What appears to be the first cohort study to follow intensive care unit (ICU) patients beyond hospital discharge was published in 1976 (1). A year after ICU admission, 73% of patients had died, 23% were at home, and 10 were still hospitalized. Like all scientists in a novel field, the authors of this study lacked a vocabulary for measuring their observations. They categorized survivors as “fully recovered,” “progressing to full recovery,” “partial recovery at best,” and having “no improvement from time of discharge,” but they never defined these terms.

Since that first study, more than 425 peer-reviewed papers have reported on the physical, cognitive, and mental health or quality of life of ICU survivors (2). The field has matured and developed terminology, such as post intensive care syndrome (3, 4), and research tools, such as core outcome measurement sets (5). Prospective studies have illuminated the persistent, and sometimes permanent, physical, cognitive, and mental health impairments experienced by ICU survivors (6–12). And funders like the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and professional societies have declared improving long-term quality of life (QoL) for acute illness survivors to be a research priority (3, 13–16).

But so far, our collective work and enthusiasm have not improved QoL for ICU survivors. A 2018 Cochrane Systematic Review of follow-up services aimed at improving long-term outcomes of ICU survivors found no evidence that they improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (17). This year, a systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors found that QoL was assessed more often than any other outcome (18). But in meta-analysis, exercise and physical rehabilitation programs, follow-up services, and psychosocial programs were not associated with improved QoL among survivors (18). Although absence of evidence does not mean such follow-up services conclusively do not work, the early results have not been promising. And yet, a growing number of academic hospitals are exploring opening specialty ICU survivor outpatient clinics offering exactly these sorts of interventions (19–22).

It is time to pause, review definitions, and reexamine our assumptions. In this essay, we first review how QoL is defined and measured and argue that assumptions about the relationship between functional recovery and QoL need to be empirically tested. Next, we review how QoL normally evolves after a change in health state and discuss how research into psychological adaptation during survivorship could help make future randomized trials more efficient. Finally, we propose that ICU providers are in a unique and powerful position to improve QoL by shaping patient and family expectations about survivorship.

Definitions: What We Talk about When We Talk about Quality of Life

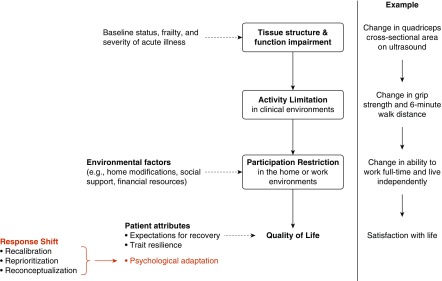

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (23). This definition reflects that QoL is a subjective self-evaluation made by an individual—not a static or objective measure bestowed on that individual. The WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework (24) describes how physiological impairments can limit a person’s physical and cognitive abilities and restrict their ability to participate in usual activities of their home and work environments. Conceptual models of ICU survivorship extend the ICF to include QoL as a hypothesized outcome of participation restrictions (25) (Figure 1). Another framework proposed by Wilson and Cleary (26, 27) uses domains called biology and physiology, symptoms, functional status, health perception, and quality of life, but maintains that an individual’s QoL is strongly determined by their ability to perform valued tasks (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). Importantly, both frameworks assume that illness limits what people can do independently, and these limitations make people feel worse about their lives. This assumption is intuitive for most people (25, 28), but it needs to be rigorously tested. A study of more than 1,400 ICU survivors 1 year after discharge found that only mental health symptoms, not physical or cognitive functioning, were associated with whether survivors rated their current health state as acceptable (29).

Figure 1.

The relationship between the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (WHO ICF) framework, patient-reported quality of life, and response shift among intensive care unit survivors. Boxes contain WHO ICF domains. Dashed lines indicate modifying factors.

HRQoL is a related, but separate, term. According to the International Society for Quality of Life Research, HRQoL assesses “people’s level of ability, daily functioning, and ability to experience a fulfilling life” (30). In short, HRQoL measures ask: “Can you?” and QoL measures ask: “Do you care?” The nebulous link between what a person can do independently and their subjective well-being makes it essential for investigators to be specific about what we are measuring. For example, the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical component summary score is sometimes (mistakenly) called a QoL measure. The 10 questions in the physical component summary score ask if the respondent is limited in their ability to perform a series of physical actions, including walking, climbing stairs, bathing, carrying groceries, and working. But under the ICF framework, these are questions about participation restrictions, not QoL. In comparison, the WHO Quality of Life–BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) instrument (31) includes fundamentally different questions about the same activities, including “How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities?” and “How satisfied are you with your capacity for work?” The WHOQOL-BREF questions capture an individual’s subjective perceptions in relation to their personal goals, expectations, and culture and apply to everyone regardless of whether they value carrying groceries. It is a measure of QoL.

To be clear, we are not advocating that clinical researchers stop using well-validated instruments like SF-36 or EQ-5D, especially because both instruments are core outcome measures for clinical research on survivors of acute respiratory failure (5). Rather, we are encouraging researchers to think critically and speak carefully about what these instruments are measuring, to purposefully measure what ICU survivors can do, and to measure QoL by using instruments that ask survivors for their subjective perception of their position in life. Doing so will facilitate comparisons with previous studies and generate data for exploring the relationship between HRQoL and QoL.

Response Shift: Are Trials Failing Because Survivors Are Succeeding?

Over time, ICU survivors may adapt to new impairments and report improvements in QoL that are not explained by changes in their physical or cognitive function. This phenomenon is known as “response shift,” (32, 33) a term that encompasses forms of psychological adaptation, including recalibration, reprioritization, and reconceptualization, that complicate the relationship between participation restriction and QoL (Figure 1). This phenomenon has been documented in patients with stroke (34), spinal cord injury (35), cancer (36), multiple sclerosis, and inflammatory bowel disease (37). Table 1 provides an example of response shift in a survivor of acute critical illness.

Table 1.

Illustration of positive response shift in an intensive care unit survivor

| Case: Janice is a 58-yr-old woman with hypertension who developed pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. She was mechanically ventilated for 6 d and spent 2 wk in acute rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Before her hospitalization, she worked full time as a media relations specialist and was very physically active, jogging or swimming almost daily. Six months later she is no longer working, cannot run a mile, has short-term memory impairment, and reports that she is consistently too fatigued in the afternoon to go out for dinner or participate in evening social events. Despite these changes, she reports no change in her quality of life compared to before her illness. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Form of Response Shift | Definition | Janice’s Description in Conversation |

| Recalibration | A change in a person’s internal standards | “I walk a couple miles with my neighbor and her dog most days—as long as the weather’s good—and I’ve started doing yoga on Tuesday mornings. I’m very conscious of what I eat, too. That’s pretty good for someone nearing 60.” |

| Reprioritization | A change in personal values | “Being sick made me think about how I want to spend my time. The way friends and family rallied around me was just incredible. I decided I wouldn’t go back to work—retire early—even before I left the ICU. Next month I’m meeting childhood friends in Florida for a mini-reunion, and I’m going to my niece’s graduation in May. That’s the good stuff.” |

| Reconceptualization | A change in how quality of life is defined | “Last month I started volunteering at a women’s shelter, and some of these women, they’re handling so much, trying to keep their kids safe, to keep custody of them, find housing, work, everything… every time I’m there it drives home again just how lucky I am.” |

Definition of abbreviation: ICU = intensive care unit.

Unfortunately, response shift is also sometimes treated as a measurement problem (38–40). Researchers in this camp see patient-reported QoL after adaptation as biased and seek to estimate a patient’s “true” unbiased QoL. From a statistical perspective, the measurement error approach treats patient-reported QoL as the sum of true quality of life (a latent variable) and an error term created by the patient’s psychological adaptation. We posit that the “true QoL” in the following equation is the QoL healthy people expect survivors to report: True QoL + Response Shift = Patient-reported QoL. Researchers advocating for this definition seek to estimate the response a patient would have given in a counterfactual world without psychological adaptation. The disparity between the expectations of healthy survivors and the reports of actual survivors stems from the disability paradox, whereby people experiencing chronic illness and disability are happier (on average) than healthy people predict they would be themselves under similar circumstances (41).

We discourage treating response shift as a form of measurement error, because doing so makes “true” QoL an objective value defined by an external observer, rather than by the survivor. We believe that each person must be empowered to define their own QoL. Therefore, we endorse the following model of response shift, which centers survivor perceptions: Physical Health + Response Shift = Patient-reported QoL = True QoL. One hypothesis about why previous trials of interventions to improve ICU survivors’ QoL failed is that substantial proportions of patients in both the treatment and control groups of these trials may have experienced positive response shift. These survivors are analogous to patients with preexisting immunity in a trial of disease prevention. Enrolling these immune individuals, who will adapt and thrive regardless of interventions, decreases a study’s power to detect existing effects (42). Studying adaptation in survivorship and identifying patient characteristics associated with response shift could help create more efficient clinical trials (43). A better understanding of trends in response shift would enable investigators to enroll ICU survivors who are least likely to report improvement in QoL (e.g., because of positive response shift) and instead focus on recruiting those survivors most likely to benefit from the study intervention.

Expectations: It’s Okay to Not Feel Okay

If we accept that true QoL is a survivor’s subjective perception, interventions to improve QoL should target expectations as well as psychological adaptation and physical and cognitive function. Research on the relationship between expectations and patient-reported outcomes draws heavily from marketing research on consumer satisfaction (44). Expectancy-discrepancy theory proposes that people are satisfied when outcomes meet or exceed their expectations and dissatisfied when expectations go unfulfilled (45, 46). Under assimilation-contrast theory (47), we evaluate outcomes using expectancy-discrepancy when the difference between expectations and reality is wide, but when outcomes are close to our expectations we revise our expectations to fit the truth.

Research on satisfaction with surgical procedures suggests these theories hold up in the context of high-stakes healthcare decisions (48). But satisfaction with provided health care is not the same as satisfaction with one’s “position in life in the context of the culture and value systems” (23). To move the needle on QoL, we should try talking to survivors about what their lives are likely to be like after discharge (49). Failing to do so in a standardized way may have contributed to the failure of previous trials if the intervention group had greater expectations for functional recovery. It is nearly impossible to blind ICU survivors to rehabilitation interventions. If survivors randomized to the intervention versus control group have higher expectations for their recovery, these survivors may be less likely to adapt to functional impairments and more likely to perceive their health and QoL as poor. Providing standard information to all enrolled patients regarding expected recovery trajectories might help create more comparable intervention and control groups.

There are more important reasons to set appropriate expectations than study design, though. Discussing possible outcomes is an essential part of ensuring patient safety after discharge. Although the focus of the critical care practitioner is, understandably, to ensure patients are physiologically suitable for discharge, waiting for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress to become obvious puts survivors at risk. Patients and their families leaving the hospital need to be debriefed and prepared before they are discharged. As author M.S.H., an ICU survivor, notes: “Unprepared survivors may suffer in silence if they’ve absorbed the message that feeling physically better should be ‘enough.’ This sentiment can lead to self-isolation, substance abuse, a delay in seeking treatment (if they ever do), and at worst suicide.”

Of course, it is very hard to predict how any individual will recover, and we are not advocating discouraging patients. But we are also not advocating unbridled optimism. Instead, we recommend disclosing and normalizing that previously healthy individuals may experience new long-lasting impairments through no fault of their own, regardless of participation in rehabilitation. This does not mean that patients are helpless. In fact, they have significant control over how they respond to the uncertainty before them. In short, we recommend honesty.

Research on aging provides clues about why awareness of the potential for future health impairments may be protective. A recent longitudinal study of community-dwelling adults in their 70s, 80s, and 90s found that adults who predicted (correctly) at enrollment that their health would decline, termed “realistic pessimism,” not only reported few symptoms of depression but lived longer than the elders who were incorrectly optimistic about their health (50). One hypothesis about the mechanism driving this association is that the realists are more likely to take preemptive actions that permitted healthy aging in place, including accessing preventative care, living near family members, and seeking in-home assistance. Disclosing and normalizing the experiences of ICU survivorship may foster similar adaptive behaviors.

Consider two survivors: one assuming a return to their baseline status and one who is fully aware that their recovery may be incomplete. When both find they have significantly less stamina despite completing all prescribed rehabilitation, how do they react? The survivor who assumed complete recovery is likely to feel disappointed, and they may feel betrayed or like they have failed their doctors. They are also unlikely to have secured long-term, logistical support. The patient who knew that recovery was uncertain is not surprised. They may even face adapting to their fatigue with a sense of determination and grit. The prepared survivor is also more likely to have marshalled community or financial resources and fostered relationships with friends and family who can provide long-term support. Although some people worry that informed survivors will be discouraged and less likely to adhere to prescribed rehabilitation, data suggest the opposite. Karnatovskaia and colleagues found that patients identified as having depressive, anxiety, and cognitive symptoms at ICU discharge were significantly more likely to participate in follow-up 3 months after hospital discharge (51). Furthermore, patients with pulmonary conditions and congestive heart failure who were informed of cognitive screening results before discharge had fewer readmissions and increased adherence to medical recommendations (52).

Disclosing uncertainty and fostering realistic expectations may seem counterintuitive. Self-help books like The Power of Positive Thinking (53), which preach positive affirmations and unrelenting optimism, have sold well in the United States for more than six decades. But honesty and bravely facing our uncertain futures are simple and inexpensive to try. Given our meager progress improving QoL for ICU survivors to date, the price of continuing to do the same things is no longer affordable.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants K01HL141637 (A.E.T.), K23HL138206 (A.M.P.), and T32HL007534-37 (I.M.O.).

Author Contributions: A.E.T. and M.S.H. drafted the article. M.S.H., I.M.O., M.M.H. and A.M.P. provided critical revisions for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Cullen DJ, Ferrara LC, Briggs BA, Walker PF, Gilbert J. Survival, hospitalization charges and follow-up results in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604292941805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, Nasser MF, Venna VR, Lolitha R, et al. Outcome measurement in ICU survivorship research from 1970 to 2013: a scoping review of 425 publications. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1267–1277. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, Hopkins RO, Weinert C, Wunsch H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:502–509. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott D, Davidson JE, Harvey MA, Bemis-Dougherty A, Hopkins RO, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Exploring the scope of post-intensive care syndrome therapy and care: engagement of non-critical care providers and survivors in a second stakeholders meeting. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:2518–2526. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Friedman LA, Bingham CO, III, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. an international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1122–1130. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, et al. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D, Parkinson RB, Chan KJ, Orme JF., Jr Two-year cognitive, emotional, and quality-of-life outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:340–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-763OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen ME, Christie JD, Lanken PN, Biester RC, Thompson BT, Bellamy SL, et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1307–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2025OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1306–1316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, Jackson JC, Hough CL, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. NIH NHLBI ARDS Network. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:567–576. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamdar BB, Sepulveda KA, Chong A, Lord RK, Dinglas VD, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Return to work and lost earnings after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year prospective, longitudinal study of long-term survivors. Thorax. 2018;73:125–133. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, Curtis JR, Gajic O, Guyatt G, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1121–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieu TA, Au D, Krishnan JA, Moss M, Selker H, Harabin A, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Research in Lung Diseases Workshop Panel. Comparative effectiveness research in lung diseases and sleep disorders: recommendations from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:848–856. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0634WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson SS, Goss CH, Patel SR, Anzueto A, Au DH, Elborn S, et al. American Thoracic Society Comparative Effectiveness Research Working Group. An official American Thoracic Society research statement: comparative effectiveness research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1253–1261. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1790ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutschman CS, Ahrens T, Cairns CB, Sessler CN, Parsons PE Critical Care Societies Collaborative/USCIITG Task Force on Critical Care Research. Multisociety task force for critical care research: key issues and recommendations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:96–102. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1848ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schofield-Robinson OJ, Lewis SR, Smith AF, McPeake J, Alderson P. Follow-up services for improving long-term outcomes in intensive care unit (ICU) survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD012701. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012701.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geense WW, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, Vermeulen H, Hannink G, Zegers M. Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1607–1618. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasiter S, Oles SK, Mundell J, London S, Khan B. Critical care follow-up clinics: a scoping review of interventions and outcomes. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016;30:227–237. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jensen JF, Egerod I, Bestle MH, Christensen DF, Elklit A, Hansen RL, et al. A recovery program to improve quality of life, sense of coherence and psychological health in ICU survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial, the RAPIT study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1733–1743. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sevin CM, Bloom SL, Jackson JC, Wang L, Ely EW, Stollings JL. Comprehensive care of ICU survivors: Development and implementation of an ICU recovery center. J Crit Care. 2018;46:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bienvenu OJ. What do we know about preventing or mitigating postintensive care syndrome? Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1671–1672. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: rationale and current status. Int J Ment Health. 1994;23:24–56. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G. The burdens of survivorship: an approach to thinking about long-term outcomes after critical illness. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:327–338. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: a conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brummel NE. Measuring outcomes after critical illness. Crit Care Clin. 2018;34:515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerckhoffs MC, Kosasi FFL, Soliman IW, van Delden JJM, Cremer OL, de Lange DW, et al. Determinants of self-reported unacceptable outcome of intensive care treatment 1 year after discharge. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:806–814. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05583-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ISOQOL. What is QOL? 2019 [accessed 2019 Oct 20] Available from: https://www.isoqol.org/what-is-qol/

- 31.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sprangers MA, Schwartz CE. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oort FJ, Visser MRM, Sprangers MAG. Formal definitions of measurement bias and explanation bias clarify measurement and conceptual perspectives on response shift. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1126–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barclay R, Tate RB. Response shift recalibration and reprioritization in health-related quality of life was identified prospectively in older men with and without stroke. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Leeuwen CMC, Post MWM, van der Woude LHV, de Groot S, Smit C, van Kuppevelt D, et al. Changes in life satisfaction in persons with spinal cord injury during and after inpatient rehabilitation: adaptation or measurement bias? Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1499–1508. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamidou Z, Dabakuyo-Yonli TS, Guillemin F, Conroy T, Velten M, Jolly D, et al. Impact of response shift on time to deterioration in quality of life scores in breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lix LM, Chan EK, Sawatzky R, Sajobi TT, Liu J, Hopman W, Mayo N. Response shift and disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1751–1760. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1188-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ubel PA, Loewenstein G, Jepson C. Whose quality of life? A commentary exploring discrepancies between health state evaluations of patients and the general public. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:599–607. doi: 10.1023/a:1025119931010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ubel PA, Peeters Y, Smith D. Abandoning the language of “response shift”: a plea for conceptual clarity in distinguishing scale recalibration from true changes in quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:465–471. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9592-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ubel PA, Smith DM. Why should changing the bathwater have to harm the baby? Qual Life Res. 2010;19:481–482. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ubel PA, Loewenstein G, Schwarz N, Smith D. Misimagining the unimaginable: the disability paradox and health care decision making. Health Psychol. 2005;24:S57–S62. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon R, Maitournam A. Evaluating the efficiency of targeted designs for randomized clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6759–6763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boessen R, Heerspink HJL, De Zeeuw D, Grobbee DE, Groenwold RH, Roes KC. Improving clinical trial efficiency by biomarker-guided patient selection. Trials. 2014;15:103. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson AGH, Suñol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. Int J Qual Health Care. 1995;7:127–141. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/7.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliver RL. Effect of expectation and disconfirmation on postexposure product evaluations:an alternative interpretation. J Appl Psychol. 1977;62:480–486. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliver RL. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J Mark Res. 1980;17:460–469. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sherif M, Taub D, Hovland CI. Assimilation and contrast effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments. J Exp Psychol. 1958;55:150–155. doi: 10.1037/h0048784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waljee J, McGlinn EP, Sears ED, Chung KC. Patient expectations and patient-reported outcomes in surgery: a systematic review. Surgery. 2014;155:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Turnbull AE, Davis WE, Needham DM, White DB, Eakin MN. Intensivist-reported facilitators and barriers to discussing post-discharge outcomes with intensive care unit surrogates: a qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1546–1552. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201603-212OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chipperfield JG, Hamm JM, Perry RP, Parker PC, Ruthig JC, Lang FR. A healthy dose of realism: the role of optimistic and pessimistic expectations when facing a downward spiral in health. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karnatovskaia LV, Schulte PJ, Philbrick KL, Johnson MM, Anderson BK, Gajic O, et al. Psychocognitive sequelae of critical illness and correlation with 3 months follow up. J Crit Care. 2019;52:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ketterer MW, Ouellette D, Jennings J. Psychoeducation for chronic cognitive impairment and reduced early readmissions amongst pulmonary inpatients. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24:1207–1212. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1601749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peale NV. The power of positive thinking. New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 1952.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.