Abstract

Background

People with non‐cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis commonly experience chronic cough and sputum production, features that may be associated with progressive decline in clinical and functional status. Airway clearance techniques (ACTs) are often prescribed to facilitate expectoration of sputum from the lungs, but the efficacy of these techniques in a stable clinical state or during an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis is unclear.

Objectives

Primary: to determine effects of ACTs on rates of acute exacerbation, incidence of hospitalisation and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) in individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis.

Secondary: to determine whether:

• ACTs are safe for individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis; and

• ACTs have beneficial effects on physiology and symptoms in individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials from inception to November 2015 and PEDro in March 2015, and we handsearched relevant journals.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled parallel and cross‐over trials that compared an ACT versus no treatment, sham ACT or directed coughing in participants with bronchiectasis.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

Seven studies involving 105 participants met the inclusion criteria of this review, six of which were cross‐over in design. Six studies included adults with stable bronchiectasis; the other study examined clinically stable children with bronchiectasis. Three studies provided single treatment sessions, two lasted 15 to 21 days and two were longer‐term studies. Interventions varied; some control groups received a sham intervention and others were inactive. The methodological quality of these studies was variable, with most studies failing to use concealed allocation for group assignment and with absence of blinding of participants and personnel for outcome measure assessment. Heterogeneity between studies precluded inclusion of these data in the meta‐analysis; the review is therefore narrative.

One study including 20 adults that compared an airway oscillatory device versus no treatment found no significant difference in the number of exacerbations at 12 weeks (low‐quality evidence). Data were not available for assessment of the impact of ACTs on time to exacerbation, duration or incidence of hospitalisation or total number of hospitalised days. The same study reported clinically significant improvements in HRQoL on both disease‐specific and cough‐related measures. The median difference in the change in total St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score over three months in this study was 7.5 units (P value = 0.005 (Wilcoxon)). Treatment consisting of high‐frequency chest wall oscillation (HFCWO) or a mix of ACTs prescribed for 15 days significantly improved HRQoL when compared with no treatment (low‐quality evidence). Two studies reported mean increases in sputum expectoration with airway oscillatory devices in the short term of 8.4 mL (95% confidence interval (CI) 3.4 to 13.4 mL) and in the long term of 3 mL (P value = 0.02). HFCWO improved forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) by 156 mL and forced vital capacity (FVC) by 229.1 mL when applied for 15 days, but other types of ACTs showed no effect on dynamic lung volumes. Two studies reported a reduction in pulmonary hyperinflation among adults with non‐positive expiratory pressure (PEP) ACTs (difference in functional residual capacity (FRC) of 19%, P value < 0.05; difference in total lung capacity (TLC) of 703 mL, P value = 0.02) and with airway oscillatory devices (difference in FRC of 30%, P value < 0.05) compared with no ACTs. Low‐quality evidence suggests that ACTs (HFCWO, airway oscillatory devices or a mix of ACTs) reduce symptoms of breathlessness and cough and improve ease of sputum expectoration compared with no treatment (P value < 0.05). ACTs had no effect on gas exchange, and no studies reported effects of antibiotic usage. Among studies exploring airway oscillating devices, investigators reported no adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

ACTs appear to be safe for individuals (adults and children) with stable bronchiectasis and may account for improvements in sputum expectoration, selected measures of lung function, symptoms and HRQoL. The role of these techniques in acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis is unknown. In view of the chronic nature of bronchiectasis, additional data are needed to establish the short‐term and long‐term clinical value of ACTs for patient‐important outcomes and for long‐term clinical parameters that impact disease progression in individuals with stable bronchiectasis, allowing further guidance on prescription of specific ACTs for people with bronchiectasis.

Plain language summary

Airway clearance techniques in bronchiectasis

Bottom line: We reviewed the evidence to determine whether airway clearance techniques (ACTs) are helpful for people with bronchiectasis. The sparse data that we found suggest that their effect on the number of exacerbations (flare‐ups) is unknown. Airway clearance techniques seem to be safe, and two small studies indicate that they may improve quality of life. Airway clearance techniques also led to clearance of more mucus from the lungs and some improvement in defined measures of lung function, but no change in oxygenation. A reduction in symptoms of breathlessness, cough and mucus was found in one study. Other outcomes of interest were hospitalisation and prescription of antibiotics, but these were not yet reported. Overall, the impact of ACTs on individuals experiencing chest infection is unknown. On the basis of this information, current guidelines for treating bronchiectasis recommend routine assessment for ACTs and prescription as required.

What evidence did we find and how good was it? Seven studies included 105 people with bronchiectasis. Only two of these studies lasted for six months; the others were completed over a shorter time frame or involved a single treatment session. From these, it is difficult to know whether any improvement would be maintained over a longer term. The methods used to conduct these trials were not well reported; therefore, we believe that overall the evidence was of low quality. Three studies were funded by research institutions or governmental organisations; the other four studies did not report any funding.

What is bronchiectasis? Bronchiectasis is a lung condition in which the airways become abnormally widened, leading to a build‐up of excess mucus. People with bronchiectasis frequently report symptoms of cough, excessive mucus production and breathlessness and are at risk of chest infection.

What are airway clearance techniques? Physiotherapy treatment in the form of ACTs is often prescribed to help people clear mucus from their lungs.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Airway clearance techniques for individuals with stable bronchiectasis.

| ACTs for individuals with stable bronchiectasis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: individuals with stable bronchiectasis

Settings: hospital (outpatient department)

Intervention: airway clearance techniques (ACTs) Control: no intervention, sham intervention (placebo) or coughing alone | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Airway clearance techniques (ACTs) | |||||

| Number of exacerbations of bronchiectasis Frequency of acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis Follow‐up: mean 3 months | 35 per 100a | 25 per 100 (8 to 79)a | RR 0.71 (0.23 to 2.25) | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,c | Duration of each intervention was 3 months of PEP‐based ACT |

| Hospitalisations | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | Not reported |

| Health‐related quality of life (disease‐specific) Scale from 0 to 100; lower score indicates better HRQoL. SGRQ total score consists of weighted scores from 3 domains Follow‐up: mean 3 months | Median health‐related quality of life (disease‐specific) in control groups was ‐0.7 pointsa | Median health‐related quality of life (disease‐specific) in intervention groups was 7.5 lowera | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,d | Lower score post intervention was favourable, indicating improvement in HRQoL | |

|

Health‐related quality of life (cough‐specific)

Leicester Cough Questionnaire Scale from 0 to 133; higher score indicates better HRQoL. Contains 19 questions from 3 domains on a Likert scale Follow‐up: mean 3 months |

Median HRQoL (cough‐specific) in control groups was 0.0 pointsa | Median HRQoL (cough‐specific) in intervention groups was 1.3 highera | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,e | Higher score post intervention was favourable, indicating improvement in HRQoL cough‐related | |

|

Health‐related quality of life (health status) COPD Assessment Tool. Scale from 0 to 5; higher score indicates worse HRQoL Contains 10 questions with 5‐point Likert scale Follow‐up: mean 15 days |

Mean health status score in control group was 9.9 points | Mean health status score in intervention groups was 14.8 points lower (11.6 to 18 points lower) | MD ‐14.8 (95% CI ‐18.0 to ‐11.6) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,e |

Two interventions (high‐frequency chest wall oscillation and mixed ACTs) compared with control. Lower score post intervention was favourable, indicating improvement in health status |

|

Respiratory symptoms (symptoms) Breathlessness, Cough and Sputum Scale Scale from 0 to 12. Lower score indicates fewer symptoms Follow‐up: mean 15 days |

Mean respiratory symptom score was 3.1 points | Mean respiratory symptom score in intervention groups was 4.4 points lower (3.2 to 5.5 points lower) | MD ‐4.4 (95% CI ‐5.5 to ‐3.2) | 30 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowb,e |

Two interventions (high‐frequency chest wall oscillation and mixed ACTs) compared with control |

| Adverse events (AEs) | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | See comment | 2 studies reported no AEs related to use of PEP‐based ACTs. 2 studies reported no AEs |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACTs: airway clearance techniques; CI: confidence interval; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life; PEP: positive expiratory pressure; RR: risk ratio; SGRQ: St George's Respiratory Questionnaire. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

aStudy was a randomised cross‐over trial bAbsence of allocation concealment; participants and therapists unblinded (risk of bias ‐1) cSmall number of participants and few events evident (imprecision ‐1) dTwo studies assessed this outcome; only 1 study provided sufficient data for pooling (imprecision ‐1)

eSmall number of participants (imprecision ‐1)

Background

People with non‐cystic fibrosis (non‐CF) bronchiectasis commonly cough up mucus, have low fitness levels and are at risk of chest infection.. The optimal treatment for reducing these symptoms is unknown.

Description of the condition

Non‐CF bronchiectasis is a chronic and progressive respiratory condition characterised by irreversible and abnormal dilation of the bronchial lumen (Barker 2002; Chang 2008). Multiple causes of bronchiectasis range from immunological disorders to systemic and other respiratory conditions (McShane 2013). Although the global prevalence of this condition is not well described, it remains a major source of morbidity, with increased hospitalisation and medical therapy (AIHW 2005; King 2005; King 2006a; Weycker 2005), and the mortality rate has been reported to range from 10% to 16% over a four‐year period (Goeminne 2012; Loebinger 2009; Onen 2007). Bronchiectasis commonly develops following an infective insult to the airways, often against a background of genetic susceptibility, and may affect both children and adults. Subsequent impairment of mucociliary clearance contributes to persistent presence of micro‐organisms in the bronchial tree and subsequent colonisation (Cole 1986; Neves 2011). This leads to chronic inflammation, which further disrupts mucociliary function, resulting in tissue damage and remodelling (Gaga 1998), and a cycle of infection and inflammation that is characterised by frequent acute exacerbations (Chang 2008; King 2005). Sputum retention can result in mucous plugs, which reduce the diameter of airways and contribute to airflow obstruction (McShane 2013; van der Schans 2002). A decline in respiratory function and frequent acute exacerbations are independent predictors of poor prognosis in bronchiectasis (Loebinger 2009; Martinez‐Garcia 2007). Clinically, this underlying pathophysiology is characterised by chronic cough with purulent sputum production as well as dyspnoea and fatigue ‐ symptoms that contribute to diminished health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (King 2006b; Martinez‐Garcia 2005; Tsang 2009; Wilson 1997). This profile of sputum retention combined with airway damage lends support to the application of treatment techniques that seek to facilitate sputum removal (McShane 2013; Pasteur 2010).

Description of the intervention

Airway clearance techniques (ACTs) are non‐pharmacological interventions that facilitate removal of secretions from the lungs (McCool 2006). A myriad of ACTs are applied in clinical practice, including positioning, gravity‐assisted drainage, manual techniques, various breathing strategies, directed coughing, positive expiratory pressure (PEP) devices, airway oscillating devices and mechanical tools that are applied to the external chest wall. These ACTs may be used as isolated techniques or in combination.

How the intervention might work

The rationale by which ACTs may improve sputum clearance includes changes in lung volume, pulmonary pressure and expiratory flow; use of gravity; and the application of directly compressive or vibratory forces. These mechanisms may modify the viscoelastic properties of pulmonary secretions and may augment gas‐liquid interactions (Kim 1986; Kim 1987) and cilial beat frequency (Hansen 1994) to enhance sputum clearance. Limited evidence suggests that ACTs have a beneficial effect on sputum clearance (Bateman 1981; Sutton 1983; Sutton 1985) and sputum volume (Eaton 2007; Gallon 1991) in people with bronchiectasis. Whether the beneficial effects of ACTs extend to other outcomes, leading to fewer acute exacerbations, reduced incidence of hospitalisation and improved HRQoL in this population, remains unknown.

Why it is important to do this review

Current guidelines for non‐CF bronchiectasis advocate for prescription of ACTs, irrespective of clinical state (Chang 2015; Pasteur 2010). However, the clinical utility of ACTs in bronchiectasis is unclear (Tsang 2004). Previous research has reported conflicting results, for instance, gravity‐assisted drainage with or without breathing exercises improved transport of mucus and production of sputum in some studies (Eaton 2007; Gallon 1991; Kaminska 1988; Sutton 1983) but had no effect in others (Tsang 2003; van Henstrum 1988). The difficulty involved in determining efficacy of ACTs in bronchiectasis may be related to the heterogeneity of the disease, including variability in sputum volume, and in the extent of ventilatory defects (Tsang 2004). In addition, clinical status may be of significance, with response to treatment influenced by severity of respiratory symptoms, degree of inflammation and infection and extent of airflow obstruction. Finally, ACTs that apply PEP to the airways may have different physiological effects when compared with those that do not use positive pressure, such as augmentation of lung volumes (Garrard 1978) and prevention of early airway closure during expiration (Oberwaldner 1986).

This review has been conducted to summarise the results of literature evaluating the safety and efficacy of ACTs in people with acute and stable bronchiectasis, and to determine the effects of ACTs on rates of acute exacerbation, incidence of hospitalisation and HRQoL. This review is an update of a previous version analysing the effects of ACTs in bronchiectasis (Lee 2013), which originated from an earlier review conducted to analyse the effects of ACTs in both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis (Jones 1998).

Objectives

Primary

To determine effects of ACTs on rates of acute exacerbation, incidence of hospitalisation and HRQoL in individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis.

Secondary

To determine whether:

ACTs are safe for individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis; and

ACTs have beneficial effects on physiology and symptoms among individuals with acute and stable bronchiectasis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomised controlled trials in which a prescribed ACT regimen was compared with no intervention, sham intervention or coughing alone in individuals with acute or stable bronchiectasis. Both parallel‐group and cross‐over designs were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Adults and children with bronchiectasis of any origin, diagnosed according to the investigator's definition based on plain‐film chest radiography, bronchography, high‐resolution computed tomography (HRCT) or physician diagnosis of bronchiectasis, were included. No exclusions were based on age, gender or physiological status. Participants were considered to have an exacerbation of bronchiectasis if they had an exacerbation of symptoms (dyspnoea, increased cough or sputum production) requiring medical treatment, including hospitalisation. Participants were considered to have stable bronchiectasis if they were free from an exacerbation requiring medical treatment for a period of four weeks (O'Donnell 1998), or as defined by investigators. We planned to analyse studies involving participants with acute bronchiectasis separately from studies involving participants with stable bronchiectasis; however, we identified no eligible studies of participants with acute bronchiectasis. We excluded studies of participants with bronchiectasis who also had documented evidence of COPD, chronic bronchitis, cystic fibrosis (CF) or asthma (baseline forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) > 15% reversibility in more than 50% of participants), or who were breathing via an artificial airway.

Types of interventions

Intervention: We considered any technique used with the primary intent of clearing sputum from the airways, including, but not restricted to, 'conventional techniques', breathing exercises, PEP or airway oscillating devices and mechanical devices, but excluding suctioning. We did not include inhalation therapy, as its mechanism of action for clearing mucus differs from that of ACTs. We included interventions consisting of a single short‐term (less than seven days) or long‐term (longer than seven days) treatment.

Control: This comprised no intervention, sham intervention (placebo) or coughing alone.

To be eligible for inclusion, a study had to compare an ACT versus a control condition. When multiple ACTs were investigated in a single study, data had to reflect independent comparisons of each ACT versus the control condition. We did not include studies comparing only one ACT versus another.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Rate of, duration of or time to acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis, as defined by investigators. The minimal time over which data related to rates of acute exacerbation were obtained was one month, during which ACTs may have continued.

-

Incidence of hospitalisation for bronchiectasis:

for stable bronchiectasis ‐ time to hospitalisation, number of hospital admissions or hospital days; or

for exacerbation of acute bronchiectasis ‐ length of hospital stay, time to re‐admission, number of hospital admissions or hospital days.

Quality of life, as measured by a generic or disease‐specific HRQoL instrument.

Secondary outcomes

Pulmonary function (e.g. FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory flow between 25% and 75% of vital capacity (FEF25‐75%), peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), total lung capacity (TLC), residual capacity (RC), functional residual capacity (FRC)).

Gas exchange (e.g. blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2), partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood (PaCO2)).

Symptoms (e.g. dyspnoea, cough), with all measures of symptoms eligible for inclusion.

Clearance and expectoration of mucus (e.g. mucociliary transport, sputum weight (dry and wet), sputum volume).

Days of antibiotic usage.

Adverse events (decline in lung function, desaturation, haemoptysis, arrhythmia, tachypnoea).

Mortality (all‐cause).

Participant withdrawal.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The previously published version pf this review included searches up to October 2012. The search period for this update is October 2012 through November 2015.

We identified studies using the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of Trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) and PsycINFO, and from handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (see Appendix 1 for details of sources and search methods). We searched all records in the CAGR using the search strategy in Appendix 2, and the PEDro database using the terms provided in Appendix 3.

Both databases were searched from the period of their inception to November 2015 (CAGR) and again in March 2015 (PEDro), with no language or publication restriction.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references and reviewed all relevant conference abstracts to identify additional articles. We contacted the authors of identified trials and experts in the field to identify other published and unpublished studies when possible. We checked clinical trials registries for current studies and those that might have been recently completed.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently coded studies identified in the literature searches for relevance by examining titles, abstracts and keyword fields as follows.

INCLUDE: Study met all review criteria.

UNCLEAR: Study appeared to meet some review criteria, but available information was insufficient for categorical determination of relevance; or

EXCLUDE: Study did not categorically meet all review criteria.

Two review authors (AL, AB) used a full‐text copy of studies in categories INCLUDE and UNCLEAR to decide on study inclusion. We resolved disagreements by consensus and kept a full record of decisions for calculation of simple agreement and a kappa statistic.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AL, AB) independently extracted data using a prepared checklist. We compared the generated data and resolved discrepancies by consensus. One review author (AL) entered data into RevMan 5.1 (RevMan 2015) and performed random checks on accuracy. We contacted the authors of included studies to verify data extracted from their study when possible and to request details of missing data when applicable.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AL, AB) conducted a 'Risk of bias' assessment in accordance with recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed risk of bias according to six domains of potential sources of bias (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, loss to follow‐up, selective outcome reporting and other possible bias). We graded bias as low, high or unclear, and resolved discrepancies by consensus. We summarised results in a 'Risk of bias' table.

Measures of treatment effect

We summarised the findings of all included studies. For continuous variables, we recorded median or mean differences from baseline and post‐intervention values with interquartile ranges (IQRs) or standard deviations. When possible, for pooled analyses, we used RevMan 5.3 to calculate mean differences (MDs) for outcomes measured with the same metrics, or standardised mean differences (SMDs) for outcomes measured with different metrics, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

We had intended to analyse exacerbations and hospitalisations as dichotomous (yes/no) or ratio (rate, frequency) data by analysing scores from instruments measuring quality of life and symptoms as continuous or ordinal data. As quantitative data were analysed using non‐parametric tests from cross‐over trials (Guimaraes 2012; Kurz 1997; Murray 2009; Sutton 1988), with results available in median (IQR), we could not undertake analysis using RevMan 2015. Therefore, we reported these results in a narrative format. For quantitative data from cross‐over trials that had been analysed by trial authors using parametric tests (Figueiredo 2010; Svenningsen 2013), we performed analysis using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan 2015 when data were available in an appropriate form, with the first arm used for analysis. For cross‐over trials, we calculated paired MDs between interventions and their standard errors (SEs) by using MDs between interventions and their SDs, or by using P values reported in the manuscript.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of studies with missing data and asked them to provide data if possible.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If we are able to include sufficient data, we will assess heterogeneity within each outcome between comparisons by calculating I2 statistics.

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to use visual inspection of funnel plots to assess publication bias; however, the number of included trials was too small (10 or more studies are needed).

Data synthesis

We intended to analyse data from studies on exacerbations of acute bronchiectasis separately from data derived from studies of stable bronchiectasis; however, we identified no studies pertaining to people with an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis. We reported studies according to the duration of post‐intervention follow‐up, as follows: 'immediate' (within 24 hours) and 'long‐term' (greater than 24 hours). Within each participant group, we pooled data that were both clinically and statistically homogeneous by using a fixed‐effect model. We pooled data that were clinically homogeneous but statistically heterogeneous by using a random‐effects model. We did not pool data that were clinically heterogeneous. We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to interpret findings (Langendam 2013; Schunemann 2008), and we used the GRADE profiler (GRADEPRO) to import data from Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2015) to create 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables provide outcome‐specific information related to the overall quality of evidence generated by studies included in the comparison and the sum of available data on the outcomes considered. We included the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables: numbers of exacerbations, hospitalisations, HRQoL (disease‐specific, generic and cough‐related), symptoms and adverse events. We calculated risk ratios by using GRADEPRO. For assessments of the quality of evidence for each outcome, we downgraded evidence from 'high quality' by one level for serious study limitations (risk of bias), indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to conduct one subgroup analysis, specified a priori, to identify potential influences on pooled results.

PEP devices: ACTs using PEP may have differing physiological effects and outcomes compared with ACTs not using PEP.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to analyse the effects of allocation concealment, assessor blinding and intention‐to‐treat analysis on results. However, insufficient numbers of included studies precluded this analysis. We will perform sensitivity analyses in future updates if additional trials become available.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification for complete details.

Results of the search

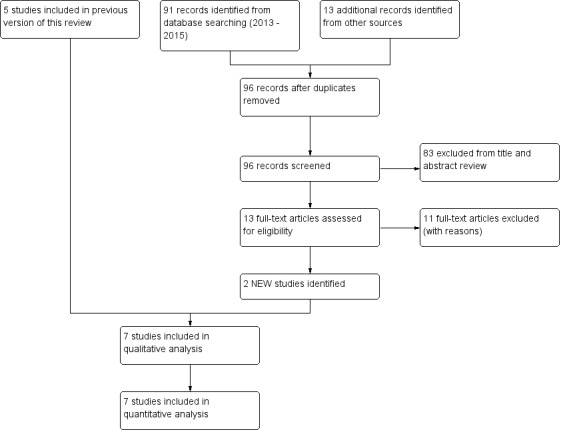

In the original version of this review, review authors identified 63 records through the initial database search, and an additional three records through review of reference lists and clinical trial registries. From these studies, they retrieved nine full‐text papers for further review. Agreement on these full‐text papers between review authors had a kappa = 0.97, indicating excellent agreement. The original review included five studies. The 2015 updated search of databases yielded 91 references (CAGR and PEDro databases) and an additional 13 studies obtained from clinical trial registries of potential studies, yielding 104 studies. After discarding duplicates, we included a total of 96 studies. We made attempts to contact the authors of two studies rated 'unclear' to determine their suitability for inclusion in the review, and obtained two responses. We excluded 83 studies on the basis of title and abstract, including three studies awaiting classification and nine that were ongoing; we could not included these in the analysis. We assessed 13 studies for eligibility via full‐text review. We excluded 11 studies, as they did not meet the review criteria. Two studies from the updated search met the inclusion criteria. Review authors agreed on 12 out of 13 articles following full‐text review (92%), with kappa = 0.82, indicating substantial agreement. We included in this review a total of seven studies from the original and updated searches (Figure 1). Common reasons for exclusion were that studies did not include a control group (n = 29), did not undertake ACTs (n = 28) or included a mixed disease group (n = 9). We outlined full details of excluded studies and those awaiting classification in the Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification tables.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Refer to Characteristics of included studies.

Design

This review comprises six randomised cross‐over trials and one randomised controlled trial.

Participants

The seven included studies involved 102 participants and sample sizes ranging from eight to 37 participants. Six studies examined clinically stable adult participants (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013), and one study focused on clinically stable children (Kurz 1997). Six studies diagnosed bronchiectasis on the basis of HRCT (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013), and one study did not specify the diagnostic criteria used (Kurz 1997). Among adults, the age of participants ranged from 36 to 75 years in four studies (Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013), and between 47 and 56 years in two studies (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012), and the age range of children with bronchiectasis was six to 16 years (Kurz 1997). Of the six studies that documented disease severity, lung function ranged from FEV1 of 1.2 L to 1.7 L (Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988), 53% to 65% predicted (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012) and 69% to 76% predicted (Murray 2009; Svenningsen 2013). Two studies commented that participants were naïve to the forms of airway clearance therapy included in the trial (Figueiredo 2010; Murray 2009).

Intervention

The duration of each intervention ranged from a single treatment in three studies (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Sutton 1988) to longer‐term treatment over 15 to 21 days in two studies (Nicolini 2013; Svenningsen 2013) to a six‐month treatment duration, with 90 days (12 weeks) for each arm, in two other studies (Kurz 1997; Murray 2009). Three studies detailed the duration of the washout period between interventions, which ranged from one week in two short‐term studies (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012) to one month in the longer‐term study (Murray 2009), with outcome measures collected only during the study, and no long‐term follow‐up beyond the intervention.

Two studies compared three techniques: Guimaraes 2012 compared airway oscillating devices versus slow expirations with the glottis open from the FRC to the residual volume (RV), performed in the lateral decubitus position, with the affected lung in the dependent position ('L'expiration Lente Totale Glotte Ouverte en Decubitus Lateral' (ELTGOL)) versus resting, and Nicolini 2013 examined high‐frequency chest wall oscillation (HFCWO) versus chest physiotherapy (gravity‐assisted drainage with slow expiration in the lateral decubitus position or PEP therapy or oscillating PEP therapy) versus usual medical care. One study compared gravity‐assisted drainage and forced expiratory technique (FET) versus resting (Sutton 1988). Two studies compared airway oscillating devices versus sham PEP, with sham therapy consisting of a flutter with the steel ball removed (Figueiredo 2010; Kurz 1997), with no modification made to the size of the orifice to minimise the opportunity of achieving therapeutic PEP (Tambascio 2011), and two studies examined the effects of airway oscillating devices versus a suitable control of standard care (Murray 2009; Svenningsen 2013).

It was not possible to pool data for meta‐analyses from studies because of the heterogeneity of study designs (differing types of interventions) and differing time frames and outcomes.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 75 studies. Most excluded studies compared different ACTs versus each other without including a suitable control, or used interventions that were not ACTs. Other reasons for exclusion were lack of randomisation, inclusion of mixed disease groups, for which data exclusively for participants with bronchiectasis were not available, and use of outcome measures that were not of interest for this review. Full details of reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Nine studies are ongoing (Characteristics of ongoing studies), and three are awaiting classification and will be assessed for eligibility in future updates of this review.

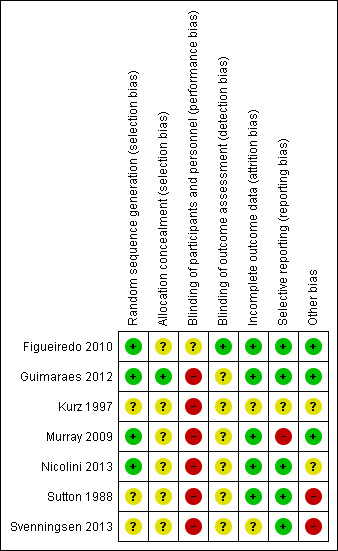

Risk of bias in included studies

We noted some variation in risk of bias across included studies. Some judgements were limited by inadequate reporting, which made determining the true quality of the study design difficult. Refer to the Characteristics of included studies table for full details of risk of bias across all studies, and to Figure 2 for a summary of our judgements on potential risks of bias across studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Four studies reported sufficient detail to confirm low risk of bias for randomisation sequence (Figueiredo 2010; Kurz 1997; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013), and three studies were unclear (Guimaraes 2012; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013). Only one study provided evidence of allocation concealment (Guimaraes 2012).

Blinding

All seven included studies were rated as having high risk of bias due to inadequate blinding of participants. Two studies attempted to blind participants to knowledge of the intervention by using a sham ACT (Figueiredo 2010; Kurz 1997); however, this did not eliminate the possibility that specific outcomes would not be affected. One study was rated as having low risk of detection bias; although blinding of all assessors could not be guaranteed, the objective outcomes are not likely to be influenced by knowledge of the intervention (Figueiredo 2010). The remaining six studies did not report sufficient detail to reveal the level of risk of detection bias (Guimaraes 2012; Kurz 1997; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

We rated six included studies as having low risk of bias due to complete outcome data (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013). One study did not report the number of dropouts; in this case, the risk of bias was unclear (Kurz 1997).

Selective reporting

Two studies were registered on a clinical trial registry (Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013). Five studies rated well and were assigned low risk of bias (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013), with documented findings for all pre‐specified outcomes. One study was rated as having high risk of bias because not all outcome measures were reported (Murray 2009), and one had unclear risk (Kurz 1997).

Other potential sources of bias

Six cross‐over trials used appropriate statistical analyses. One study did not include a washout period between oscillating PEP and no treatment (Svenningsen 2013). Three studies employed adequate washout periods (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009); however, two studies did not specify the length of the washout period (Kurz 1997; Sutton 1988).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We were able to include data from seven studies including 105 participants in a quantitative and narrative synthesis, six of which were conducted in adult participants with stable bronchiectasis (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013) and one in children (Kurz 1997).

Primary outcome: exacerbations and hospitalisations

One study evaluated the long‐term impact of an airway oscillatory device on the frequency of exacerbations in 20 adults (Murray 2009) and found no significant differences between groups at 12 weeks (five exacerbations with ACT vs seven exacerbations without ACT; P value = 0.48). No available data showed the impact of the airway oscillating device on time to exacerbation, duration of or incidence of hospitalisation or total number of hospitalised days.

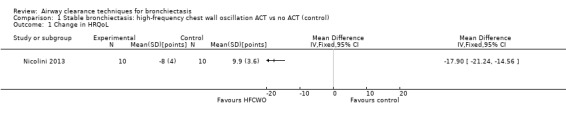

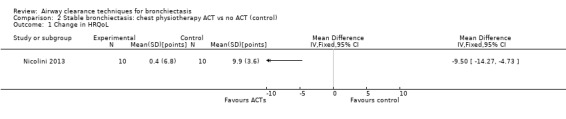

Primary outcome: quality of life

Three studies explored the effects of airway clearance techniques on HRQoL (Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Svenningsen 2013). One study (Murray 2009) of 20 participants investigated the effect of an airway oscillatory device on HRQoL, providing long‐term data that show significantly lower (better) cough‐related quality of life according to Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) total scores following 12 weeks of twice‐daily ACTs compared with control (median difference of 1.3; P value = 0.002). This improvement is equivalent to the minimal important difference for the LCQ total score (Raj 2009). Significant improvement in the physical (P value = 0.002), psychological (P value < 0.0001) and social (P value = 0.02) impact of coughing was also reported. This airway oscillatory device also showed significant improvement in median values in disease‐specific HRQoL according to St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total scores (intervention median ‐7.8 (IQR ‐14.5 to ‐0.99); control ‐0.7 (IQR ‐2.3 to 0.05); median difference 8.5 units in favour of improvement; P value = 0.005 (Wilcoxon)). This exceeds the minimal important difference for the SGRQ (Jones 2005). In contrast, using an airway oscillation device for 15 days did not improve disease‐specific HRQOL when the same outcome measure was used (P value > 0.05) (Svenningsen 2013). HFCWO improved HRQoL better than control (MD ‐18, 95% CI ‐21 to ‐15) (Analysis 1.1), according to CAT (the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease assessment tool) (Nicolini 2013). A mix of ACTs in the same study also improved HRQoL better than control (MD ‐10, 95% CI ‐14 to ‐5) (Analysis 2.1). However, our confidence in these patient‐reported outcomes is reduced by lack of blinding in the included trials.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 1 Change in HRQoL.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 1 Change in HRQoL.

Secondary outcome: pulmonary function

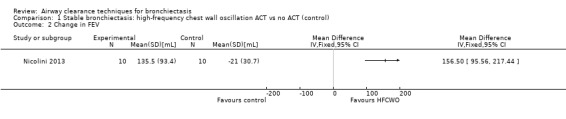

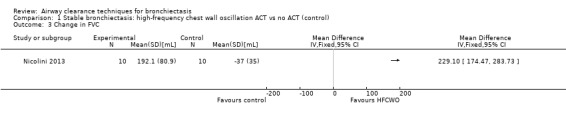

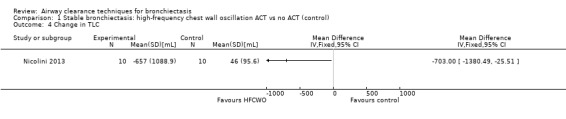

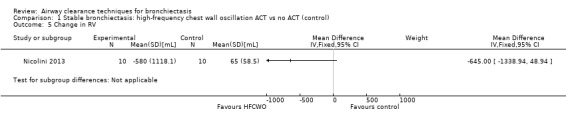

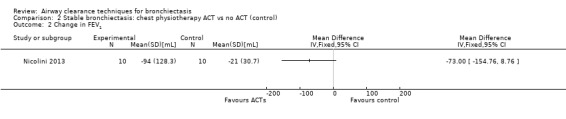

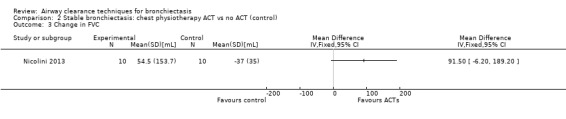

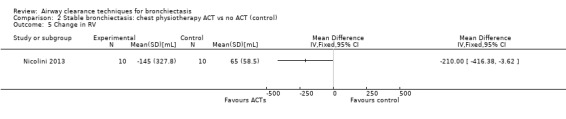

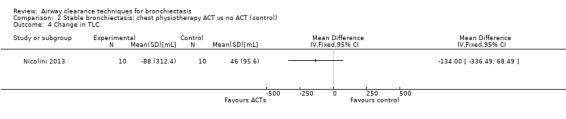

Six studies evaluated pulmonary function (Guimaraes 2012; Kurz 1997; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988; Svenningsen 2013). Quantitative analysis of data from one study showed no significant differences between ACTs (gravity‐assisted drainage and breathing technique) and control in FEV1 or FVC immediately following treatment (Sutton 1988). Similarly, Guimaraes 2012 found no significant differences between an ACT (expiration with the glottis open in the lateral posture (ELTGOL)) and control in FEV1, FEV1/FVC, FEF25‐75%, FVC, inspiratory capacity (IC) and RV/total lung capacity (TLC) immediately following a single session. However, a significant reduction in FRC and TLC was demonstrated immediately following ELTGOL versus control (median difference in FRC of 18.7%; P value < 0.05; median difference in TLC of 14.29%; P value < 0.05). In the same study, an airway oscillating device significantly reduced FRC (median difference of 30.07%; P value < 0.05), TLC (median difference of 22.9%; P value < 0.05), IC/TLC ratio (median difference of 16.07%; P value < 0.05) and RV (median difference of 26.7%; P value < 0.05) versus control. However, no significant difference in FEV1, FEV1/FVC, FVC, FEF25‐75%, IC or RV/TLC ratio was demonstrated between an airway oscillating device and control (Guimaraes 2012). Following 15 days of treatment, HFCWO was associated with significant improvement in FEV1 (MD 156.1 mL, 95% CI 95.6 to 217.4 mL) (Analysis 1.2) and FVC (MD 229.1 mL, 95% CI 174.5 to 283.7 mL) (Analysis 1.3) compared with control (Nicolini 2013). A significant reduction in TLC (MD ‐703 mL, 95% CI ‐1380.5 to ‐25.5 mL) (Analysis 1.4) with HFCWO compared with control was evident, although no difference in RV was observed (MD ‐645 mL, 95% CI ‐1338.9 mL to 48.9 mL) (Analysis 1.5). In the same study, ACTs (gravity‐assisted drainage with expiratory technique or PEP therapy or airway oscillation device) were not associated with a significant difference compared with control in FEV1 (MD ‐73 mL, 95% CI ‐154.8 to 8.76 mL) (Analysis 2.2) nor in FVC (MD 91.5 mL, 95% CI ‐6.2 to 189.2 mL) (Analysis 2.3) (Nicolini 2013). ACTs did reduce RV compared with control (MD ‐21 mL, 95% CI ‐416.4 to ‐3.62 mL) (Analysis 2.5) but had no effect on TLC (MD ‐134 mL, 95% CI ‐336.5 to 68.5 mL) (Analysis 2.4) (Nicolini 2013).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 2 Change in FEV.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 3 Change in FVC.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 4 Change in TLC.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 5 Change in RV.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 2 Change in FEV1.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 3 Change in FVC.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 5 Change in RV.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 4 Change in TLC.

Following a long‐term study in adults, Murray 2009 reported no significant differences in FEV1 (median difference 0.00 L; P value = 0.7), FVC (median difference 0.07 L; P value = 0.9) or FEF25‐75% (median difference 0.06 L; P value = 0.6) between 12 weeks of an airway oscillating device and no ACT. When applied for 15 days, an airway oscillation device was not associated with a significant change in FEV1, FVC or TLC (all P values > 0.05) compared with no treatment (Svenningsen 2013).

In children, Kurz 1997 reported differences in FEV1 of 8.86%, in PEF of 6% and in FVC of 4%, and a reduction in FRC of 6%, in favour of the longer‐term airway oscillating device over sham therapy (no P values provided).

Secondary outcome: gas exchange

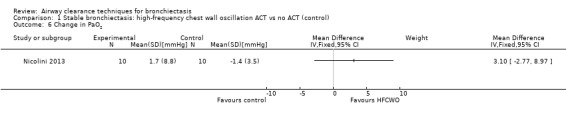

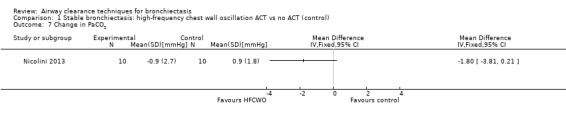

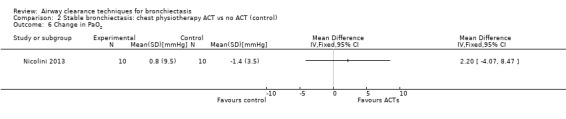

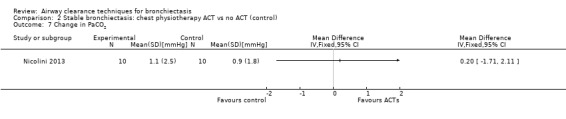

One study reported effects of ACTs on measures of gas exchange (Nicolini 2013). HFCWO had no effect on PaO2 (MD 3.1 mmHg, 95% CI ‐2.8 to 8.9 mmHg) (Analysis 1.6) nor on PaCO2 (MD ‐1.8 mmHg, 95% CI 3.8 to 0.21 mmHg) (Analysis 1.7) compared with control. In the same study, ACTs had no effect on PaO2 (MD 2.2 mmHg, 95% CI ‐4.1 to 8.5 mmHg) (Analysis 2.6) nor on PaCO2 (MD 0.2 mmHg, 95% CI ‐1.7 to 2.1 mmHg) (Analysis 2.7) compared with control.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 6 Change in PaO2.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 7 Change in PaCO2.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 6 Change in PaO2.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 7 Change in PaCO2.

Secondary outcome: symptoms

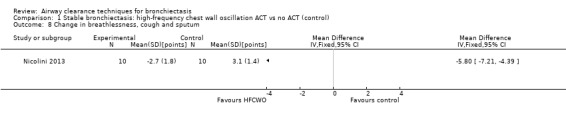

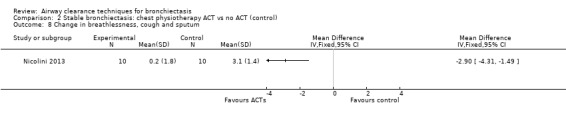

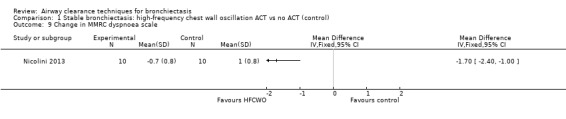

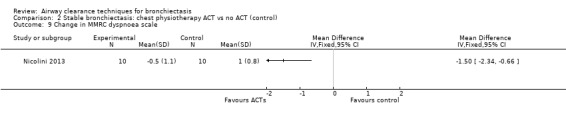

Two studies reported on symptoms (Nicolini 2013; Svenningsen 2013). Based on a combined measure of the Breathlessness, Cough and Sputum scale (BCSS), both HFCWO (MD 5.8, 95% CI ‐7.2 to ‐4.4) (Analysis 1.8) and ACTs (MD ‐2.9, 95% CI ‐4.3 to ‐1.5) (Analysis 2.8) significantly reduced symptoms of dyspnoea, cough and sputum compared with control (Nicolini 2013). A similar effect was demonstrated in the same study for functional dyspnoea for HFCWO (MD ‐1.7, 95% CI ‐2.4 to ‐1.0) (Analysis 1.9) and for ACTs (MD ‐1.5, 95% CI ‐2.3 to ‐0.7) (Analysis 2.9) compared with no treatment. According to the patient evaluation questionnaire, 15 days with the airway oscillation device significantly improved the ease of expectorating secretions (P value < 0.001) and reduced cough frequency (P value = 0.003) compared with no treatment, but had no effect on cough severity, chest discomfort or dyspnoea (P value > 0.05) (Svenningsen 2013).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 8 Change in breathlessness, cough and sputum.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 8 Change in breathlessness, cough and sputum.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 9 Change in MMRC dyspnoea scale.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control), Outcome 9 Change in MMRC dyspnoea scale.

Secondary outcome: sputum clearance

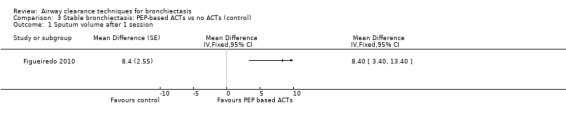

Five studies measured the effect of treatment on sputum yield (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988). A significant increase in the volume of sputum produced was noted with an airway oscillating device compared with sham therapy in Figueiredo 2010 (MD 8.40 mL, 95% CI 3.40 to 13.40 mL) (Analysis 3.1). A significant increase in 24‐hour sputum volume was reported in a long‐term study of an airway oscillating device compared with control (Murray 2009) (MD 3 mL; P value = 0.02). The third study reported a greater sputum yield with ACT (gravity‐assisted drainage and breathing technique) compared with control (22 g on ACT vs 5 g on control; P value < 0.01) (Sutton 1988). After 15 days of treatment with HFCWO, significant improvement in sputum volume was evident compared with no treatment (12.5 mL vs 3 mL; P value = 0.001), and a mix of ACTs over the same duration yielded greater sputum expectoration compared with control (7.5 mL vs 3 mL; P value = 0.04) (Nicolini 2013). In one study in which investigators measured dry sputum weight, a single session of ACT (ELTGOL) was associated with greater sputum production compared with control (0.38 g on ACT vs 0.14 g on control; P value < 0.05) (Guimaraes 2012). In the same study, no significant difference in sputum yield was reported with an airway oscillating device compared with control (0.15 g on ACT vs 0.14 g on control; P value > 0.05). According to other measures of sputum clearance, no significant improvement in mucociliary clearance was found upon radioaerosol imaging with ACTs compared with control (gravity‐assisted drainage and breathing technique) in terms of whole lung radioaerosol clearance (20% on ACT vs 17% on control; P value = not significant) nor in terms of regional (inner and outer) clearance (12% vs 11% inner region and 3% vs 2% outer region; P value > 0.05) (Sutton 1988).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Stable bronchiectasis: PEP‐based ACTs vs no ACTs (control), Outcome 1 Sputum volume after 1 session.

Secondary outcome: days of antibiotic usage

No data were available for analysis.

Secondary outcome: adverse events

Three studies reported absence of adverse events during short‐term (Figueiredo 2010) and longer‐term (Murray 2009; Svenningsen 2013) use of airway oscillating devices compared with control, which reflects the safety of these types of techniques. Four studies did not report on the occurrence of adverse events (Guimaraes 2012; Kurz 1997; Nicolini 2013; Sutton 1988).

Secondary outcome: mortality

No data were available for analysis.

Secondary outcome: participant withdrawal

Three studies reported that all participants completed the study, and no withdrawals were related to use of ACTs (Figueiredo 2010; Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009). One study reported that three children with bronchiectasis refused to use the sham therapy, but it is unclear whether this refusal occurred during the trial (withdrawal) or after the trial (refusal after participation) (Kurz 1997).

Discussion

This review aimed to determine the effects of airway clearance techniques (ACTs) compared with no treatment in individuals with bronchiectasis. Results from seven studies of 105 participants were mixed. Medium‐ or longer‐term use of specific ACTs or a combination of techniques may have clinically important effects on HRQoL in adults with stable bronchiectasis. A summary of data can be found in Table 1. Selected ACTs may increase the volume of sputum expectorated. However, their effects on lung function are variable. The impact on dynamic lung function may be specific to the types of ACTs applied and the duration of treatment. Selected non‐PEP therapy and airway oscillatory devices may reduce the degree of pulmonary hyperinflation. Reduction in specific respiratory symptoms was apparent with some types of ACTs. It is difficult to determine the clinical impact and value of ACTs across the disease spectrum of this condition because of the absence of studies in participants with an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis, the small numbers of participants overall and the limited number of ACTs tested. Pooling of data for meta‐analysis was limited by heterogeneity between studies, including differing types of ACTs applied, variation in treatment session duration and differing methods of outcome measurement applied. This prevented analysis of publication bias through funnel plots.

Symptoms of cough, sputum production and dyspnoea are typical of bronchiectasis, and HRQoL is closely linked to these symptoms (Martinez‐Garcia 2005). The positive effects of high‐frequency chest wall oscillation (HFCWO) and of a mix of ACTs on sputum production and dyspnoea as well as HRQoL (Nicolini 2013) and improved disease‐specific and cough‐related HRQoL with twice‐daily treatment with an airway oscillatory device for three months are important clinical outcomes and may influence patient compliance with treatment (Prasad 2007). These beneficial effects were apparent only after a treatment duration of 15 days or longer, suggesting that the influence of specific ACTs on HRQoL and on symptoms may be determined by treatment duration. Although only two studies included symptoms as an outcome, the positive effects of HFCWO and of a mix of PEP and non‐PEP therapy or airway oscillatory devices lend support to the physiological rationale for these techniques. However, with two studies using a cross‐over design (Murray 2009; Svenningsen 2013), absence of a placebo group suggests that these results should be viewed with caution. Lack of information regarding inclusion of a blinded assessor for this outcome in these studies potentially introduces a degree of bias in the results. Although no effect on exacerbation rate was noted in this longer‐term study (Murray 2009), absence of a follow‐up period after completion of treatment during which exacerbations may be collated limits the ability of investigators to accurately interpret the impact of airway oscillatory devices on exacerbation rates. In addition, the effect of this form of ACT on the incidence of hospitalisation is unknown and has not been explored. As both of these primary outcomes are of relevance to the clinical profile, disease progression and the prognosis of this condition (Loebinger 2009), this important area requires further examination.

Although acute improvement in lung function following ACTs is likely to reflect secretion displacement within the airways (from the periphery to the proximal airways), change in lung function over time in individuals with bronchiectasis (King 2005; Martinez‐Garcia 2007) is influenced by the frequency and severity of acute exacerbations (Elborne 2007). The short‐term impact of ACTs on lung function has remained variable. It appears that HFCWO did have a positive influence on dynamic lung function; however, this did not translate into an advantage in terms of gas exchange. Improved forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) in cystic fibrosis (CF) with this type of ACT have been previously demonstrated and were accompanied by a reduction in functional residual capacity (FRC) (Braveman 2007; Kempainen 2010). The rationale is that when delivered with 10 to 15 Hz, this technique maximises oscillatory airflow while minimising small airway closure (Braveman 2007; Kempainen 2010). In contrast, this effect was not evident with other techniques, with no change in dynamic lung function observed with gravity‐assisted drainage and breathing techniques compared with no treatment (Murray 2009; Sutton 1988), and the effects of airway oscillatory devices were varied, with some reports of improvement with long‐term treatment (Kurz 1997) and other reports of no benefit (Guimaraes 2012; Murray 2009). Although this may suggest that the clinical value of these techniques for short‐ or long‐term management is unclear, findings are predominantly consistent with previous reports demonstrating that measures of airflow obstruction did not reflect changes in sputum transport and are considered an insensitive reflection of the effectiveness of ACTs (Cochrane 1977). Any changes in lung function do not appear to be reflected by gas exchange measures, despite the rationale that HFCWO improves alveolar ventilation homogenisation (Braveman 2007; Isabey 1984). In contrast, a mix of techniques appear to have a positive impact on pulmonary hyperinflation (Guimaraes 2012; Kurz 1997; Nicolini 2013), which is a feature of non‐CF bronchiectasis (Koulouris 2003; Martinez‐Garcia 2007a). It has been suggested that in people with CF, measures of static lung volume rather than dynamic lung volume may provide a clearer reflection of the impact of ACTs on sputum transport, although the precise mechanism is not clear (Regnis 1994). In addition, their effect on static lung volumes may be dependent on the type of ACT provided, with some studies demonstrating a positive effect on total lung capacity (TLC) with airway oscillatory devices (Guimaraes 2012; Nicolini 2013) that is greater than with ELTGOL (Guimaraes 2012), and others reporting benefit with a mix of ACTs (Nicolini 2013). One study showed considerable baseline variation in both static lung volume measures (residual volume (RV) and TLC) between groups undertaking HFCWO, a mix of ACTs and no treatment (Nicolini 2013). No adjustment for this variation was included within the statistical comparison between groups, and for this reason, the effects of both HFCWO and a mix of ACTs on RV and TLC compared with no treatment should be interpreted with caution, with the magnitude of the difference between groups likely to be smaller than reported. Even in consideration of this limitation, the differing degree of impact on hyperinflation suggests that the mechanism behind this effect may vary between techniques and may be influenced by the baseline static lung volume of participants. The positive pressure generated during expiration is designed to provide a splinting effect on the airways, to prevent dynamic airway collapse and to enhance expiratory flow (Flude 2012). In contrast, ELTGOL (Guimaraes 2012) may target the specific lung volumes associated with pulmonary hyperinflation.

Several studies found a significant increase in a key clinical outcome of sputum expectoration immediately following treatment up to one hour post treatment or over 24 hours with airway oscillatory devices compared with no intervention (Figueiredo 2010; Murray 2009; Nicolini 2013) or with ELTGOL ACTs (Guimaraes 2012; Sutton 1988). One potential confounding factor is the difference between studies in the methods of measurement of sputum volume used, with three studies using wet volume (Figueiredo 2010; Murray 2009; Sutton 1988) and one study using dry weight (Guimaraes 2012). The quantification of wet volume may be influenced by a person's reticence to expectorate, saliva contamination or swallowing of secretions (Arens 1994; Williams 1994), which may lead to incorrect estimation of the outcome. In contrast, contamination with saliva may be corrected in part by drying sputum and measuring dry weight (van der Schans 2002), which may lend greater support to selected ACTs that applied this method of evaluation. Even with the approach of using dry weight of sputum, the sputum density of individual people may demonstrate diurnal variation (van der Schans 2002) and may be influenced by hydration levels (Boucher 2010). Despite these limitations, these studies provide preliminary support of ACTs by addressing a symptom commonly associated with bronchiectasis.

Study of the contrasting effects of airway oscillatory devices versus ELTGOL on sputum production has been limited, with only one study demonstrating an immediately greater sputum yield with ELTGOL (Guimaraes 2012). The physiological rationale for this form of ACT involves promoting two‐phase gas‐liquid interaction to facilitate mucociliary clearance; in contrast, the primary mechanism of the airway oscillatory device involves providing a splinting effect on the airways, improving collateral ventilation and altering sputum rheology (Tambascio 2011). This may account for the different clinical effect.

Each ACT applied in the included studies is comparable with those frequently prescribed in people with CF (Flume 2009; van der Schans 2000), suggesting that the rationale behind the prescription is considered to be similar between different patient populations (Bott 2009). However, compared with studies in CF, fewer types of ACTs have been compared with a control condition. Despite this fact, selected effects of these treatments are similar, and they lead to improvement in sputum production over the short term (van der Schans 2000). Direct comparison of the benefits of ACTs for bronchiectasis versus CF with other outcome measures incorporated into this review is limited because ACT is considered to be a cornerstone of management in CF, and, for this reason, long‐term trials in this patient population are lacking. Recently, clinical studies of ACTs in bronchiectasis have focused on comparing the effects of different types of techniques over the short and long term (Eaton 2007; Patterson 2004; Patterson 2005; Patterson 2007; Savci 1998; Thompson 2002; Tsang 2003), an approach that is similar in CF. However, this review did not incorporate results from these studies comparing the effects of different types of ACTs only, without a control group. The approach in the current review was to establish the value of ACTs compared with no ACTs in individuals with exacerbation of acute or stable bronchiectasis, rather than comparing the effects of specific techniques whose physiological rationale may differ. With current clinical practice guidelines and recommendations for bronchiectasis advocating for ACTs as part of management (Chang 2015; Hill 2011; King 2010; Pasteur 2010), comparison and contrast of the effects of different types of ACTs in this patient group are needed to clarify the role of routine ACT prescription in bronchiectasis. Current findings suggest benefit, but further research is needed to establish the physiological and clinical effects of different types of ACTs to inform clinical practice.

Summary of main results

In individuals with stable bronchiectasis, data from a small number of studies show that ACTs result in improvement in HRQoL, fewer respiratory symptoms, greater sputum expectoration and improvement in pulmonary hyperinflation. Preliminary work suggests lack of change in gas exchange with ACTs, but future studies are needed to confirm the magnitude of these effects and the impact on dynamic measures of lung function across a range of ACTs. No effect of ACTs on exacerbation frequency was evident. Future studies with blinded assessors are required to investigate the effects of ACTs on rates of exacerbation, incidence of hospitalisation and antibiotic usage. The impact of ACTs on individuals with an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis has not been established.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most studies have not specified the underlying cause of bronchiectasis nor the extent of bronchiectasis or functional level. Therefore, the influence of these factors on the effectiveness of specific ACTs is difficult to determine. From the two studies evaluating single treatment sessions, it is difficult to generalise findings to the overall population. We hypothesised that the effect of ACTs may differ in those experiencing an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis compared with those in a stable state. However, with all studies conducted in individuals in a stable clinical state, the effects of these techniques during an acute exacerbation remain unclear and require further study.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the seven studies included in this review is mixed, with small sample sizes and often unclear or high risk of bias, particularly with regard to blinding of assessors and inclusion of concealed allocation. Available data for quantitative analysis were limited by small effect size, and differing time frames and types of interventions limited meta‐analysis. These publications provided limited data on the primary outcomes of interest, and obtaining additional data from study authors was not consistently possible. The physical nature of these interventions limited the ability of investigators to blind participants and therapists, and only one study incorporated assessor blinding (Figueiredo 2010). All review outcomes were determined to be of low quality, primarily as the result of risk of bias and imprecise results, small participant numbers, small numbers of studies for all outcome and few events for specific outcomes.

Potential biases in the review process

A broad search incorporated handsearching of conference abstracts and trial registries, with inclusion of studies published only in abstract form. When clarification was necessary, study authors were contacted to confirm details of study design or to provide additional data. However, additional data were not consistently available. This may have affected some judgements regarding risk of bias and may have limited included data. Two review authors independently extracted data and resolved disagreements via discussion. These two review authors independently rated risk of bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is an update of a previous review, published in 2013. In the previous review, data suggested improvement with ACTs in HRQoL, sputum expectoration and pulmonary hyperinflation. This update also suggests positive benefit for respiratory symptoms of cough, sputum expectoration and dyspnoea with ACTs. With current clinical practice guidelines for bronchiectasis advocating for ACTs as part of management (Chang 2015; Hill 2011; Pasteur 2010), these are important clinical outcomes, which may account for the change in HRQoL reported in previous studies. The positive influence of a specific type of ACT on dynamic lung function suggests the need for better understanding of the physiological mechanisms behind each type of technique when applied in people with bronchiectasis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Airway clearance techniques appear to be safe for individuals (adults and children) with stable bronchiectasis and may lead to improvements in sputum expectoration, selected measures of lung function, patient symptoms and HRQoL. However, additional data are needed to establish the clinical value of ACTs over the short and the long term for participant‐important outcomes, including clinically important long‐term parameters that impact disease progression in individuals with stable bronchiectasis. The role of these techniques in people with an acute exacerbation of bronchiectasis remains unknown.

Implications for research.

The chronic nature of bronchiectasis makes clear the value of examining the longer‐term effectiveness of ACTs compared with no treatment, rather than effects within a single isolated treatment session. Additional adequately powered long‐term studies that include physiological outcomes such as measurement of small airway function, radioaerosol clearance and the lung clearance index may be more sensitive to change and may be more clinically useful (Horsley 2008). Inclusion of these measures together with clinically meaningful outcomes such as exacerbation rate and hospitalisation may clarify the rationale and mechanism of action of each technique. Clinical guidelines recommend that ACTs should be prescribed for individuals with clinical symptoms of cough, sputum production and radiological signs of mucus plugging (Chang 2015; Pasteur 2010). In view of this, future studies should include cross‐over study designs and blinded assessors to minimise potential bias in outcome measurement,. with the goal of providing further guidance on specific ACT prescription for people with bronchiectasis. In addition, lack of controlled trials for acute exacerbations of bronchiectasis is a matter of concern, as exacerbation is a key clinical characteristic of the condition (King 2005; Loebinger 2009). It may also be important to establish the comparative effects of different types of ACTs in individuals with bronchiectasis.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 November 2015 | New search has been performed | New literature search run |

| 13 July 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | 2 new studies added Elements of Background and Discussion redrafted ACTs are associated with improvements in generic HRQOL and respiratory symptoms |

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Elizabeth Stovold for assistance with developing the search strategy, and to Emma Welsh and Chris Cates for providing ongoing support throughout the review process.

Chris Cates was the Editor for this review and commented critically on the review.

The Background and Methods sections of this review are based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Airways Group.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Airways Group. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the review authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Sources and search methods for the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (CAGR)

Electronic searches: core databases

| Database | Frequency of search |

| CENTRAL (T he Cochrane Library) | Monthly |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| EMBASE (Ovid) | Weekly |

| PsycINFO (Ovid) | Monthly |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Monthly |

| AMED (EBSCO) | Monthly |

Handsearches: core respiratory conference abstracts

| Conference | Years searched |

| American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) | 2001 onwards |

| American Thoracic Society (ATS) | 2001 onwards |

| Asia Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR) | 2004 onwards |

| British Thoracic Society Winter Meeting (BTS) | 2000 onwards |

| Chest Meeting | 2003 onwards |

| European Respiratory Society (ERS) | 1992, 1994, 2000 onwards |

| International Primary Care Respiratory Group Congress (IPCRG) | 2002 onwards |

| Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) | 1999 onwards |

MEDLINE search strategy used to identify trials for the CAGR

Bronchiectasis search

1. exp Bronchiectasis/

2. bronchiect$.mp.

3. bronchoect$.mp.

4. kartagener$.mp.

5. (ciliary adj3 dyskinesia).mp.

6. (bronchial$ adj3 dilat$).mp.

7. or/1‐7

Filter to identify randomised controlled trials

1. exp "clinical trial [publication type]"/

2. (randomised or randomised).ab,ti.

3. placebo.ab,ti.

4. dt.fs.

5. randomly.ab,ti.

6. trial.ab,ti.

7. groups.ab,ti.

8. or/1‐7

9. Animals/

10. Humans/

11. 9 not (9 and 10)

12. 8 not 11

The MEDLINE strategy and randomised controlled trial filter are adapted to identify trials in other electronic databases.

Appendix 2. Search strategy to retrieve relevant trial reports from the CAGR

2015 search (via the Cochrane Register of Studies)

#1 BRONCH:MISC1

#2 MeSH DESCRIPTOR Bronchiectasis Explode All

#3 bronchiect*

#4 #1 or #2 or #3

#5 physiotherap*

#6 physical* NEXT therap*

#7 "bronchopulmonary hygiene"

#8 "tracheobronchial clearance"

#9 airway* NEXT clearance

#10 (chest* or lung* or sputum* or mucus*) NEAR3 (clearance*)

#11 "active cycle"

#12 ACBT

#13 deep NEXT breath*

#14 DBE

#15 "thoracic expansion"

#16 TEE

#17 sustained NEXT maximal NEXT inspirat*

#18 SMI

#19 breathing NEXT exercise*

#20 "postural drainage"

#21 "gravity assisted drainage"

#22 "gravity‐assisted drainage"

#23 "autogenic drainage"

#24 GAD

#25 CCPT

#26 ELTGOL

#27 FET

#28 "forced expiratory technique"

#29 huff*

#30 PEP

#31 PEEP

#32 resistance NEXT breath*

#33 "positive expiratory pressure"

#34 hi‐PEP

#35 bubble‐PEP

#36 bottle‐PEP

#37 oscillat*

#38 mouthpiece‐PEP

#39 pari‐PEP

#40 VRP1

#41 flutter*

#42 desitin

#43 cornet

#44 acapella

#45 scandipharm

#46 percuss*

#47 vibrat*

#48 vest

#49 HFCWO

#50 OHFO

#51 #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24 or #25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33 or #34 or #35 or #36 or #37 or #38 or #39 or #40 or #41 or #42 or #43 or #44 or #45 or #46 or #47 or #48 or #49 or #50

#52 #4 and #51

[Note: in search line #1, MISC1 denotes the field where the reference has been coded for condition, in this case, bronchiectasis]

Previous search (via Procite software)

physiotherap* or "physical therap*" or "bronchopulmonary hygiene" or "tracheobronchial clearance" or "airway* clearance" or "chest clearance" or "lung clearance" or "sputum clearance" or "mucus clearance" or "active cycle" or ACBT or "deep breath*" or DBE or "thoracic expansion" or TEE or "sustained maximal inspirat*" or SMI or "breathing exercise*" or "postural drainage" or "gravity assisted drainage" or "gravity‐assisted drainage" or "autogenic drainage" or GAD or CCPT or ELTGOL or FET or "forced expiratory technique*" or huff* or *PEP or PEEP or "resistance breath*" or "positive expiratory pressure" or "hi‐PEP" or "bubble‐PEP" or "bottle‐PEP" or "oscillat*‐PEP" or "mouthpiece‐PEP" or "pari‐PEP" or VRP1 or flutter or desitin or cornet or acapella or scandipharm or percuss* or vibrat* or vest or HFCWO or OHFO or "chest wall oscillat*" or "oral oscillat*" or "thoracic oscillat*".

[Limited to records coded as 'bronchiectasis']

Appendix 3. Search terms for PEDro (http://www.pedro.org.au/)

Bronchiectasis" or "Kartagener*" or "Agammaglobulinaemia"

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Stable bronchiectasis: high‐frequency chest wall oscillation ACT vs no ACT (control).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in HRQoL | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Change in FEV | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Change in FVC | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Change in TLC | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Change in RV | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6 Change in PaO2 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7 Change in PaCO2 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Change in breathlessness, cough and sputum | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Change in MMRC dyspnoea scale | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 2. Stable bronchiectasis: chest physiotherapy ACT vs no ACT (control).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in HRQoL | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Change in FEV1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Change in FVC | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Change in TLC | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Change in RV | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Change in PaO2 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Change in PaCO2 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Change in breathlessness, cough and sputum | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Change in MMRC dyspnoea scale | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Comparison 3. Stable bronchiectasis: PEP‐based ACTs vs no ACTs (control).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Sputum volume after 1 session | 1 | Mean Difference (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Figueiredo 2010.

| Methods | Randomised cross‐over trial Study setting: medical department, Brazil Study duration: 9 days |

|

| Participants | 8 people (mean age 47.4 years) with stable bronchiectasis productive of 47.8 mL sputum per day, diagnosed by HRCT (lobes affected or disease severity not stated), mean FEV1 65% predicted. Functional level not stated | |

| Interventions | Intervention: 1 session of oscillating PEP therapy using flutter, performed in seated position for 15 minutes' duration and 5 minutes' coughing after intervention Control: 1 session of sham oscillating PEP (using flutter valve without sphere or lid, with no modification of the size of the orifice). Same sequence of therapy applied 1‐Week washout period between interventions |

|

| Outcomes | Sputum volume (mL) Measurement was recorded immediately following completion of the intervention |

|

| Notes | No adverse events Funding: supported by Centers of Excellence Program (PRONEXFAPERJ), Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Financing for Studies and Projects (FINEP) and Rio de Janeiro State Research Supporting Foundation (FAPERJ) |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "This was a randomised, blinded and crossover study. Randomization defined the order of interventions in accordance with a computer‐generated sequence using a block size of 4" |