Abstract

Context:

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act increases healthcare access and includes provisions that directly impact access to and cost of evidence-based colorectal cancer screening. The Affordable Care Act’s removal of cost sharing for colorectal cancer screening as well as Medicaid Expansion have been hypothesized to increase screening and improve other health outcomes. However, since its passage in 2010, there is little consensus on the Affordable Care Act’s impact.

Evidence acquisition:

Data from March 2010 to June 2019 were reviewed and 21 relevant studies were identified; 19 studies examined CRC screening with the majority finding increased screening rates.

Evidence synthesis:

Eleven studies found significant increases, five found non-significant increases, three found non-significant decreases, and one study found a significant decrease in colorectal cancer screening. Three studies examined the impact on colorectal cancer incidence and stage of diagnosis, where a significant 2.4% increase in early diagnosis was found in one and a non-significant increase in incidence in another. However, survival improved after Medicaid expansion.

Conclusions:

Free preventive colorectal cancer screening and Medicaid expansion due to passage of the Affordable Care Act have been, in general, positively associated with modest improvements in screening rates across the country. Future studies are needed that investigate the longer-term impact of the Affordable Care Act on colorectal cancer morbidity and mortality rates, as screening is only the first step in treatment of cancerous and pre-cancerous lesions, preventing them from progressing. Moreover, more studies examining subpopulations are needed to better assess where gaps in care remain.

CONTEXT

In the U.S., colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death.1 This risk of high mortality can be significantly decreased by early screening. CRC screening can include colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, fecal occult blood tests (FOBTs), or fecal immunochemical tests. Annual FOBTs and sigmoidoscopies have been associated with a 33% significant decrease in mortality in 13 years for FOBT and a 43% significant decrease in 11 years for sigmoidoscopies.2,3 Moreover, colonoscopies can detect more neoplasms than sigmoidoscopies. According to a systematic review by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), all types of screening for CRC can decrease CRC incidence and mortality by 30%–60%.4

In March 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law with a few specific provisions hypothesized to influence CRC screening patterns.

Private insurance: The ACA’s essential benefits provide evidence-based preventive services at no cost to those with private health insurance. CRC screening is one of the preventive services covered with no cost sharing, beginning at age 50 years and continuing until age 75 years. Private insurance may be obtained through an employer or self-insured through the ACA Insurance Marketplace. All new insurance plans starting on September 23, 2010 must cover the ten essential benefits, whereas grandfathered plans, those insurance plans that began coverage prior to September 23, 2010, are not required to provide the ACA-mandated preventive services at no cost.

Medicare beneficiaries: Beginning on January 1, 2011, the ACA provides CRC screening at no cost to those on Medicare (aged ≥65 years) based on USPSTF recommendations.

Medicaid expansion: The ACA allowed states to opt into expanding Medicaid to cover all adults up to 138% of the federal poverty line beginning January 1, 2014, with some states adopting expansion earlier, some after 2014, and in 14 states, never. The majority of state Medicaid programs cover at least one of the CRC screening options, with more than half of states also offering CRC screening with no copayments.5

The ACA provisions followed CRC screening recommendations of the USPSTF, which are a colonoscopy every 10 years, a sigmoidoscopy every 5 years combined with a high-sensitivity FOBT every 3 years, or a FOBT annually starting at age 50 years.6 The USPSTF recommends that screenings should be determined by the patient and their primary care physician based on results and family history, with more frequent screening procedures covered for those with a family history. However, under the ACA, insurance beneficiaries still need to pay out of pocket for further testing or laboratory work after an initial positive test.

For those without insurance or on a high-deductible health insurance plan, the full cost of a colonoscopy can range from $1,000 to $5,000.7 Current trends have shown colonoscopies to be more commonly used over FOBTs or sigmoidoscopies despite the significantly lower cost of FOBTs.1 This trend is likely due to colonoscopies being used simultaneously as a screening and diagnostic procedure, as the ACA only covers screening.1

There have been many studies conducted on the cancer detection efficacy of the different types of CRC screening methods, as well as studies relating increased screening to decreased CRC incidence and mortality; however, there have been few studies focusing on the impact of the largest U.S. health reform law since the inception of Medicare and Medicaid on CRC screening, process outcomes, or mortality. In 2008, prior to the enactment of the ACA, only about 53% of U.S. men and women aged >50 years had been screened for CRC within the USPSTF’s recommended age and screening frequency guidelines.8 This systematic review summarizes the existing evidence among patients within the U.S. about the impact of the ACA on CRC screening rates, and what evidence, if any, exists concerning the impact of the ACA on CRC incidence and mortality rates.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

The literature search was conducted strictly using online databases. The search criteria required the literature be written in English and published after 2010, the year in which the ACA was passed. Studies were required to focus on the impact of the ACA, and not experimental studies or state laws that were passed prior to the ACA. The study must have involved CRC; thus, studies must have looked specifically at either colon or rectal cancer. No outcome was specified in the search, but the in-text search looked for outcome or behavior change that included screening, cost sharing, stage of cancer, morbidity, and mortality.

Data Sources

PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science were accessed through Harvard’s Countway Library of Medicine and Georgetown University’s Dahlgren Memorial Library. The search terms in these databases included Medical Subject Heading terms for both CRC and the ACA within the title and abstract. For the Embase search, the date was specified to be from 2010 to present. A list of full search terms can be found in the Appendix.

Study Selection

After completing the search on June 14, 2019, there were 116 results from PubMed, 142 results from Embase, and 112 results from Web of Science. From these, duplicates and conference abstracts were removed. The search results included advanced colorectal adenoma, abbreviated as ACA, and those were removed. Upon reading the title and abstract for relevance, publications that did not meet further selection criteria were excluded. Studies were excluded that inferred the possible impact of the ACA from similar state or foreign country health policies, examined pre-ACA time points only, examined non-ACA mandated state-level interventions, or provided neither CIs nor p-values. Policy analyses without regard to change in behavior or health outcomes, reviews of cancer guidelines, or individual case studies were also excluded. To be included, the study must have included a quantitative analysis with CRC screening, morbidity, or mortality as the primary study endpoint. Systematic reviews were excluded if they did not meet the aforementioned criteria. Only one systematic review that covered CRC screening rate changes satisfied the criteria, and its relevant studies were included in this review. Relevant references from the selected studies for review were also included.

Data Collection

Two researchers independently assessed inclusion of studies into the review and used the Guide to Community Preventive Services: Systematic Reviews and Evidence-Based Recommendations data abstraction form for data extraction from reports.9 The results were reconciled as a group with the senior author of this paper. Additional questions of clarification were e-mailed to the first author of each paper, allowing 2 weeks for a response before sending a follow-up e-mail. All questions were clarified.

The main outcomes of interest were change in prevalence, odds, or rate of screening or disease. Either a measure both before and after the ACA for comparison, or an estimate of the comparison itself was required. Any principal summary measure type was accepted. During data collection, both unadjusted and multivariable adjusted data that included at least age, sex, and race were recorded. Sub-analyses of interest included differences in screening rates or stage of disease by sex; race; SES, measured through education or income; and insurance status, including private, Medicare, and Medicaid. It was noted whether studies distinguished between grandfathered and non-grandfathered private insurance plans, as well as screening versus diagnostic colonoscopies. These categories of private insurance influence the amount of patient cost sharing for CRC screening. Specifically, those on grandfathered plans and those on high-deductible plans may still be subject to high out-of-pocket costs, a deterrent to screening. Individual state Medicaid expansion status was also an important factor to consider because states differed in whether they chose to expand their Medicaid services with federal aid. This could influence the affordability of, and access to, CRC screening.

Quality Assessment

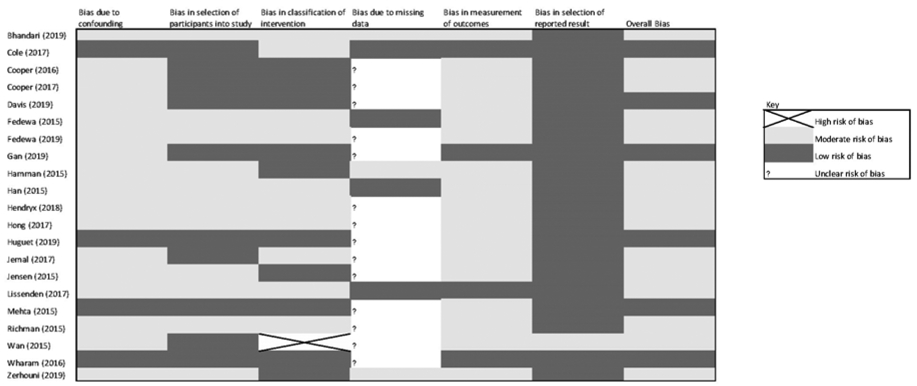

In assessing possible biases and limitations, two researchers independently reviewed the articles and used the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.10 Across categories of possible bias, studies were classified as having “low risk of bias,” “moderate risk of bias,” “high risk of bias,” or “not enough information given.” Risk of bias was evaluated by scoring for confounding, selection bias, intervention and outcome classification, missing data, and result selection. The overall bias summary measure was determined from an average of each category. Figure 2 reports the potential risk of bias for each of the studies included in this review.

Figure 2.

Estimated risk of bias.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

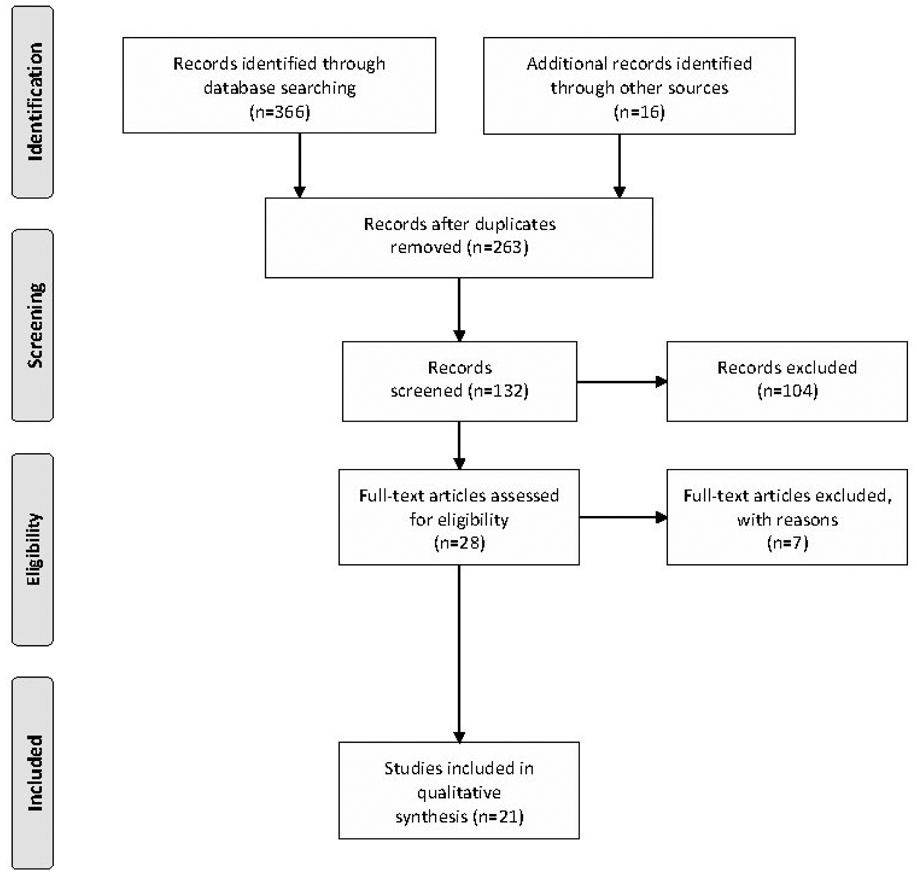

Figure 1 displays the process and selection of the final 21 articles that were included in this review. From the title and abstracts that met inclusion criteria, 89 articles were excluded because they were pre-policy studies, cross-sectional studies with no before–after comparison, policy briefs, meeting notes, case studies, review of guidelines, strategies, or frameworks for future consideration. Twenty-seven documents were read fully, and during the review, one additional article was found, resulting in 21 publications in total.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram: progression of article selection.

Appendix Table 1 provides key details of each of the 21 studies included in this review. These features include unit of analysis, study period, data source, study design, effect estimate, findings summaries, and limitations. Principal summary measures included percentage change, difference in difference, ORs, prevalence ratios, and rate changes.

Of the 21 papers, eight focused on the impact of Medicaid expansion, and the other 13 focused on the effects of the removal of cost sharing on CRC screening. Among those 13, three examined how changes in cost sharing impacted those with private insurance, four focused on Medicare-only beneficiaries, five studied both private and Medicare beneficiaries, and one investigated those served by rural health clinics. Five studies used the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey, four used the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), and one used the National Health Interview Survey. Two other studies analyzed commercial health insurance claims data, and another four studies used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid claims data. The Health Resources and Services Administration’s Uniform Data System was used by one study. Four studies used either a hospital, state, or national registry. Nineteen of 21 studies examined the impact of the ACA on changes in CRC screening rates. About half of the studies examined changes in colonoscopy rates only, whereas the others looked at all forms of CRC screening.

Morbidity, Mortality, and Survival

Of the 21 studies, three studies11-13 examined morbidity and survival: Two focused on the stage of cancer diagnosis, whereas the other looked at screening, stage, and survival post-diagnosis. In the only paper to track survival post-diagnosis, Gan et al.11 examined the role of Medicaid expansion in Kentucky via hospital databases, cancer registry, and death certificates. The study found increased CRC screening rates, no difference in incidence rates, and an improved CRC survival post-diagnosis. Although CRC incidence remained stable, the prevalence of early-stage cancer increased from 4.7% to 7.6% of all CRC diagnoses, whereas later-stage cancer decreased from 8.2% to 7.4%. That same study described significant survival improvements post-Medicaid expansion among those on Medicaid diagnosed with CRC in Kentucky (hazard ratio=0.73). Lissenden and colleagues12 utilized the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer registry and found a significant 8% increase in early stage CRC diagnoses. In their subgroup analyses, they found an increased early diagnosis of 3.8% for men and 12.8% for women.12 They also found a non-significant decrease of 2.2% in the overall number of late-stage diagnoses, but with a significant decrease among men (–10.3%).12 The analysis of stage at diagnosis conducted by Jemal et al.13 utilized the National Cancer Database and found no difference in the percentage of early-stage versus late-stage CRC diagnoses. However, Lissenden and colleagues12 categorized Stage I and II tumors as early stage, whereas Jemal et al.13 categorized only Stage I as early stage. No study evaluated the impact of the ACA on CRC mortality rates.

Screening

The other 19 studies sought to find evidence of health behavior change through CRC screening uptake. Of studies investigating CRC screening rates, 11 found significant increases, four found non-significant increases, three found non-significant decreases, and one found a significant decrease.

Of the 11 studies that found significant increases in CRC screening rates, four were classified as having low risk of bias. Wharam and colleagues14 utilized private insurance claims data and found that the ACA was associated with a significant 9.1% increase in CRC screening uptake among United Healthcare’s beneficiaries. Huguet et al.15 focused on Medicaid expansion and reported an adjusted OR of 1.76 (95% CI=1.41, 2.18) of FOBT/fecal immunochemical testing rates in expansion states before and after the ACA. One study specifically looked at the implementation of Accountable Care Organizations and found annual increases in CRC screening when compared with pre-ACA rates, with 2014 having nearly double the change than 2011.16 The study by Gan and colleagues11 of screening, incidence, and post-diagnosis survival, also classified as low risk of bias, found that CRC screening post-ACA nearly tripled compared with pre-ACA among Medicaid enrollees.

The other articles that found significant increases in screening utilized survey and claims data. Wan et al.17 found a significant 3.74% increase in CRC screening after the elimination of cost sharing. A study in the National Health Interview Survey also found a significant 3.9% increase in CRC screening.18 This study found the most significant increases in screening among low- and middle-income Medicare patients.18 Another study found that CRC screening increased for both those on private insurance and Medicare.19 Four studies utilized the BRFSS: One focused on the elimination of cost sharing and three focused on the impact of Medicaid expansion. The BRFSS study supported the findings of the previous study in that low-income Medicare patients experienced the biggest increases in CRC screening with the elimination of cost sharing, but the increase was significant only among men.20 The three other studies that utilized the BRFSS all found significant increases in CRC screening after ACA-mandated Medicaid expansion in states that expanded prior to 2014 compared with non-expansion states.21-23

Four other studies found non-significant increases in CRC screening rates24-27 and two of these were classified as having a low risk of bias.24,25 Mehta and colleagues24 used private insurance claims data and found a non-significant 3.1% increase in colonoscopy screening rates among those with non-grandfathered plans compared to grandfathered plans post-policy. Cole et al.25 also classified as having low risk of bias, found a non-significant 1.9% increase in CRC screening among states that expanded Medicaid compared to those states that did not expand. Finally, both Richman and colleagues26 and Hong et al.27 utilized Medical Expenditures Panel Survey data to estimate changes in CRC screening before and after the ACA. One study found that only older individuals aged 65–75 years benefited from the policy,26 whereas the other found that younger individuals aged 50–64 years had a 1.4% increase in screening rates.27

Four studies found decreases in CRC screening after implementation of the ACA, one of which was significant. Although Cooper and colleagues28 in 2016 found no significant changes in colonoscopy use among the entire Medicare population, approximately 4% significant decreased odds of colonoscopy screening was found among those in the bottom three quartiles of income after the passing of the ACA compared with before.29 This result was unexpected as, theoretically, the ACA would be expected to preferentially increase access to care for low-income w.30 Cooper et al.29 acknowledged the unexpected findings and suggested these results may be attributed to their examination of high-risk individuals who already had little cost sharing for CRC screenings since 2001 when Medicare began covering colonoscopies for those that subpopulation. This finding is inconsistent with the results from other studies included in this review that examined the elimination of cost sharing on CRC screening. Three studies that examined income found that the biggest increases in screening occurred among low-income individuals.18,20,26 Both Han and colleagues31 and Jensen et al.32 found overall rates of any CRC screening decreased non-significantly from before to after elimination of cost sharing. However, in the Medicare subgroup, significant decreases in FOBT use among those on Medicare Advantage (managed care) and also in endoscopy use among those who are Dual Eligible were reported,32 perhaps reflecting a trade-off between FOBT use and colonoscopy utilization rates: Patients may use more expensive procedures when covered by insurance.

Risk of Bias

No study included in this review had an overall “high risk of bias.” The five studies that were classified with low risk of bias were given the rating because of their use of control groups, non-survey data, validated data sets, and extensive methodology and statistical analysis to account for confounding factors. However, most studies were classified as having “moderate risk of bias” (Figure 2). This rating for the majority of these studies was attributed to the possible bias due to the lack of concurrent control group in before–after designs, as this design cannot account for time-related trends in CRC screening rates not attributable to the introduction of the ACA. Survey and non-validated claims data are not able to distinguish beneficiaries on grandfathered, still responsible for cost sharing, or non-grandfathered private health insurance plans. Papers that examined the role of Medicare expansion used 2014 as their cut off year, with some studies not adequately considering differences between states that expanded Medicaid at different times either before or after 2014. Another study possibly misclassified the intervention by making the assumption that all people aged ≥65 years were covered by Medicare, and all people aged <65 years only had private insurance.12 Random misclassification such as this likely resulted in an underestimate of the beneficial effects of the ACA on the stage of CRC diagnosis.33

The reliance on large, cross-sectional survey data in many of the studies may also cause outcome misclassification. These surveys do not focus on CRC, but rather offer a plethora of data on respondents’ overall health and behavior; for example,31 CRC screening was of secondary interest. Although these surveys have provided insight on how the ACA has impacted the lives of many people of all age ranges, the self-reported data and lack of focus on CRC screening may have introduced bias due to outcome misclassification, which would likely lead to an underestimation of the impact.

Another source of outcome misclassification stems from the inability of surveys and claims data to accurately distinguish screening versus diagnostic CRC procedures. The ACA only mandates that health insurance plans fully cover CRC screening procedures, whereas diagnostic CRC procedures are still subject to cost sharing. Thus, diagnostic procedure rates are not expected to change after the passage of the ACA. Grouping diagnostic and screening procedures together in analysis would likely bias the results towards the null. Fourteen of 21 studies could not adequately distinguish between screening and diagnostic procedures that were reported.

Studies that focus on different populations or different insurance coverage groups can be difficult to compare. Variability in the results among publications may stem from the age range of those impacted by the ACA CRC screening provision (50–75 years), as people aged 50–64 years are more likely to be on private insurance, whereas the majority of those aged ≥65 years are on Medicare. Although some studies focused on one insurance group, others looked at both groups.

Lastly, it was difficult to evaluate bias resulting from missing data due to limited reporting of the magnitude or type of missing data. In most studies, missing data from surveys were excluded and a complete case analysis was used.

Limitations

A major limitation of these analyses is the complexity of the ACA: Multiple changes in policy occurred in addition to removal of cost sharing. Although these studies may attribute changes from pre/post ACA to only the removal of cost sharing or only the expansion of Medicaid, these inferences often did not take into account other aspects of the ACA or state law that may have contributed to these changes. The observed changes in CRC screening rates could be due, at least in part, to background secular trends unrelated to the ACA, such as the provision of other free preventive services, changes in health provider incentives, state variability in promotion of the ACA, and other benefits of increased access to insurance coverage. It should be noted that the difference-in-difference design aims to control for these background trends, specified or unspecified. Though it can be difficult to assimilate results across various real-world studies, it is important to include all studies assessing the various components of the ACA, as only reporting one aspect of the ACA would not capture all other influences on CRC screening, morbidity, and mortality.

Moreover, many of the earlier studies focused on the removal of cost sharing in 2010, whereas more recent studies have examined the impact of Medicaid expansion in 2014. The presence of many non-significant but positive results in earlier publications could be due to the ACA tackling only one dimension of CRC preventive care. The policy focuses exclusively on easing the cost of the screening procedure, which is one major barrier to CRC screening.33 As the ACA removes cost of screening as an obstacle, many policy analyses predicted screening would increase. However, there are many other factors that contribute to why people may get screened, such as fear, healthcare access, and inconvenience.34 Moreover, a previous study looking at patient knowledge of their health plan and out-of-pocket costs found that 35% of patients knew the amount of their insurance deductible, but only 5% of patients could correctly identify all the covered services.35 This shows the limited knowledge patients already have about their health insurance; thus, changes in services covered by the ACA may not be well known by patients. With multiple factors coalescing to impact healthcare utilization, it may be difficult to attribute the elimination of cost sharing of CRC screenings as the sole or primary cause of the significant changes in CRC screening. However, the best-designed studies suggest that some changes in screening can be reasonably attributed to the ACA. The more recent studies that focused on Medicaid expansion, another facet of the ACA, have shown consistently positive results over time. This supports the idea that a multifaceted approach to increase screening is necessary to make more consistent, significant change. Another area of interest that should be explored in future studies should be examining specific subpopulations. Studies included in this review were heterogeneous in their subgroups of interest, making it difficult to find conclusive results regarding one race or income group. This is especially pertinent given the possible changes to the ACA under future government administrations. Finally, only one study examined the impact of the ACA on CRC incidence and mortality.

The largest limitation of these studies is the short follow-up after the passage of the ACA, leading to a lack of statistical power to detect moderate benefits. The time of post-ACA analysis ranged from 9 months to 2 years. Patient behavior may take longer to fully adapt to the change in policy, especially as the screening interval between testing eligibility lasts 3–10 years for many of the testing options. Additionally, long-term health outcomes such as morbidity and mortality would need even further extended years of follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first systematic review that examines the ACA’s impact on CRC screening behaviors and outcomes. A few patterns emerged. Overall, CRC screening in any form has increased modestly across the nation since passage of the ACA. Specifically, colonoscopy rates are increasing, whereas sigmoidoscopy and FOBT rates are either holding steady or slightly decreasing. Four of five studies with the lowest risk of bias reported significant increases in CRC screening. The ACA seems to have had the biggest impact on older, lower-SES populations.11,17,18,20,26,31,32 This may be due to the fact that lower-SES groups would have previously experienced the greatest cost barriers to screening prior to the passing of the ACA. In addition, black and Hispanic populations experienced greater increases in CRC screening when compared with Caucasians, 15,19,23,28,31 suggesting that improved access and decreased cost to care through the ACA has helped minority populations.

These studies and this review also provide a foundation for future research to better estimate the effect of the ACA on CRC incidence and mortality across longer follow-up periods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported by grant DP1ES025459 from the NIH Pioneer Award Program, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland.

None of the funding sources had any role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation, or write-up of the data.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9726): 1624–1633. 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60551-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. https://doi.Org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood: Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(19): 1365–1371. 10.1056/nejm199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 149(9): 638–658. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Coverage of Preventive Services for Adults in Medicaid - Survey Findings, www.kff.org/report-section/coverage-of-preventive-services-for-adults-in-medicaid-survey-findings/. Published 2014. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 6.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Update Summary: Colorectal Cancer: Screening – U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/colorectal-cancer-screening. Published 2008. Accessed December 2, 2019.

- 7.Aliferis L. How Much Does A Colonoscopy Cost In California? Help Find Out. www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/05/28/410074906/how-much-does-a-colonoscopy-cost-in-california-help-find-out NPR; Published May 28, 2015. Accessed December 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2011–2013. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures/colorectal-cancer-facts-and-figures-2011-2013.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed December 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaza S, Wright-De Agüero LK, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000; 18(1):44–74. 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins J. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1. 0. The Cochrane Collaboration, https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/. Updated 2011. Accessed December 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan T, Sinner HF, Walling SC, et al. Impact of the Affordable Care Act on colorectal cancer screening, incidence, and survival in Kentucky. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228(4):342–353.e1. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lissenden B, Yao NA. Affordable Care Act changes to Medicare led to increased diagnoses of early-stage colorectal cancer among seniors. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1): 101–107. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, Han X. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3906–3915. 10.1200/jco.2017.73.7817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wharam JF, Zhang F, Landon BE, LeCates R, Soumerai S, Ross-Degnan D. Colorectal cancer screening in a nationwide high-deductible health plan before and after the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2016;54(5):466–473. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huguet N, Angier H, Rdesinski R, et al. Cervical and colorectal cancer screening prevalence before and after Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. Prev Med. 2019;124:91–97. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MM, Shafer P, Renfro S, et al. Does a transition to accountable care in Medicaid shift the modality of colorectal cancer testing? BMC Health Serv Res. 2019; 19:54 10.1186/s12913-018-3864-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan TT, Ortiz J, Berzon R, Lin Y-L. Variations in colorectal cancer screening of Medicare beneficiaries served by rural health clinics. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2015;2 10.1177/2333392815597221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fedewa SA, Goodman M, Flanders WD, et al. Elimination of cost-sharing and receipt of screening for colorectal and breast cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3272–3280. 10.1002/cncr.29494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhandari NR, Li C. Impact of the Affordable Care Act’s elimination of cost-sharing on the guideline-concordant utilization of cancer preventive screenings in the United States using Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Healthcare (Basel). 2019;7(1):36 10.3390/healthcare7010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamman MK, Kapinos KA. Mandated coverage of preventive care and reduction in disparities: evidence from colorectal cancer screening. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 3):S508–S516. 10.2105/ajph.2015.302578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedewa SA, Yabroff KR, Smith RA, Goding Sauer A, Han X, Jemal A. Changes in breast and colorectal cancer screening after Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):3–12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendryx M, Luo J. Increased cancer screening for low-income adults under the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. Med Care. 2018;56(11):944–949. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zerhouni YA, Trinh Q-D, Lipsitz S, et al. Effect of Medicaid expansion on colorectal cancer screening rates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(1):97–103. 10.1097/dcr.0000000000001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta SJ, Polsky D, Zhu J, et al. ACA-mandated elimination of cost sharing for preventive screening has had limited early impact. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(7): 511–517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole MB, Galarraga O, Wilson IB, Wright B, Trivedi AN. At federally funded health centers, medicaid expansion was associated with improved quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):40–48. 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richman I, Asch SM, Bhattacharya J, Owens DK. Colorectal cancer screening in the era of the Affordable Care Act. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):315–320. 10.1007/s11606-015-3504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong Y-R, Jo A, Mainous AG. Up-to-date on preventive care services under Affordable Care Act: a trend analysis from MEPS 2007–2014. Med Care. 2017;55(8):771–780. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Schluchter MD, Dor A, Koroukian SM. Changes in receipt of cancer screening in Medicare beneficiaries following the Affordable Care Act. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):djv374 10.1093/jnci/djv374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper GS, Kou TD, Dor A, Koroukian SM, Schluchter MD. Cancer preventive services, socioeconomic status, and the Affordable Care Act. Cancer. 2017;123(9): 1585–1589. 10.1002/cncr.30476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kominski GF, Nonzee NJ, Sorensen A. The Affordable Care Act’s impacts on access to insurance and health care for low-income populations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:489–505. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han X, Yabroff KR, Guy GP Jr, Zheng Z, Jemal A. Has recommended preventive service use increased after elimination of cost-sharing as part of the Affordable Care Act in the United States? Prev Med. 2015;78:85–91. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen GA, Salloum RG, Hu J, Ferdows NB, Tarraf W. A slow start: use of preventive services among seniors following the Affordable Care Act’s enhancement of Medicare benefits in the U.S. Prev Med. 2015;76:37–42. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bross I. Misclassification in 2 x 2 tables. Biometrics. 1954;10(4):478–486. 10.2307/3001619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones RM, Devers KJ, Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):508–516. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed M, Fung V, Price M, et al. High-deductible health insurance plans: efforts to sharpen a blunt instrument. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):1145–1154. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.