisexual men.

METHOD

Participants

Data for this study came from a larger qualitative study of identity, stress, and health among 191 lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the USA. The current study focused on the 89 participants who identified as men. A summary of participant demographics can be found in Table 1. Participants resided within 80 miles of one of four metropolitan areas: New York City (28%; n=25), San Francisco, CA (31%; n=28), Tuscon, AZ (22%; n=19), and Austin, TX (19%; n=17).

Table 1.

Interviewee Demographics.

| Generation-Cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-AIDS | AIDS-2 | AIDS-1 | Total | |

| Ages 18–25 | Ages 34–41 | Ages 52–59 | ||

| n=33 | n=31 | n=25 | N=89 | |

| Sexual Identity Label | ||||

| Gay | 27 | 22 | 22 | 70 |

| Bisexual | 4 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Queer | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Pansexual | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Two-spirit | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 5 | 7 | 9 | 21 |

| Black | 6 | 4 | 5 | 15 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 8 | 7 | 7 | 22 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 6 | 6 | 1 | 12 |

| American Indian | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| Bi/Multi-Racial | 5 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Education | ||||

| 6th-8th grade | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| High school | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Technical/trade | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Some college | 16 | 12 | 9 | 36 |

| Associates | 6 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Bachelors | 7 | 4 | 6 | 17 |

| Some postgraduate | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Completed postgraduate | 0 | 7 | 4 | 11 |

Participants were recruited from these four culturally and geographically diverse field sites using nonprobability sampling to reach a diverse sample of LGB people by identifying key venues frequented by sexual minority individuals (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008; Watters & Biernacki, 1989). Sampling venues were chosen to ensure a variety of cultural, political, ethnic, and sexual representation within targeted demographic groups. Venues included bars, non-bar commercial establishments (such as coffee shops and gyms), outdoor areas (such as parks), community organizations and groups (such as groups united by shared political, cultural, racial, and ethnic identities or interests), events (such as Gay Pride), online social media (such as Facebook and Instagram), and other online communities (such as newsletters and online publications). Recruitment caps were applied to each venue type to avoid the bias associated with recruiting all potential participants from one specific venue. The study intentionally avoided recruitment from venues that would over-represent individuals with mental health problems and/or stressful life events (e.g., health service providers, 12-step programs). Recruitment was conducted by sharing flyers with groups and organizations, sending emails, and posting information about the study online, and by reaching out in person by directly approaching potential participants at events and outdoor spaces to distribute study information.

Potential participants were directed to complete a brief demographic screening questionnaire, which took approximately 10 minutes. Potential participants were eligible for the study if they resided within 80 miles of New York City, Tucson, Austin, or San Francisco (in both urban and non-urban areas), if they identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (although they could use other terms, such as “queer,” “pansexual,” “two-spirit,” etc. to refer to their non-heterosexual identity), if their ages fell within the ranges we had previously identified for the three cohorts 1, if they resided in the USA between the ages of 6 and 13, if they were able to comfortably complete the interview in English, and if a spouse or partner had not already participated in an interview. In addition, enrollment quotas were used to target equal numbers of individuals from each age cohort from six racial/ethnic identity groups, including American Indian, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black or African American, Latinx, white, and bi/multi-racial. Participant selection at each site was also guided by an attempt to hear from individuals who had completed different levels of education in order to reflect the socioeconomic diversity of the population. Individuals who were determined eligible were contacted to schedule an interview.

Procedure

In-depth, semi-structured interviews lasting two to three hours on average were conducted to obtain narrative data on: life stories and critical life events, social identities and communities, sex and sexual cultures, minority stress experiences and processes, social and historical change for the LGBT community, healthcare utilization, and life goals. The current study focused specifically on male participants’ responses to questions in the protocol asking, “Do you see people in your community changing the ways they approach sex because of the availability of different medications for sexually transmitted infections or HIV? More specifically, how has the availability of PrEP, also known as the pre-exposure HIV drug, changed how people you know approach sex and relationships?”

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Los Angeles. Before starting the interview, we presented each participant with an informed consent form to sign, which was read aloud, explaining that participation was confidential and completely voluntary. Interviews were conducted by a trained team of interviewers in private meeting rooms in various locations, including university offices, LGBT community centers, and, occasionally, in participants’ homes and offices. Interviews were recorded on a digital audio-recorder and transcribed by professional transcribers. Participants received a $75 cash incentive, along with $5 to cover transportation costs to the interview site.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) in order to explore participants’ perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes about PrEP. An inductive, interpretive approach was utilized to identify and explain patterns of meaning within the data without pre-existing theories or hypotheses, although we were guided by an interest in how interviewees were appropriating or repudiating circulating narratives about the impact of PrEP on public health and sexual culture. Thematic analysis provides evidence for the meaning and complexity of social phenomena, thereby lending itself readily to public health practice (Green et al., 2007).

Data was managed and coded using the qualitative data analysis software Dedoose, version 7.0.23. Coding was conducted by two authors of the paper, one of whom was also one of the study’s principal interviewers. Coders were blind to the age cohort of each participant in order to minimize preconceptions about generational differences. Coding was supervised by three of the study’s principal investigators, who are the remaining authors of this paper.

Both coders conducted an initial round of open coding on all narrative data in order to familiarize themselves with the data, record memos, and generate a broad list of codes. Coders created categories to summarize the meaning described in each participant’s response, staying as close as possible to the participant’s own words. Codes were refined throughout the coding process by delineating distinct categories and merging repetitive categories when necessary. Codes were then organized to develop a codebook which included labels and descriptions for each code. Both coders used this codebook to independently conduct a second round of coding for each response, and then they met to compare codes and resolve inconsistencies in order to assign one set of codes to each response.

The two coders and principal investigators met regularly to establish a hermeneutic circle, or community of shared interpretive meaning (Josselson, 2004; Tappan, 1997), in order to discuss analyses and come to consensus on key themes based on patterns identified in the data. The principal investigators reviewed the coded data and helped to resolve inconsistencies and disagreements in coding. Tappan (1997) explains that with an interpretive approach, “interpretive agreement holds the only key to evaluating the ‘truth’ or ‘validity’ of any given interpretation of what a text means,” and that “the opportunity for insight and enlightenment is increased enormously when different voices and perspectives are joined in a common effort of understanding” (p. 653). That is, agreement within our interpretive community was strengthened by our different positionalities, which shaped our understanding and interpretation of the data. After coding was complete, themes were compared across age cohorts in order to explore generational similarities and differences. Themes are presented through data excerpts as evidence of our interpretation with attention to the range of responses. Frequencies were also calculated to assess patterns of difference across cohorts.

Reflexivity

The authors constitute a diverse group whose perspectives likely enhanced the analytic process. The first author is a cisgender, white gay man of the AIDS-2 generation who resides in the San Francisco Bay Area and has thus been heavily exposed to PrEP campaigns. The second author is a cisgender, white straight woman who served as the lead interviewer for the San Francisco Bay Area field site and is committed to bearing witness to gender, race, and class-based oppression. The third author is a cisgender, Black biracial lesbian and mother of two and stepmother to one, who has personally and professionally been involved in HIV/AIDS research and programs for 25 years. The fourth author is a genderfluid, Black queer femme of the post-AIDS generation who is a trained HIV test counselor and as such has a profound investment in HIV prevention. The fifth author is a cisgender, white gay man of the AIDS-2 generation whose research and teaching focus on sexual and gender minority lives, including relationships, sexuality, sexual risk, and HIV.

RESULTS

Attitudes toward PrEP

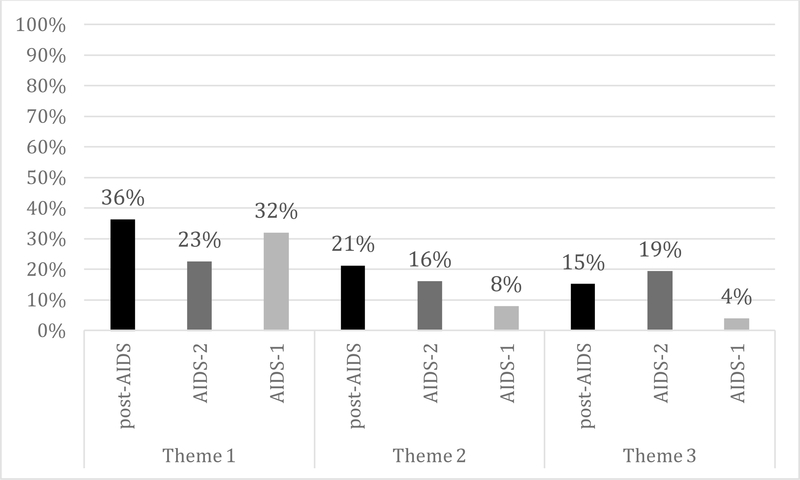

Participants’ overall attitudes toward PrEP were categorized as positive, negative, or ambivalent based on their responses to how PrEP has changed the way in which people in their community conceptualize and approach sex and relationships. Roughly one-third (37%) of participants were not categorized due to unclear or insufficient information. For those who could be categorized, participants’ attitudes organized by valence and age cohort are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Participants’ attitudes toward PrEP by valence and birth cohort.

Attitudes were similar across the post-AIDS (younger) and AIDS-1 (older) cohort, with over half holding positive views (55% and 53%, respectively), about one-third holding ambivalent views (36% and 40%, respectively), and very few holding negative views (9% and 7%, respectively). In contrast to their peers in the post-AIDS and AIDS-1 cohorts, only about one-third (32%) of men in the AIDS-2 (middle) cohort held positive attitudes toward PrEP, while a much greater proportion were ambivalent (47%) or negative (21%).

Narratives about PrEP

Our analysis was guided by our conceptual interest in how men engaged with cultural narratives about PrEP and its impact on both public health and sexual culture. This approach was anchored in narrative engagement theory in social psychology, which posits that individuals appropriate or repudiate narrative content to match their sense of identity and position their group in a positive light (e.g., Hammack & Toolis, 2016). Beyond simply categorizing narratives as “positive” or “negative” with regard to their stance on PrEP, we sought to identify the meaning participants were actively making of PrEP and its impact. Our qualitative approach allowed us to go beyond valence, then, to interrogate meaning making so as to inform public health approaches to promote PrEP.

Using inductive thematic analysis, we identified three overarching themes present in participants’ narratives about PrEP: (1) PrEP has had a positive impact on public health by effectively preventing the transmission of HIV/AIDS; (2) PrEP has had a positive impact on gay men’s sexual culture by reducing anxiety and making sex more comfortable and enjoyable; and (3) PrEP has had a negative impact on public health and sexual culture by increasing condomless, multi-partner sex. To examine generational similarities and differences, we tabulated frequencies of both thematic reference (i.e., participants mentioning the theme, revealing their familiarity with it in the broader discourse) and endorsement (i.e., participants clearly stating their appropriation of the theme into their own personal narrative of PrEP). We present frequencies of thematic endorsement by cohort in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Participants’ endorsement of themes by cohort.

Theme 1: PrEP has had a positive impact on public health by effectively preventing the transmission of HIV/AIDS.

Participants’ responses to questions about PrEP indicated that many thought about the intervention in terms of its positive impact on public health. Across the three cohorts of men, many participants discussed the positive implications that PrEP has had for public health, characterizing the advent of PrEP as a symbol of progress and an effective tool in enhancing protection against HIV. Participants in the younger (post-AIDS) and older (AIDS-1) cohorts were the most likely to endorse this narrative, whereas participants in the middle (AIDS-2) cohort demonstrated more ambivalence regarding PrEP’s impact on public health.

Among participants in the post-AIDS cohort (ages 18–25), 58% referenced the narrative that PrEP enhances safety and helps to prevent HIV/AIDS, and 36% endorsed this narrative. For many participants in this cohort, PrEP was perceived as a signal of progress and hope for the future. Max, a 20-year-old Asian American gay man, narrated:

I definitely see a lot more people use it [PrEP] now, which is great. A lot of people are more—very protective. Most of the time when I see people who are HIV positive, they’re always the older generation. I used to do the AIDS Walk every year and I discover—I seen the growing change of people wanting to be more protected now.

Max’s narrative positions PrEP as part of the larger history of AIDS for gay men, viewing PrEP as a step toward greater protection for gay men’s health.

The use of PrEP was perceived by many in the post-AIDS generation as a reflection of the care that young people in the LGBT community take to educate and protect themselves. For example, Matt, a 24-year-old American Indian and Latino queer man, described PrEP as an important step forward:

I’ve seen a lot more people get on PrEP, thankfully, especially here in Tucson. A lot of them were addicts, so they have a lot of unprotected sex. Hey, they’re on PrEP. That’s something. That’s great. The fact that they’re even thinking about this is huge to me. I’ve also had a lot of my undocuqueer friends ask me about it—like what insurance pays for and stuff like that. …It makes me so happy this thing is available. That just makes me happy.

Similarly, Josh, a 23-year-old American Indian gay man, perceived PrEP as expanding the options to protect the community against HIV:

There’s also that other assurance of if you use condoms and you use PrEP then you have a smaller chance of contracting HIV… I think it’s pretty cool now that there’s options. There’s a lot of options now than there were a couple years ago.

Narratives of men of the post-AIDS generation such as Josh, Matt, and Max revealed the optimism members of this generation have with the availability of PrEP.

Optimism regarding PrEP was apparent in many of the responses from men of the AIDS-1 generation (ages 52–59) as well: 56% referenced the narrative that PrEP has had a positive impact on public health, and 32% endorsed the narrative, demonstrating that many men in the older cohort support the view that PrEP is effective and signals progress. Cyril, a 53-year-old Black and Native American bisexual man, expressed his excitement about PrEP and faith in its efficacy when talking about sexual behavior:

I’m glad that they have PrEP, because I believe people out there are still—people just keep having sex. Condoms don’t—it’s not a stop-all…for males at least. Sexual behavior’s gonna be around forever…. I’m glad that we have PrEP. I’m glad that it does work… I’m feeling very encouraged by PrEP.

Cyril’s narrative reveals enthusiasm for the availability of PrEP, and he recognizes its effectiveness to prevent HIV.

Like Cyril, Ron, a 55-year-old Black gay man, also endorsed the narrative that PrEP is an effective HIV prevention tool. Ron described approaching his doctor to request a prescription for PrEP, communicating his trust in the medication to offer protection from HIV transmission:

PrEP is effective even if you only take it three or four times a week. It’s still more effective if you take it daily. If you take it three or four times a week, it’s still effective… If I’m on PrEP and [my partner] is undetectable, we don’t need to use a condom. I’ve had this conversation with my doctor. He’s like, “It’s virtually impossible for you to become HIV positive if you’re using PrEP correctly and he’s undetectable.”

The narratives of men such as Cyril and Ron reflect a positive view of PrEP’s potential impact on public health from members of the older generation. In fact, many interviewees who are members of the AIDS-1 generation advocated for increased availability and awareness of PrEP. The narrative of Martin, a 57-year-old Black gay man, illustrates:

I actually did the [Truvada] trials. I do a lot of studies and trials that would help people with HIV and/or AIDS. I did the first [Truvada] trial my damn self. The thing that really gets me is number one, PrEP and [PEP2], both can help sexually—men, active, keep from getting HIV. Talk to the guy out there, he doesn’t even know what you’re talking about. This is in San Francisco. Like I said, as far as we’ve come, we could go a bit further. For me, I never worry about that, because I’m super safe. If I ever did slip, I’d run and get one of those pills real quick.

Martin identifies PrEP as a valuable tool to protect against HIV, and he suggests that more needs to be done to inform men about its value. Hector, a 58-year-old gay Latino man, also endorsed the narrative that PrEP has the potential to make a positive impact on public health and expressed the desire for it to be more available, saying, “I’m all for it because there’s still risky behavior going on… I think that, yeah, if a person should have something available that could help them, like, I think Truvada is being used.”

Compared to men in the younger (post-AIDS) and older (AIDS-1) cohorts, participants in the AIDS-2 cohort (ages 34–41) less frequently endorsed the view that PrEP has had a positive impact on public health by reducing the transmission of HIV, with 65% referencing and 23% endorsing this theme. Some members of the AIDS-2 generation who did endorse this theme shared that they or their partner were using PrEP and were thankful for the protection it provided. For example, Rob, a 36-year-old American Indian two-spirit man and self-described user of PrEP with an HIV-positive partner, explained, “You can’t get the virus if the virus tries to attach… Dating somebody positive—I don’t know, it’s just a big thing for me now.” Another participant in the middle cohort, Jeremy, a 34-year-old bisexual, multiracial man, shared a desire to use PrEP:

I would love to have that… It would be nice if that was a drug that they just gave away, and I know that I’m gonna get that as soon as I’m able to… I’ve told people about PrEP and Truvada, and I read reports about them, and they sound like amazing drugs.

Other participants in the middle cohort referenced PrEP’s potential positive impact for public health but demonstrated ambivalence in their responses. Kevin, a 36-year-old white gay man, endorsed the idea that PrEP has had a positive impact on public health but expressed some reservations:

I think if it’s gonna help as a pre-exposure thing, I think it’s wonderful. I think that’s great… I stand behind it, because being a person who’s been positive as long as I have and almost dying, it really—it really shows we’re coming a long way medically. I do think some people place judgment upon it… Well, I heard that it’s—why give a person HIV meds who is not HIV positive? Which I understand that aspect of it. I’m on both sides of the coin, even-wise. …I think in some ways it’s good, and I think some ways, health-wise, there’s concerns for that aspect as far as the liver aspect is concerned… Then there’s the part where you could be pre-exposure to save lives. There’s two sides of that coin.

Although Kevin shares enthusiasm about the potential for PrEP to save lives, he notes that there are “two sides of that coin” due to potentially harmful side effects.

In addition to participants who endorsed the view that PrEP enhances protection against HIV, others referenced this narrative as a way to discredit PrEP’s positive impact on public health. For example, Gabriel, a 35-year-old Latino gay man, narrated:

They’re bigger whores now because they’re on PrEP, because they think they can’t get shit. Basically, you can still get STD or HIV still being on PrEP, I think. Because there’s still that risk. I think more people think they’re not at risk, because, “Oh, I’m on PrEP.” I’ve heard people praise about this thing, this new drug. I think more people are more whores on it. They’re not using condoms or anything else with it, because they’re on PrEP. They think they’re untouchable. That’s the way it is. They think they have this bubble from not getting anything. That’s why I think more and more people are getting on it.

Gabriel acknowledges that he is aware of the circulating discourse that PrEP offers protection against HIV, but he disavows this narrative, expressing the belief that PrEP actually contributes to risky sexual behavior.

Theme 2: PrEP has had a positive effect on sexual culture by making sex more comfortable, enjoyable, and less characterized by anxiety.

Many men in the post-AIDS and AIDS-2 generations perceived PrEP as contributing to a more positive sexual culture by increasing comfort and reducing worry about HIV. The theme that PrEP has had a positive impact on sexual culture was the least prevalent among men in the AIDS-1 cohort. Twenty-eight percent of men in the AIDS-1 cohort referenced this theme, and 8% endorsed it. Among men in the AIDS-2 generation, the narrative that PrEP has had a positive effect on sexual culture was referenced by 32% and endorsed by 16%. For those in the post-AIDS generation, this narrative was referenced by 39% and endorsed by 21%.

The narrative that PrEP has had a positive effect on sexual culture by reducing anxiety and increasing comfort with sex was most pronounced among members of the younger (post-AIDS) cohort. For example, Chris, a 22-year-old Middle Eastern and multiracial gay man, explained:

…With PrEP, it’s a big relief for people before they have sex. I think a lot of the worry is that you have to wait after sex, or, when you’re having a test, it needs to be always in a certain time frame. Then, when you wanna do another test, there needs to be a gap in order to see if you’re positive for something. I think having PrEP, it just negates all that. You could just have protection. Go into sex feeling secure and safe rather than going into sex being worried, and then worrying afterwards. I think just feeling relieved going into sex makes it more pleasurable.

Jordan, a 23-year-old white gay man, echoed this sentiment and observed that since starting to take PrEP several months before the interview, “I think PrEP will make it a little bit safer, and I’ll feel more secure knowing that that’s there… I’m a little more confident now.” Here, Jordan is not only indicating the significance of health risk reduction, but also the ways that health risk reduction reduces anxiety and improves comfort with sexual practices.

Some participants also connected the availability of PrEP to an increased willingness to engage in sexual activity. Nick, a 22-year-old Asian American gay man, explained:

It’s definitely a big impact, because I think people would be more—I guess, I don’t know, more willing to have sex with a stranger, say, than before, because they’re more protected. If you were to do that and practice safe sex at the same time, there’s even lower risk and lower chances of you getting anything. For those that are paranoid before can be more comfortable… I feel like if I did go on PrEP, I too would be a little bit more—I would be more willing to have sex with a stranger, like if I just met them…

By reducing barriers to engaging in sexual activity and reducing the fear of contracting HIV, PrEP was perceived by many younger participants as contributing to a more open, free, accessible, and enjoyable sexual culture.

When asked if the availability of medications such as PrEP have changed the way people approach and talk about sex, Adrian, a 24-year-old Latino gay man, replied:

Definitely. [I] just think that it’s kind of changing status conversation a lot… because you don’t have a certain status… There’s not just negative and positive anymore. It can’t just be a tea party of negative people talking about this person’s positive and this person’s positive. Because now, you have guys at the tea party that’re on PrEP or that have been undetectable for five years. It’s like the definition of HIV status is kind of changing.

Adrian views PrEP as radically shifting the meaning of serostatus for gay and bisexual men, away from a simple binary (negative/positive) toward greater complexity (e.g., on PrEP, positive but undetectable, etc.) that can inform a risk reduction strategy in sex. Adrian views this shift as reducing the stigma once associated with HIV/AIDS.

Similarly, Ryan, a 21-year-old white gay man, narrated, “I think AIDS has been destigmatized… It’s affording more options. Yeah. I think it doesn’t—I think it doesn’t exile things as much, HIV.” Josh, a 23-year-old American Indian gay man, observed,

There’s a lot of options now than there were a couple years ago. There’s still that stigmatization of even being near somebody who has AIDS…but it’s—I think in a couple more years it probably won’t be such a big deal.

Men such as Ryan and Josh see the endurance of stigma, but they associate the introduction of PrEP as a turning point in the larger narrative of AIDS stigma. With its positive impact on the sexual culture of gay and bisexual men, PrEP plays a role in the gradual decline of AIDS stigma.

Although endorsed less frequently than among men of the post-AIDS generation, PrEP was welcomed by some AIDS-2 generation participants as a way to experience intimacy and freedom from the terror of AIDS. Rob, a 36-year-old American Indian two-spirit man who uses PrEP, went so far as to call PrEP “a revolution.” He elaborated:

I think that we’ve spent so much of our adult lives, sexual adult lives, with that fear ingrained in your head that you’re going to die of HIV and AIDS, and now there’s this pill and this drug that you take that blocks it, doesn’t happen. Yeah, it’s a revolution. It’s changing people’s mentality, so people have—with my friends, they have the mentality, “Well, I’ve wasted my whole life worrying about it, and now I don’t have to,” so they want to be free.

Like Rob, James, a 41-year-old Asian American queer man, also saw the ability to have condomless sex allowed by PrEP as exciting and liberating:

I would say at least the last five years there’s been a whole culture of “barebacking”—sex without condoms. Things like that be super, super sexually desirable. Why that is—I would have to say I think it’s maybe because it’s generations of people who grew up—they were taught that sex was this fearful thing. You were gonna get something. I don’t know. Maybe there’s something really liberating about not doing that. I can say, speaking as someone in a relationship with my partner, we don’t have sex with condoms anymore, and there is something super awesome about that because, growing up only with that, it means something different now. Yeah, so that is something that’s definitely changed in terms of the way people, at least in the male communities, have sex, for sure.

For Mike, a 37-year-old Latino gay man, and Mike’s community, PrEP also represented the opportunity to have condomless sex. Mike linked PrEP to freedom from worry about HIV:

I used to be worried about HIV and AIDS, but now it feels—preliminarily speaking, with the whole PrEP thing and Truvada, that so far, so good. I mean it’s not a cure-all, but the signs are pretty affirmative. …Every one of my friends is on PrEP and is not using protection, so yeah… People are going like “Oh, it’s not a death sentence anymore. Like, pop this pill. I can go bareback whoever I want to.” That is an adjustment for my mind because for so long we’ve been like, “Wear a condom, protect yourself.” It’s been drilled and so now it feels very like oh, my gosh, what? Oh, really? I haven’t experienced that… Yeah, you could get another STD and that’s not a good thing, but it sounds like for the most part, we have remedies for those.

Although Mike acknowledges that the thought of having sex without condoms is “an adjustment” and that PrEP does not protect against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), his overall perception is positive, and he views PrEP as central to a new sexual culture in which men no longer associate sex with death.

Theme 3: PrEP has had a negative impact on public health and sexual culture by increasing condomless, multi-partner sex.

Although many participants endorsed the narrative that PrEP enhances safety with regard to health risks and contributes to a sexual culture characterized by less anxiety and greater pleasure, others worried that PrEP has had a negative impact on public health and sexual culture by increasing condomless, multi-partner sex. This theme was commonly referenced across age cohorts (42% in the post-AIDS cohort, 55% in the AIDS-2 cohort, and 40% in the AIDS-1 cohort), and endorsed most frequently by men in the post-AIDS cohorts and AIDS-2 cohorts (15% in the post-AIDS cohort, 19% in the AIDS-2 cohort, and 4% in the AIDS-1 cohort).

Across all three generations, many men feared that PrEP decreases condom use, which was perceived as unsafe and risky. For many participants, these reservations were rooted in a concern that PrEP is “not 100%” effective and thus should not be used without condoms. The narrative of Shawn, a 21-year-old Black gay man, illustrates this view:

I feel like people are gonna be more sexually active once that’s more known about, the PrEP thing, that medication. Cuz it prevents—it’s supposed to prevent HIV, AIDS and STIs, but I can’t believe that 100% from just takin’ a pill. You still gotta be safe.

Shawn’s narrative reveals concern that PrEP use may be associated with greater sexual activity and may provide those who take it with a false sense of confidence in protection. He implies that a PrEP-only protection strategy may, in fact, not be considered “safe” and questions the effectiveness of PrEP to even prevent HIV transmission.

Uncertainty about the effectiveness of PrEP to prevent HIV was shared by men in the AIDS-1 cohort. Ken, a 59-year-old Latino gay man, noted, “Some people are saying it gives people a false sense of security cuz it’s not 100 percent foolproof if you take PrEP that you’re not gonna get infected.” When asked how he felt about this narrative, Ken went on to say,

I’m 50/50. [Laughter] At first I was always tended to not think that it was such a good idea, because again it was gonna get people that false sense of security. On the other hand, now and actually I met a few––in a few of these HIV conference and things, I met some guys from Austin that actually who started a PrEP clinic in Austin. To hear their viewpoint and they’re my age range and they migrated to Austin from other cities. Bigger cities up east and stuff. They have that experience like I do. Again if they can still even as much as save as one person from getting infected it’s worth it. Because again you can’t say that anything you do is gonna be foolproof. I don’t necessarily think––you’re not gonna stop that behavior. Young kids are gonna be young kids. I don’t care if you’re in San Francisco or San Antonio if they’re gonna party and drink and do drugs and have sex they’re gonna do that regardless. At least there’s another alternative besides condoms that they can go to. There’s more scientific data with PrEP.

In his narrative, Ken expresses conflictual feelings about the effectiveness of PrEP, repeatedly referring to it as “not foolproof” in its ability to prevent HIV. Yet, Ken also demonstrates openness to this view being challenged, as when he described his experience getting more information from experts. Ken’s narrative ends with a statement of the positive potential of PrEP, as he recognizes the value of “another alternative besides condoms” to prevent HIV.

A second perceived risk to public health posed by PrEP was the concern that PrEP does not protect users against non-HIV STIs. This fear was voiced by Brad, a 40-year-old white gay man, who stated, “My problem is, is that, one, nothing is 100% and, two, PrEP is only supposed to protect you against HIV. There’s a plethora of other things that you can get out there.” A member of the older cohort, Greg, a 52-year-old Black gay man, echoed concerns about PrEP’s limitations in enhancing safety:

Just because you’re on PrEP doesn’t necessarily mean that you shouldn’t still practice safe sex, that you shouldn’t be concerned about all the other sexually transmitted diseases and its impact on everybody, especially that person that you’re going to be with.

As Greg’s narrative illustrates, many men across generations appeared to place Truvada and its use outside the frame of “safe sex,” both because they associate it with condomless, multi-partner sex and because they are skeptical of its effectiveness.

A third component of this theme was that PrEP has contributed to a more open and carefree sexual culture, resulting in sexual behavior that some interviewees framed as “irresponsible.” This theme was articulated by men across age cohorts, including a number of younger men. For example, Scott, a 23-year-old white gay man, stated:

It almost seems like PrEP is encouraging unsafe sexual behavior to some degree amongst certain communities, in that if you go on Craigslist or Grindr or what have you, sometimes it’s mentioned for people who are interested in sex without condoms or protection as an encouragement to have that type of sexual interaction… It has been a benefit that it’s another option, but it seems like it’s encouraging negative behavior that’s riskier.

Corey, a 24-year-old American Indian and white bisexual man, also expressed doubts about PrEP’s positive impact:

I’m not sure of how good an effect it’s had. Well, I know that there’s a lot of people who are like basically just having a bunch of what’s called “bareback” sex, condomless sex now because they’re on PrEP. They think that that’ll prevent them from getting HIV. I know a lot of that is happening. It’s like, I mean, I’m not gonna condemn those people, but it’s like, “Y’all, just because you’re on PrEP doesn’t mean you have a bunch of bareback sex with people that are on HIV.” I feel that it’s definitely caused a little bit of risky behavior, but I’m sure it’s probably done good. I’m not downing it or anything. It’s just from what I’ve seen is that there’s a lot more people that are willing to risk that behavior.

Men like Scott and Corey expressed concern that the emergence of PrEP has created a new sexual culture that promotes multi-partner sex without condoms—a shift that he and others see as potentially dangerous for gay and bisexual men.

Some men distanced themselves from this dominant conception, such as Alex, a 20-year-old Latino gay man, who stated, “I’m not on PrEP. I’m thinking about getting on it, not because I can go crazy barebacking, but because I wanna protect myself and be safe.” He went on to explore differing dominant narratives, contrasting those that link PrEP to a safer and more open sexual culture and those that link PrEP to a more negative, promiscuous sexual culture:

With the whole PrEP thing that was the problem with being a “PrEP whore.” Then which went from a positive approach where everyone should be on PrEP for safety and to protect themselves and their partners and whoever they have sex with went to a new term to be created with “PrEP whore.” Everyone was now in two deciding teams of pro-PrEP and con-PrEP. It was a huge mess, you could see it in the apps, it was all over. “All PrEP whores, stay away.” “On PrEP, ready to bareback, breed me. Give me your seed.” All kinds of shit. It was just alarming. Cuz I was just like, “Wow.” This medicine which was supposed to benefit us is now being questioned.

Alex’s narrative reveals the extent to which many gay and bisexual men are actively navigating competing narratives of the meaning of PrEP and engaging with discourse about sex and sexual practices that is contested.

The perception that PrEP promotes irresponsible sexual behavior was most prevalent among men in the AIDS-2 cohort. On the whole, the narratives of AIDS-2 generation participants were marked by skepticism and even cynicism about PrEP. Nathan, a 38-year-old Black gay man, shared the following pessimistic view about PrEP:

We all think PrEP is just an open challenge… That’s like getting folks carte blanche to play around…. It’s a good thing, but it’s a double-edged sword to it because you givin’ people a way to have bareback sex… PrEP ain’t gonna help—PrEP gonna help some, but it ain’t gonna help others because at the end of the day, you’re just givin’ people carte blanche to go fuckwall. It’s a guarantee. You talkin’ ‘bout somebody might be takin’ five—you tellin’ me PrEP gonna work for that person who’s takin’ five, six different types of nuts inside them in one day? You think it’s gonna really work really well? That’s gonna be a problem.

Nathan expresses skepticism that PrEP will be effective for highly sexually active men, and he frames PrEP as creating a sexual culture that he sees as a “problem.”

For Nathan and other members of the AIDS-2 generation, who came of age during the height of the AIDS epidemic and had the importance of condoms “drilled into them,” many perceived PrEP as causing a frightening resurgence in “bareback” or condomless sex. Discourse by men of the AIDS-2 generation was marked by a language of fear and worry, and they struggled to equate anything other than condoms with safety, thus perceiving sex with PrEP alone as “unprotected” and dangerous. Lawrence, a 40-year-old American Indian gay man, narrated:

Well, they think they don’t need to use condoms no more. That’s what scares me. [Laughter] I mean, they’re like, “Well, I’m taking Truvada, so I’m good to go.” I’m like, “Mmm. No. I’m okay.” They think if they’re taking the PrEP, and the other person’s on meds? That, “Okay. It’ll work.” Maybe, but who’s gonna take that risk? I don’t wanna take that risk.

Narratives such as Lawrence’s reveal the extent to which many men are unaware of the nature of risk based on factors such as viral load for HIV-positive partners and the effectiveness of PrEP for HIV-negative partners. Their fear associated with any form of risk protection other than condoms reveals the extent to which they have internalized a “condoms-only” approach to safe sex.

Men of the AIDS-2 generation often framed PrEP use as only acceptable in combination with condoms, further revealing the significance of condom use in their sexual subjectivities. Victor, a 38-year-old Latino gay man, framed the abandonment of condoms among men on PrEP as problematic:

I’m not a fan of it. I think it’s a great additive to using—to be more secure of not getting an STD…and HIV. But I worry that that’s what people are doing. They’re using it just to not have to use condoms whatsoever, and not even worry about the dangers of STDs or anything like that.

Victor went on to share feelings of caution in embracing PrEP, expressing doubt in its efficacy and fear of abandoning the safety that condoms have long symbolized:

I do worry about the younger generation, and having more accessibility to these drugs because it’s—to me, it’s almost as an escape of, “Well, I had unprotected sex. I’ll just go and get checked and whatever happens, I’ll—I’m on PrEP…” It’s just I feel like there’s a lot of easy way outs. If that makes sense. I just feel like—I guess I’m just the old-school mentality where it’s just very, “Use a condom.” To me, that’s always been just my way of feeling that safeness. Maybe it’s a safety net or something, but I just feel like the younger generation is very much into the feeling-good aspect of it all, so they don’t use condoms. They wanna use these PrEP and everything that isn’t necessarily a hundred percent sure, but at the same time it’s kinda like it is good, but sometimes without any—you don’t know. It just scares me that it’s just gonna be another epidemic.

Some men of the AIDS-1 generation also shared a hesitance regarding PrEP and, rather than framing PrEP as a risk reduction tool, framed PrEP as associated with increased sexual risk behavior. While men of the AIDS-2 generation emphasized the significance of condom use in their narratives, men of the AIDS-1 generation often called upon their personal experiences with loss during the AIDS epidemic. The narrative of Greg, a 52-year-old Black gay man, illustrates:

That conversation about sexual responsibility isn’t happening as much. Now with PrEP, it’s like, “Oh, okay. I’m on PrEP. It’s like all things are—” for somebody who lived through and had many close friends die of HIV, AIDS, and complications of it, and for me, it’s like, “Wow.” While I welcome the advances in science, it’s just almost we’re using it as the excuse to be able to say, “Okay. I don’t need to worry about it anymore.” That’s not what we’re saying.

The older generation’s wariness reflected a collective historical trauma of surviving the AIDS epidemic. “Most of them will never in their lifetime have to bury a friend because they died of HIV, because of the advances of science,” observed Greg. “My friends, because they’re older, tend to have a much more sobering conversation about sex than some of the people that I talk to who are much younger.”

Randall, a 56-year-old white gay man, attributed a diminished responsibility and awareness of the danger of HIV/AIDS to the younger generation.

Look at the news, you never hear about HIV hardly ever. …The young people, they don’t have friends who’ve died from AIDS probably. Maybe some have. I don’t know. Family members, whomever. I think a large amount of them haven’t. They don’t know. They didn’t grow up during that time period.

This discussion of intergenerational tension was characteristic of narratives of men in the AIDS-1 generation. Men such as Randall spoke of the lack of experience younger men have with AIDS, which they frame as problematic for the sexual culture that has emerged post-PrEP.

Some men of the AIDS-1 generation acknowledged that their negative reaction to the sexual culture they saw PrEP facilitating was rooted in shock or disbelief that something as effective as PrEP may exist. Luis, a 55-year-old Latino gay man, narrated his process from initial shock to gradual recognition that PrEP may represent an effective prevention tool:

Oh my God, that blew my mind. I’m much softer about it [PrEP use] now because over the past year I’ve seen the studies. I see you become undetectable. You can’t give the virus, so that’s why you can have unprotected sex. It protects the person who’s negative. I’m not doing it, but I get it now. At first it horrified me, because it was just 180 degrees—not 360. It was 180 degrees from my thinking, right? My survival. My whole life. I’m still using condoms and all that with no problem, but whoa, what a change.

Luis acknowledged that his initial judgment that PrEP may be a negative for gay and bisexual men’s sexual health and culture has changed over time, as he has acquired new information. He narrated a personal journey in which he recognized the radical shift in thinking that has been required for men who lived through the AIDS epidemic.

DISCUSSION

Since its introduction as an HIV-prevention tool, PrEP has sparked international debate among gay and bisexual men. Perspectives on PrEP represented in the mainstream and queer media are often framed in one-sided and black-and-white terms, as either in favor of or against PrEP (Shapiro, 2014). This study is the first to qualitatively examine gay and bisexual men’s perspectives on the role that PrEP has had in shaping their sexual cultures and perceived public health landscape.

Taking a life course perspective that emphasizes the significance of birth cohort in the shaping of sexual subjectivity (e.g., Hammack & Cohler, 2011), we were able to interrogate the meaning of PrEP across three generations of men, distinct in the sociohistorical contexts that have shaped their formative experiences of sex and sexuality in relation to HIV/AIDS (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). Following social psychological theories that emphasize individual meaning making and engagement with cultural narratives (e.g., Hammack & Toolis, 2016), we used inductive thematic analysis to query the appropriation or repudiation of particular narratives about PrEP circulating in contemporary discourse. Regardless of their birth cohort, the men in this study expressed a range of perspectives that did not mirror the binary “for or against” perspectives often discussed in the media. Instead, the men’s narratives collectively reflected a diversity of perspectives, which add much needed nuance to the limited knowledge base on meaning making of PrEP, thereby highlighting important and complex grey areas in how gay and bisexual men view the impact of PrEP on their lives and sexual cultures.

Analyses indicated that three major themes, characterized by varying degrees of positive and negative attributes and specific content related to meaning making in the domains of public health and sexual culture discourses, emerged when examining gay and bisexual men’s narratives about PrEP. The salience and endorsement of some of these themes were more common among some cohorts than others. Gay and bisexual men in the post-AIDS (younger) cohort were more likely to emphasize the role PrEP had or could have in contributing to a positive sexual culture characterized by less anxiety and greater pleasure, whereas men in the AIDS-1 (oldest) generation were more likely to emphasize the positive impacts PrEP could have on the public health landscape. Men in the AIDS-2 (middle) cohort expressed the most ambivalence and negative perspectives toward PrEP, including worry about how PrEP has or might increase condomless, multi-partner sex.

This study adds evidence to ongoing dialogues about challenges related to the implementation of PrEP as a biomedical HIV prevention intervention. PrEP is a highly effective new prevention tool endorsed by health authorities, but uptake and adherence rates are not where the field desires (e.g., Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018; Klevens et al., 2018; Parsons et al., 2017). Research on PrEP use and attitudes has increased exponentially, and studies are beginning to consider the role of birth cohort or generational differences in how PrEP is perceived (e.g., Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018). Men of distinct cohorts are positioned differently in relation to the AIDS epidemic, which likely shapes how they engage with competing narratives of PrEP and its impact on men’s health and sexual culture (Hammack, Frost et al., 2018). Our interviews revealed that men of the younger and older generations were the most positive toward PrEP and its impact on public health and sexual culture, while men of the middle generation were the most negative and ambivalent and also the most uncomfortable with the abandonment of condoms.

Our examination of generational differences yielded the significance of another important, yet often overlooked factor in the HIV biomedical intervention framework for prevention—the role of sexual culture. As scholars have noted, HIV—its causes, consequences and potential modes for prevention and treatment—is an inherently social and cultural phenomenon (Kippax, Holt, & Friedman, 2011; Wilson & Miller, 2003). The similarities and differences between generational cohorts of gay and bisexual men’s ways of understanding the significance and value of PrEP were deeply embedded in their understanding of its impact on sexual minority men’s sexual culture and their efforts to negotiate how changes to sexual culture may reduce or invoke stigmatization of gay men’s sexuality. We found that for some men in the study, the introduction of PrEP as a prevention tool promoted a more comfortable and less stigmatized sexual life, free of the anxiety associated with sex during the AIDS epidemic. Other men framed PrEP as contributing to what they framed as irresponsible sexual behavior. Whether viewed negatively or positively by gay and bisexual men, one of the significant implications of this finding is that it highlights challenges to promote PrEP uptake without attention to concerns over the shifts in the cultural and community dimensions to sexual life.

Our analysis suggested the way in which gay and bisexual men contend with legacies of sexual shame and discourses of male homosexuality as “contaminating” as they make meaning of PrEP in a new, post-AIDS sexual culture. Evidence of engagement with such discourses seemed apparent when men positioned strategies such as PrEP use without condoms as outside the boundaries of sexual “safety” and invoked the pejorative specter of the “PrEP whore” to stigmatize the role PrEP has played in the contemporary sexual culture. That such discourse was most commonly found in narratives of men of the AIDS-2 generation reveals the imprint of the experience of childhood and adolescence at the height of the AIDS epidemic for these men. Their sexual subjectivities formed at a time in which gay men were intrinsically associated with disease and a discourse thrived which placed blame for the epidemic on the open sexual culture of the pre-AIDS era (Herek & Glunt, 1988).

Existing research on PrEP suggests that many gay and bisexual men are in a process of active decision making about whether to use PrEP (e.g., Goedel et al., 2016; Grov et al., 2016; Parsons et al., 2017; Rendina et al., 2017). Our findings are important in this regard because they illustrate the complex ways in which men of different generations engage with narratives about PrEP. The way in which men appropriate or repudiate specific narratives about PrEP is likely key in the decision-making process about whether to use PrEP. Thus, the findings from the present study may prove useful to inform messaging to diverse communities of gay and bisexual men. They may also inform health providers about the complex concerns of gay and bisexual men, which will be useful as providers discuss the availability and appropriateness of PrEP for their gay and bisexual male patients.

An important contribution of the study concerns the nature of gay and bisexual men’s perspectives investigated through qualitative thematic analysis. Previous research on gay and bisexual men’s perspectives on PrEP has focused on their personal knowledge/awareness of PrEP (e.g., Fallon et al., 2017; Hammack, Meyer et al., 2018; Hoff et al., 2015; Merchant et al., 2016) and interest/willingness to take PrEP (Barash & Golden, 2010; Brooks et al., 2012; Goedel et al., 2016; Hoff et al., 2015; Kwakwa et al., 2016; Merchant et al., 2016; Oldenburg et al., 2016; Rendina et al., 2017). Our findings complement this work by focusing on gay and bisexual men’s perspectives on how PrEP has impacted their communities, sexual cultures, and public health in general. Knowledge of men’s perspectives is vital in order to promote PrEP in communities of gay and bisexual men at elevated risk for HIV.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The findings of the present study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The data analyzed for this study were part of a larger study of generational differences in the experience of sexual identity, minority stress, health and health care access. Since PrEP was not the central focus of the study, the interview only addressed PrEP in a brief manner. In addition, the way in which our questions about PrEP were structured (e.g., “Do you see people in your community changing the ways they approach sex because of the availability of different medications for sexually transmitted infections or HIV?”) may have primed participants to construct narratives of change. Future research focused on gay and bisexual men’s perspectives on the impact of PrEP on public health and sexual cultures should implement more open-ended, nuanced, and varied questions designed to further explore the complexities of these issues.

Additionally, we did not collect information on the HIV statuses or sexual practices of the men in the study. For these reasons, we are not able to tell whether men in the study would be eligible and appropriate candidates for PrEP on an individual level. However, our interest was in how men viewed PrEP in the community, rather than with regard to their own personal behavior. Perspectives on the impact of PrEP may, however, differ depending on whether men are appropriate candidates for PrEP and/or are currently using PrEP.

Apart from the focus on generational differences, the present study did not examine other forms of individual or demographic differences in perspectives on the impact of PrEP. Future research should examine such factors as they may be helpful in understanding the lack of access, education, and uptake in specific subpopulations of gay and bisexual men. For example, research has revealed racial differences in PrEP attitudes and use. Some studies suggest that African American men may be less aware and less likely to take PrEP compared with white gay and bisexual men (e.g., Eaton, Kalichman, et al., 2017; Eaton, Matthews, et al., 2017; Kuhns et al., 2017). Other studies suggest high levels of interest and strong levels of openness to taking PrEP among African American men (e.g., Kwakwa et al., 2016; Merchant et al., 2016). African American men report distrust and suspicion of some sources of government-sponsored scientific authority, which may reduce their willingness to take PrEP (Cahill et al., 2017; Eaton, Matthews, et al., 2017). Given these findings, future studies with foci similar to those of the present study may be helpful in understanding the nuances underlying African American men’s perspectives on PrEP.

Conclusion

Ours is the first study to our knowledge to use qualitative methods to examine generational differences in perceptions of PrEP and its impact on public health and sexual culture. This approach allows us to examine the way in which men are engaging with competing narratives of PrEP as it is being heavily promoted in communities of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. Our findings illustrate the complexity of narrative engagement about PrEP and interrupt binary thinking about the meaning and value of PrEP. Men narrated nuanced accounts of PrEP across generations, while a pattern emerged in which men of the youngest and oldest cohorts had the most consistently favorable views of PrEP. Older men appear to frame the positive role of PrEP in terms of its impact on public health, whereas younger men focus more on the positive impact of PrEP on sexual comfort and intimacy. Thus public health approaches to PrEP promotion may benefit from unique tailoring to men of these different generations, variably appealing to public health or to sexual culture depending on the age of the target audience.