Abstract

Background:

Our objective was to systematically review non-experimental studies of parental bipolar disorder (BD), current family environment, and offspring psychiatric disorders to identify characteristics of family environment associated with parental BD and risk for offspring psychiatric disorders.

Methods:

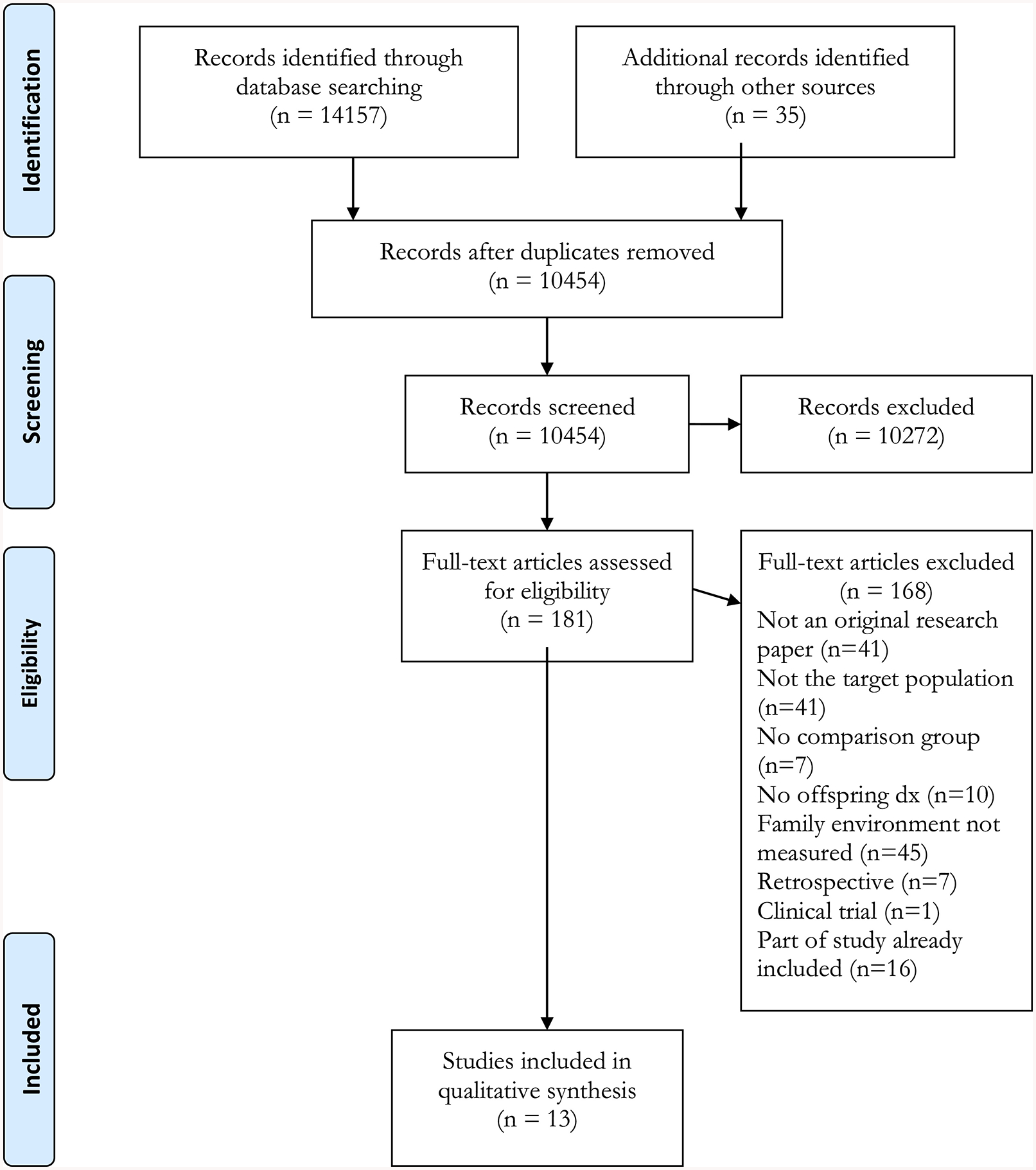

CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed were searched using MeSH terms to identify studies on offspring of BD parents published through September 2017. We followed PRISMA guidelines and used the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS). We calculated prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals to compare offspring psychiatric disorders within and across studies.

Results:

Of 10,454 unique documents retrieved, we included 13 studies. The most consistent finding was lower parent-reported cohesion in families with a BD parent versus no parental psychiatric disorders. Family environment did not differ between BD parents and parents with other disorders. Offspring of BD parents had higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders than offspring of parents without psychiatric disorders but did not differ from offspring of parents with other disorders. Families with a BD child had higher conflict than families without a BD child.

Limitations:

Comparisons between studies were qualitative. A single reviewer conducted screening, data extraction, and bias assessment.

Conclusions:

Family environment in families with a BD parent is heterogeneous. The pattern of findings across studies also suggests that family problems may be associated with parental psychiatric illness generally rather than parental BD in particular. Few studies included offspring-reported measures. Given the association of family conflict with offspring mood disorders, further study is merited on children’s perceptions of the family environment in the BD high-risk context.

Keywords: high-risk, bipolar disorder, family environment, parenting, family climate

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a persistent and impairing mood disorder associated with high public health burden (Crump, Sundquist, Winkleby, & Sundquist, 2013; Eaton et al., 2008; Goodwin & Jamison, 2007; Kessler, Merikangas, & Wang, 2007; Merikangas et al., 2011). Offspring of parents with BD have greater risk of developing BD and other psychiatric disorders than offspring of parents without psychiatric history (Delbello & Geller, 2001; Hodgins, Faucher, Zarac, & Ellenbogen, 2002; Rasic, Hajek, Alda, & Uher, 2014). Indeed, decades of genetics studies have shown that BD aggregates in families, and that much of the variance in risk for the disorder is due to genetics (Bearden, Zandi, and Freimer, 2016; Craddock & Sklar, 2013). However, BD is a complex disorder, the etiology of which is attributable to some combination of genes and environment (Alloy et al., 2005; Craddock & Sklar, 2013; Miklowitz & Chang, 2008; Post & Leverich, 2006; Rutten & Mill, 2009; Wray, Byrne, Stringer, & Mowry, 2014). The gap in understanding intergenerational transmission of BD and environmental impacts within the high-risk context limits opportunities for effective treatment or possible prevention. It is imperative to identify modifiable factors associated with increased risk for developing psychiatric disorders among offspring of BD parents, as well as factors associated with protection against developing psychiatric disorder in the BD high-risk context.

The family environment is a domain of particular interest in the BD high-risk context due to its great importance in child development and the hypothesis that environmental stressors related to parental BD increase risk aside from possible genetic transmission. Family environment is well established as having a central role in children’s physical, psychological, and socio-emotional development. Family theories tend to emphasize the parent-child relationship (Ainsworth, 1985; Bowlby, 1969; Bretherton, 1992), the interparental relationship (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Grych & Fincham, 1990), or the transactional nature of family interactions (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000; Schermerhorn & Cummings, 2008). In this study, we focus largely on parent-child relationships and the transactional nature of family dynamics, as opposed to the interparental relationship.

A key source of knowledge on BD has been studies of high-risk samples, which focus on subgroups at increased risk for a disorder due to one or more causes, such as family history. In these studies, comparisons are made between those with and without familial risk for a given disorder and between high-risk persons who develop a condition of interest and high-risk persons who remain free of the condition. Studying offspring of persons with BD may aid detection of etiologic factors (such as harsh family environment or gene-environment interaction); highlight timeframes most appropriate for interventions; and identify children who are experiencing distress or impairment (Chang, Steiner, Dienes, Adleman, & Ketter, 2003; Hodgins et al., 2002).

To increase understanding of malleable risk processes in the intergenerational transmission of BD, it would be useful to identify signature features of the family environment of BD parents and link those features to offspring outcomes, taking into account the quality of the literature. Oyserman and colleagues (2000) presented a thoughtful review of studies addressing mothering in the context of serious mental illness, but their review did not include fathers and did not review literature published after 1999. More recently, several groups of researchers (e.g., Alloy et al., 2006; Jones & Bentall, 2008; Miklowitz & Johnson, 2009; Reinares et al., 2016) have reviewed characteristics of family environment (e.g., expressed emotion, parenting) among persons with BD, but did not use systematic procedures for identifying and assessing relevant literature, uniformly present rates of high-risk offspring psychiatric diagnosis, or focus on current (rather than retrospective) reports. To our knowledge, there has been no systematic review that characterizes current family environment of families with a BD parent in contrast to families without a BD parent and compares rates of offspring psychiatric disorders between those two groups. Our objective was to systematically review non-experimental studies of parental BD, current family environment, and offspring psychiatric disorders in order to identify characteristics of family environment associated with parental BD and to compare risk for offspring psychiatric disorders in families with versus without parental BD.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We specified inclusion criteria relating to study participants, exposures (rather than interventions), comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS; Liberati et al., 2009). Although application of the PRISMA statement is more straightforward for a review of interventions, the guidelines may be modified to accommodate the different features of a review that addresses diagnoses (e.g., the spectrum of patients and verification of disease status are essential areas of concern) or disease etiology (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009). The participants were families parented by a BD-affected parent (probands may be parents with BD and/or offspring of parents with BD), with parent diagnostic group established based on clinical diagnostic interviews. The exposure was an assessment of family environment using behavioral observation procedures or established self-report questionnaires. While parents’ psychiatric disorder could be analyzed as an exposure, we assessed parent diagnostic group in the context of study samples and sampling. The comparators included at least one comparison group of families who were not parented by a BD-affected parent. For our outcome, we focused on psychiatric diagnoses in the offspring, requiring that diagnoses were assessed via clinical diagnostic interviews, to aid comparison across studies. The study design was non-experimental (i.e., observational) and could be prospective longitudinal or cross-sectional. Retrospective reports of family environment (e.g., adult offspring reporting on their childhood) were excluded due to potential for recall bias, in addition to the hope that identifying active family environments associated with parental BD and/or high-risk offspring diagnoses might inform preventive intervention efforts and future research.

Studies were included in the review if they met the aforementioned PICOS criteria and were original research papers published in a peer-reviewed journal. In cases of multiple papers from a larger longitudinal study or data source, a single study meeting all aforementioned inclusion criteria was selected. If more than one paper met all inclusion criteria, the paper reporting results with older offspring would be selected due to peak onset of BD beginning in late adolescence (Merikangas et al., 2011).

Search Strategy and Review Process

We developed our search strategy under the expert guidance of two information specialists. Four databases were searched for this review: CINAHL, Embase, PsycINFO, and PubMed. In PubMed, draft search strings using free-text and MeSH terms were tested and refined to maximize identification of articles about the target population of offspring of parents with BD. The other 3 databases (CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO) were searched with comparable terms, calibrating the search strings until they were conceptually equivalent. We did not limit our searches by outcome terms, with the goal to reduce risk of publication bias by capturing a wider range of full-text documents (Song, Hooper, & Loke, 2013). Appendix A lists the final search strings. We searched the references of the studies included in the review, as well as those in key background and related review articles, applying the aforementioned eligibility criteria. We checked the status of conference abstracts and dissertations/theses initially excluded during our criteria review, searching the literature and contacting authors as needed to identify subsequent papers in peer-reviewed journals (Song et al., 2013).

Metadata from the electronic searches were reviewed in RefWorks, and coding for each paper was saved in the RefWorks ‘User’ fields. Each paper was assessed using the criteria listed above, by first reading the title, and, as necessary, the abstract and full text of the paper. Inclusion in the analytic set was agreed on by consensus of all authors, with discussion of potential papers during the process of criteria review, and additional discussion during the process of extracting data. A protocol was not registered for this review. In order to compare prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the offspring across studies, we calculated prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals. We contacted authors of the primary studies as needed, to confirm or clarify information. Family environment was assessed through multiple methods, and, at times, non-overlapping measures, so a quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was not appropriate for family environment; nor did we include a funnel plot (Lau, Ioannidis, Terrin, Schmid, & Olkin, 2006). Instead, a qualitative synthesis of findings characterizing the BD high-risk family environment was developed, centered around key themes or domains of family environment (pointing out commonalities and inconsistencies as well as significantly different versus null findings, noting the type of comparison group), followed by presentation of offspring diagnoses and related family environments.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Based on recommendations for best practices in systematic reviews (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009), we assessed risk of bias within and across studies. We used the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies (RoBANS; Kim et al., 2013) to assess the risk of bias for each study included in this review. RoBANS includes assessments of six domains: selection of participants, confounding variables, exposure measurement, blinding of outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. Some domains (e.g., selective reporting) also speak to bias across studies. This process was completed by a single author (EKS).

Results

Of the 14,192 articles identified through database and manual searching, 10,454 remained after removing duplicates using a reference manager program. We excluded 10,272 documents in initial screening. After assessing 181 papers for eligibility in the second round of screening (see Figure 1 for PRISMA flow diagram), 13 papers published between 1987 and September 2017 were included in this review. Incidentally, all were published in the English language. Essential components (including PICOS characteristics) of the 13 papers in the analytic set are summarized in Table 1, including study sample, study design, age of offspring, diagnostic assessments of parents and offspring, measures used to assess family environment, family environment findings by parent diagnosis group, prevalence of offspring psychiatric diagnoses, and, if reported, associations between family environment and offspring diagnosis. Main findings are presented below, with RoBANS summaries in Table 2. Detailed summaries of individual studies and risk of bias are available from the first author upon request.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Key characteristics and findings of studies included in systematic review of BD high-risk family environment and offspring psychiatric disorders

| Author (Year) | Sample, by Parent Group N families (offspring) | Study Design | Age of Offspring range (mean) years | Parent Diagnosis | Family Environment Assessment | Family Environment Findings by Parent Diagnosis | Offspring Psychiatric Diagnosis, Prevalence by Parent Group | Family Environment Findings by Offspring Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burge & Hammen, 1991 | BD 12 (12) Unipolar 13 (13) Medical illness 11 (11) No psych 21 (21) | Longitudinal (6 mos) | 8–16 (male 12.75; female 12.42) | Parents: SADS-L; MMPI short form for no-dx group Offspring: K-SADS | Direct behavioral observation, coding adapted from PIRS | Maternal verbal behavior BD vs. Depressed: > task productive; < off-task, negative/disconfirming; n.s. positive/confirming (Gordon et al., 1989) Child-report: n/a | Depressive and nonaffective dx analyzed but prevalence not reported in Burge & Hammen, 1991. Full longitudinal sample (Hammen et al., 1990), any lifetime dx BD: 72% Unipolar: 82% Medical illness: 43% No psych: 32% | Offspring Depressive dx predicted from low positivity, n.s. task productivity. Offspring nonaffective dx n.s. related to maternal interaction characteristics. |

| Chang et al., 2001 | BD 36 (56) Normative sample of diverse families from US 1432 | Cross-sectional | 6–18 (10.4) | Parents: Semi-structured interview(DSM-IV criteria), and K-SADS-PLWASH-U-K-SADS and K-SADS-PL | FES | Parent-report BD compared to Normative: > CON, CTL, ICO; < AO, C, IND, ORG; n.s. ARO, EX, MRE Child-report: n/a | BD: 54% axis I; 14% BD I, II, or cyclothymia Normative: not measured | FES scores n.s. related to offspring dx (Axis I or BD) within-BD- parent group |

| Doucette et al., 2013 | BD (221) Control (no psych) (63) | Cross-sectional (from longitudinal study) | 7–20 at study entry Mean age for IPPA: BD offspring 21.6; Control 16.5 | Parents: SADS-L Offspring: K-SADS-L | IPPA | Child report BD compared to Control: n.s., IPPA-mother, n.s. IPPA-father Parent-report: n/a | BD: 41.2% mood disorder; 13.1% BD Control: 3.2% mood disorder; 1.6% BD | Among BD offspring: IPPA n.s. associated with offspring psychopathology (any dx); IPPA-mother score positively associated with offspring mood disorder. |

| Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008 | BD 76 (76) Unipolar 91 (91) Neither BD nor unipolar (no mood dx) 105 (105) | Cross-sectional | 5–17 (11.57) | Parents: SADS-LB (primary caregiver), SADS-LB, FH-RDC (other parent) Offspring: K-SADS-PL or KSADS-E | FAD and CBQ | Parent report FAD: BD compared to Unipolar: n.s. all subscales; BD compared to no mood dx. CBQ: n.s. across groups Child-report: n/a | BD in Offspring BD: 84% Unipolar: 54% No mood dx: 35% | Offspring with BD compared to no Axis I: > conflict (CBQ); n.s. family functioning (FAD total score, all subscales) |

| Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009 | BD 26 (28) No current psych hx, no lifetime mood dx 22 (26) | Longitudinal (8 yrs) | Time 1: 6–13 (9.1); Time 2: 13–21 (16.5) | Parents: SCID-I, medical records Offspring: DISC or SCID-I | PDI, when offspring were 6–13 yrs | Parent report BD compared to No psych hx: < Control (discipline strategies, maturity demands on children); n.s. Supportiveness (nurturance, responsiveness, non-restrictiveness), Structure (organization, consistency, involvement) Child-report: n/a | Any psych. dx (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009) BD: 17.9% Controls: 23.1% full longitudinal sample (Nijjar et al., 2014): BD: 65.7% any lifetime dx, 32.8% mood dx Controls: 41.2% any lifetime dx, 11.8% mood dx | Not reported by offspring diagnosis. |

| Ferreira et al., 2013 | BD 47 (47) Control (No Axis I) 30 (30) | Cross-sectional | 6–17 (BD 12, Control 13) | Parents: SCID-I Offspring: K-SADS-PL | FES (validated to Portugese) | Parent report BD compared to Control: > CON, CTL; < ARO, C, ICO, MRE, ORG; n.s. AO, EX, IND Child-report: n/a | BD: 47% axis I; 12.8% BD, 10.6% unipolar Control: 0% (selected during recruitment to be free of DSM-IV diagnoses) | BD families with affected compared to unaffected offspring and Control offspring: > CON, CTL; < ARO, C, ICO; n.s. AO, EX, IND; < MDE, ORG (affected BD offspring compared to Controls only). Within BD families, those with affected offspring compared to unaffected offspring: > CTL, n.s. all other subscales. |

| Goetz et al., 2017 | BD 34 (43) Controls (no Psychiatric disorders or treatment with psychotropic medication) 33 (43) | Cross-sectional | 6–17 (BD 12.5, Control 12.4; age-matched) | Parents: SADS-L; Interview by board-certified psychiatrist for Control parents Offspring: K-SADS-PL | KIDSCRE EN-52 | Parent report: n/a Child-report BD compared to Controls: < QoL in domain of parent relationship and home life, adjusted for current mood and anxiety symptoms and family status (intact parent relationship) | Lifetime disorders: BD: 86% any disorder; 32.5% any Mood disorder; 11.6% BD spectrum Control: 41.9% any; 2.3% mood; 0 BD | Not reported by offspring diagnosis. |

| Park et al., 2015 | BD 64 (64; 22 complete FACES data analyzed) Healthy controls (HC) 51 (51; 28 complete FACES data analyzed) | Cross-sectional | 9–18 (BD 13.73, HC 13.68) | Parents: SCID-I Offspring: WASH-U-K-SADS, K-SADS-PL | FACES-IV | Parent report BD compared to HC: < cohesion, family satisfaction, family communication; > enmeshment, chaos; n.s. rigidity, disengagement, balanced flexibility Child-report: n/a | BD (% of n=64): 55% BD-NOS, MDD, or Dysthymia HC: 0% (selected during recruitment to be free of DSM-IV diagnoses) | Not reported by offspring diagnosis. |

| Petti et al., 2004 | BD (23) Unaffected within-pedigree control group (27) | Cross-sectional | 6–17 (males 12.1, females 10.2) | Parents: DIGS Offspring: DICA-R | HEIC | Parent report and child report BD compared to Unaffected: n.s. closeness of siblings, financial difficulties, closeness to relatives outside the nuclear family, discipline. | BD: 39% mood disorder Unaffected: 11% mood disorder Mood disorders include bipolar I or II, major depressive episode, and dysthymia. | Parent-reported discipline higher in families with bipolar-affected versus unaffected offspring. |

| Romero et al. 2005 | BD 24 (24) ‘Healthy’ (No Axis I)27 (27) Normative 1432 | Cross-sectional | 8–12 (not reported) | Parents: SCID-P Offspring: WASH-U K-SADS | FES | Parent-report BD compared to Healthy: < C, EX; n.s. AO, ARO, CON. CTL, ICO, IND, MRE, ORG. BD compared to Normative: > CON, CTL, ICO, MRE; < C, IND; n.s. AO, ARO, EX, ORG. Child-report: n/a | BD: 71% mood disorder: 38% BD, 13% unipolar, 13% cyclothymia, 8% dysthymic disorder. Healthy: 3.7% (N=1) Mood disorder (dysthymia) | BD families with vs w/o offspring with BD: n.s. all FES subscales |

| Tarullo et al. 1994 | BD 22 (35) Unipolar 31 (58) ‘Well’ (No psych hx) 30 (54) | Cross-sectional (Time 3 from longitudenal study) | 82 preadolescent children 8–11 (9.28), 65 adolescent children 12–16 (13.43) | Parents: SCID at Time 3 (SADS-L at Time 1) Offspring: DICA-R | Direct behavioral observation, Coding of behavior factor analyzed | Preadolescents: Well mothers > engaged thanBD mothers. Maternal critical/irritable behavior n.s. Children of well and BD mothers > comfortable/happy than children of unipolar. Child engagement, critical/irritable n.s. Adolescents: Maternal engagement, critical/irritable n.s. Child engagement, critical/irritable, comfort/happiness n.s. | BD: 63% psychiatric disorder(s) in past year (59% preadolescents, 69% adolescents) Unipolar: 72% psychiatric disorder(s) in past year (71% preadolescents, 74% adolescents) Well: 46% psychiatric disorder(s) in past year (45% preadolescents, 48% adolescents) Normative: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders not available for sample | Preadolescents: Children with past-year problem: mothers > critical/irritable; children < engaged, > critical/irritable. Adolescents: BD mothers with children with No Problem < engaged than unipolar mothers of children with or without problems and well mothers of children with no problems. Children with No problems <Comfortable/happy with BD mothers than with unipolar or well mothers. |

| Vance et al., 2008 | BD 20 (23) ‘Control’ 20 (24) | Cross-sectional | 12–20 (not reported) | Parents: SCID-I Offspring: SADS-L | PACE and FRI | PACE: BD compared to Control: Parent report > negative consequences as result of hypothetical negative interpersonal events happening to their children; n.s.: child report FRI: BD compared to Control: Parent report: < expressiveness, n.s. cohesion, conflict; n.s.: child report | BD: 26% mood disorder ‘Control’: 4% mood disorder | Not reported by offspring diagnosis. |

| Weintra ub, 1987 | BD 58 (134) Schizophrenia 31 (80) Unipolar 70 (154) No psych hx 60 (176) | Longitudinal (~11 yrs) | Phase I: 7–15 (not reported); phase II follow-up 3 yrs later | Parents: CAPPS, hospital records, spouse’s ratings of patient’s psychiatric and social functioning Offspring: SADS or SCID | FEF, MAT, CRPBI, Environmental Q-Sort, and Minnesota-Briggs History Scale revised | Parent report BD compared to schizophrenia and unipolar depression: n.s. marital discord MAT), family function (FEF); Child report BD Comparison not reported on Environme ntal Q-Sort; CRPBI and MB-History Record results not explicitly presented. | BD: 20% any DSM-III dx (of that, 47.6% mood) Schizophrenia: 22.8% any DSM-III dx Unipolar 15.2% any DSM-III dx No psych hx: 9.6% any DSM-III dx DSM-III diagnoses include any schizophrenic, mood, personality, adjustmentanxiety, or substance use disorders. | Not reported by offspring diagnosis. |

Note: CAS=Child Assessment Schedule; CAPPS=Current and Past Psychopathology Scales; CRPBI=Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory; DIGS=Diagnostic Interview for Genetics Studies; DISC=Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children; DSM=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Dx=diagnosis; FACES-IV=Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales, version IV; FAD=Family Assessment Device; FEF=Family Evaluation Form; FES=Family Environment Scale (subscales: AO= achievement orientation; ARO=active-recreational orientation; C=cohesion; CON=conflict; CTL=control; EX=expressiveness; ICO=intellectual-cultural orientation; IND=independence; MRE=moral religious emphasis; ORG=organization); FH-RDC=Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria; FRI=Family relationships inventory; HEIC=Home Environment Interview for Children; IPPA=Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; K-SADS= Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; K-SADS-E=K-SADS-Epidemiological Version; K-SADS-PL=K-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version; WASH-U-K-SADS=Washington University in St Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorder and Schizophrenia; MAT=Marital Adjustment Test; MMPI=Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory n.s.=not significant; PACE=Parental Attributions for Children’s Events questionnaire; PDI=Parenting Dimension Inventory; PIRS=Peer Interaction Rating System; PPI=Parent Perception Inventory; QoL=Quality of Life; SADS=Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; SADS-L=SADS-Lifetime Version; SADS-LB=SADS-Lifetime Version, Bipolar; SCID=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III; SCID-I=Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCID-P=SCID-Patient Edition; US=United States

Table 2.

Assessment of risk of bias of studies included in systematic review of BD high-risk family environment and offspring psychiatric disorders

| Author, Year | Selection of Participants | Confounding Variables | Measurement of Exposure | Blinding of Outcome Assessments | Incomplete Outcome Data | Selective Outcome Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burge & Hammen, 1991 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Chang et al., 2001 | High | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Doucette et al., 2013 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009 | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Ferreira et al., 2013 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Goetz et al., 2017 | Unclear | low | High | Unclear | Low | Low |

| Park et al., 2015 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | High | Unclear |

| Petti et al., 2004 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Romero et al., 2005 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Low |

| Tarullo et al., 1994 | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Vance et al., 2008 | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Low | Unclear |

| Weintraub, 1987 | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

Note: Low, Unclear, and High connote the risk of bias in that particular domain. Risk of bias assessment conducted using the Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS).

Characteristics of Studies

Across 13 studies, there were 1859 total offspring, with sample sizes ranging from 47 to 544 offspring studied. Offspring ranged in age across studies from 5–21 years old. Most studies included offspring ranging in age from 6, 7, or 8 through 17 or 18 years. For studies reporting a mean age of offspring, it was typically between 10 and 13 and consistently younger than the mean age of onset of BD in the population.

Of the studies in which parent bipolar type was specified, 3 sampled parents with BD-I (Ferreira et al., 2013; Petti et al., 2004; Romero, DelBello, Soutullo, Stanford, & Strakowski, 2005) and 4 sampled parents with BD-I or -II (Chang, Blasey, Ketter, & Steiner, 2001; Doucette, Horrocks, Grof, Keown-Stoneman, & Duffy, 2013; Goetz et al., 2017; Park et al., 2015). The 6 remaining studies did not specify type of BD (Burge & Hammen, 1991; Du Rocher Schudlich, Youngstrom, Calabrese, & Findling, 2008; Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009; Tarullo, DeMulder, Martinez, & Radke-Yarrow, 1994; Vance, Jones, Espie, Tai, & Bentall, 2008; Weintraub, 1987). Several of these studies used DSM-III diagnostic criteria, which do not distinguish between BD-I and BD-II. Families under study were largely of White race and middle to middle-high socioeconomic status (SES). Comparison groups consisted of parents with depression, schizophrenia, chronic medical illness, or no psychiatric disorders; offspring of parents with the aforementioned diagnoses; or a normative U.S. sample from the 1970s recruited irrespective of psychiatric diagnosis. Comparison groups free of parental psychiatric disorders were most common.

Differences in Family Environment by Parent Diagnosis

The constructs used to operationalize ‘family environment’ range across theories and research studies, with different components of family dynamics assuming key roles. Findings focused on domains of family nurturance, communication, system maintenance, and, to a lesser extent, family values. While some studies presented both parent and child reports, most findings were based on parent-reported family environment. Individual study findings are presented in Table 1, with synthesis below.

Family nurturance.

In several studies, BD parents reported lower cohesion than parents without psychiatric disorders (“controls”) (Ferreira et al., 2013; Park et al. 2015; Romero et al., 2005) and in comparison with a historical U.S. normative sample (Chang et al., 2001, Romero et al., 2005). Relatedly, additional studies found that offspring of BD parents reported more problematic relationships with their parents and home life compared to controls (Goetz et al., 2017), and BD mothers had lower observed engagement than controls (‘well’ mothers) with preadolescent offspring (Tarullo et al., 1994). Despite consistency across five studies regarding lower cohesion in families with a BD parent, BD high-risk families did not differ significantly from controls on related constructs in several other studies, including observed engagement with adolescent offspring (Tarullo et al. 1994), disengagement (too low/unbalanced cohesion; Park et al., 2015), offspring-perceived attachment (Doucette et al. 2013), and parent-reported supportiveness (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009).

Family communication.

Findings from studies addressing communication and affect were mixed. Some parent reports suggested disrupted communication in BD high-risk families versus controls, with lower expressiveness (Romero et al., 2005, Vance et al., 2008) and communication (Park et al., 2015) and greater conflict (Ferreira et al. 2013) and negative inferential style (Vance et al. 2008) reported by parents. Greater conflict was reported in BD families compared to a U.S. normative sample (Chang et al. 2001, Romero et al. 2005). Other BD parents reported not significantly different levels of expressiveness (Ferreira et al., 2013, [compared to] controls; Chang et al., 2001 and Romero et al., 2005, U.S. normative sample), conflict (Romero et al. 2005 and Vance et al. 2008, controls; Du Rocher Schudlich et al. 2008, unipolar depressed; Weintraub 1987, depression or schizophrenia), and communication and problem solving (Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008, unipolar depressed). Observed maternal critical/irritable behaviors were not significantly different between mothers with BD and well or depressed mothers (Tarullo et al., 1994). The UCLA Family Stress project (Gordon et al., 1989) reported that BD mothers displayed less negative verbal behaviors and were more on-task than depressed mothers, but were not significantly different in positive/confirming statements.

Offspring of BD parents reported no differences on expressiveness and negative inferential style compared to offspring of parents without psychiatric disorders (Vance et al., 2008), and were not different in their own observed critical/irritable behavior compared to offspring of well or depressed mothers (Tarullo et al., 1994). Offspring of mothers with BD displayed more comfortable and happy interactions with their mothers than did the offspring of depressed mothers and were not significantly different from offspring of well mothers (Tarullo et al., 1994).

Family system maintenance.

Findings regarding components of system maintenance— such as organization, discipline, control, and flexibility—were mixed. Several studies found BD parents scored lower (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009, [compared to] controls) or higher on control (Ferreira et al., 2013, controls; Chang et al., 2001 and Romero et al. 2005, historical U.S. normative), lower on organization (Chang et al., 2001, historical U.S. normative; Ferreira et al., 2013, controls), and higher on chaos (Park et al., 2015, controls). Yet, other studies have reported no significant differences in BD-parented families on control and organization (Romero et al. 2005), rigidity (too low/unbalanced flexibility) and balanced flexibility (Park et al., 2015), and structure (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009) compared to controls; and on general family functioning compared to parents with depression (Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008; Weintraub, 1987) or schizophrenia (Weintraub, 1987).

Family values and personal growth.

The Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1994), captures family activities and preferences in addition to the domains above. Two studies found that families with BD parents versus controls did not differ on achievement orientation and independence (Ferreira et al., 2013; Romero et al. 2005). Romero and colleagues (2005) additionally found no significant differences on intellectual-cultural orientation, moral-religious emphasis, and active recreation orientation between BD parents and controls, whereas Ferreira and colleagues (2013) found BD parents scored lower than controls on all three of those components. Compared to a historical U.S. normative sample (Moos & Moos, 1994), both Chang and colleagues (2001) and Romero and colleagues (2005) found their contemporary BD families scored higher on intellectual-cultural orientation and lower on independence but did not differ significantly on active-recreational orientation. While the Chang et al. (2001) BD parents scored lower on achievement orientation, the Romero et al. (2005) BD parents were not significantly different from normative. And while the Romero et al. (2005) BD parents scored higher on moral-religious emphasis, the Chang et al. (2001) BD parents were not significantly different from normative.

Quantifying Offspring Psychiatric Diagnoses Across Studies

We calculated prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals for as many comparisons of offspring psychiatric disorders by parent diagnosis as available data allowed (Table 3). Comparisons were not possible for 3 of the 13 studies in which psychiatric disorders were only measured in the offspring of BD parents, not the comparison groups (Chang et al., 2001; Ferreira et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015). Offspring of parents with BD did not differ significantly from offspring of parents with unipolar depression, schizophrenia, or chronic medical illness in prevalence of any psychiatric disorder (Hammen et al., 1990; Tarullo et al., 1994; Weintraub, 1987). Offspring of parents with BD were diagnosed more frequently with psychiatric disorders than were offspring of parents without any psychiatric history, particularly when the offspring were older on average (Goetz et al., 2017; Hammen et al., 1990; Weintraub, 1987), but sometimes those differences were not significant (Tarullo et al., 1994; Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009). Mood disorders and especially BD were distinctly elevated among offspring of parents with BD compared to parents without BD (Petti et al., 2004; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008) and controls (Goetz et al., 2017; Doucette et al. 2013; Romero et al., 2005), although the differences were not always statistically significant (Vance et al., 2008).

Table 3.

Prevalence ratios of offspring psychiatric disorders by parent diagnostic group in systematic review of BD high-risk family environment and offspring psychiatric disorders

| Offspring Psychiatric Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Psychiatric Disorder Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) |

Mood Disorder Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | Bipolar Disorder Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | |

| 0.77 (0.27, 2.23); Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009 1.36 (0.92, 1.99); Tarullo et al., 1994 2.06 (1.42, 2.98); Goetz et al., 2017 2.08 (1.08, 4.03); Weintraub, 1987 2.29 (1.32, 3.96); Hammen et al., 1990a |

6.26 (0.82, 48.07); Vance et al., 2008 13.26 (3.36, 52.30); Doucette et al., 2013 14.00 (1.92, 101.83); Goetz et al., 2017 19.13 (2.75, 133.14); Romero et al., 2005 |

8.27 (1.15, 59.50); Doucette et al., 2013 | |

| BD versus No BD | 3.52 (1.08, 11.49); Petti et al., 2004 | 1.92 (1.59, 2.31); Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008 | |

| BD versus Unipolar Depression | 0.88 (0.62, 1.25); Hammen et al., 1990a 0.87 (0.64, 1.17); Tarullo et al., 1994 1.32 (0.76, 2.30); Weintraub, 1987 |

||

| BD versus Schizophrenia | 0.88 (0.50, 1.55); Weintraub. 1987 | ||

| BD versus Chronic Medical Illness | 1.69 (0.86, 3.29); Hammen et al., 1990a | ||

Notes: BD, Bipolar Disorder; CI, Confidence Interval. Prevalence ratios in boldare significant at p<0.05 (95% CIs do not include 1).

The prevalences from Hammen et al. 1990 were used for calculations in table based on larger N than Burge & Hammen, 1991; Burge & Hammen, 1991 did not present prevalence, although they did use the offspring disorders in analyses.

Differences in Family Environment by Offspring Psychiatric Diagnosis

Eight of the 13 studies tested for associations between offspring psychiatric diagnosis and family environment in addition to reporting differences on family environment between parent groups as described above; five did not assess these associations (Ellenbogen & Hodgins 2009; Goetz et al., 2017; Park et al., 2015; Vance et al., 2008; Weintraub, 1987). The most consistent finding, present in half of the 8 (Burge & Hammen, 1991; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008; Ferreira et al., 2013; Tarullo et al., 1994), was higher conflict or negativity in families with a child with BD (or mood disorder) irrespective of high-risk status.

In the three studies employing the Family Environment Scale (FES; Moos & Moos, 1994) to measure parent-reported family environment (Chang et al., 2001; Ferreira et al., 2013; Romero et al., 2005), the authors tested within BD families for differences in family environment based on whether the high-risk offspring were themselves diagnosed. Both Chang and colleagues (2001)—comparing any Axis I disorder versus none and BD versus no BD—and Romero and colleagues (2005)— comparing BD versus no BD—with mean offspring ages around 10 and 8–12 years respectively, reported no significant differences in FES scores by offspring diagnosis. On the other hand, Ferreira and colleagues (2013), studying offspring with a mean age of 12, found that within families with a parent with BD, those with offspring diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder scored higher on parent-reported control than families with offspring without psychiatric disorder. Families with BD parents and affected offspring, compared to BD families with unaffected offspring and control offspring, scored lower on cohesion, intellectual-cultural orientation, and active-recreational orientation, and higher on conflict and control subscales of the FES.

Another study found higher scores on parent-reported conflict in families in which offspring were diagnosed with BD compared to no Axis I disorders (using the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire [CBQ; Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979] rather than the FES; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008), but family functioning was not significantly associated with offspring BD diagnosis. Impaired family functioning—especially communication and problem solving—was predictive of conflict levels. After adjusting for conflict, impaired family functioning was more strongly associated with child diagnoses other than BD. Testing paths in both directions among parental mood, family functioning, conflict, and youth BD, the effect of youth BD on conflict was non-significant while the effect of conflict on youth BD remained large (Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008, p. 858). The study found that BD was nearly twice as prevalent among the offspring of parents with BD than without, highlighting the relevance of conflict (and its pathway from impaired communication and problem solving) on offspring BD diagnosis.

Parents but not offspring reported higher levels of discipline in the home in families in which offspring were affected with BD, regardless of whether the parent was affected (Petti et al., 2004). Among BD offspring, perceived attachment to either parent was not associated with diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder, although offspring perceptions of attachment with their mother were associated with offspring mood disorder—a finding the authors dismissed as spurious without explanation (Doucette et al. 2013).

Although prevalence of offspring psychiatric disorders was not significantly different across groups in the behavioral observation studies (see Table 3), significant associations of offspring disorders with family environment were reported. Burge and Hammen (1991) found that lower observed maternal positivity but not task productivity in mother-child communication and interactions predicted diagnoses of mood disorders, but not non-mood psychiatric disorders, in offspring. Tarullo and colleagues (1994) found that preadolescent offspring psychiatric disorders were positively associated with both maternal and child critical/irritable behavior and were inversely associated with engagement. Additionally, BD mothers were less engaged than well mothers with preadolescent and adolescent children with no past-year psychiatric disorder, who in turn were less comfortable/happy interacting with mothers with BD compared to unipolar depressed and well mothers (Tarullo et al., 1994).

Risk of Bias Across Studies

Table 2 provides a summary of our risk of bias assessment using the RoBANS tool, with common findings across studies below. Attempts to identify abstracts, dissertations, and unpublished outcomes in studies that otherwise met inclusion criteria yielded no additional papers. Six of the studies had notably low risk of bias (Burge & Hammen, 1991; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008; Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009; Petti et al., 2004; Romero et al., 2005; Tarullo et al., 1994), whereas risk of bias across 3 or 4 domains was unclear for the remaining studies. Adequate consideration of confounding and completeness of outcome reporting was present in most studies, whereas self-rated measurement of family environment exposure was rated higher risk and unclear presence or impact of blinding was common.

Selection bias.

The studies seldom reported participation rates or the characteristics of individuals who did not consent to participation. All studies used validated diagnostic interviews and trained interviewers, with varying levels of education (mostly post-graduate). Half of the studies we reviewed had a low risk of bias, in that the parent diagnoses were clearly measured with good diagnostic separation of groups, and we were reasonably certain that the groups came from comparable source populations. When the risk of bias was unclear (see Table 2), it was generally due to uncertainty as to whether cases and controls were drawn from the same source population. In one study (Hammen et al., 1987), different diagnostic measures were used for different study groups (SADS for psychiatric parental groups, MMPI for controls). The normative controls used by Chang and colleagues (2001) as the sole comparators were not from the same time period and geographic region as the BD parent group and were not assessed for psychiatric disorder, indicating potential for a high risk of bias.

Confounding.

The 13 studies reviewed herein were rated as having low risk of bias in this area, having presented consideration of sociodemographic characteristics in their modeling, with some studies presenting more thoughtful and complex models than others. However, parent comorbidities were rarely modeled.

Measurement of exposure.

Self-report measures have high risk of bias according to the RoBANS tool. Whether self-report measures of an exposure such as family environment should be considered to have a high risk of bias is debatable. Nonetheless, from this perspective, the majority of the studies in this review were assigned high risk of bias in measurement of exposure. Two studies have unclear risk of bias because they employed interviews (Petti et al., 2004; Weintraub, 1987), which still rely on the participant to report information where the interviewer may also influence reporting. Of the studies of direct observation of behavior of parents, one used a standardized procedure for evaluating the observation (Burge & Hammen, 1991); it was assigned low risk of bias. The other investigators developed their own structured coding system (Tarullo et al., 1994); the authors did not provide further information on the genesis of the system.

Blinding of outcome assessments.

The outcome measure was psychiatric diagnoses among offspring. Five studies demonstrated low risk of bias by either blinding raters to parent status (Burge & Hammen, 1991; Romero et al., 2005; Tarullo et al., 1994), completing diagnoses of the children first by treating the offspring as the probands (Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008), or blinding interviewers to study hypotheses and specific parental diagnoses even though, in the context of family genetics studies, the interviewers knew families came from BD pedigrees (Petti et al., 2004). Three studies had an unclear risk of bias because they did not mention blinding (Doucette et al., 2013; Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009; Weintraub, 1987). Three additional studies had an unclear risk of bias: although blinding to parent diagnostic status was not possible due to sampling decisions and study group composition, it was unclear whether lack of blinding affected prevalence of offspring diagnosis (Chang et al., 2001; Ferreira et al., 2013; Park et al., 2015). In 2 studies (Goetz et al., 2017; Vance et al., 2008), offspring diagnostic interviews were not blind to parent status, but it was unclear whether this approach was a source of bias.

Incomplete outcome data.

In 7 studies, the same number of participants were screened and analyzed (Chang et al., 2001; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008; Ferreira et al., 2013; Goetz et al., 2017; Petti et al., 2004; Romero et al., 2005; Vance et al., 2008). In another study, there was minimal loss to follow-up, which was equal across study groups (Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009), leading us to assign low risk of bias in these 8 studies. In contrast, one study had very high differences in missing data between groups, which may indicate high risk of bias (Park et al., 2015). The other studies were unclear, with differences between recruited and analyzed likely being due to age cut-offs (Doucette et al., 2013); refusers being not significantly different from consenters on sociodemographic characteristics, but “more severely disturbed and more paranoid” (Weintraub, 1987, p. 441); and, minimal loss to follow-up in the UCLA Family Stress project and the NIMH Childrearing Study but no discussion of whether there were significant between-group differences related to attrition (Burge & Hammen, 1991; Tarullo et al., 1994).

Selective outcome reporting.

The majority of the studies we reviewed had low risk of bias related to selective reporting, with findings reported for all key outcomes addressed in their objectives and methods (Chang et al., 2001; Doucette et al., 2013; Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008; Ellenbogen & Hodgins, 2009; Ferreira et al., 2013; Goetz et al., 2017; Petti et al., 2004; Romero et al., 2005; Tarullo et al., 1994). Although offspring disorders were diagnosed and analyzed in the family environment paper from the UCLA Family Stress Study reviewed here (Burge & Hammen, 1991), it was necessary to obtain prevalence of offspring diagnoses from another paper (Hammen et al., 1990). Three studies did not present all family environment scores, but, instead, only presented significant group differences (Park et al., 2015; Vance et al., 2008; Weintraub, 1987).

Discussion

We systematically reviewed the literature to identify non-experimental studies of parental BD, current family environment, and offspring psychiatric disorders. The 13 studies meeting inclusion criteria assessed various domains of family environment, including family nurturance, communication, system maintenance, and values. The most consistent finding across studies was lower parent-reported cohesion in families with a BD parent compared to families with no parental psychiatric disorders. Based on parent reports and observations, family environments did not consistently differ significantly between parents with BD versus parents with other major psychiatric or physical illnesses. Children’s perceptions of the family environment were rarely reported and did not tend to differ between groups. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders was higher among offspring of BD parents than offspring of parents without psychiatric disorders but not as compared to offspring of parents with other major disorders. Families in which a child was diagnosed with BD had higher conflict than families without a child with BD.

Importantly, children’s perceptions of their family environments were rarely obtained. Children may offer a different and vital perspective on family environment. It is possible that offspring diagnosis could be significantly related to children’s perceptions of family environment even when not related to parent-reported family environment. Children’s reports of the family environment, however, were not significantly different based on case/control status of the parents, which is reflected in some (Lau et al., 2018) but not all (Shalev et al., 2019) recent literature. Additionally, while some of the studies focused on the mother-child relationship, there were no studies focused on fathers only. Research from the Dutch Bipolar Offspring Study suggests there may be differences between BD mothers and BD fathers based on retrospective reports of the family environment by adult BD offspring (Kemner et al., 2015; Reichart et al., 2007).

Offspring Psychiatric Disorders and Associated Family Environment

Evidence was largely consistent across studies for elevated risk of developing psychiatric disorders—especially mood disorders—among offspring of parents with BD compared to offspring of parents with no psychiatric disorder. However, there was no evidence for elevated risk of psychiatric disorders when comparing offspring of BD parents to offspring of parents with another chronic psychiatric or physical illness. Two studies comparing families with versus without BD parents (comparison groups included both mood disorder-free parents and those with depression) had significantly higher prevalence of mood disorders in offspring; in these two studies, there was higher parent-reported discipline (Petti et al., 2004) and higher parent-reported conflict (Du Rocher Schudlich et al., 2008). A recent longitudinal study found higher rates of BD and non-BD axis I disorders, including depression, among offspring of BD parents compared to controls and offspring of parents with non-BD psychiatric disorders (Shalev et al., 2019). Importantly, while that study found offspring psychopathology mediated the effect of parent psychopathology on family environment, the direct effects of parent psychopathology on family environment were stronger.

Families in which offspring had a psychiatric disorder exhibited greater conflict than families in which the offspring did not have a psychiatric disorder. This is in line with studies on youth with BD (i.e., irrespective of parent status). The Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth study (Birmaher et al., 2014) found that parent-reported conflict was lower among BD youth who spent a greater proportion of time in euthymia, compared to a group of BD youth who were ill with an improving course. Additionally, scores on child-rated family cohesion and adaptability were highest in the trajectory class with the highest proportion of time spent in euthymia (Birmaher et al., 2014). Mother-child relationships have been reported to be higher in conflict and hostility, as well as lower in warmth, with BD youth compared to healthy controls and children with ADHD (Geller et al., 2000; Schenkel, West, Harral, Patel, & Pavuluri, 2008); low maternal warmth, in turn, is associated with shorter time to illness recurrence (Geller, Tillman, Craney, & Bolhofner, 2004). Relatedly, high levels of expressed emotion have been associated with relapse and social impairments in youth with BD (Miklowitz & Johnson, 2009). High parent-child conflict scores among adolescents with BD and their parents have also been associated with recent manic symptoms and emotional dysregulation (Timmins et al., 2016), as well as comorbid externalizing disorders (Esposito-Smythers et al., 2006).

It is possible that onset begins at earlier ages in high-risk samples than in the population (Baldessarini et al., 2011). The mean age of offspring in most of the studies was younger than the peak age of onset associated with BD and depression, yet the prevalence of mood disorders among high-risk offspring was already elevated. However, and importantly, most offspring of parents with BD do not develop the disorder. Therefore, aspects of the environment may protect against development of psychiatric disorder in those at risk due to family history. Alternatively, correlates of lower (or not significantly elevated) risk for psychiatric disorders may represent the absence of risk factors, rather than the presence of protective factors (Weintraub, 1987).

Related Family Contextual Factors

Divorce was not explicitly modeled in the studies included in this review, and in many of the earlier studies, a majority of parents were married. On a population level, community-dwelling US adults with BD are 80% more likely to be separated, divorced, or widowed than married or cohabitating (Grant et al., 2005). However, research suggests that the conflict leading to and surrounding divorce, rather than the change in family structure, is associated with negative outcomes for children (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Cummings & Davies, 2010). Additionally, adequate social support helps children adapt well following divorce (Hetherington, 1989).

Individuals with BD retrospectively report a higher prevalence of exposure to childhood maltreatment than individuals without BD (Alloy et al., 2006), and exposure to childhood maltreatment is associated with early onset and a more pernicious course of BD, onset and recurrence of mania, suicidality, and substance abuse disorders in patients with BD (Agnew-Blais & Danese, 2016; Daruy-Filho, Brietzke, Lafer, & Grassi-Oliveira, 2011; Doucette et al., 2016; Gilman et al., 2015; Sala, Goldstein, Wang, & Blanco, 2014). We excluded studies on abuse because they represent extreme negative caregiving behaviors, and we sought to capture the family environment more generally (e.g., climate) in the BD high-risk context. However, it is possible that some of the reviewed studies capture emotional abuse within their broader assessments of the family environment.

Limitations

Screening, criteria review, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were conducted by a single author (EKS), albeit with discussion and consensus among co-authors. Comparisons of family environment were qualitative due to the wide variety of measures spanning multiple domains. Limitations in the studies reviewed affect the nature of the conclusions that can be drawn about their findings. The possibility of selection bias is a concern in observational studies. When using convenience sampling, there is potential for differences between those who volunteer for studies and those who do not (Hernan, Hernandez-Diaz, & Robins, 2004), potentially affecting external validity of the study findings. There may be further differences when cases and controls are drawn from the clinic versus the community. Moreover, many study samples were predominantly White and middle to high SES. Additionally, use of a historical U.S. normative sample (Chang et al. 2001, Ferreira et al. 2013, Romero et al. 2005) as a comparison group is problematic; comparing groups from different time periods and populations introduces potential confounds (e.g., generational differences in parenting) that may limit capacity to detect meaningful differences between groups. Most studies relied on parent-report measures of family environment, but these reports may be influenced by parents’ characteristics, life experiences, and symptoms, in addition to the child’s behavior. Widely-used measures of family environment also have limitations; for instances, the FES is widely used but potential problems with reliability and validity have been noted (Boyd et al. 1997; Moos, 1990).

Directions for Future Research

Given the burden associated with BD, there is a pressing need to understand for whom, when, and how to intervene, informed by knowledge of cause and trajectory. Future research should seek offspring perceptions of their family environment. The field would be enriched by inquiry into the effect of paternal BD on the family environment, which has been understudied. An even more complete picture of the family environment in this context would be obtained by including the health of the co-parent, a mixture of both direct observations and self-report measures of the family environment, and comparisons to families with parents with other mental disorders and not simply diagnosis-free controls. Additionally, the majority of family environment measurement and analysis has been cross-sectional and does not capture the earliest years of life, or the possible effect of severity and timing of parent episodes on family environment over the course of offspring development. Gaps remain in understanding the potential differential effects of subtypes of BD on the family environment. Moreover, current parental functioning or symptoms may offer insight to understanding parent-child interactions and family climate above and beyond parental lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. Finally, it will be important to study the concomitant effects of biologic features in the BD high-risk context with elements of family environment and home life.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of BD high-risk studies assessing both the current family environment and offspring psychiatric disorders. Family environment in BD-parented families is heterogeneous, although parents with BD report lower family cohesion than parents without psychiatric disorders or normative controls. Recognizing the heterogeneity of individuals and family systems, it may be that it is less important to attempt to characterize all families with BD based on group means, than it is to identify subgroups of families with distinct challenges and needs. Finally, compared to parent-reports, there is a relative dearth of literature assessing children’s perceptions of the family environment in the BD high-risk context. Given the deleterious association noted between higher family conflict and offspring mood disorders, offspring-perceived family environment is a topic of public health importance that merits further consideration.

Highlights.

Family environment in BD-parented families is heterogeneous

BD parents report lower cohesion than controls but not other parents with disorders

Offspring perceptions of family environment in BD high-risk context are understudied

The association of BD fathers with family environment is understudied

Higher conflict was reported/observed when offspring had psychiatric disorders

Acknowledgements

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health [T32MH014592; PI: Peter P. Zandi] and in part by the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Role of the Funding Sources:

The funding sources had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Appendix A. Search Strings for September 2017 Dated Search, by Database

| Database | Search Strings |

|---|---|

| CINAHL | DE “Bipolar Disorder” or “bipolar disorder” or “bipolar” and “bipolar parents” or “parents with bipolar” or Predisposition or DE “Susceptibility (Disorders)” or DE “At Risk Populations” or offspring or DE “Biological Family” or DE “Predisposition” or DE “Offspring” or “high risk” or “at risk” or “at-risk” or “first-degree relative” or “biological family” |

| Embase | ‘genetic predisposition’/exp OR ‘genetic predisposition’ OR bipolar NEAR/3 parents OR ‘high risk population’/exp OR ‘high risk population’ OR ‘genetic risk’/exp OR ‘genetic risk’ OR ‘progeny’/exp OR progeny OR ‘progeny’/syn AND (‘bipolar disorder’/exp OR ‘bipolar’) |

| PsycINFO | DE “Bipolar Disorder” or “bipolar disorder” or “bipolar” and “bipolar parents” or “parents with bipolar” or Predisposition or DE “Susceptibility (Disorders)” or DE “At Risk Populations” or offspring or DE “Biological Family” or DE “Predisposition” or DE “Offspring” or “high risk” or “at risk” or “at-risk” or “first-degree relative” or “biological family” |

| PubMed | “Child of Impaired Parents”[Mesh] OR “Genetic Predisposition to Disease”[MeSH] OR “high risk offspring”[All Fields] OR “bipolar parents”[All Fields] OR “at risk”[All Fields] OR “at-risk”[All Fields] OR offspring[All Fields] OR “high risk”[All Fields] OR “high-risk”[All Fields] OR “familial risk”[All Fields] OR “first-degree relative”[All Fields] AND bipolar[All Fields] AND “bipolar disorder”[MeSH Terms] |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- Agnew-Blais J, & Danese A (2016). Childhood maltreatment and unfavourable clinical outcomes in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(4), 342–349. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00544-1. Epub 2016 Feb 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD (1985). Patterns of infant-mother attachments: antecedents and effects on development. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 61(9), 771–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Smith JM, Gibb BE, & Neeren AM (2006). Role of parenting and maltreatment histories in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders: Mediation by cognitive vulnerability to depression. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(1), 23–64. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0002-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Urosevic S, Walshaw PD, Nusslock R, & Neeren AM (2005). The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: Environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 1043–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Vazquez GH, Undurraga J, Bolzani L, Yildiz A, … Tohen M (2012). Age at onset versus family history and clinical outcomes in 1,665 international bipolar-I disorder patients. World Psychiatry, 11, 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden CE, Zandi PP, & Freimer NB (2016). Molecular architecture and neurobiology of bipolar disorder In Lehner T, Miller B, & State M (Eds.), Genomics, circuits, and pathways in clinical neuropsychiatry (pp. 467–486). London, Academic Press; 10.1016/B978-0-12-800105-9.00030-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Gill MK, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Goldstein TR, Yu H, … Keller MB (2014). Longitudinal trajectories and associated baseline predictors in youths with bipolar spectrum disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(9), 990–999. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1969). Attachment and loss, Volume 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1973). Attachment and loss, Volume 2: Separation. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CP, Gullone E, Needleman GL, & Burt T (1997). The Family Environment Scale: Reliability and normative data for an adolescent sample. Family Process, 36, 369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- *.Burge D, & Hammen C (1991). Maternal communication: Predictors of outcome at follow-up in a sample of children at high and low risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(2), 174–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KD, Steiner H, & Ketter TA (2000). Psychiatric phenomenology of child and adolescent bipolar offspring. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(4), 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Chang KD, Blasey C, Ketter TA, & Steiner H (2001). Family environment of children and adolescents with bipolar parents. Bipolar Disorders, 3(2), 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang K, Steiner H, Dienes K, Adleman N, & Ketter T (2003). Bipolar offspring: a window into bipolar disorder evolution. Biological Psychiatry, 53(11), 945–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, & Anda RF (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad M, & Hammen C (1993). Protective and resource factors in high-risk and low-risk children: A comparison of children with unipolar, bipolar, medically ill, and normal mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 5, 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N, & Sklar P (2013). Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet, 381(9878), 1654–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60855-7; 10.1016/S0140–6736(13)60855–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, & Sundquist J (2013). Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: A swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(9), 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, & Davies PT (2010). Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daruy-Filho L, Brietzke E, Lafer B, Grassi-Oliveira R (2011). Childhood maltreatment and clinical outcomes of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(6), 427–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, & Cummings EM (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, & Geller B (2001). Review of studies of child and adolescent offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disorders, 3(6), 325–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Doucette S, Horrocks J, Grof P, Keown-Stoneman C, & Duffy A (2013). Attachment and temperament profiles among the offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucette S, Levy A, Flowerdew G, Horrocks J, Grof P, Ellenbogen M, & Duffy A (2016). Early parent-child relationships and risk of mood disorder in a Canadian sample of offspring of a parent with bipolar disorder: Findings from a 16-year prospective cohort study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 10(5), 381–389. doi: 10.1111/eip.12195. Epub 2014 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Du Rocher Schudlich TD, Youngstrom EA, Calabrese JR, & Findling RL (2008). The role of family functioning in bipolar disorder in families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(6), 849–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Martins SS, Nestadt G, Bienvenu OJ, Clarke D, & Alexandre P (2008). The burden of mental disorders. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30, 1–14. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen MA, & Hodgins S (2004). The impact of high neuroticism in parents on children’s psychosocial functioning in a population at high risk for major affective disorder: A family– environmental pathway of intergenerational risk. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 113–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ellenbogen MA, & Hodgins S (2009). Structure provided by parents in middle childhood predicts cortisol reactivity in adolescence among the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(5), 773–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE (1982). Interparental conflict and the children of discord and divorce. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 310–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito-Smythers C, Birmaher B, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Hunt J, Ryan N, … & Keller M (2006). Child comorbidity, maternal mood disorder, and perceptions of family functioning among bipolar youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(8), 955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … & Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Ferreira GS, Moreira CRL, Kleinman A, Nader ECGP, Gomes BC, Teixeira AMA, … Caetano SC (2013). Dysfunctional family environment in affected versus unaffected offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 47(11), 1051–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Williams M, DelBello MP, & Gunderson K (2000). Psychosocial functioning in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1543–1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Ni MY, Dunn EC, Breslau J, McLaughlin KA, Smoller JW, & Perlis RH (2015). Contributions of the social environment to first-onset and recurrent mania. Molecular Psychiatry, 20, 329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Goetz M, Sebela A, Mohaplova M, Ceresnakova S, Ptacek R, & Novak T (2017). Psychiatric disorders and quality of life in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 27(6), 483–493. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0056. Epub 2017 Jun 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin F, & Jamison K (2007). Manic-depressive illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Burge D, Hammen C, Adrian C, Jaenicke C, & Hiroto D (1989). Observations of interactions of depressed women with their children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(1), 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, & Huang B (2005). Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(10), 1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, & Armsden G (2009). Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment Manual. http://www.prevention.psu.edu/media/prc/files/IPPAManualDecember2013.pdf Accessed April 20, 2014.

- Grych JH, & Fincham FD (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 267–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Burge D, Burney E, & Adrian C (1990). Longitudinal study of diagnoses in children of women with unipolar and bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47(12), 1112–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Adrian C, Gordon D, Burge D, Jaenicke C, & Hiroto D (1987). Children of depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptom predictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(3), 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernan MA, Hernandez-Dıaz S, & Robins JM (2004). A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology, 15, 615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM (1989). Coping with family transitions: Winners, losers, and survivors. Child Development, 60, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins S, Faucher B, Zarac A, & Ellenbogen M (2002). Children of parents with bipolar disorder: A population at high risk for major affective disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 11(3), 533–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, & Moos RH (1983). The quality of social support: Measures of family and work relationships. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 22, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SB, Riley AW, Granger DA, & Riis J (2013). The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics, 131(2), 319–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SH, & Bentall RP (2008). A review of potential cognitive and environmental risk markers in children of bipolar parents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008, 28(7), 1083–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR, & Wang PS (2007). Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the united states at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 137–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Park JE, Lee YJ, Seo HJ, Sheen SS, Hahn S, … Son HJ (2013). Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(4), 408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouneski EF (2000). The family circumplex model, FACES II, and FACES III: Overview of research and applications. St. Paul: University of Minnesota; http://www.facesiv.com. Accessed March 25, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, & Olkin I (2006). The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ, 333, 597–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau P, Hawes DJ, Hunt C, Frankland A, Roberts G, Wright A, … & Mitchell PB (2018) Family environment and psychopathology in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, … Moher D (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339, b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, … Swendsen J (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Jin R, He JP, Kessler RC, Lee S, Sampson NA, … Zarkov Z (2011). Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(3), 241–251. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, & Chang KD (2008). Prevention of bipolar disorder in at-risk children: Theoretical assumptions and empirical foundations. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 881–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DL, & Johnson SL (2009). Social and familial factors in the course of bipolar disorder: Basic processes and relevant interventions. Clinical Psychology, 16(2), 281–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01166.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH (1990). Conceptual and empirical approaches to developing family-based assessment procedures: resolving the case of the Family Environment Scale. Family Process, 29(2), 199–208; discussion 209–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, & Moos BS (1994). Family Environment Scale Manual, Third Edition Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nijjar R, Ellenbogen MA, & Hodgins S (2014). Personality, coping, risky behavior, and mental disorders in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: A comprehensive psychosocial assessment. Journal of Affective Disorders, 166, 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Bell RQ, & Portner J (1982). FACES II: Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales. Available from Life Innovations, Inc., P. O. Box 190, Minneapolis, MN 55440. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Mowbray CT, Meares PA, & Firminger KB (2000). Parenting among mothers with a serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(3), 296–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Park MH, Chang KD, Hallmayer J, Howe ME, Kim E, Hong SC, & Singh MK (2015). Preliminary study of anxiety symptoms, family dysfunction, and the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met genotype in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 61, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.11.013 Epub 2014 Nov 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Petti T, Reich W, Todd RD, Joshi P, Galvin M, Reich T, … Nurnberger J Jr. (2004). Psychosocial variables in children and teens of extended families identified through bipolar affective disorder probands. Bipolar Disorders, 6(2), 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, & Leverich GS (2006). The role of psychosocial stress in the onset and progression of bipolar disorder and its comorbidities: The need for earlier and alternative modes of therapeutic intervention. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 1181–1211. doi: 10.10170S0954579406060573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]